Oxazepam

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ɒkˈsæzɪpæm/ ok-SAZ-i-pam |

| Trade names | Serax, Alepam, Serepax, others |

| Addiction liability | Low–moderate |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Benzodiazepine |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 92.8% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (glucuronidation) |

| Onset of action | 30 - 120 minutes |

| Elimination half-life | 6–9 hours[3][4][5] |

| Duration of action | 6 - 12 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.009.161 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

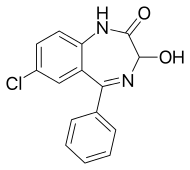

| Formula | C15H11ClN2O2 |

| Molar mass | 286.71 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 205 to 206 °C (401 to 403 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Oxazepam is a short-to-intermediate-acting benzodiazepine.[7][8] Oxazepam is used for the treatment of anxiety,[9][10] insomnia, and to control symptoms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome.

It is a metabolite of diazepam, prazepam, and temazepam,[11] and has moderate amnesic, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, sedative, and skeletal muscle relaxant properties compared to other benzodiazepines.[12]

It was patented in 1962 and approved for medical use in 1964.[13]

Medical uses

[edit]It is an intermediate-acting benzodiazepine with a slow onset of action,[14] so it is usually prescribed to individuals who have trouble staying asleep, rather than falling asleep. It is commonly prescribed for anxiety disorders with associated tension, irritability, and agitation. It is also prescribed for drug and alcohol withdrawal, and for anxiety associated with depression. Oxazepam is sometimes prescribed off-label to treat social phobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, insomnia, premenstrual syndrome, and other conditions.[15]

Side effects

[edit]The side effects of oxazepam are similar to those of other benzodiazepines, and may include dizziness, drowsiness, headache, memory impairment, paradoxical excitement, and anterograde amnesia, but does not affect transient global amnesia.[citation needed] Withdrawal effects due to rapid decreases in dosage or abrupt discontinuation of oxazepam may include abdominal and muscle cramps, seizures, depression, insomnia, sweating, tremors, or nausea and vomiting.[16]

In September 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required the boxed warning be updated for all benzodiazepine medicines to describe the risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions consistently across all the medicines in the class.[17]

Tolerance, dependence and withdrawal

[edit]Oxazepam, as with other benzodiazepine drugs, can cause tolerance, physical dependence, addiction, and benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Withdrawal from oxazepam or other benzodiazepines often leads to withdrawal symptoms which are similar to those seen during alcohol and barbiturate withdrawal. The higher the dose and the longer the drug is taken, the greater the risk of experiencing unpleasant withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms can occur, though, at standard dosages and also after short-term use. Benzodiazepine treatment should be discontinued as soon as possible by a slow and gradual dose reduction regimen.[18]

Contraindications

[edit]Oxazepam is contraindicated in myasthenia gravis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and limited pulmonary reserve, as well as severe hepatic disease.

Special precautions

[edit]Benzodiazepines require special precautions if used in the elderly, during pregnancy, in children, alcohol- or drug-dependent individuals, and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[19] Benzodiazepines including oxazepam are lipophilic drugs and rapidly penetrate membranes, so rapidly crosses over into the placenta with significant uptake of the drug. Use of benzodiazepines in late pregnancy, especially high doses, may result in floppy infant syndrome.[20]

Pregnancy

[edit]Oxazepam, when taken during the third trimester, causes a definite risk to the neonate, including a severe benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome including hypotonia, reluctance to suck, apnoeic spells, cyanosis, and impaired metabolic responses to cold stress. Floppy infant syndrome and sedation in the newborn may also occur. Symptoms of floppy infant syndrome and the neonatal benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome have been reported to persist from hours to months after birth.[21]

Interactions

[edit]As oxazepam is an active metabolite of diazepam, an overlap in possible interactions is likely with other drugs or food, with exception of the pharmacokinetic CYP450 interactions (e.g. with cimetidine). Precautions and following the prescription are required when taking oxazepam (or other benzodiazepines) in combinations with antidepressants or opioids. Concurrent use of these medications can interact in a way that is difficult to predict. Drinking alcohol when taking oxazepam is not recommended. Concomitant use of oxazepam and alcohol can lead to increased sedation, memory impairment, ataxia, decreased muscle tone, and, in severe cases or in predisposed patients, respiratory depression and coma.

Overdose

[edit]Oxazepam is generally less toxic in overdose than other benzodiazepines.[22] Important factors which affect the severity of a benzodiazepine overdose include the dose ingested, the age of the patient, and health status prior to overdose. Benzodiazepine overdoses can be much more dangerous if a coingestion of other CNS depressants such as opiates or alcohol has occurred. Symptoms of an oxazepam overdose include:[23][24][25]

- Respiratory depression

- Excessive somnolence

- Altered consciousness

- Central nervous system depression

- Occasionally cardiovascular and pulmonary toxicity

- Rarely, deep coma

Pharmacology

[edit]Oxazepam is an intermediate-acting benzodiazepine of the 3-hydroxy family; it acts on benzodiazepine receptors, resulting in increased effect of GABA to the GABAA receptor which results in inhibitory effects on the central nervous system.[26][27] The half-life of oxazepam is between 6 and 9 hours.[5][4][28] It has been shown to suppress cortisol levels.[29] Oxazepam is the most slowly absorbed and has the slowest onset of action of all the common benzodiazepines according to one British study.[30]

Oxazepam is an active metabolite formed during the breakdown of diazepam, nordazepam, and certain similar drugs. It may be safer than many other benzodiazepines in patients with impaired liver function because it does not require hepatic oxidation, but rather, it is simply metabolized by glucuronidation, so oxazepam is less likely to accumulate and cause adverse reactions in the elderly or people with liver disease. Oxazepam is similar to lorazepam in this respect.[31] Preferential storage of oxazepam occurs in some organs, including the heart of the neonate. Absorption by any administered route and the risk of accumulation is significantly increased in the neonate, and withdrawal of oxazepam during pregnancy and breast feeding is recommended, as oxazepam is excreted in breast milk.[32]

2 mg of oxazepam equates to 1 mg of diazepam according to the benzodiazepine equivalency converter, therefore 20 mg of oxazepam according to BZD equivalency equates to 10 mg of diazepam and 15 mg oxazepam to 7.5 mg diazepam (rounded up to 8 mg of diazepam).[33] Some BZD equivalency converters use 3 to 1 (oxazepam to diazepam), 1 to 3 (diazepam to oxazepam) as the ratio (3:1 and 1:3), so 15 mg of oxazepam would equate to 5 mg of diazepam.[34]

Chemistry

[edit]Oxazepam exists as a racemic mixture.[35] Early attempts to isolate enantiomers were unsuccessful; the corresponding acetate has been isolated as a single enantiomer. Given the different rates of epimerization that occur at different pH levels, it was determined that there would be no therapeutic benefit to the administration of a single enantiomer over the racemic mixture.[36]

Frequency of use

[edit]Oxazepam, along with diazepam, nitrazepam, and temazepam, were the four benzodiazepines listed on the pharmaceutical benefits scheme and represented 82% of the benzodiazepine prescriptions in Australia in 1990–1991.[37] It is in several countries the benzodiazepine of choice for novice users, due to a low chance of accumulation and a relatively slow absorption speed.[38]

Society and culture

[edit]Misuse

[edit]Oxazepam has the potential for misuse, defined as taking the drug to achieve a high, or continuing to take the drug in the long term against medical advice.[39] Benzodiazepines, including diazepam, oxazepam, nitrazepam, and flunitrazepam, accounted for the largest volume of forged drug prescriptions in Sweden from 1982 to 1986. During this time, a total of 52% of drug forgeries were for benzodiazepines, suggesting they were a major prescription drug class of abuse.[40]

However, due to its slow rate of absorption and its slow onset of action,[30] oxazepam has a relatively low potential for abuse compared to some other benzodiazepines, such as temazepam, flunitrazepam, or triazolam. This is similar to the varied potential for abuse between different drugs of the barbiturate class.[41]

Legal status

[edit]Oxazepam is a Schedule IV drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[42]

Brand names

[edit]It is marketed under many brand names worldwide, including: Alepam, Alepan, Anoxa, Anxiolit, Comedormir, durazepam, Murelax, Nozepam, Oksazepam, Opamox, Ox-Pam, Oxa-CT, Oxabenz, Oxamin, Oxapam, Oxapax, Oxascand, Oxaze, Oxazepam, Oxazépam, Oxazin, Oxepam, Praxiten, Purata, Selars, Serax, Serepax, Seresta, Séresta, Serpax, Sobril, Tazepam, Vaben, and Youfei.[43]

It is also marketed in combination with hyoscine as Novalona and in combination with alanine as Pausafrent T.[43]

Environmental concerns

[edit]In 2013, a laboratory study which exposed European perch to oxazepam concentrations equivalent to those present in European rivers (1.8 μg/L) found that they exhibited increased activity, reduced sociality, and higher feeding rate.[44] In 2016, a follow-up study which exposed salmon smolt to oxazepam for seven days before letting them migrate observed increased intensity of migratory behaviour compared to controls.[45] A 2019 study associated this faster, bolder behaviour in exposed smolt to increased mortality due to a higher likelihood of being predated on.[46]

On the other hand, a 2018 study from the same authors, which kept 480 European perch and 12 northern pikes in 12 ponds over 70 days, half of them control and half spiked with oxazepam, found no significant difference in either perch growth or mortality. However, it suggested that the latter could be explained by the exposed perch and pike being equally hampered by oxazepam, rather than the lack of an overall effect.[47] Lastly, a 2021 study built on these results by comparing two whole lakes filled with perch and pikes - one control while the other was exposed to oxazepam 11 days into experiment, at concentrations between 11 and 24 μg/L, which is 200 times greater than the reported concentrations in the European rivers. Even so, there were no measurable effects on pike behaviour after the addition of oxazepam, while the effects on perch behaviour were found to be negligible. The authors concluded that the effects previously attributed to oxazepam were instead likely caused by a combination of fish being stressed by human handling and small aquaria, followed by being exposed to a novel environment.[48]

References

[edit]- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ Encadré 1. Anxiolytiques à demi-vie courte (< 20 heures) et sans métabolite actif par ordre alphabétique de DCI

- ^ a b Sonne J, Loft S, Døssing M, Vollmer-Larsen A, Olesen KL, Victor M, et al. (1988). "Bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of oxazepam". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 35 (4): 385–389. doi:10.1007/bf00561369. PMID 3197746. S2CID 31007311.

- ^ a b Sonne J, Boesgaard S, Poulsen HE, Loft S, Hansen JM, Døssing M, Andreasen F (November 1990). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oxazepam and metabolism of paracetamol in severe hypothyroidism". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 30 (5): 737–742. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb03844.x. PMC 1368175. PMID 2271373.

- ^ CID 4616 from PubChem

- ^ "Benzodiazepine Names". non-benzodiazepines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ^ "FASS". Läkemedelsindustriföreningens Service AB. Archived from the original on 2011-10-01. Retrieved 2011-02-03.

- ^ Janecek J, Vestre ND, Schiele BC, Zimmermann R (December 1966). "Oxazepam in the treatment of anxiety states: a controlled study". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 4 (3): 199–206. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(66)90007-0. PMID 20034170.

- ^ Sarris J, Scholey A, Schweitzer I, Bousman C, Laporte E, Ng C, et al. (May 2012). "The acute effects of kava and oxazepam on anxiety, mood, neurocognition; and genetic correlates: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study". Human Psychopharmacology. 27 (3): 262–269. doi:10.1002/hup.2216. PMID 22311378. S2CID 44801451.

- ^ "Oxazepam (IARC Summary & Evaluation, Volume 66, 1996)". IARC. Archived from the original on 2008-09-07. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ^ Mandrioli R, Mercolini L, Raggi MA (October 2008). "Benzodiazepine metabolism: an analytical perspective". Current Drug Metabolism. 9 (8): 827–844. doi:10.2174/138920008786049258. PMID 18855614. Archived from the original on 2009-03-17.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 536. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ Galanter M, Kleber HD (1 July 2008). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment (4th ed.). United States of America: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-58562-276-4.

- ^ "Serax (oxazepam)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- ^ "Oxazepam Uses, Side Effects & Warnings - Drugs.com". drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2009-06-04.

- ^ "FDA expands Boxed Warning to improve safe use of benzodiazepine drug". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 23 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ MacKinnon GL, Parker WA (1982). "Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome: a literature review and evaluation". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 9 (1): 19–33. doi:10.3109/00952998209002608. PMID 6133446.

- ^ Authier N, Balayssac D, Sautereau M, Zangarelli A, Courty P, Somogyi AA, et al. (November 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises. 67 (6): 408–413. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- ^ Kanto JH (May 1982). "Use of benzodiazepines during pregnancy, labour and lactation, with particular reference to pharmacokinetic considerations". Drugs. 23 (5): 354–380. doi:10.2165/00003495-198223050-00002. PMID 6124415. S2CID 27014006.

- ^ McElhatton PR (Nov–Dec 1994). "The effects of benzodiazepine use during pregnancy and lactation". Reproductive Toxicology. 8 (6): 461–475. Bibcode:1994RepTx...8..461M. doi:10.1016/0890-6238(94)90029-9. PMID 7881198.

- ^ Buckley NA, Dawson AH, Whyte IM, O'Connell DL (January 1995). "Relative toxicity of benzodiazepines in overdose". BMJ. 310 (6974): 219–221. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6974.219. PMC 2548618. PMID 7866122.

- ^ Gaudreault P, Guay J, Thivierge RL, Verdy I (1991). "Benzodiazepine poisoning. Clinical and pharmacological considerations and treatment". Drug Safety. 6 (4): 247–265. doi:10.2165/00002018-199106040-00003. PMID 1888441. S2CID 27619795.

- ^ Perry HE, Shannon MW (June 1996). "Diagnosis and management of opioid- and benzodiazepine-induced comatose overdose in children". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 8 (3): 243–247. doi:10.1097/00008480-199606000-00010. PMID 8814402. S2CID 43105029.

- ^ Busto U, Kaplan HL, Sellers EM (February 1980). "Benzodiazepine-associated emergencies in Toronto". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 137 (2): 224–227. doi:10.1176/ajp.137.2.224. PMID 6101526.

- ^ Skerritt JH, Johnston GA (May 1983). "Enhancement of GABA binding by benzodiazepines and related anxiolytics". European Journal of Pharmacology. 89 (3–4): 193–198. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(83)90494-6. PMID 6135616.

- ^ Oelschläger H (July 1989). "[Chemical and pharmacologic aspects of benzodiazepines]". Schweizerische Rundschau für Medizin Praxis = Revue Suisse de Médecine Praxis. 78 (27–28): 766–772. PMID 2570451.

- ^ https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2011-11/mama_troubles_comportement_encadre_1_anxiolitiques.pdf[full citation needed]

- ^ Christensen P, Lolk A, Gram LF, Kragh-Sørensen P (1992). "Benzodiazepine-induced sedation and cortisol suppression. A placebo-controlled comparison of oxazepam and nitrazepam in healthy male volunteers". Psychopharmacology. 106 (4): 511–516. doi:10.1007/BF02244823. PMID 1349754. S2CID 29331503.

- ^ a b Serfaty M, Masterton G (September 1993). "Fatal poisonings attributed to benzodiazepines in Britain during the 1980s". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (3): 386–393. doi:10.1192/bjp.163.3.386. PMID 8104653. S2CID 46001278.

- ^ Sabath LD (December 1975). "Current status of treatment of pneumonia". Southern Medical Journal. 68 (12): 1507–1511. doi:10.1097/00007611-197512000-00012. PMID 0792. S2CID 20789345.

- ^ Olive G, Dreux C (January 1977). "[Pharmacologic bases of use of benzodiazepines in peréinatal medicine]". Archives Françaises de Pédiatrie. 34 (1): 74–89. PMID 851373.

- ^ "benzo.org.uk : Benzodiazepine Equivalence Table".

- ^ "Benzodiazepine equivalent dosage converter". GlobalRPH. Retrieved 2019-09-21.

- ^ Aso Y, Yoshioka S, Shibazaki T, Uchiyama M (May 1988). "The kinetics of the racemization of oxazepam in aqueous solution". Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 36 (5): 1834–1840. doi:10.1248/cpb.36.1834. PMID 3203421.

- ^ Crossley RJ (1995). Chirality and Biological Activity of Drugs. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0849391408.

- ^ Mant A, Whicker SD, McManus P, Birkett DJ, Edmonds D, Dumbrell D (December 1993). "Benzodiazepine utilisation in Australia: report from a new pharmacoepidemiological database". Australian Journal of Public Health. 17 (4): 345–349. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.1993.tb00167.x. PMID 7911332.

- ^ "Oxazepam".

- ^ Griffiths RR, Johnson MW (2005). "Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 66 Suppl 9: 31–41. PMID 16336040.

- ^ Bergman U, Dahl-Puustinen ML (1989). "Use of prescription forgeries in a drug abuse surveillance network". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 36 (6): 621–623. doi:10.1007/BF00637747. PMID 2776820. S2CID 19770310.

- ^ Griffiths RR, Wolf B (August 1990). "Relative abuse liability of different benzodiazepines in drug abusers". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 10 (4): 237–243. doi:10.1097/00004714-199008000-00002. PMID 1981067. S2CID 28209526.

- ^ "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). Vienna Austria: International Narcotics Control Board. August 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2005-12-05. Retrieved 2005-11-19.

- ^ a b "Oxazepam - International Brand Names". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ Brodin T, Fick J, Jonsson M, Klaminder J (February 2013). "Dilute concentrations of a psychiatric drug alter behavior of fish from natural populations". Science. 339 (6121): 814–815. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..814B. doi:10.1126/science.1226850. PMID 23413353. S2CID 38518537.

- ^ Hellström G, Klaminder J, Finn F, Persson L, Alanärä A, Jonsson M, et al. (December 2016). "GABAergic anxiolytic drug in water increases migration behaviour in salmon". Nature Communications. 7 (13460): 13460. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713460H. doi:10.1038/ncomms13460. PMC 5155400. PMID 27922016.

- ^ Klaminder J, Jonsson M, Leander J, Fahlman J, Brodin T, Fick J, Hellström G (October 2019). "Less anxious salmon smolt become easy prey during downstream migration". The Science of the Total Environment. 687: 488–493. Bibcode:2019ScTEn.687..488K. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.488. PMID 31212157. S2CID 195065107.

- ^ Lagesson A, Brodin T, Fahlman J, Fick J, Jonsson M, Persson J, et al. (February 2018). "No evidence of increased growth or mortality in fish exposed to oxazepam in semi-natural ecosystems". The Science of the Total Environment. 615: 608–614. Bibcode:2018ScTEn.615..608L. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.070. PMID 28988097.

- ^ Fahlman J, Hellström G, Jonsson M, Fick JB, Rosvall M, Klaminder J (March 2021). "Impacts of Oxazepam on Perch (Perca fluviatilis) Behavior: Fish Familiarized to Lake Conditions Do Not Show Predicted Anti-anxiety Response". Environmental Science & Technology. 55 (6): 3624–3633. Bibcode:2021EnST...55.3624F. doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c05587. PMC 8031365. PMID 33663207.