Patrick Cleburne

Patrick Cleburne | |

|---|---|

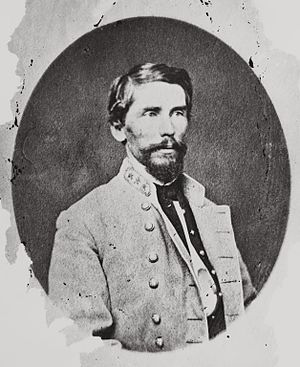

Cleburne in uniform, c. 1862 | |

| Birth name | Patrick Ronayne Cleburne |

| Nickname(s) | "Stonewall of the West" |

| Born | March 16, 1828 Ovens, County Cork, Ireland |

| Died | November 30, 1864 (aged 36) Franklin, Tennessee |

| Buried | 34°32′30″N 90°35′34″W / 34.54167°N 90.59278°W |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | British Army Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1846–1849 1861–1864 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 41st Regiment of Foot (1846-49) |

| Battles | |

| Signature | |

Major-General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne (/ˈkleɪbɜːrn/ KLAY-burn; March 16, 1828 – November 30, 1864)[1] was a senior officer in the Confederate States Army who commanded infantry in the Western Theater of the American Civil War.[2]

Born in Ireland,[1] Cleburne served in the 41st Regiment of Foot of the British Army after failing to gain entrance into Trinity College of Medicine, Dublin in 1846. He served at Fort Westmorland on Spike Island and was present on the island in 1849 when Queen Victoria visited Cork Harbour. Three years after joining the Army, he immigrated to the United States. At the beginning of the American Civil War, Cleburne sided with the Confederate States. He progressed from being a private soldier in the local militia to a division commander. He participated in many military campaigns, especially the Battle of Stones River, the Battle of Missionary Ridge and the Battle of Ringgold Gap. He was also present at the Battle of Shiloh. Known as the "Stonewall of the West", Cleburne was killed leading his men at the Battle of Franklin.

Early life

[edit]Patrick Ronayne Cleburne was born in Ovens, County Cork, Ireland the second son of Dr. Joseph Cleburne, a middle-class physician of Protestant Anglo-Irish ancestry. Patrick's mother died when he was 18 months old, and he was an orphan at 15. He followed his father into the study of medicine, but failed his entrance exam to Trinity College of Medicine in 1846. In response to this failure, he enlisted in the 41st Regiment of Foot of the British Army, subsequently rising to the rank of corporal.[3] Cleburne served at Fort Westmorland on Spike Island in Cork Harbour, a large fortress that was then being used as a convict depot. Seeing the wretched state of those filling the prison cells during the Great Irish Famine, Cleburne was further motivated to emigrate with his family to America.

Three years after joining the British Army, Cleburne bought his discharge and emigrated to the United States with two brothers and a sister. After spending a short time in Ohio, he settled in Helena, Arkansas, where he was employed as a pharmacist and was readily accepted into the town's social order.[3] During this time, Cleburne became close friends with Thomas C. Hindman, who later paralleled his course as a Confederate major general. The two men also formed a business partnership with William Weatherly to buy a newspaper, the Democratic Star, in December 1855.

In 1856, Cleburne and Hindman were both wounded by gunshots during a street fight in Helena with members of the Know-Nothing Party following a debate. Cleburne was shot in the back, turned around and shot one of his attackers, killing him. The attackers hid until Cleburne collapsed on the street and then left. After the two recovered, they appeared before a grand jury to respond to all charges brought against them. They were exonerated, and afterward, went to Hindman's parents' house in Mississippi.[4] By 1860, he was a naturalized citizen, a practicing lawyer, and very popular with the local residents.[5]

American Civil War

[edit]When the issue of secession reached a crisis, Cleburne sided with the Southern states. His choice was not due to any love of slavery,[6] which he claimed not to care about, but out of affection for the Southern people who had adopted him as one of their own. As the crisis mounted, Cleburne joined the local militia company (Yell Rifles) as a private soldier. He was soon elected captain.[4] He led the company in the seizure of the U.S. Arsenal at Little Rock in January 1861. When Arkansas left the Union, the Yell Rifles became part of the 1st Arkansas Infantry. Cleburne's regiment was assigned to the force under William Hardee, training in northeast Arkansas and conducting brief operations in southeast Missouri before Hardee's force was ordered to cross the Mississippi River and join Albert Sidney Johnston's Army of Central Kentucky in the fall 1861. The 1st Arkansas was designated the 15th Arkansas in late 1861. Cleburne was promoted to brigadier general on March 4, 1862.[4]

Johnston withdrew his army from Bowling Green, Kentucky, through Tennessee, and into Mississippi before electing to attack the invading Union forces under Ulysses S. Grant. Cleburne served at the Battle of Shiloh, leading a brigade on the left side of the Confederate line, as well as at the siege of Corinth. That fall, Cleburne and his men were transported to Tennessee in preparation of Braxton Bragg's Confederate Heartland Offensive. In that campaign, Cleburne was loaned to Edmund Kirby Smith, whose smaller army led the invasion. At the Battle of Richmond (Kentucky), Cleburne was wounded in the face when a minie ball pierced his left cheek, smashed several teeth, and exited through his mouth, but he recovered in time to re-join Hardee and Bragg and participate in the Battle of Perryville.[8][9] After the Army of Tennessee retreated to its namesake state in late 1862, Cleburne was promoted to division command and served at the Battle of Stones River, where his division advanced three miles as it routed the Union right wing and drove it back to the Nashville Pike and its final line of defense. He was promoted to major general on December 13.[2]

During the campaigns of 1863 in Tennessee, Cleburne and his soldiers fought at the Battle of Chickamauga. They successfully resisted a much larger Union force under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman on the northern end of Missionary Ridge during the Battle of Missionary Ridge, and Joseph Hooker at the Battle of Ringgold Gap in northern Georgia, in which Cleburne's men again protected the Army of Tennessee as it retreated to Tunnel Hill, Georgia. Cleburne and his troops received an official Thanks from the Confederate Congress for their actions during this campaign.[8]

Cleburne's strategic use of terrain, his ability to hold ground where others failed, and his talent in foiling the movements of the enemy earned him fame, and gained him the nickname "Stonewall of the West." Federal troops were quoted as dreading to see the blue flag of Cleburne's Division across the battlefield.[10] General Robert E. Lee referred to him as "a meteor shining from a clouded sky".[11]

Proposal for emancipation and enlistment of Blacks

[edit]By late 1863, it had become obvious to Cleburne that the Confederacy was losing the war because of the growing limitations of its manpower and resources.[12] In 1864, he dramatically called together the leadership of the Army of Tennessee and put forth the proposal to emancipate all slaves ("emancipating the whole race upon reasonable terms, and within such reasonable time") in order to "enlist their sympathies" and thereby enlist them in the Confederate Army to secure Southern independence.[13][14] Cleburne argued that emancipation did not have to include black equality, noting that "necessity and wise legislation" would ensure relations between blacks and whites would not materially change.[15] This proposal was met with polite silence at the meeting, and while word of it leaked out, it went unremarked, much less officially recognized.[12] From his letter outlining the proposal:[16]

Satisfy the negro that if he faithfully adheres to our standard during the war he shall receive his freedom and that of his race ... and we change the race from a dreaded weakness to a position of strength.

Will the slaves fight? The helots of Sparta stood their masters good stead in battle. In the great sea fight of Lepanto where the Christians checked forever the spread of Mohammedanism over Europe, the galley slaves of portions of the fleet were promised freedom, and called on to fight at a critical moment of the battle. They fought well, and civilization owes much to those brave galley slaves ... [Cleburne also cites the prowess of revolting slaves in Haiti and Jamaica] ... the experience of this war has been so far that half-trained negroes have fought as bravely as many other half-trained Yankees.

It is said that slavery is all we are fighting for, and if we give it up we give up all. Even if this were true, which we deny, slavery is not all our enemies are fighting for. It is merely the pretense to establish sectional superiority and a more centralized form of government, and to deprive us of our rights and liberties.

Cleburne's proposal was vigorously attacked as an "abolitionist conspiracy" by General William H. T. Walker, who strongly supported slavery and also saw Cleburne as a rival for promotion. Walker eventually persuaded the commander of the Army of Tennessee, General Braxton Bragg, that Cleburne was politically unreliable and undeserving of further promotion. "Three times in the summer of 1863 he was passed over for corps commander and remained a division commander until his death."[17]

Death and legacy

[edit]

Prior to the campaigning season of 1864, Cleburne became engaged to Susan Tarleton of Mobile, Alabama.[18] Their marriage was never to be, as Cleburne was killed during an ill-conceived assault (which he opposed) on Union fortifications at the Battle of Franklin, just south of Nashville, Tennessee, on November 30, 1864. He was last seen, after his horse was shot out from under him, advancing with his sword raised on foot toward the Union line.[19] Accounts later said that he was found just inside the Union line, and his body was carried back to a field hospital along the Columbia Turnpike. Confederate war records indicate he died either of a bullet to the abdomen,[2] or possibly through his heart. When Confederates found his body, he had been picked clean of any valuable items, including his sword, boots, and pocket watch.[20]

According to a letter written to General Cheatham from Judge Mangum after the war, Cleburne's remains were first laid to rest at Rose Hill Cemetery in Columbia, Tennessee. At the urging of Army Chaplain Bishop Quintard, Judge Mangum, staff officer to Cleburne and his law partner in Helena, Cleburne's remains were moved to St. John's Episcopal Church near Mount Pleasant, Tennessee, where they remained for six years. He had first observed St. John's during the Army of Tennessee's march into Tennessee during the campaign that led to the Battle of Franklin, and commented that it was the place he would like to be buried because of its great beauty and resemblance to his Irish homeland. In 1870, he was disinterred and returned to his adopted hometown of Helena, Arkansas, with much fanfare, and buried in the Confederate section of Maple Hill Cemetery, overlooking the Mississippi River.[21]

William J. Hardee, Cleburne's former corps commander, had this to say when he learned of his loss: "Where this division defended, no odds broke its line; where it attacked, no numbers resisted its onslaught, save only once; and there is the grave of Cleburne."[20]

Several geographic features are named after Patrick Cleburne, including Cleburne County in Alabama and Arkansas, and the city of Cleburne, Texas (which also features a statue of Patrick), though natives of the town call it "Klee-burn."[22] The location where he was killed in Franklin was reclaimed by preservationists, and is now known as Cleburne Park. Though the small monument in the park is often perceived as a monument to Cleburne, it actually is a marker to show where the Carter Family Cotton Gin once stood (the gin being an integral part of the Battle of Franklin, and the Carter House itself being the headquarters of Union Brigadier General Jacob D. Cox).

The Patrick R. Cleburne Confederate Cemetery is a memorial cemetery in Jonesboro, Georgia, which was named in honor of General Patrick Cleburne.[23]

During a 1994 interview (00:40:20) on Book TV, when asked his favorite "Civil War character" by C-SPAN's Brian Lamb, author Shelby Foote says: "It's easy to state who your favorites are because they're many people's favorites — Robert E. Lee, U.S. Grant, Stonewall Jackson, Tecumseh Sherman. But I have some favorites that are grievously neglected. One of them is an Arkansas general named Pat Cleburne, Patrick Ronayne Cleburne, from Arkansas [sic]. And he probably was the best division commander on either side, and in his day — he was killed at Franklin about a year before the end of the war — he was called the Stonewall Jackson of the West and well-known and adored by his men. He's been largely forgotten today. He's buried right there at Helena [Arkansas] where Crowley's Ridge comes to the Mississippi. I'm very fond of Cleburne. I got the same reaction at Cleburne's death that his men got. I was greatly saddened to lose him. You get a great fondness for these people or a severe dislike for them, and if you have a dislike for them, you lean over backward hoping not to let it show. I'm sure it does."[24]

See also

[edit]- List of American Civil War generals

- Bibliography of the American Civil War

- Bibliography of Ulysses S. Grant

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "Bride Park Cottage". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ a b c Eicher, p. 176.

- ^ a b Welsh, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c Hook, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Joslyn, p. 26.

- ^ Symonds, p. 44

- ^ "General Patrick R. Cleburne Memorial". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Fredriksen, pp. 105–07.

- ^ Major General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne, CSA (1828-1864)

- ^ Reynolds, pp. 244–47.

- ^ Rand, p. 138.

- ^ a b Connelly, pp. 318-19.

- ^ Daniel Mallock. "Cleburne's Proposal." North & South, vol. 11, no. 2, p. 64.

- ^ Hamner, Christopher. "Black Confederates." Teachinghistory.org Archived July 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 30 June 2011.

- ^ Levin 2005, pp 102-103

- ^ Official Records, Series I, vol. 52, Part 2, pp. 586–92.

- ^ TL Connelly. (2001) Autumn of Glory: The Army of Tennessee, 1862–1865 Pages 319–320.

- ^ Joslyn, p. 100.

- ^ Du Bose, p. 401.

- ^ a b Foote, p. 671.

- ^ Jacobson and Rupp, pp. 414, 434–35; Welsh, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 84.

- ^ Georgia Building Authority (1997). Patrick R. Cleburne Confederate Cemetery. Galileo. Retrieved September 1, 2010.

- ^ "[Stars in Their Courses] | C-SPAN.org".

References

[edit]- Connelly, Thomas L. Autumn of Glory: The Army of Tennessee 1862–1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971. ISBN 0-8071-2738-8.

- Du Bose, John Witherspoon. General Joseph Wheeler and the Army of the Tennessee. New York: Neale Publishing Company, 1912. OCLC 3997217.

- Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 3, Red River to Appomattox. New York: Random House, 1974. ISBN 0-394-74913-8.

- Fredriksen, John C. America's Military Adversaries: From Colonial Times to the Present. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-57607-603-2.

- Hook, Richard, and Philip R. N. Katcher. American Civil War Commanders. Vol. 4, Confederate Leaders in the West, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-84176-319-5.

- Jacobson, Eric A., and Richard A. Rupp. For Cause & for Country: A Study of the Affair at Spring Hill and the Battle of Franklin. Franklin, TN: O'More Publishing, 2007. ISBN 0-9717444-4-0.

- Joslyn, Mauriel. A Meteor Shining Brightly: Essays on the Life and Career of Major General Patrick R. Cleburne. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-86554-693-2.

- Levine, Bruce. Confederate emancipation: Southern plans to free and arm slaves during the Civil War. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-19803-367-2

- Rand, Clayton. Sons of the South. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1961. OCLC 1081994.

- Reynolds, John Hugh. Makers of Arkansas History. New York: Silver, Burdett and Co., 1905. OCLC 1610015.

- Symonds, Craig L. Stonewall of the West: Patrick Cleburne and the Civil War. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1997. ISBN 0-7006-0820-6.

- U.S. War Department. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

- Welsh, Jack D. Medical Histories of Confederate Generals. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-87338-853-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Buck, Irving A., Irving Ashby (1908). Cleburne and his command. New York : Neale Pub. Co. OCLC 367544780 (First published 1908 by Neale Publishing Co.)

- Nash, Charles Edward (1898). Biographical sketches of Gen. Pat Cleburne and Gen. T. C. Hindman. Little Rock, Ark., Tunnah & Pittard, printers. OCLC 3492441 (First published 1898 by Tunnah & Pittard)

- Purdue, Howell, and Elizabeth Purdue. Pat Cleburne, Confederate General: A Definitive Biography. Hillsboro, TX: Hill Junior College Press, 1973. ISBN 978-0-912172-18-7.

- Stewart, Bruce H. Invisible Hero: Patrick R. Cleburne. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-88146-108-4.

External links

[edit]

- 1828 births

- 1864 deaths

- 19th-century British Army personnel

- Military personnel from County Cork

- 41st Regiment of Foot soldiers

- American people of Anglo-Irish descent

- Confederate States Army major generals

- Confederate States of America military personnel killed in the American Civil War

- Irish Anglicans

- Irish emigrants to the United States

- Irish soldiers in the British Army

- Irish soldiers in the Confederate States Army

- People of Arkansas in the American Civil War

- People from Helena, Arkansas