Iranian architecture

Iranian architecture or Persian architecture (Persian: معمارى ایرانی, Me'māri e Irāni) is the architecture of Iran and parts of the rest of West Asia, the Caucasus and Central Asia. Its history dates back to at least 5,000 BC with characteristic examples distributed over a vast area from Turkey and Iraq to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and from the Caucasus to Zanzibar. Persian buildings vary greatly in scale and function, from vernacular architecture to monumental complexes.[2] In addition to historic gates, palaces, and mosques, the rapid growth of cities such as the capital Tehran has brought about a wave of demolition and new construction.

According to American historian and archaeologist Arthur Pope, the supreme Iranian art, in the proper meaning of the word, has always been its architecture. The supremacy of architecture applies to both pre- and post-Islamic periods.[3] Iranian architecture displays great variety, both structural and aesthetic, from a variety of traditions and experience. Without sudden innovations, and despite the repeated trauma of invasions and cultural shocks, it developed a recognizable style distinct from other regions of the Muslim world.[4] Its virtues are "a marked feeling for form and scale; structural inventiveness, especially in vault and dome construction; a genius for decoration with a freedom and success not rivaled in any other architecture".[5]

General characteristics

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2023) |

Fundamental principles

[edit]

Traditional Persian architecture has maintained a continuity that, although temporarily distracted by internal political conflicts or foreign invasion, nonetheless has achieved an unmistakable style.[4]

Arthur Pope, a 20th-century scholar of Persian architecture, described it in these terms: "there are no trivial buildings; even garden pavilions have nobility and dignity, and the humblest caravanserais generally have charm. In expressiveness and communicativity, most Persian buildings are lucid, even eloquent. The combination of intensity and simplicity of form provides immediacy, while ornament and, often, subtle proportions reward sustained observation."[6]

According to scholars Nader Ardalan and Laleh Bakhtiar, the guiding formative motif of Iranian architecture has been its cosmic symbolism "by which man is brought into communication and participation with the powers of heaven".[7][page needed] This theme has not only given unity and continuity to the architecture of Persia, but has been a primary source of its emotional character as well.[clarification needed]

Materials

[edit]

Available building materials dictate major forms in traditional Iranian architecture. Heavy clays, readily available at various places throughout the plateau, have encouraged the development of the most primitive of all building techniques, molded mud, compressed as solidly as possible, and allowed to dry. This technique, used in Iran from ancient times, has never been completely abandoned. The abundance of heavy plastic earth, in conjunction with a tenacious lime mortar, also facilitated the development and use of brick.[8]

Design

[edit]

Certain design elements of Persian architecture have persisted throughout the history of Iran. The most striking are a marked feeling for scale and a discerning use of simple and massive forms. The consistency of decorative preferences, the high-arched portal set within a recess, columns with bracket capitals, and recurrent types of plan and elevation can also be mentioned. Through the ages these elements have recurred in completely different types of buildings, constructed for various programs and under the patronage of a long succession of rulers.

The columned porch, or talar, seen in the rock-cut tombs near Persepolis, reappear in Sassanid temples, and in late Islamic times it was used as the portico of a palace or mosque, and adapted even to the architecture of roadside tea-houses. Similarly, the dome on four arches, so characteristic of Sassanid times, is a still to be found in many cemeteries and Imamzadehs across Iran today. The notion of earthly towers reaching up toward the sky to mingle with the divine towers of heaven lasted into the 19th century, while the interior court and pool, the angled entrance and extensive decoration are ancient, but still common, features of Iranian architecture.[6]

City planning

[edit]A circular city plan was a characteristic of several major Parthian and Sasanian cities, such as Hatra and Gor (Firuzabad). Another city design was based on a square geometry, found in the Eastern Iranian cities such as Bam and Zaranj.[10]

Categorization of styles

[edit]

Overall, Mohammad Karim Pirnia categorizes the traditional architecture of the Iranian lands throughout the ages into the six following classes or styles ("sabk"):[11]

- Zoroastrian:

- The Parsian style (up until the third century BCE) including:

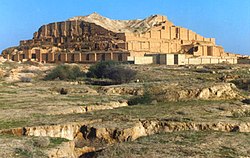

- Pre-Parsian style (up until the eighth century BCE) e.g. Chogha Zanbil,

- Median style (from the eighth to the sixth century BCE),

- Achaemenid style (from the sixth to the fourth century BCE) manifesting in construction of spectacular cities used for governance and inhabitation (such as Persepolis, Susa, Ecbatana), temples made for worship and social gatherings (such as Zoroastrian temples), and mausoleums erected in honor of fallen kings (such as the Tomb of Cyrus the Great),

- The Parthian style includes designs from the following eras:

- Seleucid era e.g. Anahita Temple, Khorheh,

- Parthian era e.g. Hatra, the royal compounds at Nysa,

- Sassanid era e.g. Ghal'eh Dokhtar, the Taq-i Kisra, Bishapur, Darband (Derbent).

- The Parsian style (up until the third century BCE) including:

- Islamic:

- The Khorasani style (from the late 7th until the end of the 10th century CE), e.g. Jameh Mosque of Nain and Jameh Mosque of Isfahan,

- The Razi style (from the 11th century to the Mongol invasion period) which includes the methods and devices of the following periods:

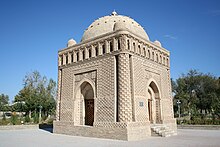

- Samanid period, e.g. Samanid Mausoleum,

- Ziyarid period, e.g. Gonbad-e Qabus,

- Seljukid period, e.g. Kharraqan towers,

- The Azari style (from the late 13th century to the appearance of the Safavid dynasty in the 16th century), e.g. Soltaniyeh, Arg-i Alishah, Jameh Mosque of Varamin, Goharshad Mosque, Bibi Khanum mosque in Samarqand, tomb of Abdas-Samad, Gur-e Amir, Jameh mosque of Yazd

- The Isfahani style spanning through the Safavid, Afsharid, Zand, and Qajarid dynasties starting from the 16th century onward, e.g. Chehelsotoon, Ali Qapu, Agha Bozorg Mosque, Kashan, Shah Mosque, Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque in Naqsh-i Jahan Square.

Pre-Islamic architecture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2023) |

-

Hatra in Nineveh, Iraq. From the 3rd to 1st century BCE, although no archeological information on the city before the Parthian period but settlement in the area likely dates back to at least the Seleucid period.[12] Hatra was a religious and trading center. Today it is a World Heritage Site, protected by UNESCO.[13]

-

Sassanid Rayen Castle

The pre-Islamic styles draw on 3000 to 4000 years of architectural development from various civilizations of the Iranian plateau. The post-Islamic architecture of Iran in turn, draws ideas from its pre-Islamic predecessor, and has geometrical and repetitive forms, as well as surfaces that are richly decorated with glazed tiles, carved stucco, patterned brickwork, floral motifs, and calligraphy.

Iran is recognized by UNESCO as being one of the cradles of civilization.[14]

Each of the periods of Elamites, Achaemenids, Parthians and Sassanids were creators of great architecture that, over the ages, spread far and wide far to other cultures. Although Iran has suffered its share of destruction, including Alexander The Great's decision to burn Persepolis, there are sufficient remains to form a picture of its classical architecture.

The Achaemenids built on a grand scale. The artists and materials they used were brought in from practically all territories of what was then the largest state in the world. Pasargadae set the standard: its city was laid out in an extensive park with bridges, gardens, colonnaded palaces and open column pavilions. Pasargadae along with Susa and Persepolis expressed the authority of 'The King of Kings', the staircases of the latter recording in relief sculpture the vast extent of the imperial frontier.

With the emergence of the Parthians and Sassanids new forms appeared. Parthian innovations fully flowered during the Sassanid period with massive barrel-vaulted chambers, solid masonry domes and tall columns. This influence was to remain for years to come.

For example, the roundness of the city of Baghdad in the Abbasid era, points to its Persian precedents, such as Firouzabad in Fars.[15] Al-Mansur hired two designers to plan the city's design: Naubakht, a former Persian Zoroastrian who also determined that the date of the foundation of the city should be astrologically significant, and Mashallah ibn Athari, a former Jew from Khorasan.[16]

The ruins of Persepolis, Ctesiphon, Sialk, Pasargadae, Firouzabad, and Arg-é Bam give us a distant glimpse of what contributions Persians made to the art of building. The imposing Sassanid castle built at Derbent, Dagestan (now a part of Russia) is one of the most extant and living examples of splendid Sassanid Iranian architecture. Since 2003, the Sassanid castle has been listed on Russia's UNESCO World Heritage list.

Sub-periods

[edit]According to Mohammad Karim Pirnia, the ancient architecture of Iran can be divided into the following periods.

Pre-Parsian style

[edit]The pre-Parsian style (New Persian:شیوه معماری پیش از پارسی) is a sub-style of architecture (or "zeer-sabk") when categorizing the history of Persian/Iranian architectural development. This architectural style flourished in the Iranian Plateau until the eighth century BC, during the era of the Median Empire. It is often classified as a subcategory of Parsian architecture.[17] The oldest remains of the architectural landmarks in this style are the Teppe Zagheh, near Qazvin. Other extant examples of this style are Chogha Zanbil, Sialk, Shahr-i Sokhta, and Ecbatana. Elamite and proto-Elamite buildings among others, are covered within this stylistic subcategory as well.

-

Sialk necropolis. 3000–4000 BC

-

Chogha Zanbil ziggurat. 1250 BC

Parsian style

[edit]The "Persian style" (New Persian:شیوه معماری پارسی) is a style of architecture ("sabk") defined by Mohammad Karim Pirnia when categorizing the history of Persian/Iranian architectural development. Although the Median and Achaemenid architecture fall under this classification, the pre-Achaemenid architecture is also studied as a sub-class of this category.[17] This style of architecture flourished from eighth century BCE from the time of the Median Empire, through the Achaemenid empire, to the arrival of Alexander the Great in the third century BCE[18]

-

Persepolis

-

Pasargad

-

Naqsh-e Rostam

Parthian style

[edit]This architectural style includes designs from the Seleucid (310–140 BCE), Parthian (247 BCE – 224 CE), and Sassanid (224–651 CE) eras, reaching its apex of development in the Sassanid period. Examples of this style are Ghal'eh Dokhtar, the royal compounds at Nysa, Anahita Temple, Khorheh, Hatra, the Ctesiphon vault of Kasra, Bishapur, and the Palace of Ardashir in Ardeshir Khwarreh (Firouzabad).[19]

Islamic architecture

[edit]

Early Islamic period (7th–9th centuries)

[edit]The Islamic era began with the formation of Islam under the leadership of Muhammad in early 7th-century Arabia. The Arab-Muslim conquest of Persia began soon afterwards and ended with the region coming under the control of the Rashidun Caliphs, followed by the Umayyad Caliphs after 661. Early Islamic architecture was heavily influenced by Byzantine architecture and Sasanian architecture. Umayyad architecture (661–750) drew on elements of these traditions, mixing them together and adapting them to the requirements of the new Muslim patrons.[20][21]

After the overthrow of the Umayyads in 750 and their replacement by the Abbasid Caliphate, the caliphate's political center shifted further east to the new capital of Baghdad, in present-day Iraq. Partly as a result of this, Abbasid architecture was even more influenced by Sasanian architecture and by its roots in ancient Mesopotamia.[22][23] During the 8th and 9th centuries, the power and unity of the Abbasid Caliphate allowed architectural features and innovations from its heartlands to spread quickly to other areas of the Islamic world under its influence, including Iran.[24]

Features from the Umayyad period, such as vaulting, carved stucco, and painted wall decoration, were continued and elaborated in the Abbasid period.[23] The four-centred arch, a more sophisticated form of the pointed arch, is first attested during the 9th century in Abbasid monuments at Samarra in Iraq, such as the Qasr al-Ashiq palace.[25][23] It became widely used in later Iranian architecture.[26] Samarra also saw the appearance of new decorative styles, which rendered the earlier vegetal motifs of Sasanian and Byzantine traditions into more abstract and stylized forms, as exemplified by the so-called "beveled" style. This style subsequently spread to other regions, including Iran.[27]

Few of the major mosques built during this early Islamic period in Iran have survived in something close to their original form. Remains of a mosque at Susa, probably from the Abbasid period, show that it had a hypostyle prayer hall (i.e. a hall with many columns supporting a roof) and a courtyard.[23] Another mosque excavated at Siraf dates to the 9th century.[28] Attached to the mosque was a minaret (tower for the muezzin to issue the call to prayer), the base of which remains, constituting the oldest remnants of a minaret in the eastern Islamic world.[29] The Jameh Mosque of Isfahan, one of the major Islamic monuments in Iran, was originally founded towards 771, but it was rebuilt and expanded in 840–841. It too had a courtyard surrounded by hypostyle halls. It continued to undergo further modifications and additions in subsequent centuries.[30]

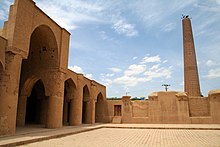

The only major mosque from this early period to preserve some of its original form is the Tarikhaneh Mosque in Damghan. Though the chronology of its construction is not well-documented, its overall form and style may date to the 9th century,[28] or possibly earlier, given its close similarities with Sassanid architecture.[23][31] It has a courtyard surrounded by a portico and a hypostyle prayer hall where the central aisle leading to the mihrab (a niche in the wall symbolizing the qibla) is slightly wider than the other aisles. It originally had no minaret, but a tall cylindrical tower was added to it in 1026.[28] This minaret is now the oldest one still standing in Iran.[32]

In secular architecture, the remains of various palaces and residences from this period have also been studied, such as those around Merv (present-day Turkmenistan). They shared many features with earlier Sasanian and Sogdian architecture.[23] Among the recurring elements are iwans and domed chambers. Some of the earlier examples up to the 8th century seem to have had halls with wooden pillars and roofs, while those that probably date to the 9th century seem to have favored domes and vaulted ceilings. They also had stucco decoration executed in the styles of Samarra.[23] Residences built in the countryside were enclosed by outer walls with semi-circular towers, while on the inside they had central courtyards or a central domed hall flanked by vaulted halls. Some had four iwans flanking a central courtyard.[23] The Sasanian tradition of building caravanserais along trade routes also continued, with the remains of one such structure in southern Turkmenistan attesting to the presence of a central courtyard surrounded by arcaded galleries with domed roofs.[23]

Emergence of regional style (10th–11th centuries)

[edit]

After its initial apogee of power, the Abbasid Caliphate fragmented into regional states in the 9th and 10th centuries that were formally obedient to the caliphs in Baghdad but were de facto independent.[34] In Iran and Central Asia, a number of local and regional dynasties rose to power by the 10th century: Iraq and central Iran were controlled by the Buyid dynasty, northern Iran was ruled by the Bawandids and Ziyarids, and the northeastern regions of Khurasan and Transoxiana were ruled by the Samanids, with other dynasties arising in Central Asia soon after.[35]

It is around this period that many of the distinctive features of subsequent Iranian and Central Asian architecture first emerged, including the use of baked brick for both construction and decoration, the use of glazed tile for surface decoration, and the development of muqarnas (three-dimensional geometric vaulting) from squinches. Hypostyle mosques continued to be built and there is also evidence of multi-domed mosques, though most mosques were modified or rebuilt in later eras.[35] The Jameh Mosque of Na'in, one of the oldest surviving congregational mosques in Iran, contains some of the best-preserved features from this period, including decorative brickwork, Kufic inscriptions, and rich stucco decoration featuring vine scrolls and acanthus leaves that draw from the earlier styles of Samarra.[35][33]

Another important architectural trend to arise in the 10th to 11th centuries is the development of mausolea, which took on monumental forms for the first time. One type of mausoleum was the tomb tower, such as the Gunbad-i-Qabus (circa 1006–7), while the other main type was the domed square, such as the Tomb of the Samanids in Bukhara (before 943).[38][35]

Seljuk era (11th–13th centuries)

[edit]Turkic peoples began moving west across Central Asia and towards the Middle East from the 8th century onward, eventually converting to Islam and becoming major forces in the region. The most significant of these were the Seljuk Turks, who formed the Great Seljuk Empire in the 11th century, conquering all of Iran and other extensive territories in Central Asia and the Middle East.[39]

While the apogee of the Great Seljuks was short-lived, it represents a major benchmark in the history of Islamic art and architecture in Iran and Central Asia, inaugurating an expansion of patronage and of artistic forms.[41][42] Much of the Seljuk architectural heritage was destroyed during the Mongol invasions in the 13th century.[43] Nonetheless, compared to pre-Seljuk Iran, a larger volume of surviving monuments and artifacts from the Seljuk period has allowed scholars to study the arts of this era in greater depth.[41][42] Several neighbouring dynasties and empires contemporary with the Seljuks, including the Qarakhanids, the Ghaznavids, and the Ghurids, built monuments in a very similar style. A general tradition of architecture was thus shared across most of the eastern Islamic world (Iran, Central Asia, and parts of the northern Indian subcontinent) throughout the Seljuk period and its decline, from the 11th to 13th centuries.[41][42] This period is also regarded as a "classical" age of Central Asian architecture.[44]

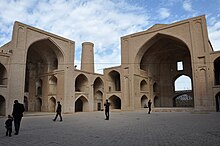

The most important religious monument from the Great Seljuk period is the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan, which was expanded and modified by various Seljuk patrons in the late 11th century and early 12th century. Two major and innovative domed chambers were added to it in the late 11th century. Four large iwans were then erected around the courtyard around the early 12th century, giving rise to the four-iwan plan in mosque architecture.[40][45][46] The four-iwan plan quickly became popular and was applied to other major mosques around this time, including those of Ardestan and Zavareh, as well as in secular architecture.[35] It was probably also used for madrasas, a new type of building introduced around this time, though none of the Seljuk madrasas have been well preserved.[35]

Lodging places (khān, or caravanserai) for travellers and their animals, generally displayed utilitarian rather than ornamental architecture, with rubble masonry, strong fortifications, and minimal comfort.[47] Large caravanserais were built as a way to foster trade and assert Seljuk authority in the countryside. They typically consisted of a building with a fortified exterior appearance, monumental entrance portal, and interior courtyard surrounded by various halls, including iwans. Some notable examples, only partly preserved, are the caravanserais of Ribat-i Malik (c. 1068–1080) and Ribat-i Sharaf (12th century) in Transoxiana and Khorasan, respectively.[48][35][49]

The Seljuks also continued to build "tower tombs", an Iranian building type from earlier periods, such as the Toghrul Tower built in Rayy (south of present-day Tehran) in 1139. More innovative, however, was the introduction of mausoleums with a square or polygonal floor plan, which later became a common form of monumental tombs. Early examples of this are the two Kharraqan Mausoleums (1068 and 1093) near Qazvin (northern Iran), which have octagonal forms, and the large Mausoleum of Sanjar (c. 1152) in Merv (present-day Turkmenistan), which has a square base.[50]

Around the same time, between the late 10th century and the early 13th century, the Turkic Qarakhanids ruled in Transoxiana and executed many impressive constructions in Bukhara and Samarkand (present-day Uzbekistan). Among the known Qarakhanid monuments are the great congregational mosque in Bukhara, of which only the Kalyan Minaret (c. 1127) survives, the nearby Minaret of Vabkent (1141), and several Qarakhanid mausoleums with monumental façades, such as those in Uzgen (present-day Kyrgyzstan) from the second half of the 12th century.[44]

Further east, the first major Turkic dynasty was the Ghaznavids, who became independent in the late 10th century and ruled from Ghazna, in present-day Afghanistan. In the second half of the 12th century, the Ghurids replaced them as the major power in the region from northern India to the edge of the Caspian Sea.[51][52] Among the most remarkable monuments of these two dynasties are a number of ornate brick towers and minarets which have survived as stand-alone structures. Their exact functions are unclear. They include the Tower of Mas'ud III near Ghazna (early 12th century) and the Minaret of Jam built by the Ghurids (late 12th century), also in present-day Afghanistan.[53][54]

As the Great Seljuks declined in the 12th century, various other dynasties (often also of Turkic origin) formed smaller states and empires. In Iran and Central Asia, the Khwarazm-Shahs, formerly vassals of the Seljuks and Qara Khitai, took advantage of this to expand their power and form the Khwarazmian Empire, occupying much of the region and conquering the Ghurids in the early 13th century, only to fall soon after to the Mongol invasions.[52] The site of the former Khwarazmian capital, Kunya-Urgench (in present-day Turkmenistan), has preserved several monuments from the Khwarazmian Empire period (late 12th and early 13th century), including the so-called Mausoleum of Fakhr al-Din Razi (possibly the tomb of Il-Arslan) and the Mausoleum of Sultan Tekesh.[55][56]

Ilkhanids (13th–14th centuries)

[edit]

From the 13th century to the early 16th century, Iran and Central Asia came under the control of two major dynasties descended from the Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan, the Ilkhanids (1256–1353) and the Timurids (1370–1506). This period saw the construction of some of the largest and most ambitious Iranian monuments of the Islamic world.[57] The Ilkhanids were initially traditional nomadic Mongols, but at the end of the 13th century, Ghazan Khan (r. 1295–1304) converted to Islam and aided a cultural and economic resurgence in which urban Iranian culture was of primary importance. Ilkhanid vassals, like the Muzaffarids and the Jalayirids, also sponsored new constructions.[57]

Ilkhanid architecture elaborated earlier Iranian traditions. In particular, greater attention was given to interior spaces and how to organize them. Rooms were made taller, while transverse vaulting was employed and walls were opened with arches, thus allowing more light and air inside.[57] Muqarnas, which was previously confined to covering limited transitional elements like squinches, was now used to cover entire domes and vaults for purely decorative effect. The Tomb of 'Abd al-Samad in Natanz (1307–8), for example, is covered inside by an elaborate muqarnas dome that is made from stucco suspended below the pyramidal vault that roofs the building.[57]

Brick remained the main construction material, but more color was added through the use of tile mosaic, which involved cutting monochrome tiles of different colors into pieces that were then fitted together to form larger patterns, especially geometric motifs and floral motifs.[57] Carved stucco decoration also continued. Some exceptional examples in Iran come from this period, including a wall of carved stucco in the Mausoleum of Pir-i Bakran in Linjan (near Isfahan),[30] and a mihrab added in 1310 to the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan. The latter is one of the masterpieces of Islamic sculptural art from this era, featuring multiple layers of deeply-carved vegetal motifs, along with a carved inscription.[58]

Various mosques were built or expanded during this period, usually following the four-iwan plan for congregational mosques (e.g. at Varamin and Kirman), except in the northwest, where cold winters discouraged the presence of an open courtyard, as at the Jameh Mosque of Ardabil (now ruined). Another hallmark of the Ilkhanid period is the introduction of monumental mosque portals topped by twin minarets, as seen at the Jameh Mosque of Yazd.[57] Caravanserais were built again, although the Khan al-Mirjan in Baghdad is the only surviving example.[57]

The most impressive monument to survive from this period is the Soltaniyeh Mausoleum built for Sultan Uljaytu (r. 1304–1317), a massive dome supported on a multi-level octagonal structure with internal and external galleries. Only the domed building remains today, missing much of its original turquoise tile decoration, but it was once the centerpiece of a larger religious complex including a mosque, a hospital, and living areas.[59] Smaller tombs and shrines in honour of local Sufis were also built or renovated by Ilkhanid patrons, such as the shrine of Bayazid Bastami in the town of Bastam, the aforementioned Mausoleum of Pir-i Bakran, and the aforementioned Tomb of Abd-al-Samad.[60] Also in Bastam, the Ilkhanids built a traditional tower tomb to house the remains of Uljaytu's infant son. Unusually, rather than being an independent structure, the tomb was erected behind the qibla wall of the town's main mosque – a configuration also found in some contemporary Mamluk architecture.[60]

Timurids (14th–15th centuries)

[edit]

The Timurid Empire, created by Timur (r. 1370–1405), oversaw another cultural renaissance. Timurid architecture continued the tradition of Ilkhanid architecture, building monuments once again on a grand scale and with lavish decoration made to impress, but they also refined previous designs and techniques.[59] Timurid rulers recruited the best craftsmen from their conquered territories or even forced them to move to the Timurid capital.[61]

Brick continued to be used as construction material. To cover large brick surfaces with colorful decoration, the banna'i technique was used to create geometric patterns and Kufic inscriptions at relatively low cost, while more expensive tile mosaic continued to be used for floral patterns.[57] Tiles were preferred on the outside, while interior walls could be covered with carved or painted plaster instead.[57]

Among the most important Timurid innovations was the more sophisticated and fluid arrangement of geometric vaulting.[59][57] Large vaults were divided by intersecting ribs into smaller vaults which could then be further subdivided or filled with muqarnas and other types of decoration. Muqarnas itself also became even more complex by using smaller individual cells to create the larger three-dimensional geometric plan. Visual balance could be achieved by alternating one type or pattern of decoration with another between the different subdivisions of the vault. By combining these vaulting techniques with a cruciform plan and by breaking the solid mass of supporting walls with open arches and windows, a strict division between dome, squinch, and wall was dissolved and an endless diversity of elaborate interior spaces could be created.[57]

The most significant preserved Timurid monuments are found in and around the cities of Khorasan and Transoxiana, including Samarkand, Bukhara, Herat, and Mashhad.[57] Timur's own monuments are distinguished by their size; notably, the Bibi Khanum Mosque and the Gur-i Amir Mausoleum, both in Samarkand, and his imposing but now-ruined Ak-Saray Palace at Shahr-i Sabz.[57] The Gur-i Amir Mausoleum and the Bibi Khanum Mosque are distinguished by their lavish interior and exterior decoration, their imposing portals, and their prominent dome. The domes are supported on tall, cylindrical drums and have a pointed, bulging profile, sometimes fluted or ribbed.[62]

Timur's successors built on a somewhat smaller scale, but under the patronage of Gawhar Shad, the wife of his son Shah Rukh (r. 1405–1447), Timurid architecture attained the height of sophistication during the first half of the 15th century.[57] Her monuments were mainly found in Mashhad and Herat,[57] though some have been destroyed or severely damaged since the 19th century, including her mausoleum and mosque complex (1417–1438). Some of the surviving vaulting and decoration inside her mausoleum is nonetheless indicative of its original quality.[63]

Under Ulugh Beg (r. 1447–1449), the Registan Square in Samarkand was first transformed into a monumental complex similar to what it is today. He built three structures around the square, of which only the Ulugh Beg Madrasa (1417–1420) survives today (two other monumental structures were erected around the square at later periods), with a large façade covered by a rich variety of decoration.[62]

Timurid patronage was of high importance in the history of art and architecture across a wide part of the Islamic world. The international Timurid style was eventually integrated into the visual culture of the rising Ottoman Empire in the west,[64] while to the east it was transmitted to the Indian subcontinent by the Mughals, who were descended from Timur.[65]

During the late 14th and 15th centuries, western Iran was dominated by two powerful Turkoman confederations, the Qara Qoyunlu and the Aq Qoyunlu. While few monuments sponsored by either faction have been preserved, what does remain shows that the Timurid style was already spreading westward during this period.[64] One of the most significant Qara Qoyunlu monuments is the Blue Mosque or Muzaffariya Mosque (1465) in Tabriz, now partly ruined. It has an unusual T-shaped layout around a central dome, not unlike the Ottoman Green Mosque in Bursa, and is decorated with a revetment of very high-quality tilework in six colours, including a deep blue.[66]

Safavids and Uzbeks (16th–18th centuries)

[edit]The Safavids, who forged a large Shi'i empire in the 16th century that encompassed all of Iran and some neighbouring regions, initially inherited the traditions of Timurid architecture. To adapt this tradition into a new imperial style, Safavid architects pushed it to an even grander scale.[67] Safavid architecture simplified Timurid architecture to an extent, creating large architectural ensembles that are arranged around more static, fixed perspectives that appear more ceremonial, with more uniform building exteriors and more streamlined vault designs.[67][59] At the same time, buildings were carefully planned and often given an open layout that made them easy to enjoy.[67] The most characteristic decoration was tile mosaic, applied on a grand scale. The decorative program often served to obscure rather than highlight the structural design of buildings.[59][67] This Safavid style took shape in Isfahan and subsequently spread to other parts of the empire.[67]

Relatively few Safavid monuments have been preserved from before the period prior to the reign of Shah Abbas I (r. 1588–1629).[59][67] The most important exception is the tomb and religious complex of Sheikh Safi al-Din in Ardabil. This complex had been in development since the time of Safi al-Din (d. 1334), who founded a Sufi order with which Isma'il I (r. 1501–1524), the first Safavid ruler, associated himself. Safavid additions to the site began in the early 16th century, when Isma'il's small domed tomb was built here. His successor, Tahmasp I (r. 1524–1576), carried out the first major Safavid expansion of the complex. The most important structure added was the Jannat Sarai, a large octagonal structure in the same tradition as the old Ilkhanid mausoleum in Soltaniyeh, perhaps originally intended to be the domed tomb of Tahmasp I. Abbas I also made further renovations and additions to the site after this.[68]

Contemporary with the Safavids in Iran were other dynasties and ruling groups in Central Asia, such as the Shaybanids and other Uzbek tribal leaders. Monumental buildings continued to be built here, drawing on the traditional Timurid style.[67] In Bukhara, the Shaybanids created the present Po-i-Kalyan complex, integrating the Qarakhanid-era Kalan Minaret, renovating the old mosque in 1514, and adding the large Mir-i 'Arab Madrasa (1535–6).[69] Later, in Samarkand, the local ruler Yalangtush Bi Alchin gave the Registan its current appearance by building two new madrasas across from Ulugh Beg's madrasa. The Sher-Dor Madrasa (1616–1636) imitates the form of the Ulugh Beg Madrasa, while the Tilla Kar Madrasa (1646–1660) is both a mosque and a madrasa.[62] Architectural activity became less significant in the region after the 17th century, with the exception of Khiva. The Friday mosque of Khiva, with its distinctive hypostyle hall of wooden columns, was rebuilt in this form in 1788–9.[67]

Safavid Isfahan

[edit]Abbas I made Isfahan his capital and embarked on the most ambitious program of construction of the Safavid period. As a result, a very large proportion of preserved Safavid monuments are concentrated in this one city. Abbas I moved the political and economic center of the city from its traditional location near the old Jameh Mosque to a new area near the Zayandeh River to the south, where a new planned city was created. It includes a sprawling Grand Bazaar, lined with caravanserais, which opens via a monumental portal onto a vast, rectangular public square, the Maidan-i Shah or Naqsh-e Jahan, laid out between 1590 and 1602.[67][30] The entire square is surrounded by a two-level arcade and symbolizes Abbas I's ambition to be one of the greatest sovereigns on the world stage. In addition to the bazaar's portal, three other buildings stand at the middle of each side of the square: the Sheikh Lutfallah Mosque (1603–1619), the Shah Mosque (1611–c. 1630), and the Ali Qapu, a palace gateway and pavilion begun c. 1597 and finished under Abbas II, c. 1660.[67][30]

The two mosques on the square are each entered via monumental portals, but due to the difference between the direction of the qibla and the orientation of the square, both mosques are built at an angle from it and their vestibules bend on the way in. Both have prayer halls covered by a single large, double-shelled dome, though the Shah Mosque's prayer hall is also flanked by two hypostyle halls.[30] Unlike in Timurid monuments, the dome interiors are not geometrically subdivided and have a uniform surface instead.[59] An effect of lightness is achieved instead by the transitional zone of arches, squinches, and windows, with the walls of the prayer hall in the Shah Mosque also pierced by open archways. On the outside, the domes have an "onion" shape (i.e. bulging on the sides and pointed on top).[30] While the Shah Mosque has minarets and a traditional central courtyard surrounded by four iwans, the Lutfallah Mosque has no minarets and is different from all other Safavid mosques by consisting only of the single domed chamber.[30] The interiors of both mosques are entirely covered in glazed tiles, predominantly blue, which were restored in the 1930s on the basis of the few remaining original tiles.[30]

To the west of the Maidan-i Shah square was a large palace complex of gardens and pavilions. The most important surviving pavilion, Chehel Sotoun ("Forty Columns"), is dated to 1647 by an inscription, but may have been established earlier. In 1706–7, a deep, broad porch with columns was added to it, giving it its present appearance. The other notable surviving pavilion, Hasht Behesht, mostly dates to the late 17th century.[67][30] To the west of the palace grounds is a long, wide avenue called the Chaharbagh ("Four Gardens") which ends in the south at the Si-o-se-pol ("Bridge of thirty-three arches") bridge, built in 1602. The bridge is lined with arcades and features a wide central lane for caravans and beasts of burden as well as side passages for pedestrians.[67] Further downstream, the Khwaju Bridge (1650) is one of the finest monuments of the reign of Abbas II. Like the Si-o-se-pol, it combines aesthetic effect with practical function, but it is more complex and represents the apex of Safavid bridge design. It has two levels, each with a wide central passage for caravans and side passages for pedestrians along its flanking arches. At the middle of the bridge is a wider viewing pavilion with an octagonal layout.[67][70]

These bridges connect the city centre with the south bank of the Zayandeh River, where royal Safavid hunting grounds were once located. After 1604, a Christian Armenian quarter, New Julfa, was also created here. Some 30 or so churches were built in the area, of which 13 survive today, dating to the 17th and early 18th centuries.[30] The churches imported Armenian features and combined them with the contemporary Safavid style,[30] as exemplified by the Vank Cathedral (or Holy Saviour Cathedral), dating in its current form to around 1656.[71]

Zands and Qajars (18th–early 20th centuries)

[edit]As the Safavids declined in the 18th century, the Zand dynasty made Shiraz its capital. Muhammad Karim Khan Zand, the dynasty's founder, created a grand square and built a new set of monuments, in a way similar to the Safavid construction projects in Isfahan, though on a smaller scale.[67] Among the surviving monuments of this project is the Vakil Mosque, begun in 1766 and restored in 1827, as well as a bazaar and a hammam (bathhouse).[67]

In northern Iran, the Qajars made their capital at Tehran. They continued to build mosques throughout the country with a traditional courtyard layout with four iwans, but with certain variations and the introduction of new features like clocktowers. The Qajars also expanded major shrines like the Imam Reza Shrine in Mashhad and the Fatima Masumeh Shrine in Qom.[67] In Shiraz (which came under Qajar rule in 1794), the Mosque of Nasir al-Mulk (1876–1888) has a traditional layout but exemplifies a new style of decorative tiles, painted in overglaze with images of flower bouquets in predominantly blue, pink, yellow, violet and green colors, sometimes on a white background. This type of tile decoration can also be seen at the Sepahsalar Mosque in Tehran (1881–1890).[67]

Of the Qajar palaces built in and around Tehran, the most famous is the Golestan Palace, which was both the administrative center and the shah's winter residence. Used by successive Qajar rulers, the palace underwent many modifications that illustrate the progressive changes over this period.[67] Traditional forms were still prevalent under Fath Ali Shah (r. 1797–1834), who commissioned the Marble Throne and installed it in a traditional audience hall fronted by columns.[67][72] The 19th century also saw the rise of revivalist trends. Qajar monarchs, including Fath Ali Shah, commissioned works that deliberately referenced Safavid and ancient Sasanian architecture, hoping to appropriate their symbolism of kingship and empire.[73]

Under Naser al-Din Shah (r. 1848–1896), new elements and styles of European inspiration began to be introduced, such as tall windows, pilasters, and formal staircases. At the Golestan Palace, he added the Shams ol-Emareh, a tall multi-leveled structure with two towers.[67][72] He also remodelled Tehran, demolishing the dense urban fabric in parts of the old city, as well as its historic walls, and replacing them with boulevards and open squares inspired by what he saw in his visits to Europe.[75][72]

At the beginning of the 20th century, during the last decades of Qajar rule and the early years of Pahlavi rule, revivalist trends continued to be popular and were employed in the design of both public and private buildings, including those commissioned by the rising bourgeoisie. This resulted in many examples of buildings across the country with an eclectic blend of stylistic features from both the Islamic and ancient Zoroastrian eras.[73]

Persian domes

[edit]

The Sassanid Empire initiated the construction of the first large-scale domes in Iran, with such royal buildings as the Palace of Ardashir and Dezh Dokhtar. After the Muslim conquest of the Sassanid Empire, the Persian architectural style became a major influence on Islamic societies and the dome also became a feature of Muslim architecture.

The Il-Khanate period provided several innovations to dome-building that eventually enabled the Persians to construct much taller structures. These changes later paved the way for Safavid architecture. The pinnacle of Il-Khanate architecture was reached with the construction of the Soltaniyeh Dome (1302–1312) in Zanjan, Iran, which measures 50 m in height and 25 m in diameter, making it the 3rd largest and the tallest masonry dome ever erected.[76] The thin, double-shelled dome was reinforced by arches between the layers.[77]

The renaissance in Persian mosque and dome building came during the Safavid dynasty, when Shah Abbas, in 1598, initiated the reconstruction of Isfahan, with the Naqsh-e Jahan Square as the centerpiece of his new capital.[78] Architecturally they borrowed heavily from Il-Khanate designs, but artistically they elevated the designs to a new level.

The distinct feature of Persian domes, which separates them from those domes created in the Christian world or the Ottoman and Mughal empires, was the use of colourful tiles, with which the exterior of domes are covered much like the interior. These domes soon numbered dozens in Isfahan and the distinct blue shape would dominate the skyline of the city. Reflecting the light of the sun, these domes appeared like glittering turquoise gems and could be seen from miles away by travelers following the Silk road through Persia.

This very distinct style of architecture was inherited from the Seljuq dynasty, who for centuries had used it in their mosque building, but it was perfected during the Safavids when they invented the haft- rangi, or seven colour style of tile burning, a process that enabled them to apply more colours to each tile, creating richer patterns, sweeter to the eye.[79] The colours that the Persians favoured were gold, white and turquoise patterns on a dark-blue background.[80] The extensive inscription bands of calligraphy and arabesque on most of the major buildings where carefully planned and executed by Ali Reza Abbasi, who was appointed head of the royal library and Master calligrapher at the Shah's court in 1598,[81] while Shaykh Bahai oversaw the construction projects. Reaching 53 meters in height, the dome of Masjed-e Shah (Shah Mosque) would become the tallest in the city when it was finished in 1629. It was built as a double-shelled dome, spanning 14 m between the two layers and resting on an octagonal dome chamber.[82]

-

Dome of Gur-i Emir Mausoleum in Samakand (early 14th century)

-

Example of a common shape of Persian dome at the Shah Mosque in Isfahan (early 17th century)

-

Modern dome architecture in the proposed mosque of Isfahan international convention center

Contemporary Iranian architecture

[edit]Contemporary architecture in Iran begins with the advent of the first Pahlavi period in the early 1920s. Some designers, such as Andre Godard, created works such as the National Museum of Iran that were reminiscent of Iran's historical architectural heritage. Others made an effort to merge the traditional elements with modern designs in their works. The Tehran University main campus is one such example. Others, such as Heydar Ghiai and Houshang Seyhoun, have tried to create completely original works, independent of prior influences.[84] Dariush Borbor's architecture successfully combined modern architecture with local vernacular.[85][86] The Azadi Tower, originally called the Shadyad Tower, was completed in 1971 and has since become one of the major landmarks of Tehran. Designed by Hossein Amanat, it incorporates forms and ideas from historic Iranian architecture.[87][88] Borj-e Milad (or Milad Tower), completed in 2007,[89] is the tallest tower in Iran and is the 24th tallest free-standing structure in the world.

-

Iran Senate House Traditional Persian mythology such as the chains of justice of Nowshiravan and essences of Iranian architecture have been incorporated by Heydar Ghiai to create a new modern Iranian architecture.

-

Tehran's Museum of Contemporary Arts designed by Kamran Diba is based on traditional Iranian elements such as Badgirs, and yet has a spiraling interior reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim.

-

Tehran University College of Social Sciences shows obvious traces of architecture from Persepolis.

Iranian architects

[edit]

The first professional association of Iranian architects, the Society of Iranian Diplomate Architects, was founded on 30 January 1945. Its founders were Iranian architects, including Vartan Avanessian, Mohsen Foroughi, and Keyghobad Zafar. Foreign architects had been very prominent in Iran during the early 20th century, and one of the new association's activities was the publication of a magazine, Architecte, which promoted Iranian architects.[90] In 1966, a new professional association was founded, the Association of Iranian Architects. Its founders included Vartan Avanessian, Abass Azhdari, Naser Badi, Abdelhamid Eshraq, Manuchehr Khorsandi, Iraj Moshiri, Ali Sadeq, and Keyghobad Zafar.[90]

Several Iranian architects have managed to win the prestigious A' Design Award 2018 in an unprecedented number of sections.[91] A number of Iranian architects have also won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, including:

- Bagh-e-Ferdowsi, Tehran. 1999–2001[92]

- New Life for Old Structures, Various locations. 1999–2001[92]

- Shushtar New Town, Shushtar. 1984–1986[93]

- Ali Qapu, Chehel Sutun, and Hasht Behesht, Isfahan. 1978–1980[94]

UNESCO designated World Heritage Sites

[edit]

The following is a list of World Heritage Sites designed or constructed by Iranians, or designed and constructed in the style of Iranian architecture:

- Inside Iran:

- Arg-é Bam Cultural Landscape, Kerman

- Naqsh-e Jahan Square, Isfahan

- Damavand, Mazandaran

- Pasargadae, Fars

- Persepolis, Fars

- Chogha Zanbil, Khuzestan

- Takht-e Soleyman, West Azerbaijan

- Dome of Soltaniyeh, Zanjan

- Behistun Inscription, Kermanshah province

- Outside Iran:

- Mausoleum of Sultan Sanjar, Turkmenistan[96][97]

- Ruins of Konye-Urgench, Turkmenistan[98][99]

- Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasavi, Kazakhstan

- Historic Centre of Baku, Azerbaijan

- Historic Centre of Ganja, Azerbaijan

- Historic Centre of Bukhara, Uzbekistan

- Historic Centre of Shahrisabz, Uzbekistan

- Itchan Kala of Khiva, Uzbekistan

- Samarkand, Uzbekistan

- Citadel, Ancient City and Fortress Buildings of Derbent, Daghestan, Russia

- Baha'i Gardens, Haifa, Israel

- Bibi-Heybat Mosque, Azerbaijan

- Tuba Shahi Mosque, Azerbaijan

- Palace of Shaki Khans, Shaki, Azerbaijan

See also

[edit]- Yakhchāl

- Ab anbar

- Windcatcher

- Great Wall of Gorgan

- Band-e Kaisar

- Construction industry of Iran

- Architecture of Azerbaijan

- Mughal architecture

- ArchNet, MIT/UT Austin's archive of Iranian architectural documents

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "برج آزادی پس از ۲۰ سال شسته میشود" (in Persian). BBC News فارسی. 18 July 2009. Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- ^ Arthur Upham Pope. Introducing Persian Architecture. Oxford University Press. London. 1971. p.1

- ^ Arthur Pope, Introducing Persian Architecture. Oxford University Press. London. 1971.

- ^ a b Arthur Upham Pope. Persian Architecture. George Braziller, New York, 1965. p.266

- ^ Arthur Upham Pope. Persian Architecture. George Braziller, New York, 1965. p.266

- ^ a b Arthur Upham Pope. Persian Architecture. George Braziller, New York, 1965. p.10

- ^ Nader Ardalan and Laleh Bakhtiar. Sense of Unity; The Sufi Tradition in Persian Architecture. 2000. ISBN 1-871031-78-8

- ^ Arthur Upham Pope. Persian Architecture. George Braziller, New York, 1965. p.9

- ^ Grigor 2021, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Jayyusi, Salma K.; Holod, Renata; Petruccioli, Attilio; Raymond, Andre (2008). The City in the Islamic World, Volume 94/1 & 94/2. BRILL. pp. 173–176. ISBN 9789004162402.

- ^ Sabk Shenasi Mi'mari Irani (Study of styles in Iranian architecture), M. Karim Pirnia. 2005. ISBN 964-96113-2-0 p.24. Page 39, however, considers "pre-Parsi" as a distinct style.

- ^ "Hatra | Iraq, History, & Facts". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- ^ "Hatra". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- ^ "Kermanshah, A Cradle of Civilization" (PDF). Iran Daily. August 9, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2007.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, p. 96.

- ^ Hill, Donald R. (1994). Islamic Science and Engineering. p. 10. ISBN 0-7486-0457-X.

- ^ a b Sabk Shenasi Mi'mari Irani (Study of styles in Iranian architecture), M. Karim Pirnia. 2005. ISBN 964-96113-2-0 pp.40-51

- ^ Fallāḥʹfar, Saʻīd (سعید فلاحفر). The Dictionary of Iranian Traditional Architectural Terms (Farhang-i vāzhahʹhā-yi miʻmārī-i sunnatī-i Īrān فرهنگ واژههای معماری سنتی ایران). Kamyab Publications (انتشارات کامیاب). Kāvushʹpardāz. 2000, 2010. Tehran. ISBN 978-964-2665-60-0 US Library of Congress LCCN Permalink: http://lccn.loc.gov/2010342544 pp.44

- ^ Pīrniyā, Muammah Karīm (2005). Sabk Shināsī-i miʻmārī-i Īrānī (Study of styles in Iranian architecture). Tehran: Surush-i Dānish. ISBN 964-96113-2-0.p.92-93 & p.94-129

- ^ Petersen 1996, p. 295.

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, Architecture (III. 661–c. 750)

- ^ Petersen 1996, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bloom & Blair 2009, Architecture (IV. c. 750–c. 900)

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Petersen 1996, pp. 24–25, 251.

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, Architecture

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, Stucco and plasterwork

- ^ a b c d Hattstein & Delius 2011, p. 110.

- ^ Bloom 2013, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bloom & Blair 2009, Isfahan

- ^ Kuban, Doğan (1974). The Mosque and Its Early Development. Brill. p. 22. ISBN 978-90-04-03813-4.

- ^ Herzig, Edmund; Stewart, Sarah (2011). Early Islamic Iran. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-78673-446-4.

- ^ a b Bloom & Blair 2009, Na῾in

- ^ Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the Sixth to the Eleventh Century (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9780582405257.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bloom & Blair 2009, Architecture (V. c. 900–c. 1250)

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, Muqarnas

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, Bukhara

- ^ Hillenbrand 1999b, p. 100.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, p. 348.

- ^ a b Hattstein & Delius 2011, pp. 368–369.

- ^ a b c Bosworth, C.E.; Hillenbrand, R.; Rogers, J.M.; Blois, F.C. de; Darley-Doran, R.E. (1960–2007). "Sald̲j̲ūḳids; VI. Art and architecture; 1. In Persia". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill. ISBN 9789004161214.

- ^ a b c Bloom & Blair 2009, Saljuq

- ^ Bonner, Jay (2017). Islamic Geometric Patterns: Their Historical Development and Traditional Methods of Construction. Springer. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-4419-0217-7.

- ^ a b Hattstein & Delius 2011, p. 354–359.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 140–144.

- ^ O'Kane, Bernard (1995). Domes Archived 2022-05-11 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Hillenbrand 1999b, p. 109.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 153–154.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, p. 363–364.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 146.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, p. 330–332.

- ^ a b Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 134.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, p. 336–337.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 150–152.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, p. 360–366.

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, Kunya-Urgench

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Bloom & Blair 2009, Architecture (VI. c. 1250–c. 1500)

- ^ Blair & Bloom 1995, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tabbaa, Yasser (2007). "Architecture". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill. ISBN 9789004161658.

- ^ a b Blair & Bloom 1995, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Blair & Bloom 1995, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Bloom & Blair 2009, Samarkand

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, Herat

- ^ a b Blair & Bloom 1995, p. 50.

- ^ Asher, Catherine B. (2020). "Mughal architecture". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill. ISSN 1873-9830.

- ^ Blair & Bloom 1995, pp. 50–52.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Bloom & Blair 2009, Architecture (VII. c. 1500–c. 1900)

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, pp. 507–509.

- ^ Blair & Bloom 1995, pp. 199–201.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, pp. 517–518.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, p. 518.

- ^ a b c Bloom & Blair 2009, Qajar

- ^ a b Grigor, Talinn (2017). "Kings and Traditions in Différance: Antiquity Revisited in Post-Safavid Iran". In Flood, Finbarr Barry; Necipoğlu, Gülru (eds.). A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 1089–1097. ISBN 9781119068662.

- ^ Grigor 2021, pp. 172–174.

- ^ Haghighi, Farzaneh (2018). Is the Tehran Bazaar Dead? Foucault, Politics, and Architecture. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-5275-1779-0.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Encyclopædia Iranica | Articles". Iranicaonline.org. 1995-12-15. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ Savory, Roger (1980). Iran under the Safavids. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 155. ISBN 0-521-22483-7.

- ^ Blake, Stephen P. (1999). Half the World, The Social Architecture of Safavid Isfahan, 1590–1722. Costa Mesa: Mazda. pp. 143–144. ISBN 1-56859-087-3.

- ^ Canby, Sheila R. (2009). Shah Abbas, The Remaking of Iran. London: British Museum Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7141-2456-8.

- ^ Canby, Sheila R. (2009). Shah Abbas, The Remaking of Iran. p. 36.

- ^ Hattstein, M.; Delius, P. (2000). Islam, Art and Architecture. Cologne: Köneman. pp. 513–514. ISBN 3-8290-2558-0.

- ^ Illustrated Dictionary of the Muslim World. Marshall Cavendish. 2011. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-7614-7929-1.

- ^ Diba, Darab; Dehbashi, Mozayan (2004). "Trends in Modern Iranian Architecture" (PDF). In Jodidio, Philip (ed.). Iran: Architecture for Changing Societies. Umberto Allemandi & C.

- ^ Architecture: formes + fonctions. 2010-11-10. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- ^ Michel Ragon, Histoire Mondiale de l'Architecture et de l'Urbanisme Modernes, vol. 2, Casterman, Paris, 1972, p. 356.

- ^ Amanat, Abbas (2017). Iran: A Modern History. Yale University Press. p. 667. ISBN 978-0-300-23146-5.

- ^ "برج آزادی پس از۲۰ سال شسته می شود" (in Persian). BBC News فارسی. 2009-07-18. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- ^ Shirazi, M. Reza (2018). Contemporary Architecture and Urbanism in Iran: Tradition, Modernity, and the Production of 'Space-in-Between'. Springer. p. 65. ISBN 978-3-319-72185-9.

- ^ a b Roudbari, Shawhin (2015). "Instituting architecture: A history of transnationalism in Iran's architecture profession, 1945–1995". In Gharipour, Mohammad (ed.). The Historiography of Persian Architecture. Routledge. pp. 173–183. ISBN 978-1-317-42721-6.

- ^ "Iranian Architects Among Winners Of Prestigious A' Design Award 2018". ifpnews.com. 2018-04-17. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- ^ a b Aga Khan Award for Architecture – Master Jury Report – The Eighth Award Cycle, 1999–2001 Archived 2007-06-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Aga Khan Award for Architecture: The Third Award Cycle, 1984–1986 Archived 2007-05-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (AKTC) Archived 2007-06-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Arthur Upham Pope, Persian Architecture, 1965, New York, p.16

- ^ Creswell, K. A. C. (1913). "The Origin of the Persian Double Dome". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 24: 94.

- ^ UNESCO Office Tashkent, and Georgina Herrmann. "The Archaeological Park 'Ancient Merv' Turkmenistan", UNESCO, 1998, p. 51–52 https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/886.pdf

- ^ Kuehn, S. 2007. "Tilework on 12th to 14th century funerary monuments in Urgench (Gurganj)", in Arts of Asia, Volume 37, Number 2, pages 112-129

- ^ "Kunya-Urgench". UNESCO World Heritage Center. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

Sources

[edit]- Blair, Sheila; Bloom, Jonathan M. (1995). The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250–1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06465-0.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila (2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (2013). The minaret. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748637256. OCLC 856037134.

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300218701.

- Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn (2001). Islamic Art and Architecture: 650–1250. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08869-4. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Flood, Finbarr Barry; Necipoğlu, Gülru, eds. (2017). A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture. Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 9781119068662.

- Hattstein, Markus; Delius, Peter, eds. (2011). Islam: Art and Architecture. h.f.ullmann. ISBN 9783848003808.

- Hillenbrand, Robert (1994). Islamic Architecture: Form, Function, and Meaning (Casebound ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231101325. OCLC 30319450.

- Hillenbrand, Robert (1999b). Islamic art and architecture. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20305-7.

- Petersen, Andrew (1996). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-20387-3.

- Grigor, Talinn (2021). The Persian Revival: The Imperialism of the Copy in Iranian and Parsi Architecture. Pennsylvania State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-08968-3.

Further reading

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Iran |

|---|

|

|

|

- Abdullahi Y.; Embi M. R. B (2015). Evolution of Abstract Vegetal Ornaments on Islamic Architecture. International Journal of Architectural Research: Archnet-IJAR. Archived from the original on 2019-01-21. Retrieved 2015-09-02.

- Yahya Abdullahi; Mohamed Rashid Bin Embi (2013). "Evolution of Islamic geometric patterns". Frontiers of Architectural Research. 2 (2). Frontiers of Architectural Research: Elsevier: 243–251. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2013.03.002.

- Carboni, S.; Masuya, T. (1993). Persian tiles. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Kleiss, Wolfgang (2015). Geschichte der Architektur Irans [History of Iranian Architecture]. Archäologie in Iran und Turan, volume 15. Berlin: Reimer, ISBN 978-3-496-01542-0.

- Encyclopedia Iranica on ancient Iranian architecture

- Encyclopedia Iranica on Stucco decorations in Iranian architecture

![Jamkaran Mosque, near Qom (21st century)[83]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f0/Jamkaran_Mosque-3855.jpg/120px-Jamkaran_Mosque-3855.jpg)