Fax

Fax (short for facsimile), sometimes called telecopying or telefax (short for telefacsimile), is the telephonic transmission of scanned printed material (both text and images), normally to a telephone number connected to a printer or other output device. The original document is scanned with a fax machine (or a telecopier), which processes the contents (text or images) as a single fixed graphic image, converting it into a bitmap, and then transmitting it through the telephone system in the form of audio-frequency tones. The receiving fax machine interprets the tones and reconstructs the image, printing a paper copy.[1] Early systems used direct conversions of image darkness to audio tone in a continuous or analog manner. Since the 1980s, most machines transmit an audio-encoded digital representation of the page, using data compression to transmit areas that are all-white or all-black, more quickly.

Initially a niche product, fax machines became ubiquitous in offices in the 1980s and 1990s.[2] However, they have largely been rendered obsolete by Internet-based technologies such as email and the World Wide Web, but are still used in some medical administration and law enforcement settings.[3]

History

[edit]Wire transmission

[edit]Scottish inventor Alexander Bain worked on chemical-mechanical fax-type devices and in 1846 Bain was able to reproduce graphic signs in laboratory experiments. He received British patent 9745 on May 27, 1843, for his "Electric Printing Telegraph".[4][5][6] Frederick Bakewell made several improvements on Bain's design and demonstrated a telefax machine.[7][8][9] The Pantelegraph was invented by the Italian physicist Giovanni Caselli.[10] He introduced the first commercial telefax service between Paris and Lyon in 1865, some 11 years before the invention of the telephone.[11][12]

In 1880, English inventor Shelford Bidwell constructed the scanning phototelegraph that was the first telefax machine to scan any two-dimensional original, not requiring manual plotting or drawing.[13] An account of Henry Sutton's "telephane" was published in 1896. Around 1900, German physicist Arthur Korn invented the Bildtelegraph, widespread in continental Europe especially following a widely noticed transmission of a wanted-person photograph from Paris to London in 1908,[14] used until the wider distribution of the radiofax.[15][16][17] Its main competitors were the Bélinographe by Édouard Belin first, then since the 1930s the Hellschreiber, invented in 1929 by German inventor Rudolf Hell, a pioneer in mechanical image scanning and transmission.[18]

The 1888 invention of the telautograph by Elisha Gray marked a further development in fax technology, allowing users to send signatures over long distances, thus allowing the verification of identification or ownership over long distances.[19][20][21]

On May 19, 1924, scientists of the AT&T Corporation "by a new process of transmitting pictures by electricity" sent 15 photographs by telephone from Cleveland to New York City, such photos being suitable for newspaper reproduction. Previously, photographs had been sent over the radio using this process.[22]

The Western Union "Deskfax" fax machine, announced in 1948, was a compact machine that fit comfortably on a desktop, using special spark printer paper.[23]

Wireless transmission

[edit]

As a designer for the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), in 1924, Richard H. Ranger invented the wireless photoradiogram, or transoceanic radio facsimile, the forerunner of today's "fax" machines. A photograph of President Calvin Coolidge sent from New York to London on November 29, 1924, became the first photo picture reproduced by transoceanic radio facsimile. Commercial use of Ranger's product began two years later. Also in 1924, Herbert E. Ives of AT&T transmitted and reconstructed the first color facsimile, a natural-color photograph of silent film star Rudolph Valentino in period costume, using red, green and blue color separations.[24]

Beginning in the late 1930s, the Finch Facsimile system was used to transmit a "radio newspaper" to private homes via commercial AM radio stations and ordinary radio receivers equipped with Finch's printer, which used thermal paper. Sensing a new and potentially golden opportunity, competitors soon entered the field, but the printer and special paper were expensive luxuries, AM radio transmission was very slow and vulnerable to static, and the newspaper was too small. After more than ten years of repeated attempts by Finch and others to establish such a service as a viable business, the public, apparently quite content with its cheaper and much more substantial home-delivered daily newspapers, and with conventional spoken radio bulletins to provide any "hot" news, still showed only a passing curiosity about the new medium.[25]

By the late 1940s, radiofax receivers were sufficiently miniaturized to be fitted beneath the dashboard of Western Union's "Telecar" telegram delivery vehicles.[23]

In the 1960s, the United States Army transmitted the first photograph via satellite facsimile to Puerto Rico from the Deal Test Site using the Courier satellite.

Radio fax is still in limited use today for transmitting weather charts and information to ships at sea. The closely related technology of slow-scan television is still used by amateur radio operators.

Telephone transmission

[edit]

| External images | |

|---|---|

In 1964, Xerox Corporation introduced (and patented) what many consider to be the first commercialized version of the modern fax machine, under the name (LDX) or Long Distance Xerography. This model was superseded two years later with a unit that would set the standard for fax machines for years to come. Up until this point facsimile machines were very expensive and hard to operate. In 1966, Xerox released the Magnafax Telecopiers, a smaller, 46 lb (21 kg) facsimile machine. This unit was far easier to operate and could be connected to any standard telephone line. This machine was capable of transmitting a letter-sized document in about six minutes. The first sub-minute, digital fax machine was developed by Dacom, which built on digital data compression technology originally developed at Lockheed for satellite communication.[26][27]

By the late 1970s, many companies around the world (especially Japanese firms) had entered the fax market. Very shortly after this, a new wave of more compact, faster and efficient fax machines would hit the market. Xerox continued to refine the fax machine for years after their ground-breaking first machine. In later years it would be combined with copier equipment to create the hybrid machines we have today that copy, scan and fax. Some of the lesser known capabilities of the Xerox fax technologies included their Ethernet enabled Fax Services on their 8000 workstations in the early 1980s.

Prior to the introduction of the ubiquitous fax machine, one of the first being the Exxon Qwip[28] in the mid-1970s, facsimile machines worked by optical scanning of a document or drawing spinning on a drum. The reflected light, varying in intensity according to the light and dark areas of the document, was focused on a photocell so that the current in a circuit varied with the amount of light. This current was used to control a tone generator (a modulator), the current determining the frequency of the tone produced. This audio tone was then transmitted using an acoustic coupler (a speaker, in this case) attached to the microphone of a common telephone handset. At the receiving end, a handset's speaker was attached to an acoustic coupler (a microphone), and a demodulator converted the varying tone into a variable current that controlled the mechanical movement of a pen or pencil to reproduce the image on a blank sheet of paper on an identical drum rotating at the same rate.

Computer facsimile interface

[edit]In 1985, Hank Magnuski, founder of GammaLink, produced the first computer fax board, called GammaFax. Such boards could provide voice telephony via Analog Expansion Bus.[29]

In the 21st century

[edit]

Although businesses usually maintain some kind of fax capability, the technology has faced increasing competition from Internet-based alternatives. In some countries,[which?] because electronic signatures on contracts are not yet recognized by law, while faxed contracts with copies of signatures are, fax machines enjoy continuing support in business.[31] In Japan, faxes are still used extensively as of September 2020 for cultural and graphemic reasons.[clarification needed][32][33][34][35] They are available for sending to both domestic and international recipients from over 81% of all convenience stores nationwide. Convenience-store fax machines commonly print the slightly re-sized content of the sent fax in the electronic confirmation-slip, in A4 paper size.[36][37][38] Use of fax machines for reporting cases during the COVID-19 pandemic has been criticised in Japan for introducing data errors and delays in reporting, slowing response efforts to contain the spread of infections and hindering the transition to remote work.[39][40][41]

In many corporate environments, freestanding fax machines have been replaced by fax servers and other computerized systems capable of receiving and storing incoming faxes electronically, and then routing them to users on paper or via an email (which may be secured).[42] Such systems have the advantage of reducing costs by eliminating unnecessary printouts and reducing the number of inbound analog phone lines needed by an office.

The once ubiquitous fax machine has also begun to disappear from the small office and home office environments.[citation needed] Remotely hosted fax-server services are widely available from VoIP and e-mail providers allowing users to send and receive faxes using their existing e-mail accounts without the need for any hardware or dedicated fax lines. Personal computers have also long been able to handle incoming and outgoing faxes using analog modems or ISDN, eliminating the need for a stand-alone fax machine. These solutions are often ideally suited for users who only very occasionally need to use fax services. In July 2017 the United Kingdom's National Health Service was said to be the world's largest purchaser of fax machines because the digital revolution has largely bypassed it.[43] In June 2018 the Labour Party said that the NHS had at least 11,620 fax machines in operation[44] and in December the Department of Health and Social Care said that no more fax machines could be bought from 2019 and that the existing ones must be replaced by secure email by March 31, 2020.[45]

Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, generally viewed as digitally advanced in the NHS, was engaged in a process of removing its fax machines in early 2019. This involved quite a lot of e-fax solutions because of the need to communicate with pharmacies and nursing homes which may not have access to the NHS email system and may need something in their paper records.[46]

In 2018 two-thirds of Canadian doctors reported that they primarily used fax machines to communicate with other doctors. Faxes are still seen as safer and more secure and electronic systems are often unable to communicate with each other.[47]

Hospitals are the leading users for fax machines in the United States where some doctors prefer fax machines over emails, often due to concerns about accidentally violating HIPAA.[3]

Capabilities

[edit]There are several indicators of fax capabilities: group, class, data transmission rate, and conformance with ITU-T (formerly CCITT) recommendations. Since the 1968 Carterfone decision, most fax machines have been designed to connect to standard PSTN lines and telephone numbers.

Group

[edit]Analog

[edit]Group 1 and 2 faxes are sent in the same manner as a frame of analog television, with each scanned line transmitted as a continuous analog signal. Horizontal resolution depended upon the quality of the scanner, transmission line, and the printer. Analog fax machines are obsolete and no longer manufactured. ITU-T Recommendations T.2 and T.3 were withdrawn as obsolete in July 1996.

- Group 1 faxes conform to the ITU-T Recommendation T.2. Group 1 faxes take six minutes to transmit a single page, with a vertical resolution of 96 scan lines per inch. Group 1 fax machines are obsolete and no longer manufactured.

- Group 2 faxes conform to the ITU-T Recommendations T.3 and T.30. Group 2 faxes take three minutes to transmit a single page, with a vertical resolution of 96 scan lines per inch. Group 2 fax machines are almost obsolete, and are no longer manufactured. Group 2 fax machines can interoperate with Group 3 fax machines.

Digital

[edit]

A major breakthrough in the development of the modern facsimile system was the result of digital technology, where the analog signal from scanners was digitized and then compressed, resulting in the ability to transmit high rates of data across standard phone lines. The first digital fax machine was the Dacom Rapidfax first sold in late 1960s, which incorporated digital data compression technology developed by Lockheed for transmission of images from satellites.[26][27]

Group 3 and 4 faxes are digital formats and take advantage of digital compression methods to greatly reduce transmission times.

- Group 3 faxes conform to the ITU-T Recommendations T.30 and T.4. Group 3 faxes take between 6 and 15 seconds to transmit a single page (not including the initial time for the fax machines to handshake and synchronize). The horizontal and vertical resolutions are allowed by the T.4 standard to vary among a set of fixed resolutions:

- Horizontal: 100 scan lines per inch

- Vertical: 100 scan lines per inch ("Basic")

- Horizontal: 200 or 204 scan lines per inch

- Vertical: 100 or 98 scan lines per inch ("Standard")

- Vertical: 200 or 196 scan lines per inch ("Fine")

- Vertical: 400 or 391 (note not 392) scan lines per inch ("Superfine")

- Horizontal: 300 scan lines per inch

- Vertical: 300 scan lines per inch

- Horizontal: 400 or 408 scan lines per inch

- Vertical: 400 or 391 scan lines per inch ("Ultrafine")

- Horizontal: 100 scan lines per inch

- Group 4 faxes are designed to operate over 64 kbit/s digital ISDN circuits. They conform to the ITU-T Recommendations

- T.563 (Terminal characteristics for Group 4 facsimile apparatus),

- T.503 (Document application profile for the interchange of Group 4 facsimile documents),

- T.521 (Communication application profile BT0 for document bulk transfer based on the session service),

- T.6 (Facsimile coding schemes and coding control functions for Group 4 facsimile apparatus) specifying resolutions, a superset of the resolutions from T.4 [48],

- T.62 (Control procedures for teletex and Group 4 facsimile services),

- T.70 (Network-independent basic transport service for the telematic services), and

- T.411 to T.417 (concerned with aspects of the Open Document Architecture).

Fax Over IP (FoIP) can transmit and receive pre-digitized documents at near-realtime[vague] speeds using ITU-T recommendation T.38 to send digitised images over an IP network using JPEG compression. T.38 is designed to work with VoIP services and often supported by analog telephone adapters used by legacy fax machines that need to connect through a VoIP service. Scanned documents are limited to the amount of time the user takes to load the document in a scanner and for the device to process a digital file. The resolution can vary from as little as 150 DPI to 9600 DPI or more. This type of faxing is not related to the e-mail–to–fax service that still uses fax modems at least one way.

Class

[edit]Computer modems are often designated by a particular fax class, which indicates how much processing is offloaded from the computer's CPU to the fax modem.

- Class 1 (also known as Class 1.0) fax devices do fax data transfer, while the T.4/T.6 data compression and T.30 session management are performed by software on a controlling computer. This is described in ITU-T recommendation T.31.[49]

- What is commonly known as "Class 2" is an unofficial class of fax devices that perform T.30 session management themselves, but the T.4/T.6 data compression is performed by software on a controlling computer. Implementations of this "class" are based on draft versions of the standard that eventually significantly evolved to become Class 2.0.[50] All implementations of "Class 2" are manufacturer-specific.[51]

- Class 2.0 is the official ITU-T version of Class 2 and is commonly known as Class 2.0 to differentiate it from many manufacturer-specific implementations of what is commonly known as "Class 2". It uses a different but standardized command set than the various manufacturer-specific implementations of "Class 2". The relevant ITU-T recommendation is T.32.[51]

- Class 2.1 is an improvement of Class 2.0 that implements faxing over V.34 (33.6 kbit/s), which boosts faxing speed from fax classes "2" and 2.0, which are limited to 14.4 kbit/s.[51] The relevant ITU-T recommendation is T.32 Amendment 1.[51] Class 2.1 fax devices are referred to as "super G3".

Data transmission rate

[edit]Several different telephone-line modulation techniques are used by fax machines. They are negotiated during the fax-modem handshake, and the fax devices will use the highest data rate that both fax devices support, usually a minimum of 14.4 kbit/s for Group 3 fax.

ITU standard Released date Data rates (bit/s) Modulation method V.27 1988 4800, 2400 PSK V.29 1988 9600, 7200, 4800 QAM V.17 1991 14400, 12000, 9600, 7200 TCM V.34 1994 28800 QAM V.34bis 1998 33600 QAM ISDN 1986 64000 4B3T / 2B1Q (line coding)

"Super Group 3" faxes use V.34bis modulation that allows a data rate of up to 33.6 kbit/s.

Compression

[edit]As well as specifying the resolution (and allowable physical size) of the image being faxed, the ITU-T T.4 recommendation specifies two compression methods for decreasing the amount of data that needs to be transmitted between the fax machines to transfer the image. The two methods defined in T.4 are:[52]

- Modified Huffman (MH).

- Modified READ (MR) (Relative Element Address Designate[53]), optional.

An additional method is specified in T.6:[48]

- Modified Modified READ (MMR).

Later, other compression techniques were added as options to ITU-T recommendation T.30, such as the more efficient JBIG (T.82, T.85) for bi-level content, and JPEG (T.81), T.43, MRC (T.44), and T.45 for grayscale, palette, and colour content.[54] Fax machines can negotiate at the start of the T.30 session to use the best technique implemented on both sides.

Modified Huffman

[edit]Modified Huffman (MH), specified in T.4 as the one-dimensional coding scheme, is a codebook-based run-length encoding scheme optimised to efficiently compress whitespace.[52] As most faxes consist mostly of white space, this minimises the transmission time of most faxes. Each line scanned is compressed independently of its predecessor and successor.[52]

Modified READ

[edit]Modified READ, specified as an optional two-dimensional coding scheme in T.4, encodes the first scanned line using MH.[52] The next line is compared to the first, the differences determined, and then the differences are encoded and transmitted.[52] This is effective, as most lines differ little from their predecessor. This is not continued to the end of the fax transmission, but only for a limited number of lines until the process is reset, and a new "first line" encoded with MH is produced. This limited number of lines is to prevent errors propagating throughout the whole fax, as the standard does not provide for error correction. This is an optional facility, and some fax machines do not use MR in order to minimise the amount of computation required by the machine. The limited number of lines is 2 for "Standard"-resolution faxes, and 4 for "Fine"-resolution faxes.

Modified Modified READ

[edit]The ITU-T T.6 recommendation adds a further compression type of Modified Modified READ (MMR), which simply allows a greater number of lines to be coded by MR than in T.4.[48] This is because T.6 makes the assumption that the transmission is over a circuit with a low number of line errors, such as digital ISDN. In this case, the number of lines for which the differences are encoded is not limited.

JBIG

[edit]In 1999, ITU-T recommendation T.30 added JBIG (ITU-T T.82) as another lossless bi-level compression algorithm, or more precisely a "fax profile" subset of JBIG (ITU-T T.85). JBIG-compressed pages result in 20% to 50% faster transmission than MMR-compressed pages, and up to 30 times faster transmission if the page includes halftone images.

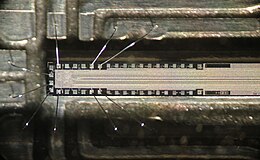

JBIG performs adaptive compression, that is, both the encoder and decoder collect statistical information about the transmitted image from the pixels transmitted so far, in order to predict the probability for each next pixel being either black or white. For each new pixel, JBIG looks at ten nearby, previously transmitted pixels. It counts, how often in the past the next pixel has been black or white in the same neighborhood, and estimates from that the probability distribution of the next pixel. This is fed into an arithmetic coder, which adds only a small fraction of a bit to the output sequence if the more probable pixel is then encountered.

The ITU-T T.85 "fax profile" constrains some optional features of the full JBIG standard, such that codecs do not have to keep data about more than the last three pixel rows of an image in memory at any time. This allows the streaming of "endless" images, where the height of the image may not be known until the last row is transmitted.

ITU-T T.30 allows fax machines to negotiate one of two options of the T.85 "fax profile":

- In "basic mode", the JBIG encoder must split the image into horizontal stripes of 128 lines (parameter L0 = 128) and restart the arithmetic encoder for each stripe.

- In "option mode", there is no such constraint.

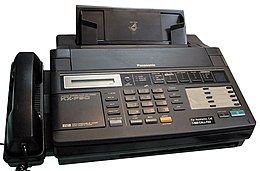

Matsushita Whiteline Skip

[edit]A proprietary compression scheme employed on Panasonic fax machines is Matsushita Whiteline Skip (MWS). It can be overlaid on the other compression schemes, but is operative only when two Panasonic machines are communicating with one another. This system detects the blank scanned areas between lines of text, and then compresses several blank scan lines into the data space of a single character. (JBIG implements a similar technique called "typical prediction", if header flag TPBON is set to 1.)

Typical characteristics

[edit]Group 3 fax machines transfer one or a few printed or handwritten pages per minute in black-and-white (bitonal) at a resolution of 204×98 (normal) or 204×196 (fine) dots per square inch. The transfer rate is 14.4 kbit/s or higher for modems and some fax machines, but fax machines support speeds beginning with 2400 bit/s and typically operate at 9600 bit/s. The transferred image formats are called ITU-T (formerly CCITT) fax group 3 or 4. Group 3 faxes have the suffix .g3 and the MIME type image/g3fax.

The most basic fax mode transfers in black and white only. The original page is scanned in a resolution of 1728 pixels/line and 1145 lines/page (for A4). The resulting raw data is compressed using a modified Huffman code optimized for written text, achieving average compression factors of around 20. Typically a page needs 10 s for transmission, instead of about three minutes for the same uncompressed raw data of 1728×1145 bits at a speed of 9600 bit/s. The compression method uses a Huffman codebook for run lengths of black and white runs in a single scanned line, and it can also use the fact that two adjacent scanlines are usually quite similar, saving bandwidth by encoding only the differences.

Fax classes denote the way fax programs interact with fax hardware. Available classes include Class 1, Class 2, Class 2.0 and 2.1, and Intel CAS. Many modems support at least class 1 and often either Class 2 or Class 2.0. Which is preferable to use depends on factors such as hardware, software, modem firmware, and expected use.

Printing process

[edit]Fax machines from the 1970s to the 1990s often used direct thermal printers with rolls of thermal paper as their printing technology, but since the mid-1990s there has been a transition towards plain-paper faxes: thermal transfer printers, inkjet printers and laser printers.

One of the advantages of inkjet printing is that inkjets can affordably print in color; therefore, many of the inkjet-based fax machines claim to have color fax capability. There is a standard called ITU-T30e (formally ITU-T Recommendation T.30 Annex E [55]) for faxing in color; however, it is not widely supported, so many of the color fax machines can only fax in color to machines from the same manufacturer.[citation needed]

Stroke speed

[edit]Stroke speed in facsimile systems is the rate at which a fixed line perpendicular to the direction of scanning is crossed in one direction by a scanning or recording spot. Stroke speed is usually expressed as a number of strokes per minute. When the fax system scans in both directions, the stroke speed is twice this number. In most conventional 20th century mechanical systems, the stroke speed is equivalent to drum speed.[56]

Fax paper

[edit]

As a precaution, thermal fax paper is typically not accepted in archives or as documentary evidence in some courts of law unless photocopied. This is because the image-forming coating is eradicable and brittle, and it tends to detach from the medium after a long time in storage.[57]

Fax tone

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2023) |

A CNG tone is an 1100 Hz tone transmitted by a fax machine when it calls another fax machine. Fax tones can cause complications when implementing fax over IP.

Internet fax

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

One popular alternative is to subscribe to an Internet fax service, allowing users to send and receive faxes from their personal computers using an existing email account. No software, fax server or fax machine is needed. Faxes are received as attached TIFF or PDF files, or in proprietary formats that require the use of the service provider's software. Faxes can be sent or retrieved from anywhere at any time that a user can get Internet access. Some services offer secure faxing to comply with stringent HIPAA and Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act requirements to keep medical information and financial information private and secure. Utilizing a fax service provider does not require paper, a dedicated fax line, or consumable resources.[58]

Another alternative to a physical fax machine is to make use of computer software which allows people to send and receive faxes using their own computers, utilizing fax servers and unified messaging. A virtual (email) fax can be printed out and then signed and scanned back to computer before being emailed. Also the sender can attach a digital signature to the document file.

With the surging popularity of mobile phones, virtual fax machines can now be downloaded as applications for Android and iOS. These applications make use of the phone's internal camera to scan fax documents for upload or they can import from various cloud services.

Related standards

[edit]- T.4 is the umbrella specification for fax. It specifies the standard image sizes, two forms of image-data compression (encoding), the image-data format, and references, T.30 and the various modem standards.

- T.6 specifies a compression scheme that reduces the time required to transmit an image by roughly 50-percent.

- T.30 specifies the procedures that a sending and receiving terminal use to set up a fax call, determine the image size, encoding, and transfer speed, the demarcation between pages, and the termination of the call. T.30 also references the various modem standards.

- V.21, V.27ter, V.29, V.17, V.34: ITU modem standards used in facsimile. The first three were ratified prior to 1980, and were specified in the original T.4 and T.30 standards. V.34 was published for fax in 1994.[59]

- T.37 The ITU standard for sending a fax-image file via e-mail to the intended recipient of a fax.

- T.38 The ITU standard for sending Fax over IP (FoIP).

- G.711 pass through - this is where the T.30 fax call is carried in a VoIP call encoded as audio. This is sensitive to network packet loss, jitter and clock synchronization. When using voice high-compression encoding techniques such as, but not limited to, G.729, some fax tonal signals may not be correctly transported across the packet network.

- RFC 3362 image/t38 MIME-type

- SSL Fax An emerging standard that allows a telephone based fax session to negotiate a fax transfer over the internet, but only if both sides support the standard. The standard is partially based on T.30 and is being developed by Hylafax+ developers.

See also

[edit]- 3D Fax

- Black fax

- Called subscriber identification (CSID)

- Error correction mode (ECM)

- Fax art

- Fax demodulator

- Fax modem

- Fax server

- Faxlore

- Fultograph

- Image scanner

- Internet fax

- Junk fax

- Radiofax—image transmission over HF radio

- Slow-scan television

- T.38 Fax-over-IP

- Telautograph

- Telex

- Teletex

- Transmitting Subscriber Identification (TSID)

- Wirephoto

References

[edit]- ^ Rouse, Margaret (June 2006). "What is fax?". SearchNetworking. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Shapiro, Carl; Varian, Hal R. (1999). Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy. Harvard Business Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-87584-863-1.

- ^ a b Haigney, Sophie (18 November 2018). "The Fax Is Not Yet Obsolete". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2018-11-18. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ (Staff) (20 April 1844). "Mr. Bain's electric printing telegraph". Mechanics' Magazine. 40 (1080): 268–270.

- ^ Bain, Alexander "Improvement in copying surfaces by electricity" Archived 2021-05-14 at the Wayback Machine U.S. patent no. 5,957 (5 December 1848).

- ^ Ruddock, Ivan S. (Summer 2012). "Alexander Bain: The real father of television?" (PDF). Scottish Local History (83): 3–13.

- ^ Bakewell, Frederick Collier "Electric telegraphs" English patent no. 12,352 (filed: 2 December 1848; issued: 2 June 1849).

- ^ Bakewell, F.C. (November 1851). "On the copying telegraph". American Journal of Science. 2nd series. 12: 278.

- ^ "1851 Great Exhibition: Official Catalogue: Class X.: Frederick Collier Bakewell".

- ^ Caselli, Giovanni "Improved pantographic telegraph" Archived 2021-05-14 at the Wayback Machine U.S. patent no. 20,698 (June 29, 1858).

- ^ "Istituto Tecnico Industriale, Italy. Italian biography of Giovanni Caselli". Itisgalileiroma.it. Archived from the original on 2020-08-17. Retrieved 2014-02-16.

- ^ "The Hebrew University of Jerusalem – Giovanni Caselli biography". Archived from the original on May 6, 2008.

- ^ See:

- Bidwell, Shelford (November 18, 1880). "The photophone". Nature. 23 (577): 58–59. Bibcode:1880Natur..23...58B. doi:10.1038/023058a0. S2CID 4127035.

- Bidwell, Shelford (February 10, 1881). "Tele-photography". Nature. 23 (589): 344–346. Bibcode:1881Natur..23..344B. doi:10.1038/023344a0.

- (Staff) (March 1, 1881). "Tele-photography". Telegraphic Journal and Electrical Review. 9: 82–84.

- ^ Korn, Arthur (1927). Die Bildtelegraphie im Dienste der Polizei [Tele-photography in service to the police] (in German). Graz, Austria: Ulrich Mosers Buchhandlung.

- ^ Korn, Arthur (1907). Elektrisches Fernphotograhie und Ähnliches [Electrical transmission of images and similar [systems]] (in German) (2nd ed.). Leipzig, Germany: S. Hirzel.

- ^ Korn, Arthur (14 December 1905). "Elektrische Fernphotographie" [Electrical tele-photography]. Elektrotechnische Zeitschrift (in German). 26 (50): 1131–1134.

- ^ Korn, A. (1904). "Uber Gebe- und Empfangsapparate zur elektrischen Fernubertragung von Photographien" [On transmitting and receiving apparatuses for the electrical transmission of photographs]. Physikalische Zeitschrift (in German). 5 (4): 113–118.

- ^ "Edouard Belin - Belinograph Inventor". Fax Authority. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- ^ Gray, Elisha "Art of telegraphy" U.S. patent no. 386,814 (filed: May 31, 1888; issued: July 31, 1888).

- ^ Gray, Elisha "Telautography" U.S. patent no. 386,815 (filed: June 13, 1888; issued: July 31, 1888).

- ^ "The History of Fax – from 1843 to Present Day". Fax Authority. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ "Photos Sent Over Telephone Wire by Cleveland to N.Y.", The Gazette (Montreal), May 20, 1924, p.10

- ^ a b G. H. Ridings, A Facsimile transceiver for Pickup and Delivery of Telegrams Archived 2016-02-08 at the Wayback Machine, Western Union Technical Review, Vol. 3, No, 1 Archived 2016-03-10 at the Wayback Machine (January 1949); page 17-26.

- ^ Sipley, Louis Walton (1951). A Half Century of Color. Macmillan.

- ^ Schneider, John (2011). "The Newspaper of the Air: Early Experiments with Radio Facsimile". theradiohistorian.org. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- ^ a b c The implementation of a personal computer-based digital facsimile information distribution system Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine – Edward C. Chung, Ohio University, November 1991, page 2

- ^ a b Fax: The Principles and Practice of Facsimile Communication, Daniel M. Costigan, Chilton Book Company, 1971, pages 112–114, 213, 239

- ^ An Exxon Sale To Harris Unit – The New York Times, February 22, 1985.

- ^ Perratore, Ed (September 1992). "GammaFax MLCP-4/AEB: High-End Fax, Long-Range Potential". Byte. Vol. 17, no. 9. McGraw-Hill. pp. 82, 84. ISSN 0360-5280.

- ^ "Manual of fax machine Brother 8070, see 3rd page" (PDF).

- ^ Adams, Ken (7 November 2007). "Enforceability of Fax and Scanned Signature Pages". AdamsDrafting. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Michael (3 November 2015). "Why is hi-tech Japan using cassette tapes and faxes?". BBC News. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ Fackler, Martin (13 February 2013). "In High-Tech Japan, the Fax Machines Roll On (Published 2013)". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ "Low-tech Japan challenged in working from home amid pandemic". Mainichi Daily News. The Mainichi. 26 April 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ Osaki, Tomohiro (27 September 2020). "Taro Kono, Japan's administrative reform minister, declares war on faxes". The Japan Times. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ "FAXサービス|サービス|ローソン" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2015-02-10.

- ^ Fackler, Martin (13 February 2013). "In High-Tech Japan, the Fax Machines Roll On". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ^ Oi, Mariko (2012-07-31). "Japan and the fax: A love affair". BBC News. Retrieved 2014-02-16.

- ^ Osborne, Samuel (6 May 2020). "Japan's reliance on fax machines lambasted by coronavirus doctor". The Independent. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ Takahashi, Ryusei (4 August 2020). "Tokyo test centers trade fax machines for computers with new coronavirus reporting system". The Japan Times. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ "Online criticism of outdated paper-and-fax coronavirus infection reports spark change in Japan". Mainichi Daily News. The Mainichi. 2 May 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ Coopersmith, Jonathan (16 June 2021). "Faxing is old tech. So why is it also growing in popularity?". Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023.

- ^ "Digital doldrums: NHS remains world's largest purchaser of fax machines". National Health Executive. 5 July 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ "NHS 'Struggling To Keep Up' As It Holds On To Thousands Of Fax Machines". Huffington Post. 11 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ "NHS told to ditch 'absurd' fax machines". BBC. 9 December 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ Hill, Rebecca (4 February 2019). "OK, it's early 2019. Has Leeds Hospital finally managed to 'axe the fax'? Um, yes and no". The Register. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "Why are fax machines still the norm in 21st-century health care?". Globe and Mail. 11 June 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ a b c "T.6: Facsimile coding schemes and coding control functions for Group 4 facsimile apparatus". ITU-T. November 1988. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ^ Peterson, Kerstin Day (2000). Business telecom systems: a guide to choosing the best technologies and services. Focal Press. pp. 191–192. ISBN 1578200415. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- ^ "Supra Technical Support Bulletin: Class 2 Fax Commands For Supra Faxmodems". June 19, 1992. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Fax Developer's Guide: Classes 2 and 2.0/2.1" (PDF). Multi-Tech Systems. 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "T.4: Standardization of Group 3 facsimile terminals for document transmission". ITU-T. 2011-03-14. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ^ Hunter, R.; Robinson, A.H. (1980). "International digital facsimile coding standards". Proceedings of the IEEE. 68 (7): 854–867. doi:10.1109/PROC.1980.11751. S2CID 46403372.

- ^ "T.30: Procedures for document facsimile transmission in the general switched telephone network". ITU-T. 2014-05-15. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ^ tsbmail. "T.30 : Procedures for document facsimile transmission in the general switched telephone network". Itu.int. Retrieved 2014-02-16.

- ^

This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22. (in support of MIL-STD-188).

This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22. (in support of MIL-STD-188).

- ^ "4.12 Filing rules: 19.Newspaper extracts or thermal facsimile paper should not be preserved as archives. Such extracts should be photocopied and the copy preserved. The original can then be destroyed." Office of Corporate & Legal Affairs, University College Cork, Ireland

- ^ "Online Fax vs Traditional Fax". eFax. 16 May 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "V.34". www.itwissen.info. Archived from the original on 2016-12-28. Retrieved 2018-01-12.

Further reading

[edit]- Coopersmith, Jonathan, Faxed: The Rise and Fall of the Fax Machine (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015) 308 pp.

- "Transmitting Photographs by Telegraph", Scientific American article, 12 May 1877, p. 297

External links

[edit]- Group 3 Facsimile Communication—A '97 essay with technical details on compression and error codes, and call establishment and release.

- ITU T.30 Recommendation