Victorinus of Pettau

Victorinus of Pettau | |

|---|---|

Victorinus on a fresco in the parish church of Nova Cerkev (Slovenia) | |

| Bishop of Poetovio and Martyr | |

| Born | Likely in Roman Greece |

| Died | 303 or 304 AD Ptuj (Pettau or Poetovio) |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Feast | 2 November |

| Attributes | Palm, pontifical vestments |

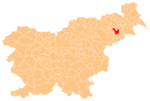

Saint Victorinus of Pettau (also Ptuj or Poetovio; Greek: Βικτωρίνος Πεταβίου; died 303 or 304) was an Early Christian ecclesiastical writer who flourished about 270, and who was martyred during the persecutions of Emperor Diocletian. A Bishop of Poetovio (modern Ptuj in Slovenia; German: Pettau) in Pannonia, Victorinus is also known as Victorinus Petavionensis or Poetovionensis.[1] Victorinus composed commentaries on various texts within the Christians' Holy Scriptures.

Life

[edit]Born probably in Roman Greece on the confines of the Eastern and Western Empires or in Poetovio with rather mixed population, due to its military character, Victorinus spoke Greek better than Latin, which explains why, in St. Jerome's opinion, his works written in the latter tongue were more remarkable for their matter than for their style.[2] Bishop of the City of Pettau, he was the first theologian to use Latin for his exegesis.

His works are mainly exegetical. Victorinus composed commentaries on various works of the Bible, including Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Isaiah, Ezekiel, Habakkuk, Ecclesiastes, the Song of Songs, Matthew, and the Apocalypse of John (Revelation). He also composed theological treatises against varieties of Christianity he considered heretical. The only works of his that survived past antiquity, however, are his Commentary on the Apocalypse[3] and the short tract On the construction of the world (De fabrica mundi).[4]

Victorinus was much influenced by Origen.[5] Jerome gives him an honorable place in his catalogue of ecclesiastical writers. Jerome occasionally cites the opinion of Victorinus (on Ecclesiastes 4:13, Ezekiel 26, and elsewhere), but considered him to have been affected by the opinions of the Chiliasts or Millenarians.[6] According to Jerome, Victorinus died a martyr in 304.[7]

By contrast to Jerome's positive reception in the late fourth and early fifth century, Victorinus's works were condemned and listed as forbidden an according to the Gelasian Decree, a 6th-century work attributed to the 5th century Pope Gelasius I; it includes a list of works compiled by heretics or used by schismatics to be rejected and avoided, and lists Victorinus's work there.[8]

Victorinus is commemorated in both the Latin Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church on 2 November. Until the 17th century he was sometimes confused with the Latin rhetorician, Victorinus Afer.

Commentary on the Apocalypse

[edit]Victorinus wrote a commentary on the Book of Revelation that was later republished in a redacted form by Jerome in the 5th century AD. An original, unredacted manuscript was found in 1918. The commentary was composed not long after the Valerian Persecution, about 260. According to Claudio Moreschini, "The interpretation is primarily allegorical, with a marked interest in arithmology."[9] Johannes Quasten writes that "It seems that he did not give a running commentary on the entire text but contented himself with a paraphrase of selected passages."[10] Victorinus interpreted Revelation 20:4-6 quite literally in a millennialist (chiliastic) fashion: as a prophecy of a forthcoming rule of the just in an Earthly paradise.[11][12]

The book is interesting to modern scholars as an example of how people in antiquity interpreted the book of Revelation. Victorinus sees the four animals singing praise to God as the Gospels, and the 24 elders seated on thrones in Revelation 4 are the 12 patriarchs of the 12 tribes of Israel and the 12 apostles. He also agrees with views that the Whore of Babylon "drunk with the blood of martyrs and saints" represents the City of Rome and its persecutions of Christians, and that The Beast described in chapter 13 represents Emperor Nero. As Nero was already dead during Victorinus's time, he believed that the later passages referred to Nero Redivivus, a monstrous revived Nero who would attack from the East with the aid of the Jews.[13] Victorinus sees the sharp two-edged sword that Christ wields with his mouth in Revelation 1 as the biblical canon, with one edge being the Old Testament and another the New Testament. He also believed that the "two witnesses" in Revelation were the prophets Elijah and another that he suspects is Jeremiah because "his death was never discovered." For Victorinus, the two witnesses (and Christ) are the only inhabitants of Paradise in the present age, as all (even Christian martyrs) are currently in Hades. However, the two witnesses will descend to Earth in the age described in Revelation to finally meet their deaths.[12]

Works

[edit]See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Erroneously, based on some bad manuscripts, also as Victorinus Pictaviensis. He was long thought to have belonged to the Diocese of Poitiers (France).

- ^ Clugnet, Léon. "St. Victorinus." The Catholic Encyclopedia Archived 21 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 10 August 2018

- ^ a b "CHURCH FATHERS: Commentary on the Apocalypse (Victorinus)". Archived from the original on 7 November 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2006.

- ^ a b "CHURCH FATHERS: On the Creation of the World (Victorinus)". Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2006.

- ^ Bardenhewer, Otto. Patrology: The Lives and Works of the Fathers of the Church, B. Herder, 1908, p. 227

- ^ "Wilson, H.A., "Victorinus", Dictionary of Christian Biography, (Henry Wace, ed.), John Murray, London, 1911". Archived from the original on 8 June 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ "Butler, Alban. "St. Victorinus, Bishop Martyr", The Lives of the Saints, 1866". Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ "The Development of the Canon of the New Testament - The Decretum Gelasianum". Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2006.

- ^ Moreschini, Claudio and Norelli, Enrico. Early Christian Greek and Latin Literature, Vol. 1, Baker Academic, 2005, ISBN 978-0801047190, p. 397

- ^ Quasten, Johannes. Patrology, Vol. 2, Thomas More Pr; (1986), ISBN 978-0870611414, p. 413

- ^ Nicklas, Tobias (2020). "Revelation and the New Testament Canon". In Koester, Craig R. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Book of Revelation. Oxford University Press. p. 364. ISBN 978-0-19-065543-3.

- ^ a b Hill, Charles E. (2020). "The Interpretation of the Book of Revelation in Early Christianity". In Koester, Craig R. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Book of Revelation. Oxford University Press. pp. 404–405. ISBN 978-0-19-065543-3.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart (12 October 2021). "Who Knew? Our Oldest Commentary on the Book of Revelation". The Bart Ehrman Blog: The History & Literature of Early Christianity. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

References

[edit] This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Victorinus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Victorinus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

[edit]- November 2 Feasts at OrthodoxWiki.org

- Works of Victorinus

- Victorinus at Catholic.org

- Victorinus at EarlyChurch.org.uk

- Victorinus at SaintPatrickDC.org Archived 1 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Victorinus at Catholic-Forum.com

- Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Latina with analytical indexes

- Works by Victorinus of Pettau at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)