Thomas Grey (constable)

Sir Thomas Grey of Heaton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Died | before March 1344 |

| Allegiance | England |

| Service | Army |

| Rank | Knight Banneret |

| Commands | Warden of Cupar Castle Keeper of Norham Castle Deputy Constable of Berwick-upon-Tweed Keeper of Mitford Castle |

| Battles / wars | Action at Lanark (1297) Siege of Stirling Castle (1304) Ambush at Cupar Castle (1308) Battle of Bannockburn (1314) Capture of Berwick (1318) Siege of Norham (1322) Invasion of England (1326) |

| Spouse(s) | Agnes de Bayles |

| Relations | Thomas Grey (chronicler) |

Sir Thomas Grey (d. before March 1344) of Heaton Castle in the parish of Cornhill-on-Tweed, Northumberland, was a soldier who served throughout the wars of Scottish Independence. His experiences were recorded by his son Thomas Grey in his chronicles, and provide a rare picture of the day-to-day realities of the wars.

His career, blemished by his suicidal charge at the Battle of Bannockburn, a contributing factor to the devastating English defeat, is perhaps best known for his role in the tale of Sir William Marmion, the chivalric knight of Norham Castle.

Career and life

[edit]Early life

[edit]Grey was serving under William de Hesilrig, Sheriff of Clydesdale as early as 1297.[4] Following William Wallace's nighttime assassination of the Sheriff at Lanark, Grey was left for dead, stripped naked in the snow.[4] He only survived because of the heat from the houses burning around him and was rescued the next day and his wounds healed.[4]

Grey was knighted before September 1301 and served with the king's lieutenant for Scotland, Patrick IV, Earl of March at Ayr.[5][non-primary source needed]

In May 1303 Grey found himself under the command of Hugh Audley encamped at Melrose Abbey when they were attacked at night by a much larger force led by John Comyn.[6] Grey was beaten to the floor and taken prisoner but most of his comrades were slain.[7]

Siege of Stirling Castle (1304)

[edit]

Edward I had captured most of Scotland by April 1304 and embarked upon a nineteen-week siege of the last significant uncaptured fortress at Stirling Castle using twelve siege engines which included the massive trebuchet called "Warwolf".

Grey fought at the siege under the command of Henry de Beaumont.[8] A hook thrown from a siege machine ensnared de Beaumont one day, and was about to haul him to his death upon the castle walls, when Grey freed him in the nick of time and dragged him to safety.[8]

Just as Grey had performed this act of bravery he was struck in the head by a large bolt fired from a springald (a large multi-man crossbow) just below his eyes.[7] He collapsed to the ground lifeless and preparations for a quick burial were made.[8] Just as the funeral ceremony started, Grey suddenly stirred and opened his eyes, much to the astonishment of the funeral party.[8] He subsequently staged a full recovery.[8]

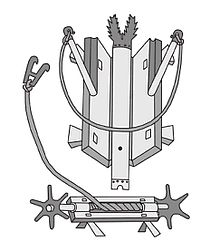

It is from this event that Grey perhaps adopted a ram's head as the crest of his coat of arms as a light-hearted reference to his thick skull.[3]

Grey became closer to the Beaumont family, who were kinsmen of both the king and queen, and was drawn into court life. In 1305 Grey acted as attorney for de Beaumont's sister Isabella de Vesci.[5][non-primary source needed] In December 1307 Grey took custody of Robert Bruce's sister Christina following the execution of her husband Christopher Seton for his part in the murder of John Comyn, Guardian of Scotland.[9][non-primary source needed]

Ambush at Cupar Castle (1308)

[edit]Upon the death of Edward I he was succeeded by his son Edward II and Grey attended the coronation at Westminster Palace in February 1308.[10] As Grey returned to Cupar Castle, of which he was the then warden, he was ambushed by Walter de Bickerton, a supporter of Bruce.[10]

Grey was heavily outnumbered, having only 26 man-at-arms compared to the 400 men commanded by Bickerton.[10] Deciding that he could not avoid the ambush he decided to charge the heart of Bickerton's men using lance and the shock of his horse to down many of the enemy.[10] Seeing the success of his aggression he was joined by his men at arms and together they succeeded in overthrowing many of the enemy and stampeded their horses.[11]

Before starting the charge, Grey had instructed his grooms to follow at a distance carrying a battle standard.[10] As they came into view of Bickerton's confused men they mistook the grooms for another formation of soldiers and took flight.[11] Grey and his men drove one hundred and eighty of Bickerton's abandoned horses to his castle as booty.[11]

Battle of Bannockburn (1314)

[edit]Grey's capture at the Battle of Bannockburn was undoubtedly the low point of his career. Grey served under Beaumont and Robert Clifford when they tried to go around the Scottish army on the first day of the battle and met with defeat at the hands of the forces of Sir Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray.[12]

On the second day of the battle, the English were heavily defeated and the king fled the field with a force of some 500 knights and was pursued by Sir James Douglas with only a small force, leaving hundreds of English dead on the field and a large number of English nobles and knights taken prisoner.[13]

Norham Castle

[edit]

Following their victory at Bannockburn, the Scottish attacked and raided the north of England repeatedly over the ensuing years. Grey was garrisoned at Berwick-upon-Tweed in 1318 which fell to Bruce following an eleven-week siege. Grey was subsequently recompensed £179 arrears of wages for himself and 14 man-at-arms and for horses he had lost.[14]

In 1317 Grey's patron de Beaumont and his brother Louis de Beaumont, soon to be installed as Bishop of Durham, were kidnapped by Guy de Middleton before being freed by William de Felton. Middleton was executed and his lands confiscated. In May 1319, as reward for his services, Grey was granted 108 acres at Howick, Northumberland that formerly belonged to a supporter of Middleton, John Mautulent.[15][non-primary source needed]

Grey was appointed in 1319 as Sheriff of Norham and Islandshire and Constable of Norham Castle[16] where he was to be based for 11 years.[17] During this time Norham remained under a state of almost perpetual siege and it is Grey's rescue of William Marmion that he is probably best known for.[18]

A two-year truce expired in 1322 and Grey promised the king to recruit an extra 20 men at arms and 50 hobelars to reinforce Lewis de Beaumont's existing garrison to protect both Norham castle and the March. By 17 September Norham found itself besieged by 100 Scottish men at arms and 100 hobelars. The king sent Grey money to pay his garrison and requested that he send frequent reports of the situation and reassured the people around the castle that any losses in crops and goods would be made up to them.[9][non-primary source needed]

Edward II agreed to a 13-year truce with Bruce in May 1323 and, three months later, Grey was given permission to go to Scotland to resupply Norham Castle with corn and ammunition and to replace its ploughs and carts which had been destroyed in the preceding years.[15][non-primary source needed] He imprisoned 80 Scots at Norham who had, coming from overseas, landed at Lindisfarne and attempted to reach Scotland and on 2 October was ordered to send them to the Sheriff of York at York Castle.[19][non-primary source needed]

On 9 July 1325 Grey was ordered to accept back into the king's peace all those of Northumberland who had joined the Scottish through poverty or other urgent needs.[15][non-primary source needed]

Later career

[edit]During the buildup to the impending Invasion of England of 1326 Grey was first granted more land at Howyk[15][9][non-primary source needed] and then in August ordered to join John de Sturmy, Admiral of the Fleet of the North, alongside other captains and their ships, to help defend the hugely unpopular Edward II from his wife Isabella and her lover Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March.[15][non-primary source needed] Grey was ordered to "compel" ships from Northumberland ports to join the fleet and to supervise their departure for Orwell, Suffolk in early September.[20][non-primary source needed] No naval conflict occurred and, landing at Orwell on 24 September, Isabella and Mortimer seized control of England with virtually no opposition, with most of Edward's orders having been ignored. Edward II was imprisoned and replaced on the throne by Edward III.

Edward III resumed hostilities with the Scottish and, shortly after the defeat of the Scottish at Halidon Hill in July 1333, Grey was appointed as deputy constable of Berwick.[21]

In about 1334 Grey was granted Mitford Castle and the hamlet of Mollisdoun[22] and in October 1335 he was granted custody of the lands and marriage of the heir of Andrew de Grey in Berwick.[15][non-primary source needed]

Family and descendants

[edit]Grey married Agnes de Bayles and had the following issue:

- Sir Thomas Grey, Soldier and Chronicler

- Margaret Grey (d. 27 May 1378), married John Eure de Aton

Thomas is an ancestor of the Earl Greys of Tankerville, Baronet Grey of Chillingham, Baron Greys of Powis and Baron Greys of Werke.

References

[edit]- ^ Burke 1884, p. 660

- ^ Foster 1902, p. 100

- ^ a b Bateson 1895

- ^ a b c Maxwell 1907, p. 18

- ^ a b Cal Docs Rel Scotland II 1884.

- ^ Maxwell 1907, p. 24

- ^ a b Maxwell 1907, p. 25

- ^ a b c d e Maxwell 1907, p. 26

- ^ a b c Cal Docs Rel Scotland III 1887.

- ^ a b c d e Maxwell 1907, p. 48

- ^ a b c Maxwell 1907, p. 49

- ^ Barbour, John (1997). The Brus. Cannongate Classics. p. 476.

- ^ Barrow, Geoffrey W.S. (1988). Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland. Edinburgh University Press. p. 231.

- ^ Moor 1929

- ^ a b c d e f Patent Rolls 1232–1509.

- ^ King 2005

- ^ Maxwell 1907, p. 61

- ^ Maxwell 1907, p. 61–63

- ^ Close Rolls 1224–1468.

- ^ Parl Writs II Digest 1834.

- ^ Maxwell 1913, p. 282

- ^ Cal Inq PMs VII.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bateson, Edward (1895). A History of Northumberland. Vol. II. Newcastle: Andrew Reid & Co Ltd.

- Burke, Bernard (1884). Burkes General Armoury. London: Burkes.

- Dodds, Margaret (1935). A History of Northumberland. Vol. XIV. Newcastle: Andrew Reid & Co Ltd.

- Foster, Joseph (1902). Some Feudal Coats of Arms. London: J.Parker & Co.

- Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem. Vol. VII. London: HMSO. 1909.

- King, Andy (2005). Sir Thomas Gray's Scalacronica, 1272–1363. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press.

- Maxwell, Herbert (1907). Scalacronica; The reigns of Edward I, Edward II and Edward III as Recorded by Sir Thomas Gray. Glasgow: James Maclehose & Sons. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- Maxwell, Herbert (1913). The Lanercost Chronicle. Glasgow: James Maclehose & Sons.

- Moor, Charles (1929). The Knights of Edward I. London: Harleian Society.

- Close Rolls. Westminster: Parliament of England. 1224–1468.

- Fine Rolls. Westminster: Parliament of England. 1199–1461.

- Patent Rolls. Westminster: Parliament of England. 1232–1509.

- Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Vol. II. Edinburgh: Public Record Office. 1884.

- Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Vol. III. Edinburgh: Public Record Office. 1887.

- Parliamentary Writs Alphabetical Digest. Vol. II. London: Public Record Office. 1834.

- Rogers, Clifford (2007). Soldiers Lives through History: the Middle Ages. London: Greenwood Press.

- Scott, Ronald McNair (1982). Robert the Bruce King of Scots. London: Hutchinson & Co.