Gospel of Mark

| Part of a series on |

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

The Gospel of Mark[a] is the second of the four canonical Gospels and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells of the ministry of Jesus from his baptism by John the Baptist to his death, the burial of his body, and the discovery of his empty tomb. It portrays Jesus as a teacher, an exorcist, a healer, and a miracle worker, though it does not mention a miraculous birth or divine pre-existence.[3] Jesus refers to himself as the Son of Man. He is called the Son of God but keeps his messianic nature secret; even his disciples fail to understand him.[4] All this is in keeping with the Christian interpretation of prophecy, which is believed to foretell the fate of the messiah as suffering servant.[5]

An early church tradition, deriving from Papias of Hierapolis (c.60–c.130 AD),[6] regards the Gospel as based on the preaching of Saint Peter, and written down by John Mark, who is named in the Acts of the Apostles as a companion of Saint Peter.[7][8][9] Most critical scholars reject this tradition, and it is generally agreed that it was written anonymously for a gentile audience, probably in Rome, sometime shortly before or after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD.[10][b]

Composition

[edit]

Authorship and date

[edit]An early Christian tradition deriving from Papias of Hierapolis (c.60–c.130 AD)[6] reagrds the Gospel as being based on the preaching of Saint Peter, as recorded by John Mark, who is mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles as a companion and interpreter of Peter.[7][8][9] Most scholars argue that it was written anonymously,[7][9][b] and that the name of Mark was attached to it to link it to an authoritative figure,[8] according to Adela Yarbro Collins already early on, and not in a later stage of the early Church history.[c] It is usually dated through the eschatological discourse in Mark 13, which scholars interpret as pointing to the First Jewish–Roman War (66–74 AD)—a war that led to the destruction of the Second Temple in AD 70. This would place the composition of Mark either immediately after the destruction or during the years immediately prior.[12][10][d] The dating around 70 AD is not dependent on the naturalistic argument that Jesus could not have made an accurate prophecy; scholars like Michael Barber and Amy-Jill Levine argue the Historical Jesus predicted the destruction of the Temple.[13] Whether the Gospels were composed before or after 70 AD, according to Bas van Os, the lifetime of various eyewitnesses that includes Jesus's own family through the end of the First Century is very likely statistically.[14] Markus Bockmuehl finds this structure of lifetime memory in various early Christian traditions.[15] The author used a variety of pre-existing sources, such as the conflict stories which appear in Mark 2:1-3:6, apocalyptic discourse such as Mark 13:1–37, miracle stories, parables, a passion narrative, and collections of sayings, although not the hypothesized Q source.[8][16] While Werner Kelber in his media contrast model argued that the transition from oral sources to the written Gospel of Mark represented a major break in transmission, going as far to claim that the latter tried to stifle the former, James DG Dunn argues that such distinctions are greatly exaggerated and that Mark largely preserved the Jesus tradition back to his lifetime.[17][18] Rafael Rodriguez too is critical of Kelber's divide.[19]

Setting

[edit]The Gospel of Mark was written in Greek, for a gentile audience, and probably in Rome, although Galilee, Antioch (third-largest city in the Roman Empire, located in northern Syria), and southern Syria have also been suggested.[20][21] Theologian and former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams proposed that Libya was a possible setting, as it was the location of Cyrene and there is a long-held Arabic tradition of Mark's residence there.[22]

The consensus among modern scholars is that the gospels are a subset of the ancient genre of bios, or ancient biography.[23] Ancient biographies were concerned with providing examples for readers to emulate while preserving and promoting the subject's reputation and memory, and also included morals and rhetoric in their works.[24] Like all the synoptic gospels, the purpose of writing was to strengthen the faith of those who already believed, as opposed to serving as a tractate for missionary conversion.[25] Christian churches were small communities of believers, often based on households (an autocratic patriarch plus extended family, slaves, freedmen, and other clients), and the evangelists often wrote on two levels: one the "historical" presentation of the story of Jesus, the other dealing with the concerns of the author's own day. Thus the proclamation of Jesus in Mark 1:14 and the following verses, for example, mixes the terms Jesus would have used as a 1st-century Jew ("kingdom of God") and those of the early church ("believe", "gospel").[26]

Christianity began within Judaism, with a Christian "church" (or ἐκκλησία, ekklesia, meaning 'assembly') that arose shortly after Jesus's death when some of his followers claimed to have witnessed him risen from the dead.[27] From the outset, Christians depended heavily on Jewish literature, supporting their convictions through the Jewish scriptures.[28] Those convictions involved a nucleus of key concepts: the messiah, the son of God and the son of man, the suffering servant, the Day of the Lord, and the kingdom of God. Uniting these ideas was the common thread of apocalyptic expectation: Both Jews and Christians believed that the end of history was at hand, that God would very soon come to punish their enemies and establish his own rule, and that they were at the centre of his plans. Christians read the Jewish scripture as a figure or type of Jesus Christ, so that the goal of Christian literature became an experience of the living Christ.[29] The new movement spread around the eastern Mediterranean and to Rome and further west, and assumed a distinct identity, although the groups within it remained extremely diverse.[27]

Synoptic problem

[edit]

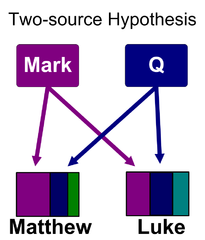

The gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke bear a striking resemblance to each other, so much so that their contents can easily be set side by side in parallel columns. The fact that they share so much material verbatim and yet also exhibit important differences has led to several hypotheses explaining their interdependence, a phenomenon termed the synoptic problem.

Up until the 19th century, the gospel of Mark was traditionally placed second, and sometimes fourth, in the Christian canon, and was believed to be an abridgement of Matthew. The Church has consequently derived its view of Jesus primarily from Matthew, secondarily from John, and only distantly from Mark. However, in the 19th century, a theory was developed known as Marcan priority, which held that Mark was the first of the four gospels written.[30] In this view, Mark was a source used by both Matthew and Luke, who agree with each other in their sequence of stories and events only when they also agree with Mark.[31] The hypothesis of Marcan priority is held by the majority of scholars today, and there is a new recognition of the author as an artist and theologian using a range of literary devices to convey his conception of Jesus as the authoritative yet suffering Son of God.[32]

Historicity

[edit]The idea of Marcan priority first gained widespread acceptance during the 19th century. From this position, it was generally assumed that Mark's provenance meant that it was the most reliable of the four gospels as a source for facts about the historical Jesus. However, the conceit that Mark could be used to reconstruct the historical Jesus suffered two severe blows in the early 20th century. Firstly, in 1901 William Wrede put forward an argument that the "Messianic Secret" motif within Mark had actually been a creation of the early church instead of a reflection of the historical Jesus. In 1919, Karl Ludwig Schmidt argued that the links between episodes in Mark were a literary invention of the author, meaning that the text could not be used as evidence in attempts to reconstruct the chronology of Jesus' mission.[33] The latter half of the 20th century saw a consensus emerge among scholars that the author of Mark had primarily intended to announce a message rather than to report history.[34] Nonetheless, Mark is generally seen as the most reliable of the four gospels in its overall description of Jesus' life and ministry.[35] Michael Patrick Barber has challenged the prevailing view, arguing that "Matthew's overall portrait presents us with a historically plausible picture..." of the Historical Jesus. Dale Allison had already argued that the Gospel of Matthew is more accurate than Mark in several regards, but was finally convinced by Barber's work to no longer regard the "uniquely Matthean" materials as ahistorical, declaring that the Historical Jesus "is not buried beneath Matthew but stares at us from its surface".[36] Matthew Thiessen wholeheartedly agrees as well, finding no fault in Barber's work.[37][e]

Structure and content

[edit]Detailed content of Mark

1. Galilean ministry

John the Baptist (1:1–8)

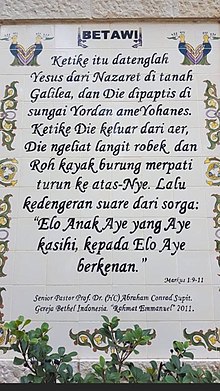

Baptism of Jesus (1:9–11)

Temptation of Jesus (1:12–13)

Return to Galilee (1:14)

Good News (1:15)

First disciples (1:16–20)

Capernaum's synagogue (1:21–28)

Peter's mother-in-law (1:29–31)

Exorcising at sunset (1:32–34)

A leper (1:35–45)

A paralytic (2:1–2:12)

Calling of Matthew (2:13–17)

Fasting and wineskins (2:18–22)

Lord of the Sabbath (2:23–28)

Man with withered hand (3:1–6)

Withdrawing to the sea (3:7–3:12)

Commissioning the Twelve (3:13–19)

Blind mute (3:20–26)

Strong man (3:27)

Eternal sin (3:28–30)

Jesus' true relatives (3:31–35)

Parable of the Sower (4:1–9,13-20)

Purpose of parables (4:10–12,33-34)

Lamp under a bushel (4:21–23)

Mote and Beam (4:24–25)

Growing seed and Mustard seed (4:26–32)

Calming the storm (4:35–41)

Demon named Legion (5:1–20)

Daughter of Jairus (5:21–43)

Hometown rejection (6:1–6)

Instructions for the Twelve (6:7–13)

Beheading of John (6:14–29)

Feeding the 5000 (6:30–44)

Walking on water (6:45–52)

Fringe of his cloak heals (6:53–56)

Discourse on Defilement (7:1–23)

Canaanite woman's daughter (7:24–30)

Deaf mute (7:31–37)

Feeding the 4000 (8:1–9)

No sign will be given (8:10–21)

Healing with spit (8:22–26)

Peter's confession (8:27–30)

Jesus predicts his death (8:31–33, 9:30–32, 10:32–34)

Instructions for followers (8:34–9:1)

Transfiguration (9:2–13)

Possessed boy (9:14–29)

Teaching in Capernaum (9:33–50)

2. Journey to Jerusalem

Entering Judea and Transjordan (10:1)

On divorce (10:2–12)

Little children (10:13–16)

Rich young man (10:17–31)

Son of man came to serve (10:35–45)

Blind Bartimaeus (10:46–52)

3. Events in Jerusalem

Entering Jerusalem (11:1–11)

Cursing the fig tree (11:12–14,20-24)

Temple incident (11:15–19)

Prayer for forgiveness (11:25–26)

Authority questioned (11:27–33)

Wicked husbandman (12:1–12)

Render unto Caesar... (12:13–17)

Resurrection of the Dead (12:18–27)

Great Commandment (12:28–34)

Is the Messiah the son of David? (12:35–40)

Widow's mite (12:41–44)

Olivet Discourse (13)

Plot to kill Jesus (14:1–2)

Anointing (14:3–9)

Bargain of Judas (14:10–11)

Last Supper (14:12–26)

Denial of Peter (14:27–31,66-72)

Agony in the Garden (14:32–42)

Kiss of Judas (14:43–45)

Arrest (14:46–52)

Before the High Priest (14:53–65)

Pilate's court (15:1–15)

Soldiers mock Jesus (15:16–20)

Simon of Cyrene (15:21)

Crucifixion (15:22–41)

Entombment (15:42–47)

Empty tomb (16:1–8)

The Longer Ending (16:9–20)

Post-resurrection appearances (16:9–13)

Great Commission (16:14–18)

Ascension (16:19)

Dispersion of the Apostles (16:20)

Structure

[edit]There is no agreement on the structure of Mark.[38] There is, however, a widely recognised break at Mark 8:26–31: before 8:26 there are numerous miracle stories, the action is in Galilee, and Jesus preaches to the crowds, while after 8:31 there are hardly any miracles, the action shifts from Galilee to gentile areas or hostile Judea, and Jesus teaches the disciples.[39] Peter's confession at Mark 8:27–30 that Jesus is the messiah thus forms the watershed to the whole gospel.[40] A further generally recognised turning point comes at the end of chapter 10, when Jesus and his followers arrive in Jerusalem and the foreseen confrontation with the Temple authorities begins, leading R.T. France to characterise Mark as a three-act drama.[41] James Edwards in his 2002 commentary points out that the gospel can be seen as a series of questions asking first who Jesus is (the answer being that he is the messiah), then what form his mission takes (a mission of suffering culminating in the crucifixion and resurrection, events only to be understood when the questions are answered), while another scholar, C. Myers, has made what Edwards calls a "compelling case" for recognising the incidents of Jesus' baptism, transfiguration and crucifixion, at the beginning, middle and end of the gospel, as three key moments, each with common elements, and each portrayed in an apocalyptic light.[42] Stephen H. Smith has made the point that the structure of Mark is similar to the structure of a Greek tragedy.[43]

Content

[edit]- Jesus is first announced as the Messiah and then later as the Son of God; he is baptised by John and a heavenly voice announces him as the Son of God; he is tested in the wilderness by Satan; John is arrested, and Jesus begins to preach the good news of the kingdom of God.

- Jesus gathers his disciples; he begins teaching, driving out demons, healing the sick, cleansing lepers, raising the dead, feeding the hungry, and giving sight to the blind; he delivers a long discourse in parables to the crowd, intended for the disciples, but they fail to understand; he performs mighty works, calming the storm and walking on water, but while God and demons recognise him, neither the crowds nor the disciples grasp his identity. He also has several run-ins with Jewish lawkeepers, especially in chapters 2–3.

- Jesus asks the disciples who people say he is, and then, "but you, who do you say I am?" Peter answers that he is the Christ, and Jesus commands him to silence; Jesus explains that the Son of Man must go to Jerusalem and be killed, but will rise again; Moses and Elijah appear with Jesus and God tells the disciples, "This is my son," but they remain uncomprehending.

- Jesus goes to Jerusalem, where he is hailed as one who "comes in the name of the Lord" and will inaugurate the "kingdom of David"; he drives those who buy and sell animals from the Temple and debates with the Jewish authorities; on the Mount of Olives he announces the coming destruction of the Temple, the persecution of his followers, and the coming of the Son of Man in power and glory.

- A woman perfumes Jesus' head with oil, and Jesus explains that this is a sign of his coming death; Jesus celebrates Passover with the disciples, declares the bread and wine to be his body and blood, and goes with them to Gethsemane to pray; there Judas betrays him to the Jewish authorities. Interrogated by the high priest, Jesus says that he is the Christ, the Son of God, and will return as Son of Man at God's right hand. The Jewish leaders turn him over to Pilate, who has him crucified as one who claims to be "king of the Jews"; Jesus, abandoned by the disciples, is buried in a rock tomb by a sympathetic member of the Jewish council.

- The women who have followed Jesus come to the tomb on Sunday morning; they find it empty, and are told by a young man in a white robe to go and tell the others that Jesus has risen and has gone before them to Galilee; "but they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid".[44]

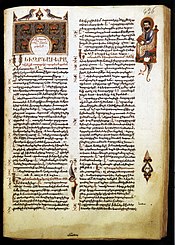

Ending

[edit]The earliest extant Greek manuscripts of Mark, codices Vaticanus (which contains a large blank space in the column after 16:8) and Sinaiticus, end at Mark 16:8, with the women fleeing in fear from the empty tomb. The majority of recent scholars believe this to be the original ending,[45] and that this is supported by statements from the early Church Fathers Eusebius and Jerome.[46] The "shorter ending", found in a small number of manuscripts, tells how the women told "those around Peter" all that the angel had commanded and how the message of eternal life (or "proclamation of eternal salvation") was then sent out by Jesus himself; it differs from the rest of Mark both in style and in its understanding of Jesus and is almost universally considered a spurious addition; the overwhelming majority of manuscripts have the "longer ending", with accounts of the resurrected Jesus, the commissioning of the disciples to proclaim the gospel, and Christ's ascension.[46] In deference to its importance within the manuscript tradition, the New Testament critical editors enclose the longer ending in brackets.[47]

Theology

[edit]

Gospel

[edit]The author introduces his work as "gospel", meaning "good news", a literal translation of the Greek "evangelion"[48] – he uses the word more often than any other writer in the New Testament except Paul.[49] Paul uses it to mean "the good news (of the saving significance of the death and resurrection) of Christ"; Mark extends it to the career of Christ as well as his death and resurrection.[48] Like the other gospels, Mark was written to confirm the identity of Jesus as eschatological deliverer – the purpose of terms such as "messiah" and "son of God". As in all the gospels, the messianic identity of Jesus is supported by a number of themes, including: (1) the depiction of his disciples as obtuse, fearful and uncomprehending; (2) the refutation of the charge made by Jesus' enemies that he was a magician; (3) secrecy surrounding his true identity (this last is missing from John).[50]

The failure of the disciples

[edit]In Mark, the disciples, especially the Twelve, move from lack of perception of Jesus to rejection of the "way of suffering" to flight and denial – even the women who received the first proclamation of his resurrection can be seen as failures for not reporting the good news. There is much discussion of this theme among scholars. Some argue that the author of Mark was using the disciples to correct "erroneous" views in his own community concerning the reality of the suffering messiah, others that it is an attack on the Jerusalem branch of the church for resisting the extension of the gospel to the gentiles, or a mirror of the convert's usual experience of the initial enthusiasm followed by growing awareness of the necessity for suffering. It certainly reflects the strong theme in Mark of Jesus as the "suffering just one" portrayed in so many of the books of the Jewish scriptures, from Jeremiah to Job and the Psalms, but especially in the "Suffering Servant" passages in Isaiah. It also reflects the Jewish scripture theme of God's love being met by infidelity and failure, only to be renewed by God. The failure of the disciples and Jesus' denial by Peter himself would have been powerful symbols of faith, hope and reconciliation for Christians.[51]

The charge of magic

[edit]Mark contains twenty accounts of miracles and healings, accounting for almost a third of the gospel and half of the first ten chapters, more, proportionally, than in any other gospel.[52] In the gospels as a whole, Jesus' miracles, prophecies, etc., are presented as evidence of God's rule, but Mark's descriptions of Jesus' healings are a partial exception to this, as his methods, using spittle to heal blindness[53] and magic formulae,[54] were those of a magician.[55][56] This is the charge the Jewish religious leaders bring against Jesus: they say he is performing exorcisms with the aid of an evil spirit[57] and calling up the spirit of John the Baptist.[58][55] "There was [...] no period in the history of the [Roman] empire in which the magician was not considered an enemy of society," subject to penalties ranging from exile to death, says Classical scholar Ramsay MacMullen.[59] All the gospels defend Jesus against the charge, which, if true, would contradict their ultimate claims for him. The point of the Beelzebub incident in Mark[60] is to set forth Jesus' claims to be an instrument of God, not Satan.[61]

Messianic Secret

[edit]In 1901, William Wrede identified the "Messianic Secret" – Jesus' secrecy about his identity as the messiah – as one of Mark's central themes. Wrede argued that the elements of the secret – Jesus' silencing of the demons, the obtuseness of the disciples regarding his identity, and the concealment of the truth inside parables – were fictions and arose from the tension between the Church's post-resurrection messianic belief and the historical reality of Jesus. There remains continuing debate over how far the "secret" originated with Mark and how far he got it from tradition, and how far, if at all, it represents the self-understanding and practices of the historical Jesus.[62]

Christology

[edit]Christology means a doctrine or understanding concerning the person or nature of Christ.[63] In the New Testament writings it is frequently conveyed through the titles applied to Jesus. Most scholars agree that "Son of God" is the most important of these titles in Mark. It appears on the lips of God himself at the baptism and the transfiguration, and is Jesus' own self-designation.[64] These and other instances provide reliable evidence of how the evangelist perceived Jesus, but it is not clear just what the title meant to Mark and his 1st-century audience.[65] Where it appears in the Hebrew scriptures it meant Israel as God's people, or the king at his coronation, or angels, as well as the suffering righteous man.[66] In Hellenistic culture the same phrase meant a "divine man", a supernatural being. There is little evidence that "son of God" was a title for the messiah in 1st century Judaism, and the attributes that Mark describes in Jesus are much more those of the Hellenistic miracle-working "divine man" than of the Jewish Davidic messiah.[65]

Mark does not explicitly state what he means by "Son of God", nor when the sonship was conferred.[67] The New Testament as a whole presents four different understandings:

- Jesus became God's son at his resurrection, God "begetting" Jesus to a new life by raising him from the dead – this was the earliest understanding, preserved in Paul's Epistle to the Romans, 1:3–4, and in Acts 13:33;

- Jesus became God's son at his baptism, the coming of the Holy Spirit marking him as messiah, while "Son of God" refers to the relationship then established for him by God – this is the understanding implied in Mark 1:9–11;[68]

- Matthew and Luke present Jesus as "Son of God" from the moment of conception and birth, with God taking the place of a human father;

- John, the last of the gospels, presents the idea that the Christ was pre-existent and became flesh as Jesus – an idea also found in Paul.[69]

However, other scholars dispute this interpretation and instead hold that Jesus is already presented as God's son even before his baptism in Mark.[70]

Mark also calls Jesus "christos" (Christ), translating the Hebrew "messiah," (anointed person).[71] In the Old Testament the term messiah ("anointed one") described prophets, priests and kings; by the time of Jesus, with the kingdom long vanished, it had come to mean an eschatological king (a king who would come at the end of time), one who would be entirely human though far greater than all God's previous messengers to Israel, endowed with miraculous powers, free from sin, ruling in justice and glory (as described in, for example, the Psalms of Solomon, a Jewish work from this period).[72] The most important occurrences are in the context of Jesus' death and suffering, suggesting that, for Mark, Jesus can only be fully understood in that context.[71]

A third important title, "Son of Man", has its roots in Ezekiel, the Book of Enoch, (a popular Jewish apocalyptic work of the period), and especially in Daniel 7:13–14, where the Son of Man is assigned royal roles of dominion, kingship and glory.[73][74] Mark 14:62 combines more scriptural allusions: before he comes on clouds[75] the Son of Man will be seated on the right hand of God,[76] pointing to the equivalence of the three titles, Christ, Son of God, Son of Man, the common element being the reference to kingly power.[77]

Christ's death, resurrection and return

[edit]Eschatology means the study of the end-times, and the Jews expected the messiah to be an eschatological figure, a deliverer who would appear at the end of the age to usher in an earthly kingdom.[78] The earliest Jewish Christian community saw Jesus as a messiah in this Jewish sense, a human figure appointed by God as his earthly regent; but they also believed in Jesus' resurrection and exaltation to heaven, and for this reason they also viewed him as God's agent (the "son of God") who would return in glory ushering in the Kingdom of God.[79]

The term "Son of God" likewise had a specific Jewish meaning, or range of meanings,[80] including referring to an angel, the nation of Israel, or simply a man.[81][82] One of the most significant Jewish meanings of this epithet is a reference to an earthly king adopted by God as his son at his enthronement, legitimizing his rule over Israel.[83] In Hellenistic culture, in contrast, the phrase meant a "divine man", covering legendary heroes like Hercules, god-kings like the Egyptian pharaohs, or famous philosophers like Plato.[84] When the gospels call Jesus "Son of God" the intention is to place him in the class of Hellenistic and Greek divine men, the "sons of God" who were endowed with supernatural power to perform healings, exorcisms and other wonderful deeds.[83] Mark's "Son of David" is Hellenistic, his Jesus predicting that his mission involves suffering, death and resurrection, and, by implication, not military glory and conquest.[85] This reflects a move away from the Jewish-Christian apocalyptic tradition and towards the Hellenistic message preached by Paul, for whom Christ's death and resurrection, rather than the establishment of the apocalyptic Jewish kingdom, is the meaning of salvation, the "gospel".[79]

Comparison with other writings

[edit]

Mark and the New Testament

[edit]All four gospels tell a story in which Jesus' death and resurrection are the crucial redemptive events.[86] There are, however, important differences between the four: Unlike John, Mark never calls Jesus "God", or claims that Jesus existed before his earthly life; unlike Matthew and Luke, the author does not mention a virgin birth or indicate whether Jesus had a normal human parentage and birth; unlike Matthew and Luke, he makes no attempt to trace Jesus' ancestry back to King David or Adam with a genealogy.[87]

Christians of Mark's time expected Jesus to return as Messiah in their own lifetime – Mark, like the other gospels, attributes the promise to return to Jesus himself,[88] and it is reflected in the Pauline Epistles, the Epistle of James, the Epistle to the Hebrews and in the Book of Revelation. When return failed, the early Christians revised their understanding. Some acknowledged that the Second Coming had been delayed, but still expected it; others redefined the focus of the promise, the Gospel of John, for example, speaking of "eternal life" as something available in the present; while still others concluded that Jesus would not return at all (the Second Epistle of Peter argues against those who held the view that Jesus would not return at all).[89] Other scholars, however, contend that all four gospels show an eschatology wherein many of the eschatological topics concern the destruction of the Jewish Temple, the transfiguration and resurrection of Jesus, whereas his return is a promise for an undisclosed time in the future which people should always be ready for.[90][91][92][93] Other scholars, like those of the Jesus Seminar, believe that the apocalyptic language in Mark and the rest of the gospels are inventions of the gospel writers and the early Christians for theological and cultural purposes.[94]

Mark's despairing death of Jesus was changed to a more victorious one in subsequent gospels.[95] Mark's Christ dies with the cry, "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?"; Matthew, the next gospel to be written, repeats this word for word but manages to make clear that Jesus's death is the beginning of the resurrection of Israel; Luke has a still more positive picture, replacing Mark's (and Matthew's) cry of despair with one of submission to God's will ("Father, into your hands I commend my spirit"); while John, the last gospel, has Jesus dying without apparent suffering in fulfillment of the divine plan.[95]

Content unique to Mark

[edit]

- The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath. Mark 2:27[f] Not present in either Matthew 12:1–8 or Luke 6:1–5. This is also a so-called "Western non-interpolation". The passage is not found in the Western text of Mark.

- People were saying, "[Jesus] has gone out of his mind", see also Rejection of Jesus.[96]

- Mark is the only gospel with the combination of verses in Mark 4:24–25: the other gospels split them up, Mark 4:24 being found in Luke 6:38 and Matthew 7:2, Mark 4:25 in Matthew 13:12 and Matthew 25:29, Luke 8:18 and Luke 19:26.

- The Parable of the Growing Seed.[97]

- Only Mark counts the possessed swine; there are about two thousand.[98]

- Two consecutive healing stories of women; both make use of the number twelve.[99]

- Only Mark gives healing commands of Jesus in the (presumably original) Aramaic: Talitha koum,[100] Ephphatha.[101] See Aramaic of Jesus.

- Only place in the New Testament where Jesus is referred to as "the son of Mary".[102]

- Mark is the only gospel where Jesus himself is called a carpenter;[102] in Matthew he is called a carpenter's son.[103]

- Only place that both names his brothers and mentions his sisters;[102] Matthew has a slightly different name for one brother.[103]

- The taking of a staff and sandals is permitted in Mark 6:8–9 but prohibited in Matthew 10:9–10 and Luke 9:3.

- Only Mark refers to Herod Antipas as a king;[104] Matthew and Luke refer to him (more properly) as a tetrarch.[105]

- The longest version of the story of Herodias' daughter's dance and the beheading of John the Baptist.[106]

- Mark's literary cycles:

- 6:30–44 – Feeding of the five thousand;

- 6:45–56 – Crossing of the lake;

- 7:1–13 – Dispute with the Pharisees;

- 7:14–23 – Discourse on Defilement[107]

- Then:

- 8:1–9 – Feeding of the four thousand;

- 8:10 – Crossing of the lake;

- 8:11–13 – Dispute with the Pharisees;

- 8:14–21 – Incident of no bread and discourse about the leaven of the Pharisees.

- Customs that at that time were unique to Jews are explained (hand, produce, and utensil washing): Mark 7:3–4.

- "Thus he declared all foods clean".[g] 7:19 NRSV, not found in the Matthean parallel Matthew 15:15–20.

- There is no mention of Samaritans.

- Jesus heals using his fingers and spit at the same time: 7:33; cf. 8:23, Luke 11:20, John 9:6, Matthew 8:16.

- Jesus lays his hands on a blind man twice in curing him: 8:23–25; cf. 5:23, 16:18, Acts 6:6, Acts 9:17, Acts 28:8, laying on of hands.

- Jesus cites the Shema Yisrael: "Hear O Israel ...";[108] in the parallels of Matt 22:37–38 and Luke 10:27 the first part of the Shema[109] is absent.

- Mark points out that the Mount of Olives is across from the Temple.[110]

- When Jesus is arrested, a naked young man flees.[111] A young man in a robe also appears in Mark 16:5–7.

- Mark does not name the High Priest.[112]

- Witness testimony against Jesus does not agree.[113]

- The cock crows "twice" as predicted.[114] See also Fayyum Fragment. The other Gospels simply record, "the cock crew". Early codices 01, W, and most Western texts have the simpler version.[115]

- Pilate's position (Governor) is not specified.[116]

- Simon of Cyrene's sons are named.[117]

- A summoned centurion is questioned.[118]

- The women ask each other who will roll away the stone.[119]

- A young man sits on the "right side".[120]

- Mark is the only canonical gospel with significant various alternative endings.[h] Most of the contents of the traditional "Longer Ending" (Mark 16:9–20) are found in other New Testament texts and are not unique to Mark, see Mark 16 § Longer ending, the one significant exception being 16:18b ("and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them"), which is unique to Mark.

See also

[edit]

| Gospel of Mark |

|---|

- Acts of the Apostles (genre)

- Apocalyptic literature

- Gospel harmony

- Gospel of Mark (intertextuality)

- List of Gospels

- List of omitted Bible verses

- Sanhedrin Trial of Jesus (reference to Mark)

- Secret Gospel of Mark

- Textual variants in the Gospel of Mark

- Two-source hypothesis

Notes

[edit]- ^ The book is sometimes called the Gospel according to Mark (Ancient Greek: Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Μᾶρκον, romanized: Euangélion katà Mârkon), or simply Mark[1] (which is also its most common form of abbreviation).[2]

- ^ Adela Yarbro Collins, a Biblical scholar at Yale Divinity School, notes that Paul's letter to Philemon also mentions a Mark, which may be the same as the Mark from Acts. While it may be possible that the Gospel of Mark was written by this Mark, many scholars argue against this possibility, given the contradictions between Paul and Mark's theology and literary aspects.[11]

- ^ Leander 2013, p. 167 refers to Hengel 1985, pp. 7–28 and Collins 2007, pp. 11–14 as arguing for a dating immediately before 70 AD, and to Theissen 1992, pp. 258–262, Incigneri 2003, pp. 116–155, Head 2004 and Kloppenborg 2005 as arguing for a dating immediately after 70 AD. Leander also refers to the minority position of Crossley 2004, who proposed a much earlier c. 35–45 AD dating, listing reviews that point out the problems with Crossley's argument.

- ^ Thiessen: "Barber concludes that the Gospel of Matthew provides a historically plausible depiction of Jesus, regardless of the historical veracity of this or that precise detail. This remembered Jesus, the only Jesus we have access to [...] was a temple-pious Jew [...]it is this Jesus who makes sense of the various shapes that the early Jesus movement took"

- ^ Similar to a rabbinical saying from the 2nd century BC, "The Sabbath is given over to you ["the son of man"], and not you to the Sabbath." (Kohler 1905)

- ^ The verb katharizo means both "to declare to be clean" and "to purify." The Scholars Version has: "This is how everything we eat is purified", Gaus' Unvarnished New Testament has: "purging all that is eaten."

- ^ See Mark 16 § Alternate endings

References

[edit]- ^ ESV Pew Bible. Wheaton, IL: Crossway. 2018. p. 836. ISBN 978-1-4335-6343-0. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Bible Book Abbreviations". Logos Bible Software. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Boring 2006, pp. 44.

- ^ Elliott 2014, pp. 404–406.

- ^ Boring 2006, pp. 252–53.

- ^ a b Keith 2016, p. 92.

- ^ a b c Sanders 1995, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c d Burkett 2002, p. 156.

- ^ a b c Watts Henderson 2018, p. 1431.

- ^ a b Leander 2013, p. 167.

- ^ Collins 2007, p. 5-6.

- ^ Telford 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Levering, Matthew (2024). "The Historical Jesus and the Temple: Memory, Methodology, and the Gospel of Matthew by Michael Patrick Barber (review)". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 22–3 (3): 1053–1059. doi:10.1353/nov.2024.a934941.

- ^ van Os, Bas (2011). Psychological Analyses and the Historical Jesus: New Ways to Explore Christian Origins. T&T Clark. pp. 57, 83. ISBN 978-0567269515.

- ^ Bockmuehl, Markus (2006). Seeing the Word: Refocusing New Testament Study. Baker Academic. pp. 178–184. ISBN 978-0801027611.

- ^ Boring 2006, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Dunn 2003, pp. 203.

- ^ James D.G. Dunn, "Messianic Ideas and Their Influence on the Jesus of History," in The Messiah, ed. James H. Charlesworth. pp. 371–372. Cf. James D.G. Dunn, Jesus Remembered.

- ^ Rodriguez, Rafael (2010). Structuring Early Christian Memory: Jesus in Tradition, Performance and Text. T&T Clark. pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-0567264206.

- ^ Perkins 2007, p. 241.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 157.

- ^ Williams, Rowan (2014). Meeting God in Mark. p. 17.

- ^ Lincoln 2004, p. 133.

- ^ Dunn 2005, p. 174.

- ^ Aune 1987, p. 59.

- ^ Aune 1987, p. 60.

- ^ a b Lössl 2010, p. 43.

- ^ Gamble 1995, p. 23.

- ^ Collins 2000, p. 6.

- ^ Edwards 2002, p. 2.

- ^ Koester 2000, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Edwards 2002, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Joel 2000, p. 859.

- ^ Williamson 1983, p. 17.

- ^ Powell 1998, p. 37.

- ^ Allison, Dale C. Jr. (2023). Foreword. The Historical Jesus and the Temple: Memory, Methodology and the Gospel of Matthew. By Barber, Michael Patrick. Cambridge University Press. pp. x, 238. ISBN 978-1-009-21085-0.

- ^ Thiessen, Matthew (2024). "The Historical Jesus and the Temple: Memory, Methodology, and the Gospel of Matthew by Michael Patrick Barber (review)". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 86–1: 168. doi:10.1353/cbq.2024.a918386.

- ^ Twelftree 1999, p. 68.

- ^ Cole 1989, p. 86.

- ^ Cole 1989, pp. 86–87.

- ^ France 2002, p. 11.

- ^ Edwards 2002, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Smith 1995, pp. 209–31.

- ^ Boring 2006, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Edwards 2002, pp. 500–01.

- ^ a b Schröter 2010, p. 279.

- ^ Metzger 2000, pp. 105, 106.

- ^ a b Aune 1987, p. 17.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 95.

- ^ Aune 1987, p. 55.

- ^ Donahue 2005, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Twelftree 1999, p. 57.

- ^ Bible Mark 8:22–26

- ^ "Talitha cumi," 5:41, "Ephphatha," 7:34

- ^ a b Kee 1993, p. 483.

- ^ Powell 1998, p. 57.

- ^ Bible Mark 3:22

- ^ Bible Mark 6:14

- ^ Welch 2006, p. 362.

- ^ Bible Mark 3:20–30

- ^ Aune 1987, p. 56.

- ^ Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 1083.

- ^ Telford 1999, p. 3.

- ^ Bible Mark 13:32

- ^ a b Telford 1999, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Donahue 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Ehrman 1993, p. 74.

- ^ Bible Mark 1:9–11

- ^ Burkett 2002, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Hurtado 2021, p. 96.

- ^ a b Donahue 2005, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Edwards 2002, p. 250.

- ^ Witherington 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Donahue 2005, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Bible Daniel 7:13

- ^ Bible Psalm 110:1

- ^ Witherington 2001, p. 52.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 69.

- ^ a b Telford 1999, p. 155.

- ^ Dunn 2003, pp. 709–10.

- ^ Grossman 2011, p. 698.

- ^ Levine & Brettler 2011, p. 544.

- ^ a b Strecker 2000, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Dunn 2003, p. 69.

- ^ Telford 1999, p. 52.

- ^ Hurtado 2005, p. 587.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 158.

- ^ Bible Mark 9:1 and 13:30

- ^ Burkett 2002, pp. 69–70.

- ^ N.T. Wright (2018), Hope Deferred? Against the Dogma of Delay, University of St. Andrew's, pp. 68-72

- ^ Larry Hurtado (1990), Mark: New International Biblical Commentary, p. 140

- ^ Robert Stein (2014), Jesus, the Temple and the Coming Son of Man: A Commentary on Mark 13

- ^ Michael F. Bird (2024), The Olivet Discourse: Second Coming Prophesy or Prophetic Warning against Jerusalem?

- ^ Borg, Marcus J. (October 1988). "A renaissance in Jesus studies". Princeton Theological Seminary. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012.

- ^ a b Moyise 2013, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Bible Mark 3:21

- ^ Bible Mark 4:26–29

- ^ Bible Mark 5:13

- ^ Bible Mark 5:25, Mark 5:42

- ^ Bible Mark 5:41

- ^ Bible Mark 7:34

- ^ a b c Bible Mark 6:3

- ^ a b Bible Matthew 13:55

- ^ Bible Mark 6:14, Mark 6:24

- ^ Bible cf. Matthew 14:1; Luke 3:19, Luke 9:7

- ^ Bible Mark 6:14–29

- ^ Twelftree 1999, p. 79.

- ^ Bible Mark 12:29–30

- ^ Bible Deut 6:4

- ^ Bible Mark 13:3

- ^ Bible Mark 14:51–52

- ^ Bible cf. Matthew 26:57, Luke 3:2, Acts 4:6, John 18:13

- ^ Bible cf. Mark 14:56, Mark 14:59

- ^ Bible Mark 14:72

- ^ Willker, Wieland. "A Textual Commentary on the Greek Gospels. Vol. 2: Mark, p. 448" (PDF). TCG 2007: An Online Textual Commentary on the Greek Gospels (5th ed.). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- ^ Bible cf. Mark 15:1, Matthew 27:2, Luke 3:1, John 18:28–29

- ^ Bible Mark 15:21

- ^ Bible Mark 15:44–45

- ^ Bible cf. Mark 16:3, Matthew 28:2–7

- ^ Bible cf. Mark 16:5, Luke 24:4, John 20:12

Sources

[edit]- Aune, David E. (1987). The New Testament in its Literary Environment. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25018-8.

- Boring, M. Eugene (2006). Mark: A Commentary. Presbyterian Publishing Corp. ISBN 978-0-664-22107-2.

- Brown, Raymond E. (1997). An Introduction to the New Testament. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-24767-2.

- Burkett, Delbert (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00720-7.

- Cole, R. Alan (1989). The Gospel According to Mark: An Introduction and Commentary (2 ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-0481-5.

- Collins, Adela Yarbro (2000). Cosmology and Eschatology in Jewish and Christian Apocalypticism. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11927-7.

- Collins, Adela Yarbro (2007). Mark: A Commentary. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

- Charlesworth, James (2013). The Tomb of Jesus and His Family?: Exploring Ancient Jewish Tombs Near Jerusalem's Walls. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-6745-2.

- Cross, Frank L.; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds. (2005) [1997]. "Messianic Secret". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 1083. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- Crossley, James G. (2004). The Date of Mark's Gospel: Insight from the Law in Earliest Christianity (The Library of New Testament Studies). T & T Clark International. ISBN 978-0567081957.

- Donahue, John R. (2005) [2002]. The Gospel of Mark. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5965-6.

- Dunn, James D.G. (2003). Jesus Remembered. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-3931-2.

- Dunn, James D.G. (2005). "The Tradition". In Dunn, James D.G.; McKnight, Scot (eds.). The Historical Jesus in Recent Research. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-100-9.

- Edwards, James (2002). The Gospel According to Mark. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85111-778-2.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1993). The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510279-6.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2004). The New Testament. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-515462-2.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2006). Peter, Paul and Mary Magdalene: The Followers of Jesus in History and Legend. Oxford University Press. pp. 6–10. ISBN 978-0-19-974113-7.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-19-975668-1.

Most scholars today have abandoned these identifications...

- Elliott, Neil (2014). "Messianic Secret". In Evans, Craig A. (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Routledge. ISBN 9781317722243.

- France, R.T. (2002). The Gospel of Mark: A Commentary on the Greek text. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2446-2.

- Gamble, Harry Y. (1995). Books and Readers in the Early Church: A History of Early Christian Texts. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06918-1.

- Goodacre, Mark (September 2021). Lawrence, Louise (ed.). "How Empty Was the Tomb?". Journal for the Study of the New Testament. 44 (1). SAGE Publications: 134–148. doi:10.1177/0142064X211023714. ISSN 1745-5294. S2CID 236233486.

- Grossman, Maxine (14 March 2011) [1997]. "Son of Man". In Berlin, Adele (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press, USA. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199730049.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-973004-9.

- Head, Ivan (2004). "Mark as a Roman Document from the Year 69: Testing Martin Hengel's Thesis". Journal of Religious History. 28 (3): 240–259. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.2004.00242.x.

- Hengel, Martin (1985). Studies in the Gospel of Mark. London: SCM.

- Horsely, Richard A. (2007). "Mark". In Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press. pp. 56–92 New Testament. ISBN 978-0-19-528881-0.

- Hurtado, Larry W. (2005) [2003]. Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-3167-5.

- Hurtado, Larry W. (2021). "Mark's Presentation of Jesus". In Kirk, J. R. Daniel; Winn, Adam; Huebenthal, Sandra; Hurtado, L. W. (eds.). Christology in Mark's Gospel: Four Views. Zondervan Academic. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-310-53872-1.

- Incigneri, Brian J. (2003). The Gospel to the Romans: The Setting and Rhetoric of Mark's Gospel. Biblical Interpretation Series. Vol. 65. Leiden: Brill.

- Iverson, Kelly R. (2011). "Wherever the Gospel Is Preached': The Paradox of Secrecy in the Gospel of Mark". In Iverson, Kelly R.; Skinner, Christopher W. (eds.). Mark as Story: Retrospect and Prospect. SBL. ISBN 9781589835481.

- Joel, Marcus (2000). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-90-5356-503-2.

- Kee, Howard Clark (1993). "Magic and Divination". In Coogan, Michael David; Metzger, Bruce M. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. pp. 483–84. ISBN 978-0-19-504645-8.

- Keith, Chris (2016). "The Pericope Adulterae: A theory of attentive insertion". In Black, David Alan; Cerone, Jacob N. (eds.). The Pericope of the Adulteress in Contemporary Research. The Library of New Testament Studies. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-567-66580-5.

- Kloppenborg, John S. (2005). "Evocatio deorum and the Date of Mark". Journal of Biblical Literature. 124 (3): 419–450. doi:10.2307/30041033. JSTOR 30041033.

- Koester, Helmut (2000) [1982]. Introduction to the New Testament: History and literature of early Christianity (2 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-0-567-16561-9.

- Kohler, Kaufmann (1905). "New Testament". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. p. 246-254.

- Leander, Hans (2013). Discourses of Empire: The Gospel of Mark from a Postcolonial Perspective. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-889-5.

- Levine, Amy-Jill; Brettler, Marc Z. (3 November 2011). The Jewish Annotated New Testament. Oxford: OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-529770-6.

- Lincoln, Andrew (2004). "Reading John". In Porter, Stanley E. (ed.). Reading the Gospels Today. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-0517-1.

- Lössl, Josef (2010). The Early Church: History and Memory. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-567-16561-9.

- Metzger, Bruce M. (2000). A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (2nd ed.). Germany: United Bible Societies. ISBN 3-438-06010-8.

- Morris, Leon (1990) [1986]. New Testament Theology. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-45571-4.

- Moyise, Steve (2013). Introduction to Biblical Studies. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-18926-4.

- Perkins, Pheme (1998). "The Synoptic Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles: Telling the Christian Story". In Barton, John (ed.). The Cambridge companion to biblical interpretation. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 241–58. ISBN 978-0-521-48593-7.

- Perkins, Pheme (2007). Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-6553-3.

- Powell, Mark Allan (1998). Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-664-25703-3.

- Reddish, Mitchell (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels. Abingdon Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1-4267-5008-3.

- Roskam, H.N. (2004). The purpose of the Gospel of Mark in its historical and social context. Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-1394-3.

- Sanders, E (1995). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141928227.

- Schröter, Jens [in German] (2010). "The Gospel of Mark". In Aune, David E. (ed.). The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide. Wiley–Blackwell. pp. 272–95. ISBN 978-1-4051-0825-6.

- Smith, Stephen H. (1995). "A Divine Tragedy: Some Observations on the Dramatic Structure of Mark's Gospel". Novum Testamentum. 37 (3). E.J. Brill, Leiden: 209–31. doi:10.1163/1568536952662709. JSTOR 1561221.

- Strauss, Mark L. (2014). Mark. Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament. Vol. 2. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-24358-8. OCLC 863695341.

- Strecker, Georg [in German] (2000). Theology of the New Testament. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-0-664-22336-6.

- Telford, William R. (1999). The Theology of the Gospel of Mark. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43977-0.

- Theissen, Gerd (1992). The Gospels in Context: Social and Political History in the Synoptic Tradition. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Twelftree, Graham H. (1999). Jesus the miracle worker: a historical & theological study. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1596-8.

- Watts Henderson, Suzanne (2018). "The Gospel according to Mark". In Coogan, Michael; Brettler, Marc; Newsom, Carol; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-027605-8.

- Welch, John W. (2006). "Miracles, Maleficium, and Maiestas in the Trial of Jesus". In Charlesworth, James H. (ed.). Jesus and Archaeology. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-4880-2.

- Williams, Guy J. (March 2013). Lawrence, Louise (ed.). "Narrative Space, Angelic Revelation, and the End of Mark's Gospel". Journal for the Study of the New Testament. 35 (3). SAGE Publications: 263–284. doi:10.1177/0142064X12472118. ISSN 1745-5294. S2CID 171065040.

- Williamson, Lamar (1983). Mark. John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23760-8.

- Winn, Adam (2008). The purpose of Mark's gospel. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-149635-6.

- Witherington, Ben (2001). The Gospel of Mark: A Socio-rhetorical Commentary. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-4503-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Beaver, Caurie (2009). Mark: A Twice-Told Story. Wipf and Stoc. ISBN 978-1-60899-121-1.

- Brown, Raymond E. (1994). An Introduction to New Testament Christology. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-3516-5.

- Crossan, John Dominic (2010) [1998]. The Birth of Christianity: Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately After the Execution of Jesus. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-197815-9.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Misquoting Jesus. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-085951-0.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2009). Jesus Interrupted. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-117394-3.

- Ladd, George Eldon (1993). A Theology of the New Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-0680-2.

- Lane, William L. (1974). The Gospel According to Mark: The English Text with Introduction, Exposition and Notes. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2502-5.

- Levine, Amy-Jill (2001) [1998]. "Visions of kingdoms: From Pompey to the first Jewish revolt". In Coogan, Michael D. (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2.

- Mack, Burton L. (1994) [1993]. The Lost Gospel: The Book of Q and Christian origins. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-065375-0.

- Marcus, Joel (2002). Mark 1–8. Anchor Bible Series. Yale University Press.

- Marcus, Joel (2009). Mark 8–16. Anchor Bible Series. Yale University Press.

- Perrin, Norman; Duling, Dennis C. (1982). The New Testament: An Introduction (2 ed.). Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0-15-565726-7.

- Robinson, John A.T. (2000). Redating the New Testament. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1579105273.

- Schnelle, Udo (1998). The History and Theology of the New Testament Writings. Translated by M. Eugene Boring. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-2952-6.

- Theißen, Gerd; Merz, Annette (1998). The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide. Augsburg Fortress. ISBN 978-0-8006-3123-9.

- Van Linden, Philip (1992) [1989]. "Mark". In Karris, Robert J. (ed.). The Collegeville Bible Commentary: New Testament, NAB. Liturgical Press. pp. 903–35. ISBN 978-0-8146-2211-7.

- Weeden, Theodore J. (1995). "The Heresy that Necessitated Mark's Gospel". In Telford, William (ed.). Interpretation of Mark. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-567-29256-8.

- Willker, Wieland (2015). Mark (PDF). A Textual Commentary on the Greek Gospels. Vol. 2 (12th ed.). Bremen, Germany: Author. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- Winn, Adam (2008). The Purpose of Mark's Gospel: An Early Christian Response to Roman Imperial Propaganda. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3161496356.

External links

[edit]Online translations of the Gospel of Mark

- Bible Gateway: 94 languages/219 versions

- Bible Hub: 43 languages/101 versions

- Wikisource: 1 language/23 versions

- oremus Bible Browser: 1 language/3 versions

Bible: Mark public domain audiobook at LibriVox: 1 language/8 versions

Bible: Mark public domain audiobook at LibriVox: 1 language/8 versions

Related articles

- Early Christian Writings: On-line scholarly resources

- Resources for the Book of Mark at The Text This Week