Settler colonialism

Settler colonialism is a logic and structure of displacement by settlers, using colonial rule, over an environment for replacing it and its indigenous peoples with settlements and the society of the settlers.[1][2][3][4]

Settler colonialism is a form of exogenous (of external origin, coming from the outside) domination typically organized or supported by an imperial authority, which maintains a connection or control to the territory through the settler's colonialism.[5] Settler colonialism contrasts with exploitation colonialism, where the imperial power conquers territory to exploit the natural resources and gain a source of cheap or free labor. As settler colonialism entails the creation of a new society on the conquered territory, it lasts indefinitely unless decolonisation occurs through departure of the settler population or through reforms to colonial structures, settler-indigenous compacts and reconciliation processes.[a][6]

Settler colonial studies has often focused on former British colonies in North America, Australia and New Zealand, which are close to the complete, prototypical form of settler colonialism.[7] However, settler colonialism is not restricted to any specific culture and has been practised by non-Europeans.[2] According to certain genocide scholars, including Raphael Lemkin – the individual who coined the term genocide – colonization is intrinsically genocidal.[8][9][10]

Origins as a theory

During the 1960s, settlement and colonization were perceived as separate phenomena from colonialism. Settlement endeavours were seen as taking place in empty areas, downplaying the Indigenous inhabitants. Later on in the 1970s and 1980s, settler colonialism was seen as bringing high living standards in contrast to the failed political systems associated with classical colonialism. Beginning in the mid-1990s, the field of settler colonial studies was established[11][page needed] distinct but connected to Indigenous studies.[12] Although often credited with originating the field, Australian historian Patrick Wolfe stated that "I didn't invent Settler Colonial Studies. Natives have been experts in the field for centuries."[13] Additionally, Wolfe's work was preceded by others that have been influential in the field, such as Fayez Sayegh's Zionist Colonialism in Palestine and Settler Capitalism by Donald Denoon.[13][11][page needed]

Definition and concept

Settler colonialism is a logic and structure, and not a mere occurrence. Settler colonialism takes claim of environments for replacing existing conditions and members of that environment with those of the settlement and settlers. Intrinsically connected to this is the displacement or elimination of existing residents, particularly through destruction of their environment and society.[1][2][3][4] As such, settler colonialism has been identified as a form of environmental racism.[14]

Some scholars describe the process as inherently genocidal, considering settler colonialism to entail the elimination of existing peoples and cultures,[15] and not only their displacement (see genocide, "the intentional destruction of a people in whole or in part").[citation needed] However, the opposite argument has also been made by Lorenzo Veracini, who argues that all genocide is settler colonial in nature.[16]

Depending on the definition, it may be enacted by a variety of means, including mass killing of the previous inhabitants, removal of the previous inhabitants and/or cultural assimilation.[17]

Therefore, colonial settling has been called an invasion or occupation, emphazising the violent reality of colonization and its settling, instead of the more domestic meaning of settling.[18]

Settler colonialism is distinct from migration because immigrants aim to join an existing society, not replace it.[19][20] Mahmood Mamdani writes, "Immigrants are unarmed; settlers come armed with both weapons and a nationalist agenda. Immigrants come in search of a homeland, not a state; for settlers, there can be no homeland without a state."[20] Nevertheless, the difference is often elided by settlers who minimize the voluntariness of their departure, claiming that settlers are mere migrants, and some pro-indigenous positions which militantly simplify, claiming that all migrants are settlers.[21]

The settler state is a state established through settler colonialism, by and for settlers.[22]

Examples

The settler colonial paradigm has been applied to a wide variety of conflicts around the world, including New Caledonia,[23] Western New Guinea,[24] the Andaman Islands, Argentina,[25] Australia, British Kenya, the Canary Islands,[26] Fiji, French Algeria,[27] Generalplan Ost, Hawaii,[28] Hokkaido, Ireland,[29] Israel/Palestine, Italian Libya and East Africa,[30][31] Kashmir,[32][33] Korea and Manchukuo,[34][35] Latin America, Liberia, New Zealand, northern Afghanistan,[36][37][38][39] North America, Posen and West Prussia and German South West Africa,[40] Rhodesia, Sápmi,[41][11][page needed][42] [43] South Africa, South Vietnam,[44][45][46] and Taiwan.[7][47]

Africa

Canary Islands

During the fifteenth century, the Kingdom of Castile sponsored expeditions by conquistadors to subjugate under Castilian rule the Macaronesian archipelago of the Canary Islands, located off the coast of Morocco and inhabited by the Indigenous Guanche people. Beginning with the start of the conquest of the island of Lanzarote on 1 May 1402 and ending with the surrender of the last Guanche resistance on Tenerife on 29 September 1496 to the now-unified Spanish crown, the archipelago was subject to a settler colonial process involving systematic enslavement, mass murder, and deportation of the Guanches, who were replaced with Spanish settlers, in a process foreshadowing the Iberian colonisation of the Americas that followed shortly thereafter. Also like in the Americas, Spanish colonialists in the Canaries quickly turned to the importation of slaves from mainland Africa as a source of labour due to the decimation of the already small Guanche population by a combination of war, disease, and brutal forced labour. Historian Mohamed Adhikari has labelled the conquest of the Canary Islands as the first overseas European settler colonial genocide.[26][41]

Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara

Since 1975, the Kingdom of Morocco has sponsored settlement schemes that have encouraged several thousand Moroccan citizens to settle Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara as part of the Western Sahara conflict. On 6 November 1975, the Green March took place, during which about 350,000 Moroccan citizens crossed into Saguia al-Hamra in the former Spanish Sahara after having received a signal from King Hassan II.[49] As of 2015, it is estimated that Moroccan settlers constitute two-thirds of the population of Western Sahara.[50]

Under international law, the transfer of Moroccan citizens into the occupied territory constitutes a direct violation of Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention (cf. Turkish settlers in Northern Cyprus and Israeli settlers in the Palestinian territories).[51]

South Africa

In 1652, the arrival of Europeans sparked the beginning of settler colonialism in South Africa. The Dutch East India Company was set up at the Cape, and imported large numbers of slaves from Africa and Asia during the mid-seventeenth century.[52] The Dutch East India Company established a refreshment station for ships sailing between Europe and the east. The initial plan by Dutch East India Company officer Jan van Riebeeck was to maintain a small community around the new fort, but the community continued to spread and settle further than originally planned.[53] There was a historic struggle to achieve the intended British sovereignty that was achieved in other parts of the Commonwealth. State sovereignty belonged to the Union of South Africa (1910–1961), followed by the Republic of South Africa (1961–1994) and finally the modern day Republic of South Africa (1994–present day).[52]

In 1948, the policy of Apartheid was introduced South Africa in order to segregate the races and ensure the domination of the Afrikaner minority over non-whites, politically, socially and economically.[54] As of 2014, the South African government has re-opened the period for land claims under the Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Act.[55]

Liberia

Liberia is often regarded by scholars as a unique example of settler colonialism and the only known instance of Black settler colonialism.[56] It is frequently described as an African American settler colony tasked with establishing a Western form of governance in Africa.[57]

Liberia was founded as the private colony of Liberia in 1822 by the American Colonization Society, a White American-run organization, to relocate free African Americans to Africa, as part of the Back-to-Africa movement.[58] This settlement scheme stemmed from fears that free African Americans would assist slaves in escaping, as well as the widespread belief among White Americans that African Americans were inherently inferior and should thus be relocated.[59] U.S. presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison publicly endorsed and funded the project.[58]

Between 1822 and the early 20th century, around 15,000 African Americans colonized Liberia on lands acquired from the region's indigenous African population. The African American elite monopolized the government and established minority rule over the locals. As they possessed Western culture, they felt superior to the natives, whom they dominated and oppressed.[60] Indigenous revolts against the Americo-Liberian elite such as the Grebo Revolt in 1909–1910 and Kru Revolt in 1915 were quelled with U.S. military support.[56][61]

North America

Canada

Attempts to assimilate the Indigenous peoples of what is now Canada were rooted in imperial colonialism centred around European worldviews and cultural practices, and a concept of land ownership based on the discovery doctrine.[62] Original assimilation efforts were religiously-oriented, beginning in the 17th century with the arrival of French missionaries in New France.[63] Although not without conflict, European Canadians' early interactions with First Nations and Inuit populations were relatively peaceful.[64] First Nations and Métis peoples (of mixed European and Indigenous ancestry) played a critical part in the development of European colonies in Canada, particularly for their role in assisting European coureur des bois and voyageurs in their explorations of the continent during the North American fur trade.[65]

The early European interactions with First Nations would change from Peace and Friendship Treaties to dispossession of lands through treaties and displacement legislation such as the Gradual Civilization Act,[66] the Indian Act, [67] the Potlatch ban,[68] and the pass system,[69] that focused on European ideals of Christianity, sedentary living, agriculture, and education.[70]

Indigenous groups in Canada continue to suffer from racially motivated discrimination, despite living in one of the most progressive countries in the world.[71] Discriminatory practices such as criminal justice inequity, police brutality, high incarnation rates, and high rates of violence against Indigenous women have been subject to legal and political review.[72]

United States

In colonial America, European powers created economic dependency and imbalance of trade, incorporating Indigenous nations into spheres of influence and controlling them indirectly with the use of Christian missionaries and alcohol.[73] With the emergence of an independent United States, desire for land and the perceived threat of permanent Indigenous political and spatial structures led to violent relocation of many Indigenous tribes to the American West, in what is known as the Trail of Tears.[17]

In response to American encroachment on native land in the Great Lakes region, the Pan-Indian confederacies of the Northwest Confederacy and Tecumseh's Confederacy emerged. Despite initial victories in both cases, such as St. Clair's defeat or the siege of Detroit, both eventually lost, thereby paving the way for American control over the region. Settlement into conquered land was rapid. Following the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, American settlers poured into southern Ohio, such that by 1810 it had a population of 230,760.[74] The defeat of the confederacies in the Great Lakes paved the way for large land loss in the region, via treaties such as the Treaty of Saginaw which saw the loss of more than 4,000,000 acres of land.[75]

Frederick Jackson Turner, the father of the "frontier thesis" of American history, noted in 1901: "Our colonial system did not start with Spanish War; the U.S. had had a colonial history from the beginning...hidden under the phraseology of 'interstate migration' and territorial organization'".[73] While the United States government and local state governments directly aided this dispossession through the use of military forces, ultimately this came about through agitation by settler society in order to gain access to Indigenous land. Especially in the US South, such land acquisition built plantation society and expanded the practice of slavery.[17] Settler colonialism participated in the formation of US cultures and lasted past the conquest, removal, or extermination of Indigenous people.[76][page needed] In 1928, Adolf Hitler spoke admiringly of the impact of white settler colonialism on the Natives, stating the US had "gunned down the millions of Redskins to a few hundred thousand, and now keep the modest remnant under observation in a cage".[77] The practice of writing the Indigenous out of history perpetrated a forgetting of the full dimensions and significance of colonialism at both the national and local levels.[73]

Asia

China

Near the end of their rule the Qing dynasty attempted to colonize Xinjiang, Tibet, and other parts of the imperial frontier. To accomplish this goal, they began resettling Han Chinese on the frontier.[78] This policy of settler colonialism was renewed by the People's Republic of China, led by Chinese Communist Party,[79][80] and is being practiced today according to some academics and researchers.[81][82][83]

Israel

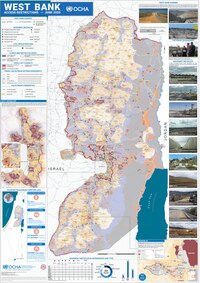

Zionism has been characterized by scholars such as the New Historians as a form of settler colonialism concerning the region of Palestine and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[86][87] This framework has also been embraced by activists.[88][89][90] This viewpoint has been criticised by other scholars due to its perceived denial of the historical Jewish connection to Palestine, among other reasons.[85][89][91] Many of the founding fathers of Zionism themselves described the project as colonization, such as Vladimir Jabotinsky, who said "Zionism is a colonization adventure."[92][93] Theodor Herzl, the founder of the World Zionist Organization, described the Zionist project as "something colonial" in a letter to Cecil Rhodes in 1902.[94]

In 1967, the French historian Maxime Rodinson wrote an article later translated and published in English as Israel: A Colonial Settler-State?,[95] but it was not until the 1990s that this viewpoint became more common in Israeli scholarship,[b][96] in part coinciding with increased support for a two state solution.[86] The Australian historian Patrick Wolfe, whose work is considered defining on the subject of settler colonialism, haz classified Israel as a modern form of settler colonialism.[13][17][7]

Lorenzo Veracini describes Israel as a "settler colonial polity", and writes that it could celebrate its anticolonial struggle in 1948 because it had colonial relationships inside and outside Israel's new borders.[97] Veracini believes the possibility of an Israeli disengagement is always latent and this relationship could be severed through a one state solution.[c] Other commentators, such as Daiva Stasiulis, Nira Yuval-Davis,[99] and Joseph Massad have included Israel in their global analysis of settler societies.[100] Ilan Pappé describes Zionism and Israel in similar terms.[101][102] Scholar Amal Jamal, from Tel Aviv University, has stated, "Israel was created by a settler-colonial movement of Jewish immigrants".[103] Damien Short has accused Israel of carrying out genocide against Palestinians during the Israeli–Palestinian conflict since its inception within a settler colonial context.[104]

Critics of the paradigm argue that Zionism does not fit the traditional framework of colonialism. S. Ilan Troen views Zionism as the return of an indigenous population to its historic homeland, distinct from imperial expansion.[105] Moses Lissak says that the settler-colonial thesis denies the idea that Zionism is the modern national movement of the Jewish people, seeking to reestablish a Jewish political entity in their historical territory. Lissak argues that Zionism was both a national movement and a settlement movement at the same time, so it was not, by definition, a colonial settlement movement.[106]

Russia and the Soviet Union

Some scholars describe Russia as a settler colonial state, particularly in its expansion into Siberia and the Russian Far East, during which it displaced and resettled Indigenous peoples, while practicing settler colonialism.[107][108][109] The annexation of Siberia and the Far East to Russia was resisted by the Indigenous peoples, while the Cossacks often committed atrocities against them.[110] During the Cold War, new forms of Indigenous repression were practiced.[111]

This colonization continued even during the Soviet Union in the 20th century.[112][page needed] The Soviet policy also sometimes included the deportation of the native population, as in the case of the Crimean Tatars.[113]

Taiwan

According to a PhD thesis by Lin-chin Tsai, current ethnic makeup of Taiwan is largely the result of Chinese settler colonialism beginning in the seventeenth century.[114]

Australia

Europeans explored and settled Australia, displacing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The Indigenous Australian population was estimated at 795,000 at the time of European settlement.[115] The population declined steeply for 150 years following settlement from 1788, due to casualties from infectious disease, the Australian frontier wars and forced re-settlement and cultural disintegration.[116][117]

Responses

Settler colonialism exists in tension with indigenous studies. Some indigenous scholars believe that settler colonialism as a methodology can lead to overlooking indigenous responses to colonialism; however, other practitioners of indigenous studies believe that settler colonialism has important insights that are applicable to their work.[13] Settler colonialism as a theory has also been criticized from the standpoint of postcolonial theory.[13] Antiracism has been criticized on the basis that it does not provide a special status for indigenous claims, and in response settler colonial theory has been criticized for potentially contributing to the marginalization of racialized immigrants.[118]

Political theorist Mahmoud Mamdani suggested that settlers could never succeed in their effort to become native, and therefore the only way to end settler colonialism was to erase the political significance of the settler–native dichotomy.[7]

According to Chickasaw scholar Jodi Byrd, in contrast to settler, the term arrivant refers to enslaved Africans transported against their will, and to refugees forced into the Americas due to the effects of imperialism.[119]

In his book Empire of the People: Settler Colonialism and the Foundations of Modern Democratic Thought, political scientist Adam Dahl states that while it has often been recognized that "American democratic thought and identity arose out of the distinct pattern by which English settlers colonized the new world", histories are missing the "constitutive role of colonial dispossession in shaping democratic values and ideals".[120]

See also

Notes

- ^ Example reconciliation programmes include: Reconciliation in Australia, and truth and reconciliation commissions in Canada, Norway and South Africa.

- ^ Sabbagh-Khoury writes: "The settler colonial paradigm, linked to Israeli critical sociology, post-Zionism, and postcolonialism, reemerged following changes in the political landscape from the mid-1990s that reframed the history of the Nakba as enduring, challenged the Jewish definition of the state, and legitimated Palestinians as agents of history. Palestinian scholars in Israel lead the paradigm's reformulation."</ref>[86]

- ^ Veracini says this could be an "accommodation of a Palestinian Israeli autonomy within the institutions of the Israeli state]]".[98][page needed]

References

- ^ a b Carey, Jane; Silverstein, Ben (2 January 2020). "Thinking with and beyond settler colonial studies: new histories after the postcolonial". Postcolonial Studies. 23 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/13688790.2020.1719569. hdl:1885/204080. ISSN 1368-8790. S2CID 214046615.

The key phrases Wolfe coined here – that invasion is a 'structure not an event'; that settler colonial structures have a 'logic of elimination' of Indigenous peoples; that 'settlers come to stay' and that they 'destroy to replace' – have been taken up as the defining precepts of the field and are now cited by countless scholars across numerous disciplines.

- ^ a b c Veracini, Lorenzo (2017). "Introduction: Settler colonialism as a distinct mode of domination". In Cavanagh, Edward; Veracini, Lorenzo (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of the History of Settler Colonialism. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-415-74216-0.

Settler colonialism is a relationship. It is related to colonialism but also inherently distinct from it. As a system defined by unequal relationships (like colonialism) where an exogenous collective aims to locally and permanently replace indigenous ones (unlike colonialism), settler colonialism has no geographical, cultural or chronological bounds. It is culturally nonspecific ... It can happen at any time, and everyone is a settler if they are part of a collective and sovereign displacement that moves to stay, that moves to establish a permanent homeland by way of displacement.

- ^ a b McKay, Dwanna L.; Vinyeta, Kirsten; Norgaard, Kari Marie (September 2020). "Theorizing race and settler colonialism within U.S. sociology". Sociology Compass. 14 (9). doi:10.1111/soc4.12821. ISSN 1751-9020. S2CID 225377069.

Settler-colonialism describes the logic and operation of power when colonizers arrive and settle on lands already inhabited by another group. Importantly, settler colonialism operates through a logic of elimination, seeking to eradicate the original inhabitants through violence and other genocidal acts and to replace the existing spiritual, epistemological, political, social, and ecological systems with those of the settler society.

- ^ a b Whyte, Kyle (1 September 2018). "Settler Colonialism, Ecology, and Environmental Injustice". Environment and Society. 9 (1): 125–144. doi:10.3167/ares.2018.090109. ISSN 2150-6779.

- ^ LeFevre, Tate. "Settler Colonialism". oxfordbibliographies.com. Tate A. LeFevre. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

Though often conflated with colonialism more generally, settler colonialism is a distinct imperial formation. Both colonialism and settler colonialism are premised on exogenous domination, but only settler colonialism seeks to replace the original population of the colonized territory with a new society of settlers (usually from the colonial metropole).

- ^ Veracini, Lorenzo (October 2007). "Settler Colonialism and Decolonisation". Borderlands. 6 (2).

- ^ a b c d Englert, Sai (2020). "Settlers, Workers, and the Logic of Accumulation by Dispossession". Antipode. 52 (6): 1647–1666. Bibcode:2020Antip..52.1647E. doi:10.1111/anti.12659. hdl:1887/3220822. S2CID 225643194.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson, Douglas (2020). "Raphaël Lemkin: Genocide, cultural violence, and community destruction". In Greenland, Fiona; Göçek, Fatma Müge (eds.). Cultural Violence and the Destruction of Human Communities. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781351267083-3. ISBN 978-1-351-26708-3. S2CID 234701072.

In a footnote, he added that genocide could equally be termed 'ethnocide', with the Greek ethno meaning 'nation'.

- ^ Short, Damien (2016). Redefining Genocide: Settler Colonialism, Social Death and Ecocide. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-84813-546-8. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ Moses, A. Dirk (2008). "Empire, Colony, Genocide: Keywords and the Philosophy of History". In Moses, A. Dirk (ed.). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. Berghahn Books. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-1-84545-452-4.

Extra-European colonial cases also featured prominently in this projected global history of genocide. In 'Part III: Modern Times,' he wrote the following numbered chapters: (1) Genocide by the Germans against the Native Africans; (3) Belgian Congo; (11) Hereros; (13) Hottentots; (16) Genocide against the American Indians; (25) Latin America; (26) Genocide against the Aztecs; (27) Yucatan; (28) Genocide against the Incas; (29) Genocide against the Maoris of New Zealand; (38) Tasmanians; (40) S.W. Africa; and finally, (41) Natives of Australia ... While Lemkin's linking of genocide and colonialism may surprise those who think that his neologism was modeled after the Holocaust of European Jewry, an investigation of his intellectual development reveals that the concept is the culmination of a long tradition of European legal and political critique of colonization and empire.

- ^ a b c Veracini 2013.

- ^ Shoemaker, Nancy (1 October 2015). "A Typology of Colonialism | Perspectives on History". American Historical Association. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Kauanui, J. Kēhaulani (3 April 2021). "False dilemmas and settler colonial studies: response to Lorenzo Veracini: 'Is Settler Colonial Studies Even Useful?'". Postcolonial Studies. 24 (2): 290–296. doi:10.1080/13688790.2020.1857023. ISSN 1368-8790. S2CID 233986432.

- ^ Van Sant, Levi; Milligan, Richard; Mollett, Sharlene (2021). "Political Ecologies of Race: Settler Colonialism and Environmental Racism in the United States and Canada". Antipode. 53 (3): 629–642. Bibcode:2021Antip..53..629V. doi:10.1111/anti.12697. ISSN 0066-4812.

- ^ Short, Damien (2016). Redefining Genocide: Settler Colonialism, Social Death and Ecocide. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-84813-546-8.

- ^ Veracini, Lorenzo (2021). "Colonialism, Frontiers, Genocide: Civilian-Driven Violence in Settler Colonial Situations". Civilian-Driven Violence and the Genocide of Indigenous Peoples in Settler Societies. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-41177-5.

not only is genocide necessarily settler colonial (even though settler colonialism is not always genocidal or even successful)

- ^ a b c d e Wolfe, Patrick (2006). "Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native". Journal of Genocide Research. 8 (4): 387–409. doi:10.1080/14623520601056240. ISSN 1462-3528. S2CID 143873621.

- ^ Kilroy, Peter (22 May 2024). "Discovery, settlement or invasion? The power of language in Australia's historical narrative". The Conversation. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ Veracini 2015, p. 40.

- ^ a b Mamdani 2020, p. 253.

- ^ Veracini 2015, p. 35.

- ^ Tozer, Angela (2021). "Democracy in a Settler State?: Settler Colonialism and the Development of Canada, 1820–67". Constant Struggle: Histories of Canadian Democratization. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 87–115. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1z7kjww.7. ISBN 978-0-2280-0866-8. JSTOR j.ctv1z7kjww.7. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ "New Caledonia set for 2nd referendum on independence from France". Al Jazeera. 3 October 2020.

- ^ McNamee, Lachlan (15 May 2020). "Indonesian Settler Colonialism in West Papua". SSRN 3601528.

- ^ Larson, Carolyne R. (2020). The Conquest of the Desert: Argentina's Indigenous Peoples and the Battle for History. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826362087.

- ^ a b Adhikari, Mohamed (7 September 2017). "Europe's First Settler Colonial Incursion into Africa: The Genocide of Aboriginal Canary Islanders". African Historical Review. 49 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1080/17532523.2017.1336863. S2CID 165086773. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Barclay, Fiona; Chopin, Charlotte Ann; Evans, Martin (12 January 2017). "Introduction: settler colonialism and French Algeria". Settler Colonial Studies. 8 (2): 115–130. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2016.1273862. hdl:1893/25105. S2CID 151527670.

- ^ Takumi, Roy (1994). "Challenging U.S. Militarism in Hawai'i and Okinawa". Race, Poverty & the Environment. 4/5 (4/1): 8–9. ISSN 1532-2874. JSTOR 41555279.

- ^ Connolly, S. (2017). Settler colonialism in Ireland from the English conquest to the nineteenth century. In E. Cavanagh, & L. Veracini (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of the History of Settler Colonialism (pp. 49-64). Article 4 Routledge.

- ^ Ertola, Emanuele (15 March 2016). "'Terra promessa': migration and settler colonialism in Libya, 1911–1970". Settler Colonial Studies. 7 (3): 340–353. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2016.1153251. S2CID 164009698. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Veracini, Lorenzo (Winter 2018). "Italian Colonialism through a Settler Colonial Studies Lens". Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History. 19 (3). doi:10.1353/cch.2018.0023. S2CID 165512037. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Raman, Anita D. (2004). "Of Rivers and Human Rights: The Northern Areas, Pakistan's forgotten colony in Jammu and Kashmir". International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. 11 (1/2): 187–228. doi:10.1163/157181104323383929. JSTOR 24675261.

- ^ Mushtaq, Samreen; Mudasir, Amin (16 October 2021). "'We will memorise our home': exploring settler colonialism as an interpretive framework for Kashmir". Third World Quarterly. 42 (12): 3012–3029. doi:10.1080/01436597.2021.1984877. S2CID 244607271. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Lu, Sidney Xu (June 2019). "Eastward Ho! Japanese Settler Colonialism in Hokkaido and the Making of Japanese Migration to the American West, 1869–1888". The Journal of Asian Studies. 78 (3): 521–547. doi:10.1017/S0021911819000147. S2CID 197847093. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Uchida, Jun (3 March 2014). Brokers of Empire: Japanese Settler Colonialism in Korea, 1876–1945. Vol. 337. Harvard University Asia Center. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1x07x37. ISBN 978-0674492028. JSTOR j.ctt1x07x37. S2CID 259606289.

- ^ Christian Bleuer (2012). "State-building, migration and economic development on the frontiers of northern Afghanistan and southern Tajikistan". Journal of Eurasian Studies. 3: 69–79. doi:10.1016/j.euras.2011.10.008.

- ^ Bleuer, Christian (17 October 2014). "From 'Slavers' to 'Warlords': Descriptions of Afghanistan's Uzbeks in Western Writing". Afghanistan Analysts Network.

- ^ Mundt, Alex; Schmeidl, Susanne; Ziai, Shafiqullah (1 June 2009). "Between a Rock and a Hard Place: The Return of Internally Displaced Persons to Northern Afghanistan". Brookings Institution.

- ^ "Paying for the Taliban's Crimes: Abuses Against Ethnic Pashtuns in Northern Afghanistan" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. April 2002.

- ^ Lerp, Dörte (11 October 2013). "Farmers to the Frontier: Settler Colonialism in the Eastern Prussian Provinces and German Southwest Africa". Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 41 (4): 567–583. doi:10.1080/03086534.2013.836361. S2CID 159707103. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ a b Adhikari, Mohamed (25 July 2022). Destroying to Replace: Settler Genocides of Indigenous Peoples. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. pp. 1–32. ISBN 978-1647920548.

- ^ Browning, Christopher R. (8 February 2022). "Yehuda Bauer, the Concepts of Holocaust and Genocide, and the Issue of Settler Colonialism". The Journal of Holocaust Research. 36 (1): 30–38. doi:10.1080/25785648.2021.2012985. S2CID 246652960. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ Rahman, Smita A.; Gordy, Katherine A.; Deylami, Shirin S. (2022). Globalizing Political Theory. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000788884.

- ^ Salemink, Oscar (2003). The Ethnography of Vietnam's Central Highlanders: A Historical Contextualization, 1850–1990. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 35–336. ISBN 978-0-8248-2579-9.

- ^ Nguyen, Duy Lap (2019). The unimagined community: Imperialism and culture in South Vietnam. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-52614-398-3.

- ^ Schweyer, Anne-Valérie (2019). "The Chams in Vietnam: a great unknown civilization". French Academic Network of Asian Studies. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ Tsai, Lin-chin (2019). Re-conceptualizing Taiwan: Settler Colonial Criticism and Cultural Production (Thesis). UCLA.

- ^ Cowan, L. Gray (1964). The Dilemmas of African Independence. New York: Walker & Company, Publishers. pp. 42–55, 105. ASIN B0007DMOJ0.

- ^ Hamdaoui, Neijma (31 October 2003). "Hassan II lance la Marche verte" [Hassan II launches the Green March]. JeuneAfrique.com (in French). Archived from the original on 3 January 2006. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Shefte, Whitney (6 January 2015). "Western Sahara's stranded refugees consider renewal of Morocco conflict". The Guardian.

- ^ "Mixed Reviews for Morocco as Fourth Committee Hears Petitioners on Western Sahara, Amid Continuing Decolonization Debate | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases". United Nations.

- ^ a b Cavanagh, E (2013). Settler colonialism and land rights in South Africa: Possession and dispossession on the Orange River. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 10–16. ISBN 978-1-137-30577-0.

- ^ Fourie, J (2014). "Settler Skills and Colonial Development: The Huguenot Wine-Makers in Eighteenth-Century Dutch South Africa". Economic History Review. 67 (4): 932–963. doi:10.1111/1468-0289.12033. S2CID 152735090.

- ^ Mayne, Alan (1999). From Politics Past to Politics Future: An Integrated Analysis of Current and Emergent Paradigms. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-275-96151-0.

- ^ Weinberg, T (2015). "The Griqua Past and the Limits of South African History, 1902–1994; Settler Colonialism and Land Rights in South Africa: Possession and Dispossession on the Orange River". Journal of Southern African Studies. 41: 211–214. doi:10.1080/03057070.2015.991591. S2CID 144750398.

- ^ a b Spence, David M. (2021). "From Victims to Colonizers" (PDF). The SOAS Journal of Postgraduate Research.

- ^ Parkins, Daniel (2019). "Colonialism, Postcolonialism, and the Drive for Social Justice: A Historical Analysis of Identity Based Conflicts in the First Republic of Liberia". SIT Graduate Institute.

- ^ a b "Founding of Liberia, 1847". Office of the Historian. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Nicholas Guyatt, “The American Colonization Society: 200 Years of the “Colonizing Trick”, Black Perspectives, African American Intellectual History Society, December 22, 2016; Nicholas Guyatt, “The American Colonization Society’s plans for abolishing slavery,” Oxford University Press’s Academic Insights for the Thinking World, December 22, 2016, /.

- ^ Akpan, M. B. (10 March 2014). "Black Imperialism: Americo-Liberian Rule over the African Peoples of Liberia, 1841–1964". Canadian Journal of African Studies (in French). 7 (2): 217–236. doi:10.1080/00083968.1973.10803695. ISSN 0008-3968.

- ^ "Liberia: The African-American settler colony that parallels Israel". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "The Doctrine of Discovery". CMHR. 2 November 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ Gourdeau, Claire. "Population – Religious Congregations". Virtual Museum of New France. Canadian Museum of History. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ Preston, David L. (2009). The Texture of Contact: European and Indian Settler Communities on the Frontiers of Iroquoia, 1667–1783. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-8032-2549-7. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ Miller, J. R. (2009). Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4426-9227-5. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "Gradual Civilization Act, 1857" (PDF). Government of Canada. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2024. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Indian Act". Site Web de la législation (Justice). 15 August 2019. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ "Potlatch Ban". The Canadian Encyclopedia. 11 January 2024. Archived from the original on 16 August 2024. Retrieved 3 September 2024.

- ^ What We Have Learned: Principles of Truth and Reconciliation (PDF) (Report). 2015. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-660-02073-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2021.

- ^

- Williams, L. (2021). Indigenous Intergenerational Resilience: Confronting Cultural and Ecological Crisis. Routledge Studies in Indigenous Peoples and Policy. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-000-47233-2. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- Turner, N. J. (2020). Plants, People, and Places: The Roles of Ethnobotany and Ethnoecology in Indigenous Peoples' Land Rights in Canada and Beyond. McGill-Queen's Indigenous and Northern Studies. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-2280-0317-5. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- Asch, Michael (1997). Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada: Essays on Law, Equity, and Respect for Difference. University of British Columbia Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7748-0581-0.

- Kirmayer, Laurence J.; Guthrie, Gail Valaskakis (2009). Healing Traditions: The Mental Health of Aboriginal Peoples in Canada. University of British Columbia Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7748-5863-2.

- "Indigenous Peoples and Government Policy in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. 6 June 1944. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ Snelgrove, Corey; Dhamoon, Rita Kaur; Corntassel, Jeff (2014). "Unsettling settler colonialism: The discourse and politics of settlers, and solidarity with Indigenous nations" (PDF). Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society. 3 (2): 11–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2017.

- ^ "Understanding the Overrepresentation of Indigenous People". State of the Criminal Justice System Dashboard. 11 June 2024. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ a b c Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne (2014). An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-0040-3.

- ^ https://www.issuelab.org/resources/3973/3973.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "The 1819 Treaty of Saginaw". 26 November 2019.

- ^ Spady, James O'Neil (2020). Education and the Racial Dynamics of Settler Colonialism in Early America: Georgia and South Carolina, ca. 1700 - ca. 1820. Routledge. ISBN 978-0367437169.

- ^ Moon, David (2020). The American Steppes. Cambridge University Press. p. 44.

- ^ Wang, Ju-Han Zoe; Roche, Gerald (16 March 2021). "Urbanizing Minority Minzu in the PRC: Insights from the Literature on Settler Colonialism". Modern China. 48 (3): 593–616. doi:10.1177/0097700421995135. ISSN 0097-7004. S2CID 233620981.

- ^ Brooks, Jonathan (2021), Settler Colonialism, Primitive Accumulation, and Biopolitics in Xinjiang, China, doi:10.2139/ssrn.3965577, ISSN 1556-5068, SSRN 3965577

- ^ Clarke, Michael (16 February 2021). "Settler Colonialism and the Path toward Cultural Genocide in Xinjiang". Global Responsibility to Protect. 13 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1163/1875-984X-13010002. ISSN 1875-9858. S2CID 233974395.

- ^ Ramanujan, Shaurir (9 December 2022). "Reclaiming the Land of the Snows: Analyzing Chinese Settler Colonialism in Tibet". The Columbia Journal of Asia. 1 (2): 29–36. doi:10.52214/cja.v1i2.10012. ISSN 2832-8558.

- ^ Finley, Joanne Smith (1 September 2022). "Tabula rasa: Han settler colonialism and frontier genocide in "re-educated" Xinjiang". HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory. 12 (2): 341–356. doi:10.1086/720902. ISSN 2575-1433. S2CID 253268699.

- ^ McGranahan, Carole (17 December 2019). "Chinese Settler Colonialism: Empire and Life in the Tibetan Borderlands". In Gros, Stéphane (ed.). Frontier Tibet: Patterns of Change in the Sino-Tibetan Borderlands. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 517–540. doi:10.2307/j.ctvt1sgw7.22. ISBN 978-90-485-4490-5. JSTOR j.ctvt1sgw7.22.

- ^ a b Powell, Michael (5 January 2024). "The Curious Rise of 'Settler Colonialism' and 'Turtle Island'". The Atlantic. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ a b Troen, S. Ilan (2007). "De-Judaizing the Homeland: Academic Politics in Rewriting the History of Palestine". Israel Affairs. 13 (4): 872–884. doi:10.1080/13537120701445372. S2CID 216148316.

- ^ a b c Sabbagh-Khoury, Areej (2022). "Tracing Settler Colonialism: A Genealogy of a Paradigm in the Sociology of Knowledge Production in Israel". Politics & Society. 50 (1): 44–83. doi:10.1177/0032329221999906. S2CID 233635930.

- ^ Jamal, Amal (2017). "Neo-Zionism and Palestine: The Unveiling of Settler-Colonial Practices in Mainstream Zionism". Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies. 16 (1): 47–78. doi:10.3366/hlps.2017.0152. ISSN 2054-1988.

- ^ Tawil-Souri, Helga (2016). "Response to Elia Zureik's Israel's Colonial Project in Palestine: Brutal Pursuit". Arab Studies Quarterly. 38 (4): 683–687. doi:10.13169/arabstudquar.38.4.0683. ISSN 0271-3519. JSTOR 10.13169/arabstudquar.38.4.0683. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

Calling Israel a settler colonial regime is an argument increasingly gaining purchase in activist and, to a lesser extent, academic circles.

- ^ a b Schuessler, Jennifer (22 January 2024). "What Is 'Settler Colonialism'?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Kirsch, Adam (26 October 2023). "Campus Radicals and Leftist Groups Have Embraced the Idea of 'Settler Colonialism'". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Cohen, Roger (10 December 2023). "Who's a 'Colonizer'? How an Old Word Became a New Weapon". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Hart, Alan (13 August 2010). Zionism: The Real Enemy of the Jews. Vol. 1: The False Messiah. SCB Distributors. ISBN 978-0-932863-78-2.

A voluntary reconciliation with the Arabs is out of the question either now or in the future. If you wish to colonize a land in which people are already living, you must provide a garrison for the land, or find some rich man or benefactor who will provide a garrison on your behalf. Or else-or else, give up your colonization, for without an armed force which will render physically impossible any attempt to destroy or prevent this colonization, colonization is impossible, not difficult, not dangerous, but IMPOSSIBLE!... Zionism is a colonization adventure and therefore it stands or falls by the question of armed force. It is important... to speak Hebrew, but, unfortunately, it is even more important to be able to shoot – or else I am through with playing at colonizing.

- ^ Jabotinsky, Ze'ev (4 November 1923). "The Iron Wall" (PDF).

Colonisation can have only one aim, and Palestine Arabs cannot accept this aim. It lies in the very nature of things, and in this particular regard nature cannot be changed...Zionist colonisation must either stop, or else proceed regardless of the native population.

- ^ Gelber, Mark H.; Liska, Vivian, eds. (2012). Theodor Herzl: From Europe to Zion. De Gruyter. pp. 100–101.

- ^ Rodinson, Maxime. "Israel, fait colonial?" Les Temps Moderne, 1967. Republished in English as Israel: A Colonial Settler-State?, New York, Monad Press, 1973.

- ^ Jamal 2017, pp. 47–8.

- ^ Veracini, Lorenzo (2007). "Settler Colonialism and Decolonisation". borderlands e-journal. 6 (2). Archived from the original on 30 March 2020.

Israel could celebrate its anticolonial/anti-British struggle exactly because it was able to establish a number of colonial relationships within and without the borders of 1948.

- ^ Veracini, Lorenzo (2006). Israel and Settler Society. London: Pluto Press.

- ^ Unsettling Settler Societies: Articulations of Gender, Race, Ethnicity and Class, Vol. 11, Nira Yuval-Davis (Editor), Daiva K Stasiulis (Editor), Paperback 352pp, ISBN 978-0-8039-8694-7, August 1995 SAGE Publications.

- ^ "Post Colonial Colony: time, space and bodies in Palestine/Israel in the persistence of the Palestinian Question", Routledge, NY, (2006) and "The Pre-Occupation of Post-Colonial Studies" ed. Fawzia Afzal-Khan and Kalpana Rahita Seshadri. (Durham: Duke University Press)

- ^ The Palestinian Enclaves Struggle: An Interview with Ilan Pappé Archived 19 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, King's Review – Magazine

- ^ Video: Decolonizing Israel. Ilan Pappé on Viewing Israel-Palestine Through the Lens of Settler-Colonialism. Antiwar.com, 5 April 2017

- ^ Amal Jamal (2011). Arab Minority Nationalism in Israel: The Politics of Indigeneity. Taylor & Francis. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-136-82412-8.

- ^ Short, Damien (December 2012). "Genocide and settler colonialism: can a Lemkin-inspired genocide perspective aid our understanding of the Palestinian situation?". The International Journal of Human Rights.

- ^ Troen, S. Ilan (2007). "De-Judaizing the Homeland: Academic Politics in Rewriting the History of Palestine". Israel Affairs. 13 (4): 872–884. doi:10.1080/13537120701445372. S2CID 216148316.

- ^ Moshe Lissak, "'Critical' Sociology and 'Establishment' Sociology in the Israeli Academic Community: Ideological Struggles or Academic Discourse?" Israel Studies 1:1 (1996), 247-294.

- ^ Sunderland, Willard (2000). "The 'Colonization Question': Visions of Colonization in Late Imperial Russia". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. 48 (2): 210–232. JSTOR 41050526.

- ^ Forsyth, James (1992). A history of the peoples of Siberia. Internet Archive. Cambridge University Press. pp. 201–228, 241–346. ISBN 978-0-521-40311-5.

- ^ Lantzeff, George V.; Pierce, Richard A. (1973). Eastward to Empire: Exploration and Conquest on the Russian Open Frontier to 1750. McGill-Queen's University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1w0dbpp. JSTOR j.ctt1w0dbpp.

- ^ Hill, Nathaniel (25 October 2021). "Conquering Siberia: The Case for Genocide Recognition". www.genocidewatchblog.com. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ Bartels, Dennis; Bartels, Alice L. (2006). "Indigenous Peoples of the Russian North and Cold War Ideology". Anthropologica. 48 (2): 265–279. doi:10.2307/25605315. JSTOR 25605315.

- ^ Veracini 2013: "The domination of Latin America, North America, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the Asian part of the Soviet Union by European powers all involved the migration of permanent settlers from the European country to the colonies. These places were colonized."

- ^ Pohl, Otto (2015). "The Deportation of the Crimean Tatars in the Context of Settler Colonialism". International Crimes and History (16). Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Tsai, Lin-chin (2019). Re-conceptualizing Taiwan: Settler Colonial Criticism and Cultural Production (PhD thesis). University of California. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

Taiwan, an island whose indigenous inhabitants are Austronesian, has been a de facto settler colony due to large-scale Han migration from China to Taiwan beginning in the seventeenth century.

- ^ Statistics compiled by Ørsted-Jensen for Frontier History Revisited (Brisbane 2011), page 15.

- ^ Page, A. (September 2015). "The Australian Settler State, Indigenous Agency, and the Indigenous Sector in the Twenty First Century" (PDF). Australian Political Studies Association Conference. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Page, A.; Petray, T. (2015). "Agency and Structural Constraints: Indigenous Peoples and the Settler-State in North Queensland". Settler Colonial Studies. 5 (2).

- ^ Veracini 2015, p. 44.

- ^ Byrd, Jodi A. (6 September 2011). The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism. University of Minnesota Press. pp. xix. ISBN 978-1-4529-3317-7.

- ^ Dahl 2018, p. 1.

Works cited

- Dahl, Adam (2018). Empire of the People: Settler Colonialism and the Foundations of Modern Democratic Thought. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2607-6.

- Veracini, Lorenzo (2013). "'Settler Colonialism': Career of a Concept". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 41 (2): 313–333. doi:10.1080/03086534.2013.768099. hdl:1959.3/353066. S2CID 159666130. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

Further reading

- Adhikari, Mohamed (2021). Civilian-Driven Violence and the Genocide of Indigenous Peoples in Settler Societies. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-41177-5.

- Cox, Alicia. "Settler Colonialism". Oxford Bibliographies. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- Englert, Sai (2022). Settler Colonialism: An Introduction. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-4490-4.

- Belich, James (2009). Replenishing the earth: the settler revolution and the rise of the Anglo-world, 1783–1939. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 573. ISBN 978-0-19-929727-6.

- Horne, Gerald. The Apocalypse of Settler Colonialism: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, and Capitalism in Seventeenth-Century North America and the Caribbean. Monthly Review Press, 2018. 243p. ISBN 9781583676639

- Horne, Gerald. The Dawning of the Apocalypse: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism, and Capitalism in the Long Sixteenth Century. Monthly Review Press, 2020. ISBN 978-1-58367-875-6.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (2020). Neither Settler nor Native. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-98732-6.

- Manjapra, Kris (2020). "Settlement". Colonialism in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–70. ISBN 978-1-108-42526-1.

- Marx, Christoph (2017). Settler Colonies, EGO - European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, retrieved: March 17, 2021 (pdf).

- Mikdashi, Maya (2013). What is settler colonialism? American Indian Culture and Research Journal 37.2: 23–34.

- Pedersen, Susan; Elkins, Caroline, eds. (2005). Settler Colonialism in the Twentieth Century. Routledge.

- Sakai, J. (1983). Settlers: The Mythology of the White Proletariat. PM Press. ISBN 978-1-62963-037-3.

- Veracini, Lorenzo (2010). Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 182. ISBN 9780230284906.

- Veracini, Lorenzo (2015). The Settler Colonial Present. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-37247-5.

- Wolfe, Patrick (2016). Traces of History: Elementary Structures of Race. Verso Books.