Stoke Poges

| Stoke Poges | |

|---|---|

| |

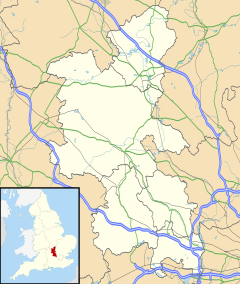

Location within Buckinghamshire | |

| Area | 10.09 km2 (3.90 sq mi) |

| Population | 4,752 (2011)[1] |

| • Density | 471/km2 (1,220/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | SU9884 |

| • London | 20.5 miles (33 km) E |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | SLOUGH |

| Postcode district | SL2 |

| Dialling code | 01753 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Buckinghamshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | www |

Stoke Poges (/ˈstoʊkˈpoʊdʒɪz/) is a village and civil parish in south-east Buckinghamshire, England. It is centred 3 miles (4.8 km) north-north-east of Slough, its post town, and 2 miles (3.2 km) southeast of Farnham Common.

Etymology

[edit]In the name Stoke Poges, stoke means "stockaded (place)" that is staked with more than just boundary-marking stakes. In the Domesday Book of 1086, the village was recorded as Stoche. William Fitz-Ansculf, who held the manor in 1086 (in the grounds of which the Norman parish church was built), later became known as William Stoches or William of Stoke. Amicia of Stoke, heiress to the manor, married Robert Pogeys, Knight of the Shire 200 years later, and the village eventually became known as Stoke Poges. Robert Poges was the son of Savoyard Imbert Pugeys, valet to King Henry III and later steward of the royal household. Poges and Pocheys being an English attempt at Pugeys which ironically meant "worthless thing".[2] The spelling appearing as "Stoke Pocheys", if applicable to this village, may suggest the pronunciation of the second part had a slightly more open "o" sound than the word "Stoke".[3]

Stoke Poges Manor House

[edit]A manor house at Stoke Poges was built before the Norman Conquest and was mentioned in the 1086 Domesday Book. In 1555 the owner, Francis Hastings, 2nd Earl of Huntingdon, pulled down much of the existing fortified house. He replaced it with a large Tudor brick-built house, with numerous chimneys and gables.[4] In 1599 it was acquired by Sir Edward Coke, who is said to have entertained Queen Elizabeth I there in 1601.[5]

A few decades later, the married lady of the manor, Frances Coke, Viscountess Purbeck, the daughter of Sir Edward Coke, had a love affair with Robert Howard, a member of parliament. The affair's discovery was received as a scandal upon the three people involved, and in 1635 Lady Frances was imprisoned for adultery. She later escaped from prison to France, and eventually returned and lived at Stoke Poges Manor for a time. She died at Oxford in 1645 at the court of King Charles I.[6]

n August 1647 Charles I spent a night or two there, as a prisoner, on his removal from Moor Park, Rickmansworth on the way to his execution.[7][8]

Later the manor came into the possession of Thomas Penn, a son of William Penn who founded Pennsylvania and was its first proprietor. Thomas Penn held three-fourths of the proprietorship. The manor property remained in his family for at least two generations, as his son John Penn "of Stoke" also lived there. Thomas Gray's 1750 poem "A Long Story" describes the house and its occupants.[9] Sir Edwin Henry Landseer was a frequent visitor to the house and rented it as a studio for some time. His most famous painting, The Monarch of the Glen (1851), is said to have been created at Stoke Poges, with the deer in the park used as models.[10]

In 2012 the property was sold, by South Bucks District Council, for a sum of £300,000. It was bought by a property developer and was subsequently advertised for sale at £13.5 million.[11]

Education

[edit]Stoke Poges has a primary school called The Stoke Poges School.[12] It was rated 'Good' by Ofsted in 2022.[13] On 6 May 1985 four pupils drowned at Land's End during a school trip. Their bereaved parents were angered by Buckinghamshire County Council's offer of £3500 compensation per child.[14]

A Sikh faith secondary school called Pioneer Secondary Academy opened in 2022.[15][16][17] On the site had been Khalsa Secondary Academy which had been rated 'Inadequate ' by Ofsted in 2019 and subsequently closed.[18][19][20]

Larchmoor School in Gerrards Cross Road was a major school in England for deaf children which was opened in 1967 by Elizabeth II and ran by the Royal National Institute for Deaf People. It closed in the late 20th century.[21][22][23]

Halidon House School was founded 1865, based in Slough and then in 1948 moved to Framewood Manor, Framewood Road. It was a girls school which closed in 1983.[24][25][26]

St. James Roman Catholic School moved from Richmond in 1830 to Baylis House. The school closed in 1907. Rafael Merry del Val, Cardinal Secretary of State under Pope Pius X was educated at the school.[27][28]

Stoke House School in Stoke Green was a preparatory school from 1841 to 1913.[29][30] In 1913 Ted Parry, the headmaster relocated the school to Seaford and later it was renamed Stoke Brunswick School.[31]

Long Dene School, moved from Jordans, Buckinghamshire to the Manor House in 1940. In 1945 the school relocated to Chiddingstone Castle, Kent.[32][33]

Teikyo School United Kingdom is near Stoke Poges.[34]

St Giles' Church

[edit]Thomas Gray's "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard" is believed to have been written in the churchyard of Saint Giles. The church is a Grade I listed building.[35][36][37] Other churches have claimed the honour, including St Laurence's Church, Upton-cum-Chalvey and St Mary's in Everdon, Northamptonshire.

Gray is buried in a tomb with his mother and aunt in the churchyard.[38] John Penn commissioned James Wyatt to design a monument which is a Grade II* listed building. It bears lines from the Elegy.[39] The monument stands adjacent to St Giles' church and owned by the National Trust.[40]

A lychgate which is now located in the middle of the churchyard was designed by John Oldrid Scott and completed in 1887.[41] In 2022 it became a national heritage asset being Listed Grade II.[42]

A gothic style rectory having a battlemented parapet was built by James Wyatt, 1802–1804 for John Penn of Stoke Park. It is now a private residence called Elegy House.[43]

Sport

[edit]There are two public recreation grounds: Bells Hill and Plough Lane.[44] In the late 20th century, large private sports facilities operated for the main benefit of Glaxo Laboratories staff at Sefton Park[45][46] and for Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) Paints Division[47] at Duffield House, Stoke Green.[48]

Badminton: Stoke Poges Badminton Club has for many decades run in the Village Centre.[49][50]

Bowls: Stoke Poges Bowls Club was founded in 1978 and closed in 2020. The bowling green was situated in the grounds of the Polish Association in Church Lane. The bowling green had opened in 1949 by St. Helens Cable and Wire Company.[51]

Cricket: Stoke Green Cricket Club in Stoke Green has been playing there since 1879 with support of the then landowner, Howard-Vyse of Stoke Place.[52] Stoke Poges Golf Club at Stoke Park used to run a cricket club in the early 20th century, playing home matches in Farnham Royal.[53]

Darts: In 2023 darts teams from the Village Centre and the Rose and Crown public house in Stoke Poges, compete in the Chalfont and District Darts League.[54][55]

Football: Stoke Poges Football Club plays on the Bells Hill recreation ground.[56][57]

Golf: Stoke Park golf course was designed by Harry Colt for Nicholas Lane Jackson who founded it in 1908 as part of England's first golf and country club. It was known as Stoke Poges Golf Club.[58][59] The South Buckinghamshire Golf Academy consisted of a 9 holes golf course and a golf driving range. It was opened in 1994 and owned by Buckinghamshire County Council. It closed down after the granting of a planning application in 2018 to turn it into a public Country Park.[58][60] The South Buckinghamshire Golf Course, formerly known as Farnham Park Golf Course, is an 18-hole pay and play course, set in 130 acres of mature wooded parkland owned by Buckinghamshire Council.[61][58] In 2023 there were two golf clubs using the course: South Buckinghamshire Golf Club[62] and Farnham Park Golf Club. The latter was established at the course in 1977.[63] Wexham Park Golf Centre in Wexham Street, straddles Stoke Poges and Wexham Parishes. It has a variety of golf facilities with a nine hole course being located in Stoke Poges Parish.[64][58]

Padel: In 2023 Buckinghamshire Council submitted plans to build two padel tennis courts at the South Buckinghamshire Golf Course.[65]

Table Tennis: Stoke Poges Table Tennis Club was founded in 1950. Play used to take place in the pavilion at Sefton Park. In the 21st century it plays at St Andrew's Church Centre in Rogers Lane.[66]

Tennis: Stoke Poges Lawn Tennis Club operates on Bells Hill recreation ground and commenced there in 1949.[67][68]

In media

[edit]- In 1931 Aldous Huxley wrote his book Brave New World which mentions Stoke Poges in it. He frequently visited Stoke Poges golf course.[69]

- In 1957, British Pathé filmed ‘The Vital Vaccine’ at Sefton Park where Glaxo Laboratories created and manufactured the 'Polyvirin', Britain's Polio vaccine. The Chairman of Glaxo’, Sir Harry Jephcott is filmed. It is announced at the start of the film, that it is the former home of the music hall star, Vesta Tilley[70]

- In 1963 the film I Could Go On Singing with Judy Garland's character visits St Giles' parish church with her son.[71]

- In 1964 the golf course at Stoke Park was the setting of a golf match in the James Bond film Goldfinger, played between the principal characters.[72] The map on the dial in Bond's car that tracks Goldfinger's shows Stoke Poges.

- In 1969, Pinewood film studios hired a chemistry laboratory at Fulmer Research Institute for use as a film set for the film "The Chairman" (also known as "The Most Dangerous Man in the World"), starring Gregory Peck.[73]

- In 1981 the James Bond film For Your Eyes Only filmed its opening sequence, when Bond visits his wife's grave, in the graveyard at St Giles' Church.[74]

- In 1990 'Inspector Lynley' crime novel Well-Schooled in Murder by Elizabeth George, and its television adaptation, are set in Stoke Poges.

- In 1996, Nick Hancock's Football Nightmares Nick Hancock is trying to hitchhike to the Victoria Ground in Stoke-on-Trent, but keeps getting dropped off in, or just outside, Stoke Poges.[75]

- In 1997 James Bond film Tomorrow Never Dies, Stoke Park hotel doubles as the interior of the Hamburg hotel, where Bond (Pierce Brosnan) drinks his vodka, renews his past relationship with Carver's wife Paris (Teri Hatcher) and struggles with Dr. Kaufman (Götz Otto).[76]

- In 1998, the novel Sharpe's Triumph by Bernard Cornwell was published. In the novel, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington's dragoon orderly Daniel Fletcher mentions that he is from Stoke Poges: Sharpe replies- "Never heard of it.”[77]

- In 2004 Stoke Park is also featured in the films Layer Cake. also filmed there was Wimbledon (2004), Bride and Prejudice, (2004) and Bridget Jones's Diary.(2001)[78]

- In 2007, Part of the 2007 series Jekyll was filmed on the boardwalk and surrounding area.

- In 2010, the BBC drama series Vexed (Series 1, Ep.2, TX 22 Aug 2010 – with Toby Stephens and Lucy Punch) was largely filmed in the grounds and inside Stoke Court – which had earlier been Bayer Group UK's conference centre.

- In 2017 the British media caused a furore after the National Galleries of Scotland had bought The Monarch of the Glen painting by Sir Edwin Landseer for £4 million and the view by some that it may have been painted at Stoke Park.[79][80]

- In 2021, the lease of Stoke Park was bought by Reliance Industries (RIL) for £57 million from the International Group. Later in the year Stoke Park closed for refurbishment.[81][82][83][84]

- In 2021, Stoke Poges Memorial Gardens featured in the BBC programme Great British Railway Journeys presented by Michael Portillio[85][86][87]

- In 2021, Prime Minister, Boris Johnson in his keynote speech at the Conservative Party Conference referred to Thomas Gray and Stoke Poges, about a levelling up vision in terms of an imbalanced society.[88][89]

Notable natives and residents

[edit]- Augustus Henry Eden Allhusen (1867–1925), English politician, resident at Stoke Court, Rogers Lane (1867–1925)[90]

- Christian Allhusen (1806–1890), Danish-English chemical manufacturer, resident at Stoke Court, Rogers Lane.[91]

- John Charles Bell (1844–1924), 1st Baronet, Lord Mayor of London and businessman, resident at Framewood Manor, Framewood Road (1905–1924).[92][93]

- John Beresford (1866–1944), 5th Baron Decies, Army officer, civil servant and baron, resident at Sefton Park (1905–1917)[94]

- Robert Brooke-Popham (1878–1953), Air Chief Marshal in the Royal Air Force and Governor of Kenya, resident at The Woodlands, Hollybush Hill.[95]

- Wilberforce Bryant (1837–1906), English businessman, owner of Bryant & May match manufacturer and Quaker, resident at Stoke Park (1887-1906).[96] : 70–77 [97]

- Edward Coke (1552–1634), Lord Chief Justice of England and politician, resident at the Manor House (1598-1634).[96]: 25–28

- Abraham Darby IV (1804–1878), English ironmaster, resident at Stoke Court, Rogers Lane (1851–1872).[98]

- Walter de Frece (1870-1935), British theatre impresario and politician, resident at Sefton Park with his wife, Vesta Tilley in the 1920s.[99]

- Wallace Charles Devereux (1893–1952), English businessman and engineer, founder of Fulmer Research Institute in Stoke Poges and resident at The Meads, Park Road.[100]

- John Thomas Duckworth (1748–1817), Admiral in the Royal Navy and baronet spent his childhood at the Vicarage, Park Road, where his father lived, being the Vicar of Stoke Poges (1754–1748).[101][102]

- Ruth Durlacher (1876-1946), Irish tennis player and golfer, resident at the White House and Pinegrove, Stoke Green, in early 20th century.[103][104]

- Walter Evelyn Gilliat (1869-1963), England footballer and Minister in the Church of England, resident at Duffield House where his father, Algernon, lived, Stoke Green[105][106]

- Henry Godolphin (1648-1733) Dr., Provost of Eton College and Dean of St Paul's cathedral, resident at Baylis House in 18th century.[107][108]

- Alfred Frank Hardiman (1891-1949), sculptor, resident at Farthing Green house.[109][110]

- Francis Hastings (1514–1561), 2nd Earl of Huntingdon, politician, 1555 completed building of the Manor house.[111]

- Elizabeth Hatton (1578-1646), 2nd wife of Edward Coke, resident at the Manor House.[112]

- George Howard (1718–1796), Field Marshal in British Army and politician, resident at Stoke Place, Stoke Green (c.1764–1796).[113][114]

- Richard Howard-Vyse (1883–1962), Major General and Honorary Colonel of the Royal Horse Guards, resident at Stoke Place, Stoke Green (1883–1962)[115]

- Richard William Howard Howard Vyse (1784–1853), Major General and Egyptologist, born in Stoke Poges and resident at Stoke Place, Stoke Greens.[116]

- Nick 'Pa' Lane Jackson (1849–1937), founder of Stoke Park, sports administrator and author, resident Stoke Park (1908–1928).[117][96]: 100–186

- Alfred Webster 'Morgan' Kingston (1875-1936), tenor, opera singer, resident in Templewood Lane.[118][119]

- Henry Labouchere (1798–1869), 1st Baron Taunton, British Whig politician, resident at Stoke Park (1848–1863).[96]: 62–66

- Jacques Laffite (born 1943) the French Formula One racing driver who won six Grands Prix for Ligier during the late 1970s and early 1980s, lived in Stoke Poges during some of his racing career.[citation needed]

- Henry Martin (Marten) (c.1562–1641), King's Advocate for James I and Judge of Admiralty Court is reported to have been born at Stoke Poges.[120]

- Noel Mobbs (1878–1959), businessman, founder of Slough Estates, resident at Stoke Park (1928–1959).[121][96]: 188–213

- William Moleyns (1378–1425), politician, administrator, knight to Henry V, resident at the Manor House.[122][123][124]

- William Molyneux (1772–1838), sportsman and gambler, resident at Stoke Farm, now known as Sefton Park (1795–1838).[125]

- Bernard Oppenheimer (1866–1921), diamond merchant and philanthropist, resident at Sefton Park, Bells Hill (1917-1921).[126]

- Sydney Godolphin Osborne (1808–1889), Lord, cleric, writer, philanthropist, vicar of Stoke Poges (1832–1841).[127]

- Edward Hagarty Parry (1855–1931), International footballer & school headmaster, resident at Stoke House School, Stoke Green, (1855-1913).[128]

- Granville Penn (1761–1844), author, scriptural geologist and civil servant, resident at Stoke Park (1761-1844).[129][96]: 61

- John Penn (1760–1834), Chief Proprietor of Province of Pennsylvania, politician and writer, resident at Stoke Park (1760–1834).[130]

- Thomas Penn (1702–1775), son of William Penn and proprietor of Province of Pennsylvania, with three-fourths holding, resident at the Manor House, Stoke Park (1760–1775).[131]

- Borradaile Savory (1855–1906), English clergyman and baronet, resident at The Woodlands, Hollybush Hill (1855–1906).[132]

- William Scovell Savory (1826–1895), British Surgeon and baronet, resident at The Woodlands, Hollybush Hill (1884–1895).[133]

- Philip Stanhope (1694-1773), 4th Earl of Chesterfield, British statesman and diplomat, resident at Baylis house in 18th century.[134][135]

- Vesta Tilley (Matilda Alice Powles) (1864–1952), music hall performer, resident at Sefton Park in the 1920s with her husband Walter de Frece.[136]

- Alexander Wedderburn (1733-1805), 1st Earl of Rosslyn, Lord High Chancellor, resident at Baylis House, late 18th century and early 19th century.[137]

Notable organisations

[edit]- Comer Group, is a real estate company which c.2010 became the owner of Stoke Court for part of its residential portfolio.[138][139]

- Hitachi Data Systems, is a subsidiary of Hitachi. It provides technology and services relating to digital data. UK Headquarters at Sefton Park, Bells Hill, Stoke Poges.[140]

- International Group operates a group of companies in the leisure, sales, marketing, management, healthcare services and property development and ownership. Registered at Stoke Park until 2021, when the lease was sold to Reliance Industries[141][142]

- Reliance Industries Limited (RIL), an Indian multinational conglomerate, on the Global 500 list, bought the lease of Stoke Park in 2021[143]

- Servier Laboratories Ltd, is part of a French centric international pharmaceutical group. UK Headquarters at Sefton Park, Bells Hill, Stoke Poges.[144]

- Urenco Ltd, a nuclear fuel company, operating internationally running uranium enrichment plants. Headquarters at Sefton Park, Bells Hill, Stoke Poges.[145]

- Fulmer Research Institute, a pioneer contract research and development organisation. Its Headquarters was in Hollybush Hill, Stoke Poges from 1946 to 1990.[146]

- Glaxo Laboratories Ltd, now part of GSK, a fermentation and vaccine research laboratory at Sefton Park, Bells Hill, Stoke Poges from 1948 to 1982: (NB: see 'In Media' section above - 1957, British Pathé filmed ‘The Vital Vaccine’ at Sefton Park) [147]

- Miles Laboratories, a USA pharmaceutical and life sciences company. UK headquarters in Stoke Court, Rogers Lane, Stoke Poges from 1959 to 1978 when Bayer acquired it.[148][149]

Demography

[edit]| Stoke Poges compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK Census | Stoke Poges ward |

South Bucks borough |

England |

| Population | 4,839 | 61,945 | 49,138,831 |

| Foreign born | 11.9% | 12.2% | 9.2% |

| White | 93.3% | 93.4% | 90.9% |

| Asian | 4.8% | 4.5% | 4.6% |

| Black | 0.3% | 0.4% | 2.3% |

| Christian | 76.5% | 75.6% | 71.7% |

| Muslim | 1.1% | 1.1% | 3.1% |

| Hindu | 0.7% | 1.2% | 1.1% |

| No religion | 10.6% | 12.5% | 14.6% |

| Unemployed | 1.8% | 1.9% | 3.3% |

| Retired | 16.8% | 14.8% | 13.5% |

At the 2001 UK census, the Stoke Poges electoral ward had a population of 4,839. The ethnicity was 93.3% white, 1.3% mixed race, 4.8% Asian, 0.3% black and 0.3% other. The place of birth of residents was 88.1% United Kingdom, 1.6% Republic of Ireland, 2.5% other Western European countries, and 7.8% elsewhere. Religion was recorded as 76.5% Christian, 0.2% Buddhist, 0.7% Hindu, 2.7% Sikh, 0.5% Jewish, and 1.1% Muslim. 10.6% were recorded as having no religion, 0.2% had an alternative religion and 7.6% did not state their religion.[150]

The economic activity of residents aged 16–74 was 40.8% in full-time employment, 11.6% in part-time employment, 12.6% self-employed, 1.8% unemployed, 1.5% students with jobs, 3.1% students without jobs, 16.8% retired, 6.7% looking after home or family, 2.5% permanently sick or disabled and 2.5% economically inactive for other reasons. The industry of employment of residents was 15.4% retail, 13.4% manufacturing, 6.9% construction, 21.1% real estate, 9.2% health and social work, 7.3% education, 8.8% transport and communications, 3.5% public administration, 3.4% hotels and restaurants, 2.8% finance, 0.8% agriculture and 7.4% other. Compared with national figures, the ward had a relatively high proportion of workers in real estate, transport and communications. According to Office for National Statistics estimates, during the period of April 2001 to March 2002 the average gross weekly income of households was £870, compared with an average of £660 in South East England. Of the ward's residents aged 16–74, 28.4% had a higher education qualification or the equivalent, compared with 19.9% nationwide.[150]

In 2011, The Daily Telegraph deemed Stoke Poges as Britain's eighth richest village and the third richest village in Buckinghamshire.[151]

| Output area | Homes owned outright | Owned with a loan | Socially rented | Privately rented | Other | km2 roads | km2 water | km2 domestic gardens | km2 domestic buildings | km2 non-domestic buildings | Usual residents | km2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Civil parish | 727 | 717 | 183 | 159 | 28 | 0.397 | 0.076 | 1.422 | 0.176 | 0.057 | 4752 | 10.09 |

Geography

[edit]Hamlets within Stoke Poges parish include:

- Hollybush Hill

- Stoke Green

- West End

- Wexham Street

References

[edit]- ^ a b Key Statistics: Dwellings; Quick Statistics: Population Density; Physical Environment: Land Use Survey 2005

- ^ David Carpenter. 2020. Henry III : The Rise to Power and Personal Rule 1207 – 1258. New Haven: Yale University Press. 360.

- ^ Plea Rolls of the Court of Common Pleas; National Archives; CP40/647; http://aalt.law.uh.edu/AALT1/H6/CP40no647/aCP40no647fronts/IMG_0029.htm; second entry, with "London" in the margin, & with defendants Thomas Clerk, William Adam, John Lambard & John Spykernell of Stoke Pocheys.

- ^ "MANOR HOUSE, Stoke Poges - 1165194 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Norsworthy, Laura (1935). The Lady of Bleeding Heart Lane. London: John Murray. p. 16.

- ^ Norsworthy, Laura (1935). The Lady of Bleeding Heart Lane. London: John Murray. p. 292.

- ^ Anon. "Stoke Poges Parish Council". Stoke Poges Parish Council. Stoke Poges Parish Council. Retrieved 12 December 2024.

- ^ https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/bucks/vol3/pp302-313

- ^ "A Long Story". Thomas Gray Archive. December 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ "Hotel claims Monarch of the Glen stag was English". BBC News. 26 October 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ https://www.bucksfreepress.co.uk/news/9701227.why-was-historic-stoke-poges-manor-house-sold-for-so-little/

- ^ "The Stoke Poges School - GOV.UK". www.get-information-schools.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Ofsted – Short inspection on The Stoke Poges School". Gov.uk. 19 December 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Leeming, Jan (presenter) (8 September 1985). "10 O'Clock News". BBC News. Event occurs at 6:00. BBC One.

- ^ "Pioneer Secondary Academy". Pioneer Secondary Academy. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Singh, Tarvinder. "Home". Sikh Academies Trust. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Pioneer Secondary Academy - GOV.UK". www.get-information-schools.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Inspection Report on Khalsa Secondary Academy". Gov.uk. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "High Court reveals Khalsa Academies Trust's safeguarding failures". schoolsweek.co.uk. 8 October 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Termination notice to Khalsa Secondary Academy". GOV.UK. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "LARCHMOOR SCHOOL, Stoke Poges | UCL UCL Ear Institute & Action on Hearing Loss Libraries". University College London. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ BOOTH, L.G. (1997). "The design and construction of timber hyperbolic paraboloid shell roofs in Britain: 1957–1975". Construction History. 13: 78. ISSN 0267-7768. JSTOR 41613779.

- ^ "Larchmoor School for the Deaf". The Royal National Institute for the Deaf. 22: 99–103. April 1967.

- ^ Fraser, Maxwell (1980). "9". The History of Slough. Slough: Slough Corporation. p. 94. OCLC 58814912.

- ^ "FRAME WOOD MANOR (HALIDON HOUSE SCHOOL), Stoke Poges - 1124349 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Archives, The National. "The Discovery Service". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Harris, L.H. (7 March 2023). "Baylis House".

- ^ "Buckinghamshire Gardens Trust - Baylis House" (PDF). 7 March 2023.

- ^ "STOKE HOUSE, Stoke Poges – 1317440 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Items relating to Stoke House and other schools records". Buckcc.gov.uk. 1879–1940. D-X 801/18. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "Stoke Brunswick School". The Keep, East Sussex. 1886–1959. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "The Long Dene Community". The Long Dene Community. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Smithson, Sue (1999). Community adventure : the story of Long Dene School. London: New European Publications. ISBN 1-872410-13-8. OCLC 44915980.

- ^ "Village Voice". Beaconsfield Advertiser. Uxbridge. 30 September 1998. p. 18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hoyle, Joshua Fielding (1920). The Country Churchyard – Stoke Poges Church. Oxford, UK: Church Army Press.

- ^ "Stoke Poges Church". stokepogeschurch.org. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Church of St Giles, Stoke Poges (Grade I) (1164966)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "Tomb of Thomas Gray, his mother Dorothy Gray and his aunt Mary Antrobus in churchyard of St Giles Church, Stoke Poges (Grade II) (1124345)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "Gray's Monument, Stoke Poges (Grade II*) (1124346)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ "Gray's Monument and Gray's Field Stoke Poges, Buckinghamshire". National Trust. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Blake, Rev. Vernon (22 November 1887). "Stoke Poges Church". The Times newspaper. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Lych gate and attached stone and flint wall, Church of St Giles, Stoke Poges (Grade II) (1475583)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "St Giles' Vicarage (Grade II) (1332767)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ "Recreation Grounds | Stoke Poges Parish Council". Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Hitachi Data Systems: Sefton Park - A history - Promotional Item - Computing History". www.computinghistory.org.uk. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Sefton Park | Stoke Poges Parish Council". Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ Johnson, Alan Woodworth (1977). "John Donald Rose, 2 January 1911 - 14 October 1976". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 23: 449–463. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1977.0017. S2CID 70495969.

- ^ "Duffiled House Conference Brochure by Joshua Keys - Issuu". issuu.com. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Stoke Poges Badminton Club | Stoke Poges Parish Council". Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Badminton Club at Stoke Poges Village Centre". www.stoke-poges-centre.org.uk. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Stoke Poges Bowls Club | Stoke Poges Parish Council". Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Stoke Green Cricket Club".

- ^ "Cricket 1911". archive.acscricket.com. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "The Chalfont & District Darts League - Home". cddl.leaguerepublic.com. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Stoke Poges Village Centre Social Club". www.stoke-poges-centre.org.uk. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Stoke Green Rovers FC | Stoke Poges Parish Council". Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Stoke Poges Saints First | East Berkshire Football League". fulltime.thefa.com. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Golf | Stoke Poges Parish Council". Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "History of Stoke Park -". Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Buckinghamshire Council - Planning Application".

- ^ "Home". The South Buckinghamshire. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Noticeboard". sbgc-live. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Home - FARNHAM PARK GOLF CLUB". www.farnhampark.co.uk. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Wexham Park Golf Centre". www.wexhamparkgolfcentre.co.uk. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Buckinghamshire Council - Planning Application".

- ^ "Stoke Poges Table Tennis Club | Stoke Poges Parish Council". Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Stoke Poges Lawn Tennis Club – Play tennis in the heart of the village". Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Stoke Poges Tennis Club | Stoke Poges Parish Council". Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (1998). Brave New World (First Perennial Classics ed.). New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-092987-1.

- ^ "THE VITAL VACCINE". British Pathé. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ Neame, Ronald (14 August 1963), I Could Go on Singing (Drama, Music), Barbican Films, retrieved 6 March 2023

- ^ "Goldfinger film locations (1964)".

- ^ J. Lee Thompson (Director), Gregory Peck (Actor) (1969). "The Chairman" (also known as "The Most Dangerous Man in the World") (Film). Pinewood Studios, Buckinghamshire, England: Twentieth Century Fox.

- ^ "For Your Eyes Only film locations".

- ^ Nick Hancock's Football Nightmares (1996), 21 October 1996, retrieved 6 March 2023

- ^ "Over 25 Years of 007 Filming Locations in England". Filming in England. 9 September 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ "Sharpe's Triumph | Bernard Cornwell". www.bernardcornwell.net. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ "History of Stoke Park -". Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ "Hotel claims Monarch of the Glen stag was English". BBC News. 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Sir Edwin Landseer". nationalgalleries.org. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Luxury golf club and hotel to shut for two years after Indian billionaire buys it for £57 million". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Luxury Hotel, Spa, Golf & Country Club in Buckinghamshire | Stoke Park". www.stokepark.com. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Barman, Arijit. "Reliance all set to buy iconic British Country Club Stoke Park for 60 mn pounds". The Economic Times. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Cradock, Matt (30 May 2021). "Stoke Park Country Club To Shut For Two Years After Takeover". Golf Monthly Magazine. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "BBC Two – Great British Railway Journeys, Series 12, West Ruislip to Windsor". BBC. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "BBC's Great British Railway Journey's next stop is Stoke Poges Memorial Gardens". Buckinghamshire Council. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Bucks memorial gardens set to feature on popular BBC TV show". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Affluent Stoke Poges welcomes plan to 'take pressure off' by levelling up". The Guardian. 6 October 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Levelling up is Johnson's answer to chill penury". churchtimes.co.uk. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Debrett's House of Commons and the Judicial Bench 1901. London: Dean & Son. 1901. p. 2. Retrieved 20 January 2021

- ^ Chemist and Druggist, Volume 36. Benn Brothers. 1890. p. 61. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ South Bucks District Council (19 July 2011). "Framewood Road Character Appraisal". southbucks.gov.uk. p. 22. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Slough Windsor Eton Observer (26 January 2021). "Death of Slough Magistrate". sloughhistoryonline.org.uk.

- ^ : 67 Rigby, Lionel (2000). Stoke Poges – A Buckinghamshire village through 1000 years. Phillimore. ISBN 9781860771316.

- ^ Kelly's directory of Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire. 1935. Kelly's Directories Ltd. 1935. pp. Stoke Poges. OCLC 1114860090.

- ^ a b c d e f Pugh, Peter (2008). Stoke Park the first 1000 years. Icon Books. ISBN 978-184-046-946-2.

- ^ Corley, T. A. B. (2004). "Bryant, Wilberforce (1837–1906), match manufacturer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/46787. Retrieved 26 January 2021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "No. 21409". The London Gazette. 8 February 1853. p. 329.

- ^ "Recollections of Vesta Tilley | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ "Fulmer Research Institute, timeline". 23 January 2021.

- ^ "DUCKWORTH, Sir John Thomas (1748–1817). | History of Parliament Online". www.historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Stoke Poges Heritage Walk – Map". Buckinghamshire.gov.uk. Item B. Buckinghamshire Council. 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Page 2941 | Issue 34156, 3 May 1935 | London Gazette | The Gazette". www.thegazette.co.uk. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ 1935 Kelly's Directory of Berkshire and Oxfordshire. Kelly's Directories Ltd. 1935. pp. Stoke Poges.

- ^ "FamilySearch.org". ancestors.familysearch.org. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "England Players - Walter Gilliat". www.englandfootballonline.com. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Godolphin, Henry (1648–1733), college head and dean of St Paul's". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10878. Retrieved 6 March 2023. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Buckinghamshire Sites – Parks – Buckinghamshire Gardens Trust". Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ "Alfred Frank Hardiman". London Remembers. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Alfred Frank Hardiman RA, RS, FRBS - Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851-1951". sculpture.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "MANOR HOUSE, Stoke Poges – 1165194 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Aughterson, Kate (2004). "Hatton, Elizabeth, Lady Hatton [née Lady Elizabeth Cecil; other married name Elizabeth Coke, Lady Coke] (1578–1646), courtier". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68059. Retrieved 14 February 2023. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Sir George Howard". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13900. Retrieved 13 July 2014. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Parishes: Stoke Poges, A History of the County of Buckingham: Volume 3 (1925)". pp. 302–313. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ Anglesey, The Marquess of (1994). A History of the British Cavalry: Volume 5: 1914–1919 Egypt, Palestine and Syria. Pen & Sword Books Ltd. ISBN 9780850523959.

- ^ 1851 England Census HO107/1718; Folio: 579; Page: 17

- ^ Jackson, Nick Lane (1932). Sporting Days and Sporting Ways. London, UK: Hurst and Blacket. OCLC 1073277963.

- ^ "Morgan Kingston". www.historicaltenors.net. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Morgan Kingston". Our Mansfield & Area. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Brief Lives John Aubrey Clarendon Press, 1898 – Great Britain

- ^ "Sir Noel Mobbs | English Bridge Union". www.ebu.co.uk. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Neale, John Preston (1824). Views of the most interesting Collegiate and Parochial Churches in Great Britain – St Giles' Church, Stoke Poges – The Rev Arthur Bold. Volume 1. London: John le Keux. OCLC 939440882.

- ^ Bryant Bevan, The Rev. D.H. (1948). "The Country Churchyard Stoke Poges Church". R.G. Baker & Co. Ltd, Farnham Common, Buckinghamshire: 17.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Woodger, L. S. (1993), "Moleyns, Sir William (1378–1425), of Stoke Poges, Bucks", in J.S. Roskell; L. Clark; C. Rawcliffe (eds.), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1386–1421, retrieved 31 January 2021

- ^ Rigby, Lionel (2000). "20". Stoke Poges – A Buckinghamshire village through 1000 years. Phillimore. p. 74. ISBN 9781860771316.

- ^ "No. 32776". The London Gazette. 12 December 1920. p. 8839.

- ^ "Osborne, Lord Sydney Godolphin (1808–1889), philanthropist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20883. Retrieved 1 February 2021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Betts, Graham (2006). England: Player by player. Green Umbrella Publishing. p. 187. ISBN 1-905009-63-1.

- ^ Fell-Smith, Charlotte (2004). "Penn, Granville (1761–1844)". In Smail, Rev. Richard (ed.). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21847. Retrieved 25 January 2021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Penn, John (PN776J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Wainwright, Nicholas B. (1963). "The Penn Collection". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 87 (4): 393–419. ISSN 0031-4587. JSTOR 20089651.

- ^ "Savory, Borradaile (SVRY875B)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Framewood Road Conservation Area Character Appraisal report (19 July 2011).South Bucks District Council

- ^ Cannon, John (2004). "Stanhope, Philip Dormer, fourth earl of Chesterfield (1694–1773), politician and diplomatist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26255. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 6 March 2023. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Fraser, Maxwell. "Salt Hill". www.sloughhistoryonline.org.uk. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ De Frece, Lady (1934). Recollections of Vesta Tilley. Hutchinson. OCLC 754988460.

- ^ Murdoch, Alexander (2004). "Wedderburn, Alexander, first earl of Rosslyn (1733–1805), lord chancellor". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28954. Retrieved 6 March 2023. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Residential Portfolio UK". thecomergroup.com. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Kingsley, Nick (9 February 2014). "Landed families of Britain and Ireland: (108) Allhusen of Elswick Hall, Stoke Court and Bradenham Hall". Landed families of Britain and Ireland. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Hitachi Vantara – HDS partner contact information". HitachiVantara.com. 22 January 2021.

- ^ "International Group official website". igroup.co.uk. 22 January 2021.

- ^ Hammond, George; Raval, Anjli; Parkin, Benjamin (23 April 2021). "Mukesh Ambani buys 'Goldfinger' Stoke Park golf club for £57m". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "International Group – Founded in 1964, International Group is a family owned business". Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Servier Laboratories UK HQ Contact". Servier.co.uk. 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Urenco Ltd – Official website". Urenco.com. 22 January 2021.

- ^ Liddiard, E A G (1965). "The Fulmer Research Institute". Physics Bulletin. 16 (5): 161–169. doi:10.1088/0031-9112/16/5/001.

- ^ Macrae, T. F. (1957). "The Research Work of Glaxo Laboratories Limited". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 146 (923): 181–193. Bibcode:1957RSPSB.146..181M. doi:10.1098/rspb.1957.0003. ISSN 0080-4649. JSTOR 82979. PMID 13420142. S2CID 33221639.

- ^ "Stoke Poges West End Conservation Area". South Bucks District Council: 19. 19 July 2011.

- ^ "History". bayer.com. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Neighbourhood Statistics". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ^ "Britain's richest villages". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.