Red herring

A red herring is something that misleads or distracts from a relevant or important question.[1] It may be either a logical fallacy or a literary device that leads readers or audiences toward a false conclusion. A red herring may be used intentionally, as in mystery fiction or as part of rhetorical strategies (e.g., in politics), or may be used in argumentation inadvertently.[2]

The term was popularized in 1807 by English polemicist William Cobbett, who told a story of having used a strong-smelling smoked fish to divert and distract hounds from chasing a rabbit.[3]

Logical fallacy

[edit]As an informal fallacy, the red herring falls into a broad class of relevance fallacies. Unlike the straw man, which involves a distortion of the other party's position,[4] the red herring is a seemingly plausible, though ultimately irrelevant, diversionary tactic.[5] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a red herring may be intentional or unintentional; it is not necessarily a conscious intent to mislead.[1]

The expression is mainly used to assert that an argument is not relevant to the issue being discussed. For example, "I think we should make the academic requirements stricter for students. I recommend you support this because we are in a budget crisis, and we do not want our salaries affected." The second sentence, though used to support the first sentence, does not address that topic.

Intentional device

[edit]In fiction and non-fiction, a red herring may be intentionally used by the writer to plant a false clue that leads readers or audiences toward a false conclusion.[6][7][8] For example, the character of Bishop Aringarosa in Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code is presented for most of the novel as if he is at the centre of the church's conspiracies, but is later revealed to have been innocently duped by the true antagonist of the story. The character's name is a loose Italian translation of "red herring" (aringa rosa; rosa actually meaning 'pink', and very close to rossa, 'red').[9]

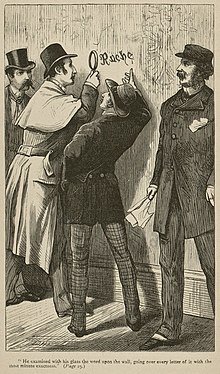

A red herring is found in the first Sherlock Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, where the murderer writes at the crime scene the word Rache ('revenge' in German), leading the police—and the reader—to mistakenly presume that a German was involved.

A red herring is often used in legal studies and exam problems to mislead and distract students from reaching a correct conclusion about a legal issue, intended as a device that tests students' comprehension of underlying law and their ability to properly discern material factual circumstances.[10]

History

[edit]

When I was a boy, we used [to], in order to draw off the harriers from the trail of a hare that we had set down as our own private property, get to her haunt[11] early in the morning, and drag a red-herring, tied to a string, four or five miles over hedges and ditches, across fields and through coppices,[a] till we got to a point, whence we were pretty sure the hunters would not return to the spot where they had [been] thrown off; and, though I would, by no means, be understood, as comparing the editors and proprietors of the London daily press to animals half so sagacious and so faithful as hounds, I cannot help thinking, that, in the case to which we are referring, they must have been misled, at first, by some political deceiver.

There is no fish species called "red herring", rather it is a name given to a particularly strong kipper, made from fish (typically herring) strongly cured in brine or heavily smoked. This process makes the fish particularly pungent smelling and, with strong enough brine, turns its flesh reddish.[13] In this literal sense, as a strongly cured kipper, the term can be dated to the late 13th century in the Anglo-Norman poem The Treatise by Walter of Bibbesworth, which then first appears in Middle English in the early 14th century: "He eteþ no ffyssh / But heryng red."[1] A 15th-century text known as the Heege Manuscript includes a joke about fighting oxen chopping one another apart until only "three red herrings" remain.[14]

The figurative sense of "red herring" has traditionally been said to originate from a supposed technique of training scent hounds.[13] There are variations of the story, but according to one version, the pungent red herring would be dragged along a trail until a puppy learned to follow the scent.[15] Later, when the dog was being trained to follow the faint odour of a fox or a badger, the trainer would drag a red herring (whose strong scent confuses the animal) perpendicular to the animal's trail to confuse the dog.[16] The dog eventually learned to follow the original scent rather than the stronger scent. A variation of this story is given, without mention of its use in training, in The Macmillan Book of Proverbs, Maxims, and Famous Phrases (1976), with the earliest use cited being from W. F. Butler's Life of Napier, published in 1849.[17] Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1981) gives the full phrase as "Drawing a red herring across the path", an idiom meaning "to divert attention from the main question by some side issue"; here, once again, a "dried, smoked and salted" herring when "drawn across a fox's path destroys the scent and sets the hounds at fault."[18] Another variation of the dog story is given by Robert Hendrickson (1994) who says escaping convicts used the pungent fish to throw off hounds in pursuit.[19]

According to a pair of articles by Professor Gerald Cohen and Robert Scott Ross published in Comments on Etymology (2008), supported by etymologist Michael Quinion and accepted by the Oxford English Dictionary, the idiom did not originate from a hunting practice.[13] Ross researched the origin of the story and found the earliest reference to using herrings for training animals was in a tract on horsemanship published in 1697 by Gerland Langbaine.[13] Langbaine recommended a method of training horses (not hounds) by dragging the carcass of a cat or fox so that the horse would be accustomed to following the chaos of a hunting party.[13] He says if a dead animal is not available, a red herring would do as a substitute.[13] This recommendation was misunderstood by Nicholas Cox, published in the notes of another book around the same time, who said it should be used to train hounds (not horses).[13] Either way, the herring was not used to distract the hounds or horses from a trail, rather to guide them along it.[13]

The earliest reference to using herring for distracting hounds is an article published on 14 February 1807 by radical journalist William Cobbett in his polemical periodical Political Register.[13][1][12][b]

According to Cohen and Ross, and accepted by the OED, this is the origin of the figurative meaning of red herring.[13] In the piece, William Cobbett critiques the English press, which had mistakenly reported Napoleon's defeat. Cobbett recounted that he had once used a red herring to deflect hounds in pursuit of a hare, adding "It was a mere transitory effect of the political red-herring; for, on the Saturday, the scent became as cold as a stone."[13] Quinion concludes: "This story, and [Cobbett's] extended repetition of it in 1833, was enough to get the figurative sense of red herring into the minds of his readers, unfortunately also with the false idea that it came from some real practice of huntsmen."[13]

Although Cobbett popularized the figurative usage, he was not the first to consider red herring for scenting hounds in a literal sense; an earlier reference occurs in the pamphlet Nashe's Lenten Stuffe, published in 1599 by the Elizabethan writer Thomas Nashe, in which he says "Next, to draw on hounds to a scent, to a red herring skin there is nothing comparable."[20] The Oxford English Dictionary makes no connection with Nashe's quote and the figurative meaning of red herring to distract from the intended target, only in the literal sense of a hunting practice to draw dogs toward a scent.[1]

The use of herring to distract pursuing scent hounds was tested on Episode 148 of the series MythBusters.[21] Although the hound used in the test stopped to eat the fish and lost the fugitive's scent temporarily, it eventually backtracked and located the target, resulting in the myth being classified by the show as "Busted".[22]

See also

[edit]- Attention theft

- Chekhov's gun

- Chewbacca defense

- Dead cat strategy

- Decoy

- False flag

- False positive

- False scent

- Foreshadowing

- Garden path sentence

- Ignoratio elenchi

- Judgmental language

- List of fallacies § Red herring fallacies

- MacGuffin

- Non sequitur (fallacy)

- Plot twist

- Red herring prospectus

- Shaggy dog story

- Snipe hunt (a fool's errand or wild goose chase)

- The Five Red Herrings

- Twelve Red Herrings

Notes

[edit]- ^ A coppice, US English copse, is a small group of trees growing very close to each other either naturally or due to being regularly trimmed back to stumps.

- ^ For the full original story by Cobbett, see the "Continental War" section in Cobbett, William (1807). Cobbett's political register. London: Richard Bagshaw. pp. 231–234.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "red herring, n." Oxford English Dictionary. OED Third Edition, September 2009. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ Red-Herring (15 May 2019). "Red Herring". txstate.edu. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ Dupriez, Bernard Marie (1991). A Dictionary of Literary Devices: Gradus, A–Z. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6803-3.

- ^ Hurley, Patrick J. (2011). A Concise Introduction to Logic. Cengage Learning. pp. 131–133. ISBN 978-0-8400-3417-5. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017.

- ^ Tindale, Christopher W. (2007). Fallacies and Argument Appraisal. Cambridge University Press. pp. 28–33. ISBN 978-0-521-84208-2.

- ^ Niazi, Nozar (2010). How To Study Literature: Stylistic And Pragmatic Approaches. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 142. ISBN 978-81-203-4061-9. Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Dupriez, Bernard Marie (1991). Dictionary of Literary Devices: Gradus, A-Z. Translated by Albert W. Halsall. University of Toronto Press. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-8020-6803-3. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Turco, Lewis (1999). The Book of Literary Terms: The Genres of Fiction, Drama, Nonfiction, Literary Criticism and Scholarship. UPNE. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-87451-955-6. Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Lieb, Michael; Mason, Emma; Roberts, Jonathan (2011). The Oxford Handbook of the Reception History of the Bible. Oxford University Press. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-19-967039-0. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017.

- ^ Sheppard, Steve, ed. (2005). The history of legal education in the United States: commentaries and primary sources (2nd print. ed.). Clark, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 978-1-58477-690-1.

- ^ According to the Collins English Dictionary, one meaning of haunt is a place at which one is regularly found, a hangout, and another meaning is a lair or feeding place of animals.

- ^ a b Cobbett, William (1807). Cobbett's Political Register. Vol. 11. London: Bagshaw. col. 232.

...we used [to], in order to draw off the harriers from the trail of a hare that we had set down as our own private property, get to her haunt early in the morning, and drag a red-herring, tied to a string, four or five miles over hedges and ditches...

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Quinion, Michael (2002–2008). "The Lure of the Red Herring". World Wide Words. Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ Almeroth-Williams, Tom (31 May 2023). "'Bawdy bard' manuscript reveals medieval roots of British comedy". University of Cambridge. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Nashe, Thomas. (1599) Nashes Lenten Stuffe Archived 15 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine "Next, to draw on hounds to a sent, to a redde herring skinne there is nothing comparable." (Since Nashe makes this statement not in a serious reference to hunting but as an aside in a humorous pamphlet, the professed aim of which is to extol the wonderful virtues of red herrings, it need not be evidence of actual practice. In the same paragraph he makes other unlikely claims, such as that the fish dried and powdered is a prophylactic for kidney or gallstones.)

- ^ Currall, J.E.P; Moss, M.S.; Stuart, S.A.J. (2008). "Authenticity: a red herring?" (PDF). Journal of Applied Logic. 6 (4): 534–544. doi:10.1016/j.jal.2008.09.004. ISSN 1570-8683.

- ^ Stevenson, Burton (ed.) (1976) [1948] The Macmillan Book of Proverbs, Maxims, and Famous Phrases New York: Macmillan. p. 1139. ISBN 978-0-02-614500-8

- ^ Evans, Ivor H. (ed.) (1981) Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (Centenary edition, revised) New York: Harper & Row. p.549. ISBN 978-0-06-014903-1

- ^ Hendrickson, Robert (2000). The Facts on File Encyclopedia of Word and Phrase Origins. United States: Checkmark.

- ^ Nashe, Thomas (1599) Praise of the Red Herring Archived 15 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine In: William Oldys and John Malham (Eds) The Harleian miscellany Archived 30 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine Volume 2, Printed for R. Dutton, 1809. p. 331.

- ^ MythBusters: Season 9, Episode 1 – Hair of the Dog at IMDb

- ^ "Episode 148: Hair of the Dog". MythBusters Results. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of red herring at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of red herring at Wiktionary