Sealed crustless sandwich

A sealed crustless sandwich with peanut butter and jelly filling (mass-produced) | |

| Type | Sandwich |

|---|---|

| Course | Lunch, Snack |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Main ingredients | Bread, various fillings |

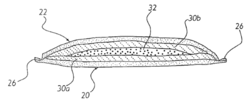

A sealed crustless sandwich consists of a filling between two layers of crimp-sealed bread, with the crust removed.

Homemade variations are typically square, round, or triangular; the bread can vary, e.g., white or whole wheat; and the sandwiches can be homemade with common crimping techniques similar to pie crust, ravioli, or dumplings using readily available kitchen tools (e.g., a fork, small spoon or curved knife end to crimp the edges). A purpose-designed "cut and crimp" tool can also be used.[1]

Mass-produced varieties vary in shape, are typically individually wrapped, frozen and packaged — and include proprietary brands as well as house brands. They were introduced in 1995 with peanut butter and jelly filling, followed by numerous patent[2] and trademark disputes as well as numerous competitors entering the market.

The sandwiches offer easily-frozen and thawed, ready-to-eat, portable convenience and have been called, "the Swiss Army knife of foods".[3]

Audience

Originally developed for as a prepared food for school lunches,[4] they have appeal across generations and can easily be included in a homemade lunch. In 2018, sealed crustless sandwiches were made available to firemen during the California wildfires.[5][6] National Football League teams buy tens of thousands of them for players to eat as snacks.[4]

Mass production

In the United States, mass-produced crustless sealed sandwiches were introduced in 1995, in Fargo, North Dakota by David Geske and Len Kretchman[7] — at the time marketing as Incredible Uncrustables to schools in the Midwest, with fifty employees making roughly 35,000 of the sealed sandwiches daily by 1998.[7] Their company was purchased by The J.M. Smucker Company in 1998.[7] In Japan, Yamazaki Baking has marketed Lunch Pack sealed sandwiches since 1984.

Companies have marketed sealed crustless sandwiches in square, triangular, round and even cloud shapes — with an extensive range of fillings, including ham,[8] cheese,[8] chocolate-hazelnut spread,[8] almond butter and jam,[9] peanut butter and honey,[8] peanut butter and apple butter, peanut butter and banana, sunflower butter and jelly — or, prominently, peanut butter and jelly.[8] In the case of the latter, some companies apply the peanut butter to both interior surfaces of the bread, shielding the bread from the jelly — engineer the bread to prevent filling leaks[10] or augment the crimping with starch to provide a tighter seal.

Mass-produced U.S. brands include:

- Chubby Snacks

- Crustless Cocoa CPB Sandwich by E-S Frozen Foods

- EZ Jammers by Albie's Foods

- Gallant Tiger

- Good & Gather Sunbutter and Jelly Sandwiches by Target

- Jammies by Sunbutter

- Lunch Buddies PB Delights by Aldi, Canadian made

- Luv Me Foods Organic Peanut Butter & Strawberry Jelly Sandwich

- Market Pantry Crustless Sandwiches by Target

- PB Jamwiches and PB Jamz by AdvancePierre Foods

- Pea B&J Pockets by Annie's

- PB&J sandwiches by Sam's Club and Welch's

- Wowbutter & Grape Jelly, Crustless Sandwiches, by Nature's Promise

- No Crust Sandwiches, by Walmart, Canadian made

- PB + J Crustless Sandwiches and Charlotte's Crustoffs, by Costco

- Sunwise sunflower butter and jelly sandwiches by Muffintown

- Uncrustables, by Smucker's

- Whistlin Sams by Tyson Foods

Smuckers has plants in Kentucky[11] Colorado[12] and Alabama[13] with Uncrustables sales projected at $500 million in 2021 — offering numerous variations, e.g., Grilled Cheese Uncrustable (approximately 2003-2014), Ham and Cheddar Bites, Pepperoni Bites and others. In 2023, Smucker said it took about ten years to prevent "leaky sandwiches," designing the bread so it doesn't create air pockets and using round loaves.[10]

Chubby Snacks, headquartered in Colorado,[14] launched as a direct-to-consumer brand in 2020. It markets its sealed sandwiches in a "cloud" shape[15] using organic, whole wheat bread; medjool dates and monk fruit for sweetness rather than refined sugar, and having 2-3 grams of sugar per sandwich.[16] The company aimed to manufacture 30 million sealed crustless sandwiches annually by 2024.[17]

Trademark infringement

Smuckers, with $7.8 billion in net sales as of 2020, has issued cease and desist letters to any company marketing crustless sealed sandwiches in a round shape, including small businesses, arguing trademark infringement. Targeted companies have included Chubby Snacks,[7] which revised their sandwiches to a cloud shape; Albie's Foods[7] which revised their EZ Jammers to a triangular and later square shape, and Gallant Tiger[18] which markets a decidedly adult-flavored product (e.g., chai spiced pear butter and peanut butter) selling at a price-point roughly six times the cost of an Uncrustable.

The Gallant Tiger founder noted that at a time when the company had seven sales outlets, "1,000 followers on Instagram and $20,000 in sales, and [Smuckers was] telling us that not only are we infringing on their trademark, which is a circle-shaped sandwich, but we also were falsifying advertising and essentially slandering them. It was weird. It was almost like in the eyes of Smucker, [Gallant Tiger] was a criminal," adding that a consumer "can tell the difference between Domino's and Pizza Hut [pizza] even though they're both circular food products. So what are we really talking about here?"[18]

Patent history

The United States Patent and Trademark Office issued a number of patents for mass-produced versions of a sealed crustless sandwich, which were subsequently reexamined and cancelled for having attempted to patent obvious or well known concepts.

The first claim of Menusaver's patent reads:

- A sealed crustless sandwich, comprising:

- a first bread layer having a first perimeter surface coplanar to a contact surface;

- at least one filling of an edible food juxtaposed to said contact surface;

- a second bread layer juxtaposed to said at least one filling opposite of said first bread layer, wherein said second bread layer includes a second perimeter surface similar to said first perimeter surface;

- a crimped edge directly between said first perimeter surface and said second perimeter surface for sealing said filling(s) between said first bread layer and said second bread layer;

- wherein a crust portion of said first bread layer and said second bread layer has been removed.

That is, the patent described a sandwich with a layer of filling in between two pieces of bread which are crimped shut and have their crust removed. The other nine claims of the patent elaborate the idea further, including the coating of two sides of the bread with peanut butter first before putting the jelly in the middle, so that the jelly would not seep into the bread—the layers of filling "are engaged to one another to form a reservoir for retaining the second filling in between".

Many intellectual property experts and members of the general public view this patent as an example of the patent office's inability to properly examine patent applications.[19] The patent examiner cited only seven previous patents issued between 1963 and 1998, and a 1994 book called 50 Great Sandwiches that were deemed relevant to the novelty and nonobviousness of the invention. He concluded that the invention was indeed novel and not obvious and allowed the claims.[19]

After the patent was issued, many more earlier patents and publications were found that teach some or all of the different aspects of the invention. These included a 1949 patent (U.S. patent 2,463,439) that described a device to create these types of sandwiches: "An object of this invention is to provide... a means for locating said filling in the center of the sandwich and sealing the marginal edges of the pieces by heat and pressure to preclude the escape of filling from the finished product... [and] a means for trimming the baked dough pieces". These new pieces of prior art were brought to the attention of the patent office through a reexamination proceeding.

The J.M. Smucker Co. also attempted to patent the process of making the sandwich in 2004 (rather than just the sandwich itself) and on April 8, 2005, had its application rejected by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC).[1].

Patent enforcement

In 2001, a small grocery and caterer in Gaylord, Michigan, Albie's Food, Inc., was sent a cease and desist letter from The J.M. Smucker Co., accusing Albie's of violating their intellectual property rights to the "sealed crustless sandwich". Instead of capitulating, Albie's took the case to federal court, noting in their filings a pocket sandwich with crimped edges and no crust was called a "pasty" and had been a popular dish in northern Michigan since the nineteenth century. Federal Court determined that Albie's Foods did not infringe on J.M. Smucker Co. intellectual property rights and was allowed to continue.[20]

Patent reexamination

In March 2001, during the legal proceedings, Albie's filed a request for reexamination with the USPTO asking that the patent be reexamined in light of the newly discovered prior art. The reexamination serial number is 90/005,949.

In response to the new prior art cited, Smucker's narrowed the wording of their claims to only cover a very specific version of their sealed crustless sandwich. The more narrow claims, for example, only cover sealed crustless peanut butter and jelly sandwiches where the jelly is held between two layers of peanut butter. Nonetheless, in December 2003, the patent examiner rejected the narrowed claims in light of the new prior art.

Smucker's appealed the rejection to the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences. In September 2006, the Board reversed the examiner's reasons for rejecting the claims, but found new reasons for rejecting them. They found that the wording in the narrowed claims was too vague to clearly identify exactly what Smucker's is trying to patent. Because Smucker's failed to respond to the Board's rejections within the two-month deadline, the PTO mailed a Notice of Intent to Issue a Reexamination Certificate (NIIRC) in December 2006 cancelling all claims. The reexamination certificate was issued on September 25, 2007.

See also

Notes

- ^ Reg Wydeven (August 6, 2005). "Smucker's in a bit of legal jam with uncrusted tradition". The Post-Crescent.

- ^ Kat Eschner (November 3, 2017). "Can a Sandwich Be Intellectual Property?". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ Joseph Lamour (December 2, 2004). "Smucker's is in a trademark fight with small business over round, crustless sandwiches". Today. Archived from the original on July 14, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ a b "Wait, NFL players eat how many Uncrustables?".

- ^ Chapple-Sokol, Sam (August 29, 2018). "Fueling the Firefighters: What California's First Responders Eat". Eater. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

Davis, Makenzie (August 15, 2018). "Away from home, firefighters give their all". Lassen County Times. Archived from the original on July 14, 2024. Retrieved September 8, 2018. - ^ Coury, Nic (August 11, 2016). "A glance at firefighters' favorite snacks while they're on shift". Monterey County Weekly. Archived from the original on July 14, 2024. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

Mejia, Brittny (December 7, 2017). "What do hungry firefighters eat for breakfast? Try 10,000 eggs and 4,500 strips of bacon". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018. - ^ a b c d e David Streitfeld for the LA Times (February 8, 2003). "Who Owns the Crustless PB&J?". The Tribune. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Smucker's Products". Smuckers. Archived from the original on July 14, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "Chubby Snacks Products". Chubby Snacks. Archived from the original on July 14, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ a b Keith Nunes (March 15, 2023). "Smucker reveals its Uncrustables secret". Food Business News. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ Burneko, Albert (June 1, 2013). "Taste Test: Uncrustables. What Does The Crustless PB&J Say About Us?". Deadspin. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ "The J. M. Smucker Company Announces Fourth Quarter and Full-Year Results" (Press release). The J.M. Smucker Co. June 16, 2005. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ Doering, Christopher (November 19, 2021). "J.M. Smucker to build $1.1B plant for Uncrustables, creating up to 750 jobs". FoodDive. Archived from the original on July 14, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ Monica Watrous (May 30, 2022). "Chubby Snacks to take on Uncrustables". Baking Business. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ "Chubby Snacks Announces Launch of New Shape and Flavors". PR Newswire. February 4, 2021. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ Lucas Cuni-Mertz (February 13, 2023). "Winning big with snack innovation". Food Business News.

- ^ Monica Watrous (November 21, 2023). "'A new beginning' for Chubby Snacks". Food Business News.

- ^ a b Dennis Lee (January 4, 2023). "Smucker's Tells Other Crustless Sandwiches to Cease and Desist". The Takeout. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ a b See the discussion in Jaffe and Lerner (2004).

- ^ "Albie's Foods, Inc. v. Menusaver, Inc., 170 F. Supp. 2d 736 (E.D. Mich. 2001)". Justia Law. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

References

- Adam B. Jaffe and Josh Lerner, Innovation and its Discontents: How our broken patent system is endangering innovation and progress, and what to do about it (ISBN 0-691-11725-X; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004), 25–26, 32–34.