Thích Nhất Hạnh

Thích Nhất Hạnh | |

|---|---|

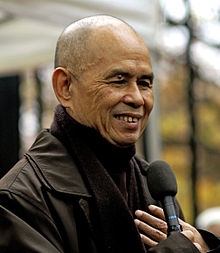

Nhất Hạnh in Paris in 2006 | |

| Title | Thiền Sư (Zen master) |

| Personal life | |

| Born | Nguyễn Xuân Bảo 11 October 1926 |

| Died | 22 January 2022 (aged 95) Huế, Thừa Thiên-Huế Province, Vietnam |

| Known for | Engaged Buddhism, father of the mindfulness movement |

| Other names | Nguyễn Đình Lang |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Thiền Buddhism |

| School | Linji school (Lâm Tế)[1] Order of Interbeing Plum Village Tradition |

| Lineage | 42nd generation (Lâm Tế)[1] 8th generation (Liễu Quán)[1] |

| Dharma names | Phùng Xuân, Điệu Sung |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Thích Chân Thật |

| Based in | Plum Village Monastery |

| Part of a series on |

| Zen Buddhism |

|---|

|

Thích Nhất Hạnh (/ˈtɪk ˈnɑːt ˈhɑːn/ TIK NAHT HAHN; Vietnamese: [tʰǐk̟ ɲə̌t hâjŋ̟ˀ] ⓘ, Huế dialect: [tʰɨt̚˦˧˥ ɲək̚˦˧˥ hɛɲ˨˩ʔ]; born Nguyễn Xuân Bảo; 11 October 1926 – 22 January 2022) was a Vietnamese Thiền Buddhist monk, peace activist, prolific author, poet and teacher,[2] who founded the Plum Village Tradition, historically recognized as the main inspiration for engaged Buddhism.[3] Known as the "father of mindfulness",[4] Nhất Hạnh was a major influence on Western practices of Buddhism.[2]

In the mid-1960s, Nhất Hạnh co-founded the School of Youth for Social Services and created the Order of Interbeing.[3] He was exiled from South Vietnam in 1966 after expressing opposition to the war and refusing to take sides.[2][5][6] In 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. nominated him for a Nobel Peace Prize.[7][2] Nhất Hạnh established dozens of monasteries and practice centers[2] and spent many years living at the Plum Village Monastery, which he founded in 1982 in southwest France near Thénac,[8] traveling internationally to give retreats and talks. Nhất Hạnh promoted deep listening as a nonviolent solution to conflict and sought to raise awareness of the interconnectedness of environments that sustain and promote peace.[9] He coined the term "engaged Buddhism" in his book Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire.[10]

After a 39-year exile, Nhất Hạnh was permitted to visit Vietnam in 2005.[5] In 2018, he returned to Vietnam to his "root temple", Từ Hiếu Temple, near Huế,[11] where he lived until his death in 2022, at the age of 95.[12]

Early life

[edit]Nhất Hạnh was born Nguyễn Xuân Bảo on 11 October 1926, in the ancient capital of Huế in central Vietnam.[13][7][14] He is 15th generation Nguyễn Đình; the poet Nguyễn Đình Chiểu, author of Lục Vân Tiên, was his ancestor.[15] His father, Nguyễn Đình Phúc, from Thành Trung village in Thừa Thiên, Huế, was an official with the French administration.[15] His mother, Trần Thị Dĩ, was a homemaker[7] from Gio Linh district.[15] Nhất Hạnh was the fifth of their six children.[15] Until he was age five, he lived with his large extended family at his grandmother's home.[15] He recalled feeling joy at age seven or eight after he saw a drawing of a peaceful Buddha, sitting on the grass.[14][7] On a school trip, he visited a mountain where a hermit lived who was said to sit quietly day and night to become peaceful like the Buddha. They explored the area, and he found a natural well, which he drank from and felt completely satisfied. It was this experience that led him to want to become a Buddhist monk.[6] At age 12, he expressed an interest in training to become a monk, which his parents, cautious at first, eventually let him pursue at age 16.[14]

Names applied to him

[edit]Nhất Hạnh had many names in his lifetime. As a boy, he received a formal family name (Nguyễn Đình Lang) to register for school, but was known by his nickname (Bé Em). He received a spiritual name (Điệu Sung) as an aspirant for the monkhood; a lineage name (Trừng Quang) when he formally became a lay Buddhist; and when he ordained as a monk he received a Dharma name (Phùng Xuân). He took the Dharma title Nhất Hạnh when he moved to Saigon in 1949.[16]

The Vietnamese name Thích (釋) is from "Thích Ca" or "Thích Già" (釋迦, "of the Shakya clan").[17] All Buddhist monastics in East Asian Buddhism adopt this name as their surname, implying that their first family is the Buddhist community. In many Buddhist traditions, a person can receive a progression of names. The lineage name is given first when a person takes refuge in the Three Jewels. Nhất Hạnh's lineage name is Trừng Quang (澄光, "Clear, Reflective Light"). The second is a dharma name, given when a person takes vows or is ordained as a monastic. Nhất Hạnh's dharma name is Phùng Xuân (逢春, "Meeting Spring") and his dharma title is Nhất Hạnh.[17]

Neither Nhất (一) nor Hạnh (行), which approximate the roles of middle name and given name, was part of his name at birth. Nhất means "one", implying "first-class", or "of best quality"; Hạnh means "action", implying "right conduct", "good nature", or "virtue". He translated his Dharma names as "One" (Nhất) and "Action" (Hạnh). Vietnamese names follow this convention, placing the family name first, then the middle name, which often refers to the person's position in the family or generation, followed by the given name.[18]

Nhất Hạnh's followers called him Thầy ("master; teacher"), or Thầy Nhất Hạnh. Any Vietnamese monk in the Mahayana tradition can be addressed as "thầy", with monks addressed as thầy tu ("monk") and nuns addressed as sư cô ("sister") or sư bà ("elder sister"). He is also known as Thiền Sư Nhất Hạnh ("Zen Master Nhất Hạnh").[19]

Education

[edit]

At age 16, Nhất Hạnh entered the monastery at Từ Hiếu Temple, where his primary teacher was Zen Master Thanh Quý Chân Thật, who was from the 43rd generation of the Lâm Tế Zen school and the ninth generation of the Liễu Quán school.[13][20][14] He studied as a novice for three years and received training in Vietnamese traditions of Mahayana and Theravada Buddhism.[13] Here he also learned Chinese, English and French.[6] Nhất Hạnh attended Báo Quốc Buddhist Academy.[13][2] Dissatisfied with the focus at Báo Quốc Academy, which he found lacking in philosophy, literature, and foreign languages, Nhất Hạnh left in 1950[13] and took up residence in the Ấn Quang Pagoda in Saigon, where he was ordained as a monk in 1951.[14] He supported himself by selling books and poetry while attending Saigon University,[13] where he studied literature, philosophy, psychology, and science and received a degree in French and Vietnamese Literature.[21][22][23]

In 1955, Nhất Hạnh returned to Huế and served as the editor of Phật Giáo Việt Nam (Vietnamese Buddhism), the official publication of the General Association of Vietnamese Buddhists (Tổng Hội Phật Giáo Việt Nam) for two years before the publication was suspended as higher-ranking monks disapproved of his writing. He believed that this was due to his opinion that South Vietnam's various Buddhist organisations should unite. In 1956, while he was away teaching in Đà Lạt, his name was expunged from the records of Ấn Quang, effectively disowning him from the temple. In late 1957, Nhất Hạnh decided to go on retreat, and established a monastic "community of resistance" named Phương Bôi, in Đại Lao Forest near Đà Lạt. During this period, he taught at a nearby high school and continued to write, promoting the idea of a humanistic, unified Buddhism.[13]

From 1959 to 1961, Nhất Hạnh taught several short courses on Buddhism at various Saigon temples, including the large Xá Lợi Pagoda, where his class was cancelled mid-session and he was removed due to disapproval of his teachings. Facing further opposition from Vietnamese religious and secular authorities,[13] Nhất Hạnh accepted a Fulbright Fellowship[6] in 1960 to study comparative religion at Princeton University.[24] He studied at the Princeton Theological Seminary in 1961.[25][2] In 1962 he was appointed lecturer in Buddhism at Columbia University[14] and also taught as a lecturer at Cornell University.[2] By then he had gained fluency in French, Classical Chinese, Sanskrit, Pali and English, in addition to his native Vietnamese.[24]

Career

[edit]Activism in Vietnam 1963–1966

[edit]In 1963, after the military overthrow of the minority Catholic regime of President Ngo Dinh Diem, Nhất Hạnh returned to South Vietnam on 16 December 1963, at the request of Thich Tri Quang, the monk most prominent in protesting the religious discrimination of Diem, to help restructure the administration of Vietnamese Buddhism.[13] As a result of a congress, the General Association of Buddhists and other groups merged to form the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBCV) in January 1964, and Nhất Hạnh proposed that the executive publicly call for an end to the Vietnam War, help establish an institute for the study of Buddhism to train future leaders, and create a centre to train pacifist social workers based on Buddhist teaching.[13]

In 1964, two of Nhất Hạnh's students founded La Boi Press with a grant from Mrs. Ngo Van Hieu. Within two years, the press published 12 books, but by 1966, the publishers risked arrest and jail because the word "peace" was taken to mean communism.[26] Nhất Hạnh also edited the weekly journal Hải Triều Âm (Sound of the Rising Tide), the UBCV's official publication. He continually advocated peace and reconciliation, notably calling in September 1964, soon after the Gulf of Tonkin incident, for a peace settlement, and referring to the Viet Cong as brothers. The South Vietnamese government subsequently closed the journal.[13]

On 1 May 1966, at Từ Hiếu Temple, Nhất Hạnh received the "lamp transmission" from Zen Master Chân Thật, making him a dharmacharya (teacher)[17] and the spiritual head of Từ Hiếu and associated monasteries.[17][27]

Vạn Hanh Buddhist University

[edit]On 13 March 1964, Nhất Hạnh and the monks at An Quang Pagoda founded the Institute of Higher Buddhist Studies (Học Viện Phật Giáo Việt Nam), with the UBCV's support and endorsement.[13] Renamed Vạn Hanh Buddhist University, it was a private institution that taught Buddhist studies, Vietnamese culture, and languages, in Saigon. Nhất Hạnh taught Buddhist psychology and prajnaparamita literature there,[14] and helped finance the university by fundraising from supporters.[13]

School of Youth for Social Service (SYSS)

[edit]

(Sister True Emptiness)

In 1964, Nhất Hạnh co-founded[3] the School of Youth for Social Service (SYSS), a neutral corps of Buddhist peace workers who went into rural areas to establish schools, build healthcare clinics, and help rebuild villages.[8] The SYSS consisted of 10,000 volunteers and social workers who aided war-torn villages, rebuilt schools and established medical centers.[28] He left for the U.S. shortly afterwards and was not allowed to return, leaving Sister Chân Không in charge of the SYSS. Chân Không was central to the foundation and many of the activities of the SYSS, which organized medical, educational and agricultural facilities in rural Vietnam during the war.[29] Nhất Hạnh was initially given substantial autonomy to run the SYSS, which was initially part of Vạn Hạnh University. In April 1966, the Vạn Hạnh Students’ Union under the presidency of Phượng issued a "Call for Peace". Vice Chancellor Thích Minh Châu dissolved the students' union and removed the SYSS from the university's auspices.[13]

The Order of Interbeing

[edit]Nhất Hạnh created the Order of Interbeing (Vietnamese: Tiếp Hiện), a monastic and lay group, between 1964[8] and 1966.[24] He headed this group, basing it on the philosophical concept of interbeing and teaching it through the Five Mindfulness Trainings[30] and the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings.[31][3] The trainings were a modern adaptation of the traditional bodhisattva vows designed to support efforts to promote peace and rebuild war-torn villages.[32] Nhất Hạnh established the Order of Interbeing from a selection of six SYSS board members, three men and three women, who took a vow to practice the Fourteen Precepts of Engaged Buddhism.[33] He added a seventh member in 1981.[33]

In 1967, Nhat Chi Mai, one of the first six Order of Interbeing members, set fire to herself and burned to death in front of the Tu Nghiem Pagoda in Saigon as a peace protest after calling for an end to the Vietnam War.[3][34][35] On several occasions, Nhất Hạnh explained to Westerners that Thích Quảng Đức and other Vietnamese Buddhist monks who self-immolated during the Vietnam war did not perform acts of suicide; rather, their acts were, in his words, aimed "at moving the hearts of the oppressors, and at calling the attention of the world to the suffering endured then by the Vietnamese."[36][37][35][38]

The Order of Interbeing expanded into an international community of laypeople and monastics focused on "mindfulness practice, ethical behavior, and compassionate action in society."[39] By 2017, the group had grown to include thousands known to recite the Fourteen Precepts.[33]

During the Vietnam War

[edit]Vạn Hạnh University was taken over by one of the chancellors, who wished to sever ties with Nhất Hạnh and the SYSS, accusing Chân Không of being a communist. Thereafter the SYSS struggled to raise funds and faced attacks on its members. It persisted in its relief efforts without taking sides in the conflict.[10]

Nhất Hạnh returned to the U.S. in 1966 to lead a symposium in Vietnamese Buddhism at Cornell University and continue his work for peace.[13] He was invited by Professor George McTurnan Kahin, also of Cornell and a U.S. government foreign policy consultant, to participate on a forum on U.S. policy in Vietnam. On 1 June, Nhất Hạnh released a five-point proposal addressed to the U.S. government, recommending that (1) the U.S. make a clear statement of its desire to help the Vietnamese people form a government "truly responsive to Vietnamese aspirations"; (2) the U.S. and South Vietnam cease air strikes throughout Vietnam; (3) all anti-communist military operations be purely defensive; (4) the U.S. demonstrate a willingness to withdraw within a few months; and (5) the U.S. offer to pay for reconstruction.[13] In 1967 he wrote Vietnam — The Lotus in the Sea of Fire, about his proposals.[13] The South Vietnamese military junta responded by accusing him of treason and being a communist.[13]

While in the U.S., Nhất Hạnh visited Gethsemani Abbey to speak with the Trappist monk Thomas Merton.[40] When the South Vietnamese regime threatened to block Nhất Hạnh's reentry to the country, Merton wrote an essay of solidarity, "Nhat Hanh is my Brother".[40] Between June and October 1963, Nhất Hạnh conducted numerous interviews with newspapers and television networks to rally support for the peace movement.[41] During this time, he also undertook a widely publicized five-day fast. Additionally, he translated reports of human rights violations from Vietnamese into English and compiled them into a document he presented to the United Nations.[41] In 1964, after the publication of his poem "whoever is listening, be my witness: I cannot accept this war...", the American press called Nhất Hạnh an "antiwar poet" and a "pro-Communist propagandist".[2] In 1965 he wrote Martin Luther King Jr. a letter titled "In Search of the Enemy of Man".[42] During his 1966 stay in the U.S., Nhất Hạnh met King and urged him to publicly denounce the Vietnam War.[43] In 1967, due in large part to Nhất Hạnh,[44][45] King gave the speech "Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence" at Riverside Church in New York City, his first to publicly question U.S. involvement in Vietnam.[46] Later that year, King nominated Nhất Hạnh for the 1967 Nobel Peace Prize. In his nomination, King said, "I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of the Nobel Peace Prize than this gentle monk from Vietnam. His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity".[47] King also called Nhất Hạnh "an apostle of peace and nonviolence".[48] King named the candidate he had chosen to nominate with a "strong request" to the prize committee, in sharp violation of Nobel traditions and protocol.[49][50] The committee did not make an award that year.[2]

Refuge in France

[edit]Nhất Hạnh moved to Paris in 1966 and became the chair of the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation a group involved with the Paris Peace Accords, which ultimately ended American involvement in the Vietnam War.[14][51] For refusing to take sides in the war, Nhất Hạnh was exiled by both the North and South Vietnamese governments. He received asylum in France[51][52][53] and moved to the Paris suburbs, living with other Vietnamese refugees.[51]

In 1969, Nhất Hạnh established the Unified Buddhist Church (Église Bouddhique Unifiée) in France (not a part of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam). In 1975, he formed the Sweet Potatoes Meditation Centre at Fontvannes, in the Foret d’Othe, near Troyes in Aube province southeast of Paris.[13] For the next seven years, he focused on writing, and completed The Miracle of Mindfulness, The Moon Bamboo, and The Sun My Heart.[13]

Nhất Hạnh began teaching mindfulness in the mid-1970s with his books, particularly The Miracle of Mindfulness (1975), serving as the main vehicle for his early teachings.[54] In an interview for On Being, he said that The Miracle of Mindfulness was "written for our social workers, first, in Vietnam, because they were living in a situation where the danger of dying was there every day. So out of compassion, out of a willingness to help them to continue their work, The Miracle of Mindfulness was written as a manual practice. And after that, many friends in the West, they think that it is helpful for them, so we allow it to be translated into English."[55] The book was originally titled The Miracle of Being Awake, as in 1975 "mindfulness" was barely recognized in English.[51] Its focus on integrating mindfulness into daily life, rather than confining it to meditation, emphasized that living mindfully could foster personal growth, enlightenment, and even global peace.[51]

Campaign to help boat people and expulsion from Singapore

[edit]When the North Vietnamese army took control of the south in 1975, Nhất Hạnh was denied permission to return to Vietnam,[14] and the communist government banned his publications.[13] He soon began to lead efforts to help rescue Vietnamese boat people in the Gulf of Siam,[56] eventually stopping under pressure from the governments of Thailand and Singapore.[57]

Recounting his experience years later, Nhất Hạnh said he was in Singapore attending a conference on religion and peace when he discovered the plight of the suffering of the boat people:[20]

So many boat people were dying in the ocean, and Singapore had a very harsh policy on the boat people… The policy of Singapore at that time was to reject the boat people; Malaysia, also. They preferred to have the boat people die in the ocean rather than to bring them to land and make them into prisoners. Every time there was a boat with the boat people [that came] to the shore, they tried to push them [back] out into the sea in order [for them] to die. They didn't want to host [them]. And those fishermen who had compassion, who were able to save the boat people from drowning in the sea, were punished. They had to pay a very huge sum of money so that next time they won't have the courage to save the boat people.

He stayed on in Singapore to organise a secret rescue operation. Aided by concerned individuals from France, the Netherlands, and other European countries, he hired a boat to bring food, water and medicine to refugees in the sea. Sympathetic fishermen who had rescued boat people would call up his team, and they shuttled the refugees to the French embassy in the middle of the night and helped them climb into the compound, before they were discovered by staff in the morning and handed over to the police where they were placed in the relative safety of detention.[58][59] Please Call Me by My True Names, Nhất Hạnh's best-known poem, was written in 1978 during his efforts to assist the boat people.[60]

When the Singapore government discovered the clandestine network, the police surrounded its office and impounded the passports of both Nhất Hạnh and Chân Không, giving them 24 hours to leave the country. It was only with the intervention of the then-French ambassador to Singapore Jacques Gasseau that they were given 10 days to wind down their rescue operations.[61][62]

Nhất Hạnh was only allowed to return to Singapore in 2010 to lead a meditation retreat at the Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery.[citation needed]

Plum Village

[edit]By 1982, Sweet Potatoes was too small to accommodate the growing number of people who wanted to visit for retreats.[60] In 1982, Nhất Hạnh and Chân Không established the Plum Village Monastery, a vihara[A] in the Dordogne near Bordeaux in southern France.[8] Plum Village is the largest Buddhist monastery in Europe and America, with over 200 monastics and over 10,000 visitors a year.[63][64]

The Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism[65] (formerly the Unified Buddhist Church) and its sister organization in France, the Congrégation Bouddhique Zen Village des Pruniers, are the legally recognized governing bodies of Plum Village in France.[66][67]

Expanded practice centres

[edit]

By 2019, Nhất Hạnh had built a network of monasteries and retreat centres in several countries,[68] including France, the U.S., Australia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Hong Kong.[69][70] Additional practice centres and associated organizations Nhất Hạnh and the Order of Interbeing established in the US include Blue Cliff Monastery in Pine Bush, New York; the Community of Mindful Living in Berkeley, California; Parallax Press; Deer Park Monastery (Tu Viện Lộc Uyển), established in 2000[24] in Escondido, California; Magnolia Grove Monastery (Đạo Tràng Mộc Lan) in Batesville, Mississippi; and the European Institute of Applied Buddhism in Waldbröl, Germany.[71][72] (The Maple Forest Monastery (Tu Viện Rừng Phong) and Green Mountain Dharma Center (Ðạo Tràng Thanh Sơn) in Vermont closed in 2007 and moved to the Blue Cliff Monastery in Pine Bush.) The monasteries, open to the public during much of the year, provide ongoing retreats for laypeople, while the Order of Interbeing holds retreats for specific groups of laypeople, such as families, teenagers, military veterans, the entertainment industry, members of Congress, law enforcement officers and people of colour.[73][74][75]

According to the Thích Nhất Hạnh Foundation, the charitable organization that serves as the Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism's fundraising arm, as of 2017 the monastic order Nhất Hạnh established comprises over 750 monastics in 9 monasteries worldwide.[76]

Nhất Hạnh established two monasteries in Vietnam, at the original Từ Hiếu Temple near Huế and at Prajna Temple in the central highlands.[citation needed]

Writings

[edit]Nhất Hạnh has published over 130 books, including more than 100 in English, which as of January 2019 had sold over five million copies worldwide.[21][77] His books, which cover topics including spiritual guides and Buddhist texts, teachings on mindfulness, poetry, story collections, a biography of the Buddha, and scholarly essays on Zen practice,[24][7] have been translated into more than 40 languages as of January 2022.[78] In 1986 Nhất Hạnh founded Parallax Press, a nonprofit book publisher and part of the Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism.[79]

During his long exile, Nhất Hạnh's books were often smuggled into Vietnam, where they had been banned.[7]

Later activism

[edit]In 2014, major Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Anglican, Catholic and Orthodox Christian leaders met to sign a shared commitment against modern-day slavery; the declaration they signed called for the elimination of slavery and human trafficking by 2020. Nhất Hạnh was represented by Chân Không.[80]

Nhất Hạnh was known to refrain from consuming animal products as a means of nonviolence toward animals.[81][38]

Christiana Figueres has said that Nhất Hạnh helped her overcome a personal crisis and develop the deep listening and empathy required to facilitate the Paris Agreement on climate change.[82]

Relations with Vietnamese governments

[edit]Nhất Hạnh's relationship with the government of Vietnam varied over the years. He stayed away from politics, but did not support the South Vietnamese government's policies of Catholicization. He questioned American involvement, putting him at odds with the Saigon leadership,[43][46] which banned him from returning to South Vietnam while he was abroad in 1966.[5]

His relationship with the communist government ruling Vietnam was tense due to its anti-religious stance. The communist government viewed him with skepticism, distrusted his work with the overseas Vietnamese population, and restricted his praying requiem on several occasions.[83]

Return visits to Vietnam 2005–2007

[edit]In 2005, after lengthy negotiations, the Vietnamese government allowed Nhất Hạnh to return for a visit. He was also allowed to teach there, publish four of his books in Vietnamese, and travel the country with monastic and lay members of his Order, including a return to his root temple, Tu Hieu Temple in Huế.[5][84] Nhất Hạnh arrived on 12 January after 39 years in exile.[13] The trip was not without controversy. Thich Vien Dinh, writing on behalf of the banned Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBCV), called for Nhất Hạnh to make a statement against the Vietnamese government's poor record on religious freedom. Vien Dinh feared that the government would use the trip as propaganda, suggesting that religious freedom is improving there, while abuses continue.[85][86][87]

Despite the controversy, Nhất Hạnh returned to Vietnam in 2007, while the heads of the UBCV, Thich Huyen Quang and Thich Quang Do, remained under house arrest. The UBCV called his visit a betrayal, symbolizing his willingness to work with his co-religionists' oppressors. Võ Văn Ái, a UBCV spokesman, said, "I believe Thích Nhất Hạnh's trip is manipulated by the Hanoi government to hide its repression of the Unified Buddhist Church and create a false impression of religious freedom in Vietnam."[83] The Plum Village website listed three goals for his 2007 trip to Vietnam: to support new monastics in his Order; to organize and conduct "Great Chanting Ceremonies" intended to help heal remaining wounds from the Vietnam War; and to lead retreats for monastics and laypeople. The chanting ceremonies were originally called "Grand Requiem for Praying Equally for All to Untie the Knots of Unjust Suffering", but Vietnamese officials objected, calling it unacceptable for the government to "equally" pray for South Vietnamese and U.S. soldiers. Nhất Hạnh agreed to change the name to "Grand Requiem For Praying".[83] During the 2007 visit, Nhất Hạnh suggested ending government control of religion to President Nguyen Minh Triet.[88] A provincial police officer later spoke to a reporter about this incident, accusing Nhất Hạnh of breaking Vietnamese law. The officer said, "[Nhất Hạnh] should focus on Buddhism and keep out of politics."[89]

During the 2005 visit, Nhất Hạnh 's followers were invited by Abbot Duc Nghi, a member of the official Buddhist Sangha of Vietnam, to occupy Bat Nha monastery and continue their practice there.[89] Nhất Hạnh's followers say that during a sacred ceremony at Plum Village Monastery in 2006, Nghi received a transmission from Nhất Hạnh and agreed to let them occupy Bat Nha.[88] Nhất Hạnh's followers spent $1 million developing the monastery, building a meditation hall for 1,800 people.[89] The government support initially given to his supporters is now believed to have been a ploy to get Vietnam off the US State Department's Religious Freedom blacklist, improve chances of entry into the World Trade Organization, and increase foreign investment.[90] During this time, thousands of people came center to practice, and Nhất Hạnh ordained more than 500 monks and nuns at the monastery.[91]

In 2008, during an interview in Italian television, Nhất Hạnh made some statements regarding the Dalai Lama that his followers claim upset Chinese officials, who in turn put pressure on the Vietnamese government. The chairman of Vietnam's national Committee on Religious Affairs sent a letter that accused Nhat Hanh's organization of publishing false information about Vietnam on its website. It was written that the posted information misrepresented Vietnam's policies on religion and could undermine national unity. The chairman requested that Nhất Hạnh's followers leave Bat Nha. The letter also stated that Abbot Duc Nghi wanted them to leave.[89] "Duc Nghi is breaking a vow that he made to us... We have videotapes of him inviting us to turn the monastery into a place for worship in the Plum Village tradition, even after he dies — life after life. Nobody can go against that wish," said Brother Phap Kham.[88] In September and October 2009, a standoff developed, which ended when authorities cut the power, and followed up with police raids augmented by mobs assembled through gang contacts. The attackers used sticks and hammers to break in and dragged off hundreds of monks and nuns.[90][92] "Senior monks were dragged like animals out of their rooms, then left sitting in the rain until police dragged them to the taxis where ‘black society’ bad guys pushed them into cars," a villager said in a phone interview.[92] Two senior monks had their IDs taken and were put under house arrest without charges in their home towns.[92] Monastics responded with chanting, but continued to be persecuted by the government.[91]

Religious approach and influence

[edit]

Engaged Buddhism

[edit]Nhất Hạnh combined a variety of teachings of Early Buddhist schools, Mahayana, Zen, and ideas from Western psychology to teach mindfulness of breathing and the four foundations of mindfulness, offering a modern perspective[dubious – discuss] on meditation practice.[citation needed][93]

Nhất Hạnh has also been a leader in the Engaged Buddhism movement[1] (he is credited with coining the term[94]), promoting the individual's active role in creating change. He credited the 13th-century Vietnamese Emperor Trần Nhân Tông with originating the concept. Trần Nhân Tông abdicated his throne to become a monk and founded the Vietnamese Buddhist school of the Bamboo Forest tradition.[95] He also called it Applied Buddhism in later years to emphasize its practical nature.[96]

Mindfulness Trainings

[edit]Nhất Hạnh rephrased the five precepts for lay Buddhists, which were traditionally written in terms of refraining from negative activities, such as committing to taking positive action to prevent or minimize others' negative actions. For example, instead of merely refraining from stealing, Nhất Hạnh wrote, "prevent others from profiting from human suffering or the suffering of other species on Earth" by, for example, taking action against unfair practices or unsafe workplaces.[97]

According to Plum Village, Manifesto 2000, introduced by UNESCO, was largely inspired by their five mindfulness trainings.[98][99] In keeping with the northern tradition of Bodhisattva precepts, Nhất Hạnh wrote the fourteen mindfulness trainings for the Order of Interbeing based on the ten deeds.[100] He also updated the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya for Plum Village monastics while keeping its number of rules, 250 for monks and 348 for nuns.[101]

Interbeing

[edit]Nhất Hạnh developed the English term "interbeing" by combining the prefix "inter-" with the verb "to be" to denote the interconnection of all phenomena.[102] This was inspired by the Chinese word 相即 in Master Fa Zang's "Golden Lion Chapter",[103] a Huayan summary of the Avatamsaka Sutra. Some scholars believed it was a presentation of the Prajnaparamita, which "is often said to provide a philosophical foundation" for Zen.[104][105] Nhất Hạnh was also known for expressing deep teachings through simple phrases or parables. "The sun my heart", for instance, was an insight of meditation on the interdependence of all things. He used "no mud no lotus" to illustrate the interrelationship between awakening and afflictions, well-being and ill-being. "A cloud never dies", on the other hand, is a contemplation of phenomena beyond birth and death. To teach non-duality, he often told the story of his left and right hand. His meditation on aimlessness (apranihita) was told through the story of a river. The relationship between waves and water explained the Dharma Realm of Unobstructed Interpenetration of Truth and Phenomena.[106]

A new translation of the Heart Sutra

[edit]Nhất Hạnh completed new English and Vietnamese translations of the Heart Sutra in September 2014.[107] In a letter to his students,[107] he said he wrote these new translations because he thought that poor word choices in the original text had resulted in significant misunderstandings of these teachings for almost 2,000 years.[107]

Manifestation-Only Teaching

[edit]Continuing the Yogācāra and Dharmalaksana school, Nhất Hạnh composed the "fifty verses on the nature of consciousness". He preferred calling the teaching manifestation-only (vijnapti-matrata) rather than consciousness-only (vijnana-matrata) to avoid misintepretation into a kind of idealism.[108]

The Father of Mindfulness

[edit]Called "the Father of Mindfulness",[4] Nhất Hạnh has been credited as one of the main figures in bringing Buddhism to the West, and especially for making mindfulness well known in the West.[109] According to James Shaheen, the editor of the American Buddhist magazine Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, "In the West, he's an icon. I can't think of a Western Buddhist who does not know of Thich Nhất Hạnh."[5] His 1975 book The Miracle of Mindfulness was credited with helping to "lay the foundations" for the use of mindfulness in treating depression through "mindfulness-based cognitive therapy", influencing the work of University of Washington psychology professor Marsha M. Linehan, the originator of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT).[4] J. Mark G. Williams of Oxford University and the Oxford Mindfulness Centre has said, "What he was able to do was to communicate the essentials of Buddhist wisdom and make it accessible to people all over the world, and build that bridge between the modern world of psychological science and the modern healthcare system and these ancient wisdom practices – and then he continued to do that in his teaching."[4] One of Nhất Hạnh's students, Jon Kabat-Zinn, developed the mindfulness-based stress reduction course that is available at hospitals and medical centres across the world,[21] and as of 2015, around 80% of medical schools are reported to have offered mindfulness training.[110] As of 2019, it was reported that mindfulness as espoused by Nhất Hạnh[dubious – discuss] had become the theoretical underpinning of a $1.1 billion industry in the U.S. One survey determined that 35% of employers used mindfulness in practices in the workplace.[21]

Interfaith dialogue

[edit]Nhất Hạnh was known for his involvement in interfaith dialogue, which was not common when he began. He was noted for his friendships with Martin Luther King Jr. and Thomas Merton, and King wrote in his Nobel nomination for Nhất Hạnh, "His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity".[111] Merton wrote an essay for Jubilee in August 1966 titled "Nhất Hạnh Is My Brother", in which he said, "I have far more in common with Nhất Hạnh than I have with many Americans, and I do not hesitate to say it. It is vitally important that such bonds be admitted. They are the bonds of a new solidarity ... which is beginning to be evident on all five continents and which cuts across all political, religious and cultural lines to unite young men and women in every country in something that is more concrete than an ideal and more alive than a program."[111] The same year, Nhất Hạnh met with Pope Paul VI and the pair called on Catholics and Buddhists to help bring about world peace, especially relating to the conflict in Vietnam.[111] According to Buddhism scholar Sallie B. King, Nhất Hạnh was "extremely skilled at expressing their teachings in the language of a kind of universal spirituality rather than a specifically Buddhist terminology. The language of this universal spirituality is the same as the basic values that they see expressed in other religions as well".[112]

Final years

[edit]In November 2014, Nhất Hạnh experienced a severe brain hemorrhage and was hospitalized.[113][114] After months of rehabilitation, he was released from the stroke rehabilitation clinic at Bordeaux Segalen University. In July 2015, he flew to San Francisco to speed his recovery with an aggressive rehabilitation program at UCSF Medical Center.[115] He returned to France in January 2016.[116] After spending 2016 in France, Nhất Hạnh travelled to Thai Plum Village.[117] He continued to see both Eastern and Western specialists while in Thailand,[117] but was unable to verbally communicate for the remainder of his life.[117]

In November 2018, a press release from the Plum Village community confirmed that Nhất Hạnh, then 92, had returned to Vietnam a final time and would live at Từ Hiếu Temple for "his remaining days". In a meeting with senior disciples, he had "clearly communicated his wish to return to Vietnam using gestures, nodding and shaking his head in response to questions".[11] In January 2019, a representative of Plum Village, Sister True Dedication, wrote:

Thầy's health has been remarkably stable, and he is continuing to receive Eastern treatment and acupuncture. When there's a break in the rains, Thay comes outside to enjoy visiting the Root Temple's ponds and stupas, in his wheelchair, joined by his disciples. Many practitioners, lay and monastic, are coming to visit Tu Hieu, and there is a beautiful, light atmosphere of serenity and peace, as the community enjoys practicing together there in Thay's presence.[118]

While it was clear Nhất Hạnh could no longer speak, Vietnamese authorities assigned plainclothes police to monitor his activities at the temple.[119]

Death

[edit]

Nhất Hạnh died at his residence in Từ Hiếu Temple on 22 January 2022, at age 95, as a result of complications from his stroke seven years earlier.[2][12][78] His death was widely mourned by various Buddhist groups in and outside Vietnam. The Dalai Lama, South Korean President Moon Jae-in and the U.S. State Department also issued words of condolence.[120][121][122]

His five-day funeral,[78] which began on the day of his death, had a seven-day wake[123] that culminated with his cremation on 29 January. In a 2015 book, Nhất Hạnh described what he wanted for the disposition of his remains, in part to illustrate how he believes that he "continues" on in his teachings:

I have a disciple in Vietnam who wants to build a stupa for my ashes when I die. He and others want to put a plaque with the words, "Here lies my beloved teacher." I told them not to waste the temple land...I suggested that, if they still insist on building a stupa, they have the plaque say, I am not in here. But in case people don't get it, they could add a second plaque, I am not out there either. If still people don't understand, then you can write on the third and last plaque, I may be found in your way of breathing and walking.[124]

At the conclusion of the 49-day mourning period, Nhất Hạnh's ashes were portioned and scattered in Từ Hiếu Temple and temples associated with Plum Village.[125]

Bibliography

[edit]- Vietnam: Lotus in a sea of fire. New York, Hill and Wang. 1967.

- The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation, Beacon Press, 1975. ISBN 978-0807012321.

- Being Peace, Parallax Press, 1987. ISBN 0-938077-00-7.

- The Sun My Heart, Parallax Press, 1988. ISBN 0-938077-12-0

- The Moon Bamboo, Parallax Press, 1989. ISBN 0938077201.

- Our Appointment with Life: Sutra on Knowing the Better Way to Live Alone, Parallax Press, 1990. ISBN 1-935209-79-5.

- Breathe, You Are Alive: Sutra on the Full Awareness of Breathing, Parallax Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0938077381. Revised in 1996.

- Old Path White Clouds: Walking in the Footsteps of the Buddha, Parallax Press, 1991. ISBN 81-216-0675-6.

- Peace Is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life, Bantam reissue, 1992. ISBN 9780553351392.

- The Diamond That Cuts Through Illusion, Commentaries on the Prajnaparamita Diamond Sutra, Parallax Press, 1992. ISBN 0-938077-51-1.

- Hermitage Among the Clouds, Parallax Press, 1993. ISBN 0-938077-56-2.

- Call Me By My True Names: The Collected Poems of Thich Nhat Hanh, Parallax Press, 1993. ISBN 0938077619. Second edition published in 2022 ISBN 9781952692260.

- Love in Action: Writings on Nonviolent Social Change, Parallax Press, 1993. ISBN 9781952692079.

- Zen Keys: A Guide to Zen Practice, Harmony, 1994. ISBN 978-0-385-47561-7.

- Cultivating The Mind Of Love, Full Circle, 1996. ISBN 81-216-0676-4.

- Living Buddha, Living Christ, Riverhead Trade, 1997. ISBN 1-57322-568-1.

- The Heart Of Understanding: Commentaries on the Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra, Full Circle, 1997. ISBN 81-216-0703-5, ISBN 9781888375923 (2005 edition).

- Transformation and Healing: Sutra on the Four Establishments of Mindfulness, Full Circle, 1997. ISBN 81-216-0696-9.

- True Love: A Practice for Awakening the Heart, Shambhala Publications, 1997. ISBN 1-59030-404-7.

- Fragrant Palm Leaves: Journals, 1962–1966, Riverhead Trade, 1999. ISBN 1-57322-796-X.

- Going Home: Jesus and Buddha as Brothers, Riverhead Books, 1999. ISBN 1-57322-145-7.

- The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching, Broadway Books, 1999. ISBN 0-7679-0369-2.

- The Miracle of Mindfulness: A Manual on Meditation, Beacon Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8070-1239-4 (Vietnamese: Phép lạ của sự tỉnh thức).

- The Path of Emancipation: Talks from a 21-Day Mindfulness Retreat, Unified Buddhist Church, 2000. ISBN 81-7621-189-3.

- The Raft Is Not the Shore: Conversations Toward a Buddhist/Christian Awareness, Daniel Berrigan (Co-author), Orbis Books, 2000. ISBN 1-57075-344-X.

- A Pebble for Your Pocket, Full Circle Publishing, 2001. ISBN 81-7621-188-5.

- Thich Nhat Hanh: Essential Writings, Robert Ellsberg (Editor), Orbis Books, 2001. ISBN 1-57075-370-9.

- Anger: Wisdom for Cooling the Flames, Riverhead Trade, 2001. ISBN 1-57322-937-7.

- Be Free Where You Are, Parallax Press, 2002. ISBN 1-888375-23-X.

- My Master's Robe: Memories of a Novice Monk, Parallax Press, 2002. ISBN 978-1888375039.

- No Death, No Fear, Riverhead Trade reissue, 2003. ISBN 1-57322-333-6.

- Creating True Peace: Ending Violence in Yourself, Your Family, Your Community, and the World, Parallax Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0743245197.

- Touching the Earth: Intimate Conversations with the Buddha, Parallax Press, 2004. ISBN 1-888375-41-8.

- The Hermit and the Well, with Vo-Dinh Mai (Illustrator), Parallax Press, 2004. ISBN 978-1937006105.

- Teachings on Love, Full Circle Publishing, 2005. ISBN 81-7621-167-2.

- Understanding Our Mind, HarperCollins, 2006. ISBN 978-81-7223-796-7.

- The Energy of Prayer: How to Deepen Your Spiritual Practice, Parallax Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1888375558.

- Present Moment Wonderful Moment: Mindfulness Verses for Daily Living, Parallax Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1888375619.

- Buddha Mind, Buddha Body: Walking Toward Enlightenment, Parallax Press, 2007. ISBN 1-888375-75-2.

- Nothing To Do, Nowhere To Go: Waking Up To Who You Are, Parallax Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1888375725.

- The Art of Power, HarperOne, 2007. ISBN 0-06-124234-9.

- Good Citizens: Creating Enlightened Society, Parallax Press, 2008, ISBN 978-1935209898.

- Mindful Movements: Ten Exercises for Well-Being, Parallax Press, 2008, ISBN 978-1-888375-79-4.

- Under the Banyan Tree: Overcoming Fear and Sorrow, Full Circle Publishing, 2008. ISBN 81-7621-175-3.

- A Handful of Quiet: Happiness in Four Pebbles, Parallax Press, 2008. ISBN 9781937006211.

- The World We Have: A Buddhist Approach to Peace and Ecology, Parallax Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1888375886.

- The Blooming of a Lotus, Beacon Press, 2009. ISBN 9780807012383.

- Reconciliation: Healing the Inner Child, Parallax Press, 2010. ISBN 1-935209-64-7.

- Savor: Mindful Eating, Mindful Life. HarperOne. 2010. ISBN 978-0-06-169769-2.

- You Are Here: Discovering the Magic of the Present Moment, Shambhala Publications, 2010. ISBN 978-1590308387.

- Fidelity: How to Create a Loving Relationship That Lasts, Parallax Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1935209911.

- The Novice: A Story of True Love, HarperCollins, 2011. ISBN 978-0-06-200583-0.

- Your True Home: The Everyday Wisdom of Thich Nhat Hanh, Shambhala Publications, 2011. ISBN 978-1-59030-926-1.

- Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice, Parallax Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1937006075.

- Awakening of the Heart: Essential Buddhist Sutras and Commentaries, Parallax Press, 2012. ISBN 978-1937006112.

- Fear: Essential Wisdom for Getting Through the Storm, HarperOne, 2012. ISBN 978-1846043185.

- Love Letter to the Earth, Parallax Press, 2012. ISBN 978-1937006389.

- The Pocket Thich Nhat Hanh, Shambhala Pocket Classics, 2012. ISBN 978-1-59030-936-0.

- The Art of Communicating, HarperOne, 2013. ISBN 978-0-06-222467-5.

- Is nothing something?: Kids' questions and zen answers about life, death, family, friendship, and everything in between, Parallax Press 2014. ISBN 978-1-937006-65-5.

- No Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming Suffering, Parallax Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1937006853.

- How to Eat, Parallax Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1937006723.

- How to Love, Parallax Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1937006884.

- How to Sit, Parallax Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1937006587.

- How to Walk, Parallax Press, 2015. ISBN 978-1937006921.

- How to Relax, Parallax Press, 2015. ISBN 978-1941529089.

- Inside the Now: Meditations on Time, Parallax Press, 2015. ISBN 978-1937006792.

- Silence: The Power of Quiet in a World Full of Noise, HarperOne, 2015. ASIN: B014TAC7GQ.

- At Home in the World: Stories and Essential Teachings from a Monk's Life, with Jason Deantonis (Illustrator), Parallax Press, 2016. ISBN 1941529429.

- How to Fight, Parallax Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1941529867.

- The Art of Living: Peace and Freedom in the Here and Now, HarperOne, 2017. ISBN 978-0062434661.

- The Other Shore: A New Translation of the Heart Sutra with Commentaries, Palm Leaves Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1-941529-14-0.

- How to See, Parallax Press, 2018. ISBN 978-19-4676-433-1.

- How to Connect, Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddishm, Inc., 2020. ISBN 978-84-1121-050-8.

- Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, HarperCollins, 2021. ISBN 978-0-06-295479-4.

Awards and honours

[edit]Nobel laureate Martin Luther King Jr. nominated Nhất Hạnh for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967.[47] The prize was not awarded that year.[126] Nhất Hạnh was awarded the Courage of Conscience award in 1991.[127]

Nhất Hạnh received 2015's Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award.[128][129]

In November 2017, the Education University of Hong Kong conferred an honorary doctorate upon Nhất Hạnh for his "lifelong contributions to the promotion of mindfulness, peace and happiness across the world". As he was unable to attend the ceremony in Hong Kong, a simple ceremony was held on 29 August 2017, in Thailand, where John Lee Chi-kin, vice-president (academic) of EdUHK, presented the honorary degree certificate and academic gown to Nhất Hạnh on the university's behalf.[130][131]

In popular culture

[edit]Films

[edit]Nhất Hạnh has been featured in many films, including:

- The Power of Forgiveness, shown at the Dawn Breakers International Film Festival[132]

- Walk with Me, a documentary directed by Marc James Francis and Max Pugh, and supported by director Alejandro González Iñárritu.[133] Filmed over three years, Walk with Me focuses on the Plum Village monastics' daily life and rites, with Benedict Cumberbatch narrating passages from Fragrant Palm Leaves in voiceover.[134] The film was released in 2017, premiering at SXSW Festival.[133]

- One: The Movie: Nhất Hạnh and Chân Không appear in this documentary that surveys beliefs on the meaning of life.[135]

- A Cloud Never Dies: a biographical documentary produced by Pugh and Francis and narrated by Peter Coyote. Pugh, Max, Francis, Marc J. (2 April 2022). A Cloud Never Dies (documentary).

Graphic novel

[edit]Along with Alfred Hassler and Chân Không, Nhất Hạnh is the subject of the 2013 graphic novel The Secret of the 5 Powers.[136]

See also

[edit]- Buddhism in Vietnam

- Buddhist crisis

- Vietnamese Thiền

- List of peace activists

- Religion and peacebuilding

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Buddhist monastery and Zen center; a secluded retreat originally intended for wandering monks

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Carolan, Trevor (1 January 1996). "Mindfulness Bell: A Profile of Thich Nhat Hanh". Lion's Roar. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mydans, Seth (21 January 2022). "Thich Nhat Hanh, Monk, Zen Master and Activist, Dies at 95". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Gleig, Ann (28 June 2021). "Engaged Buddhism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.755. ISBN 9780199340378. Archived from the original on 7 July 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bryant, Miranda (22 January 2022). "From MLK to Silicon Valley, how the world fell for 'father of mindfulness'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson, Kay (16 January 2005). "A Long Journey Home". Time Asia (online version). Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Thich Nhat Hanh obituary". The Times. 25 January 2022. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Schudel, Matt (22 January 2022). "Thich Nhat Hanh, Buddhist monk who sought peace and mindfulness, dies at 95". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Religion & Ethics – Thich Nhat Hanh". BBC. 4 April 2006. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ Samar Farah (4 April 2002). "An advocate for peace starts with listening". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 11 June 2002. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ a b Nhu, Quan (2002). "Nhat Hanh's Peace Activities" in "Vietnamese Engaged Buddhism: The Struggle Movement of 1963–66"". Reprinted on the Giao Diem si. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2010. (2002)

- ^ a b "Thich Nhat Hanh Returns Home". Plum Village. 2 November 2018. Archived from the original on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ a b Joan Duncan Oliver (21 January 2022). "Thich Nhat Hanh, Vietnamese Zen Master, Dies at 95". Tricycle. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Taylor, Philip (2007). "The 2005 Pilgrimage and Return to Vietnam of Exiled Zen Master Thích Nhất Hạnh". Modernity and Re-enchantment: Religion in Post-revolutionary Vietnam. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 279–341. ISBN 9789812304407. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Miller, Andrea (30 September 2016) [1 July 2010]. "Peace in Every Step". Lion's Roar. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Thich Nhat Hanh: 20-page Biography". Plum Village. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh full biography". Plum Village. 22 January 2022. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d Dung, Thay Phap (2006). "A Letter to Friends about our Lineage" (PDF). PDF file on the Order of Interbeing website. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Geotravel Research Center, Kissimmee, Florida (1995). "Vietnamese Names". Excerpted from "Culture Briefing: Vietnam". Things Asian website. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Title attributed to TNH on the Vietnamese Plum Village site" (in Vietnamese). Langmai.org. 31 December 2011. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ a b Cordova, Nathaniel (2005). "The Tu Hieu Lineage of Thien (Zen) Buddhism". Blog entry on the Woodmore Village website. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d Fitzpatrick, Aidyn (24 January 2019). "The Father of Mindfulness Awaits the End of This Life". Time. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh: Extended Biography". Plum Village. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ "The Life of Thich Nhat Hanh". Lion’s Roar. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Greenblatt, Lilly (21 January 2022). "Remembering Thich Nhat Hanh (1926–2022)". Lion's Roar. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Armstrong, April C. (4 November 2020). "Dear Mr. Mudd: Did Thich Nhat Hanh Attend or Teach at Princeton University?". Mudd Manuscript Library Blog. Archived from the original on 4 November 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ Chan Khong (2005). Learning True Love: Practicing Buddhism in a Time of War. Parallax Press. ISBN 978-1427098429.

- ^ Mau, Thich Chi (1999) "Application for the publication of books and sutras", letter to the Vietnamese Governmental Committee of Religious Affairs, reprinted on the Plum Village website. He is the Elder of the Từ Hiếu branch of the 8th generation of the Liễu Quán lineage in the 42nd generation of the Linji school (臨 濟 禪, Vietnamese: Lâm Tế)

- ^ Schedneck, Brooke (24 January 2022). "Mindfulness in Life and Death". YES! Magazine. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Miller, Andrea (8 May 2017). "Path of Peace: The Life and Teachings of Sister Chan Khong". Lion's Roar. Shambhala Sun. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ "The Five Mindfulness Trainings". 28 December 2018. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ "The Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings of the Order of Interbeing". 28 December 2018. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ Sweas, Megan (29 April 2023). "After Thay". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ a b c Hanh, Thich Nhat; Eppsteiner, Fred (12 April 2017). "The Fourteen Precepts of Engaged Buddhism". Lion's Roar. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Topmiller, Robert J. (2005). "Struggling for Peace: South Vietnamese Buddhist Women and Resistance to the Vietnam War". Journal of Women's History. 17 (3): 133–157. doi:10.1353/jowh.2005.0037. ISSN 1527-2036. S2CID 144501009. Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ a b King, Sallie B. (2000). "They Who Burned Themselves for Peace: Quaker and Buddhist Self-Immolators during the Vietnam War". Buddhist-Christian Studies. 20: 127–150. doi:10.1353/bcs.2000.0016. ISSN 0882-0945. JSTOR 1390328. S2CID 171031594.

- ^ Archive Librarian (26 May 2015). "THICH NHAT HANH(1926– )from Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire: In Search of the Enemy of Man". The Ethics of Suicide Digital Archive. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

Although Giac Thanh was young at the time of his death, Quang Duc was over 70. Nhat Hanh had lived with the older monk for nearly a year at Long-Vinh pagoda before he set himself on fire, and describes him as "a very kind and lucid person . . . calm and in full possession of his mental faculties when he burned himself." Nhat Hanh insists that these acts of self-immolation are not suicide

- ^ "Why have some Buddhist monks set themselves on fire?". Tricycle: Buddhism for Beginners. 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ a b ""Oprah Talks to Thich Nhat Hanh" from "O, The Oprah Magazine"". March 2010. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ Zuisei Goddard, Vanessa (31 January 2022). "How Thích Nhất Hạnh changed the world beyond Buddhism". Religion News Service. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ a b Zahn, Max (30 September 2015). "Talking Buddha, Talking Christ". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Peace in Every Step". Lion’s Roar. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ "When Giants Meet". 11 January 2017. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2021. Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation.

- ^ a b "Searching for the Enemy of Man" in Nhat Nanh, Ho Huu Tuong, Tam Ich, Bui Giang, Pham Cong Thien". Dialogue. Saigon: La Boi. 1965. pp. 11–20. Archived from the original on 27 October 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2010., Archived on the African-American Involvement in the Vietnam War website

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh obituary | Mindfulness | The Guardian". web.archive.org. 27 March 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ Johnson/Hanoi, Kay (2 March 2007). "The Fighting Monks of Vietnam". TIME. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ a b Speech made by Martin Luther King, Jr. at the Riverside Church, NYC (4 April 1967). "Beyond Vietnam". Archived from the original on 10 May 2003. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b King, Martin Luther Jr. (25 January 1967). "Nomination of Thich Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize" (Letter). Archived on the Hartford Web Publishing website. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ Pearson, James (25 January 2022). "Thich Nhat Hanh, poetic peace activist and master of mindfulness, dies at 95". Reuters. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ "Facts on the Nobel Peace Prize". Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

The names of the nominees cannot be revealed until 50 years later, but the Nobel Peace Prize committee does reveal the number of nominees each year.

- ^ "Nomination Process". Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

The statutes of the Nobel Foundation restrict disclosure of information about the nominations, whether publicly or privately, for 50 years. The restriction concerns the nominees and nominators, as well as investigations and opinions related to the award of a prize.

- ^ a b c d e Zigmond, Dan (30 April 2022). "Why did Thay Come to the West? - Tricycle: The Buddhist Review". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review - The independent voice of Buddhism in the West. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ "The Life Story of Thich Nhat Hanh". Plum Village. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ Schedneck, Brooke (22 January 2022). "Thich Nhat Hanh, who worked for decades to teach mindfulness, approached death in that same spirit". The Conversation. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ Schedneck, Brooke (18 March 2019). "Thich Nhat Hanh, the Buddhist monk who introduced mindfulness to the West, prepares to die". The Conversation. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Tippett, Krista (27 January 2022) [25 September 2003; original air date]. "Remembering Thich Nhat Hanh, Brother Thay: 2003 Interview Transcript". The On Being Project. Transcribed by Heather Wang. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ Steinfels, Peter (19 September 1993). "At a Retreat, a Zen Monk Plants the Seeds of Peace". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh". Integrative Spirituality. Archived from the original on 22 May 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh believed that Buddhism should be a force for change". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ Team, Plum Village App (14 November 2020). "Helping refugees: Engaged Buddhism in action". Plum Village Mobile App. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ a b "Peace in Every Step". Lion’s Roar. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ Team, Plum Village App (14 November 2020). "Helping refugees: Engaged Buddhism in action". Plum Village Mobile App. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh obituary | Mindfulness | The Guardian". web.archive.org. 27 March 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ Knibbe, Guido (2020). "Meeting Life in Plum Village – Engaging With Precarity and Progress in a Meditation Center". Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology

- ^ "Plum Village". Plum Village. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ "Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism Inc. Web Site". Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ "The Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation". Plum Village. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ "Plum Village". Plum Village. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ Barclay, Eliza (11 March 2019). "Thich Nhat Hanh's final mindfulness lesson: How to die peacefully". Vox. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ Stanley, Steven; Purser, Ronald E.; Singh, Nirbhay N., eds. (2018). Handbook of Ethical Foundations of Mindfulness. Mindfulness in Behavioral Health. Springer. p. 345. ISBN 9783319765389.

- ^ "Plum Village Practice Centers". Plum Village. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ "Information about Practice Centers from the official Community of Mindful Living site". Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ^ webteam. "About the European Institute of Applied Buddhism". Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ "A Practice Center in the Tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh". deerparkmonastery.org. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- ^ "Article: Thich Nhat Hahn Leads Retreat for Members of Congress (2004) Faith and Politics Institute website". Faithandpolitics.org. 14 May 2013. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ Bures, Frank (25 September 2003). "Zen and the Art of Law Enforcement". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ "2016–2017 Annual Highlights from the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation". Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh". Plum Village. 11 January 2019. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ a b c "Thich Nhat Hanh: 'Father of mindfulness' Buddhist monk dies aged 95". BBC News. 22 January 2022. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "About – Parallax Press". www.parallax.org. 7 May 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ Belardelli, Guilia (2 December 2014). "Pope Francis And Other Religious Leaders Sign Declaration Against Modern Slavery". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Joan Halifax, Thích Nhất Hạnh (2004). "The Fruitful Darkness: A Journey Through Buddhist Practice and Tribal Wisdom". Grove Press. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

Being vegetarian here also means that we do not consume dairy and egg products, because they are products of the meat industry. If we stop consuming, they will stop producing.

[unreliable source?] - ^ "Being the Change We Want to See in the World: A Conversation with Christiana Figueres (Episode #21)". Plum Village. 17 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Kay (2 March 2007). "The Fighting Monks of Vietnam". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ Warth, Gary (2005). "Local Buddhist Monks Return to Vietnam as Part of Historic Trip". North County Times (re-published on the Buddhist Channel news website). Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ "Buddhist monk requests Thich Nhat Hanh to see true situation in Vietnam". Letter from Thich Vien Dinh as reported by the Buddhist Channel news website. Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, 2005. 2005. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ "Vietnam: International Religious Freedom Report". U.S. State Department: Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 8 November 2005. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Kenneth Roth; executive director (1995). "Vietnam: The Suppression of the Unified Buddhist Church". Vol.7, No.4. Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ a b c Ben, Stocking (22 September 2006). "Tensions rise as police question monk's followers". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 23 January 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d Stocking, Ben (1 August 2009). "Vietnam's Dispute With Zen Master Turns Violent". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 23 January 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ a b McCurry, Justin (2 October 2009). "Vietnamese riot police target Buddhist monk's followers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ a b "Peace in Every Step". Lion’s Roar. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ a b c Truc, Thanh (29 September 2009). "Monks Driven from Monastery". Radio Free Asia. Archived from the original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ Nhat Hanh, Thich (1975). The Miracle of Mindfulness; An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation (in Vietnamese). Translated by Ho, Mobi. Beacon Press 25 Beacon Street Boston, Massachusetts 02108-2892: Beacon Press. pp. vii–xiii. ISBN 0-8070-1239-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Duerr, Maia (26 March 2010). "An Introduction to Engaged Buddhism". PBS. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ Hunt-Perry, Patricia; Fine, Lyn (2000). "All Buddhism is Engaged: Thich Nhat Hanh and the Order of Interbeing". In Queen, Christopher S. (ed.). Engaged Buddhism in the West. Wisdom Publications. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0861711598.

- ^ "What Is "Applied Buddhism"? – The Mindfulness Bell". Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ King, pp. 26–27.

- ^ "Manifesto 2000: Creating a Culture of Peace and Nonviolence". Plum Village App. 10 March 2022. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023.

- ^ "Information kit on the Global Movement for The International Year for the Culture of Peace: peace is in our hands". UNESCO Digital Library.

- ^ Nhat Hanh, Thich (2020). Interbeing: The 14 Mindfulness Trainings of Engaged Buddhism. Parallax Press.

- ^ Nhat Hanh, Thich (2004). Freedom Wherever We Go: A Buddhist Monastic Code for the 21st Century (PDF). Parallax Press.

- ^ Nhat Hanh, Thich (1988). "Interbeing". The Heart of Understanding: Commentaries on the Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra (PDF). Parallax Press.

- ^ "Con sư tử vàng của thầy Pháp Tạng". Lang Mai.

- ^ McMahan, David L. (2008). The making of Buddhist modernism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-19-972029-3. OCLC 299382315. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Williams, Paul (2009). Mahāyāna Buddhism : the doctrinal foundations. Routledge. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-415-35652-7. OCLC 417575036. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Nhat Hanh, Thich. The Sun My Heart. Parallax Press.

- ^ a b c "New Heart Sutra translation by Thich Nhat Hanh". Plum Village Web Site. 13 September 2014. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Nhat Hanh, Thich. Transformation at the Base: 50 Verses on the Nature of Consciousness. Parallax Press. ISBN 9781888375145.

- ^ "Buddhist monk who brought mindfulness to West dies in Vietnam". France24. Agence France-Presse. 22 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Buchholz, Laura (October 2015). "Exploring the Promise of Mindfulness as Medicine". JAMA. 314 (13): 1327–1329. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.7023. PMID 26441167.

- ^ a b c Fox, Thomas C. (22 January 2021). "Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, teacher of mindfulness and nonviolence, dies at age 95". National Catholic Reporter. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ King, Sallie B. (2009). Socially Engaged Buddhism. Dimensions of Asian Spirituality. University of Hawaii Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-8248-3335-0.

- ^ "Our Beloved Teacher in Hospital". 12 November 2014. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh Hospitalized for Severe Brain Hemorrhage". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. 13 November 2014. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "An Update on Thay's Health: 14th July 2015". Plum Village Monastery. 14 July 2015. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ "An Update on Thay's Health: 8th January 2016". Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ a b c "On his 92nd birthday, a Thich Nhat Hanh post-stroke update". Lion's Roar. 10 October 2018. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ Littlefair, Sam (25 January 2019). "Thich Nhat Hanh's health 'remarkably stable', despite report in TIME". Lion's Roar. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "Thousands Mourn Passing Of Father Of Mindfulness". The ASEAN Post | Your Gateway To Southeast Asia's Economy. 29 December 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ "Condolences in Response to the Death of Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh". Office of the 14th Dalai Lama. 22 January 2022. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ PRice, Ned (23 January 2022). "On the Passing of Zen Master Thích Nhất Hạnh". US State Department. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ "Moon Offers Condolences over Death of Buddhist Monk Thich Nhat Hanh". Korean Broadcasting System. 23 January 2022. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Dinh, Hau (29 January 2022). "Funeral held in Vietnam for influential monk Thich Nhat Hanh". AP News. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Thich, Nhat Hanh (November 2016). At Home in the World: Stories & Essential Teachings from a Monk's Life. Parallax Press. ISBN 9781941529430.

- ^ "Ceremonies to Spread Thay's Ashes". Plum Village. 8 March 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ "Facts on the Nobel Peace Prize". Nobel Media. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ "The Peace Abbey – Courage of Conscience Recipients List". Archived from the original on 14 February 2009.

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh to receive Catholic "Peace on Earth" award". Lion's Roar. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ Diocese of Davenport (23 October 2015). "Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award recipient announced". Archived from the original on 16 March 2017.

- ^ "EdUHK to Confer Honorary Doctorates on Distinguished Individuals | Press Releases | The Education University of Hong Kong (EdUHK)". www.eduhk.hk. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- ^ "The Education University of Hong Kong". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ "First line up". Dawn Breakers International Film Festival (DBIFF). 5 December 2009. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ a b Barraclough, Leo (9 March 2017). "Alejandro G. Inarritu on Mindfulness Documentary 'Walk with Me' (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ Catsoulis, Jeannette (17 August 2017). "Review: 'Walk with Me,' an Invitation from Thich Nhat Hanh". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ "One: The Movie". IMDb. 20 April 2007.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Sperry, Rod Meade (May 2013), "3 Heroes, 5 Powers", Lion's Roar, vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 68–73

External links

[edit]- Order of Interbeing

- Parallax Press – founded by Thich Nhat Hanh

- Plum Village – Thich Nhat Hanh's monastery

- Sangha Directory – List of communities practicing in Thich Nhat Hanh's tradition

- 1926 births

- 2022 deaths

- 20th-century Buddhist monks

- 20th-century non-fiction writers

- 20th-century Vietnamese writers

- 20th-century Vietnamese poets

- 21st-century Buddhist monks

- 21st-century non-fiction writers

- 21st-century Vietnamese poets

- 21st-century Vietnamese writers

- Buddhism in France

- Buddhist pacifists

- Buddhist and Christian interfaith dialogue

- Buddhist writers

- Columbia University faculty

- Engaged Buddhism

- Engaged Buddhists

- Founders of new religious movements

- Mindfulness (Buddhism)

- Mindfulness movement

- Monks of Vietnamese descent

- Nautilus Book Award winners

- Nonviolence advocates

- People from Dordogne

- People from Huế

- Plum Village Tradition

- Princeton University alumni

- Rinzai Buddhists

- Thiền Buddhists

- Veganism activists

- Vietnamese Buddhist missionaries

- Vietnamese Buddhist monks

- Vietnamese emigrants to France

- Vietnamese pacifists

- Vietnamese people of the Vietnam War

- Vietnamese religious leaders

- Thiền Buddhist monks

- Zen Buddhist spiritual teachers