1960s in history

This article is an orphan, as no other articles link to it. Please introduce links to this page from related articles; try the Find link tool for suggestions. (December 2024) |

An editor has nominated this article for deletion. You are welcome to participate in the deletion discussion, which will decide whether or not to retain it. |

World events

[edit]Cuba conflicts

[edit]The Bay of Pigs Invasion (Spanish: Invasión de Bahía de Cochinos, sometimes called Invasión de Playa Girón or Batalla de Playa Girón after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in April 1961 by the United States of America and the Cuban Democratic Revolutionary Front (DRF), consisting of Cuban exiles who opposed Fidel Castro's Cuban Revolution, clandestinely and directly financed by the U.S. government. The operation took place at the height of the Cold War, and its failure influenced relations between Cuba, the United States, and the Soviet Union.

In 1952, the American-allied dictator General Fulgencio Batista led a coup against President Carlos Prío and forced Prío into exile in Miami, Florida. Prío's exile inspired Castro's 26th of July Movement against Batista. The movement succeeded in overthrowing Batista during the Cuban Revolution in January 1959. Castro nationalized American businesses, including banks, oil refineries, and sugar and coffee plantations. By early 1960, President Eisenhower had begun contemplating ways to remove Castro, in the hopes that he might be replaced by a Cuban government-in-exile, though none existed at the time.[1] In accordance with this goal, Eisenhower eventually approved Richard Bissell's plan which included training the paramilitary force that would later be used in the Bay of Pigs Invasion.[2] Alongside covert operations, the U.S. also began its embargo of the island. This led Castro to reach out to its Cold War rival, the Soviet Union, after which the US severed diplomatic relations.

Cuban exiles who had moved to the U.S. following Castro's takeover had formed the counter-revolutionary military unit Brigade 2506, which was the armed wing of the DRF. The CIA funded the brigade, which also included approximately 60 members of the Alabama Air National Guard,[3] and trained the unit in Guatemala.

Over 1,400 paramilitaries, divided into five infantry battalions and one paratrooper battalion, assembled and launched from Guatemala and Nicaragua by boat on 17 April 1961. Two days earlier, eight CIA-supplied B-26 bombers had attacked Cuban airfields and then returned to the U.S. On the night of 17 April, the main invasion force landed on the beach at Playa Girón in the Bay of Pigs, where it overwhelmed a local revolutionary militia. Initially, José Ramón Fernández led the Cuban Revolutionary Army counter-offensive; later, Castro took personal control.

As the invasion force lost the strategic initiative, the international community found out about the invasion, and U.S. President John F. Kennedy decided to withhold further air support.[4] The plan, devised during Eisenhower's presidency, had required the involvement of U.S. air and naval forces. Without further air support, the invasion was being conducted with fewer forces than the CIA had deemed necessary. The invading force was defeated within three days by the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces (Spanish: Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias – FAR) and surrendered on 20 April. Most of the surrendered counter-revolutionary troops were publicly interrogated and put into Cuban prisons with further prosecution.

The invasion was a U.S. foreign policy failure. The Cuban government's victory solidified Castro's role as a national hero and widened the political division between the two formerly allied countries, as well as emboldened other Latin American groups to undermine U.S. influence in the region. As stated in a memoir from Chester Bowles: "The humiliating failure of the invasion shattered the myth of a New Frontier run by a new breed of incisive, fault-free supermen. However costly, it may have been a necessary lesson." It also pushed Cuba closer to the Soviet Union, setting the stage for the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962.The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (Spanish: Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (Russian: Карибский кризис, romanized: Karibskiy krizis), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of nuclear missiles in Italy and Turkey were matched by Soviet deployments of nuclear missiles in Cuba. The crisis lasted from 16 to 28 October 1962. The confrontation is widely considered to have been the closest the Cold War came to escalating into nuclear war.[5]

In 1961 the US government had installed Jupiter nuclear missiles in Italy and Turkey. It had also trained a paramilitary force of expatriate Cubans which the CIA led in an attempt to invade Cuba and overthrow its government. Starting in November 1961, the US government engaged in a violent campaign of terrorism and sabotage in Cuba, referred to as the Cuban Project, which continued throughout the first half of the 1960s. The Soviet administration was concerned about a Cuban drift towards China, with which country the Soviets had an increasingly fractious relationship. The Soviet and Cuban governments agreed, at a meeting between leaders Nikita Khrushchev and Fidel Castro in July 1962, to place nuclear missiles on Cuba to deter any future US invasion, and construction of missile launch facilities on Cuba was commenced.

A U-2 spy plane captured photographic evidence of medium and long range launch facilities in October 1962. US President John F. Kennedy convened a meeting of the National Security Council and other key advisers and formed the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (EXCOMM). Kennedy was advised to carry out an air strike on Cuba to delay Soviet missile supplies and follow this with an invasion of the Cuban mainland. He chose a less aggressive course in order to avoid having to declare war. On 22 October, Kennedy ordered a naval blockade by the US to prevent further missiles from reaching Cuba.[6] He referred to the blockade as a "quarantine" so that the US could avoid the formal implications of a state of war.[7]

An agreement was eventually reached between Kennedy and Khrushchev. The Soviets would dismantle their offensive weapons in Cuba, subject to United Nations verification, in exchange for a US public declaration and an agreement not to invade Cuba again. The United States secretly agreed to dismantle all the offensive weapons it had deployed in Turkey. There has been debate on whether Italy was also included in this agreement. While the Soviets dismantled their missiles, some Soviet bombers remained in Cuba and the United States kept the naval quarantine in place until 20 November 1962.[7][8] The blockade was formally ended on 20 November after all offensive missiles and bombers had been withdrawn. The evident necessity of a quick and direct communication line between the two powers resulted in the establishing of a Moscow–Washington hotline. A series of agreements later reduced US–Soviet tensions for several years.

This compromise embarrassed Khrushchev and the Soviet Union. The withdrawal of US missiles from Italy and Turkey had been a secret deal between Kennedy and Khrushchev, and the Soviets appeared to be retreating from a situation that they had started. Khrushchev's fall from power two years later was in part because of the Soviet Politburo's embarrassment at Khrushchev's eventual concessions to the US and his ineptitude in precipitating the crisis. According to the Soviet Ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Dobrynin, the top Soviet leadership took the Cuban outcome as "a blow to its prestige bordering on humiliation".[9][10]Vietnam War

[edit]

In the 1960 U.S. presidential election, Senator John F. Kennedy defeated incumbent Vice President Richard Nixon. Although Eisenhower warned Kennedy about Laos and Vietnam, Europe and Latin America "loomed larger than Asia on his sights."[11]: 264

The Kennedy administration remained committed to the Cold War foreign policy inherited from the Truman and Eisenhower administrations. In 1961, the US had 50,000 troops based in South Korea, and Kennedy faced four crisis situations: the failure of the Bay of Pigs Invasion he had approved in April,[12] settlement negotiations between the pro-Western government of Laos and the Pathet Lao communist movement in May,[11]: 265 construction of the Berlin Wall in August, and the Cuban Missile Crisis in October. Kennedy believed another failure to stop communist expansion would irreparably damage US credibility. He was determined to "draw a line in the sand" and prevent a communist victory in Vietnam. He told James Reston of The New York Times after the Vienna summit with Khrushchev, "Now we have a problem making our power credible and Vietnam looks like the place."[13][14]

Kennedy's policy toward South Vietnam assumed Diệm and his forces had to defeat the guerrillas on their own. He was against the deployment of American combat troops and observed "to introduce U.S. forces in large numbers there today, while it might have an initially favorable military impact, would almost certainly lead to adverse political and, in the long run, adverse military consequences."[15] The quality of the South Vietnamese military, however, remained poor. Poor leadership, corruption, and political promotions weakened the ARVN. The frequency of guerrilla attacks rose as the insurgency gathered steam. While Hanoi's support for the VC played a role, South Vietnamese governmental incompetence was at the core of the crisis.[16]: 369

One major issue Kennedy raised was whether the Soviet space and missile programs had surpassed those of the US. Although Kennedy stressed long-range missile parity with the Soviets, he was interested in using special forces for counterinsurgency warfare in Third World countries threatened by communist insurgencies. Although they were intended for use behind front lines after a conventional Soviet invasion of Europe, Kennedy believed guerrilla tactics employed by special forces, such as the Green Berets, would be effective in a "brush fire" war in Vietnam.

Kennedy advisors Maxwell Taylor and Walt Rostow recommended US troops be sent to South Vietnam disguised as flood relief workers.[17] Kennedy rejected the idea but increased military assistance. In April 1962, John Kenneth Galbraith warned Kennedy of the "danger we shall replace the French as a colonial force in the area and bleed as the French did."[18] Eisenhower put 900 advisors in Vietnam, and by November 1963, Kennedy had put 16,000 military personnel there.[19]: 131

The Strategic Hamlet Program was initiated in late 1961. This joint U.S.–South Vietnamese program attempted to resettle the rural population into fortified villages. It was implemented in early 1962 and involved some forced relocation and segregation of rural South Vietnamese, into new communities where the peasantry would be isolated from the VC. It was hoped these new communities would provide security for the peasants and strengthen the tie between them and the central government. However, by November 1963 the program had waned, and it ended in 1964.[20]: 1070 In July 1962, 14 nations, including China, South Vietnam, the Soviet Union, North Vietnam, and the US, signed an agreement promising to respect Laos' neutrality.

On 2 August 1964, USS Maddox, on an intelligence mission along North Vietnam's coast, fired upon and damaged torpedo boats approaching it in the Gulf of Tonkin.[21]: 124 A second attack was reported two days later on USS Turner Joy and Maddox. The circumstances were murky.[19]: 218–219 Johnson commented to Undersecretary of State George Ball that "those sailors out there may have been shooting at flying fish."[22] An NSA publication declassified in 2005 revealed there was no attack on 4 August.[23]

The second "attack" led to retaliatory airstrikes, and prompted Congress to approve the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on 7 August 1964.[24]: 78 The resolution granted the president power "to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression" and Johnson relied on this as giving him authority to expand the war.[19]: 221 Johnson pledged he was not "committing American boys to fighting a war that I think ought to be fought by the boys of Asia to help protect their own land".[19]: 227

The National Security Council recommended a three-stage escalation of the bombing of North Vietnam. Following an attack on a U.S. Army base on 7 February 1965,[25] airstrikes were initiated, while Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin was on a state visit to North Vietnam. Operation Rolling Thunder and Operation Arc Light expanded aerial bombardment and ground support operations.[26] The bombing campaign, which lasted three years, was intended to force North Vietnam to cease its support for the VC by threatening to destroy North Vietnamese air defenses and infrastructure. It was additionally aimed at bolstering South Vietnamese morale.[27] Between March 1965 and November 1968, Rolling Thunder deluged the north with a million tons of missiles, rockets and bombs.[11]: 468Mideast conflicts

[edit]The Six-Day War,[a] also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states, primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10 June 1967.

Military hostilities broke out amid poor relations between Israel and its Arab neighbors, which had been observing the 1949 Armistice Agreements signed at the end of the First Arab–Israeli War. In 1956, regional tensions over the Straits of Tiran (giving access to Eilat, a port on the southeast tip of Israel) escalated in what became known as the Suez Crisis, when Israel invaded Egypt over the Egyptian closure of maritime passageways to Israeli shipping, ultimately resulting in the re-opening of the Straits of Tiran to Israel as well as the deployment of the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) along the Egypt–Israel border.[28] In the months prior to the outbreak of the Six-Day War in June 1967, tensions again became dangerously heightened: Israel reiterated its post-1956 position that another Egyptian closure of the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping would be a definite casus belli. In May 1967, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser announced that the Straits of Tiran would again be closed to Israeli vessels. He subsequently mobilized the Egyptian military into defensive lines along the border with Israel[29] and ordered the immediate withdrawal of all UNEF personnel.[30][31]

On 5 June 1967, as the UNEF was in the process of leaving the zone, Israel launched a series of airstrikes against Egyptian airfields and other facilities.[31] Egyptian forces were caught by surprise, and nearly all of Egypt's military aerial assets were destroyed, giving Israel air supremacy. Simultaneously, the Israeli military launched a ground offensive into Egypt's Sinai Peninsula as well as the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip. After some initial resistance, Nasser ordered an evacuation of the Sinai Peninsula; by the sixth day of the conflict, Israel had occupied the entire Sinai Peninsula.[32] Jordan, which had entered into a defense pact with Egypt just a week before the war began, did not take on an all-out offensive role against Israel, but launched attacks against Israeli forces to slow Israel's advance.[33] On the fifth day, Syria joined the war by shelling Israeli positions in the north.[34]

Egypt and Jordan agreed to a ceasefire on 8 June, and Syria on 9 June, and it was signed with Israel on 11 June. The Six-Day War resulted in more than 15,000 Arab fatalities, while Israel suffered fewer than 1,000. Alongside the combatant casualties were the deaths of 20 Israeli civilians killed in Arab forces air strikes on Jerusalem, 15 UN peacekeepers killed by Israeli strikes in the Sinai at the outset of the war, and 34 US personnel killed in the USS Liberty incident in which Israeli air forces struck a United States Navy technical research ship.

At the time of the cessation of hostilities, Israel had occupied the Golan Heights from Syria, the West Bank including East Jerusalem from Jordan, and the Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip from Egypt. The displacement of civilian populations as a result of the Six-Day War would have long-term consequences, as around 280,000 to 325,000 Palestinians and 100,000 Syrians fled or were expelled from the West Bank[35] and the Golan Heights, respectively.[36] Nasser resigned in shame after Israel's victory, but was later reinstated following a series of protests across Egypt. In the aftermath of the conflict, Egypt closed the Suez Canal until 1975.[37]Space

[edit]

A Moon landing or lunar landing is the arrival of a spacecraft on the surface of the Moon, including both crewed and robotic missions. The first human-made object to touch the Moon was Luna 2 in 1959.[40]

In 1969 Apollo 11 was the first crewed mission to land on the Moon.[41] There were six crewed landings between 1969 and 1972, and numerous uncrewed landings. All crewed missions to the Moon were conducted by the Apollo program, with the last departing the lunar surface in December 1972. After Luna 24 in 1976 there were no soft landings on the Moon until Chang'e 3 in 2013. All soft landings took place on the near side of the Moon until January 2019, when Chang'e 4 made the first landing on the far side of the Moon.[42]Science and technology

[edit]Computing

[edit]The mass increase in the use of computers accelerated with Third Generation computers starting around 1966 in the commercial market. These generally relied on early (sub-1000 transistor) integrated circuit technology. The third generation ends with the microprocessor-based fourth generation.

In 1958, Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments invented the hybrid integrated circuit (hybrid IC),[43] which had external wire connections, making it difficult to mass-produce.[44] In 1959, Robert Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor invented the monolithic integrated circuit (IC) chip.[45][44] It was made of silicon, whereas Kilby's chip was made of germanium. The basis for Noyce's monolithic IC was Fairchild's planar process, which allowed integrated circuits to be laid out using the same principles as those of printed circuits. The planar process was developed by Noyce's colleague Jean Hoerni in early 1959, based on the silicon surface passivation and thermal oxidation processes developed by Carl Frosch and Lincoln Derrick in 1955 and 1957.[46][47][48][49][50][51]

Computers using IC chips began to appear in the early 1960s. For example, the 1961 Semiconductor Network Computer (Molecular Electronic Computer, Mol-E-Com),[52][53][54] the first monolithic integrated circuit[55][56][57] general purpose computer (built for demonstration purposes, programmed to simulate a desk calculator) was built by Texas Instruments for the US Air Force.[58][59][60][61]

Some of their early uses were in embedded systems, notably used by NASA for the Apollo Guidance Computer, by the military in the LGM-30 Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missile, the Honeywell ALERT airborne computer,[62][63] and in the Central Air Data Computer used for flight control in the US Navy's F-14A Tomcat fighter jet.

An early commercial use was the 1965 SDS 92.[64][65] IBM first used ICs in computers for the logic of the System/360 Model 85 shipped in 1969 and then made extensive use of ICs in its System/370 which began shipment in 1971.

The integrated circuit enabled the development of much smaller computers. The minicomputer was a significant innovation in the 1960s and 1970s. It brought computing power to more people, not only through more convenient physical size but also through broadening the computer vendor field. Digital Equipment Corporation became the number two computer company behind IBM with their popular PDP and VAX computer systems. Smaller, affordable hardware also brought about the development of important new operating systems such as Unix.

In November 1966, Hewlett-Packard introduced the 2116A[66][67] minicomputer, one of the first commercial 16-bit computers. It used CTμL (Complementary Transistor MicroLogic)[68] in integrated circuits from Fairchild Semiconductor. Hewlett-Packard followed this with similar 16-bit computers, such as the 2115A in 1967,[69] the 2114A in 1968,[70] and others.

In 1969, Data General introduced the Nova and shipped a total of 50,000 at $8,000 each. The popularity of 16-bit computers, such as the Hewlett-Packard 21xx series and the Data General Nova, led the way toward word lengths that were multiples of the 8-bit byte. The Nova was first to employ medium-scale integration (MSI) circuits from Fairchild Semiconductor, with subsequent models using large-scale integrated (LSI) circuits. Also notable was that the entire central processor was contained on one 15-inch printed circuit board.

Large mainframe computers used ICs to increase storage and processing abilities. The 1965 IBM System/360 mainframe computer family are sometimes called third-generation computers; however, their logic consisted primarily of SLT hybrid circuits, which contained discrete transistors and diodes interconnected on a substrate with printed wires and printed passive components; the S/360 M85 and M91 did use ICs for some of their circuits. IBM's 1971 System/370 used ICs for their logic, and later models used semiconductor memory.

By 1971, the ILLIAC IV supercomputer was the fastest computer in the world, using about a quarter-million small-scale ECL logic gate integrated circuits to make up sixty-four parallel data processors.[71]

Third-generation computers were offered well into the 1990s; for example the IBM ES9000 9X2 announced April 1994[72] used 5,960 ECL chips to make a 10-way processor.[73] Other third-generation computers offered in the 1990s included the DEC VAX 9000 (1989), built from ECL gate arrays and custom chips,[74] and the Cray T90 (1995).The first integrated circuits contained only a few transistors. Early digital circuits containing tens of transistors provided a few logic gates, and early linear ICs such as the Plessey SL201 or the Philips TAA320 had as few as two transistors. The number of transistors in an integrated circuit has increased dramatically since then. The term "large scale integration" (LSI) was first used by IBM scientist Rolf Landauer when describing the theoretical concept;[75] that term gave rise to the terms "small-scale integration" (SSI), "medium-scale integration" (MSI), "very-large-scale integration" (VLSI), and "ultra-large-scale integration" (ULSI). The early integrated circuits were SSI.

SSI circuits were crucial to early aerospace projects, and aerospace projects helped inspire development of the technology. Both the Minuteman missile and Apollo program needed lightweight digital computers for their inertial guidance systems. Although the Apollo Guidance Computer led and motivated integrated-circuit technology,[76] it was the Minuteman missile that forced it into mass-production. The Minuteman missile program and various other United States Navy programs accounted for the total $4 million integrated circuit market in 1962, and by 1968, U.S. Government spending on space and defense still accounted for 37% of the $312 million total production.

The demand by the U.S. Government supported the nascent integrated circuit market until costs fell enough to allow IC firms to penetrate the industrial market and eventually the consumer market. The average price per integrated circuit dropped from $50 in 1962 to $2.33 in 1968.[77] Integrated circuits began to appear in consumer products by the turn of the 1970s decade. A typical application was FM inter-carrier sound processing in television receivers.

The first application MOS chips were small-scale integration (SSI) chips.[78] Following Mohamed M. Atalla's proposal of the MOS integrated circuit chip in 1960,[79] the earliest experimental MOS chip to be fabricated was a 16-transistor chip built by Fred Heiman and Steven Hofstein at RCA in 1962.[80] The first practical application of MOS SSI chips was for NASA satellites.[78]Arts and culture

[edit]Music

[edit]

"The 60s were a leap in human consciousness. Mahatma Gandhi, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Che Guevara, Mother Teresa, they led a revolution of conscience. The Beatles, The Doors, Jimi Hendrix created revolution and evolution themes. The music was like Dalí, with many colors and revolutionary ways. The youth of today must go there to find themselves."

The rock 'n' roll movement of the 1950s quickly came to an end in 1959 with the Day the Music Died (as explained in the song "American Pie"), the scandal of Jerry Lee Lewis' marriage to his 13-year-old cousin, and the induction of Elvis Presley into the United States Army. As the 1960s began, the major rock 'n' roll stars of the '50s such as Chuck Berry and Little Richard had dropped off the charts and popular music in the U.S. came to be dominated by girl groups, surf music, novelty pop songs, clean-cut teen idols, and Motown music. Another important change in music during the early 1960s was the American folk music revival which introduced Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, The Kingston Trio, Harry Belafonte, Odetta, Phil Ochs, and many other singer-songwriters to the public.

Girl groups and female singers, such as the Shirelles, Betty Everett, Little Eva, the Dixie Cups, the Ronettes, Martha and the Vandellas and the Supremes dominated the charts in the early 1960s. This style consisted typically of light pop themes about teenage romance and lifestyles, backed by vocal harmonies and a strong rhythm. Most girl groups were African-American, but white girl groups and singers, such as Lesley Gore, the Angels, and the Shangri-Las also emerged during this period.

Around the same time, record producer Phil Spector began producing girl groups and created a new kind of pop music production that came to be known as the Wall of Sound. This style emphasized higher budgets and more elaborate arrangements, and more melodramatic musical themes in place of a simple, light-hearted pop sound. Spector's innovations became integral to the growing sophistication of popular music from 1965 onward.

Also during the early 1960s, surf rock emerged, a rock subgenre that was centered in Southern California and based on beach and surfing themes, in addition to the usual songs about teenage romance and innocent fun. The Beach Boys quickly became the premier surf rock band and almost completely and single-handedly overshadowed the many lesser-known artists in the subgenre. Surf rock reached its peak in 1963–1965 before gradually being overtaken by bands influenced by the British Invasion and the counterculture movement.

The car song also emerged as a rock subgenre in the early 1960s, which focused on teenagers' fascination with car culture. The Beach Boys also dominated this subgenre, along with the duo Jan and Dean. Such notable songs include "Little Deuce Coupe", "409", and "Shut Down", all by the Beach Boys; Jan and Dean's "Little Old Lady from Pasadena" and "Drag City", Ronny and the Daytonas' "Little GTO", and many others. Like girl groups and surf rock, car songs also became overshadowed by the British Invasion and the counterculture movement.

The early 1960s also saw the golden age of another rock subgenre, the teen tragedy song, which focused on lost teen romance caused by sudden death, mainly in traffic accidents. Such songs included Mark Dinning's "Teen Angel", Ray Peterson's "Tell Laura I Love Her", Jan and Dean's "Dead Man's Curve", the Shangri-Las' "Leader of the Pack", and perhaps the subgenre's most popular, "Last Kiss" by J. Frank Wilson and the Cavaliers.

In the early 1960s, Britain became a hotbed of rock 'n' roll activity during this time. In late 1963, the Beatles embarked on their first US tour and cult singer Dusty Springfield released her first solo single. A few months later, rock 'n' roll founding father Chuck Berry emerged from a 2+1⁄2-year prison stint and resumed recording and touring. The stage was set for the spectacular revival of rock music.

In the UK, the Beatles played raucous rock 'n' roll – as well as doo wop, girl-group songs, show tunes – and wore leather jackets. Their manager Brian Epstein encouraged the group to wear suits. Beatlemania abruptly exploded after the group's appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. Late in 1965, the Beatles released the album Rubber Soul which marked the beginning of their transition to a sophisticated power pop group with elaborate studio arrangements and production, and a year after that, they gave up touring entirely to focus only on albums. A host of imitators followed the Beatles in the so-called British Invasion, including groups like the Rolling Stones, the Who and the Kinks who would become legends in their own right.

As the counterculture movement developed, artists began making new kinds of music influenced by the use of psychedelic drugs. Guitarist Jimi Hendrix emerged onto the scene in 1967 with a radically new approach to electric guitar that replaced Chuck Berry, previously seen as the gold standard of rock guitar. Rock artists began to take on serious themes and social commentary/protest instead of simplistic pop themes.

A major development in popular music during the mid-1960s was the movement away from singles and towards albums. Previously, popular music was based around the 45 single (or even earlier, the 78 single) and albums such as they existed were little more than a hit single or two backed with filler tracks, instrumentals, and covers. The development of the AOR (album-oriented rock) format was complicated and involved several concurrent events such as Phil Spector's Wall of Sound, the introduction by Bob Dylan of "serious" lyrics to rock music, and the Beatles' new studio-based approach. In any case, after 1965 the vinyl LP had definitively taken over as the primary format for all popular music styles.

Blues also continued to develop strongly during the '60s, but after 1965, it increasingly shifted to the young white rock audience and away from its traditional black audience, which moved on to other styles such as soul and funk.

Jazz music and pop standards during the first half of the 1960s was largely a continuation of 1950s styles, retaining its core audience of young, urban, college-educated whites. By 1967, the death of several important jazz figures such as John Coltrane and Nat King Cole precipitated a decline in the genre. The takeover of rock in the late 1960s largely spelled the end of jazz and standards as mainstream forms of music, after they had dominated much of the first half of the 20th century.

Country music gained popularity on the West Coast, due in large part to the Bakersfield sound, led by Buck Owens and Merle Haggard. Female country artists were also becoming more mainstream (in a genre dominated by men in previous decades), with such acts as Patsy Cline, Loretta Lynn, and Tammy Wynette.

Late 1960s also was the beginning of disco music, which became more popular in 1970s.Social movements

[edit]

The counterculture of the 1960s was an anti-establishment cultural phenomenon and political movement that developed in the Western world during the mid-20th century. It began in the early 1960s, and continued through the early 1970s.[82] It is often synonymous with cultural liberalism and with the various social changes of the decade. The effects of the movement[82] have been ongoing to the present day. The aggregate movement gained momentum as the civil rights movement in the United States had made significant progress, such as the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and with the intensification of the Vietnam War that same year, it became revolutionary to some.[83][84][85] As the movement progressed, widespread social tensions also developed concerning other issues, and tended to flow along generational lines regarding respect for the individual, human sexuality, women's rights, traditional modes of authority, rights of people of color, end of racial segregation, experimentation with psychoactive drugs, and differing interpretations of the American Dream. Many key movements related to these issues were born or advanced within the counterculture of the 1960s.[86]

As the era unfolded, what emerged were new cultural forms and a dynamic subculture that celebrated experimentation, individuality,[87] modern incarnations of Bohemianism, and the rise of the hippie and other alternative lifestyles. This embrace of experimentation is particularly notable in the works of popular musical acts such as the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin and Bob Dylan, as well as of New Hollywood, French New Wave, and Japanese New Wave filmmakers, whose works became far less restricted by censorship. Within and across many disciplines, many other creative artists, authors, and thinkers helped define the counterculture movement. Everyday fashion experienced a decline of the suit and especially of the wearing of hats; other changes included the normalisation of long hair worn down for women (as well as many men at the time),[88] the popularization of traditional African, Indian and Middle Eastern styles of dress (including the wearing of natural hair for those of African descent), the invention and popularization of the miniskirt which raised hemlines above the knees, as well as the development of distinguished, youth-led fashion subcultures. Styles based around jeans, for both men and women, became an important fashion movement that has continued up to the present day.

Several factors distinguished the counterculture of the 1960s from anti-authoritarian movements of previous eras. The post-World War II baby boom[89][90] generated an unprecedented number of potentially disaffected youth as prospective participants in a rethinking of the direction of the United States and other democratic societies.[91] Post-war affluence allowed much of the counterculture generation to move beyond the provision of the material necessities of life that had preoccupied their Depression-era parents.[92] The era was also notable in that a significant portion of the array of behaviors and "causes" within the larger movement were quickly assimilated within mainstream society, particularly in the US, even though counterculture participants numbered in the clear minority within their respective national populations.[93][94]Africa

[edit]Egypt

[edit]

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein[b] (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-reaching land reforms the following year. Following a 1954 attempt on his life by a Muslim Brotherhood member, he cracked down on the organization, put President Mohamed Naguib under house arrest and assumed executive office. He was formally elected president in June 1956.

Nasser's popularity in Egypt and the Arab world skyrocketed after his nationalization of the Suez Canal Company and his political victory in the subsequent Suez Crisis, known in Egypt as the Tripartite Aggression. Calls for pan-Arab unity under his leadership increased, culminating with the formation of the United Arab Republic with Syria from 1958 to 1961. In 1962, Nasser began a series of major socialist measures and modernization reforms in Egypt. Despite setbacks to his pan-Arabist cause, by 1963 Nasser's supporters gained power in several Arab countries, but he became embroiled in the North Yemen Civil War, and eventually the much larger Arab Cold War. He began his second presidential term in March 1965 after his political opponents were banned from running. Following Egypt's defeat by Israel in the Six-Day War of 1967, Nasser resigned, but he returned to office after popular demonstrations called for his reinstatement. By 1968, Nasser had appointed himself prime minister, launched the War of Attrition to regain the Israeli-occupied Sinai Peninsula, begun a process of depoliticizing the military, and issued a set of political liberalization reforms. After the conclusion of the 1970 Arab League summit, Nasser suffered a heart attack and died. His funeral in Cairo drew five to six million mourners, and prompted an outpouring of grief across the Arab world.

Nasser remains an iconic figure in the Arab world, particularly for his strides towards social justice and Arab unity, his modernization policies, and his anti-imperialist efforts. His presidency also encouraged and coincided with an Egyptian cultural boom, and the launching of large industrial projects, including the Aswan Dam, and Helwan city. Nasser's detractors criticize his authoritarianism, his human rights violations, his antisemitism, and the dominance of the military over civil institutions that characterised his tenure, establishing a pattern of military and dictatorial rule in Egypt which has persisted, nearly uninterrupted, to the present day.Asia

[edit]China

[edit]North Vietnam

[edit]

Hồ Chí Minh[c][d] (born Nguyễn Sinh Cung;[e][f][g][99][100] 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969),[h] colloquially known as Uncle Ho (Bác Hồ)[i][103] and by other aliases[j] and sobriquets,[k] was a Vietnamese revolutionary and politician who served as the founder and first president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam from 1945 until his death in 1969, and as its first prime minister from 1945 to 1955. Ideologically a Marxist–Leninist, he founded the Indochinese Communist Party in 1930 and its successor Workers' Party of Vietnam (later the Communist Party of Vietnam) in 1951, serving as the party's chairman until his death.

Hồ was born in Nghệ An province in French Indochina, and received a French education. Starting in 1911, he worked in various countries overseas, and in 1920 was a founding member of the French Communist Party in Paris. After studying in Moscow, Hồ founded the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League in 1925, which he transformed into the Indochinese Communist Party in 1930. On his return to Vietnam in 1941, he founded and led the Việt Minh independence movement against the Japanese, and in 1945 led the August Revolution against the monarchy and proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. After the French returned to power, Hồ's government retreated to the countryside and initiated guerrilla warfare from 1946.

Between 1953 and 1956, Hồ's leadership saw the implementation of a land reform campaign, which included executions and political purges.[106][107] The Việt Minh defeated the French in 1954 at the Battle of Điện Biên Phủ, ending the First Indochina War. At the 1954 Geneva Conference, Vietnam was divided into two de facto separate states, with the Việt Minh in control of North Vietnam, and anti-communists backed by the United States in control of South Vietnam. Hồ remained president and party leader during the Vietnam War, which began in 1955. He supported the Viet Cong insurgency in the south, overseeing the transport of troops and supplies on the Ho Chi Minh trail until his death in 1969. North Vietnam won in 1975, and the country was re-unified in 1976 as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Saigon – Gia Định, South Vietnam's former capital, was renamed Ho Chi Minh City in his honor.

The details of Hồ's life before he came to power in Vietnam are uncertain. He is known to have used between 50[108]: 582 and 200 pseudonyms.[109] Information on his birth and early life is ambiguous and subject to academic debate. At least four existing official biographies vary on names, dates, places, and other hard facts while unofficial biographies vary even more widely.[110] Aside from being a politician, Hồ was a writer, poet, and journalist. He wrote several books, articles, and poems in Chinese, Vietnamese, and French.South Vietnam

[edit]

Ngô Đình Diệm (/djɛm/ dyem,[111] /ˈjiːəm/ YEE-əm or /ziːm/ zeem; Vietnamese: [ŋō ɗìn jîəmˀ] ⓘ; 3 January 1901 – 2 November 1963) was a South Vietnamese politician who was the final prime minister of the State of Vietnam (1954–1955) and later the first president of South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) from 1955 until his capture and assassination during the CIA-backed 1963 coup d'état.

Diệm was born into a prominent Catholic family with his father, Ngô Đình Khả, being a high-ranking mandarin for Emperor Thành Thái during the French colonial era. Diệm was educated at French-speaking schools and considered following his brother Ngô Đình Thục into the priesthood, but eventually chose to pursue a career in the civil service. He progressed rapidly in the court of Emperor Bảo Đại, becoming governor of Bình Thuận Province in 1929 and interior minister in 1933. However, he resigned from the latter position after three months and publicly denounced the emperor as a tool of France. Diệm came to support Vietnamese nationalism, promoting both anti-communism, in opposition to Hồ Chí Minh, and decolonization, in opposition to Bảo Đại. He established the Cần Lao Party to support his political doctrine of Person Dignity Theory, which was heavily influenced by the teachings of Personalism, mainly from French philosopher Emmanuel Mounier, and Confucianism, which Diệm had greatly admired.

After several years in exile in Japan, the United States, and Europe, Diệm returned home in July 1954 and was appointed prime minister by Bảo Đại, against the French suggestion of Nguyen Ngoc Bich (a French-educated engineer, Francophile anticolonialist, a resistance hero in the First Indochina War, and medical doctor) as an alternative. The 1954 Geneva Conference took place soon after he took office, formally partitioning Vietnam along the 17th parallel. Diệm, with the aid of his younger brother Ngô Đình Nhu, soon consolidated power in South Vietnam. After the fraudulent 1955 State of Vietnam referendum, he proclaimed the creation of the Republic of Vietnam, with himself as president. His government was supported by other anti-communist countries, most notably the United States. Diệm pursued a series of nation-building projects, promoting industrial and rural development. From 1957 onward, as part of the Vietnam War, he faced a communist insurgency backed by North Vietnam, eventually formally organized under the banner of the Viet Cong. He was subject to several assassination and coup attempts, and in 1962 established the Strategic Hamlet Program as the cornerstone of his counterinsurgency effort.

In 1963, Diệm's favoritism towards Catholics and persecution of practitioners of Buddhism in Vietnam led to the Buddhist crisis. The event damaged relations with the United States and other previously sympathetic countries, and his organization lost favor with the leadership of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. On 1 November 1963, the country's leading generals launched a coup d'état with assistance from the Central Intelligence Agency. Diệm and his brother, Nhu, initially escaped, but were recaptured the following day and assassinated on the orders of Dương Văn Minh, who succeeded him as president.

Diệm has been a controversial historical figure. Some historians have considered him a tool of the United States, while others portrayed him as an avatar of Vietnamese tradition. At the time of his assassination, he was widely considered to be a corrupt dictator.

The Diệm government lost support among the populace, and from the Kennedy administration, due to its repression of Buddhists and military defeats by the Việt Cộng. Notably, the Huế Phật Đản shootings of 8 May 1963 led to the Buddhist crisis, provoking widespread protests and civil resistance. The situation came to a head when the Special Forces were sent to raid Buddhist temples across the country, leaving a death toll estimated to be in the hundreds. Diệm was overthrown in a coup on 1 November 1963 with the tacit approval of the US.[citation needed]

Diệm's removal and assassination set off a period of political instability and declining legitimacy of the Saigon government. General Dương Văn Minh became president, but he was ousted in January 1964 by General Nguyễn Khánh. Phan Khắc Sửu was named head of state, but power remained with a junta of generals led by Khánh, which soon fell to infighting. Meanwhile, the Gulf of Tonkin incident of 2 August 1964 led to a dramatic increase in direct American participation in the war, with nearly 200,000 troops deployed by the end of the year. Khánh sought to capitalize on the crisis with the Vũng Tàu Charter, a new constitution that would have curtailed civil liberties and concentrated his power, but was forced to back down in the face of widespread protests and strikes. Coup attempts followed in September and February 1965, the latter resulting in Air Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ becoming prime minister and General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu becoming nominal head of state.

Kỳ and Thieu functioned in those roles until 1967, bringing much-desired stability to the government. They imposed censorship and suspended civil liberties, and intensified anticommunist efforts. Under pressure from the US, they held elections for president and the legislature in 1967. The Senate election took place on 2 September 1967. The Presidential election took place on 3 September 1967, Thiệu was elected president with 34% of the vote in a widely criticised poll. The Parliamentary election took place on 22 October 1967.

On 31 January 1968, the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and the Việt Cộng broke the traditional truce accompanying the Tết (Lunar New Year) holiday. The Tet Offensive failed to spark a national uprising and was militarily disastrous. By bringing the war to South Vietnam's cities, however, and by demonstrating the continued strength of communist forces, it marked a turning point in US support for the government in South Vietnam. The new administration of Richard Nixon introduced a policy of Vietnamization to reduce US combat involvement and began negotiations with the North Vietnamese to end the war. Thiệu used the aftermath of the Tet Offensive to sideline Kỳ, his chief rival.

On 26 March 1970 the government began to implement the Land-to-the-Tiller program of land reform with the US providing US$339m of the program's US$441m cost. Individual landholdings were limited to 15 hectares.

US and South Vietnamese forces launched a series of attacks on PAVN/VC bases in Cambodia in April–July 1970. South Vietnam launched an invasion of North Vietnamese bases in Laos in February/March 1971 and were defeated by the PAVN in what was widely regarded as a setback for Vietnamization.

Thiệu was reelected unopposed in the Presidential election on 2 October 1971.

North Vietnam launched a conventional invasion of South Vietnam in late March 1972 which was only finally repulsed by October with massive US air support.Europe

[edit]Czechoslovakia

[edit]The Prague Spring (Czech: Pražské jaro, Slovak: Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), and continued until 21 August 1968, when the Soviet Union and most Warsaw Pact members invaded the country to suppress the reforms.

The Prague Spring reforms were a strong attempt by Dubček to grant additional rights to the citizens of Czechoslovakia in an act of partial decentralization of the economy and democratization. The freedoms granted included a loosening of restrictions on the media, speech and travel. After national discussion of dividing the country into a federation of three republics, Bohemia, Moravia–Silesia and Slovakia, Dubček oversaw the decision to split into two, the Czech Socialist Republic and Slovak Socialist Republic.[112] This dual federation was the only formal change that survived the invasion.

The reforms, especially the decentralization of administrative authority, were not received well by the Soviets, who, after failed negotiations, sent half a million Warsaw Pact troops and tanks to occupy the country. The New York Times cited reports of 650,000 men equipped with the most modern and sophisticated weapons in the Soviet military catalogue.[113] A massive wave of emigration swept the nation. Resistance was mounted throughout the country, involving attempted fraternization, sabotage of street signs, defiance of curfews, etc. While the Soviet military had predicted that it would take four days to subdue the country, the resistance held out for almost eight months until diplomatic maneuvers finally circumvented it. It became a high-profile example of civilian-based defense; there were sporadic acts of violence and several protest suicides by self-immolation (the most famous being that of Jan Palach), but no military resistance. Czechoslovakia remained a Soviet satellite state until 1989 when the Velvet Revolution peacefully ended the communist regime; the last Soviet troops left the country in 1991.

After the invasion, Czechoslovakia entered a period known as normalization (Czech: normalizace, Slovak: normalizácia), in which new leaders attempted to restore the political and economic values that had prevailed before Dubček gained control of the KSČ. Gustáv Husák, who replaced Dubček as First Secretary and also became President, reversed almost all of the reforms. The Prague Spring inspired music and literature including the work of Václav Havel, Karel Husa, Karel Kryl and Milan Kundera's novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being.France

[edit]

Charles de Gaulle's tenure as the 18th president of France officially began on 8 January 1959. In 1958, during the Algerian War, he came out of retirement and was appointed President of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister) by President René Coty. He rewrote the Constitution of France and founded the Fifth Republic after approval by referendum. He was elected president later that year, a position to which he was re-elected in 1965 and held until his resignation on 28 April 1969.

When the war in Algeria threatened to bring the unstable Fourth Republic to collapse, the National Assembly brought him back to power during the May 1958 crisis. He founded the Fifth Republic with a strong presidency, and he was elected to continue in that role. He managed to keep France together while taking steps to end the war, much to the anger of the Pieds-Noirs (ethnic Europeans born in Algeria) and the armed forces. He granted independence to Algeria and acted progressively towards other French colonies. In the context of the Cold War, de Gaulle initiated his "politics of grandeur", asserting that France as a major power should not rely on other countries, such as the United States, for its national security and prosperity. To this end, he pursued a policy of "national independence" which led him to withdraw from NATO's integrated military command and to launch an independent nuclear strike force that made France the world's fourth nuclear power. He restored cordial Franco-German relations to create a European counterweight between the Anglo-American and Soviet spheres of influence through the signing of the Élysée Treaty on 22 January 1963.

De Gaulle opposed any development of a supranational Europe, favouring Europe as a continent of sovereign nations. De Gaulle openly criticised the United States intervention in Vietnam. In his later years, his support for the slogan "Vive le Québec libre" and his two vetoes of Britain's entry into the European Economic Community generated considerable controversy in both North America and Europe. Although reelected to the presidency in 1965, he faced widespread protests by students and workers in May 1968, but had the Army's support and won an election with an increased majority in the National Assembly. De Gaulle resigned in 1969 after losing a referendum in which he proposed more decentralisation.De Gaulle's government was criticized within France, particularly for its heavy-handed style. While the written press and elections were free, and private stations such as Europe 1 were able to broadcast in French from abroad, the state's ORTF had a monopoly on television and radio. This monopoly meant that the government was in a position to directly influence broadcast news. In many respects, Gaullist France was conservative, Catholic, and there were few women in high-level political posts (in May 1968, the government's ministers were 100% male).[114] Many factors contributed to a general weariness of sections of the public, particularly the student youth, which led to the events of May 1968.

The mass demonstrations and strikes in France in May 1968 severely challenged De Gaulle's legitimacy. He and other government leaders feared that the country was on the brink of revolution or civil war. On 29 May, De Gaulle disappeared without notifying Prime Minister Pompidou or anyone else in the government, stunning the country. He fled to Baden-Baden in Germany to meet with General Massu, head of the French military there, to discuss possible army intervention against the protesters. De Gaulle returned to France after being assured of the military's support, in return for which De Gaulle agreed to amnesty for the 1961 coup plotters and OAS members.[115][116]

In a private meeting discussing the students' and workers' demands for direct participation in business and government he coined the phrase "La réforme oui, la chienlit non", which can be politely translated as 'reform yes, masquerade/chaos no.' It was a vernacular scatological pun meaning 'chie-en-lit, no' (shit-in-bed, no). The term is now common parlance in French political commentary, used both critically and ironically referring back to de Gaulle.[117]

But de Gaulle offered to accept some of the reforms the demonstrators sought. He again considered a referendum to support his moves, but on 30 May, Pompidou persuaded him to dissolve parliament (in which the government had all but lost its majority in the March 1967 elections) and hold new elections instead. The June 1968 elections were a major success for the Gaullists and their allies; when shown the spectre of revolution or civil war, the majority of the country rallied to him. His party won 352 of 487 seats,[118] but de Gaulle remained personally unpopular; a survey conducted immediately after the crisis showed that a majority of the country saw him as too old, too self-centered, too authoritarian, too conservative, and too anti-American.[115]Soviet Union

[edit]The Khrushchev Thaw (Russian: хрущёвская о́ттепель, romanized: khrushchovskaya ottepel, IPA: [xrʊˈɕːɵfskəjə ˈotʲːɪpʲɪlʲ] or simply ottepel)[119] is the period from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s when repression and censorship in the Soviet Union were relaxed due to Nikita Khrushchev's policies of de-Stalinization[120] and peaceful coexistence with other nations. The term was coined after Ilya Ehrenburg's 1954 novel The Thaw ("Оттепель"),[121] sensational for its time.

The Thaw became possible after the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953. First Secretary Khrushchev denounced former General Secretary Stalin[122] in the "Secret Speech" at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party,[123][124] then ousted the Stalinists during his power struggle in the Kremlin. The Thaw was highlighted by Khrushchev's 1954 visit to Beijing, China, his 1955 visit to Belgrade, Yugoslavia (with whom relations had soured since the Tito–Stalin Split in 1948), and his subsequent meeting with Dwight Eisenhower later that year, culminating in Khrushchev's 1959 visit to the United States.

The Thaw allowed some freedom of information in the media, arts, and culture; international festivals; foreign films; uncensored books; and new forms of entertainment on the emerging national TV, ranging from massive parades and celebrations to popular music and variety shows, satire and comedies, and all-star shows[125] like Goluboy Ogonyok. Such political and cultural updates altogether had a significant influence on the public consciousness of several generations of people in the Soviet Union.[126][127]

Leonid Brezhnev, who succeeded Khrushchev, put an end to the Thaw. The 1965 economic reform of Alexei Kosygin was de facto discontinued by the end of the 1960s, while the trial of the writers Yuli Daniel and Andrei Sinyavsky in 1966—the first such public trial since Stalin's reign—and the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 signaled the reversal of Soviet liberalization.The 1965 Soviet economic reform, sometimes called the Kosygin reform (Russian: Косыгинская реформа) or Liberman reform, named after E.G. Liberman, was a set of planned changes in the economy of the USSR. A centerpiece of these changes was the introduction of profitability and sales as the two key indicators of enterprise success. Some of an enterprise's profits would go to three funds, used to reward workers and expand operations; most would go to the central budget.[128]

The reforms were introduced politically by Alexei Kosygin—who had just become Premier of the Soviet Union following the removal of Nikita Khrushchev—and ratified by the Central Committee in September 1965. They reflected some long-simmering wishes of the USSR's mathematically-oriented economic planners, and initiated the shift towards increased decentralization in the process of economic planning. The reforms, coinciding with the Eighth Five-Year Plan, led to continued growth of the Soviet economy. The success of said reforms was short-lived, and with the events of Prague in 1968, fueled by Moscow's implementation of the reforms in Eastern Bloc countries, led to the reforms being curtailed. Economists like Lev Gatovsky and Liberman were instrumental in framing the theoretical underpinnings of the Soviet economic reforms of the 1960s, advocating for the use of profit motives and market mechanisms within a socialist framework.[129][130][131]United Kingdom

[edit]

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963.[132] Nicknamed "Supermac", he was known for his pragmatism, wit, and unflappability.

Macmillan was seriously injured as an infantry officer during the First World War. He suffered pain and partial immobility for the rest of his life. After the war he joined his family book-publishing business, then entered Parliament at the 1924 general election for Stockton-on-Tees. Losing his seat in 1929, he regained it in 1931, soon after which he spoke out against the high rate of unemployment in Stockton. He opposed the appeasement of Germany practised by the Conservative government. He rose to high office during the Second World War as a protégé of Prime Minister Winston Churchill. In the 1950s Macmillan served as Foreign Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer under Anthony Eden.

When Eden resigned in 1957 following the Suez Crisis, Macmillan succeeded him as prime minister and Leader of the Conservative Party. He was a One Nation Tory of the Disraelian tradition and supported the post-war consensus. He supported the welfare state and the necessity of a mixed economy with some nationalised industries and strong trade unions. He championed a Keynesian strategy of deficit spending to maintain demand and pursuit of corporatist policies to develop the domestic market as the engine of growth. Benefiting from favourable international conditions,[133] he presided over an age of affluence, marked by low unemployment and high—if uneven—growth. In his speech of July 1957 he told the nation it had "never had it so good",[134] but warned of the dangers of inflation, summing up the fragile prosperity of the 1950s.[135] He led the Conservatives to success in 1959 with an increased majority.

In international affairs, Macmillan worked to rebuild the Special Relationship with the United States from the wreckage of the 1956 Suez Crisis (of which he had been one of the architects), and facilitated the decolonisation of Africa. Reconfiguring the nation's defences to meet the realities of the nuclear age, he ended National Service, strengthened the nuclear forces by acquiring Polaris, and pioneered the Nuclear Test Ban with the United States and the Soviet Union. After the Skybolt Crisis undermined the Anglo-American strategic relationship, he sought a more active role for Britain in Europe, but his unwillingness to disclose United States nuclear secrets to France contributed to a French veto of the United Kingdom's entry into the European Economic Community and independent French acquisition of nuclear weapons in 1960.[136] Near the end of his premiership, his government was rocked by the Vassall Tribunal and the Profumo affair, which to cultural conservatives and supporters of opposing parties alike seemed to symbolise moral decay of the British establishment.[137] Following his resignation, Macmillan lived out a long retirement as an elder statesman, being an active member of the House of Lords in his final years. He died in December 1986 at the age of 92.

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995[l]) was a British statesman and Labour Party politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1964 to 1970 and again from 1974 to 1976. He was Leader of the Labour Party from 1963 to 1976, Leader of the Opposition twice from 1963 to 1964 and again from 1970 to 1974, and a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1945 to 1983. Wilson is the only Labour leader to have formed administrations following four general elections.

Born in Huddersfield, Yorkshire, to a politically active middle-class family, Wilson studied a combined degree of philosophy, politics, and economics at Jesus College, Oxford. He was later an Economic History lecturer at New College, Oxford, and a research fellow at University College, Oxford. Elected to Parliament in 1945, Wilson was appointed to the Attlee government as a Parliamentary Secretary; he became Secretary for Overseas Trade in 1947, and was elevated to the Cabinet shortly thereafter as President of the Board of Trade. Following Labour's defeat at the 1955 election, Wilson joined the Shadow Cabinet as Shadow Chancellor, and was moved to the role of Shadow Foreign Secretary in 1961. When Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell died suddenly in January 1963, Wilson won the subsequent leadership election to replace him, becoming Leader of the Opposition.

Wilson led Labour to a narrow victory at the 1964 election. His first period as prime minister saw a period of low unemployment and economic prosperity; this was however hindered by significant problems with Britain's external balance of payments. His government oversaw significant societal changes, abolishing both capital punishment and theatre censorship, partially decriminalising male homosexuality in England and Wales, relaxing the divorce laws, limiting immigration, outlawing racial discrimination, and liberalising birth control and abortion law. In the midst of this programme, Wilson called a snap election in 1966, which Labour won with a much increased majority. His government armed Nigeria during the Biafran War. In 1969, he sent British troops to Northern Ireland. After losing the 1970 election to Edward Heath's Conservatives, Wilson chose to remain in the Labour leadership, and resumed the role of Leader of the Opposition for four years before leading Labour through the February 1974 election, which resulted in a hung parliament. Wilson was appointed prime minister for a second time; he called a snap election in October 1974, which gave Labour a small majority. During his second term as prime minister, Wilson oversaw the referendum that confirmed the UK's membership of the European Communities.

In March 1976, Wilson suddenly announced his resignation as prime minister. He remained in the House of Commons until retiring in 1983 when he was elevated to the House of Lords as Lord Wilson of Rievaulx. While seen by admirers as leading the Labour Party through difficult political issues with considerable skill, Wilson's reputation was low when he left office and is still disputed in historiography. Some scholars praise his unprecedented electoral success for a Labour prime minister and holistic approach to governance,[140] while others criticise his political style and handling of economic issues.[141] Several key issues which he faced while prime minister included the role of public ownership, whether Britain should seek the membership of the European Communities, and British involvement in the Vietnam War.[142] His stated ambitions of substantially improving Britain's long-term economic performance, applying technology more democratically, and reducing inequality were to some extent unfulfilled.[143]North America

[edit]Cuba

[edit]

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (/ˈkæstroʊ/ KASS-troh,[144] Latin American Spanish: [fiˈðel aleˈxandɾo ˈkastɾo ˈrus]; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 2008. Ideologically a Marxist–Leninist and Cuban nationalist, he also served as the first secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba from 1965 until 2011. Under his administration, Cuba became a one-party communist state; industry and business were nationalized, and socialist reforms were implemented throughout society.

Born in Birán, the son of a wealthy Spanish farmer, Castro adopted leftist and anti-imperialist ideas while studying law at the University of Havana. After participating in rebellions against right-wing governments in the Dominican Republic and Colombia, he planned the overthrow of Cuban president Fulgencio Batista, launching a failed attack on the Moncada Barracks in 1953. After a year's imprisonment, Castro travelled to Mexico where he formed a revolutionary group, the 26th of July Movement, with his brother, Raúl Castro, and Ernesto "Che" Guevara. Returning to Cuba, Castro took a key role in the Cuban Revolution by leading the Movement in a guerrilla war against Batista's forces from the Sierra Maestra. After Batista's overthrow in 1959, Castro assumed military and political power as Cuba's prime minister. The United States came to oppose Castro's government and unsuccessfully attempted to remove him by assassination, economic embargo, and counter-revolution, including the Bay of Pigs Invasion of 1961. Countering these threats, Castro aligned with the Soviet Union and allowed the Soviets to place nuclear weapons in Cuba, resulting in the Cuban Missile Crisis—a defining incident of the Cold War—in 1962.

Adopting a Marxist–Leninist model of development, Castro converted Cuba into a one-party, socialist state under Communist Party rule, the first in the Western Hemisphere. Policies introducing central economic planning and expanding healthcare and education were accompanied by state control of the press and the suppression of internal dissent. Abroad, Castro supported anti-imperialist revolutionary groups, backing the establishment of Marxist governments in Chile, Nicaragua, and Grenada, as well as sending troops to aid allies in the Yom Kippur, Ogaden, and Angolan Civil War. These actions, coupled with Castro's leadership of the Non-Aligned Movement from 1979 to 1983 and Cuban medical internationalism, increased Cuba's profile on the world stage. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Castro led Cuba through the economic downturn of the "Special Period", embracing environmentalist and anti-globalization ideas. In the 2000s, Castro forged alliances in the Latin American "pink tide"—namely with Hugo Chávez's Venezuela—and formed the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas. In 2006, Castro transferred his responsibilities to Vice President Raúl Castro, who was elected to the presidency by the National Assembly in 2008.

The longest-serving non-royal head of state in the 20th and 21st centuries, Castro polarized world opinion. His supporters view him as a champion of socialism and anti-imperialism whose revolutionary government advanced economic and social justice while securing Cuba's independence from American hegemony. His critics view him as a dictator whose administration oversaw human rights abuses, the exodus of many Cubans, and the impoverishment of the country's economy.United States

[edit]Government

[edit]

John F. Kennedy's tenure as the 35th president of the United States began with his inauguration on January 20, 1961, and ended with his assassination on November 22, 1963. Kennedy, a Democrat from Massachusetts, took office following his narrow victory over Republican incumbent vice president Richard Nixon in the 1960 presidential election. He was succeeded by Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Kennedy's time in office was marked by Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union and Cuba. In Cuba, a failed attempt was made in April 1961 at the Bay of Pigs to overthrow the government of Fidel Castro. In October 1962, the Kennedy administration learned that Soviet ballistic missiles had been deployed in Cuba; the resulting Cuban Missile Crisis carried a risk of nuclear war, but ended in a compromise with the Soviets publicly withdrawing their missiles from Cuba and the U.S. secretly withdrawing some missiles based in Italy and Turkey. To contain Communist expansion in Asia, Kennedy increased the number of American military advisers in South Vietnam by a factor of 18; a further escalation of the American role in the Vietnam War would take place after Kennedy's death. In Latin America, Kennedy's Alliance for Progress aimed to promote human rights and foster economic development.

In domestic politics, Kennedy had made bold proposals in his New Frontier agenda, but many of his initiatives were blocked by the conservative coalition of Northern Republicans and Southern Democrats. The failed initiatives include federal aid to education, medical care for the aged, and aid to economically depressed areas. Though initially reluctant to pursue civil rights legislation, in 1963 Kennedy proposed a major civil rights bill that ultimately became the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The economy experienced steady growth, low inflation and a drop in unemployment rates during Kennedy's tenure. Kennedy adopted Keynesian economics and proposed a tax cut bill that was passed into law as the Revenue Act of 1964. Kennedy also established the Peace Corps and promised to land an American on the Moon and return him safely to Earth, thereby intensifying the Space Race with the Soviet Union.

Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, while visiting Dallas, Texas. The Warren Commission concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in assassinating Kennedy, but the assassination gave rise to a wide array of conspiracy theories. Kennedy was the first Roman Catholic elected president, as well as the youngest candidate ever to win a U.S. presidential election. Historians and political scientists tend to rank Kennedy as an above-average president.

Lyndon B. Johnson's tenure as the 36th president of the United States began on November 22, 1963, upon the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, and ended on January 20, 1969. He had been vice president for 1,036 days when he succeeded to the presidency. Johnson, a Democrat from Texas, ran for and won a full four-year term in the 1964 presidential election, in which he defeated Republican nominee Barry Goldwater in a landslide. Johnson withdrew his bid for a second full term in the 1968 presidential election because of his low popularity. Johnson was succeeded by Republican Richard Nixon, who won the aforementioned election. His presidency marked the high tide of modern liberalism in the 20th century United States.

Johnson expanded upon the New Deal with the Great Society, a series of domestic legislative programs to help the poor and downtrodden. After taking office, he won passage of a major tax cut, the Clean Air Act, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. After the 1964 election, Johnson passed even more sweeping reforms. The Social Security Amendments of 1965 created two government-run healthcare programs, Medicare and Medicaid. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibits racial discrimination in voting, and its passage enfranchised millions of Southern African-Americans. Johnson declared a "War on Poverty" and established several programs designed to aid the impoverished. He also presided over major increases in federal funding to education and the end of a period of restrictive immigration laws.

In foreign affairs, Johnson's presidency was dominated by the Cold War and the Vietnam War. He pursued conciliatory policies with the Soviet Union, setting the stage for the détente of the 1970s. He was nonetheless committed to a policy of containment, and he escalated the U.S. presence in Vietnam in order to stop the spread of Communism in Southeast Asia during the Cold War. The number of American military personnel in Vietnam increased dramatically, from 16,000 soldiers in 1963 to over 500,000 in 1968. Growing anger with the war stimulated a large antiwar movement based especially on university campuses in the U.S. and abroad. Johnson faced further troubles when summer riots broke out in most major cities after 1965. While he began his presidency with widespread approval, public support for Johnson declined as the war dragged on and domestic unrest across the nation increased. At the same time, the New Deal coalition that had unified the Democratic Party dissolved, and Johnson's support base eroded with it. Though eligible for another term, Johnson announced in March 1968 that he would not seek renomination. His preferred successor, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, won the Democratic nomination but was narrowly defeated by Nixon in the 1968 presidential election.

Though he left office with low approval ratings, polls of historians and political scientists tend to have Johnson ranked as an above-average president. His domestic programs transformed the United States and the role of the federal government, and many of his programs remain in effect today. Johnson's handling of the Vietnam War remains broadly unpopular, but his civil rights initiatives are nearly-universally praised for their role in removing barriers to racial equality.

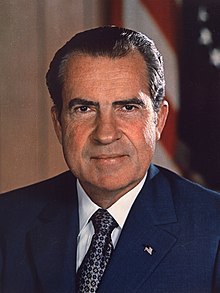

Richard Nixon's tenure as the 37th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1969, and ended when he resigned on August 9, 1974, in the face of almost certain impeachment and removal from office, the only U.S. president ever to do so. He was succeeded by Gerald Ford, whom he had appointed vice president after Spiro Agnew became embroiled in a separate corruption scandal and was forced to resign. Nixon, a prominent member of the Republican Party from California who previously served as vice president for two terms under president Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1961, took office following his narrow victory over Democratic incumbent vice president Hubert Humphrey and American Independent Party nominee George Wallace in the 1968 presidential election. Four years later, in the 1972 presidential election, he defeated Democratic nominee George McGovern, to win re-election in a landslide. Although he had built his reputation as a very active Republican campaigner, Nixon downplayed partisanship in his 1972 landslide re-election.

Nixon's primary focus while in office was on foreign affairs. He focused on détente with the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union, easing Cold War tensions with both countries. As part of this policy, Nixon signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and SALT I, two landmark arms control treaties with the Soviet Union. Nixon promulgated the Nixon Doctrine, which called for indirect assistance by the United States rather than direct U.S. commitments as seen in the ongoing Vietnam War. After extensive negotiations with North Vietnam, Nixon withdrew the last U.S. soldiers from South Vietnam in 1973, ending the military draft that same year. To prevent the possibility of further U.S. intervention in Vietnam, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution over Nixon's veto.

In domestic affairs, Nixon advocated a policy of "New Federalism", in which federal powers and responsibilities would be shifted to state governments. However, he faced a Democratic Congress that did not share his goals and, in some cases, enacted legislation over his veto. Nixon's proposed reform of federal welfare programs did not pass Congress, but Congress did adopt one aspect of his proposal in the form of Supplemental Security Income, which provides aid to low-income individuals who are aged or disabled. The Nixon administration adopted a "low profile" on school desegregation, but the administration enforced court desegregation orders and implemented the first affirmative action plan in the United States. Nixon also presided over the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and the passage of major environmental laws like the Clean Water Act, although that law was vetoed by Nixon and passed by override. Economically, the Nixon years saw the start of a period of "stagflation" that would continue into the 1970s.

Nixon was far ahead in the polls in the 1972 presidential election, but during the campaign, Nixon operatives conducted several illegal operations designed to undermine the opposition. They were exposed when the break-in of the Democratic National Committee Headquarters ended in the arrest of five burglars. This kicked off the Watergate Scandal and gave rise to a congressional investigation. Nixon denied any involvement in the break-in. However, after a tape emerged revealing that Nixon had known about the White House connection to the burglaries shortly after they occurred, the House of Representatives initiated impeachment proceedings. Facing removal by Congress, Nixon resigned from office.

Though some scholars believe that Nixon "has been excessively maligned for his faults and inadequately recognised for his virtues",[145] Nixon is generally ranked as a below average president in surveys of historians and political scientists.[146][147][148]Civil Rights leaders

[edit]

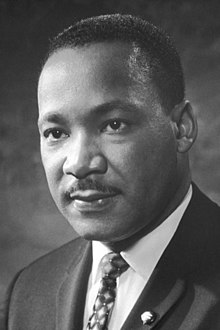

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, activist, and political philosopher who was one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. King advanced civil rights for people of color in the United States through the use of nonviolent resistance and nonviolent civil disobedience against Jim Crow laws and other forms of legalized discrimination.