Resignation of Pope Benedict XVI

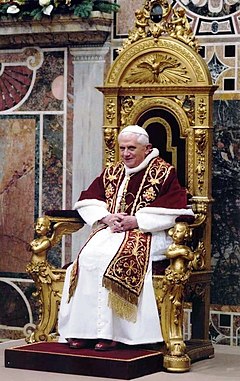

Pope Benedict XVI in 2011. | |

| Date | 28 February 2013 |

|---|---|

| Time | 20:00 (CET) |

| Cause | Deteriorating strength due to old age and the physical and mental demands of the papacy |

| Outcome |

|

The resignation of Pope Benedict XVI took effect on 28 February 2013 at 20:00 CET, following Benedict's announcement of it on 11 February.[1][2][3] It made him the first pope to relinquish the office[note 1] since Gregory XII was forced to resign in 1415[4] to end the Western Schism, and the first pope to voluntarily resign since Celestine V in 1294.[5]

All other popes in the modern era have held the position from election until death.[6] Benedict resigned at the age of 85, citing declining health due to old age.[7] The conclave to select his successor began on 12 March 2013[8] and elected cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, Archbishop of Buenos Aires, Argentina, who took the name of Francis.

Benedict chose to be known as "Pope emeritus" upon his resignation, and he retained this title until his death in December 2022.[9][10]

Announcement

[edit]On 11 February 2013, the World Day of the Sick, a Vatican holy day, Pope Benedict XVI announced his intention to resign at the Apostolic Palace in the Sala del Concistoro, at an early morning gathering held to announce the date of the canonisation of 800 Catholic martyrs.[11][12][13] Speaking in Latin, he told the attendees that he had made "a decision of great importance for the life of the church".[2][14] He cited his deteriorating strength due to old age and the physical and mental demands of the papacy.[7] He also declared that he would continue to serve the Church "through a life dedicated to prayer".[7]

Two days later, he presided over his final public Mass, Ash Wednesday services that ended with congregants bursting into a "deafening standing ovation that lasted for minutes"[15] while the pontiff departed St. Peter's Basilica.[16] On 17 February 2013, Benedict, speaking in Spanish, requested prayers for himself and the new pope from the crowd in St. Peter's Square.[17]

Post-papacy

[edit]According to Vatican spokesman Federico Lombardi, Benedict would not have the title of cardinal upon his retirement and would not be eligible to hold any office in the Roman Curia.[18][19] On 26 February 2013, Father Lombardi stated that the pope's style and title after resignation are His Holiness Benedict XVI, Roman Pontiff Emeritus, or Pope Emeritus.[20][21] In later years, Benedict expressed his desire to be known simply as "Father Benedict" in conversation.[22]

He continued to wear his distinctive white cassock without the mozzetta. Instead of the red papal shoes, he wore a pair of brown shoes that he received during a state visit to Mexico. Cardinal Camerlengo Tarcisio Bertone destroyed the Ring of the Fisherman and the lead seal of Benedict's pontificate. Benedict wore a regular ecclesiastical ring.[20]

After his resignation, Benedict took up residence in the Papal Palace of Castel Gandolfo. As the Swiss Guard serves as the personal bodyguard to the pope, their service at Castel Gandolfo ended with Benedict's resignation.[20] The Vatican Gendarmerie ordinarily provides security at the Papal summer residence; they became solely responsible for the former pope's personal security.[20] Benedict moved permanently to Vatican City's Mater Ecclesiae on 2 May 2013, a monastery previously used by nuns for stays of up to several years.[23]

Benedict XVI lived in the monastery until his death on 31 December 2022. He died there after being ill for several days. After his funeral on 5 January 2023 in St. Peter's Square, he was buried in a tomb next to his predecessors underneath St. Peter's Basilica.

Reactions

[edit]State

[edit]Australia's Prime Minister Julia Gillard,[24] Brazil's President Dilma Rousseff,[25] Canada's Prime Minister Stephen Harper,[26] Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel,[27] United Kingdom's Prime Minister David Cameron[28] and United States' President Barack Obama[29] praised Benedict and his pontificate; while Italy's Prime Minister Mario Monti[30] and Philippines' President Benigno Aquino III[31] expressed shock and regret, respectively.

Religious

[edit]Catholic

[edit]Cardinal Walter Brandmüller revealed that he initially thought the news of the renunciation was a "carnival joke", according to an interview he gave with the Germany daily newspaper, Bild.[32]

Metropolitan Archbishop of Lagos Alfred Adewale Martins said of the resignation:[33]

We do not have this sort of event happening every day. But at the same time, we know that the Code of Canon Law promulgated in 1983 makes provision for the resignation of the pope, if he becomes incapacitated or, as with Benedict XVI, if he believes he is no longer able to effectively carry out his official functions as head of the Roman Catholic Church due to a decline in his physical ability. This is not the first time that a pope would resign. In fact, we have had not less than three who resigned, including Pope Celestine V in 1294 and Pope Gregory XII in 1415. Pope Benedict XVI was not forced into taking that decision. Like he said in his own words, he acted with "full freedom", being conscious of the deep spiritual implication of his action. ...By his decision, the Holy Father has acted gallantly and as such we must commend and respect his decision.

Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan, the archbishop of New York, said that Benedict "brought a listening heart to victims of sexual abuse".[29][34]

One year before the pope's resignation, historian Jon M. Sweeney spoke of Benedict's connection to Celestine V in his book,The Pope Who Quit, how Benedict's comment when he became pope, "Pray for me that I may not flee for fear of the wolves", recalled a similar comment made by Celestine. Sweeney also compared and contrasted other aspects of the two popes' personalities and tenures leader of the church.[35]

Jewish

[edit]A spokesman for Yona Metzger, the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Israel, stated: "During his period there were the best relations ever between the [Catholic] Church and the chief rabbinate, and we hope that this trend will continue. I think [Benedict] deserves a lot of credit for advancing inter-religious links the world over between Judaism, Christianity and Islam." He also said that Metzger wished Benedict XVI "good health and long days."[36]

Buddhist

[edit]Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama and spiritual head of the Gelug sect of Tibetan Buddhism, expressed sadness over the resignation, while noting "his decision must be realistic, for the greater benefit to concern the people."[37]

Other authors

[edit]New York Times columnist Ross Douthat expressed that "nothing in his papacy became him like the leaving of it: His stunning 2013 resignation was the kind of revolutionary gesture that the church so badly needed."[38] On Catholic Family News, Roberto de Mattei concluded: "The resignation of Benedict XVI [...] is for me the symbol of the surrender of the Church to the world."[39]

It was reported at the time in La Repubblica that the pope's resignation was linked to a "gay mafia" operating within the Vatican: an underground network of high-ranking homosexual clergy, holding sex parties in Rome and the Vatican, and involved with corruption in the Vatican Bank. The pope's resignation was supposedly prompted by a 300-page dossier on the Vatican leaks scandal.[40][41] In a 2016 book, The Last Conversations, the Pope Emeritus downplayed the "gay mafia" rumour, describing it as a group of four or five people who were seeking to influence Vatican decisions that he had succeeded in breaking up.[42][43]

The Code of Canon Law promulgated in 1983 introduced for the first time a distinction between the Latin juridical institutes of the munus petrinum (literally "the gift of St. Peter", which means: "to be the Pope") and the ministerium petrinum (literally "the ministry of St. Peter", which means: "to do the Papal office", e.g. to sign Papal documents and to appoint bishops and cardinals). The Pope has the faculty to choose to leave the munus or only the ministerium: giving up the munus the Pope automatically refuses also the ministerium, whereas the vice versa is not possible.

According to the Italian bestseller titled Codice Ratzinger and to Stefano Violi, professor of Canon Law at the Theological Faculty of Emilia Romagna and at the Theological Faculty of Lugano, Benedict XVI gave up only the ministerium (as it is provided by the canon 332 §2) and not the munus.[44] The Papacy entered in the state of the Impeded See (in Latin: Sedes impedita ).[45] According to Vittorio Messori, this act was coherent with the choice of keeping the title of Pope emeritus.[46]

Final week

[edit]

Benedict XVI delivered his final Angelus on Sunday, 24 February. He told the gathered crowd, who carried flags and thanked the pope, "Thank you for your affection. [I will take up a life of prayer and meditation] to be able to continue serving the church."[47] The pope appeared for the last time in public during his regular Wednesday audience on 27 February 2013.[48][49] By 16 February, 35,000 people had already registered to attend the audience.[50] On the evening of 27 February there was a candlelight vigil to show support for Pope Benedict XVI at St. Peter's Square.[51] On his final day as pope, Benedict held an audience with the college of Cardinals, and at 16:15 (4:15 pm) local time he boarded a helicopter and flew to Castel Gandolfo. At about 17:30 (5:30 pm), he addressed the masses from the balcony for the last time as pope.[52] After this speech Benedict waited out the final hours of his papacy, which ended at 20:00 CET (8:00 pm) and promptly the see of Rome became vacant.[53]

Benevacantism

[edit]An uncertain number of people believed that the resignation of Benedict XVI was not valid, and that he therefore never resigned, that Pope Francis is an antipope and Benedict XVI still remained pope until 31 December 2022. Such a position was called "Benevacantism" (a portmanteau of "Benedict” and "sedevacantism"), "resignationism", or "Beneplenism".[54] Supporters of this position asserted that the phrasing or grammar of Benedict XVI's resignation statement, given in Latin, did not effectively remove him from office of the papacy.[55] This position became impossible to be held as of the death and funeral of Pope Benedict XVI, while Francis continued living.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Formally "renounce", from the Latin renuntiet (cf. canon 332 §2, 1983 Code of Canon Law)

References

[edit]- ^ Cullinane, Susannah (12 February 2013). "Pope Benedict XVI's resignation explained". CNN. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ a b Davies, Lizzy; Hooper, John; Connelly, Kate (11 February 2013). "Pope Benedict XVI resigns due to age and declining health". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ "BBC News – Benedict XVI: 10 things about the Pope's retirement". Bbc.co.uk. 2 May 2013. Archived from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Messia, Hada (11 February 2013). "Pope Benedict to resign at the end of the month, Vatican says". CNN. Archived from the original on 19 March 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ de Souza, Raymond J. (12 February 2013). "The Holy Father takes his leave". The National Post. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Pope Benedict XVI in shock resignation". BBC News. BBC. 11 February 2013. Archived from the original on 28 February 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ a b c "Pope Benedict XVI announces his resignation at end of month". Vatican Radio. 11 February 2013. Archived from the original on 11 February 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ "Conclave to begin Tuesday March 12th". Vatican Radio. 8 March 2013. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013.

- ^ "Benedict XVI will be 'Pope emeritus'". The Vatican Today. Archived from the original on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

Benedict XVI will be "Pontiff emeritus" or "Pope emeritus", as Fr. Federico Lombardi, S.J., director of the Holy See Press Office, reported in a press conference on the final days of the current pontificate. He will keep the name of "His Holiness, Benedict XVI" and will dress in a simple white cassock without the mozzetta (elbow-length cape).

- ^ Petin, Edward (26 February 2013). "Benedict's New Name: Pope Emeritus, His Holiness Benedict XVI, Roman Pontiff Emeritus". Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ Davies, Lizzy (12 May 2013). "Pope Francis completes contentious canonisation of Otranto martyrs". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ "Pope convokes consistory for canonization of three Blessed". The Vatican Today. 4 February 2013. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Pope will announce on Monday date for canonization for over 800 saints". Rome Reports. 9 February 2013. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013.

- ^ Lavanga, Claudio; McClam, Erin; Jamieson, Alastair. "Pope Benedict XVI, citing deteriorating strength, will step aside Feb. 28". NBC News. Archived from the original on 11 February 2013.

- ^ Cowell, Alan (13 February 2013). "Pope Ushers in Lent, Making Its Message of Sacrifice Personal This Year". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- ^ Ralph, Talia (13 February 2013). "Pope Benedict XVI leads his final mass on Ash Wednesday". GlobalPost. Archived from the original on 1 March 2013.

- ^ "Pope Benedict tells cheering crowd to pray 'for me and next pope'". NBC News. Archived from the original on 20 February 2013.

- ^ Glatz, Carol; Wooden, Cindy (12 February 2013). "Benedict will be prayerful presence in next papacy, spokesman says". Catholic News Service. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013.

- ^ Pullella, Phillip (15 February 2013). "Pope will have security, immunity by remaining in the Vatican". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Benedict XVI Will Be Pope Emeritus". Vatican Information Service. 26 February 2013. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013.

- ^ "Benedict XVI Will Be Pope Emeritus". The Catholic News. 27 February 2013. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ The request of a retired pope – simply call me 'Father Benedict', Catholic News Agency, accessed 13 April 2018

- ^ "Dopo le dimissioni il Papa si ritirerà presso il monastero Mater Ecclesiae fondato nel '94 per volontà di Wojtyla" (in Italian). Il Messagero. 11 February 2013. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Pope's resignation historic, says Prime Minister Julia Gillard". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013.

- ^ "President Dilma Rousseff says she respects Pope's decision to retire". www.ebc.com.br. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014.

- ^ Prime Minister's Office (11 February 2013). "Statement by the Prime Minister of Canada on the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI". Prime Minister of Canada's Office. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ Germany and Europe hail retiring Pope Benedict XVI Archived 10 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Deutsche Welle, 11 February 2013

- ^ "Statement from Prime Minister David Cameron following the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI". 10 Downing Street. 11 February 2013. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ a b Pope Benedict's 'selfless leadership' praised by US church leaders –President pays tribute to pope's work while senior Catholics say Benedict 'brought a listening heart to victims of sexual abuse' Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 11 February 2013

- ^ Stanglin, Doug (11 February 2013). "World leaders surprised, but respect pope's decision". USA Today. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ gov.ph (11 February 2013). "Statement of The Presidential Spokesperson on the Pope's resignation". Gov.ph. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "Emeritus Pope Benedict denies his resignation was a 'carnival joke'". Breaking News. 21 September 2018. Archived from the original on 27 February 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ "Lessons on Pope Benedict XVI's Resignation". Ngrguardiannews.com. 24 February 2013. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "Pope Benedict XVI Resigns: President Obama, Italian Prime Minister, Other World and Church Leaders React". Abcnews.go.com. 11 February 2013. Archived from the original on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "Pope resigning: Historian Jon M. Sweeney shares the story behind the last pope who quit". The Christian Science Monitor. 13 February 2013. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ "As pope steps down, chief rabbi lauds Vatican ties". The Jerusalem Post. 21 November 2011. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ "Dalai Lama saddened by resignation of Pope Benedict XVI". Web India 123. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014.

- ^ Douthat, Ross Gregory. To Change the Church: Pope Francis and the Future of Catholicism (pp. 16–17). Simon & Schuster. 2018

- ^ de Mattei, Roberto (January 2019). "Socci's Thesis Falls Short". Catholic Family News (review of Antonio Socci's book The Secret of Benedict XVI). Translated by Pellegrino, Giuseppe. Niagara Falls, ON. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ "Papal resignation linked to inquiry into 'Vatican gay officials', says paper". the Guardian. 22 February 2013.

- ^ Abad-Santos, Alexander (22 February 2013). "Did a Secret Vatican Report on Gay Sex and Blackmail Bring Down the Pope?". The Atlantic.

- ^ "In memoirs, ex Pope Benedict says Vatican 'gay lobby' tried to wield power: report". Reuters. 1 July 2016 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ Agency, Catholic News. "Benedict XVI discusses resignation, "gay mafia," Pope Francis in new book-length interview". www.catholicworldreport.com.

- ^ Stefano Violi. "La rinuncia di Benedetto XVI. Tra storia, diritto e coscienza". Rivista Teologica di Lugano. XVIII (2 / 2013). Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Marco Tosatti (28 August 2021). "Benedict's Renunciation and the Question of the "Impeded See"". Stilum Curiae.

- ^ Vittorio Messori (28 May 2014). "Ecco perché abbiamo davvero due papi". Corriere della Sera.

- ^ "Pope Benedict leads final public prayer, local media buzzes with scandal - CNN.com". Edition.cnn.com. 24 February 2013. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "Pope Benedict speaks of church's stormy waters in final papal audience - CNN.com". Edition.cnn.com. 27 February 2013. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "Some FAQ's on the Pope's Resignation". Zenit News Agency. 20 February 2013. Archived from the original on 25 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ "Thousands flocking to Rome to bid Benedict XVI farewell on Feb. 27th". news.va. 16 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ "Appello: Luce e silenzio per il Papa (Appeal: Candlelight and Silence for the Pope)" (in Italian). culturacattolica.it. 13 February 2013. Archived from the original on 25 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ "Text of final greeting on Feb. 28". Vatican.va. 28 February 2013. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Winfield, Nicole; D'Emilio, Frances (28 February 2013). "Now a 'simple pilgrim,' Benedict resigns papacy". Dallas Morning News. Dallas, TX. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Feser, Edward (14 April 2022). "Benevacantism is scandalous and pointless". The Catholic World Report.

- ^ "Benedict XVI's big decision: Can a pope really just resign?". The Pillar. 2 January 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Caldwell, Zelda (2 January 2023). "In stepping down, Benedict XVI carved out new role as 'contemplative' pope". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- Condon, Ed. (2 January 2023). "Pope Benedict's most important legacy is Francis". The Pillar. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

External links

[edit]- "Declaratio, 11 February 2013 – Benedict XVI" (English translation). Vatican State: Holy See. 11 February 2013.