Tartan

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Scotland |

|---|

|

| People |

| Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

Tartan (Scottish Gaelic: breacan [ˈpɾʲɛxkən]) is a patterned cloth with crossing horizontal and vertical bands in multiple colours, forming simple or complex rectangular patterns. Tartans originated in woven wool, but are now made in other materials. Tartan is particularly associated with Scotland, and Scottish kilts typically have tartan patterns. The earliest surviving samples of tartan-style cloth are around 3,000 years old and were discovered in Xinjiang, China.

Outside of Scotland, tartan is sometimes also known as "plaid" (particularly in North America); however, in Scotland, a plaid is a large piece of tartan cloth which can be worn several ways.

Traditional tartan is made with alternating bands of coloured (pre-dyed) threads woven in usually matching warp and weft in a simple 2/2 twill pattern. Up close, this pattern forms alternating short diagonal lines where different colours cross; from further back, it gives the appearance of new colours blended from the original ones. The resulting blocks of colour repeat vertically and horizontally in a distinctive pattern of rectangles and lines known as a sett.

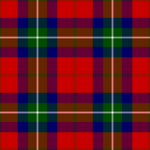

Scottish tartan was originally associated with the Highlands. Early tartans were only particular to locales, rather than any specific Scottish clan; however, because clans lived in and controlled particular districts and regions, then informally, people could roughly identify certain clans and families through the patterns associated with their own locality. Like other materials, tartan designs were produced by local weavers for local tastes, using the most available natural dyes.

The Dress Act 1746 attempted to bring the warrior clans there under government control by banning Highland dress for all civilian men and boys in the Highlands, as it was then an important element of Gaelic Scottish culture.

When the law was repealed in 1782, tartan was no longer ordinary dress for most Highlanders. It was adopted more widely as the symbolic national dress of all Scotland when King George IV wore a tartan kilt in his 1822 visit to Scotland; it was promoted further by Queen Victoria. This marked an era of rather politicised "tartanry" and "Highlandism".

While the first uniform tartan is believed to date to 1713 (with some evidence of militia use earlier), it was not until around the early 19th century that patterns were created for specific Scottish clans;[1] most of the traditional ones were established between 1815 and 1850. The Victorian-era invention of artificial dyes meant that a multitude of patterns could be produced cheaply; mass-produced tartan fashion cloth was applied to a nostalgic (and increasingly aristocratic, and profitable) view of Scottish history.

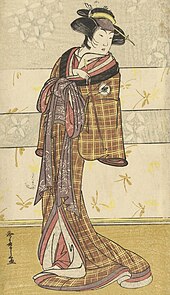

Today tartan is no longer limited to textiles, but is also used as a name for the pattern itself, regardless of medium. The use of tartan has spread outside Scotland, especially to countries that have been influenced by Scottish culture. However, tartan-styled patterns have existed for centuries in some other cultures, such as Japan, where complex kōshi fabrics date to at least the 18th century, and Russia (sometimes with gold and silver thread) since at least the early 19th century. Maasai shúkà wraps, Bhutanese mathra weaving, and Indian madras cloth are also often in tartan patterns, distinct from the Scottish style.

Etymology and terminology

[edit]The English and Scots word tartan is possibly derived from French tiretaine meaning 'linsey-woolsey cloth'.[2][3][4] Other hypotheses are that it derives from Scottish Gaelic tarsainn or tarsuinn, meaning 'across' or 'crossing over';[3][4] or from French tartarin or tartaryn (occurring in 1454 spelled tartyn)[5] meaning 'Tartar cloth'.[2] It is unrelated to the superficially similar word tarlatan, which refers to a very open-weave muslin similar to cheesecloth. Tartan is both a mass noun ("12 metres of tartan") and a count noun ("12 different tartans").

Today, tartan refers to coloured patterns, though originally did not have to be made up of a pattern at all, as it referred to the type of weave; as late as the 1820s, some tartan cloth was described as "plain coloured ... without pattern".[6][7] Patterned cloth from the Gaelic-speaking Scottish Highlands was called breacan, meaning 'many colours'. Over time, the meanings of tartan and breacan were combined to describe a certain type of pattern on a certain type of cloth.[7]

The pattern of a particular tartan is called its sett. The sett is made up of a series of lines at specific widths which cross at right angles and blend into each other;[7] the longer term setting is occasionally used.[8] Sett can refer to either the minimal visual presentation of the complete tartan pattern or to a textual representation of it (in a thread count).[7]

Today tartan is used more generally to describe the pattern, not limited to textiles, appearing on media such as paper, plastics, packaging, and wall coverings.[9][7][1][10]

In North America, the term plaid is commonly used to refer to tartan.[11][12][13][a] Plaid, derived from the Scottish Gaelic plaide meaning 'blanket',[16][b] was first used of any rectangular garment, sometimes made up of tartan,[c] which could be worn several ways: the belted plaid (breacan féile) or "great kilt" which preceded the modern kilt; the arisaid (earasaid), a large shawl that could be wrapped into a dress; and several types of shoulder cape, such as the full plaid and fly plaid. In time, plaid was used to describe blankets themselves.[12] In former times, the term plaiding[20] or pladding[21] was sometimes used to refer to tartan cloth.

Weaving and design

[edit]Weaving construction

[edit]

The Scottish Register of Tartans provides the following summary definition of tartan:[22]

Tartan (the design) is a pattern that comprises two or more different solid-coloured stripes that can be of similar but are usually of differing proportions that repeat in a defined sequence. The sequence of the warp colours (long-ways threads) is repeated in same order and size in the weft (cross-ways threads). The majority of such patterns (or setts) are symmetrical, i.e. the pattern repeats in the same colour order and proportions in every direction from the two pivot points. In the less common asymmetric patterns, the colour sequence repeats in blocks as opposed to around alternating pivots but the size and colour sequence of warp and weft remain the same.

In more detail, traditional tartan cloth is a tight, staggered 2/2 twill weave of worsted wool: the horizontal weft (also woof or fill) is woven in a simple arrangement of two-over-two-under the fixed, vertical warp, advancing one thread at each pass.[15] As each thread in the weft crosses threads in the warp, the staggering by one means that each warp thread will also cross two weft threads. The result, when the material is examined closely, is a characteristic 45-degree diagonal pattern of "ribs" where different colours cross.[7][23] Where a thread in the weft crosses threads of the same colour in the warp, this produces a solid colour on the tartan, while a weft thread crossing warp threads of a different colour produces an equal admixture of the two colours alternating, producing the appearance of a third colour – a halftone blend or mixture – when viewed from further back.[24][7][22] (The effect is similar to multicolour halftone printing, or cross-hatching in coloured-pencil art.)[7] Thus, a set of two base colours produces three different colours including one blend, increasing quadratically with the number of base colours; so a set of six base colours produces fifteen blends and a total of twenty-one different perceived colours.[7][25][d] This means that the more stripes and colours used, the more blurred and subdued the tartan's pattern becomes.[7][24] Unlike in simple checker (chequer) or dicing patterns (like a chessboard), no solid colour in a tartan appears next to another solid colour, only a blend[7] (solid colours may touch at their corners).[26]

James D. Scarlett (2008) offered a definition of a usual tartan pattern (some types of tartan deviate from the particulars of this definition):[7]

The unit of tartan pattern, the sett, is a square, composed of a number of rectangles, square and oblong, arranged symmetrically around a central square. Each of these elements occurs four times, at intervals of ninety degrees, and each is rotated ninety degrees in relation to its fellows. The proportions of the elements are determined by the relative widths of the stripes that form them.

The sequence of thread colours in the sett (the minimal design of the tartan, to be duplicated[7] – "the DNA of a tartan"),[27] starts at an edge and either reverses or (rarely) repeats on what are called pivot points or pivots.[28] In diagram A, the sett begins at the first pivot, reverses at the second pivot, continues, then reverses again at the next pivot, and will carry on in this manner horizontally. In diagram B, the sett proceeds in the same way as in the warp but vertically. The diagrams illustrate the construction of a typical symmetric[29] (also symmetrical,[27] reflective,[27] reversing,[30] or mirroring)[31][e] tartan. However, on a rare asymmetric[33] (asymmetrical,[27] or non-reversing)[33][f] tartan, the sett does not reverse at the pivots, it just repeats at them.[g] An old term for the latter type is cheek or cheeck pattern.[35] Also, some tartans (very few among traditional Scottish tartans) do not have exactly the same sett for the warp and weft. This means the warp and weft will have differing thread counts .[h] Asymmetric and differing-warp-and-weft patterns are more common in madras cloth and some other weaving traditions than in Scottish tartan.

-

Diagram A, the warp

-

Diagram B, the weft

-

Diagram C, the tartan. The combining of the warp and weft.

A tartan is recorded by counting the threads of each colour that appear in the sett.[i] The thread count (or threadcount, thread-count) not only describes the width of the stripes on a sett, but also the colours used (typically abbreviated).[27] Usually every number in a thread count is an even number[42] to assist in manufacture. The first and last threads of the thread count are the pivots.[28] A thread count combined with exact colour information and other weaving details is referred to as a ticket stamp[43] or simply ticket.[44]

There is no universally standardised way to write a thread count,[37] but the different systems are easy to distinguish. As a simple example:

- The thread count "/K4 R24 K24 Y4/" corresponds to a mirroring pattern of 4 black threads, 24 red threads, 24 black threads, 4 yellow threads, in which the beginning black and ending yellow pivots are not repeated (after Y4/, the colours are reversed, first K24 then R24); this is a "full-count at the pivots" thread count.[28]

- An equivalent notation is boldfacing the pivot abbreviations: K4 R24 K24 Y4.

- The same tartan could also be represented as "K/2 R24 K24 Y/2", in markup that indicates that the leading black and trailing yellow are duplicated before continuing from these pivot points (after Y/2, the colours are reversed as Y/2 again, then K24, then R24); this is a "half-count at the pivots" thread count.[27]

- In the older and potentially ambiguous style of thread-counting, without the "/" (or bold) notation, a thread count like "K4 R24 K24 Y4" is assumed to be full-count at the pivots, unless the author clearly indicates otherwise.[28][37][j]

In all of these cases, the result is a half-sett thread count, which represents the threading before the pattern mirrors and completes; a full-sett thread count for a mirroring (symmetric) tartan is redundant.[37] A "/" can also be used between two colour codes (e.g. "W/Y24" for "white/yellow 24") to create even more of a shorthand threadcount for simple tartans in which half of the half-sett pattern is different from the other only in the way of a colour swap;[45] but this is not a common style of thread-counting.

- An asymmetric tartan, one that does not mirror, would be represented in a full-sett thread count with "..." markup, as "...K4 R24 K24 Y4..." (after Y4, the entire pattern would begin again from K4).[27]

Various writers and tartan databases do not use a consistent set of colour names and abbreviations,[46] so a thread count may not be universally understandable without a colour key/legend. Some recorders prefer to begin a thread count at the pivot with the colour name (or abbreviation) that is first in alphabetical order (e.g. if there is a white pivot and a blue one, begin with blue),[27] but this is actually arbitrary.

Though thread counts are quite specific, they can be modified depending on the desired size of the tartan. For example, the sett of a tartan (e.g., 6 inches square – a typical size for kilts)[27] may be too large to fit upon the face of a necktie. In this case, the thread count would be reduced in proportion (e.g. to 3 inches to a side).[37] In some works, a thread count is reduced to the smallest even number of threads (often down to 2) required to accurately reproduce the design;[28] in such a case, it is often necessary to up-scale the thread count proportionally for typical use in kilts and plaids.

Before the 19th century, tartan was often woven with thread for the weft that was up to 1/3 thicker than the fine thread used for the warp,[7] which would result in a rectangular rather than square pattern; the solution was to adjust the weft thread count to return the pattern to square,[23] or make it non-square on purpose, as is still done in a handful of traditional tartans.[h] Uneven warp-and-weft thread thickness could also contribute to a striped rather than checked appearance in some tartan samples.[47]

The predominant colours of a tartan (the widest bands) are called the under-check (or under check, undercheck, under-cheque);[48] sometimes the terms ground,[k] background,[50] or base[50] are used instead, especially if there is only one dominant colour. Thin, contrasting lines are referred to as the over-check[51][50] (also over-stripe or overstripe).[52] Over-checks in pairs are sometimes referred to as tram lines, tramlines, or tram tracks.[53] Bright over-checks are sometimes bordered on either side (usually both), for extra contrast, by additional thin lines, often black, called guard lines or guards.[53] Historically, the weaver William Wilson & Son of Bannockburn sometimes wove bright over-checks in silk, to give some added shine[54][55] (commercially around 1820–30, but in regimental officers' plaids back to at least 1794).[56][l] Tartan used for plaids (not the belted plaid) often have a purled fringe.[57]

An old-time practice, to the 18th century, was to add an accent on plaids or sometimes kilts in the form of a selvedge in herringbone weave at the edge, 1–3 inches (2.5–7.6 cm) wide, but still fitting into the colour pattern of the sett;[57][58] a few modern weavers will still produce some tartan in this style. Sometimes more decorative selvedges were used: Selvedge marks were borders (usually on one side only) formed by repeating a colour from the sett in a broad band (often in herringbone), sometimes further bordered by a thin strip of another colour from the sett or decorated in mid-selvedge with two thin strips; these were typically used for the bottoms of belted plaids and kilts,[57][59] and were usually black in military tartans, but could be more colourful in civilian ones.[60] The more elaborate selvedge patterns were a wider series of narrow stripes using some or all of the colours of the sett; these were almost exclusively used on household tartans (blankets, curtains, etc.), and on two opposing sides of the fabric.[60][57] The very rare total border is an all-four-sides selvedge of a completely different sett; described by Peter Eslea MacDonald (2019) as "an extraordinarily difficult feature to weave and can be regarded as the zenith of the tartan weaver's art",[57] it only survives in Scottish-style tartan as a handful of 18th-century samples (in Scotland[61] and Nova Scotia, Canada, but probably all originally from Scotland).[62] The style has also been used in Estonia in the weaving of suurrätt shawls/plaids.

-

18th-century tartan with a herringbone selvedge at the bottom

-

Black Watch tartan with a selvedge mark at the bottom (also herringbone)

-

Wilsons 1819 blanket tartan with a selvedge pattern on the right

-

Bottom-right corner of blanket with total border selvedge; approximation based on photo of real blanket discovered in Nova Scotia, but probably Scottish, c. 1780s

Tartan is usually woven balanced-warp (or just balanced), repeating evenly from a pivot point at the centre outwards and with a complete sett finishing at the outer selvedge;[8][63][64] e.g. a piece of tartan for a plaid might be 24 setts long and 4 wide. An offset, off-set, or unbalanced weave is one in which the pattern finishes at the edge in the middle of a pivot colour; this was typically done with pieces intended to be joined (e.g. for a belted plaid or a blanket) to make larger spans of cloth with the pattern continuing across the seam;[8][64] if the tartan had a selvedge mark or selvedge pattern, it was at the other side of the warp.[65]

The term hard tartan refers to a version of the cloth woven with very tightly wound, non-fuzzy thread, producing a comparatively rougher and denser (though also thinner) material than is now typical for kilts.[66][67] It was in common use up until the 1830s.[47] There are extant but uncommon samples of hard tartan from the early 18th century that use the more intricate herringbone instead of twill weave throughout the entire cloth.[68]

While modern tartan is primarily a commercial enterprise on large power looms, tartan was originally the product of rural weavers of the pre-industrial age, and can be produced by a dedicated hobbyist with a strong, stable hand loom.[69][70][71] Since around 1808, the traditional size of the warp reed for tartan is 37 inches (94 cm), the length of the Scottish ell (previous sizes were sometimes 34 and 40 inches).[72] Telfer Dunbar (1979) describes the setup thus:[72]

The reed varies in thickness according to the texture of the material to be woven. A thirty-Porter (which contains 20 splits of the reed) or 600-reed, is divided into 600 openings in the breadth of 37 inches. Twenty of these openings are called a Porter and into each opening are put two threads, making 1,200 threads of warp and as many of weft in a square yard of tartan through a 30-Porter reed.

Splits are also referred to as dents, and Porters are also called gangs.[73]

Styles and design principles

[edit]Traditional tartan patterns can be divided into several style classes. The most basic is a simple two-colour check of thick bands (with or without thin over-checks of one or more other colours). A variant on this splits one or more of the bands, to form squares of smaller squares instead of just big, solid squares; a style heavily favoured in Vestiarium Scoticum. A complexity step up is the superimposed check, in which a third colour is placed centrally "on top of" or "inside" (surrounded by) one of the base under-check colours, providing a pattern of nested squares, which might then also have thin, bright and/or black over-checks added. Another group is multiple checks, typically of two broad bands of colour on a single dominant "background" (e.g. red, blue, red, green, red – again possibly with contrasting narrow over-checks). The aforementioned types can be combined into more complex tartans. In any of these styles, an over-check is sometimes not a new colour but one of the under-check colours "on top of" the other under-check. A rare style, traditionally used for arisaid (earasaid) tartans but no longer in much if any Scottish use, is a pattern consisting entirely of thin over-checks, sometimes grouped, "on" a single ground colour, usually white.[74] M. Martin (1703) reported that the line colours were typically blue, black, and red.[75] Examples of this style do not survive,[76] at least not in the tartan databases (there may be preserved museum pieces with such patterns).[m] Some tartan patterns are more abstract and do not fit into any of these styles,[78] especially in madras cloth .

-

Most basic check – MacGregor red-and-black (Rob Roy), as simple as it gets: equal proportions of two colours.

-

Basic check modified – Wallace red/dress, black on a slightly larger ground of red, laced with yellow and black over-checks.

-

Split check – MacGregor red-and-green with a wide green band split into three to form a "square of squares", then laced with a white over-check.

-

Superimposed check – Ruthven, a red ground with a big green stripe "inside" a bigger blue one, then white and green over-checks.

-

Multiple checks – Davidson, a green ground with equal blue and black bands, then with red, blue, and black over-checks.

-

Complex example – Ross, combines split-check and multiple-check styles, with one blue and two green split checks on red, with blue and green over-checks.

There are no codified rules or principles of tartan design, but a few writers have offered some considered opinions. Banks & de La Chapelle (2007) summarized, with a view to broad, general tartan use, including for fashion: "Color – and how it is worked – is pivotal to tartan design.... Thus, tartans should be composed of clear, bright colors, but ones sufficiently soft to blend well and thereby create new shades." James D. Scarlett (2008) noted: "the more colours to begin with, the more subdued the final effect",[50] or put more precisely, "the more stripes to the sett and the more colours used, the more diffuse and 'blurred' the pattern".[7] That does not necessarily translate into subtlety; a tartan of many colours and stripes can seem "busy".[79]

Scarlett (2008), after extensive research into historical Highland patterns (which were dominated by rich red and medium green in about equal weight with dark blue as a blending accent – not accounting for common black lines), suggested that for a balanced and traditional style:[7]

any basic tartan type of design should have for its background, a "high impact" colour and two others, of which one should be the complement to the first and the other a darker and more neutral shade; other colours, introduced to break up the pattern or as accents, should be a matter of taste. It is important that no colour should be so strong as to "swamp" another; otherwise, the blending of colours at the crossing will be adversely affected. ... Tartan is a complex abstract art-form with a strong mathematical undertone, far removed from a simple check with a few lines of contrasting colours scattered over it.

Scarlett (1990) provided a more general explanation, traditional styles aside:[80]

Colours for tartan work require to be clear and unambiguous and bright but soft, to give good contrast of both colour and brightness and to mix well so as to give distinctly new shades where two colours cross without any one swamping another.

Further, Scarlett (1990) held that "background checks will show a firm but not harsh contrast and the overchecks will be such as to show clearly" on the under-check (or "background") colours.[50] He summed up the desired total result as "a harmonious blend of colour and pattern worthy to be looked upon as an art form in its own right".[81]

Omitting traditional black lines has a strong softening effect, as in the 1970s Missoni fashion ensemble and in many madras patterns . A Scottish black-less design (now the Mar dress tartan) dates to the 18th century;[82] another is Ruthven (1842, ), and many of the Ross tartans (e.g. 1886, ), as well as several of the Victorian–Edwardian MacDougal[l] designs,[83] are further examples. Various modern tartans also use this effect, e.g. Canadian Maple Leaf (1964, ). Clever use of black or another dark colour can produce a visual perception of depth.[84]

Colour, palettes, and meaning

[edit]

There is no set of exact colour standards for tartan hues; thread colour varies from weaver to weaver even for "the same" colour.[85] A certain range of general colours, however, are traditional in Scottish tartan. These include blue (dark), crimson (rose or dark red), green (medium-dark), black, grey (medium-dark), purple, red (scarlet or bright), tan/brown, white (actually natural undyed wool, called lachdann in Gaelic),[86][n] and yellow.[45][7][o] Some additional colours that have been used more rarely are azure (light or sky blue), maroon, and vert (bright or grass green),[45] plus light grey (as seen in Balmoral tartan, though it is sometimes given as lavender).[89] Since the opening of the tartan databases to registration of newly designed tartans, including many for organisational and fashion purposes, a wider range of colours have been involved, such as orange[90] and pink,[91] which were not often used (as distinct colours rather than as renditions of red) in old traditional tartans.[p] The Scottish Register of Tartans uses a long list of colours keyed to hexadecimal "Web colours", sorting groups of hues into a constrained set of basic codes (but expanded upon the above traditional list, with additional options like dark orange, dark yellow, light purple, etc.).[92] This helps designers fit their creative tartan into a coding scheme while allowing weavers to produce an approximation of that design from readily stocked yarn supplies.

In the mid-19th century, the natural dyes that had been traditionally used in the Highlands[24][93][94][q] (like various lichens, alder bark, bilberry, cochineal, heather, indigo, woad, and yellow bedstraw) began to be replaced by artificial dyes, which were easier to use and were more economic for the booming tartan industry,[95] though also less subtle.[96] Although William Morris in the late-19th-century Arts and Crafts movement tried to revive use of British natural dyes, most were so low-yield and so inconsistent from locality to locality (part of the reason for the historical tartan differentiation by area) that they proved to have little mass-production potential, despite some purple dye (cudbear) commercialisation efforts in Glasgow in the 18th century.[95] The hard-wound, fine wool used in tartan weaving was rather resistant to natural dyes, and some dye baths required days or even weeks.[95] The dyeing also required mordants to fix the colours permanently, usually metallic salts like alum; there are records from 1491 of alum being imported to Leith, though not necessarily all for tartan production in particular.[97] Some colours of dye were usually imported, especially red cochineal and to some extent blue indigo (both expensive and used to deepen native dyes), from the Low Countries, with which Scotland had extensive trade since the 15th century.[98] Aged human urine (called fual or graith) was also used, as a colour-deepener, a dye solubility agent, a lichen fermenter, and a final colour-fastness treatment.[99] All commercially manufactured tartan today is coloured using artificial not natural dyes, even in the less saturated colour palettes.[100][101]

The hues of colours in any established tartan can be altered to produce variations of the same tartan. Such varying of the hues to taste dates to at least the 1788 pattern book of manufacturer William Wilson & Son of Bannockburn.[102] Today, the semi-standardised colour schemes or palettes (what marketers might call "colourways")[103] are divided generally into modern, ancient, muted, and weathered (sometimes with other names, depending on weaver). These terms only refer to relative dye "colourfulness" saturation levels and do not represent distinct tartans.[104][105]

- Modern

- Also known as ordinary; refers to darker tartan, with fully saturated colours.[101][105] In a modern palette, setts made up of blue, black, and green tend to be obscured because of the darkness of the colours in this scheme.[101]

- Ancient

- Also known as old colours (OC); refers to a lighter palette of tartan. These hues are ostensibly meant to represent the colours that would result from natural-dyed fabric aging over time. However, the results are not accurate (e.g., in real examples of very old tartan, black often fades toward khaki[101] or green[106] while blue remains dark;[101] and natural dyes are capable of producing some very vibrant colours in the first place, though not very consistently).[105][80][107] This style originated in the first half of the 20th century.[108][105] This ancient is not to be confused with the same word in a few names of tartans such as "ancient Campbell".

- Weathered

- Also called faded; refers to tartan that is even lighter (less saturated) than ancient, as if exposed for a very long time.[105] This style was invented in the late 1940s.[108]

- Muted

- Refers to tartan which is between modern and ancient in vibrancy. Although this type of colouring is very recent, dating only from the early 1970s, these hues are thought to be the closest match to the colours attained by natural dyes used before the mid-19th century.[105]

Some particular tartan mills have introduced other colour schemes that are unique to that weaver and only available in certain tartans. Two examples are Lochcarron's antique,[105] between modern and ancient; and D. C. Dalgliesh's reproduction, a slight variation on weathered,[104] dating to the 1940s and claimed to be based on 18th-century samples.[109]

A general observation about ancient/old, weathered/faded, and muted are that they rather uniformly reduce the saturation of all colours, while actual natural-dyed tartan samples show that the historical practice was usually to pair one or more saturated colours with one or more pale ones, for greater clarity and depth, a "harmonious balance".[110][105][104] According to Scarlett (1990): "The colours were clear, bright and soft, altogether unlike the eye-searing brilliance or washed-out dullness of modern tartans".[81]

The same tartan in the same palette from two manufacturers (e.g. Colquhoun muted from D. C. Dalgliesh and from Strathmore) will not precisely match; there is considerable artistic license involved in exactly how saturated to make a hue.[101]

Tartan-generation software can approximate the appearance of a tartan in any of these palettes. The examples below are all the "Prince Charles Edward Stuart" tartan:[111]

-

Modern palette

-

Ancient or old colours palette

-

Weathered or faded palette

-

Muted palette

-

Lochcarron-style antique palette

-

D. C. Dalgliesh-style reproduction palette

Scottish tartans that use two or more hues of the same basic colour are fairly rare. The best known is the British royal family's Balmoral[112] (1853, two greys, both as under-check). Others include: Akins[113] (1850, two reds, one as over-check and sometimes rendered purple), MacBean[114] (1872, two reds, one as over-check and sometimes rendered purple), Childers Universal regimental[115] (1907, two greens, both under-check), Gordon red[116] (recorded 1930–1950 but probably considerably older; two blues and two reds, one of each used more or less as over-checks), Galloway district hunting/green[117][118] (1939/1950s, two greens, both under-check), US Air Force Reserve Pipe Band[119] (1988, two blues, both under-check), McCandlish[120][121][122] (1992, three variants, all under-check), Isle of Skye district[123] (1992, three greens, all arguably under-check, nested within each other), and Chisholm Colonial[124] (2008, two blues, one an over-check, the other nearly blended into green). The practice is more common in very recent commercial tartans that have no association with Scottish families or districts, such as the Loverboy fashion label tartan[125] (2018, three blues, one an over-check).

The idea that the various colours used in tartan have a specific meaning is purely a modern one,[126] notwithstanding a legend that red tartans were "battle tartans", designed so they would not show blood. It is only recently created tartans, such as Canadian provincial and territorial tartans (beginning 1950s) and US state tartans (beginning 1980s), that are stated to be designed with certain symbolic meaning for the colours used. For example, green sometimes represents prairies or forests, blue can represent lakes and rivers, and yellow might stand for various crops.[127] In the Scottish Register of Tartans (and the databases before it), colour inspiration notes are often recorded by a tartan's designer. However, there is no common set of tartan colour or pattern "motifs" with allusive meanings that is shared among designers.[r]

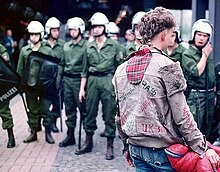

More abstractly, from an art criticism perspective, design historian Richard Martin (1988) wrote of tartans as designs and tartan as a textile class having no truly endemic or objectified meanings, but being an art that "has the property of being a vessel or container of meaning, a design form that exists not only in history but through history", capable of conveying radically different, even contradictory, contextual meanings "ever changing and evolving" through socio-cultural transmutation of the fabric's use. Thus tartan could veer from symbol of anti-union and Jacobite Highland rebellion to emblem of pan-British loyalty to empire in the space of two generations, or serve different fashion markets in the same recent decades as both a sartorial status symbol of traditional values and a punk and grunge rebel banner.[130]

Early history

[edit]Pre-medieval origins

[edit]Today, tartan is mostly associated with Scotland; however, the oldest tartan-patterned twill cloth[131] ever discovered dates to a heterogenous culture of the Tarim Basin, c. 2100 BC through the first centuries AD[131][132][133] in what today is Xinjiang, China, southeast of Kazakhstan. The tartan fabric (along with other types of simple and patterned cloth) was recovered, in excavations beginning in 1978, with other grave goods of the Tarim or Ürümqi mummies[134] – a group of often Caucasoid (light-haired, round-eyed)[135][136] bodies naturally preserved by the arid desert rather than intentionally mummified. The most publicised of them is the Chärchän Man, buried around 1,000 BC with tartan-like leggings in the Taklamakan Desert.[137][134] Other twill tartan samples (with differing warp and weft) were recovered in the region from the site of Qizilchoqa in 1979, dating to around 1,200 BC; the material was woven with up to six colours and required a sophisticated loom[131][138] (of a type that seems to have originated in the West).[134][s] Victor H. Mair, an archaeologist and linguist involved in the excavations wrote: "The ancient inhabitants ... undoubtedly had vibrant interactions with peoples of West Central Asia and even further west, since their magnificent textiles possess motifs, dyes, and weaves that are characteristic of cultures that lie in that direction."[131]

Textile analysis of that fabric has shown it to be similar to that of ancient Europe.[139] According to textile historian Elizabeth J. Wayland Barber, the late Bronze Age to early Iron Age people of Central Europe, the Hallstatt culture, which is linked with ancient Celtic populations and flourished between the 8th and 6th centuries BC, produced tartan-like textiles. Some of them were discovered in 2004, remarkably preserved, in the Hallstatt salt mines near Salzburg, Austria; they feature a mix of natural-coloured and dyed wool.[3][t] Some date back to 1,200 BC, and Wayland Barber says of them that: "The overall similarities between Hallstatt plaid twills and recent Scottish ones, right down to the typical weight of the cloth, strongly indicate continuity of tradition. The chief difference is that the Hallstatt plaids contain no more than two colors".[140] Similar finds have been made elsewhere in Central Europe and Scandinavia.[7]

Classical Roman writers made various references to the continental Gauls, south of Britain, wearing striped or variegated clothing; Latin seems to have lacked an exact word for 'checked'. For example, Virgil in the Aeneid (29–19 BC, book VIII, line 660) described the Gauls as virgatis lucent sagulis (or sagalis) meaning something like 'they shine in striped cloaks' or 'their cloaks are striped brightly'.[141][142][143] Other writers used words such as pictae and virgatae[144] with translations like 'marled', 'variegated', 'particoloured', etc. Scarlett (1990) warns: "What is not reasonable is the ready assumption by many modern authors that every time one of these words, or something like it, was used, tartan was intended."[145] It might have been intended sometimes, or the writer might have just meant linear stripes like seersucker cloth. Both Scarlett and Thompson (1992) decry the unsustainable assumption by a few earlier modern writers (e.g. James Grant, 1886) that Gauls must have been running around in clan tartans.[145][141] The Romans particularly wrote of Gauls as wearing striped braccae (trousers). E. G. Cody in remarks in his 1885 edition of John Lesley's Historie of Scotland hypothesized that this was actually a Gaulish loanword and was cognate with Gaelic breacan.[144] This is one of many "tartan legends" that is not well accepted; rather, braccae is considered by modern linguists a cognate of English breeches, Gaelic briogais ('trousers'), etc.[146]

The earliest documented tartan-like cloth in Britain, known as the "Falkirk tartan",[147] dates from the 3rd century AD.[148] It was uncovered at Falkirk in Stirlingshire, Scotland, near the Antonine Wall. The fragment, held in the National Museum of Scotland, was stuffed into the mouth of an earthenware pot containing almost 2,000 Roman coins.[149] The Falkirk tartan has a simple "Border check" design, of undyed light and dark wool.[u] Other evidence from this period is the surviving fragment of a statue of Roman Emperor Caracalla, once part of the triumphal arch of Volubilis completed in 217 AD. It depicts a Caledonian Pictish prisoner wearing tartan trews (represented by carving a checked design then inlaying it with bronze and silver alloys to give a variegated appearance).[150][v] Based on such evidence, tartan researcher James D. Scarlett (1990) believes Scottish tartan to be "of Pictish or earlier origin",[151] though Brown (2012) notes there is no way to prove or disprove this.[152]

Early forms of tartan like this are thought to have been invented in pre-Roman times, and would have been popular among the inhabitants of the northern Roman provinces[153][154] as well as in other parts of Northern Europe such as Jutland, where the same pattern was prevalent,[155][156][157] and Bronze Age Sweden.[158]

That twill weave was selected, even in ancient times, is probably no accident; "plain (2/2) twill for a given gauge of yarn, yields a cloth 50% heavier [denser] – and hence more weather-proof – than the simple 1/1 weave."[7] According to Scarlett (2008):[7]

[T]here are sound reasons why such a type of pattern-textile should have developed almost automatically in isolated, self-sufficient ... communities. Such communities are unlikely to possess large dye-vats, and so cannot piece-dye woven cloth; such processes as batik and tie-dye are unavailable. ... Stripes are the practical solution, since they use small quantities of a colour at a time and are interspersed with other colours, but the scope is limited ...; stripes across both brighten the colours and add many mixtures. From there on it is really only a matter of getting organised; the now-geometric pattern reduces to a small unit, easier to remember and to follow in a world where little was written down; it is further simplified by being split into two equal halves and, with weft as warp, the weft pattern can be followed from the warp.

Medieval

[edit]

There is little written or pictorial evidence about tartan (much less surviving tartan cloth) from the Medieval era. Tartan use in Britain between the 3rd-century Falkirk tartan and 16th-century samples, writings, and art is unclear.[159][160] Cosmo Innes (1860) wrote that, according to medieval hagiographies, Scots of the 7th–8th centuries "used cloaks of variegated colour, apparently of home manufacture".[161] Based on similarities of tartans used by various clans, including the Murrays, Sutherlands, and Gordons, and the history of their family interactions over the centuries, Thomas Innes of Learney estimated that a regional "parent" pattern, of a more general style, might date to the 12th or 13th century,[162] but this is quite speculative. The cartularies of Aberdeen in the 13th century barred clergymen from wearing "striped" clothing, which could have referred to tartan.[163]

In 1333, Italian Gothic artists Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi produced the Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus, a wood-panel painting in tempera and gold leaf. It features the archangel Gabriel in a tartan-patterned mantle, with light highlights where the darker stripes meet, perhaps representing jewels, embroidery, or supplementary weaving. Art historians consider it an example of "Tartar" (Mongol) textile influence; it likely has no relation to Scottish tartan.[w] "Tartar" cloth came in a great array of patterns, many more complex than tartan (such as the fine detail in Gabriel's robe in the same painting); patterns of this sort were influential especially on Italian art in the 14th century.

There are several other continental European paintings of tartan-like garments from around this era (even back to the 13th century), but most of them show very simple two-colour basic check patterns, or (like the Martini and Memmi Annunciation example) broad squares made by thin lines of one colour on a background of another. Any of them could represent embroidery or patchwork rather than woven tartan. There seems to be no indication in surviving records of tartan material being imported from Scotland in this period. In the second half of the 14th century, the artist known only as the "Master of Estamariu" (in Catalonia, Spain) painted an altarpiece of St Vincent, one of the details of which is a man in a cotehardie that is red on one half and a complex three-colour tartan on the other, which is very similar to later-attested Scottish tartans.

Sir Francis James Grant, mid-20th-century Lord Lyon King of Arms, noted that records showed the wearing of tartan in Scotland to date as far back as 1440.[164] However, it is unclear to which records he was referring, and other, later researchers have not matched this early date.

16th century

[edit]

The oldest surviving sample of complex, dyed-wool tartan (not just a simple check pattern) in Scotland has been shown through radiocarbon dating to be from the 16th century; known as the "Glen Affric tartan", it was discovered in the early 1980s in a peat bog near Glen Affric in the Scottish Highlands; its faded colours include green, brown, red, and yellow. On loan from the Scottish Tartans Authority, the 55 cm × 42 cm (22 in × 17 in) artefact went on display at the V&A Dundee museum in April 2023.[148][165][166][167][x]

The earliest certain written reference to tartan by name is in the 1532–33 accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland: "Ane uthir tartane galcoit gevin to the king be the Maister Forbes" ('Another tartan coat given to the king by the Master Forbes'),[5] followed not long after by a 1538 Scottish Exchequer accounting of clothing to be ordered for King James V of Scotland, which referred to "heland tertane to be hoiss" ('Highland tartan to be hose').[168][169][y] Plaids were featured a bit earlier; poet William Dunbar (c. 1459 – c. 1530) mentions "Five thousand ellis ... Of Hieland pladdis".[170] The earliest surviving image of a Highlander in what was probably meant to represent tartan is a 1567–80 watercolour by Lucas de Heere, showing a man in a belted, pleated yellow tunic with a thin-lined checked pattern, a light-red cloak, and tight blue shorts (of a type also seen in period Irish art), with claymore and dirk.[171] It looks much like medieval illustrations of "Tartar" cloth and thus cannot be certain to represent true tartan. By the late 16th century, there are numerous references to striped or checked plaids. Supposedly, the earliest pattern that is still produced today (though not in continual use) is the Lennox district tartan,[172] (also adopted as the clan tartan of Lennox)[173] said to have been reproduced by D. W. Stewart in 1893 from a portrait of Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox, dating to around 1575.[174] However, this seems to be legend, as no modern tartan researchers or art historians have identified such a portrait, and the earliest known realistic one of a woman in tartan dates much later, to c. 1700.[175] Extant portraits of Margaret show her in velvet and brocade.[176]

Tartan and Highland dress in the Elizabethan era have been said to have become essentially classless[z] – worn in the Highlands by everyone from high-born lairds to common crofters,[182] at least by the late 16th century. The historian John Major wrote in 1521 that it was the upper class, including warriors, who wore plaids while the common among them wore linen, suggesting that woollen cloth was something of a luxury.[183] But by 1578, Bishop John Lesley of Ross wrote that the belted plaid was the general Highland costume of both rich and poor, with the nobility simply able to afford larger plaids with more colours.[180] (Later, Burt (1726) also wrote of gentlemen having larger plaids than commoners.)[20] If colours conveyed distinction, it was of social class not clan.[184] D. W. Stewart (1893) attributed the change, away from linen, to broader manufacture of woollen cloth and "the increased prosperity of the people".[180]

Many writers of the period drew parallels between Irish and Highland dress, especially the wearing of a long yellow-dyed shirt called the léine or saffron shirt (though probably not actually dyed with expensive imported saffron),[185] worn with a mantle (cloak) over it, and sometimes with trews.[186] It is not entirely certain when these mantles were first made of tartan in the Highlands, but the distinctive cloth seems to get its recorded mentions first in the 16th century, starting with Major (1521). In 1556, Jean de Beaugué, a French witness of Scottish troops on the continent at the 1548 Siege of Haddington, distinguished Lowlanders from Highland "savages", and wrote of the latter as wearing shirts "and a certain light covering made of wool of various colours".[187][188] George Buchanan in 1582 wrote that "plaids of many colours" had a long tradition but that the Highland fashion by his era had mostly shifted to a plainer look, especially brown tones, as a practical matter of camouflage.[189][aa] Fynes Moryson wrote in 1598 (published 1617) of common Highland women wearing "plodan", "a course stuffe, of two or three colours in Checker worke".[192]

Its dense weave requiring specialised skills and equipment, tartan was not generally one individual's work but something of an early cottage industry in the Highlands – an often communal activity called calanas, including some associated folk singing traditions – with several related occupational specialties (wool comber, dyer, waulker, warp-winder, weaver) among people in a village, part-time or full-time,[194] especially women.[195][ac] The spinning wheel was a late technological arrival in the Highlands, and tartan in this era was woven from fine (but fairly inconsistent) hard-spun yarn that was spun by hand on drop spindles.[7] The era's commerce in tartans was centred on Inverness, the early business records of which are filled with many references to tartan goods.[198] Tartan patterns were loosely associated with the weavers of particular areas, owing in part to differences in availability of natural dyes,[95][199][93][200] and it was common for Highlanders to wear whatever was available to them,[1] often a number of different tartans at the same time.[201][ad] The early tartans found in east-coastal Scotland used red more often, probably because of easier continental-European trade in the red dye cochineal, while western tartans were more often in blues and greens, owing to the locally available dyes.[174] The greater expense of red dye may have also made it a status symbol.[203] Tartan spread at least somewhat out of the Highlands, but was not universally well received. The General Assembly of the Kirk of Scotland in 1575 prohibited the ministers and readers of the church (and their wives) from wearing tartan plaids and other "sumptuous" clothing,[204][205] while the council of Aberdeen, "a district by no means Highland", in 1576 banned the wearing of plaids (probably meaning belted plaids).[206]

A 1594 Irish account by Lughaidh Ó Cléirigh of Scottish gallowglass mercenaries in Ireland clearly describes the belted plaid, "a mottled garment with numerous colours hanging in folds to the calf of the leg, with a girdle round the loins over the garment".[207] The privately organised early "plantations" (colonies) and later governmental Plantation of Ulster brought tartan weaving to Northern Ireland in the late 16th to early 17th centuries.[208] Many of the new settlers were Scots, and they joined the population already well-established there by centuries of gallowglass and other immigrants. In 1956, the earliest surviving piece of Irish tartan cloth was discovered in peaty loam just outside Dungiven in Northern Ireland, in the form of tartan trews, along with other non-tartan clothing items.[209] It was dubbed the "Dungiven tartan" or "Ulster tartan".[210] The sample was dated using palynology to c. 1590–1650[211][212] (the soil that surrounded the cloth was saturated with pollen from Scots pine, a species imported to Ulster from Scotland by plantationers).[213][19] According to archaeological textile expert Audrey Henshall, the cloth was probably woven in County Donegal, Ireland, but the trews tailored in the Scottish Highlands[213][214] at some expense, suggesting someone of rank,[215] possibly a gallowglass.[211] Henshall reproduced the tartan for a 1958 exhibit;[213][19] it became popular (and heavily promoted) as a district tartan for Ulster[19] (both in a faded form, like it was found,[216] and a bright palette that attempted to reproduce what it may have originally looked like),[217] and seems to have inspired the later creation of more Irish district tartans.[19][218] . There is nearly nothing in period source material to suggest that the Irish also habitually wore tartan; one of the only sources that can possibly be interpreted in support of the idea is William Camden, who wrote in his Britannia (since at least the 1607 edition) that "Highlandmen ... wear after the Irish fashion striped mantles".[219][220][ae]

17th century

[edit]

The earliest unambiguous surviving image of Highlanders in an approximation of tartan is a watercolour, dating to c. 1603–1616 and rediscovered in the late 20th century, by Hieronymus Tielsch or Tielssch. It shows a man's belted plaid, and a woman's plaid (arisaid, earasaid) worn as a shawl or cloak over a dress, and also depicts diced short hose and a blue bonnet.[193][221][ab] Clans had for a long time independently raised militias, and starting in 1603, the British government itself mustered irregular militia units in the Highlands, known as the Independent Highland Companies (IHCs).[222] Being Highlanders, they were probably wearing tartan (1631 Highland mercenaries certainly were, and the ICHs were in tartan in 1709[222] and actual uniforms of tartan by 1725).[223][224][225] Tartan was used as a furnishing fabric, including bed hangings at Ardstinchar Castle in 1605.[226] After mention of Highlanders' "striped mantles" in Camden's Britannia of 1607,[219] poet John Taylor wrote in 1618 in The Pennyless Pilgrimage of "tartane" Highland garb in detail (in terms that generally match what was described and illustrated even two centuries later); he noted that it was worn not just by locals but also by visiting British gentlemen.[af][ag] The council of Aberdeen again cracked down on plaids in 1621, this time against their use as women's head-wear,[206] and the kirk in Glasgow had previously, in 1604, forbidden their wear during services;[228] similar kirk session rulings appeared in Elgin in 1624, in Kinghorn in 1642 and 1644, and Monifieth in 1643, with women's plaids more literarily censured in Edinburgh in 1633 by William Lithgow.[229] In 1622, the Baron Courts of Breadalbane set fixed prices for different complexities of tartan and plain cloth.[230]

In 1627, a tartan-dressed body of Highland archers served under the Earl of Morton.[231] More independent companies were raised in 1667.[222] The earliest image of Scottish soldiers in tartan is a 1631 copperplate engraving by Georg Köler (1600–1638); it features Highland mercenaries of the Thirty Years' War in the forces of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden.[232][233] Not long after, James Gordon, Parson of Rothiemay, wrote in A History of Scots Affairs from 1637 to 1641 of the belted plaid as "a loose Cloke of several Ells, striped and party colour'd, which they gird breadthwise with a Leathern Belt ...." He also described the short hose and trews ("trowzes").[234] A 1653 map, Scotia Antiqua by Joan Blaeu, features a cartouche that depicts men in trews and belted plaid; the tartan is crudely represented as just thin lines on a plain background,[235] and various existing copies are hand-coloured differently. Daniel Defoe, in Memoirs of a Cavalier (c. 1720) wrote, using materials that probably dated to the English Civil War, of Highlanders invading Northern England back in 1639 that they had worn "doublet, breeches and stockings, of a stuff they called plaid, striped across red and yellow, with short cloaks of the same".[236]

Besides the formerly often-chastised wearing of head-plaids in church, women's dress was not often described (except in earlier times as being similar to men's).[ah] The Highland and island women's equivalent of the belted plaid was the arisaid (earasaid), a plaid that could be worn as a large shawl or be wrapped into a dress. Sir William Brereton had written in 1634–35 (published 1844) of Lowland women in Edinburgh that: "Many wear (especially of the meaner sort) plaids ... which is [sic] cast over their heads and covers their faces on both sides, and would reach almost to the ground, but that they pluck them up, and wear them cast under their arms." He also reported that women there wore "six or seven several habits and fashions, some for distinction of widows, wives and maids", including gowns, capes/cloaks, bonnets with bongrace veils, and collar ruffs, though he did not address tartan patterns in particular in such garments.[238]

While tartan was still made in the Highlands as cottage industry, by 1655 production had centred on Aberdeen, made there "in greater plenty than [in] any other place of the nation whatsoever",[21] though it was also manufactured in Glasgow, Montrose, and Dundee, much of it for export.[21] In Glasgow at least, some of the trade was in tartan manufactured in the Highlands and the Hebrides and brought there for sale along with hides and other goods.[21] Impressed by the trade in Glasgow, Richard Franck in his Northern Memoirs of 1658 wrote that the cloth was "the staple of this country".[239] In 1662, the naturalist John Ray wrote of the "party coloured blanket which [Scots] call a plad, over their heads and shoulders", and commented that a Scotsman even of the lower class was "clad like a gentleman" because the habit in this time was to spend extraordinarily on clothing,[240] a habit that seems to have gone back to the late 16th century.[241] A Thomas Kirk of Yorkshire commented on trews, plaids, and possibly kilts of "plaid colour" in 1677;[242] more material by Kirk was printed in the 1891 Early Travellers in Scotland edited by Peter Hume Brown, recording "plad wear" in the form of belted plaids, trews, and hose.[243] A poem by William Cleland in 1678 had Scottish officers in trews and shoulder plaids, and soldiers in belted plaids.[244] In 1689, Thomas Morer, an English clergyman to Scottish regiments, described Lowland women as frequently wearing plaids despite otherwise dressing mostly like the English.[245]

The earliest known realistic portrait in tartan Highland dress is a piece (which exists in three versions) by John Michael Wright, showing a very complicated tartan of brown, black, and two hues of red;[246] it is dated to c. 1683 and is of Mungo Murray, son of John Murray, Marquess of Atholl.[247][ai]

In 1688, William Sacheverell, lieutenant governor of the Isle of Man, wrote of the tartan plaids of the women of Mull in the Inner Hebrides as "much finer, the colours more lively, and the squares larger than the men's .... This serves them for a veil, and covers both head and body."[249] In the 1691 poem The Grameid,[250] James Philip of Almerieclose described the 1689 Battle of Killiecrankie in terms that seem to suggest that some clan militias had uniform tartan liveries, and some historians have interpreted it thus.[251][252]

18th century

[edit]It is not until the early 18th century that regional uniformity in tartan, sufficient to identify the area of origin, is reported to have occurred.[159] Martin Martin, in A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland, published in 1703, wrote, after describing trews and belted plaids "of divers Colours ... agreeable to the nicest Fancy", that tartans could be used to distinguish the inhabitants of different places.[aj] Martin did not mention anything like the use of a special pattern by each family.

In 1709, the Independent Highland Companies were wearing everyday Highland dress, not uniforms of a particular tartan, to better blend in with civilians and detect Jacobite treachery.[222] In 1713, the Royal Company of Archers (a royal bodyguard unit first formed in 1676),[255] became the first unit in service to the British crown who adopted a particular tartan as a part of their formal uniform. The militiamen of Clan Grant may have been all in green-and-red tartan (details unspecified) as early as 1703–04[256][174] and wearing a uniform tartan livery by 1715.[257] It is not a surviving pattern, and modern Grant tartans are of much later date.[258]

An account of the Highland men in 1711 had it that they all, including "those of the better sort", wore the belted plaid.[259] A 1723 account suggested that gentlemen, at least when commingling with the English, were more likely to wear tartan trews and hose with their attendants in the belted plaid,[259] which Burt also observed;[260] trews were also more practical for horseback riding.[261] Also around 1723, short tartan jackets, called in Gaelic còta-goirid, sometimes with slashed sleeves and worn with a matching waistcoat, made their first appearance and began supplanting, in Highland dress, the plain-coloured doublets that were common throughout European dress of the era; the còta-goirid was often worn with matching trews and a shoulder plaid that might or might not match, but could also be worn with a belted plaid.[262][ak]

M. Martin (1703) wrote that the "vulgar" Hebridean women still wore the arisaid wrap/dress,[263] describing it as "a white Plad, having a few small Stripes of black, blue, and red; it reach'd from the Neck to the Heels, and was tied before on the Breast with a Buckle of Silver, or Brass", some very ornate. He said they also wore a decorated belt, scarlet sleeves, and head kerchiefs of linen.[264] Martin was not the only period source to suggest it was primarily the wear of the common women, with upper-class Highland ladies in the 18th century more likely to weartailored gowns, dresses, and riding habits, often of imported material, as did Lowland and English women.[175][265] Highland women's dress was also sometimes simply in linear stripes rather than tartan, a cloth called iomairt (drugget).[175] From the late 18th century, as the arisaid was increasingly set aside for contemporary womenswear, while Highland men continued wearing the belted plaid.,[266] the ladies' plaids were reduced to smaller "screens" – fringed shawls used as headdresses and as dress accessories,[265] "a gentrification of the arisaid".[175] (Wilsons continued producing these in the first half of the 19th century.)[175] John Macky in A Journey Through Scotland (1723) wrote of Scottish women wearing, when about, such tartan plaids over their heads and bodies, over English-style dress, and likened the practice to continental women wearing black wraps for church, market, and other functions.[245] Edmund Burt, an Englishman who spent years in and around Inverness, wrote in 1727–1737 (published 1754) that the women there also wore such plaids, made of fine worsted wool or even of silk, that they were sometimes used to cover the head, and that they were worn long, to the ankle, on one side. He added that in Edinburgh (far to the southeast) they were also worn, with ladies indicating their Whig or Tory political stance by which side they wore long (though he did not remember which side was which).[267] In Edinburgh, perennial disapproval of the "barbarous habitte" of women wearing plaids over their heads returned in 1753 writings of William Maitland. Women first appear in known painted portraits with tartan c. 1700, with that of Rachel Gordon of Abergeldie; more early examples are found in 1742 and 1749 paintings by William Mosman,. They show plaids (in tartans that do not survive as modern patterns) worn loosely around the shoulders by sitters in typical European-fashion dresses.[268] Some entire dresses of tartan feature in mid-18th-century portraits, but they are uncommon.[175] In the Jacobite period, tartan was sometimes also used as trim, e.g. on hats. Plaids were worn also as part of wedding outfits. The monied sometimes had entire wedding dresses of tartan, some in silk, and even devised custom tartans for weddings, typically based on existing patterns with colours changed.[265]

Portraits became more popular among the Highland elite starting in the early 18th century.[270] Similar cloth to that in the c. 1683 Mungo Murray portrait appears in the 1708 portrait of the young John Campbell of Glenorchy, attributed to Charles Jervas; and the c. 1712 portrait of Kenneth Sutherland, Lord Duffus, by Richard Waitt.[271] This style of very "busy" but brown-dominated tartan seems to have been fairly common through the early 18th century, and is quite different from later patterns.[272] As the century wore on, bolder setts came to dominate, judging from later portraits and surviving cloth and clothing samples. By the early 18th century, tartan manufacture (and weaving in general) were centred in Bannockburn, Stirling; this is where the eventually dominant tartan weaver William Wilson and Son, founded c. 1765, were based.[273][am]

Judging from rare surviving samples, the predominant civilian tartan colours of this period, in addition to white (undyed wool) and black, were rich reds and greens and rather dark blues, not consistent from area to area; where a good black was available, dark blue was less used.[7] The sett of a typical Highland pattern of the era as shown in portraits was red with broad bands of green and/or blue, sometimes with fine-line over-checks.[7][an] Oil portraiture was the province of the privileged, and "Sunday best" tartans with red grounds were commonly worn in them as a status symbol, from the early 18th century, the dye typically being made from expensive imported cochineal.[175][275] Green and blue more generally predominated owing to their relative ease of production with locally available dyes, with more difficult yellow[ao] and red dyes commonly being saved for thin over-check lines[277] (a practice that continued, e.g. in military and consequently many clan tartans, through to the 19th century). However, even local-dyestuff blues were often over-dyed with some amount of imported indigo for a richer colour.[49]

Union protest and Jacobite rebellion

[edit]The Treaty and Acts of Union in 1706–07, which did away with the separate Parliament of Scotland, led to Scottish Lowlanders adopting tartan in large numbers for the first time, as a symbol of protest against the union.[278][279] It was worn not just by men (regardless of social class),[280] but even influential Edinburgh ladies,[278][281] well into the 1790s.[282] By the beginning of the 18th century, there was also some demand for tartan in England, to be used for curtains, bedding, nightgowns, etc., and weavers in Norwich, Norfolk, and some other English cities were attempting to duplicate Scottish product, but were considered the lower-quality option.[259]

The most effective fighters for Jacobitism were the supporting Scottish clans, leading to an association of tartan and Highland dress with the Jacobite cause to restore the Catholic Stuart dynasty to the throne of England, Scotland, and Ireland. This included great kilts, and trews (trousers) with great coats, all typically of tartan cloth, as well as the blue bonnet. The British parliament had considered banning the belted plaid after the Jacobite rising of 1715, but did not.[283] Highland garb came to form something of a Jacobite uniform,[282][284] even worn by Prince Charles Edward Stuart ("Bonnie Prince Charlie") himself by the mid-18th century,[285][ap] mostly in propaganda portraits (with inconsistent tartans) but also by eyewitness account at Culloden.[291] By this period, sometimes a belted plaid was worn over tartan trews and jacket (in patterns that need not match).[292]

Burt had concurred c. 1728, as did his 1818 editor Robert Jamieson, with Buchanan's much earlier 1582 observation that tartans were often in colours intended to blend into heather and other natural surroundings.[293] This may just represent prejudices of English writers of the period, however, at least by the mid-18th century. Extant samples of Culloden-era cloth are sometimes quite colourful. One example is a pattern found on a coat (probably Jacobite) known to date to around the 1745 uprising; while it has faded to olive and navy tones, the sett is a bold one of green, blue, black, red, yellow, white, and light blue (in diminishing proportions). While an approximation of the pattern was first published in D. W. Stewart (1893), the colours and proportions were wrong; the original coat was rediscovered and re-examined in 2007.[294][295] Another surviving Culloden sample, predominantly red with broad bands of blue, green, and black, and some thin over-check lines, consists of a largely intact entire plaid that belonged on one John Moir; it was donated to the National Museum of Scotland in 2019.[296]

There is a legend that a particular still-extant tartan was used by the Jacobites as an identifier even prior to "the '15". This story can be traced to W. & A. Smith (1850) in Authenticated Tartans of the Clans and Families of Scotland, in which they claimed that a pattern they published was received from an unnamed woman then still living who in turn claimed a family tradition that the tartan dated to 1712, long before her birth, but for which there is no evidence.[32] This hearsay tale was later repeated as if known fact by other books, e.g., Adam Frank's What Is My Tartan? in 1896,[297] and Margaret MacDougall's 1974 revision of Robert Bain's 1938 Clans and Tartans of Scotland.[aq] Even the often credulous Innes of Learney (1938) did not believe it.[300] The pattern in question does date to at least c. 1815–26, because it was collected by the Highland Society of London during that span.[32] But there is no substantiated evidence of Jacobites using a consistent tartan, much less one surviving to the present.

Independent Highland Companies were re-raised from Scottish clans loyal to the Hanoverian monarchy during 1725–29.[301][ar][302] This time they wore uniform tartans of blue, black, and green, presumably with differencing over-check lines.[303][302][223] They were all normalised to one tartan during 1725–33[223][225][224][304] (a pattern which probably does not survive to the present day).[174] The uniform tartan appears to have changed into a new tartan, known today as Black Watch or Government, when the companies amalgamated to become the 42nd (Black Watch) regiment in 1739.

Proscription and its aftermath

[edit]After the failure of the Jacobite rising of 1745, efforts to pacify the Highlands and weaken the cultural and political power of the clans[305][306] led to the Dress Act 1746, part of the Act of Proscription to disarm the Highlanders. Because tartan Highland dress was so strongly symbolically linked to the militant Jacobite cause,[307] the act – a highly political throwback to the long-abandoned sumptuary laws[307] – banned the wearing of Highland dress by men and boys in Scotland north of the River Forth (i.e. in the Highlands),[as] except for the landed gentry[at] and the Highland regiments of the British Army.[309] The law was based on 16th century bans against the wearing of traditional Irish clothing in the Kingdom of Ireland by the Dublin Castle administration.[310] Sir Walter Scott wrote of the Dress Act: "There was knowledge of mankind in the prohibition, since it divested the Highlanders of a dress which was closely in association with their habits of Clanship and of war."[311]

Tartans recorded shortly after the act (thus probably being patterns in use in the period before proscription) show that a general pattern was used in a wide area, with minor changes being made by individual weavers to taste.[232] E.g., the tartan today used as the main (red) Mackintosh clan tartan,[312] recorded by the Highland Society of London around 1815, was found in variants from Perthshire and Badenoch along the Great Glen to Loch Moy.[232] Other such groups can be found, e.g. a Huntly-centred Murray/Sutherland/Gordon cluster analysed as clearly related by Innes of Learney (1938)[162] – distinguished from a different Huntly/MacRae/Ross/Grant group identified by Scottish Register of Tartans and tartan researcher Peter Eslea MacDonald of Scottish Tartans Authority.[313][314] But Scarlett (1990) says that "the old patterns available are too few in number to permit a detailed study of such pattern distributions" throughout the Highlands.[232] Portraits of the era also show that tartan was increasingly made with identical or near-identical warp and weft patterns, which had not always been the case earlier, and that the tartan cloth used was of the fine twill, with even-warp-and-weft thickness, still used today for kilts.[252][270]

Although the Dress Act, contrary to popular later belief, did not ban all tartan[315] (or bagpipes, or Gaelic), and women, noblemen, and soldiers continued to wear tartan,[316] it nevertheless effectively severed the everyday tradition of Highlanders wearing primarily tartan, as it imposed the wearing of non-Highland clothing common in the rest of Europe for two generations.[309][317] (While some Highlanders defied the act,[318][319] there were stiff criminal penalties.)[320] It had a demoralising effect,[au] and the goal of this and related measures to integrate the Highlanders into Lowland and broader British society[310] was largely successful.[307][322] By the 1770s, Highland dress seemed all but extinct.[323] However, the act may also ironically have helped to "galvanize clan consciousness" under that suppression;[324] Scottish clans, in romanticised form, were to come roaring back in the "clan tartans" run of the Regency (late Georgian) to Victorian period.

In the interim, Jacobite women continued using tartan profusely, for clothing (from dresses to shoes), curtains, and everyday items.[326][316] While Classicism-infused portraiture of 18th-century clan nobles (often painted outside Scotland) typically showed them in tartan and "Highland" dress, much of it was loyalist regimental military stylings, the antithesis of Jacobite messaging;[327] it foreshadowed a major shift in the politics of tartan . Nevertheless, this profuse application of tartan could be seen as rebellious to some extent, with the reified Highlander becoming "a heroic and classical figure, the legatee of primitive virtues."[328] And by the 1760s, tartan had become increasingly associated with Scotland in general, not just the Highlands, especially in the English mind.[329]

After much outcry (as the ban applied to Jacobites and loyalists alike), the Dress Act was repealed in 1782, primarily through efforts of the Highland Society of London;[331] the repeal bill was introduced by James Graham, Marquis of Graham (later Duke of Montrose).[332] Some Highlanders resumed their traditional dress,[333] but overall it had been abandoned by its former peasant wearers, taken up instead by the upper and middle classes, as a fashion.[334] Tartan had been "culturally relocated as a picturesque ensemble or as the clothing of a hardy and effective fighting force" for the crown, not a symbol of direct rebellion.[335] R. Martin (1988) calls this transmutation "the great bifurcation in tartan dress",[336] the cloth being largely (forcibly) abandoned by the original Highland provincials then taken up by the military and consequently by non-Highlander civilians. During the prohibition, traditional Highland techniques of wool spinning and dyeing, and the weaving of tartan, had sharply declined.[95][308][104] Commercial production of tartan was to become re-centred in the Lowlands, in factory villages along the fringe of the Highlands,[337] among companies like Wilsons of Bannockburn (then the dominant manufacturer),[338] with the rise of demand for tartan for military regimental dress.[339] Some tartan weaving continued in the Highlands,[340][341] and would even see a boost in the late Georgian period.[340] Tartan by this era had also become popular in Lowland areas including Fife and Lothian and the urban centres of Edinburgh and Stirling.[315] From 1797 to 1830,[273] Wilsons were exporting large quantities of tartan (for both men's and women's clothing), first to the British colonies in Grenada and Jamaica (where the affordable, durable, and bright material was popular for clothing enslaved people),[337] and had clients in England, Northern and Central Europe, and a bit later in North and South America and the Mediterranean.[342][343] However, by the end of the 18th century, Wilsons had "stiff competition" (in civilian tartan) from English weavers in Norwich.[344]

Because the Dress Act had not applied to the military or gentry, tartan gradually had become associated with the affluent, rather than "noble savage" Highlanders,[345][346][347] from the late 18th century and into the 19th,[348] along with patriotic military-influenced clothing styles in general;[349] tartan and militarised Highland dress were being revived among the fashion-conscious across Britain, even among women with military relatives.[350] The clans, Jacobitism, and anti-unionism (none of them any longer an actual threat of civil unrest) were increasingly viewed with a sense of nostalgia,[182][351][352][347] especially after the death of Prince Charles Edward Stuart in 1788,[353] even as Highland regiments proved their loyalty and worth.[347] Adopting the airs of a Tory sort of tartaned "Highlandism"[354] provided a post-union and resigned sense of national (and militarily elite) distinction from the rest of Britain, without threatening empire.[355] Even the future George IV donned Highland regalia for a masquerade ball in 1789.[356] By the 1790s, some of the gentry were helping design tartans for their own personal use, according to surviving records from Wilsons.[182] Jane (Maxwell) Gordon, Duchess of Gordon, was said to have "introduced tartan to [royal] court ... wearing a plaid of the Black Watch, to which her son had just been appointed", in 1792; she triggered a fashion of wearing tartan in London and Paris, though was not immune to caricature by the disapproving.[357]

R. Martin (1988) wrote, from a historiographical perspective, that after the Dress Act:[336]

the idea of Highland dress was stored in the collective historical attic; when it was revived in the years leading up to 1822, it had been forgotten by some two or three generations in civilian dress and could be remembered, however deceptively, however naively, to have been the ancient dress of the Highlands, not that so recently worn as the standard peasant dress before 1746. The ban on tartan was hugely successful, but so inimical to a natural historical process, that it promoted the violent re-assertion of the tartan, sanctioned by a spurious sense of history, in the next century.

The tumultuous events of 18th-century Scotland led to not just broader public use of tartan cloth, but two particular enduring tartan categories: regimental tartans and eventually clan tartans.

Regimental tartans

[edit]

After the period of the early clan militias and the Independent Highland Companies (IHCs), over 100 battalions of line, fencible, militia, and volunteer regiments were raised, between c. 1739 and the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, in or predominantly in the Highlands,[358] a substantial proportion of them in Highland dress. Of these units, only some had distinct uniform tartans, and of those, only a small number were recorded to the present day.