The Adventure of the Reigate Squire

| "The Adventure of the Reigate Squire" | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Short story by Arthur Conan Doyle | |||

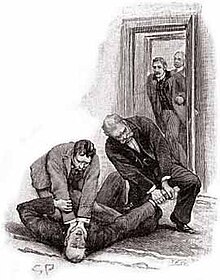

The Cunninghams fighting with Holmes, 1893 illustration by Sidney Paget in The Strand Magazine | |||

| Country | United Kingdom | ||

| Language | English | ||

| Genre(s) | Detective fiction short stories | ||

| Publication | |||

| Published in | Strand Magazine | ||

| Publication date | June 1893 | ||

| Chronology | |||

| Series | The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes | ||

| |||

"The Adventure of the Reigate Squire", also known as "The Adventure of the Reigate Squires" and "The Adventure of the Reigate Puzzle", is one of the 56 Sherlock Holmes short stories written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The story was first published in The Strand Magazine in the United Kingdom and Harper's Weekly in the United States in June 1893. It is one of 12 stories in the cycle collected as The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes.

Doyle ranked "The Adventure of the Reigate Squire" twelfth in his list of his twelve favorite Holmes stories.[1]

Plot

[edit]Watson takes Holmes to a friend's estate near Reigate in Surrey to rest after a rather strenuous case in France. Their host is Colonel Hayter. There has recently been a burglary at the nearby Acton estate in which the thieves stole a motley assortment of things, even a ball of twine, but nothing terribly valuable. Then one morning, the Colonel's butler tells news of a murder at another nearby estate, the Cunninghams'. The victim is William Kirwan, the coachman. Inspector Forrester has taken charge of the investigation, and there is one physical clue: a torn piece of paper found in William's hand with a few words written on it, including "quarter to twelve", which was approximately the time of William's murder. Holmes takes an instant interest in the note.

One of the first facts to emerge is that there is a longstanding legal dispute between the Actons and the Cunninghams involving ownership of about half of the estate currently in the Cunninghams' hands. Holmes interviews the two Cunningham men, young Alec and his ageing father. Alec tells Holmes that he saw the burglar struggling with William when a shot went off and William fell dead, and that the burglar ran off through a hedge to the road. The elder Cunningham claims that he was in his room smoking at the time, and Alec says that he had also still been up.

Holmes knows that it would be useful to get hold of the rest of that note found in William's hand. He believes that the murderer snatched it away from William and thrust it into his pocket, never realizing that a scrap of it was still in the murdered coachman's hand. Unfortunately, neither the police nor Holmes can get any information from William's mother, for she is quite old, deaf, and somewhat simple-minded.

Holmes, apparently still recovering from his previous strenuous case, seems to have a fit just as Forrester is about to mention the torn piece of paper to the Cunninghams. Afterward, Holmes remarks that it is extraordinary that a burglar would break into the Cunninghams' house when the Cunninghams were both still awake and had lamps lit. Holmes then apparently makes a mistake writing an advertisement that the elder Cunningham corrects.

Holmes insists on searching the Cunninghams' rooms despite their protests that the burglar could not have gone there. He sees Alec's room and then his father's, where he deliberately knocks a small table over, sending some oranges and a water carafe to the floor. The others were not looking his way at the time, and Holmes implies that the cause is Watson's clumsiness. Watson plays along and starts gathering up scattered oranges.

Everyone then notices that Holmes has left the room. Moments later, there are cries of "murder" and "help". Watson recognizes his friend's voice. He and Forrester rush to Alec's room where they find Alec trying to throttle Holmes and his father apparently twisting Holmes's wrist. The Cunninghams are quickly restrained, and Holmes tells Forrester to arrest the two for murdering William Kirwan. At first, Forrester thinks Holmes must be mad, but Holmes draws his attention to the looks on their faces – very guilty. After a revolver is knocked out of Alec's hand, the two are arrested. The gun is the one that was used to murder William, and it is seized.

Holmes has found the rest of the note, still in Alec's dressing gown pocket. It runs thus (the words in boldface are the ones on the original scrap):

- "If you will only come round at quarter to twelve

- to the east gate you will learn what

- will very much surprise you and maybe [sic]

- be of the greatest service to you and also

- to Annie Morrison. But say nothing to anyone

- upon the matter."

Holmes, an expert at studying handwriting, reveals that he had realized earlier from the torn piece of paper that the note was written by two men, each writing alternate words. He had perceived that one man was young, the other rather older, and that they were related, which led Holmes to conclude that the Cunninghams wrote the letter. Holmes saw that the Cunninghams' story was false since William's body has no powder burns on it, so he was not shot at point-blank range as the Cunninghams claim. The escape route also does not bear their story out: there is a boggy ditch next to the road that the fleeing murderer would have had to cross, yet there are no signs of any footprints in it. Holmes had faked his fit to prevent the Cunninghams from being reminded about and destroying the missing part of the note, and made a mistake in the advertisement on purpose to get the elder Cunningham to write the word "twelve" by hand, to compare it with the note fragment.

The elder Cunningham's confidence is broken after his arrest and he tells all. It seems that William followed his two employers the night they broke into the Acton estate (Holmes has already deduced that it was they, in pursuit of documents supporting Mr. Acton's legal claim, which they did not find). William then proceeded to blackmail his employers – not realizing that it was dangerous to do such a thing to Alec – and they thought to use the recent burglary scare as a plausible way of getting rid of him. With a bit more attention paid to detail, they might very well have evaded all suspicion.

Holmes and Watson

[edit]This is one of the rare stories that show a glimpse of Watson's dedication and his life before he met Holmes, as well as Holmes' trust in Watson. Colonel Hayter is a former patient who Watson treated in Afghanistan and has offered his house to Watson and Holmes. Watson admits in convincing Holmes, "A little diplomacy was needed," for Holmes resists anything that sounds like coddling or sentimentalism. Watson also glosses over the facts of Holmes' illness from overwork, implying redundancy because all of Europe was "ringing with his name."

Holmes' health has collapsed after straining himself to the limit, and his success in the case means nothing to him in the face of his depression. With his superhuman physical and mental achievement, he has a correspondingly drastic fit of nervous prostration and needs Watson's assistance. Holmes clearly has no problem with asking Watson for help when he needs it, for he sends a wire and Watson is at his side twenty-four hours later. At the onset of the mystery, Watson warns Holmes to rest, not to get started on a new problem. However, Watson knows and has revealed in other writings that inactivity is anathema to Holmes, and his caution comes off as weak. Holmes takes it all with humour, but the reader does not doubt his mind is eagerly upon the trail of the crime. At the conclusion, he tells Watson: "I think our quiet rest in the country has been a distinct success, and I shall certainly return much invigorated, to Baker Street to-morrow."[2]

Publication history

[edit]The story only bore the title "The Adventure of the Reigate Squire" when it was published in The Strand Magazine.[3] When it was collected into book form, it was called "The Reigate Squires", the name under which it is most often known.[4]

The story was published in the UK in The Strand Magazine in June 1893, and in the US in Harper's Weekly on 17 June 1893. It was also published in the US edition of the Strand in July 1893. It was published in Harper's Weekly as "The Reigate Puzzle".[5] The story was published with seven illustrations by Sidney Paget in The Strand Magazine,[6] and with two illustrations by W. H. Hyde in Harper's Weekly.[7] It was included in the short story collection The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes,[6] which was published in the UK in December 1893 and in the US in February 1894.[8]

Adaptations

[edit]Film and television

[edit]One of the short films in the 1912 Éclair film series was based on the story. The short film, titled The Reigate Squires, starred Georges Tréville as Sherlock Holmes.[9]

The story was adapted as a short film, also titled The Reigate Squires, in 1922 as part of the Stoll film series starring Eille Norwood as Holmes.[10]

"The Reigate Squires" was adapted for a 1951 TV episode of Sherlock Holmes starring Alan Wheatley as Holmes.[11]

Radio and audio dramas

[edit]Edith Meiser adapted the story as an episode of the American radio series The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes with Richard Gordon as Sherlock Holmes and Leigh Lovell as Dr. Watson. The episode, titled "The Reigate Puzzle", aired on 29 December 1930.[12] Another episode adapted from the story aired on 29 February 1936, under the title "The Adventure of the Reigate Puzzle" (with Gordon as Holmes and Harry West as Watson).[13]

Meiser also adapted the story as an episode of the radio series The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes with Basil Rathbone as Holmes and Nigel Bruce as Watson. The episode, titled "The Reigate Puzzle", aired on 26 February 1940.[14]

A 1961 BBC Light Programme radio adaptation, titled "The Reigate Squires", was adapted by Michael Hardwick as part of the 1952–1969 radio series starring Carleton Hobbs as Holmes and Norman Shelley as Watson.[15]

An adaptation titled "The Reigate Squires" aired on BBC radio in 1978, starring Barry Foster as Holmes and David Buck as Watson.[16]

The story was adapted as an episode of CBS Radio Mystery Theater titled "The Reigate Mystery". The episode, which starred Gordon Gould as Sherlock Holmes and William Griffis as Dr. Watson, first aired in November 1982.[17]

"The Reigate Squires" was dramatised for BBC Radio 4 in 1992 by Robert Forrest, as part of the 1989–1998 radio series starring Clive Merrison as Holmes and Michael Williams as Watson. It featured Peter Davison as Inspector Forrester, Roger Hammond as Mr Cunningham, Struan Rodger as Alec Cunningham, and Terence Edmond as Mr Acton.[18]

A 2015 episode of The Classic Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, a series on the American radio show Imagination Theatre, was adapted from the story, with John Patrick Lowrie as Holmes and Lawrence Albert as Watson. The episode is titled "The Reigate Squires".[19]

In 2024, the podcast Sherlock&Co adapted the story in a two-episodes adventure called "The Reigate Squire", starring Paul Waggot as Watson and Harry Attwell as Sherlock.

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Temple, Emily (22 May 2018). "The 12 Best Sherlock Holmes Stories, According to Arthur Conan Doyle". Literary Hub. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Direct Quote from The Reigate Squires

- ^ "The Strand Magazine. v.5 1893 Jan–Jun". HathiTrust Digital Library. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "Discovering Sherlock Holmes – A Community Reading Project From Stanford University". sherlockholmes.stanford.edu. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Smith (2014), p. 87.

- ^ a b Cawthorne (2011), p. 85.

- ^ "Harper's Weekly. v.37 June–Dec.1893". HathiTrust Digital Library. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Cawthorne (2011), p. 75.

- ^ Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. p. 130. ISBN 9780060156206.

- ^ Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. p. 131. ISBN 9780060156206.

- ^ Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. p. 136. ISBN 9780060156206.

- ^ Dickerson (2019), p. 26.

- ^ Dickerson (2019), p. 73.

- ^ Dickerson (2019), p. 90.

- ^ De Waal, Ronald Burt (1974). The World Bibliography of Sherlock Holmes. Bramhall House. p. 388. ISBN 0-517-217597.

- ^ Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. p. 140. ISBN 9780060156206.

- ^ Payton, Gordon; Grams, Martin Jr. (2015) [1999]. The CBS Radio Mystery Theater: An Episode Guide and Handbook to Nine Years of Broadcasting, 1974–1982 (Reprinted ed.). McFarland. p. 432. ISBN 9780786492282.

- ^ Bert Coules. "The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes". The BBC complete audio Sherlock Holmes. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Wright, Stewart (30 April 2019). "The Classic Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: Broadcast Log" (PDF). Old-Time Radio. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Sources

- Cawthorne, Nigel (2011). A Brief History of Sherlock Holmes. Running Press. ISBN 978-0762444083.

- Dickerson, Ian (2019). Sherlock Holmes and His Adventures on American Radio. BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1629335087.

- Smith, Daniel (2014) [2009]. The Sherlock Holmes Companion: An Elementary Guide (Updated ed.). Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-78131-404-3.

External links

[edit] The full text of The Reigate Puzzle at Wikisource

The full text of The Reigate Puzzle at Wikisource Media related to The Adventure of the Reigate Squire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Adventure of the Reigate Squire at Wikimedia Commons- The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, including The Adventure of the Reigate Squire at Standard Ebooks

- Davies, Ross E. (23 November 2016). "Arthur Conan Doyle's the Reigate Puzzle: A Cartographical and Photographical View (Part 1) (map)". SSRN 2875061.

- Davies, Ross E. (23 November 2016). "Arthur Conan Doyle's the Reigate Puzzle: A Cartographical and Photographical View (Part 2) (map)". SSRN 2875062.