Islam and blasphemy

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) |

|---|

|

| Islamic studies |

In Islam, blasphemy is impious utterance or action concerning God,[2] but is broader than in normal English usage, including not only the mocking or vilifying of attributes of Islam but denying any of the fundamental beliefs of the religion.[3] Examples include denying that the Quran was divinely revealed,[3] the Prophethood of one of the Islamic prophets,[4] insulting an angel, or maintaining God had a son.[3]

The Quran curses those who commit blasphemy and promises blasphemers humiliation in the Hereafter.[5] However, whether any Quranic verses prescribe worldly punishments is debated: some Muslims believe that no worldly punishment is prescribed while others disagree.[6][7] The interpretation of hadiths, which are another source of Sharia, is similarly debated.[8][6] Some have interpreted hadith as prescribing punishments for blasphemy, which may include death, while others argue that the death penalty applies only to cases where perpetrator commits treasonous crimes, especially during times of war.[9] Different traditional schools of jurisprudence prescribe different punishment for blasphemy, depending on whether the blasphemer is Muslim or non-Muslim, a man or a woman.[7]

In the modern Muslim world, the laws pertaining to blasphemy vary by country, and some countries prescribe punishments consisting of fines, imprisonment, flogging, hanging, or beheading.[10] Capital punishment for blasphemy was rare in pre-modern Islamic societies.[11] In the modern era some states and radical groups have used charges of blasphemy in an effort to burnish their religious credentials and gain popular support at the expense of liberal Muslim intellectuals and religious minorities.[12] Other Muslims instead push for greater freedom of expression.[12] Contemporary accusations of blasphemy against Islam have sparked international controversies and incited mob violence and assassinations.

Islamic scripture

[edit]In Islamic literature, blasphemy is of many types, and there are many different words for it: sabb (insult) and shatm (abuse, vilification), takdhib or tajdif (denial), iftira (concoction), la`n or la'ana (curse) and ta`n (accuse, defame).[13] In Islamic literature, the term "blasphemy" sometimes also overlaps with kufr ("unbelief"), fisq (depravity), isa'ah (insult), and ridda (apostasy).[14][2]

Quran

[edit]A number of verses in the Qur'an have been interpreted as relating to blasphemy. In these verses God admonishes those who commit blasphemy. Some verses are cited as evidence that the Qur'an does not prescribe punishments for blasphemy,[15] while other verses are cited as evidence that it does.

The only verse that directly says blasphemy (sabb) is Q6:108.[6] The verse calls on Muslims to not blaspheme against deities of other religions, lest people of that religion retaliate by blaspheming against Allah.[6]

And do not insult (wa la tasubbu) those they invoke other than Allah, lest they insult (fa-yasubbu) Allah in enmity without knowledge. Thus We have made pleasing to every community their deeds. Then to their Lord is their return, and He will inform them about what they used to do.

Verse 5:33 prescribes prison or mutilation or death for those "who wage war against Allah and His Messenger".[6] Even though the verse doesn't mention blasphemy (sabb), some commentators have used to justify punishments for blasphemy.[6][17] Other commentators believe this verse only applies to those who commit crimes against human life and property.[18]

The only punishment of those who wage war against Allah and His Messenger and strive to make mischief in the land is that they should be murdered, or crucified, or their hands and their feet should be cut off on opposite sides, or they should be imprisoned. This shall be a disgrace for them in this world, and in the Hereafter they shall have a grievous chastisement. Except those who repent before you overpower them; so know that Allah is Forgiving, Merciful.

33:57–61 have also been used by some commentators to justify blasphemy punishments.[19][20] However, other scholars opined that verses 33:57–61 could only have been acted upon during the life of the Prophet and since the demise of Muhammad they are no longer applicable.[6]

Other passages are not related to any earthly punishment for blasphemy, but prescribe Muslims to not "sit with" those who mock the religion[21][22] – although the latter are admonishments directed towards a witness of blasphemy rather than the guilty of blasphemy:

When you hear Allah's revelations disbelieved in and mocked at, do not sit with them until they enter into some other discourse; surely then you would be like them.

According to Shemeem Burney Abbas, the Qur'an mentions many examples of disbelievers ridiculing and mocking Muhammad, but never commands him to punish those who mocked him. Instead, the Qur'an asks Muhammad to leave the punishment of blasphemy to God, and that there would be justice in the afterlife.[15]

Hadith

[edit]According to several hadiths, Muhammad ordered a number of enemies executed "in the hours after Mecca's fall". One of those who was killed was Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf, because he had insulted Muhammad.[23]

The Prophet said, "Who is ready to kill Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf who has really hurt Allah and His Apostle?" Muhammad bin Maslama said, "O Allah's Apostle! Do you like me to kill him?" He replied in the affirmative. So, Muhammad bin Maslama went to him (i.e. Ka'b) and said, "This person (i.e. the Prophet) has put us to task and asked us for charity." Ka'b replied, "By Allah, you will get tired of him." Muhammad said to him, "We have followed him, so we dislike to leave him till we see the end of his affair." Muhammad bin Maslama went on talking to him in this way till he got the chance to kill him. Narrated Jabir bin 'Abdullah

It has been narrated on the authority of Jabir that the Messenger of Allah said: Who will kill Ka'b b. Ashraf? He has maligned Allah, the Exalted, and His Messenger. Muhammad b. Maslama said: Messenger of Allah, do you wish that I should kill him? He said: Yes. He said: Permit me to talk (to him in the way I deem fit). He said: Talk (as you like).

A variety of punishments, including death, have been instituted in Islamic jurisprudence that draw their sources from hadith literature.[6][18] Sources in hadith literature allege that Muhammad ordered the execution of Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf.[23] After the Battle of Badr, Ka'b had incited the Quraysh against Muhammad, and also urged them to seek vengeance against Muslims. Another person executed was Abu Rafi', who had actively propagandized against Muslims immediately before the Battle of Ahzab. Both of these men were guilty of insulting Muhammad, and both were guilty of inciting violence. While some[who?] have explained that these two men were executed for blaspheming against Muhammad, an alternative explanation[according to whom?] is that they were executed for treason and causing disorder (fasad) in society.[6]

Muhammad declared that there shall be no punishment for murdering anyone who disparages, abuses or insults him (tashtimu, sabb al rasool).[6] One hadith[24][6] tells of a man who killed his pregnant slave because she persisted in insulting Muhammad. Upon hearing this, Muhammad is reported to have exclaimed: "Do you not bear witness that her blood is futile!" (anna damah hadarun) This expression can be read as meaning that the killing was unnecessary, implying that Muhammad condemned it.[6] However, most hadith specialists interpreted it as voiding the obligation of paying the blood money which would normally be due to the woman's next of kin.[6] Another hadith reports Muhammad using an expression which clearly indicates the latter meaning:[6]

Narrated Ali ibn AbuTalib: A Jewess used to abuse the Prophet and disparage him. A man strangled her till she died. The Apostle of Allah declared that no recompense was payable for her blood.

Islamic law

[edit]Traditional jurisprudence

[edit]The Quran curses those who commit blasphemy and promises blasphemers humiliation in the Afterlife.[5] However, whether any Quranic verses prescribe worldly punishments is debated: some Muslims believe that no worldly punishment is prescribed while others disagree.[6] Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) of Sunni and Shia madhabs have declared different punishments for the religious crime of blasphemy, and they vary between schools. These are as follows:[18][2][25]

- Hanafi – views blasphemy as synonymous with apostasy, and therefore, accepts the repentance of apostates. Those who refuse to repent, their punishment is death if the blasphemer is a Muslim man, and if the blasphemer is a woman, she must be imprisoned with coercion (beating) till she repents and returns to Islam.[26] Imam Abu Hanifa opined that a non-Muslim can not be killed for committing blasphemy.[27] Other sources[who?] say his punishment must be a tazir (discretionary, can be arrest, caning, etc.).[28][29][failed verification]

- Maliki – view blasphemy as an offense distinct from, and more severe than apostasy. Death is mandatory in cases of blasphemy for Muslim men, and repentance is not accepted. For women, death is not the punishment suggested, but she is arrested and punished till she repents and returns to Islam or dies in custody.[30][31] A non-Muslim who commits blasphemy against Islam must be punished; however, the blasphemer can escape punishment by converting and becoming a devout Muslim.[32]

- Hanbali – view blasphemy as an offense distinct from, and more severe than apostasy. Death is mandatory in cases of blasphemy, for both Muslim men and women.[33][34]

- Shafi'i – recognizes blasphemy as a separate offense from apostasy, but accepts the repentance of blasphemers. If the blasphemer does not repent, the punishment is death.[2][35]

- Zahiri – views insulting God or Islamic prophets as apostasy.[36]

- Ja'fari (Shia) – views blasphemy against Islam, the Prophet, or any of the Imams, to be punishable with death, if the blasphemer is a Muslim.[37] In case the blasphemer is a non-Muslim, he is given a chance to convert to Islam, or else killed.[38]

Some jurists suggest that the sunnah in Sahih al-Bukhari, 3:45:687 and Sahih al-Bukhari, 5:59:369 provide a basis for a death sentence for the crime of blasphemy, even if someone claims not to be an apostate, but has committed the crime of blasphemy.[39] Some modern Muslim scholars contest that Islam supports blasphemy law, stating that Muslim jurists made the offense part of Sharia.[39][40]

The words of Ibn Abbas, a prominent jurist and companion of Muhammad, are frequently cited to justify the death penalty as punishment blasphemy:[6]

Any Muslim who blasphemes against Allah or His Messenger or blasphemes against any one from amongst the Prophets is thereby guilty of rejecting the truth of the Messenger of God, may Allah bless him and grant him peace. This is apostasy (ridda) for which repentance is necessary; if he repents he is released; if not then he is killed. Likewise, if any other person [non-Muslim] who is protected under a covenant becomes hostile and blasphemes against Allah or any one of Allah's Prophet and openly professes this, he breaches his covenant, so kill him.

— Ibn Qayyim al Jawziya and Ata 1998, 4:379

In Islamic jurisprudence, Kitab al Hudud and Taz'ir cover punishment for blasphemous acts.[41][42]

Blasphemy as apostasy

[edit]

Because blasphemy in Islam included rejection of fundamental doctrines,[3] blasphemy has historically been seen as an evidence of rejection of Islam, that is, the religious crime of apostasy. Some jurists believe that blasphemy by a Muslim who automatically implies the Muslim has left the fold of Islam.[7] A Muslim may find himself accused of being a blasphemer, and thus an apostate on the basis of the same action or utterance.[43][44] Not all blasphemy is apostasy, of course, as a non-Muslim who blasphemes against Islam has not committed apostasy. Blasphemy is defined as the act of speaking disrespectfully or irreverently about God and there is every other thing you can do to Cause blasphemy A specific example of blasphemy against the Holy Spirit occurs when someone attributes the good works of God (such as miracles) to Satan.

Modern state laws

[edit]

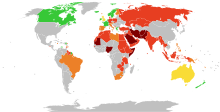

The punishments for different instances of blasphemy in Islam vary by jurisdiction,[8][45][46] but may be very severe. A convicted blasphemer may, among other penalties, lose all legal rights. The loss of rights may cause a blasphemer's marriage to be dissolved, religious acts to be rendered worthless, and claims to property—including any inheritance—to be rendered void. Repentance, in some Fiqhs, may restore lost rights except for marital rights; lost marital rights are regained only by remarriage. Women have blasphemed and repented to end a marriage. Muslim women may be permitted to repent, and may receive a lesser punishment than would befall a Muslim man who committed the same offense.[44] Most Muslim-majority countries have some form of blasphemy law and some of them have been compared to blasphemy laws in European countries (Britain, Germany, Finland etc.).[47] However, in five countries, including Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia, blasphemy is punishable by execution.[48] In Pakistan, more than a thousand people have been convicted of blasphemy since the 1980s; though none have been executed.[47]

History

[edit]Early and medieval Islam

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2022) |

According to Islamic sources Nadr ibn al-Harith, who was an Arab Pagan doctor from Taif, used to tell stories of Rustam and Isfandiyar to the Arabs and scoffed Muhammad.[49][50] After the battle of Badr, al-Harith was captured and, in retaliation, Muhammad ordered his execution in hands of Ali.[51][52][53]

According to certain hadiths, after Mecca's fall Muhammad ordered a number of enemies executed. Based on this early jurists postulated that sabb al-Nabi (abuse of the Prophet) was a crime "so heinous that repentance was disallowed and summary execution was required".[54]

Sadakat Kadri writes that the actual prosecutions for blasphemy in the Muslim historical record "are vanishingly infrequent". One of the "few known cases" was that of a Christian accused of insulting the Islamic Prophet Muhammad. It ended in an acquittal in 1293, though it was followed by a protest against a decision led by the famed and strict jurist Ibn Taymiyya.[55]

In the 20th and 21st century

[edit]

In recent decades Islamic revivalists have called for its enforcement on the grounds that criminalizing hostility toward Islam will safeguard communal cohesion.[54] In one country where strict laws on blaspheme were introduced in the 1980s, Pakistan, over 1300 people have been accused of blasphemy from 1987 to 2014, (mostly non-Muslim religious minorities), mostly for allegedly desecrating the Quran.[56] Over 50 people accused of blasphemy have been murdered before their respective trials were over,[57][58] and prominent figures who opposed blasphemy laws (Salman Taseer, the former governor of Punjab, and Shahbaz Bhatti, the Federal Minister for Minorities) have been assassinated.[56]

As of 2011, all Islamic majority nations, worldwide, had criminal laws on blasphemy. Over 125 non-Muslim nations worldwide did not have any laws relating to blasphemy.[59][60] In Islamic nations, thousands of individuals have been arrested and punished for blasphemy of Islam.[61][62] Moreover, several Islamic nations have argued in the United Nations that blasphemy against Muhammad is unacceptable, and that laws should be passed worldwide to proscribe it. In September 2012, the Organisation of Islamic Conference (OIC), who has sought for a universal blasphemy law over a decade, revived these attempts. Separately, the Human Rights Commission of the OIC called for "an international code of conduct for media and social media to disallow the dissemination of incitement material". Non-Muslim nations that do not have blasphemy laws, have pointed to abuses of blasphemy laws in Islamic nations, and have disagreed.[63][64][65]

Notwithstanding, controversies raised in the non-Muslim world, especially over depictions of Muhammad, questioning issues relating to the religious offense to minorities in secular countries. A key case was the 1989 fatwa against English author Salman Rushdie for his 1988 book entitled The Satanic Verses, the title of which refers to an account that Muhammad, in the course of revealing the Quran, received a revelation from Satan and incorporated it therein until made by Allah to retract it. Several translators of his book into foreign languages have been murdered.[66] In the UK, many supporters of Salman Rushdie and his publishers advocated unrestricted freedom of expression and the abolition of the British blasphemy laws. As a response, Richard Webster wrote A Brief History of Blasphemy in which he discussed freedom to publish books that may cause distress to minorities.[67]

Notable modern cases involving individuals

[edit]Assassination of Farag Foda

[edit]

Farag Foda (also Faraj Fawda; 1946 – 9 June 1992), was a prominent Egyptian professor, writer, columnist,[68] and human rights activist.[69] He was assassinated on 9 June 1992 by members of Islamist group al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya after being accused of blasphemy by a committee of clerics (ulama) at Al-Azhar University.[68] In December 1992, his collected works were banned.[70] In a statement claimed responsibility for the killing, Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya accused Foda of being an apostate from Islam, advocating the separation of religion from the state, and favouring the existing legal system in Egypt rather than the application of Sharia (Islamic law).[68] The group explicitly referred to the Al-Azhar fatwā when claiming responsibility.[71]

Imprisonment of Arifur Rahman

[edit]In September 2007, Bangladeshi cartoonist Arifur Rahman depicted in the daily Prothom Alo a boy holding a cat conversing with an elderly man. The man asks the boy his name, and he replies "Babu". The older man chides him for not mentioning the name of Muhammad before his name. He then points to the cat and asks the boy what it is called, and the boy replies "Muhammad the cat". Bangladesh does not have a blasphemy law but groups said the cartoon ridiculed Muhammad, torched copies of the paper and demanded that Rahman be executed for blasphemy. As a result, Bangladeshi police detained Rahman and confiscated copies of Prothom Alo in which the cartoon appeared.

Sudanese teddy bear blasphemy case

[edit]In November 2007, British schoolteacher Gillian Gibbons, who taught middle-class Muslim and Christian children in Sudan,[72] was convicted of insulting Islam by allowing her class of six-year-olds to name a teddy bear "Muhammad". On 30 November, thousands of protesters took to the streets in Khartoum,[73] demanding Gibbons's execution after imams denounced her during Friday prayers. Many Muslim organizations in other countries publicly condemned the Sudanese over their reactions[74] as Gibbons did not set out to cause offence.[75] She was released into the care of the British embassy in Khartoum and left Sudan after two British Muslim members of the House of Lords met President Omar al-Bashir.[76][77]

Asia Bibi blasphemy case

[edit]The Asia Bibi blasphemy case involved a Pakistani Christian woman, Aasiya Noreen (born c. 1971;[78] better known as Asia Bibi[79] convicted of blasphemy by a Pakistani court, receiving a sentence of death by hanging in 2010. In June 2009, Noreen was involved in an argument with a group of Muslim women with whom she had been harvesting berries after the other women grew angry with her for drinking the same water as them. She was subsequently accused of insulting the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, a charge she denied, and was arrested and imprisoned. In November 2010, a Sheikhupura judge sentenced her to death. If executed, Noreen would have been the first woman in Pakistan to be lawfully killed for blasphemy.[80][81]

The verdict, which was reached in a district court and needed to be upheld by a superior court, received worldwide attention. Various petitions, including one that received 400,000 signatures, were organized to protest Noreen's imprisonment, and Pope Benedict XVI publicly called for the charges against her to be dismissed. She received less sympathy from her neighbors and Islamic religious leaders in the country, some of whom adamantly called for her to be executed. Christian minorities minister Shahbaz Bhatti and Muslim politician Salmaan Taseer were both assassinated for advocating on her behalf and opposing the blasphemy laws.[82] Noreen's family went into hiding after receiving death threats, some of which threatened to kill Asia if released from prison.[83] Governor Salmaan Taseer and Pakistan's Minority Affairs Minister Shahbaz Bhatti both publicly supported Noreen, with the latter saying, "I will go to every knock for justice on her behalf and I will take all steps for her protection."[83] She also received support from Pakistani political scientist Rasul Baksh Rais and local priest Samson Dilawar.[84] The imprisonment of Noreen left Christians and other minorities in Pakistan feeling vulnerable, and liberal Muslims were also unnerved by her sentencing.[85]

Minority Affairs Minister Shahbaz Bhatti said that he was first threatened with death in June 2010 when he was told that he would be beheaded if he attempted to change the blasphemy laws. In response, he told reporters that he was "committed to the principle of justice for the people of Pakistan" and willing to die fighting for Noreen's release.[83] On 2 March 2011, Bhatti was shot dead by gunmen who ambushed his car near his residence in Islamabad, presumably because of his position on the blasphemy laws. He had been the only Christian member of Pakistan's cabinet.[86]

In January 2011, talking about the Asia Bibi blasphemy case, Pakistani politician Salmaan Taseer expressed views opposing the country's blasphemy law and supporting Asia Bibi. He was then killed by one of his bodyguards, Malik Mumtaz Qadri. After the murder, hundreds of clerics voiced support for the crime and urged a general boycott of Taseer's funeral.[87] The Pakistani government declared three days of national mourning and thousands of people attended his funeral.[88][89] Supporters of Mumtaz Qadri blocked police attempting to bring him to the courts and some showered him with rose petals.[90] In October, Qadri was sentenced to death for murdering Taseer. Some expressed concerns that the assassinations of Taseer and Bhatti may dissuade other Pakistani politicians from speaking out against the blasphemy laws.

Imprisonment of Fatima Naoot

[edit]In 2014, an Egyptian state prosecutor pressed charges against a former candidate for parliament, writer and poet Fatima Naoot, of blaspheming Islam when she posted a Facebook message which criticized the slaughter of animals during Eid al-Adha, a major Islamic festival.[91] Naoot was sentenced on 26 January 2016 to three years in prison for "contempt of religion." The prison sentence was effective immediately.[92]

Murder of Farkhunda Malikzada

[edit]Farkhunda Malikzada was a 27-year-old Afghan woman who was publicly beaten and slain by a mob of hundreds of people in Kabul on 19 March 2015.[93][94] Farkhunda had previously been arguing with a mullah named Zainuddin, in front of a mosque where she worked as a religious teacher,[95] about his practice of selling charms at the Shah-Do Shamshira Mosque, the Shrine of the King of Two Swords,[96] a religious shrine in Kabul.[97] During this argument, Zainuddin reportedly falsely accused her of burning the Quran. Police investigations revealed that she had not burned anything.[95] A number of prominent public officials turned to Facebook immediately after the death to endorse the murder.[98] After it was revealed that she did not burn the Quran, the public reaction in Afghanistan turned to shock and anger.[99][100] Her murder led to 49 arrests;[101] three adult men received twenty-year prison sentences, eight other adult males received sixteen year sentences, a minor received a ten-year sentence, and eleven police officers received one-year prison terms for failing to protect Farkhunda.[102] Her murder and the subsequent protests served to draw attention to women's rights in Afghanistan.[103]

Death sentence for Ahmad Al Shamri's atheism

[edit]Ahmad Al Shamri from the town of Hafar al-Batin, Saudi Arabia, was arrested on charges of atheism and blasphemy after allegedly use social media to state that he renounced Islam and the Prophet Mohammed, he was sentenced to death in February 2015.[104]

Death of Mashal Khan

[edit]Mashal Khan was a Pakistani student at the Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan who was killed by an angry mob in the premises of the university in April 2017 over allegations of posting blasphemous content online.[105][106]

Imprisonment of the governor of Jakarta

[edit]In 2017 in Indonesia, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama during his tenure as the governor of Jakarta, made a controversial speech while introducing a government project at Thousand Islands in which he referenced a verse from the Quran. His opponents criticized this speech as blasphemous, and reported him to the police. He was later convicted of blasphemy against Islam by the North Jakarta District Court and sentenced to two years imprisonment.[107][108][109][110] This decision barred him from serving as the governor of Jakarta, and he was replaced by his deputy, Djarot Saiful Hidayat.

Notable international controversies

[edit]Protests against depicting Muhammad

[edit]

In December 1999, the German news magazine Der Spiegel printed on the same page pictures of "moral apostles" Muhammad, Jesus, Confucius, and Immanuel Kant. Few weeks later, the magazine received protests, petitions and threats against publishing depictions of Muhammad. The Turkish TV-station Show TV broadcast the telephone number of an editor who then received daily calls.[111] A picture of Muhammad had been published by the magazine once before in 1998 in a special edition on Islam, without evoking similar protests.[112]

In 2008, several Muslims protested against the inclusion of Muhammad's depictions in the English Wikipedia's Muhammad article.[113][114] An online petition opposed a reproduction of a 17th-century Ottoman copy of a 14th-century Ilkhanate manuscript image depicting Muhammad as he prohibited Nasīʾ.[115] Jeremy Henzell-Thomas of The American Muslim deplored the petition as one of "these mechanical knee-jerk reactions [which] are gifts to those who seek every opportunity to decry Islam and ridicule Muslims and can only exacerbate a situation in which Muslims and the Western media seem to be locked in an ever-descending spiral of ignorance and mutual loathing."[116]

The Muhammad cartoons crisis

[edit]| Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy |

|---|

In September 2005, in the tense aftermath of the assassination of Dutch film director Theo van Gogh, killed for his views on Islam, Danish news service Ritzau published an article discussing the difficulty encountered by the writer Kåre Bluitgen to find an illustrator to work on his children's book The Qur'an and the life of the Prophet Muhammad (Danish:Koranen og profeten Muhammeds liv).[117][118] He said that three artists declined his proposal, which was interpreted as evidence of self-censorship out of fear of reprisals, which led to much debate in Denmark.[119][120] Reviewing the experiment, Danish scholar Peter Hervik wrote that it disproved the idea that self-censorship was a serious problem in Denmark, because the overwhelming majority of cartoonists had either responded positively or refused for contractual or philosophical reasons.[121] Furthermore, the Danish newspaper Politiken stated that they asked Bluitgen to put them in touch with the artists who reportedly declined his proposal, so his claim that none of them dared to work with him could be proved, but that Bluitgen refused, making his initial claim impossible to confirm.[122]

Flemming Rose, an editor at the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, invited professional illustrators to depict Muhammad as an experiment to see how much they felt threatened. The newspaper announced that this was an attempt to contribute to the debate about criticism of Islam and self-censorship. On 30 September 2005, the Jyllands-Posten published 12 editorial cartoons, most of which depicted the Prophet Muhammad. One cartoon by Kurt Westergaard depicted Muhammad with a bomb in his turban, which resulted in the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy (or Muhammad cartoons crisis) (Danish: Muhammedkrisen)[123] i.e. complains by Muslim groups in Denmark, the withdrawal of the ambassadors of Libya, Saudi Arabia and Syria from Denmark, protests around the world including violent demonstrations and riots in some Muslim countries as well as consumer boycotts of Danish products.[124] Carsten Juste, editor-in-chief at the Jyllands-Posten, claimed the international furor over the cartoons amounted to a victory for opponents of free expression. "Those who have won are dictatorships in the Middle East, in Saudi Arabia, where they cut criminals' hands and give women no rights," Juste told The Associated Press. "The dark dictatorships have won."[125] Commenting the cartoon that initiated the diplomatic crisis, American scholar John Woods expressed worries about Westergaard-like association of the Prophet with terrorism, that was beyond satire and offensive to a vast majority of Muslims.[126] Hervik also deplored that the newspaper's "desire to provoke and insult Danish Muslims exceeded the wish to test the self-censorship of Danish cartoonists."[121]

In Sweden, an online caricature competition was announced in support of Jyllands-Posten, but foreign minister Laila Freivalds pressured the provider to shut the page down (in 2006, her involvement was revealed to the public and she had to resign).[127]

In France, satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo republished the Jyllands-Posten cartoons of Muhammad. It was taken to court by Islamic organisations under French hate speech laws; it was ultimately acquitted of charges that it incited hatred.[128][129]

In July 2007, art galleries in Sweden declined to show drawings of artist Lars Vilks depicting Muhammad as a roundabout dog. While Swedish newspapers had published them already, the drawings gained international attention after the newspaper Nerikes Allehanda published one of them on 18 August to illustrate an editorial on the "right to ridicule a religion".[130] This particular publication led to official condemnations from Iran,[131] Pakistan,[132] Afghanistan,[133] Egypt[134] and Jordan,[135] and by the inter-governmental Organisation of the Islamic Conference.[136]

In 2006, the American comedy program South Park, which had previously depicted Muhammad as a superhero ("Super Best Friends)"[137] and has depicted Muhammad in the opening sequence since then,[138] attempted to satirize the Danish newspaper incident. They intended to show Muhammad handing a salmon helmet to Family Guy character Peter Griffin ("Cartoon Wars Part II"). However, Comedy Central who airs the series rejected the scene and its creators reacted by satirizing double standard for broadcast acceptability.

In April 2010, animators Trey Parker and Matt Stone planned to make episodes satirizing controversies over previous episodes, including Comedy Central's refusal to show images of Muhammad following the 2005 Danish controversy. After they faced Internet death threats, Comedy Central modified their version of the episode, obscuring all images and bleeping all references to Muhammad. In reaction, cartoonist Molly Norris created the Everybody Draw Mohammed Day, claiming that if many people draw pictures of Muhammad, threats to murder them all would become unrealistic. [139]

On 2 November 2011, Charlie Hebdo was firebombed right before its 3 November issue was due; the issue was called Charia Hebdo and satirically featured Muhammad as guest-editor.[140][141] The editor, Stéphane Charbonnier, known as Charb, and two co-workers at Charlie Hebdo subsequently received police protection.[142] In September 2012, the newspaper published a series of satirical cartoons of Muhammad, some of which feature nude caricatures of him. In January 2013, Charlie Hebdo announced that they would make a comic book on the life of Muhammad.[143]

In March 2013, Al-Qaeda's branch in Yemen, commonly known as Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), released a hit list in an edition of their English-language magazine Inspire. The list included Kurt Westergaard, Lars Vilks, Carsten Juste, Flemming Rose, Charb and Molly Norris, and others whom AQAP accused of insulting Islam.[144][145][146][147][148][149] On 7 January 2015, two masked gunmen opened fire on Charlie Hebdo's staff and police officers as vengeance for its continued caricatures of Muhammad,[150] killing 12 people, including Charb, and wounding 11 others.[151][152] Jyllands-Posten did not re-print the Charlie Hebdo cartoons in the wake of the attack, with the new editor-in-chief citing security concerns.[153]

Kamlesh Tiwari case

[edit]In October 2019, Kamlesh Tiwari, an Indian politician, was killed in a planned attack in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, for his views on Muhammad.[154][155][156]

On 2 December 2015, Azam Khan, a politician of the Samajwadi Party, stated that Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh members are homosexuals and that is why they do not get married.[157][158][159] The next day, Kamlesh Tiwari retaliated to Azam Khan's statement and called Muhammad as the first homosexual in the world.[157][160] Thousands of Muslims protested in Muzaffarnagar and demanded the death penalty for Tiwari,[157][161][162] with some demanding that he be "beheaded" for "insulting" Muhammad.[160] Tiwari was arrested in Lucknow on 3 December 2015 by Uttar Pradesh Police.[163][160] He was detained under National Security Act by the Samajwadi Party-led state government in Uttar Pradesh.[164] Tiwari spent several months in jail for his comment. He was charged under Indian Penal Code sections 153-A (promoting enmity between groups on the grounds of religion and doing acts prejudicial to maintenance of harmony) and 295-A (deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs).[165][166] Protest rallies against his statement were held by several Islamic groups in other parts of India, most of them demanding the death penalty.[167]

The protests demanding capital punishment for Tiwari triggered counter-protests by Hindu groups who accused Muslim groups of demanding enforcement of Islamic law of blasphemy in India.[160] His detention under National Security Act was revoked by Allahabad High Court in 2016.[168]

On 18 October 2019, Tiwari was murdered by two Muslim assailants, Farid-ud-din Shaikh and Ashfak Shaikh, in his office-cum-residence at Lucknow. The assailants came dressed in saffron kurtas to give him a sweets box with an address of a sweet shop in Surat city in Gujarat.[169][170] According to police officials, the assailants kept a revolver and knife inside the sweets box. During the attack, one assailant slit his throat while another fired at him.[170] Tiwari's aide Saurashtrajeet Singh was sent to bring cigarettes for them and when he returned he found Tiwari lying with his throat slit and his body ruptured with wounds.[170] He was declared dead during treatment at a hospital's trauma centre.[171] The post-mortem report revealed that he was stabbed 15 times on the upper part of body from jaws to chest, two deep cut marks on the neck points to attempt to slit his throat and shot once.[172]

Innocence of Muslims

[edit]Innocence of Muslims[173][174] is an anti-Islamic short film that was written and produced by Nakoula Basseley Nakoula.[175][176] Two versions of the 14-minute video were uploaded to YouTube in July 2012, under the titles The Real Life of Muhammad and Muhammad Movie Trailer.[177] Videos dubbed in Arabic were uploaded during early September 2012.[178] Anti-Islamic content had been added in post-production by dubbing, without the actors' knowledge.[179]

What was perceived as denigrating of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad resulted in demonstrations and violent protests against the video to break out on 11 September in Egypt and spread to other Arab and Muslim nations and to some western countries. The protests have led to hundreds of injuries and over 50 deaths.[180][181][182] Fatwas calling for the harm of the video's participants have been issued and Pakistani government minister Bashir Ahmad Bilour offered a bounty for the killing of Nakoula, the producer.[183][184][185] The film has sparked debates about freedom of speech and Internet censorship.[186]

Blasphemy in Sweden during Turkish-Sweden tensions

[edit]The incident happened amid rising diplomatic tension between the two countries and Turkey's objections to Sweden joining NATO. Turkey had earlier canceled a visit by Sweden's defense minister and is seeking political concessions, including the deportation of critics and Kurds. The act was described by Sweden's Foreign Minister as "appalling" and does not imply government support for the opinion expressed.[187]

Examples

[edit]

A variety of actions, speeches or behavior can constitute blasphemy in Islam. Some examples include insulting or cursing Allah, or Muhammad; mockery or disagreeable behavior towards beliefs and customs common in Islam; criticism of Islam's holy personages. Apostasy, that is, the act of abandoning Islam, or finding faults or expressing doubts about Allah (ta'til) and Qur'an, rejection of Muhammed or any of his teachings, or leaving the Muslim community to become an atheist is a form of blasphemy. Questioning religious opinions (fatwa) and normative Islamic views can also be construed as blasphemous. Improper dress, drawing offensive cartoons, tearing or burning holy literature of Islam, creating or using music or painting or video or novels to mock or criticize Muhammad are some examples of blasphemous acts.[189][190][191][192] In the context of those who are non-Muslims, the concept of blasphemy includes all aspects of infidelity (kufr).

Individuals have been accused of blasphemy or of insulting Islam for a variety of actions and words.

Blasphemy against holy personages

[edit]- speaking ill of Allah.[193]

- finding fault with Muhammad.[194][195][196][197][198]

- slighting a Prophet who is mentioned in the Qur'an,[199] or slighting a member of Muhammad's family.[200][201][202][203][204][205][206][207][208]

- claiming to be a Prophet or a messenger.[209][210]

- Visual depictions of Muhammad[196][211][212][213][214] or any other Prophet,[215] or films about Muhammad or other Prophets (Egypt).[216][217]

- writing Muhammad's name on the walls of a toilet (Pakistan).[218]

- naming a teddy bear Muhammad (Sudan). See Sudanese teddy bear blasphemy case.[219][220][221]

- invoking God while committing a forbidden act.[44]

Blasphemy against beliefs and customs

[edit]- finding fault with Islam.[222][223][224]

- saying Islam is an Arab religion; prayers five times a day are unnecessary; and the Qur'an is full of lies (Indonesia).[225]

- believing in transmigration of the soul or reincarnation or disbelieving in the afterlife (Indonesia).[226]

- expressing an atheist or a secular point of view[227][203][228][229][230][231] or publishing or distributing such a point of view.[66][203][232][233][234][235][236][237][238][239][240][241]

- using words that Muslims use because the individuals were not Muslims (Malaysia).[208][242]

- praying that Muslims become something else (Indonesia).[243]

- finding amusement in Islamic customs (Bangladesh).[244][245][246][247]

- publishing an unofficial translation of the Qur'an (Afghanistan).[248]

- practicing yoga (Malaysia).[249][250][251][252]

- insulting religious scholarship.[44]

- wearing the clothing of Jews or of Zoroastrians.[44]

- claiming that forbidden acts are not forbidden.[44]

- uttering "words of infidelity" (sayings that are forbidden).[44]

- participating in non-Islamic religious festivals.[44]

Blasphemy against mosques

[edit]See also

[edit]- Islam

- Apostasy in Islam

- Blasphemy law

- Blasphemy law in Afghanistan

- Blasphemy law in Algeria

- Blasphemy law in Bangladesh

- Blasphemy law in Egypt

- Blasphemy law in Indonesia

- Blasphemy law in Iran

- Blasphemy law in Jordan

- Blasphemy law in Malaysia

- Blasphemy in Pakistan

- Blasphemy law in Saudi Arabia

- Blasphemy law in the United Arab Emirates

- Blasphemy law in Yemen

- Islamic extremism

- Mansur Al-Hallaj

- Utaybah bin Abu Lahab

- Secular topics

References

[edit]- ^ Avery, Kenneth (2004). Psychology of Early Sufi Sama: Listening and Altered States. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-0415311069.

- ^ a b c d Wiederhold, Lutz (1 January 1997). "Blasphemy against the Prophet Muhammad and his companions (sabb al-rasul, sabb al-sahabah): The introduction of the topic into shafi'i legal literature and its relevance for legal practice under Mamluk rule". Journal of Semitic Studies. 42 (1): 39–70. doi:10.1093/jss/XLII.1.39. Archived from the original on 30 September 2024. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d McAuliffe, Jane (2020). "What does the Quran say about Blasphemy?". The Qur'an: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-086770-6. Archived from the original on 30 September 2024. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ Lorenz Langer (2014) Religious Offence and Human Rights: The Implications of Defamation of Religions Cambridge University PressISBN 978-1107039575 p. 332

- ^ a b Siraj Khan. "Blasphemy against the Prophet" Archived 30 September 2024 at the Wayback Machine, in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture (editors: Coeli Fitzpatrick and Adam Hani Walker). ISBN 978-1610691772, pp. 59–61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Siraj Khan. "Blasphemy against the Prophet" Archived 30 September 2024 at the Wayback Machine, in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture (editors: Coeli Fitzpatrick and Adam Hani Walker). ISBN 978-1610691772, pp. 59–67.

- ^ a b c Saeed & Saeed 2004, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b Saeed & Saeed 2004, pp. 38–9.

- ^ "Apostasy in Islam: A Historical and Scriptural Analysis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ P Smith (2003). "Speak No Evil: Apostasy, Blasphemy and Heresy in Malaysian Syariah Law". UC Davis Journal Int'l Law & Policy. 10, pp. 357–73.

- N Swazo (2014). "The Case of Hamza Kashgari: Examining Apostasy, Heresy, and Blasphemy Under Sharia". The Review of Faith & International Affairs 12(4). pp. 16–26.

- ^ Esposito, John (2018). "Freedom and Human Rights". Shariah: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press. p. 158.

- ^ a b Juan Eduardo Campo, ed. (2009). "Blasphemy". Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing.

- ^ See:

- Siraj Khan. "Blasphemy against the Prophet", in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture (ed: Coeli Fitzpatrick Ph.D., Adam Hani Walker). ISBN 978-1610691772, pp. 59–67.

- Hassner, R. E. (2011). "Blasphemy and Violence". International Studies Quarterly 55(1). pp. 23–24;

- Lewis, Bernard. "Behind the Rushdie affair." The American Scholar 60.2 (1991), pp. 185–96;

- Stanfield-Johnson, R. (2004). "The tabarra'iyan and the early Safavids". Iranian Studies 37(1). pp. 47–71.

- ^ Talal Asad, in Hent de Vries (ed.). Religion: Beyond a Concept. Fordham University Press (2008). ISBN 978-0823227242. pp. 589–92

- ^ a b Burney Abbas, Shemeem. Pakistan's Blasphemy Laws: From Islamic Empires to the Taliban. University of Texas Press. pp. 39–40.

At times the Prophet's adversaries compared him to the poets of the desert as if he were a man possessed or mad and his Qur'anic revelations madness. His anguish emanated from the ridicule cast on him, aggravated by his unlettered status, the denying of his message of social justice and human rights, his wisdom, and his sensitivity...In these verses Muhammad received solace from God...Sometimes the comfort Muhammad received was about retribution in the hereafter...The Qur'anic evidence indicates that Muhammad was counseled to leave justice to the Almighty. He was never commanded to bring blasphemy punishments against his perpetrators; he was to seek only mercy and forgiveness for them.

- ^ [Quran 6:108]

- ^ According to Abbas "waging war against Allah and His messenger" must be interpreted as "those who disbelieve in Allah and His messenger", according to the two Jalals the verse is directed towards who "fights against Muslims", according to Kathir "waging war" "includes disbelief". See "Commentaries for 5:33". quranx.com. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Saeed, Abdullah; Hassan Saeed (2004). Freedom of Religion, Apostasy and Islam. Burlington VT: Ashgate Publishing Company. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-7546-3083-8.

- ^ Brian Winston (2014). The Rushdie Fatwa and After: A Lesson to the Circumspect, Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137388599. p. 74, Quote: "(In the case of blasphemy and Salman Rushdie) the death sentence it pronounced was grounded in a jurisprudential gloss on the Surah al-Ahzab (33:57)".

- ^ Richard T. Antoun (2014). Muslim Preacher in the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691602752. p. 194, Quote: "All the negative connotations of factionalism, social dissension, blasphemy, and their logical conclusions conspiracy, military confrontation and damnation – are captured in the title of this sura, al-Ahzab (The Confederates, Book 33)"

- ^ According to Akyol, this verse indicates that "Muslims are not supposed to be part of a discourse that mocks Islam, but all they have to do is stay away from it. Even then, the withdrawal should last only until the discourse changes into something inoffensive. Once mockery ends, dialogue can restart". See Akyol, Mustafa, Islam Without Extremes: A Muslim Case for Liberty, 2013 p. 285

- ^ Saeed & Saeed 2004, pp. 37–39.

- ^ a b Rubin, Uri. The Assassination of Kaʿb b. al-Ashraf. Oriens, Vol. 32. (1990), pp. 65–71.

- ^ Sunan Abu Dawood, 38:4348

- ^ Saeed, Abdullah. "Ambiguities of Apostasy and The Repression of Muslim Dissent." The Review of Faith & International Affairs 9.2 (2011): 31–38.

- ^ * Abu al-Layth al-Samarqandi (983), Mukhtalaf al-Riwayah, vol. 3, pp. 1298–99

- Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Tahawi (933), Mukhtasar Ikhtilaf al-Ulama, vol. 3, p. 504

- Ali ibn Hassan al-Sughdi (798); Kitab al-Kharaj; Quote: "أيما رجل مسلم سب رَسُوْل اللهِ صَلَّى اللهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ أو كذبه أو عابه أوتنقصه فقد كفر بالله وبانت منه زوجته ، فإن تاب وإلا قتل ، وكذلك المرأة ، إلا أن أبا حنيفة قَالَ: لا تقتل المرأة وتجبر عَلَى الإسلام"; Translation: "A Muslim man who blasphemes the Messenger of Allah, denies him, reproaches him, or diminishes him, he has committed apostasy in Allah, and his wife is separated from him. He must repent, or else is killed. And this is the same for the woman, except Abu Hanifa said: Do not kill the woman, but coerce her back to Islam".

- ^ Mazhar, Arafat (2 November 2015). "Blasphemy and the death penalty: Misconceptions explained". Dawn. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Tahawi (933), Mukhtasar Ikhtilaf al-Ulama, vol. 3, p. 504

- ^ P. Smith (2003), Speak No Evil: Apostasy, Blasphemy and Heresy in Malaysian Syariah Law, UC Davis Journal Int'l Law & Policy, 10, pp. 357–73;

- N. Swazo (2014), The Case of Hamza Kashgari: Examining Apostasy, Heresy, And Blasphemy Under Sharia, The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 12(4), pp. 16–26

- ^ Qadi 'Iyad ibn Musa al-Yahsubi (1145), Kitab Ash-shifa (كتاب الشفاء بتعريف حقوق المصطفى), pp. 373–441 (Translated in English by AA Bewley, OCLC 851141256, (Review Contents in Part 4 Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Read Excerpts from Part 4 Archived 9 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Accessed on: 10 January 2015)

- ^ D Jordan (2003), Dark Ages of Islam: Ijtihad, Apostasy, and Human Rights in Contemporary Islamic Jurisprudence, The. Wash. & Lee Race & Ethnic Anc. Law Journal, Vol. 9, pp. 55–74

- ^ Carl Ernst (2005), "Blasphemy: Islamic Concept", Encyclopedia of Religion (Editor: Lindsay Jones), Vol 2, Macmillan Reference, ISBN 0-02-865735-7

- ^ Abdullah Saeed and Hassan Saeed (2004), Freedom of Religion, Apostasy and Islam, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0754630838

- ^ * Ibn Taymiyyah (a Salafi, related to Hanbali school), al-Sārim al-Maslūl 'ala Shātim al-Rasūl (Translation: A ready sword against those who insult the Messenger), Published in 1297 AD in Arabic, Reprinted in 1975 and 2003 by Dar-ibn Hazm (Beirut)

- ^ P. Smith (2003), Speak No Evil: Apostasy, Blasphemy and Heresy in Malaysian Syariah Law, UC Davis Journal Int'l Law & Policy, 10, pp. 357–73;

- F. Griffel (2001), Toleration and exclusion: al-Shafi 'i and al-Ghazali on the treatment of apostates, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64(3), pp. 339–54

- ^ "Summary of Aqida - Verbal Nullifiers in the Chapter on Prophecies". dorar.net. Archived from the original on 30 September 2024. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Ayatullah Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei (1992), Minhaj al-Salihin, vol. 2, pp. 43–45;

- Ali ibn Ahmad al-Amili al-Thani (1602), Sharh al-Luma al-Dimashqiya, vol. 9, pp. 194–95;

- Muhammad ibn al-Hassan al-Tusi (1067), Al-Nihaya, pp. 730–31 and Tadhib al-Ahkam, vol. 10, p. 85;

- Ali ibn al-Hussein "Sharif al-Murtada" (1044). Al-Intisar, pp. 480–81;

- Ali ibn Babawaih al-Qummi al-Saduq (991), Al-Hidaya fi al-Usul wa al-Furu, pp. 295–97

- ^ Ali ibn al-Hussein al-Murtada (1044), Al-Intisar, pp. 480–81

- ^ a b O'Sullivan, Declan (2001). "The Interpretation of Qur'anic Text to Promote or Negate the Death Penalty for Apostates and Blasphemers". Journal of Qur'anic Studies. 3 (2). Edinburgh University Press: 63–93. doi:10.3366/jqs.2001.3.2.63. JSTOR 25728038.

- ^ Islamic scholar attacks Pakistan's blasphemy laws Archived 30 September 2024 at the Wayback Machine Guardian 20 January 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2010

- ^ Peters, R. (2005). Crime and punishment in Islamic Law: Theory and practice from the Sixteenth to the Twenty-First Century (Vol. 2). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Schirrmacher, C. (2008). "Defection from Islam: A Disturbing Human Rights Dilemma" (PDF). islaminstitut.de. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2013.

- ^ Saeed & Saeed 2004, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Blasphemy: Islamic Concept". Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 2. Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale. 2005. pp. 974–76.

- ^ See Blasphemy law.

- ^ "Govt warned against amending blasphemy law". The News. 12 February 2010. Retrieved 16 February 2010. [dead link]

- ^ a b Gerhard Böwering; Patricia Crone; Mahan Mirza, eds. (2013). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0691134840. Archived from the original on 30 September 2024. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Fox, Jonathan (2015). Political Secularism, Religion, and the State: A Time Series Analysis of Worldwide Data. Cambridge University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9781316299685.

- ^ Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 2, Part 2, p. 179, Irfan Shahîd. Also see footnote

- ^ Husayn Haykal, Muhammad (2008). The Life of Muhammad. Selangor: Islamic Book Trust. p. 250. ISBN 978-983-9154-17-7.

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Vol. VII, 1993, p. 872

- ^ "Sirat Rasul Allah" by Ibn Ishaq, pp. 135–36

- ^ Abdul-Rahman, Muhammad Saed (2009). The Meaning and Explanation of the Glorious Qur'an. Vol. 3 (2 ed.). MSA Publication Limited. p. 412. ISBN 978-1-86179-769-8. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ a b Kadri, Sadakat (2012). Heaven on Earth: A Journey Through Shari'a Law from the Deserts of Ancient Arabia ... Macmillan. p. 252. ISBN 9780099523277. Archived from the original on 30 September 2024. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ Michel, Muslim Theologian's Response, pp. 69–71)

- ^ a b "What are Pakistan's blasphemy laws?". BBC News. 6 November 2014. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "Timeline: Accused under the Blasphemy Law". Dawn.com. 18 August 2013. Archived from the original on 12 May 2024. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Hashim, Asad (17 May 2014). "Living in fear under Pakistan's blasphemy law". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

In Pakistan, 17 people are on death row for blasphemy, and dozens more have been extrajudicially murdered.

- ^ "Laws Penalizing Blasphemy, Apostasy and Defamation of Religion are Widespread". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 21 November 2012. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013.

- ^ Rehman, Javaid. "The Shari 'ah, International Human Rights Law and The Right To Hold Opinions and Free Expression: After Bilour's Fatwa." Islam and International Law: Engaging Self-Centrism from a Plurality of Perspectives (2013): 244.

- ^ Forte, David F. "Apostasy and Blasphemy in Pakistan." Conn. J. Int'l L. 10 (1994): 27.

- ^ Silence. How Apostasy and Blasphemy Codes Are Choking Freedom Worldwide. By Paul Marshall and Nina Shea. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- ^ "Michael Totten, Radical Islam's global reaction: the push for blasphemy laws (January/February 2013)". Archived from the original on 6 January 2013.

- ^ "Islamic states to reopen quest for global blasphemy law". Reuters. 19 September 2012. Archived from the original on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ "Blasphemy Laws Exposed – The Consequences of Criminalizing Defamation of Religions" (PDF). humanrightsfirst.org. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ a b "Blasphemy Salman Rushdie". Constitutional Rights Foundation. 2009. Archived from the original on 18 August 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ^ Webster, Richard (1990). A Brief History of Blasphemy: Liberalism, Censorship and 'The Satanic Verses'. Southwold: The Orwell Press. ISBN 0951592203.

- ^ a b c "Document – Egypt: Human Rights Abuses By Armed Groups". amnesty.org. Amnesty International. September 1998. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ Miller, Judith (19 July 2011). God Has Ninety-Nine Names: Reporting from a Militant Middle East. Simon and Schuster. p. 26. ISBN 9781439129418. Archived from the original on 30 September 2024. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ de Baets, Antoon (2002). Censorship of Historical Thought: A World Guide, 1945–2000. Greenwood Publishing. p. 196. ISBN 9780313311932. Archived from the original on 30 September 2024. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

In December 1992 Foda's collected works were banned

- ^ de Waal, Alex (2004). Islamism and Its Enemies in the Horn of Africa. C. Hurst & Co. p. 60.

- ^ Day, Elizabeth (8 December 2007). "I was terrified that the guards would come in and teach me a lesson". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Stratton, Allegra (30 November 2007). "Jailed teddy row teacher appeals for tolerance". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- ^ "Muhammad & the teddy bear: a case of intercultural incompetence". 29 November 2007. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ^ "Sudanese Views differ in Teddy Row", News, UK: BBC, 2 December 2007, archived from the original on 23 January 2020, retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Teddy row teacher freed from jail Archived 3 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine, BBC World Service, 3 December 2007

- ^ "Teddy bear" teacher leaves Sudan after pardon Archived 13 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine", MSNBC

- ^ Kazim, Hasnain (19 November 2010). "Eine Ziege, ein Streit und ein Todesurteil" [A goat, a fight and a death sentence]. Der Spiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Fear for Pakistan's death row Christian woman". BBC News. 5 December 2010. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ^ Hussain, Waqar (11 November 2010). "Christian Woman Sentenced to Death". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Crilly, Rob; Sahi, Aoun (9 November 2010). "Christian Woman sentenced to Death in Pakistan for blasphemy". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ "Militants say killed Pakistani minister for blasphemy". Reuters. 2 March 2011. Archived from the original on 5 March 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ a b c Guerin, Orla (6 December 2010). "Pakistani Christian Asia Bibi 'has price on her head'". BBC. Archived from the original on 7 December 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ^ McCarthy, Julie (14 December 2010). "Christian's Death Verdict Spurs Holy Row in Pakistan". NPR. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "Salmaan Taseer came here and he sacrificed his life for me". The Independent. 8 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Anthony, Augustine (2 March 2011). "Militants say killed Pakistan minister for blasphemy". Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 March 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ R. Upadhyay, Barelvis and Deobandhis: "Birds of the Same Feather" Archived 4 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Eurasia Review, courtesy of the South Asia Analysis Group. 28 January 2011.

- ^ Sana Saleem, "Salmaan Taseer: murder in an extremist climate" Archived 18 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 5 January 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Aleem Maqbool and Orla Guerin, "Salman Taseer: Thousands mourn Pakistan governor" Archived 12 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine: "One small religious party, the Jamaat-e-Ahl-e-Sunnat Pakistan, warned that anyone who expressed grief over the assassination could suffer the same fate. 'No Muslim should attend the funeral or even try to pray for Salman Taseer or even express any kind of regret or sympathy over the incident,' the party said in a statement. It said anyone who expressed sympathy over the death of a blasphemer was also committing blasphemy." BBC News South Asia, 5 January 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "Demonstrators Prevent Court Appearance of Alleged Pakistani Assassin". Voice of America. 6 January 2011. Archived from the original on 9 January 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Days after Mauritania sentences man to death for 'insulting Islam', Egypt to try female writer for similar offence Archived 6 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine Agence France-Presse, MG Africa (28 December 2014)

- ^ "Egyptian writer Fatima Naoot sentenced to 3 years in jail for 'contempt of religion' – Politics – Egypt – Ahram Online". english.ahram.org.eg. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ "Family of Afghan woman lynched by mob demands justice". AlJazeera. 2 April 2015. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ The Killing of Farkhunda. New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ a b Rasmussen, Sune Engel (23 March 2015). "Farkhunda's family take comfort from tide of outrage in wake of her death". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 July 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Joseph Goldstein (29 March 2015). "Woman Killed in Kabul Transformed From Pariah to Martyr". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ "Afghan woman Farkhunda lynched in Kabul 'for speaking out'". BBC. 23 March 2015. Archived from the original on 7 September 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Shalizi, Hamid; Donati, Jessica (20 March 2015). "Afghan cleric and others defend lynching of woman in Kabul". Reuters. Reuters. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ^ Moore, Jack (23 March 2015). "Afghans Protest Brutal Mob Killing of 'Innocent' Woman". Newsweek. Newsweek. Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "What's the Future for Women's Rights in Afghanistan?". Equal Times. 14 April 2015. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ "Trial begins in case of Kabul lynching of Farkhunda". BBC News. 2 May 2015. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ "Afghan court quashes Farkhunda mob killing death sentences". BBC News. 2 July 2015. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "A Memorial To Farkhunda Appears In Kabul". Solidarity Party of Afghanistan. RFE/RL. 23 October 2015. Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ McKernan, Bethan (27 April 2017). "Man 'sentenced to death for atheism' in Saudi Arabia". The Independent. Beirut. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "Pakistan 'blasphemy killing': murdered student 'devoted to Islam'". euronews. 14 April 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ "Pakistan journalism student latest victim of blasphemy vigilantes". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ "Ahok Jailed for Two Years". metrotvnews.com. 9 May 2017. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ "Ahok Sent to 2 Years in Prison for Blasphemy". en.tempo.co. 9 May 2017. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ "Jakarta governor Ahok found guilty of blasphemy, jailed for two years". theguardian. 9 May 2017. Archived from the original on 26 June 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ "Jakarta governor Ahok found guilty of blasphemy". BBC. Archived from the original on 9 May 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ Terror am Telefon Archived 2 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Spiegel, 7 February 2000

- ^ Spiegel Special 1, 1998, p. 76

- ^ "Muslims Protest Wikipedia Images of Muhammad". Fox News. 6 February 2008. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- ^ Cohen, Noam (5 February 2008). "Wikipedia Islam Entry Is Criticized". New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- ^ MS Arabe 1489. The image used by Wikipedia is hosted on Wikimedia Commons (upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0d/Maome.jpg). The reproduction originates from the website of the Bibliothèque nationale de France [1] Archived 10 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wikipedia and Depictions of the Prophet Muhammad: The Latest Inane Distraction Archived 14 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 10 February 2008

- ^ Hansen, John; Hundevadt, Kim (2006). Provoen og Profeten: Muhammed Krisen bag kulisserne (in Danish). Copenhagen: Jyllands-Postens Forlag. ISBN 87-7692-092-5.

- ^ Bluitgen, Kåre (2006). Koranen og profeten Muhammeds liv (in Danish). Anonymous illustrator. Høst & Søn/Tøkk. p. 268. ISBN 978-87-638-0049-5. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015.

- ^ "Dyb angst for kritik af islam ("Profound anxiety about criticism of Islam")". Politiken (in Danish). 17 September 2005. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Rose, Flemming (19 February 2006). "Why I Published Those Cartoons". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ a b Hervik, Peter (2012). "The Danish Muhammad Cartoon Conflict" (PDF). Current Themes in IMER Research. 13. Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM). ISSN 1652-4616. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ Politiken 12. Februar 2006 "Muhammedsag: Ikke ligefrem en genistreg"

- ^ Henkel, Heiko (Fall 2010). "Fundamentally Danish? The Muhammad Cartoon Crisis as Transitional Drama" (PDF). Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-knowledge. 2. VIII. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ Jensen, Tim (2006). "The Muhammad Cartoon Crisis. The tip of an Iceberg", Japanese religion. pp. 5–7.

- ^ Vries, Lloyd (2 February 2006). "Cartoon Inflames Muslim World". CBS News. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ "Explaining the outrage". Chicago Tribune. 8 February 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2024. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ "Swedish foreign minister resigns over cartoons". Reuters AlertNet. Archived from the original on 22 March 2006. Retrieved 21 March 2006.

- ^ Leveque, Thierry (22 March 2007). "French court clears weekly in Mohammad cartoon row". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Leveque, Thierry (22 March 2007). "French court clears weekly in Mohammad cartoon row". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Ströman, Lars (18 August 2007). "Rätten att förlöjliga en religion" (in Swedish). Nerikes Allehanda. Archived from the original on 6 September 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

English translation: Ströman, Lars (28 August 2007). "The right to ridicule a religion". Nerikes Allehanda. Archived from the original on 30 August 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007. - ^ "Iran protests over Swedish Muhammad cartoon". Agence France-Presse. 27 August 2007. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- ^ "Pakistan Condemns the Publication of Offensive Sketch in Sweden" (Press release). Pakistan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 30 August 2007. Archived from the original on 4 September 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ Salahuddin, Sayed (1 September 2007). "Indignant Afghanistan slams Prophet Mohammad sketch". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 September 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- ^ Fouché, Gwladys (3 September 2007). "Egypt wades into Swedish cartoons row". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 September 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- ^ "Jordan condemns new Swedish Mohammed cartoon". Agence France-Presse. 3 September 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2007. [dead link]

- ^ "The Secretary General strongly condemned the publishing of blasphemous caricatures of Prophet Muhammad by Swedish artist" (Press release). Organisation of the Islamic Conference. 30 August 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- ^ "Super Best Friends". South Park. Season 5. Episode 68. 4 July 2001.

- ^ "Ryan j Budke. "South Park's been showing Muhammad all season!" TVSquad.com; April 15, 2006". Tvsquad.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "Texas shooting: What have we learned five years after 'Draw Muhammad Day'?". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ Simons, Stefan (20 September 2012). "'Charlie Hebdo' Editor in Chief: 'A Drawing Has Never Killed Anyone'". Spiegel Online. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ Anaëlle Grondin (7 January 2015) «Charlie Hebdo»: Charb, le directeur de la publication du journal satirique, a été assassiné Archived 24 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine (in French) 20 Minutes.

- ^ Trois «Charlie» sous protection policière Archived 19 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine (in French) Libération. 3 November 2011.

- ^ Taylor, Jerome (2 January 2013). "It's Charlie Hebdo's right to draw Muhammad, but they missed the opportunity to do something profound". The Independent. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ "Has al-Qaeda Struck Back? Part One". 8 January 2015. Archived from the original on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Bennet, Dashiell (1 March 2013). "Look Who's on Al Qaeda's Most-Wanted List". The Wire. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ Urquhart, Conal. "Paris Police Say 12 Dead After Shooting at Charlie Hebdo". Time. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

Witnesses said that the gunmen had called out the names of individual from the magazine. French media report that Charb, the Charlie Hebdo cartoonist who was on al Qaeda most wanted list in 2013, was seriously injured.

- ^ Ward, Victoria (7 January 2015). "Murdered Charlie Hebdo cartoonist was on al Qaeda wanted list". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ "French satirical paper Charlie Hebdo attacked in Paris". BBC News. 2 November 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ Cormack, Lucy (8 January 2015). "Charlie Hebdo editor Stephane Charbonnier crossed off chilling al-Qaeda hitlist". The Age. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ "Les deux hommes criaient "Allah akbar" en tirant". L'essentiel Online. 7 January 2015. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ Kim Willsher et al. (7 January 2015) Paris terror attack: huge manhunt under way after gunmen kill 12 Archived 7 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian

- ^ Willsher, Kim (7 January 2015). "Satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo attacked by gunmen". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ Sillesen, Lene Bech (8 January 2015). "Why a Danish newspaper won't publish the Charlie Hebdo cartoons". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ Chakraborty, Pathikrit (18 October 2019). "Kamlesh Tiwari: Hindu Mahasabha leader Kamlesh Tiwari stabbed to death in Lucknow". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ Lucknow: Hindu Samaj Party leader Kamlesh Tiwari killed, assailants slit his throat Archived 9 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, India Today (October 18, 2019)

- ^ Kamlesh Tiwari murder: UP Police says case solved, remarks on Prophet Muhammad behind killing Archived 16 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, India Today (October 19, 2019)

- ^ a b c "This is what Kamlesh Tiwari said about Prophet Muhammad which infuriated Muslims". Zee News. 12 December 2015. Archived from the original on 11 June 2024. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ "Azam Khan no stranger to controversies, has a history of squabbles". Hindustan Times. 27 July 2019. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Tiwari, Mrigank (1 December 2015). "RSS volunteers are 'homosexuals', says Azam Khan". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 16 June 2024. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d Who was Kamlesh Tiwari, the Hindu Samaj Party leader killed in broad daylight in Lucknow? Archived 6 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, India Today (October 18, 2019)

- ^ Rana, Uday (11 December 2015). "1 lakh Muslims gather in Muzaffarnagar, demand death for Kamlesh Tiwari". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 28 November 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ "Here's why 1 lakh Muslims are demanding the death penalty for Kamlesh Tiwari". DNA India. 12 December 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ Bhatia, Ishita (4 December 2015). "Kamlesh Tiwari not a member, says Hindu Mahasabha". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ Kamlesh Tiwari may contest U.P. bypolls Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Mohammad Ali, The Hindu (September 20, 2016), Quote: "Mr. Tiwari, who was granted bail last week by a Lucknow court, will remain in jail until the Allahabad High Court decides on his plea against the slapping of the National Security Act (NSA) on him by the State government."

- ^ Preeti (5 January 2016). "All You Need To Know About Malda Violence: Explained". OneIndia.com. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ "Hindu Mahasabha leader Kamlesh Tiwari found murdered inside house in Lucknow". The Indian Express. 18 October 2019. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ "Here's why 1 lakh Muslims are demanding the death penalty for Kamlesh Tiwari". DNA India. 12 December 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ "Kamlesh Tiwari Murder: Wife Blames 'Maulanas' for Hindu Leader's Death, Cops Call It 'Purely Criminal'". News18. 18 October 2019. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Plan to kill Kamlesh Tiwari hatched 2 months ago: Police Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, India Today (October 19, 2019)

- ^ a b c Shaikh, Sarfaraz (19 October 2019). "Kamlesh Tiwari murder case: Six detained in Surat". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Saffron fringe group leader Kamlesh Tiwari killed in Lucknow Archived 9 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, The Hindu (October 18, 2019)

- ^ Kamlesh Tiwari was stabbed 15 times, shot once | Post-mortem report Archived 13 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine, India Today (October 23, 2019)

- ^ "Anti-Muslim film got LA County permit for shoot". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. 20 September 2012. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

Anti-Muslim film had permit allowing 1-day shoot at LA County ranch, use of fire, animals

- ^ "County of Los Angeles Releases Redacted Film Permit for "Desert Warriors"" (PDF). FilmLA. 20 September 2012. f00043012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

Note: This document has been redacted due to concerns for safety and security of persons and locations

- ^ Esposito, Richard; Ross, Brian; Galli, Cindy (13 September 2012). "Anti-Islam Producer Wrote Script in Prison: Authorities, 'Innocence of Muslims' Linked to Violence in Egypt, Libya". abcnews.go.com. ABC News. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ Dion Nissenbaum; James Oberman; Erica Orden (13 September 2012). "Behind Video, a Web of Questions". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ Zahos, Zachary (19 September 2012). "The Art of Defamation". The Cornell Daily Sun. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ Lovett, Ian (15 September 2012). "Man Linked to Film in Protests Is Questioned". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ Murphy, Dan (12 September 2012). "There-may-be-no-anti-Islamic-movie-at-all". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ "Death, destruction in Pakistan amid protests tied to anti-Islam film". CNN. 21 September 2012. Archived from the original on 23 November 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ "Egypt newspaper fights cartoons with cartoons". CBS News. Associated Press. 26 September 2012. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ Latest Protests Against Depictions of Muhammad retrieved 1 October 2012 [dead link]

- ^ Fatwa issued by Muslim cleric against participants in an anti-Islamic film retrieved 1 October 2012 Archived 4 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Egypt cleric issues fatwa against 'Innocence of Muslims' cast Archived 11 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 1 October 2012

- ^ "Anti-Islam film: US condemns Pakistan minister's bounty". BBC News. 23 September 2012. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ Fenton, Thomas (12 September 2012). "Should Innocence of Muslims be censored?". Global Post. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ "Turkey condemns 'vile' Sweden Quran-burning protest". BBC News. 21 January 2023. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ "Salman Rushdie on Surviving the Fatwa". The New Yorker. 6 February 2023. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Lesson 13 : The Types of Blasphemy and Blasphemers". 20 October 2007. Archived from the original on 29 September 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ Lawton, D. (1993). Blasphemy. Univ of Pennsylvania Press

- ^ CW Ernst, in Eliade (Ed), Blasphemy – Islamic Concept, The encyclopedia of religion, New York (1987)

- ^ Marshall and Shea (2011), Silenced, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199812288

- ^ "Egypt bans 'blasphemous' magazine". BBC. 8 April 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ Ibrahim, Yusha'u A. (20 June 2009). "Nigeria: Blasphemy – Rioters Burn Police Outpost, Injure 12". Daily Trust. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ Ibrahim, Yusha'u A. (11 August 2008). "Nigeria: Mob Kills 50-Year-Old Man for 'Blasphemy'". Daily Trust. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ a b "Nigeria: International Religious Freedom Report 2008". U.S. Department of State. 2008. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ "Blasphemy Laws and Intellectual Freedom in Pakistan". South Asian Voice. August 2002. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2009.