Southampton

Southampton | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Gateway to the World | |

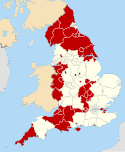

Shown within Hampshire | |

| Coordinates: 50°54′09″N 01°24′15″W / 50.90250°N 1.40417°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | England |

| Region | South East England |

| Ceremonial county | Hampshire |

| Settled | c. AD 43 |

| City status | 1964 |

| Unitary authority | 1997 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Unitary authority, city |

| • Governing body | Southampton City Council |

| • Leadership | Leader & cabinet |

| • Council control | Labour |

| • Members of Parliament | |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 28.1 sq mi (72.8 km2) |

| Population | |

• City and unitary authority area | 269,781 |

• Estimate (2017) | 252,400 (Council area) |

| • Density | 13,120/sq mi (5,066/km2) |

| • Urban | 855,569 |

| • Metro | 1,547,000 (South Hampshire)[1] |

| Demonym | Sotonian |

| Ethnicity (2021) | |

| • Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2021) | |

| • Religion | List

|

| Time zone | UTC+0 (Greenwich Mean Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (British Summer Time) |

| Postcode span | |

| Area code | 023 8 |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-STH |

| GDP | US$ 51.6 billion[5] |

| GDP per capita | US$ 37,832[5] |

| GVA | 2013 |

| • Total | £9.7 bn ($15.7 bn) (12th) |

| • Growth | |

| • Per capita | £21,400 ($34,300) (15th) |

| • Growth | |

| Grid ref. | SU 42 11 |

| ONS code | 00MS (ONS) E06000045 (GSS) |

| Police | Hampshire and Isle of Wight |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| Fire | Hampshire and Isle of Wight |

| Website | southampton |

Southampton (/saʊθˈ(h)æmptən/ ⓘ) is a port city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately 80 miles (130 km) southwest of London, 20 miles (32 km) west of Portsmouth, and 20 miles (32 km) southeast of Salisbury.[6][7] Southampton had a population of 253,651 at the 2011 census, making it one of the most populous cities in southern England.[2]

Southampton forms part of the larger South Hampshire conurbation which includes the city of Portsmouth and the boroughs of Havant, Eastleigh, Fareham and Gosport. A major port,[8] and close to the New Forest, Southampton lies at the northernmost point of Southampton Water, at the confluence of the River Test and Itchen,[9] with the River Hamble joining to the south. Southampton is classified as a Medium-Port City.[10]

Southampton was the departure point for the RMS Titanic[11] and home to 500 of the people who perished on board.[12] The Spitfire was built in the city[13] and Southampton has a strong association with the Mayflower, being the departure point before the vessel was forced to return to Plymouth. In the past century the city was one of Europe's main ports for ocean liners. More recently, Southampton is known as the home port of some of the largest cruise ships in the world.[14] The Cunard Line maintains a regular transatlantic service to New York from the city. Southampton is also one of the largest retail destinations in the South of England.[15]

Southampton was heavily bombed during the Second World War during what was known as the Southampton Blitz. It was one of the major embarkation points for D-Day. In the Middle Ages Southampton was where troops left England for the Battle of Agincourt. It was itself raided by French pirates, leading to the construction of the fortified town walls, many of which still stand today. Jane Austen also lived in Southampton for a number of years. In 1964, the town of Southampton acquired city status, becoming the City of Southampton.[16]

Some notable employers in the city include the University of Southampton, Ordnance Survey, BBC South, Associated British Ports, and Carnival UK.[17]

History

[edit]Pre-Norman

[edit]Archaeological finds suggest that the area has been inhabited since the Stone Age.[18] Following the Roman invasion of Britain in AD 43 and the conquering of the local Britons in AD 70 the fortress settlement of Clausentum was established. It was an important trading port and defensive outpost of Winchester, at the site of modern Bitterne Manor. Clausentum was defended by a wall and two ditches and is thought to have contained a bath house.[19] Clausentum was not abandoned until around 410.[18]

The Anglo-Saxons formed a new, larger, settlement across the Itchen centred on what is now the St Mary's area of the city. The settlement was known as Hamwic,[18] which evolved into Hamtun and then Hampton.[20] Archaeological excavations of this site have uncovered one of the best collections of Saxon artefacts in Europe.[18] It is from this town that the county of Hampshire gets its name.

Viking raids from 840 onwards contributed to the decline of Hamwic in the 9th century,[21] and by the 10th century a fortified settlement, which became medieval Southampton, had been established.[22]

11th–13th centuries

[edit]Following the Norman Conquest in 1066, Southampton became the major port of transit between the then capital of England, Winchester, and Normandy. Southampton Castle was built in the 12th century[16] and surviving remains of 12th-century merchants' houses such as King John's House and Canute's Palace are evidence of the wealth that existed in the town at this time.[23] By the 13th century Southampton had become a leading port, particularly involved in the import of French wine[22] in exchange for English cloth and wool.[24]

The Franciscan friary in Southampton was founded circa 1233.[25] The friars constructed a water supply system in 1290, which carried water from Conduit Head (remnants of which survive near Hill Lane, Shirley) some 1.1 mi (1.7 km) to the site of the friary inside the town walls.[26][verification needed] Further remains can be observed at Conduit House on Commercial Road. The friars granted use of the water to the town in 1310.[26]

14th century

[edit]Between 1327 and 1330, the King and Council received a petition from the people of Southampton. The community of Southampton claimed that Robert Batail of Winchelsea and other men of the Cinque Ports came to Southampton under the pretence that they were a part of Thomas of Lancaster's rebellion against Edward II. The community thought that they were in conspiracy with Hugh le Despenser the Younger. The petition states that, the supposed rebels in the Despenser War 'came to Southampton harbour, and burnt their ships, and their goods, chattels and merchandise which was in them, and carried off other goods, chattels and merchandise of theirs found there, and took some of the ships with them, to a loss to them of £8000 and more.'[27] For their petition to the King somewhere after 1321 and before 1327 earned some of the people of Southampton a prison sentence at Portchester Castle, possibly for insinuating the king's advisor Hugh le Despenser the Younger acted in conspiracy with the Cinque Port men to damage Southampton, a flourishing port in the fourteenth century. When King Edward III came to the throne, this petition was given to the king and his mother, Queen Isabella, who was in charge of the town, and the country at this stage likely organised the writ of trespass that took any guilt away from the community at Southampton.

The town was sacked in 1338 by French, Genoese and Monegasque ships (under Charles Grimaldi, who used the plunder to help found the principality of Monaco).[28] On visiting Southampton in 1339, Edward III ordered that walls be built to "close the town". The extensive rebuilding — part of the walls dates from 1175 — culminated in the completion of the western walls in 1380.[29][30] Roughly half of the walls, 13 of the original towers, and six gates survive.[29]

In 1348, the Black Death reached England via merchant vessels calling at Southampton.[31]

15th century

[edit]Prior to King Henry's departure for the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, the ringleaders of the "Southampton Plot"—Richard, Earl of Cambridge, Henry Scrope, 3rd Baron Scrope of Masham, and Sir Thomas Grey of Heton—were accused of high treason and tried at what is now the Red Lion public house in the High Street.[32][dubious – discuss] They were found guilty and summarily executed outside the Bargate.[33]

The city walls include God's House Tower, built in 1417, the first purpose-built artillery fortification in England.[34] Over the years it has been used as home to the city's gunner, the Town Gaol and even as storage for the Southampton Harbour Board.[30] Until September 2011, it housed the Museum of Archaeology.[35] The walls were completed in the 15th century,[22] but later development of several new fortifications along Southampton Water and the Solent by Henry VIII meant that Southampton was no longer dependent upon its own fortifications.[36]

During the Middle Ages, shipbuilding had become an important industry for the town. Henry V's famous warship Grace Dieu was built in Southampton and launched in 1418.[16]

The friars passed on ownership of the water supply system itself to the town in 1420.[26]

On the other hand, many of the medieval buildings once situated within the town walls are now in ruins or have disappeared altogether. From successive incarnations of the motte and bailey castle, only a section of the bailey wall remains today, lying just off Castle Way.[37]

In 1447 Henry VI granted Southampton a charter which made it a county of itself, separate for most purposes from the county of Hampshire. The town was granted its own sheriff, which it retains to this day.[38]

16th–18th centuries

[edit]The friary was dissolved in 1538 but its ruins remained until they were swept away in the 1940s.[25]

The port was the point of departure for the Pilgrim Fathers aboard Mayflower in 1620.[29] In 1642, during the English Civil War, a Parliamentary garrison moved into Southampton.[39] The Royalists advanced as far as Redbridge in March 1644 but were prevented from taking the town.[39]

Southampton became a spa town in 1740.[40] It had also become a popular site for sea bathing by the 1760s, despite the lack of a good quality beach.[40] Innovative buildings specifically for this purpose were built at West Quay, with baths that were filled and emptied by the flow of the tide.[40] Southampton engineer Walter Taylor's 18th-century mechanisation of the block-making process was a significant step in the Industrial Revolution.[41] The port was used for military embarkation, including during 18th-century wars with the French.[42]

19th century

[edit]The town experienced major expansion during the Victorian era.[16] The Southampton Docks company had been formed in 1835.[16] In October 1838 the foundation stone of the docks was laid[16] and the first dock opened in 1842.[16] The structural and economic development of docks continued for the next few decades.[16] The railway link to London was fully opened in May 1840.[16] Southampton subsequently became known as The Gateway to the Empire.[43]

In his 1854 book The Cruise of the Steam Yacht North Star John Choules described Southampton thus: "I hardly know a town that can show a more beautiful Main Street than Southampton, except it be Oxford. The High Street opens from the quay, and under various names it winds in a gently sweeping line for one mile and a half, and is of very handsome width. The variety of style and color of material in the buildings affords an exhibition of outline, light and colour, that I think is seldom equalled. The shops are very elegant, and the streets are kept exceedingly clean."

The port was used for military embarkation, including the Crimean War[44] and the Boer War.[45]

A new pier, with ten landing stages, was opened by the Duke of Connaught on 2 June 1892.[38] The Grand Theatre opened in 1898. It was demolished in 1960.[46]

20th century

[edit]

From 1904 to 2004, the Thornycroft shipbuilding yard was a major employer in Southampton,[16] building and repairing ships used in the two World Wars.[16] In 1912, the RMS Titanic sailed from Southampton. 497 men (four in five of the crew on board the vessel) were Sotonians,[47] with about a third of those who perished in the tragedy hailing from the city.[29] Today, visitors can see the Titanic Engineers' Memorial in East Park, built in 1914, dedicated to the ship's engineers who died on board. Nearby is another Titanic memorial, commemorating the ship's musicians.

Southampton subsequently became the home port for the transatlantic passenger services operated by Cunard with their Blue Riband liner RMS Queen Mary and her running mate RMS Queen Elizabeth. In 1938, Southampton docks also became home to the flying boats of Imperial Airways.[16] Southampton Container Terminals first opened in 1968[16] and has continued to expand.

Southampton was designated No. 1 Military Embarkation port during World War I[16] and became a major centre for treating the returning wounded and POWs.[16] It was also central to the preparations for the Invasion of Europe during World War II in 1944.[16]

The Supermarine Spitfire was designed and developed in Southampton, evolving from the Schneider trophy-winning seaplanes of the 1920s and 1930s. Its designer, R J Mitchell, lived in the Portswood area of Southampton, and his house is today marked with a blue plaque.[48] Heavy bombing of the Woolston factory in September 1940 destroyed it as well as homes in the vicinity, killing civilians and workers. World War II hit Southampton particularly hard because of its strategic importance as a major commercial port and industrial area. Prior to the Invasion of Europe, components for a Mulberry harbour were built here.[16] After D-Day, Southampton docks handled military cargo to help keep the Allied forces supplied,[16] making it a key target of Luftwaffe bombing raids until late 1944.[49] Southampton docks was featured in the television show 24: Live Another Day in Day 9: 9:00 p.m. – 10:00 p.m.[50]

Some 630 people died as a result of the air raids on Southampton and nearly 2,000 more were injured, not to mention the thousands of buildings damaged or destroyed.[51] Pockets of Georgian architecture survived the war, but much of the city was levelled. There has been extensive redevelopment since World War II.[16] Increasing traffic congestion in the 1920s led to partial demolition of medieval walls around the Bargate in 1932 and 1938.[16] However, a large portion of those walls remain.

A Royal Charter in 1952 upgraded University College at Highfield to the University of Southampton.[16] In 1964 Southampton acquired city status, becoming the City of Southampton,[16] and because of the Local Government Act 1972 was turned into a non-metropolitan district within Hampshire in 1973.

Southampton City Council took over most of the functions of Hampshire County Council within the city in April 1997 (including education and social services, but not the fire service), and thus became a unitary authority.[52]

21st century

[edit]In the 2010s several developments to the inner-city of Southampton were completed. In 2016 the south section of West Quay, or West Quay South, originally known as West Quay Watermark, was opened to the public. Its public plaza has been used for several annual events, such as an ice skating rink during the winter season,[53] and a public broadcast of the Wimbledon tennis championship.[54] Two new buildings, the John Hansard Gallery with City Eye and a secondary site for the University of Southampton's Nuffield Theatre, in addition to several flats, were built in the "cultural quarter" adjacent to Guildhall Square in 2017.[55]

Governance

[edit]

After the establishment of Hampshire County Council, following the passage of the 1888 Local Government Act, Southampton became a county borough within the county of Hampshire, which meant that the Corporation in Southampton had the combined powers of a lower-tier (borough) and an upper-tier (county) council within the city boundaries, while the new county council was responsible for upper-tier functions outside the city of Southampton. The ancient shire county, along with its associated assizes, was known as the County of Southampton[56] or Southamptonshire.[57] This was officially changed to Hampshire in 1959, although the county had been commonly known as Hampshire (and previously Hantescire – the origin of the abbreviation "Hants.") for centuries. In the reorganisation of English and Welsh local government that took effect on 1 April 1974, Southampton lost its county borough when it became a non-metropolitan district (i.e. with lower-tier local government functions only) within a modified non-metropolitan county of Hampshire (Bournemouth and Christchurch were transferred to the neighbouring non-metropolitan county of Dorset). From this date, Hampshire County Council became responsible for all upper-tier functions within its boundaries, including Southampton, until local government was once again reorganised in the late 1990s.

Southampton as a port and city has had a long history of administrative independence of the surrounding County; as far back as the reign of King John the town and its port were removed from the writ of the King's Sheriff in Hampshire and the rights of custom and toll were granted by the King to the burgesses of Southampton over the port of Southampton and the Port of Portsmouth;[58] this tax farm was granted for an annual fee of £200 in the charter dated at Orival on 29 June 1199. The definition of the port of Southampton was apparently broader than today and embraced all of the area between Lymington and Langstone. The corporation had resident representatives in Newport, Lymington and Portsmouth.[59] By a charter of Henry VI, granted on 9 March 1446/7 (25+26 Hen. VI, m. 52), the mayor, bailiffs and burgesses of the towns and ports of Southampton and Portsmouth became a County incorporate and separate from Hampshire. The status of the town was changed by a later charter of Charles I by at once the formal separation from Portsmouth and the recognition of Southampton as a county. The formal title of the town became "The Town and County of the Town of Southampton".[citation needed] These charters and Royal Grants, of which there were many, also set out the governance and regulation of the town and port which remained the "constitution" of the town until the local government organisation of the later Victorian period when the Local Government Act 1888 set up County Councils and County Borough Councils across England and Wales, including Southampton County Borough Council. Under this regime, "The Town and County of the Town of Southampton" became a county borough with responsibility for all aspects of local government. On 24 February 1964 Elizabeth II, by Letters Patent, granted the County Borough of Southampton the title of "City", so creating "The City and County of the City of Southampton".[60] This did not, however, affect its composition or powers.

The city has undergone many changes to its governance over the centuries and once again became administratively independent from Hampshire County as it was made into a unitary authority in a local government reorganisation on 1 April 1997, a result of the 1992 Local Government Act. The district remains part of the Hampshire ceremonial county.

Southampton City Council consists of 51 councillors, 3 for each of the 17 wards. Council elections are held in early May for one third of the seats (one councillor for each ward), elected for a four-year term, so there are elections three years out of four. The Labour Party has held overall control since 2022; after the 2023 council elections the composition of the council is:

| Party | Members | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour | 35 | |

| Conservative | 9 | |

| Liberal Democrat | 3 | |

| Green | 1 | |

| Total | 51[61] | |

There are three members of Parliament for the city: Darren Paffey (Labour) for Southampton Itchen, the constituency covering the east of the city; Satvir Kaur (Labour) for Southampton Test, which covers the west of the city; and Caroline Nokes (Conservative) for Romsey and Southampton North, which includes a northern portion of the city.

Mayor and sheriff

[edit]The first mayor of Southampton served in 1222 meaning 2022 was the 800th anniversary of the office.

Early mayors of Southampton include:

- 1386–89, 1390–91, and 1396–97: William Maple[62]

- 1393–94, 1407–08, Walter Lange[63]

The first female mayor was Lucia Foster Welch, elected in 1927.[64] In 1959 the city elected its sixth female mayor, Rosina Marie Stonehouse, mother to John Stonehouse.[65]

The current mayor of Southampton is Councillor David Shields[66]

Southampton is one of 16 cities and towns in England and Wales to have a ceremonial sheriff who acts as a deputy for the mayor. Traditionally the sheriff serves for one year after, which they will become the mayor of Southampton.

Southampton's submission of an application for Lord Mayor status, as part of Queen Elizabeth II's Platinum Jubilee Civic Honours Competition 2022, was successful.[67] Once the Letters Patent were published, the current Mayor (Councillor Jaqui Rayment) became the first Lord Mayor of Southampton. The Princess Royal presented the Lord Mayor with the Letters Patent in February 2023.[68]

Town crier

[edit]The town crier from 2004 until his death in 2014 was John Melody, who acted as master of ceremonies in the city and who possessed a cry of 104 decibels.[69] Southampton's current Town Crier is Alan Spencer[70]

Twinned towns

[edit]Southampton City Council has developed twinning links with Le Havre in France (since 1973),[71][72][73][74] Rems-Murr-Kreis in Germany (since 1991),[73] Trieste in Italy (since 2002), Hampton, Virginia, in the US,[75][76][77] Qingdao in China (since 1998),[73] Busan in South Korea (since 1978),[78] and Miami, Florida, also in the US (since 14 June 2019).[79]

Geography

[edit]The geography of Southampton is influenced by the sea and rivers. The city lies at the northern tip of the Southampton Water, a deep water estuary, which is a ria formed at the end of the last Ice Age and which opens into The Solent. At the head of Southampton Water the rivers Test and Itchen converge.[80] The Test — which has a salt marsh that makes it ideal for salmon fishing[81] — runs along the western edge of the city, while the Itchen splits Southampton in two—east and west. The city centre is located between the two rivers.

Town Quay is the original public quay, and dates from the 13th century. Today's Eastern Docks were created in the 1830s by land reclamation of the mud flats between the Itchen and Test estuaries. The Western Docks date from the 1930s when the Southern Railway Company commissioned a major land reclamation and dredging programme.[82] Most of the material used for reclamation came from dredging of Southampton Water,[83] to ensure that the port can continue to handle large ships.

Southampton Water has the benefit of a double high tide, with two high tide peaks,[84] making the movement of large ships easier.[85] This is not caused as popularly supposed by the presence of the Isle of Wight, but is a function of the shape and depth of the English Channel. In this area the general water flow is distorted by more local conditions reaching across to France.[86]

The city lies in the Hampshire Basin, which sits atop chalk beds.[80]

The River Test runs along the western border of the city, separating it from the New Forest. There are bridges over the Test from Southampton, including the road and rail bridges at Redbridge in the south and the M27 motorway to the north. The River Itchen runs through the middle of the city and is bridged in several places. The northernmost bridge, and the first to be built,[87] is at Mansbridge, where the A27 road crosses the Itchen. The original bridge is closed to road traffic, but is still standing and open to pedestrians and cyclists. The river is bridged again at Swaythling, where Woodmill Bridge separates the tidal and non tidal sections of the river. Further south is Cobden Bridge which is notable as it was opened as a free bridge (it was originally named the Cobden Free Bridge), and was never a toll bridge. Downstream of the Cobden Bridge is the Northam Railway Bridge, then the Northam Road Bridge, which was the first major pre-stressed concrete bridge to be constructed in the United Kingdom.[88] The southernmost, and newest, bridge on the Itchen is the Itchen Bridge, which is a toll bridge.

Areas and suburbs

[edit]Southampton is divided into council wards, suburbs, constituencies, ecclesiastical parishes, and other less formal areas. It has a number of parks and green spaces, the largest being the 148-hectare Southampton Common,[89] parts of which are used to host the annual summer festivals, circuses and fun fairs. The Common includes Hawthorns Urban Wildlife Centre[90] on the former site of Southampton Zoo, a paddling pool and several lakes and ponds. The common also hosts the Parkrun event every Saturday.[91]

Council estates are in the Weston, Thornhill and Townhill Park districts. The city is ranked 96th most deprived out of all 354 Local Authorities in England.[92]

In 2006–2007, 1,267 residential dwellings were built in the city — the highest number for 15 years. Over 94 per cent of these were flats.[93]

There are 16 Electoral Wards in Southampton, each consisting of longer-established neighbourhoods (see below).

Settlements outside the city are sometimes considered suburbs of Southampton, including Chartwell Green, Chilworth, Nursling, Rownhams, Totton, Eastleigh and West End. The villages of Marchwood, Ashurst and Hedge End may be considered exurbs of Southampton.

Climate

[edit]As with the rest of the UK, Southampton experiences an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb). Its southerly, low-lying and sheltered location ensures it is among the warmer, sunnier cities in the UK. It has held the record for the highest temperature in the UK for June at 35.6 °C (96.1 °F) since 1976.[94][95]

| Climate data for Southampton (Mayflower Park), elevation: 19 m (62 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1853–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.9 (60.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

27.6 (81.7) |

31.7 (89.1) |

35.6 (96.1) |

34.8 (94.6) |

35.1 (95.2) |

30.6 (87.1) |

28.9 (84.0) |

18.3 (64.9) |

15.9 (60.6) |

35.6 (96.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) |

9.1 (48.4) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.7 (58.5) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.6 (69.1) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

20.1 (68.2) |

15.9 (60.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

9.3 (48.7) |

15.4 (59.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

3.0 (37.4) |

4.3 (39.7) |

6.1 (43.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

13.9 (57.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.6 (52.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.7 (42.3) |

3.5 (38.3) |

8.0 (46.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.6 (2.1) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

1.8 (35.2) |

5.6 (42.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−8.7 (16.3) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−16.6 (2.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 89.7 (3.53) |

63.9 (2.52) |

56.0 (2.20) |

52.3 (2.06) |

47.4 (1.87) |

56.9 (2.24) |

44.0 (1.73) |

58.9 (2.32) |

60.5 (2.38) |

92.6 (3.65) |

99.9 (3.93) |

96.9 (3.81) |

818.6 (32.23) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 12.5 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 11.8 | 12.8 | 12.7 | 119.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 63.4 | 82.7 | 125.1 | 181.6 | 215.5 | 211.7 | 223.8 | 205.8 | 152.0 | 112.7 | 76.3 | 55.3 | 1,705.7 |

| Source 1: Met Office[96] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: KNMI[97] | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9.5 °C (49.1 °F) | 9.0 °C (48.2 °F) | 8.6 °C (47.5 °F) | 9.8 °C (49.6 °F) | 11.4 °C (52.5 °F) | 13.5 °C (56.3 °F) | 15.3 °C (59.5 °F) | 16.8 °C (62.2 °F) | 17.3 °C (63.1 °F) | 16.2 °C (61.2 °F) | 14.4 °C (57.9 °F) | 11.8 °C (53.2 °F) | 12.8 °C (55.0 °F) |

Energy

[edit]

The centre of Southampton is located above a large hot water aquifer that provides geothermal power to some of the city's buildings. This energy is processed at a plant in the West Quay region in Southampton city centre, the only geothermal power station in the UK. The plant provides electricity for the Port of Southampton and hot water to the Southampton District Energy Scheme used by many buildings including the Westquay shopping centre. In a 2006 survey of carbon emissions in major UK cities conducted by British Gas, Southampton was ranked as being one of the lowest carbon-emitting cities in the United Kingdom.[99]

Demographics

[edit]

2016 mid-year population estimates suggests there are 254,275 people within the Southampton area.[3] At the 2011 Census, the Southampton built-up area (which is a little larger than the area controlled by the city council) had a population of 253,651.[2] There were 127,630 males and 126,021 females.[2] The 30–44 age range is the most populous, with 51,989 people falling in this age range. Next largest is the 45–59 range with 42,317 people and then 20–24 years with 30,290.[2] The ethnic mix is 86.4% white, 8.1% were Asian or British Asian, 2.0% black, 1.1% other ethnic groups, and 2.3% were multi-ethnic.[2]

Between 1996 and 2004, the population of the city increased by 4.9 per cent — the tenth-biggest increase in England.[100] In 2005 the Government Statistics stated that Southampton was the third most densely populated city in the country after London and Portsmouth, respectively.[101] The average age of a Sotonian was 37.6 years in 2016, ranking Southampton as one of the twenty most youthful cities in the UK.[102]

In the 2001 census Southampton and Portsmouth were recorded as being parts of separate urban areas; however by the time of the 2011 census they had merged apolitically to become the sixth-largest built-up area in England with a population of 855,569.[who?] This built-up area is part of the metropolitan area known as South Hampshire, which is also sometimes referred to as Solent City, particularly in the media when discussing development issues and local governance organisational changes.[103][104][105] With a population of over 1.5 million this makes the region one of the United Kingdom's most populous metropolitan areas.[1]

Ethnicity

[edit]| Ethnic group | 1981 estimations[106] | 1991[107] | 2001[108] | 2011[109] | 2021[110] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| White: Total | 190,563 | 95.7% | 187,170 | 95.1% | 200,859 | 92.4% | 203,528 | 85.9% | 200,829 | 80.7% |

| White: British | – | – | – | – | 192,970 | 88.7% | 183,980 | 77.7% | 169,481 | 68.1% |

| White: Irish | – | – | – | – | 2,298 | 1,746 | 1643 | 0.7% | ||

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller | – | – | – | – | – | – | 341 | 340 | 0.1% | |

| White: Roma | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 578 | 0.2% |

| White: Other | – | – | – | – | 5,591 | 2.6% | 17,461 | 28,787 | 11.6% | |

| Asian or Asian British: Total | – | – | 6,724 | 3.4% | 9,887 | 4.5% | 19,892 | 8.4% | 26,414 | 10.6% |

| Asian or Asian British: Indian | – | – | 3,863 | 4,717 | 6,742 | 9,169 | 3.7% | |||

| Asian or Asian British: Pakistani | – | – | 993 | 1,743 | 3,019 | 4,248 | 1.7% | |||

| Asian or Asian British: Bangladeshi | – | – | 515 | 961 | 1,401 | 2,064 | 0.8% | |||

| Asian or Asian British: Chinese | – | – | 698 | 1,633 | 3,449 | 4,149 | 1.7% | |||

| Asian or Asian British: Other Asian | – | – | 655 | 833 | 5,281 | 6,784 | 2.7% | |||

| Black or Black British: Total | – | – | 1,741 | 0.9% | 2,245 | 1% | 5,067 | 2.1% | 7,539 | 3% |

| Black or Black British: Caribbean | – | – | 830 | 1,034 | 1,132 | 5,627 | 2.3% | |||

| Black or Black British: African | – | – | 331 | 1,054 | 3,508 | 1,103 | 0.4% | |||

| Black or Black British: Other Black | – | – | 580 | 157 | 427 | 809 | 0.3% | |||

| Mixed or British Mixed: Total | – | – | – | – | 3,267 | 1.5% | 5,678 | 2.4% | 8,309 | 3.4% |

| Mixed: White and Black Caribbean | – | – | – | – | 1,010 | 1,678 | 2,173 | 0.9% | ||

| Mixed: White and Black African | – | – | – | – | 480 | 941 | 1,535 | 0.6% | ||

| Mixed: White and Asian | – | – | – | – | 1,061 | 1,796 | 2,444 | 1.0% | ||

| Mixed: Other Mixed | – | – | – | – | 716 | 1,263 | 2,157 | 0.9% | ||

| Other: Total | – | – | 1,229 | 0.6% | 1,187 | 0.5% | 2,717 | 1.1% | 5,829 | 2.3% |

| Other: Arab | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1,312 | 1,311 | 0.5% | |

| Other: Any other ethnic group | – | – | 1,229 | 1,187 | 1,405 | 4,518 | 1.8% | |||

| Non-White: Total | 8,566 | 4.3% | 9,694 | 4.9% | 16,586 | 7.6% | 33,354 | 14.1% | 48,091 | 19.3% |

| Total | 199,129 | 100% | 196,864 | 100% | 217,445 | 100% | 236,882 | 100% | 248,920 | 100% |

Religion

[edit]| Religion | 2001[111] | 2011[112] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| Holds religious beliefs | 153,014 | 70.2 | 140,793 | 59.4 |

| 142,531 | 65.5 | 122,018 | 51.5 | |

| 712 | 0.3 | 1,331 | 0.6 | |

| 1,535 | 0.7 | 2,482 | 1.0 | |

| 293 | 0.1 | 254 | 0.1 | |

| 4,185 | 1.9 | 9,903 | 4.2 | |

| 2,799 | 1.3 | 3,476 | 1.5 | |

| Other religion | 959 | 0.4 | 1,329 | 0.6 |

| (No religion and Religion not stated) | 64,431 | 29.6 | 96,089 | 40.6 |

| No religion | 47,004 | 21.6 | 79,379 | 33.5 |

| Religion not stated | 17,427 | 8.0 | 16,710 | 7.1 |

| Total population | 217,445 | 100.0 | 236,882 | 100.0 |

Economy

[edit]| Sector | 2000 | 2004 | 2008 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture[113] | £1m | £3m | £1m | £1m |

| Business[114] | £532m | £685m | £736m | £638m |

| Construction[115] | £205m | £269m | £253m | £257m |

| Distribution[116] | £1,088m | £1,049m | £1,021m | £849m |

| Finance[117] | £342m | £397m | £548m | £459m |

In 2016–17, 169,700 residents of Southampton aged 16–64 were in employment, representing a rate of 71.4% – lower than the national rate of 74.4%. 6,600 were unemployed, representing 5% of the economically active population.[118]

In 2016–17, 24.8% of the city's resident population aged 16–64 were classed as economically inactive, higher than the national rate of 21.8%, although for over 40% of this group the reason was that they were students.[118]

Just over a quarter of the jobs available in the city are in the health and education sector. A further 19 per cent are property and other business and the third-largest sector is wholesale and retail, which accounts for 16.2 per cent.[119] Between 1995 and 2004, the number of jobs in Southampton has increased by 18.5 per cent.[100]

In January 2007, the average annual salary in the city was £22,267. This was £1,700 lower than the national average and £3,800 less than the average for the South East.[120]

Southampton has always been a port, and the docks have long been a major employer in the city. In particular, it is a port for cruise ships; its heyday was the first half of the 20th century, and in particular the inter-war years, when it handled almost half the passenger traffic of the UK. Today it remains home to luxury cruise ships, as well as being the largest freight port on the Channel coast and fourth-largest UK port by tonnage,[121] with several container terminals. Unlike some other ports, such as Liverpool, London, and Bristol, where industry and docks have largely moved out of the city centres leaving room for redevelopment, Southampton retains much of its inner-city industry. Despite the still-active and expanding docklands to the west of the city centre, further enhanced with the opening of a fourth cruise terminal in 2009, parts of the eastern docks have been redeveloped; the Ocean Village development, which included a local marina and small entertainment complex, is a good example. Southampton is home to the headquarters of both the Maritime and Coastguard Agency and the Marine Accident Investigation Branch of the Department for Transport in addition to cruise operator Carnival UK.[122][123]

During the 20th century, a more diverse range of industry also came to the city, including aircraft and car manufacturing, cables, electrical engineering products, and petrochemicals. These developed alongside the city's older industries of the docks, grain milling and tobacco processing.[9][124] Later changes saw the loss of Pirelli General cables and Joseph Rank's Solent Flour Mills.[125]

University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust is one of the city's largest employers. It provides local hospital services to 500,000 people in the Southampton area and specialist regional services to more than 3 million people across the South of England. The Trust owns and manages Southampton General Hospital, the Princess Anne Hospital and a palliative care service at Countess Mountbatten House, part of the Moorgreen Hospital site in the village of West End, just outside the city.

Other major employers in the city include Ordnance Survey, the UK's national mapping agency, whose headquarters is located in a new building on the outskirts of the city, opened in February 2011.[126] The Lloyd's Register Group has announced plans to move its London marine operations to a specially developed site at the University of Southampton.[127]

Southampton's largest retail centre, and 27th-largest in the UK, is the Westquay Shopping Centre, which opened in September 2000 and hosts major high street stores including John Lewis and Marks and Spencer. The centre was Phase Two of the West Quay development of the former Pirelli undersea cables factory; the first phase of this was the West Quay Retail Park, while the third phase, Watermark Westquay, was put on hold due to the recession. Work resumed in 2015, with plans for this third stage including shops, housing, an hotel and a public piazza alongside the Town Walls on Western Esplanade.[128] Southampton has also been granted a licence for a large casino.[129] A further part of the redevelopment of the West Quay site resulted in a new store, opened on 12 February 2009, for Swedish home products retailer IKEA.[130] Marlands is a smaller shopping centre, built in the 1990s on the site of the former bus station and located close to the northern side of Westquay. In October 2014, the city council approved a follow-up from the Westquay park, WestQuay Watermark. Construction by Sir Robert McAlpine commenced in January 2015.[131] Opened in 2016–2017, it has been renamed Westquay South.

In 2007, Southampton was ranked 13th for shopping in the UK.[132]

Southampton currently has three major city centre regeneration schemes under way. Construction on the £132m Bargate Quarter scheme, which is being built on the site of the former Bargate Centre, started in February 2022 and will provide over 500 new homes, new retail and hospitality venues and a new linear park running alongside the medieval town walls which is hoped to be completed by late 2024. A £200m redevelopment scheme opposite Southampton Central Railway Station is also planned and will replace the former Toys R Us store which is situated off Western Esplanade. The 4.8-acre (1.9 ha) Maritime Gateway scheme will have a new pedestrian-led public area with 600 new homes and new commercial space. Located close to the waterfront, Leisure World is Southampton's largest redevelopment project covering 13 acres (5.3 ha) and replacing the original Leisure World development which first opened in 1997. The £280m scheme will deliver 650 new homes, two hotels, a cinema, casino and catering outlets, with the first phase expected to complete by 2024/25.[citation needed]

PwC's Good Growth for Cities 2020 index places Southampton in the top three cities in England in terms of growth.[133] This strength has enabled the city to establish a reputation as a place to do business and has attracted nationally and internationally significant businesses.[clarification needed] Prior to the pandemic, Southampton's economy was valued at £8.3 billion GVA and in 2021 £7.84 billion. In 2022 GVA is forecast to recover to £8.2 billion. GVA growth was 10.6% in 2021 as the economy rebounded and growth returned. In 2022 GVA growth is forecast to be just over 5%.[citation needed]

Culture, media and sport

[edit]Culture

[edit]

The city is home to the longest surviving stretch of medieval walls in England,[134] as well as a number of museums such as Tudor House Museum, reopened on 30 July 2011 after undergoing extensive restoration and improvement; Southampton Maritime Museum;[135] God's House Tower, an archaeology museum about the city's heritage and located in one of the tower walls; the Medieval Merchant's House; and Solent Sky, which focuses on aviation.[136] The SeaCity Museum is located in the west wing of the civic centre, formerly occupied by Hampshire Constabulary and the Magistrates' Court, and focuses on Southampton's trading history and on the Titanic. The museum received half a million pounds from the National Lottery in addition to interest from numerous private investors and is budgeted at £28 million.

The annual Southampton Boat Show is held in September each year, with over 600 exhibitors present.[137] It runs for just over a week at Mayflower Park on the city's waterfront, where it has been held since 1968.[138] The Boat Show itself is the climax of Sea City, which runs from April to September each year to celebrate Southampton's links with the sea.[139]

The largest theatre in the city is the 2,300-capacity Mayflower Theatre (formerly known as the Gaumont), which, as the largest theatre in Southern England outside London, has hosted West End shows such as Les Misérables, The Rocky Horror Show and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, as well as regular visits from Welsh National Opera and English National Ballet. There is also the Nuffield Theatre[140] based at the University of Southampton's Highfield campus, which is the city's primary producing theatre. It was awarded The Stage Award for Best Regional Theatre in 2015.[141] It also hosts touring companies and local performing societies (such as Southampton Operatic Society, the Maskers and the University Players).

There are many innovative art galleries in the city. The Southampton City Art Gallery at the Civic Centre is one of the best known and as well as a nationally important Designated Collection, houses several permanent and travelling exhibitions. The Solent Showcase at Southampton Solent University, the John Hansard Gallery at Southampton University as well as smaller galleries including the Art House[142][better source needed] in Above Bar Street provide a different view.[143] The city's Bargate contains an art gallery run by the arts organisation "a space" who also run the Art Vaults project. This uses several of Southampton's medieval vaults, chambers, halls and cellars as venues for contemporary art installations.

In the heart of Southampton's city centre, you will find the Cultural Quarter, which has developed over recent years to become a rich and bustling arts space complete with a fusion of galleries, museums, theatres restaurants, bars, and cafés. The Cultural Quarter is home to the Southampton O2 Guildhall, MAST (Mayflower Studies), the John Hansard Gallery (Studio 144) and City Eye, the much-anticipated new arts centre for Southampton. It is also home to Southampton Art Gallery which first opened its doors in 1939 and offers the opportunity to enjoy national and international quality exhibitions ranging from painting, sculpture, and drawing, to photography and film, as well as permanent collection and displays. The gallery has a unique partnership with the National Gallery in London which, in 2021, was celebrated with an exhibition entitled “Creating a National Collection: The Partnership Between Southampton City Art Gallery and the National Gallery.”[144]

The Cultural Quarter's Guildhall Square often plays host to events and promotions such as Southampton Pride, Chinese New Year festivities, Seaside in the Square, Oktoberfest, Music in the city, Re:claim Street festival, the Southampton Slamma Skateboarding festival and it is also a start and finish area for the ABP Southampton Marathon, as well as it being the Southampton Remembrance Parade start and finish point.

Events in Southampton are generally promoted via the Visit Southampton website.

Shortlisted bid for UK City of Culture 2025

[edit]In October 2021, Southampton was longlisted for the UK City of Culture 2025.[145] The final bid, submitted on 2 February 2022 was marked by lighting The Bargate red with #MakeItSO projected across it. The city's bid includes plans to celebrate Southampton's people and places, its rich heritage and diversity, the world-class sports and venues, the parks and green spaces and food and drink. On 19 March 2022 it was announced that Southampton had made the short-list of four, alongside Bradford, County Durham, and Wrexham County Borough. In May 2022, it lost its bid, with the winner announced to be Bradford.[145]

Music

[edit]

Southampton has two large live music venues, the Mayflower Theatre (formerly the Gaumont Theatre) and the Guildhall. The Guildhall has seen concerts from a wide range of popular artists, including Pink Floyd,[146] David Bowie,[146] Delirious?,[147] Manic Street Preachers,[146] The Killers,[146] The Kaiser Chiefs,[146] Amy Winehouse, Bob Dylan, Suede, Arctic Monkeys, and Oasis.[146] It also hosts classical concerts presented by the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra,[148] City of Southampton Orchestra,[149] Southampton Concert Orchestra,[150] Southampton Philharmonic Choir,[151] Southampton Choral Society,[152] and the City of Southampton (Albion) Band.[citation needed]

The city also has several smaller music venues, including the Brook, Engine Rooms,[153] The 1865,[154] The Joiners,[155] and Turner Sims,[156] as well as smaller "club circuit" venues like Hampton's and Lennon's, and a number of public houses including the Platform tavern, the Dolphin, the Blue Keys and many others. The Joiners has played host to such acts as Oasis, Radiohead, Green Day, Suede, PJ Harvey, the Manic Street Preachers, Coldplay, the Verve, the Libertines, and Franz Ferdinand, while Hampton's and Lennon's have hosted early appearances by Kate Nash, Scouting for Girls, and Band of Skulls.

The city is home or birthplace to a number of contemporary musicians such as popstar Craig David, Coldplay drummer Will Champion, Alt-J singer Joe Newman, singer-songwriter Aqualung, former Holloways singer Rob Skipper, 1980s popstar Howard Jones, as well as Grammy Award-winning popstar Foxes. Several active rock and metal bands were formed in Southampton, including Band of Skulls, Bury Tomorrow, Creeper, and The Delays. Southampton had a prominent UK Garage scene, championed by the duo Artful Dodger, who formed in the city in the late 1990s,[157] as well as the UKG, grime and bassline producer, Royal-T, part of the TQD group formed with DJ Q and Flava D.[158] Notable bands who are now defunct include Thomas Tantrum (disbanded 2011), Kids Can't Fly (disbanded 2014), and Heart in Hand (disbanded 2015).

Media

[edit]Local media include the Southern Daily Echo newspaper based in Redbridge and BBC South, which has its regional headquarters in the city centre opposite the civic centre. From there the BBC broadcasts South Today, the local television news bulletin and BBC Radio Solent. The local ITV franchise is Meridian, which has its headquarters in Whiteley, around 9 mi (14 km) from the city. Until December 2004, the station's studios were located in the Northam area of the city on land reclaimed from the River Itchen. That's Solent is a local television channel that began broadcasting in November 2014, which will be based in and serve Southampton and Portsmouth.

Southampton also has four community FM radio stations, the Queens Award-winning Unity 101 Community Radio,[159] broadcasting full-time on 101.1 MHz since 2006 to the Asian and ethnic communities, and Voice FM,[160] located in St Mary's, which has been broadcasting full-time on 103.9 MHz since September 2011. A third station, Awaaz FM,[161] broadcasts on DAB digital to South Hampshire and on FM to Southampton. It caters for the Asian and ethnic community. The fourth community station is Fiesta FM and broadcasts on 95 MHz.

As of March 2023[update], the most popular commercial radio station is the adult contemporary regional radio station Wave 105 (13.7%), followed by the hit music station Capital South (2.4%) a networked station from London with local breakfast and drive shows. Other stations include Heart South (6.8%), Nation Radio South Coast (2.0%) and Easy Radio South Coast (0.3%).[162] In addition, Southampton University has a radio station called SURGE, broadcasting on AM band as well as through the web.

Sport

[edit]

Southampton is home to Southampton Football Club, nicknamed "The Saints" since 1885; the club currently plays in the Premier League at St Mary's Stadium, having relocated in 2001 from their 103-year-old former stadium, "The Dell". They reached the top flight of English football (First Division) for the first time in 1966, staying there for eight years. They lifted the FA Cup with a shock victory over Manchester United in 1976, returned to the top flight two years later, and stayed there for 27 years (becoming founder members of the Premier League in 1992) before they were relegated in 2005. The club was promoted back to the Premier League in 2012 following a brief spell in the third tier and severe financial difficulties. In 2015, "The Saints" finished 7th in the Premier League, their highest league finish in 30 years, after a remarkable season under new manager Ronald Koeman. Their highest league position came in 1984 when they were runners-up in the old First Division. They were also runners-up in the 1979 Football League Cup final and 2003 FA Cup final. Notable former managers include Ted Bates, Lawrie McMenemy, Chris Nicholl, Ian Branfoot and Gordon Strachan. There is a strong rivalry with Portsmouth F.C. ("South Coast derby") which is located only about 20 mi (30 km) away.

Southampton Women's F.C. won the inaugural Women's FA Cup in 1971 when they beat Stewarton Thistle 4-1 at Crystal Palace National Sports Centre. In total they won the tournament eight times between 1971 and 1981. A separate club called Red Star Southampton reached the final in 1992, losing 4-0 to Doncaster Belles, and their successors Southampton Saints lost the 1999 final to Arsenal before dissolving in 2019.[163] The current team Southampton F.C. Women play in the Women's Championship as of the 2024-25 season.[164]

The two local Sunday Leagues in the Southampton area are the City of Southampton Sunday Football League and the Southampton and District Sunday Football League.

Hampshire County Cricket Club play close to the city, at the Ageas Bowl in West End, after previously playing at the County Cricket Ground and the Antelope Ground, both near the city centre. The Southern Brave team of The Hundred also play at the Ageas Bowl, being the inaugural winners in the men's competition, and two time finalists in the women's.

The city also has a semi-professional basketball club, the Solent Kestrels. Founded in 1998 the team currently plays at the Solent Sports Complex, on the Solent University campus. They currently play in the NBL Division 1.

The city hockey club, Southampton Hockey Club, founded in 1938, is now one of the largest and highly regarded clubs in Hampshire, fielding 7 senior men's and 5 senior women's teams on a weekly basis along with boys' and girls' teams from 6 upwards.

The city is also well provided for in amateur men's and women's rugby with a number of teams in and around the city, the oldest of which is Trojans RFC,[165] which was promoted to London South West 2 division in 2008/9. A notable former player is Anthony Allen, who played with Leicester Tigers as a centre. Tottonians[166] are also in London South West division 2 and Southampton RFC[167] are in Hampshire division 1 in 2009/10, alongside Millbrook RFC[168] and Eastleigh RFC. Many of the sides run mini and midi teams from under sevens up to under sixteens for both boys and girls.

The city provides for yachting and water sports, with a number of marinas. From 1977 to 2001 the Whitbread Around the World Yacht Race, now the Volvo Ocean Race, was based in Southampton's Ocean Village marina.

Southampton Sports Centre is the focal point for the public's sporting and outdoor activities and includes an alpine centre with a dry ski slope, a theme park, and an athletics centre which is used by professional athletes Along with 11 other leisure venues which were formerly operated by the council leisure services, the operating rights have been sold to Park Wood Leisure.[169]

Southampton was named "fittest city in the UK" in 2006 by Men's Fitness magazine. The results were based on the incidence of heart disease, the amount of junk food and alcohol consumed, and the level of gym membership.[170] In 2007, it had slipped one place behind London, but was still ranked first when it came to the parks and green spaces available for exercise and the amount of television watched by Sotonians was the lowest in the country. Thousands enter and run the Southampton Marathon in April every year.[171] Speedway and racing took place at Banister Court Stadium in the pre-war era. It returned in the 1940s after WW2 and the Saints operated until the stadium closed down at the end of 1963. A training track operated in the 1950s in the Hamble area. Greyhound racing was also held at the stadium from 1928 to 1963.

Southampton is also home to two American football teams, the Solent Thrashers, who play at the Test Park Sports Ground, and the Southampton Stags, who play at the Wide Lane Sports Facility in Eastleigh.

The world's oldest surviving bowling green is the Southampton Old Bowling Green, which was first used in 1299.[172]

The city is home to two Octopush (also known as underwater hockey) clubs. Bournemouth and Southampton Octopush Club [173] and Totton Octopush Club.[174] Both clubs train at Totton Leisure Centre (with Bournemouth and Southampton OC also training in Ringwood). In the 2023 Nautilus Tournament, Bournemouth and Southampton OC finished 7th (out of 7) in Division 2 with Totton finishing 7th in Division 6.[175]

Emergency services

[edit]

Southampton's police service is provided by Hampshire Constabulary. The main base of the Southampton operation is a new, eight-storey purpose-built building which cost £30 million to construct. The building, located on Southern Road, opened in 2011 and is near to Southampton Central railway station.[176] Previously, the central Southampton operation was located within the west wing of the Civic Centre; however, the ageing facilities and the plans of constructing a new museum in the old police station and magistrates court necessitated the move. There are additional police stations at Portswood and Banister Park as well as a British Transport Police station at Southampton Central railway station. In the year ending June 2019, the crime rate in Southampton was higher than the average crime rate across similar areas.[177]

Southampton's fire cover is provided by Hampshire & Isle of Wight Fire and Rescue Service. There are three fire stations within the city boundaries at St Mary's, Hightown and Redbridge.

The ambulance service is provided by South Central Ambulance Service, who respond from stations in Nursling and Hightown, both on the outskirts of the city.[citation needed]

The national headquarters of the Maritime and Coastguard Agency is located in Commercial Road.

Education

[edit]

Southampton has two universities, namely the University of Southampton and Solent University.[178] Together, they have a student population of 40,000. Though students numbers had increased in the 80s, 90s, and up to 2011, they began to reduce due to changes in immigration rules and dropped further after 2016 due to Brexit. Of these, 2,880 are from EU, and the rest are from UK, Asia and Africa.[179][180]

The University of Southampton, which was founded in 1862 and received its Royal Charter as a university in 1952, has over 22,000 students.[181] The university is ranked in the top 100 research universities in the world in the Academic Ranking of World Universities 2010. In 2010, the THES - QS World University Rankings positioned the University of Southampton in the top 80 universities in the world. The university considers itself one of the top 5 research universities in the UK.[181][182][183] The university has a global reputation for research into engineering sciences,[184] oceanography, chemistry, cancer sciences, sound and vibration research,[185] computer science, electronics, and optoelectronics. It is also home to the National Oceanography Centre, Southampton (NOCS), the focus of Natural Environment Research Council-funded marine research.

Southampton Solent University has 17,000[186] students and its strengths are in the training, design, consultancy, research and other services undertaken for business and industry.[187] It is also host to the Warsash Maritime Academy, which provides training and certification for the international shipping and off-shore oil industries.

In addition to state school sixth forms at St Anne's and Bitterne Park School and an independent sixth form at King Edward's, there are two sixth-form colleges: Itchen College and Richard Taunton Sixth Form College, and a further education college, Southampton City College. A number of Southampton pupils travel outside the city, for example to Barton Peveril College.[citation needed]

There are 79 state-run schools in Southampton, comprising:

- 1 nursery school (The Hardmoor Early Years Centre in Bassett Green)

- 21 infant schools (ages 4 – 7)

- 16 junior schools (ages 7 – 11)

- 24 primary schools (ages 4 – 11)

- 8 secondary schools (ages 11 – 16)

- 2 secondary schools with sixth forms (ages 11–18)

- 3 secondary academies (Oasis Academy Mayfield, Oasis Academy Lord's Hill and Oasis Academy Sholing)

- 5 special schools[188]

There are also independent schools, including The Gregg School and King Edward VI School. Former independent schools included St Mary's Independent School and The Atherley School.

Transport

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2014) |

Road

[edit]Southampton is a major UK port which has good transport links with the rest of the country. The M27 motorway, linking places along the south coast of England, runs just to the north of the city. The M3 motorway links the city to London and also with the Midlands and North, via a link to the A34 (part of the European route E05) at Winchester. The M271 motorway is a spur of the M27, linking it with the Western Docks and city centre.[189]

Rail

[edit]

Southampton is served by the rail network, both by freight services to and from the docks and passenger services as part of the national rail system. The main station in the city is Southampton Central. Rail routes run:[190][191][192][193]

- East towards Portsmouth, Chichester, Worthing and Brighton;

- North to Winchester, the Midlands and London;

- West to Bournemouth, Poole, Dorchester and Weymouth;

- North-west towards Salisbury, Bristol and Cardiff.

The route to London was opened in 1840, by what was to become the London and South Western Railway Company. Both this and its successor, Southern Railway, played a significant role in the creation of the modern port following their purchase and development of the town's docks.

The town was the subject of an attempt by a separate company, the Didcot, Newbury and Southampton Railway, to open another rail route to the North in the 1880s and some building work, including a surviving embankment, was undertaken in the Hill Lane area. However an agreement was made to construct a junction with the existing LSWR main line south of Winchester.[194]

Air

[edit]Southampton Airport is a regional airport located in the town of Eastleigh, just north of the city. It offers flights to UK and near European destinations, and is connected to the city by a frequent rail service from Southampton Airport Parkway railway station[195] and by bus services.[196]

For longer flights, Gatwick Airport is linked by a regular rail service and Heathrow Airport is linked by National Express coach services.[197]

Ocean and cruise shipping

[edit]

Southampton's tradition of luxury cruising began in the 1840s, one of the pioneers being P&O, who advertised tours to Egypt.[198] The city was one of Europe's main ports for ocean passenger travel to North America and elsewhere, with British, French, and US liners regularly visiting.

Many of the world's largest cruise ships can regularly be seen in Southampton water, including record-breaking vessels from Royal Caribbean and Carnival Corporation & plc. The latter has headquarters in Southampton, with its brands including Princess Cruises, P&O Cruises, and Cunard Line.

The city has a particular historical connection to Cunard Line and their fleet of ships. This was particularly evident on 11 November 2008, when the Cunard liner Queen Elizabeth 2 departed the city for the final time amid a spectacular fireworks display, after a full day of celebrations.[199] Cunard ships are regularly christened in the city, for example Queen Victoria was named by The Duchess of Cornwall in December 2007, and the Queen named Queen Elizabeth in the city during October 2011. The Duchess of Cambridge performed the naming ceremony of Royal Princess on 13 June 2013.

At certain times of the year, the Queen Mary 2, Queen Elizabeth, and Queen Victoria may all visit Southampton at the same time, in an event commonly called 'Arrival of the Three Queens'. The Cunard Line maintains a regular transatlantic service to New York City for most of the year, with its ocean liner RMS Queen Mary 2.

The importance of Southampton to the cruise industry was indicated by P&O Cruises' 175th-anniversary celebrations, which included all seven of the company's liners visiting Southampton in a single day. Adonia, Arcadia, Aurora, Azura, Oceana, Oriana, and Ventura all left the city in a procession on 3 July 2012.[200]

The use of the port by cruise ships and bulk cargo ships has led to concerns over air quality.[201] In 2017 Southampton City Council estimated that the port contributed between seven and 23 per cent of air pollution in the city.[202] Cruise ships had to run their engines whilst docked because, unlike other cruise ship ports, Southampton did not provide shore power.[203] In 2019 an environmental pressure group ranked Southampton as the fifth highest in a list of 50 European ports whose air was polluted by sulphur oxide.[204] The cruise industry trade association Cruise Lines International Association claimed that the report was inaccurate and used highly questionable methodology.[205] Since September 2021, Port of Southampton has shore power installed at the Horizon Cruise Terminal at berth 102 and at the Mayflower Cruise Terminal at berth 106, both situated in the port's Western Docks.[206] Shore power will eventually be available at all five of the port's cruise terminals.[citation needed]

Ferry

[edit]While Southampton is no longer the base for any cross-channel ferries, it is the terminus for three internal ferry services, all of which operate from terminals at Town Quay. Two of these, a car ferry service and a fast catamaran passenger ferry service, provide links to East Cowes and Cowes, respectively, on the Isle of Wight and are operated by Red Funnel. The third ferry is the Hythe Ferry, providing a passenger service to Hythe on the other side of Southampton Water.

Southampton used to be home to a number of ferry services to the continent, with destinations such as San Sebastian, Lisbon, Tangier, and Casablanca. A ferry port was built during the 1960s.[207] However, a number of these relocated to Portsmouth and by 1996, there were no longer any cross-channel car ferries operating from Southampton with the exception of services to the Isle of Wight. The land used for Southampton Ferry Port was sold off and a retail and housing development was built on the site. The Princess Alexandra Dock was converted into a marina. Reception areas for new cars now fill the Eastern Docks where passengers, dry docks and trains used to be.

Bus

[edit]The main bus operator is Go South Coast – part of the Go Ahead group – which runs Bluestar as well as Unilink, QuayConnect and Salisbury Reds. First Solent runs services to Portsmouth via Fareham, while Xelabus also runs some routes.[208] There is also a door-to-door minibus service called Southampton Dial-a-Ride, for residents who cannot access public transport. This is funded by the council and operated by SCA Support Services.[209]

Tram

[edit]

There was a tram system from 1879 to 1949. More recent proposals to reintroduce them surfaced in 2016[210] and 2017,[211] and a monorail system was proposed in 1988.[212]

Throughout Southampton there are a number of what are locally called Lucy Boxes, so called because they were made by W. Lucy & Co. for power distribution.[213] They still remain along the routes even though the tram lines have been removed. Examples remain in other cities, including Wolverhampton.[214]

Cycling

[edit]Southampton City Council announced that it would adopt a new ten year 'Cycling Strategy' from 2017, which would include the construction of multiple cycling highways throughout the city and surrounding suburbs. As of March 2020, Southampton Cycle Network routes 1 (Western), 3 and 4 (Eastern), and 5 (Northern) are substantially complete, with work started on route 6 (Bevois Valley).[215]

Notable people

[edit]

People hailing from Southampton are called Sotonians.[216] The city has produced a large number of musicians throughout its history, ranging from hymn writer Isaac Watts, who was born in Southampton in 1674[217] and whose composition O God, Our Help in Ages Past is played by the bells of Southampton Civic Centre,[218] to more recent musical acts such as singer Jona Lewie, who was born in Southampton,[219] singer Craig David, who grew up on the Holyrood estate,[220] Coldplay drummer Will Champion,[221] and solo popstar Foxes.

Television personalities from Southampton include comedian Benny Hill[222] and naturalist Chris Packham;[223] in recent years the city has also produced a number of competitive reality television winners such as Matt Cardle (The X Factor, 2010)[224] and Shelina Permalloo (MasterChef, 2012), who operates a Mauritian restaurant named Lakaz Maman in Bedford Place.[citation needed] Radio personality Scott Mills was also born in Southampton.[225]

Novelist Jane Austen lived in Southampton for a number of years,[226] and the city has also been home to a number of artists, including Edward John Gregory,[227] Hubert von Herkomer,[228] and John Everett Millais.[229] The feminist and suffragist Emily Davies was born there in 1830.[230] Sir Leon Simon, President of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, was born in Southampton.[citation needed]

Sports people born in Southampton include rugby union player Mike Brown,[231] Australian tennis player Wally Masur,[232] England Football Player Wayne Bridge, and Republic of Ireland national football team player Lucy Quinn.

Being a port city, Southampton has been home to a number of seafarers, including Charles Fryatt, who rammed a German U-boat with his merchant ship during World War I;[233] John Jellicoe, who served as Admiral of the Fleet during the same war and later became Governor-General of New Zealand;[234] and the last survivor of the RMS Titanic, Millvina Dean.[235]

Richard Aslatt Pearce, the first deaf-mute Anglican clergyman, was born in Portswood, Southampton.[236]

Former Governor of Buenos Aires, and ruler of Argentina, Juan Manuel de Rosas went into exile in Swaythling in 1852. He was buried in Southampton Old Cemetery before his body was repatriated to La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires in 1989 by the then president Carlos Menem.

Ally Law, youtuber and parkour practitioner, was born in Southampton.[237]

Canadian pacifist Robert Edis Fairbairn (1879–1953) was born in Southampton.

Rishi Sunak, former UK prime minister and former Chancellor of the Exchequer, was born in Southampton in 1980.[238][239]

Film director Ken Russell was born in Southampton in 1927, and Laura Carmichael, actress known for Downton Abbey, was born and grew up in Southampton.

Freedom of the City

[edit]The following people and military units have received the Freedom of the City of Southampton.

Individuals

[edit]- Field Marshal Frederick Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts: 1901.

- Field Marshal Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener: 1902.

- David Lloyd George: 1923.

- Ted Bates: 2001.

- Matthew Le Tissier: 2002.

- Lawrence McMenemy: 2007.

- Dame Mary Fagan: 2 February 2013.[240]

- Francis Benali: 16 November 2016.[241][242]

- Albert Warne: 24 January 2022.[243]

Military units

[edit]- The Royal Hampshire Regiment: 25 April 1946.[244]

- 17 Port and Maritime Regiment, RLC: 26 January 2000.

- HMS Southampton, RN: 26 January 2000.[245]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "British urban pattern: population data" (PDF). ESPON project 1.4.3 Study on Urban Functions. European Union – European Spatial Planning Observation Network. March 2007. pp. 120–121. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Southampton BUA (E35001237)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 1 May 2019. Enter E35001237 if requested.

- ^ a b "Mid year population estimate 2016". Office for National Statistics. Southampton City Council. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ a b UK Census (2021). "2021 Census Area Profile – Southampton Local Authority (E06000045)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Global city GDP 2014". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ "Distance between London, UK and Southampton, UK (UK)". distancecalculator.globefeed.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "Distance between Southampton, UK and Portsmouth, UK (UK)". distancecalculator.globefeed.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Department for Transport (22 August 2018), UK Port Statistics: 2017 (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2019, retrieved 30 May 2019, puts Southampton third (by tonnage) after Grimsby and Immingham and the Port of London

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica. "Southampton". Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Roberts, Toby; Williams, Ian; Preston, John (2021). "The Southampton system: A new universal standard approach for port-city classification". Maritime Policy & Management. 48 (4): 530–542. doi:10.1080/03088839.2020.1802785. S2CID 225502755.

- ^ Southampton City Council. "Southampton's Titanic Story". Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Titanic | Crew from Southampton". www.dailyecho.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Solent Sky Museum. "Solent Sky | Southampton | Spitfire Legend". Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ BBC Online (8 June 2008). "Solent Ship Spotting". Archived from the original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ^ "Leading 20 retail centers in Great Britain". Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ^ Lewis, Gareth (18 December 2008). "Carnival UK HQ completed ahead of schedule". Daily Echo. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d Southampton Museum of Archeology. God's House Tower, Southampton.

- ^ Southampton Through the Ages: A Short History by Elsie M. Sandell (revised 1980)

- ^ British Archaeology Magazine (August 2002). "Great Sites: Hamwic". Archived from the original on 22 July 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

Hamwic, which is described as a commercial port (mercimonium). Hamwic (also known as Hamtun) must have possessed considerable administrative importance as by the middle of the 8th century it had given its name to the shire – Hamtunscire.

- ^ Southampton City Council. "Saxon Southampton". Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ^ a b c Southampton City Council. "Medieval Southampton". Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ^ Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone. p. 34. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ^ British Archaeology Magazine (August 2002). "Great Sites: Hamwic". Archived from the original on 22 July 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

The economic motor driving trade [was] larger-scale trade in relatively low value commodities such as wool, timber and quernstones

- ^ a b Alwyn A. Ruddock, The Greyfriars in Southampton, Papers & Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club & Archaeological Society, 16:2 (1946), pp. 137–47

- ^ a b c Rev. J. Silvester Davies, A History of Southampton Partly From the Ms. Of Dr Speed In The Southampton Archives, 1883, pp. 114–19

- ^ The National Archives, SC 8/17/833, Petitioners: People of Southampton. Addressees: King and council.

- ^ Internet Archive. "Monaco and Monte Carlo". Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d BBC Online. "Southampton Town Walls and Castle". Archived from the original on 23 March 2005. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ^ a b Southampton City Council. "God's House Tower: A History of the Museum". Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ^ Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone. p. 45. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ^ Southern Daily Echo (2 April 2008). "Red Lion Plot". Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ^ Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone. p. 48. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ^ "God's House Tower Museum of Archaeology, Southampton". Culture24. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ^ "Museum of archaeology (God's House Tower)". Southampton City Council. 27 September 2011. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone. p. 59. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ^ Percy G. Stone, A Vanished Castle, Papers & Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club & Archaeological Society, 12:3 (1934), pp. 241–70.

- ^ a b "The borough of Southampton: General historical account Pages 490–524 A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 3. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1908". British History Online. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ a b Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone. pp. 71–72. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ^ a b c Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone. pp. 78–79. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ^ Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone. pp. 95–97. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ^ Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone. p. 92. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ^ Southampton City Council. "Post-Medieval Southampton". Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ^ Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone. p. 120. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ^ Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone. p. 138. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ^ "Grand Theatre", Sotonopedia.

- ^ Dane, Kane (12 June 2019). "Southampton and Titanic". Titanic-Titanic.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ^ A History of Portswood, 2003, Book, P.Wilson

- ^ Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone. p. 169. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ^ "24 to be filmed in Southampton". 3 June 2014. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ "The War over Southampton – PortCities Southampton". Plimsoll.org. 6 November 1940. Archived from the original on 18 June 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Kieran Hyland (17 November 2016). "Your Guide to Southampton City Council". Wessex Scene. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ Emily Liddle (2 November 2018). "SKATE Southampton set-up ahead of return of Westquay Ice Rink". Southern Daily Echo. Newsquest. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ "Wimbledon comes to Southampton as Westquay opens its own 'Murray Mound'". Southern Daily Echo. Newsquest. 2 July 2018. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Oliver Wainwright (22 February 2018). "Studio 144: why has Southampton hidden its £30m culture palace behind a Nando's?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Greenwood & Co (1826). "Map of the County of Southampton". Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2007.