Supermarine Walrus

| Walrus | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Amphibious maritime patrol aircraft |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Supermarine |

| Designer | |

| Primary users | Royal Navy |

| Number built | 740 |

| History | |

| Manufactured | 1936–1944 |

| Introduction date | 1935 |

| First flight | 21 June 1933 |

| Developed from | Supermarine Seagull III |

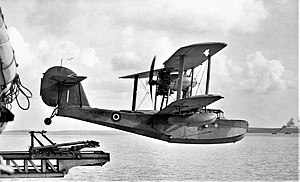

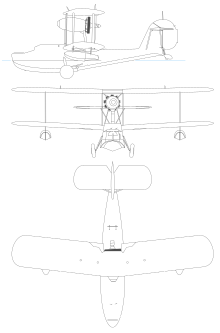

The Supermarine Walrus is a British single-engine amphibious biplane designed by Supermarine's R. J. Mitchell. Primarily used as a maritime patrol aircraft, it was the first British squadron-service aircraft to incorporate an undercarriage that was fully retractable, crew accommodation that was enclosed, and a fuselage completely made of metal.[1]

Supermarine originally named the type the Supermarine Seagull V, before changing it to the Walrus. The type first flew in 1933, its design process had begun four years earlier as a private venture. It shared its general arrangement with that of the earlier Supermarine Seagull. Having been designed to serve as a fleet spotter launched by catapult from cruisers or battleships, the aircraft was employed as a maritime patrol aircraft. Early aircraft had a metal hull for greater longevity in tropical conditions, while the later variant, the Supermarine Walrus II, had a wooden hull to conserve the use of light alloys.

The Supermarine Seagull V entered service with the Royal Australian Air Force in 1935. The type was subsequently adopted by the Fleet Air Arm, the Royal Air Force (RAF), the Royal New Zealand Navy, and the Royal New Zealand Air Force. Walruses operated against submarines throughout the Second World War, and were also used by the RAF Search and Rescue Force to recover personnel from the sea. It was intended to replace the Walrus with the more powerful Supermarine Sea Otter, but this did not happen. After the end of the war the Walrus continued in service, and some aircraft operated in a civil capacity in regions such as Australia and the Antarctic. The Walrus was succeeded in its air-sea rescue role by the first generation of helicopters.

Development

[edit]The Supermarine Walrus, originally called the Supermarine Seagull V, was initially developed by Supermarine as a private venture in response to a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) requirement for an observation seaplane to be catapult-launched from cruisers. Designed by a team led by Supermarine's chief designer, R.J. Mitchell, it resembled Mitchell's earlier Supermarine Seagull III in general layout.[2]

Supermarine began construction of a prototype during 1930, but due to other, more pressing, commitments did not complete it until 1933.[3][4] The prototype of the Seagull V, known as the Type 228, following modifications to the design, was first flown by "Mutt" Summers on 21 June 1933.[5] Five days later, the aeroplane (now marked N-1) made an appearance at the SBAC show at Hendon, where Summers made an unscheduled loop during the display, startling the spectators (Mitchell included).[6][7][3]

On 29 July Supermarine handed the aircraft (re-marked as N-2) over to the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment at Felixstowe.[7] Over the following months extensive trials took place; including shipborne trials aboard the Renown-class battlecruiser HMS Repulse and the Queen Elizabeth-class battleship HMS Valiant carried out on behalf of the Royal Australian Navy.[3] There were also catapult trials carried out by the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough,[8] when the Seagull V became the first piloted aircraft in the world to be launched by catapult, piloted by Flight Lieutenant Sydney Richard Ubee.[9]

The strength of the aircraft was demonstrated in October 1935, when a Seagull V carrying the Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet, Roger Backhouse, landed in the water in Portland Harbour with its wheels unretracted. The aircraft's hull flooded following the impact of the landing, which caused it to flip over, but Backhouse and the crew managed to escape with minor injuries. An automatic horn and indicator lights were subsequently fitted to ensure the pilot checked the wheels before landing.[3][10] The machine was later repaired and returned to service.[11] Soon afterwards it became one of the first aircraft to be fitted with an undercarriage position indicator on the instrument panel.[12] Test pilot Alex Henshaw later stated that the Walrus was strong enough to make a wheels-up landing on grass without much damage, but also commented that it was "the noisiest, coldest and most uncomfortable" aircraft he had ever flown.[13]

Design

[edit]Airframe

[edit]The Type 236 Supermarine Walrus is a single-engine amphibious biplane,[14] principally designed to conduct maritime observation missions. The all-metal hull, an innovation for its day, was constructed from an anodised alloy, with stainless steel forgings for the catapult spools and mountings. Metal construction was used because experience had shown that wooden structures deteriorated rapidly under tropical conditions.[3][1][15]

Although the aircraft typically flew with one pilot, there were positions for two.[16] The control column was not fixed, but could be inserted in either of two sockets in the floor, so that the column could be passed between the pilots.[3] Behind the cockpit there is a small cabin with work stations for the navigator and radio operator.[9]

Wings

[edit]The fabric-covered wings are of equal span, with a noticeable sweepback,[17] and have stainless–steel spars and wooden ribs.[18] The lower wings are set in the shoulder position with a stabilising float mounted under each one. The elevators are high on the tail-fin and braced by a pair of struts on either side . The wings can be folded, giving a stowage width a little greater than that of the tailplane.[19]

The Seagull V was the first British military aircraft to be fitted with a retractable undercarriage. A senior technical assistant at Supermarine suggested the idea of completely retracting the wheels into the wings, so as to make the aircraft more streamlined.[20]

Powerplant

[edit]

The single Bristol Pegasus radial engine[21] is mounted at the rear of a nacelle mounted on four struts above the lower wing and braced by four shorter struts to the centre-section of the upper wing.[3] This drives a four-bladed wooden pusher propeller. The nacelle contains the oil tank, arranged around an air intake at the front to act as an oil cooler, as well as electrical equipment, and has a number of access panels for maintenance. A supplementary oil cooler is mounted on the starboard side. Fuel is carried in two tanks in the upper wings.[16]

The Seagull's pusher configuration[15] has the advantages of keeping the engine and propeller out of the way of spray when operating on water and of reducing the noise level inside the aircraft; also the propeller was safely away from a crew member standing on the front deck when hooking on a hoisting cable.[16] The engine is offset by three degrees to starboard to counter any tendency of the aircraft to yaw due to unequal forces on the rudder caused by the vortex from the propeller.[3][15] A solid aluminium tailwheel is enclosed by a small water-rudder.[22]

Armament

[edit]The armament consisted of a pair of .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers K machine guns, one each in the open positions in the nose and rear fuselage.[19] In addition, there were provisions for carrying either bombs or depth charges mounted beneath the lower wings.[3][23]

Operation from ships

[edit]

Prior to the 1930s, aircraft catapults had been installed in any naval ship capable of launching an aircraft; by 1934, 25% of the FAA's aircraft were catapult-launched. When flying from a warship the Walrus would be recovered by touching-down alongside, then lifted from the sea by a ship's crane. The Walrus lifting gear was kept in a compartment in the section of wing directly above the engine. A crew member would climb onto the top wing and attach this to the crane hook.[15]

Landing and recovery was a straightforward procedure in calm waters, but could be difficult if the conditions were rough.[15] The usual procedure was for the parent ship to turn through around 20° just before the aircraft touched down, creating a 'slick' to the lee side of ship on which the Walrus could alight, this being followed by a fast taxi up to the ship before the 'slick' dissipated.[24][3]

Like other flying boats, the Walrus carried marine equipment for use on the water, including an anchor and a boat-hook.[25]

Production

[edit]

The RAAF ordered 24 Seagull Vs in 1933, to use as spotter-reconnaissance aircraft for the RAN. These were delivered during 1935 and 1936, with most of the aircraft being transported to Point Cook, Victoria, for use by the Seaplane Training Flight RAAF.[26]

The first order for 12 aircraft for the RAF was placed in May 1935; the first production aircraft, serial number K5772, flying on 16 March 1936.[27] In RAF service the type was named Walrus and initial production aircraft were powered by the Pegasus II M2, while from 1937 the 750 hp (560 kW) Pegasus VI was fitted. Production aircraft differed in minor details from the prototype; the transition between the upper decking and the aircraft sides was rounded off, the three struts bracing the tailplane were reduced to two, the trailing edges of the lower wing were hinged to fold 90° upwards rather than 180° downwards, and the external oil cooler was omitted.[28]

A total of 740 Walruses were built in three major variants: the Seagull V, Walrus I and Walrus II. Of these, 462 aircraft were constructed by Saunders-Roe in Weybridge, Surrey,[29][30] with fuselages built by Elliotts of Newbury.[31] This variant had a wooden hull, which was heavier but economised on the use of light alloys. Saunders-Roe license-built 270 metal Mark Is and 191 wooden-hulled Mark IIs.[32] The Walrus was called the "Shagbat", the "Steam Pigeon", and other names by its crews.[33][3]

The successor to the Walrus was the Sea Otter, which was similar in design but more powerful. Sea Otters never completely replaced the Walrus,[3] and both were used for air-sea rescue during the latter part of World War II. A post-war replacement for both aircraft, the Seagull, was cancelled in 1952, with only prototypes being constructed. By that time, air-sea rescue helicopters were taking over the role from small flying-boats.[34]

Operational history

[edit]Initial use

[edit]The first Seagull V, A2-1, was handed over to the Royal Australian Air Force in 1935, with the last being delivered in 1937.[35] The type served aboard the County-class cruisers HMAS Australia and Canberra, and the Leander-class cruisers Sydney, Perth and Hobart.[36][3]

Walrus deliveries to the RAF started in 1936 when the first example to be deployed was assigned to the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy, on Achilles[37]—one of the Leander-class light cruisers that carried one Walrus each.[36][38] The Royal Navy Town-class cruisers carried two Walruses during the Second World War,[39] and Walruses also equipped the York-class and County-class heavy cruisers.[40][41] Some battleships, such as the Queen Elizabeth-class battleship HMS Warspite and the Nelson-class battleship Rodney carried Walruses, as did the seaplane tender HMAS Albatross.[42][43]

By the start of the war, the Walrus was already in widespread use. Although its principal intended use was gunnery spotting in naval actions, this only occurred twice: Walruses from the battlecruiser Renown (the lead ship of her class) and the Town-class cruiser Manchester were launched in the Battle of Cape Spartivento,[3] and a Walrus from the Town-class Gloucester was used in the Battle of Cape Matapan.[44] The main task of ship-based aircraft was patrolling for Axis submarines and surface-raiders. By March 1941, Walruses were being deployed with ASV radar systems to assist in this.[45] During the Norwegian Campaign and the East African Campaign, Walruses saw limited use in bombing and strafing shore targets.[46] In August 1940, a Walrus operating from HMAS Hobart bombed and machine-gunned the Italian headquarters at Zeila in British Somaliland.[3][47]

By 1943, catapult-launched aircraft on cruisers and battleships were being replaced by radar, which occupied far less space on a warship. Walruses continued to fly from Royal Navy carriers for air-sea rescue and general communications. The low landing speed of the Walrus meant they could make a carrier landing despite having no flaps or tailhook.[48]

Other military uses

[edit]

The Walrus was used by the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force for air-sea rescue missions. The specialist RAF Air Sea Rescue Service squadrons flew a variety of aircraft, using Spitfires and Boulton Paul Defiants to patrol for downed aircrew, Avro Ansons to drop supplies and dinghies and Walruses to pick up them up from the water.[49] RAF air-sea rescue squadrons were deployed to cover the waters around the United Kingdom, the Mediterranean Sea and the Bay of Bengal.[50] Over 1000 aircrew were picked up during these operations, with 277 Squadron responsible for 598 rescues.[51]

In 1939, two Walruses were used at Lee-on-Solent for ASV trials,[3] with the dipole antennae fixed on the aircraft's interplane struts. In 1940, a Walrus was fitted with a forward-firing Oerlikon 20 mm cannon, intended as a counter-measure against German submarines. The gun was operated successfully, but the idea was abandoned when it was found that the flash blinded the pilot.[52]

A Walrus was shipped to Arkhangelsk with other supplies brought on the British Convoy PQ 17. It was supplied to the 16th air transport detachment, and flew to the end of 1943.[53]

After the war, Walruses continued to see limited military use with the RAF and foreign navies. Eight aircraft were operated by Argentina, with two flying from the cruiser La Argentina until 1958.[3] Other aircraft were used for training by the French Navy's Aviation navale.[54]

Post-war civilian use

[edit]A Supermarine Walrus was used experimentally in the 1940s by a whaling company, United Whalers. Operating in the Antarctic Ocean,[55] it was launched from the factory ship Balaena, which was equipped with a surplus naval catapult.[54] The aircraft used were fitted with sockets to power the electrically-heated suits worn by the crew under their immersion suits.[3] A cabin heater was fitted in the aircraft to help keep the crews warm during flights that could last over five hours.[56] A Dutch whaling company embarked Walruses, but never flew them.[54]

Four Walruses were bought from the RAAF by Amphibious Airways of Rabaul. Licensed to carry up to ten passengers, they were used for charter and air ambulance work, remaining in service until 1954.[3][57] During the first part of the 1960s, the remaining Walrus A2-4, registered for both private use and charter work, was provided with improved radio equipment and additional passengers seating. It was used to transport tourists and cargo out to the Great Barrier Reef and along the eastern coast of Australia.[58]

Variants

[edit]- Seagull V

- Original metal-hull version. Production—27 aircraft.[57]

- Walrus I

- Metal-hull version. Production by Supermarine—281 aircraft:[57]

- Walrus II

- Wooden-hull version. Production by Saunders-Roe—270 aircraft.[57]

Operators

[edit]Military operators

[edit]- Royal New Zealand Air Force

- No. 5 Squadron RNZAF

- Seaplane Training Flight

- Royal New Zealand Navy

- Royal Navy – Fleet Air Arm (FAA)[66]

- 700 Naval Air Squadron

- 701 Naval Air Squadron

- 702 Naval Air Squadron

- 710 Naval Air Squadron

- 711 Naval Air Squadron

- 712 Naval Air Squadron

- 714 Naval Air Squadron

- 715 Naval Air Squadron

- 718 Naval Air Squadron

- 720 Naval Air Squadron

- 737 Naval Air Squadron

- 743 Naval Air Squadron

- 749 Naval Air Squadron

- 754 Naval Air Squadron

- 764 Naval Air Squadron

- 765 Naval Air Squadron

- 773 Naval Air Squadron

- 777 Naval Air Squadron

- 779 Naval Air Squadron

- 789 Naval Air Squadron

- 810 Naval Air Squadron

- 820 Naval Air Squadron

- 1700 Naval Air Squadron

- 1701 Naval Air Squadron

- Royal Air Force

- No. 3 Squadron RAF[59]

- No. 89 Squadron RAF

- No. 91 Squadron RAF[59]

- No. 198 Squadron RAF[59]

- No. 269 Squadron RAF

- No. 275 Squadron RAF[59]

- No. 276 Squadron RAF[59]

- No. 277 Squadron RAF[59]

- No. 278 Squadron RAF

- No. 281 Squadron RAF

- No. 282 Squadron RAF

- No. 283 Squadron RAF

- No. 284 Squadron RAF

- No. 288 Squadron RAF[59]

- No. 292 Squadron RAF

- No. 293 Squadron RAF[59]

- No. 294 Squadron RAF

- No. 624 Squadron RAF

Civilian operators

[edit]- Kenting Aviation[67]

- Two aircraft were embarked on board of whaling ship Willem Barentsz.[68]

Surviving aircraft

[edit]Three examples of the Walrus survive in museums, in addition to a single privately-owned aircraft. Wreckage that is thought to be that of the Walrus assigned to the cruiser HMAS Sydney was photographed when the wreck of the vessel was rediscovered in 2008.[70]

Seagull V A2-4

[edit]

One of the original Australian Seagull Vs, A2-4 is on permanent display at the Royal Air Force Museum London. Built at Woolston in 1934, it arrived in Australia in early 1936, where it was initially allocated to No. 101 Flight RAAF (shortly afterwards becoming No. 5 Squadron RAAF). The aircraft had various pre-war duties, including survey work and flying from HMAS Sydney. It served for most of the war with No. 9 Squadron RAAF in Australia.[71]

In 1946, A2-4 was sold to civilian owners, and five years later was allocated the civil registration VH–ALB. During the 1950s and 1960s, it was flown by various Australian private owners before being badly damaged in a take-off accident at Taree, New South Wales in 1970. The wrecked aeroplane was acquired by the RAF Museum in exchange for a Supermarine Spitfire and a cash payment of Australian $5,000.[71][note 1] In 1973, en route the United Kingdom, it had to be fumigated in Hawaii, due to the discovery of Black widow spiders. The restoration of A2-4 began after its arrival at RAF Henlow; it has been on display at Royal Air Force Museum London since 1979.[71]

Walrus HD874

[edit]

HD874 is kept at the Royal Australian Air Force Museum at RAAF Williams Point Cook, Victoria.[72] It was originally flown by the Fleet Air Arm, before being transferred to the Royal Australian Air Force in 1943. During the war, HD874 was flown by the RAAF's No. 9 Squadron and No. 8 Communication Unit. [73]

Post-war, it was placed in storage until 1947, when it was issued to the RAAF's Antarctic flight, for use on Heard Island during the first Australian expedition to Antarctica since World War II. It was painted bright yellow. The Antarctic Flight only flew it once before it was badly damaged by a storm. It was recovered in 1980, and restored between 1993 and 2002.[73]

Walrus L2301

[edit]

The Walrus displayed at the Fleet Air Arm Museum at RNAS Yeovilton is a composite aircraft, constructed using the fuselage and engine of Walrus L2301. Built in 1939, L2301 was delivered to the Irish Air Corps, where it carried the Irish designation N.18. During its delivery flight on 3 March 1939, it suffered engine failure and later hull damage from ditching into the sea. It was towed to the old launch strip for the Curtiss H-16s at the former U.S. Naval Air Station Wexford Ireland.[74] L2301 was one of three Walruses (the other two being N.19 (L2302) and N.20 (L2303)) that were sent in March 1939 to the Irish Air Corps as maritime patrol aircraft during the Irish Emergency.[3][50]

On 9 January 1942 N.18 was stolen by four Irish nationals who intended to fly to France to join the Luftwaffe. However, they were intercepted by RAF Spitfires and escorted to RAF St Eval; the aircraft and its occupants were returned to Ireland.[3][74]

After the war, N.18 was transferred to Aer Lingus and given the Irish civil registration EI-ACC. However, the Irish airline never flew it and instead sold it to Wing Commander Ronald Gustave Kellett in 1946 for £150.[3] It was given the British civilian registration G-AIZG and flown until 1949 by members of No. 615 Squadron RAF for recreation.[74] In 1963 it was recovered from a dump at Haddenham airfield, where RAF Thame had been based,[75] by FAA crew from HMS Heron. They presented it to the Fleet Air Arm Museum, who restored it between 1964 and 1966.[3][74]

Walrus W2718

[edit]

After wartime RAF service, Walrus W2718 was operated by Somerton Airways on the Isle of Wight, until it was decommissioned in 1947. It was subsequently used as a caravan.[69] It became part of the collection of Solent Sky,[76] an aviation museum in Southampton, UK, where work was begun on restoring the aircraft to flying condition.

After being resold, restoration work was restarted in 2011 at Vintage Fabrics, Audley End, Essex. In 2018, after the aircraft was sold again to a private owner, it was moved to the Aircraft Restoration Company at Duxford Aerodrome.[69]

Specifications (Supermarine Walrus I)

[edit]

Data from Supermarine aircraft since 1914,[77] Supermarine Walrus I & Seagull V Variants[78]

General characteristics

- Crew: 3

- Length: 37 ft 7 in (11.46 m) on wheels

- Wingspan: 45 ft 10 in (13.97 m)

- Height: 15 ft 3 in (4.65 m) on wheels

- Wing area: 610 sq ft (57 m2)

- Empty weight: 4,900 lb (2,223 kg)

- Gross weight: 7,200 lb (3,266 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 8,050 lb (3,651 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Bristol Pegasus VI 9-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engine, 750 hp (560 kW)

- Propellers: 4-bladed wooden fixed-pitch pusher propeller

Performance

- Maximum speed: 135 mph (217 km/h, 117 kn) at 4,750 ft (1,448 m)

- Cruise speed: 92 mph (148 km/h, 80 kn) * Alighting speed: 57 mph (50 kn; 92 km/h)

- Range: 600 mi (970 km, 520 nmi) at cruise

- Service ceiling: 18,500 ft (5,600 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,050 ft/min (5.3 m/s)

- Time to altitude: 10,000 ft (3,000 m) in 12 minutes 30 seconds

- Wing loading: 11.8 lb/sq ft (58 kg/m2)

- Power/mass: 0.094 hp/lb (0.155 kW/kg)

Armament

- Guns: 2 × .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers K machine guns (one in nose, one behind wings)

- Bombs: 6 × 100 lb (45 kg) bombs

- or 2 × 250 lb (110 kg) bombs

- or 2 × 250 lb (110 kg) Mk.VIII depth charges

See also

[edit]Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

- List of aircraft of World War II

- List of aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm

- List of aircraft of the Royal Air Force

- List of flying boats and floatplanes

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Brown 1971, p. 28.

- ^ Morgan & Burnett 1981, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Smith, Peter (2014). Combat Biplanes of World War II. United Kingdom: Pen & Sword. p. 716. ISBN 978-1783400546.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 141.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 142.

- ^ Mitchell 2002, p. 135.

- ^ a b Morgan & Burnett 1981, p. 14.

- ^ London 2003, p. 141.

- ^ a b "The Supermarine "Seagull"" Mark V: Bristol "Pegasus" Engine". Flight. Vol. 52, no. 2011. 29 March 1934. pp. 297–300. ISSN 0015-3710.

- ^ Nicholl 1966, pp. 15, 25–26.

- ^ Morgan & Burnett 1981, p. 16.

- ^ Mitchell 2002, p. 136.

- ^ Shelton, John (30 June 2012). "Mitchell's Walrus – 'he looped the bloody thing'". R J Mitchell and Supermarine. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ Brown 1971, pp. 3, 6.

- ^ a b c d e London 2003, p. 140.

- ^ a b c "The Supermarine "Seagull" Mark V". Flight. 29 March 1934. p. 297–300. ISSN 0015-3710.

- ^ Marriott 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 144.

- ^ a b Brown 1971, p. 7.

- ^ Nicholl 1966, p. 15.

- ^ Brown 1971, p. 6.

- ^ Pegram 2016, p. 139.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, pp. 150, 155.

- ^ Nicholl 1966, p. 48.

- ^ Nicholl 1966, p. 20.

- ^ Brown 1971, p. 31.

- ^ Thetford 1994, p. 321.

- ^ Nicholl 1966, p. 29.

- ^ "Saunders Roe". BAE Systems. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 159.

- ^ London 1988, p. 31.

- ^ London 2003, p. 179.

- ^ Nicholl 1966, p. 34.

- ^ London 2003, p. 232.

- ^ Nicholl 1966, pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b Nicholl 1966, p. 67.

- ^ Nicholl 1966, p. 56.

- ^ "HMS Achilles". New Zealand History. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ Waters 2019, p. 313.

- ^ a b Nicholl 1966, p. 52.

- ^ Brown 2011, p. 8.

- ^ Ballantyne 2013, p. 81.

- ^ Nicholl 1966, pp. 66–67.

- ^ London 2003, p. 177.

- ^ London 2003, pp. 177, 182.

- ^ London 2003, p. 178.

- ^ "Italian Advance in Somaliland". The Times. No. 48691. London. 10 August 1942. p. 4.

- ^ London 2003, p. 181.

- ^ London 2003, p. 182.

- ^ a b London 2003, p. 183.

- ^ Nicholl 1966, p. 116.

- ^ Brown 1971, p. 34.

- ^ Kulikov, Viktor P. (2004). "British aircraft in Russia" (PDF). Air Power History. No. 1. Air Force Historical Foundation.

- ^ a b c London 2003, p. 213.

- ^ "Whaling Ship 'Balaena' Departs for Antarctic". British Pathé. 1946. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ Grierson, John (June 1947). "Air-Whaling" (PDF). Flight. Vol. 52, no. 2011. ISSN 0015-3710.

- ^ a b c d e Brown 1971, p. 47.

- ^ Simpson 2007, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nicholl 1966, p. 208.

- ^ London 2015, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b c Nicholl 1966, p. 182.

- ^ a b Nicholl 1966, p. 181.

- ^ Brown 1971, p. 40.

- ^ Kightly & Wallsgrove 2004, p. 116.

- ^ Spear 2023, p. 327.

- ^ Brown 1971, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Kightly & Wallsgrove 2004, p. 128.

- ^ "Walk Around – Supermarine Seagull / Walrus". International Plastic Modellers' Society Nederland. 12 March 2020. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Fiddian, Paul (1 May 2018). "Walrus Makes a Move". Pilot. Kelsey Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 4 May 2023.

- ^ "P09281.982". Australian War Mamorial. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d Simpson, Andrew (2007). "Individual History: Supermarine Seagull V A2-4/VH-ALB" (PDF). Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

- ^ Air Force History Branch 2021, p. 58.

- ^ a b "Supermarine Walrus HD 874". RAAF Museum Point Cook. 2010. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Supermarine Walrus (L2301)". Fleet Air Arm Museum. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Peter Chamberlain. "1945–1963". Haddenham Airfield: A history of a small Buckinghamshire airfield. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ "Over 20 aircraft to discover and explore". Solent Sky Museum. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, pp. 141–155.

- ^ Brown 1971, p. 48.

Sources

[edit]- Air Force History Branch (2021). Aircraft of The Royal Australian Air Force. Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-19224-8-804-6.

- Andrews, C. F.; Morgan, Eric B. (1981). Supermarine Aircraft since 1914. London: Putnam. ISBN 978-03701-0-018-0.

- Ballantyne, Iain (2013). Warspite, From Jutland Hero to Cold War Warrior. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84884-350-9.

- Brown, David (1971). Cain, Charles W. (ed.). Profile 224: Supermarine Walrus & Seagull Variants (PDF). Vol. 11. Windsor, UK: Profile Publications. OCLC 464172311.

- Brown, Les (2011). County Class Cruisers. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 978-18483-2-127-4.

- Kightly, James; Wallsgrove, Roger (2004). Supermarine Walrus & Stranraer. Sandomierz, Poland; Redbourn, UK.: Mushroom Model Publications. ISBN 978-83-917178-9-9.

- London, Peter M. (1988). Saunders & Saro Aircraft Since 1917. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-814-3.

- London, Peter M. (2003). British Flying Boats. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-2695-9.

- London, Peter M. (April 2015). "Aeroplane Database: Supermarine Walrus". Aeroplane.

- Marriott, Leo (2006). Catapult Aircraft: The Story of Seaplanes Flown from Battleships, Cruisers and Other Warships of the World's Navies, 1912–1950. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Aviation. ISBN 978-18441-5-419-7.

- Mitchell, Gordon (2002). R.J. Mitchell: Schooldays to Spitfire. London: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-3727-9.

- Morgan, Eric B.; Burnett, Charles (1981). "Walrus... amphibious angel of mercy". Air Enthusiast. No. 17. Stamford, UK: Pilot Press Ltd. pp. 13–25. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Nicholl, George William Robert (1966). The Supermarine Walrus: The Story of a Unique Aircraft (PDF). London: G.T. Foulis. OCLC 562476296.

- Pegram, Ralph (2016). Beyond the Spitfire: The Unseen Designs of R.J. Mitchell. Cheltenham, UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-6515-6.

- Spear, Joanna (2023). The Business of Armaments: Armstrongs, Vickers and the International Arms Trade, 1855-1955. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-10092-9-752-3.

- Thetford, Owen (1994). British Naval Aircraft Since 1912. London: Putnam. ISBN 978-0-85177-861-7.

- Waters, Conrad (2019). British Town Class Cruisers: Design, Development and Performance: Southampton and Belfast Classes. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 978-15267-1-888-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Franks, Norman (2017). The RAF Air-Sea Rescue Service in the Second World War. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 978-14738-6-130-5.

- Lezon, Ricardo Martin & Stitt, Robert M. (January–February 2004). "Eyes of the Fleet: Seaplanes in Argentine Navy Service, Part 2". Air Enthusiast. No. 109. pp. 46–59. ISSN 0143-5450.

External links

[edit]- Flying the Supermarine Walrus by Flt Lt Nick Berryman (self-published)

- A 2013 picture of the privately owned Walrus, G/RNLI.

- The Walrus in action – a 1935 news clip from British Movietone

- Information about the Supermarine Seagull V from the Royal Australian Navy website

- Further information and other images from Naval Encyclopedia