Pilocarpine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Pilopine HS, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a608039 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Topical eye drops, by mouth |

| Drug class | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 0.76 hours (5 mg), 1.35 hours (10 mg)[3] |

| Excretion | urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.936 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

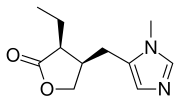

| Formula | C11H16N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 208.261 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Pilocarpine, sold under the brand name Pilopine HS among others, is a lactone alkaloid originally extracted from plants of the Pilocarpus genus.[4] It is used as a medication to reduce pressure inside the eye and treat dry mouth.[1][5] As an eye drop it is used to manage angle closure glaucoma until surgery can be performed, ocular hypertension, primary open angle glaucoma, and to constrict the pupil after dilation.[1][6][7] However, due to its side effects, it is no longer typically used for long-term management.[8] Onset of effects with the drops is typically within an hour and lasts for up to a day.[1] By mouth it is used for dry mouth as a result of Sjögren syndrome or radiation therapy.[9]

Common side effects of the eye drops include irritation of the eye, increased tearing, headache, and blurry vision.[1] Other side effects include allergic reactions and retinal detachment.[1] Use is generally not recommended during pregnancy.[10] Pilocarpine is in the miotics family of medication.[11] It works by activating cholinergic receptors of the muscarinic type which cause the trabecular meshwork to open and the aqueous humor to drain from the eye.[1]

Pilocarpine was isolated in 1874 by Hardy and Gerrard and has been used to treat glaucoma for more than 100 years.[12][13][14] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[15] It was originally made from the South American plant Pilocarpus.[12]

Medical uses

[edit]Pilocarpine stimulates the secretion of large amounts of saliva and sweat.[16] It is used to prevent or treat dry mouth, particularly in Sjögren syndrome, but also as a side effect of radiation therapy for head and neck cancer.[17]

It may be used to help differentiate Adie syndrome from other causes of unequal pupil size.[18][19]

It may be used to treat a form of dry eye called aqueous deficient dry eye (ADDE)[20]

Surgery

[edit]Pilocarpine is sometimes used immediately before certain types of corneal grafts and cataract surgery.[21][22] It is also used prior to YAG laser iridotomy. In ophthalmology, pilocarpine is also used to reduce symptomatic glare at night from lights when the patient has undergone implantation of phakic intraocular lenses; the use of pilocarpine would reduce the size of the pupils, partially relieving these symptoms.[dubious – discuss] The most common concentration for this use is pilocarpine 1%.[citation needed] Pilocarpine is shown to be just as effective as apraclonidine in preventing intraocular pressure spikes after laser trabeculoplasty.[23]

Presbyopia

[edit]In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved pilocarpine hydrochloride as an eye drop treatment for presbyopia, age-related difficulty with near-in vision. It works by causing the pupils to constrict, increasing depth of field, similar to the effect of pinhole glasses.[24][2]

Other

[edit]Pilocarpine is used to stimulate sweat glands in a sweat test to measure the concentration of chloride and sodium that is excreted in sweat. It is used to diagnose cystic fibrosis.[25]

Adverse effects

[edit]Use of pilocarpine may result in a range of adverse effects, most of them related to its non-selective action as a muscarinic receptor agonist. Pilocarpine has been known to cause excessive salivation, sweating, bronchial mucus secretion, bronchospasm, bradycardia, vasodilation, and diarrhea. Eye drops can result in brow ache and chronic use in miosis. It can also cause temporary blurred vision or darkness of vision, temporary shortsightedness, hyphema and retinal detachment.

Pharmacology

[edit]Pilocarpine is a drug that acts as a muscarinic receptor agonist. It acts on a subtype of muscarinic receptor (M3) found on the iris sphincter muscle, causing the muscle to contract - resulting in pupil constriction (miosis). Pilocarpine also acts on the ciliary muscle and causes it to contract. When the ciliary muscle contracts, it opens the trabecular meshwork through increased tension on the scleral spur. This action facilitates the rate that aqueous humor leaves the eye to decrease intraocular pressure. Paradoxically, when pilocarpine induces this ciliary muscle contraction (known as an accommodative spasm) it causes the eye's lens to thicken and move forward within the eye. This movement causes the iris (which is located immediately in front of the lens) to also move forward, narrowing the Anterior chamber angle. Narrowing of the anterior chamber angle increases the risk of increased intraocular pressure.[26]

Society and culture

[edit]Preparation

[edit]Plants in the genus Pilocarpus are the only known sources of pilocarpine, and commercial production is derived entirely from the leaves of Pilocarpus microphyllus (Maranham Jaborandi). This genus grows only in South America, and Pilocarpus microphyllus is native to several states in northern Brazil.[27]

Pilocarpine is extracted from the leaves of Pilocarpus microphyllus in a multi-step process : the sample is moistened with dilute sodium hydroxide to transform the alkaloid into its free-base form then extracted using chloroform or a suitable organic solvant. Pilocarpine can then be further purified by re-extracting the resulting solution with aqueous sulfuric acid then readjusting the pH to basic using ammonia and a final extraction by chloroform.[28][29][30]

It can also be synthesized from 2-ethyl-3-carboxy-2-butyrolactone in a 8 steps process from the acyl chloride (by treatment with thionyl chloride) via a Arndt–Eistert reaction with diazomethane then by treatment with potassium phthalimide and potassium thiocyanate.[4]

Brand names

[edit]Pilocarpine is available under several brand names such as: Diocarpine (Dioptic), Isopto Carpine (Alcon), Miocarpine (CIBA Vision), Ocusert Pilo-20 and -40 (Alza), Pilopine HS (Alcon), Salagen (MGI Pharma), Scheinpharm Pilocarpine (Schein Pharmaceutical), Timpilo (Merck Frosst), and Vuity (AbbVie).

Research

[edit]Pilocarpine is used to induce chronic epilepsy in rodents, commonly rats, as a means to study the disorder's physiology and to examine different treatments.[31][32] Smaller doses may be used to induce salivation in order to collect samples of saliva, for instance, to obtain information about IgA antibodies.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Pilocarpine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Vuity- pilocarpine hydrochloride solution/ drops". DailyMed. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ Gornitsky M, Shenouda G, Sultanem K, Katz H, Hier M, Black M, et al. (July 2004). "Double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled study of pilocarpine to salvage salivary gland function during radiotherapy of patients with head and neck cancer". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 98 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.04.009. PMID 15243470.

- ^ a b Vardanyan RS, Hruby VJ (2006). "Cholinomimetics". Synthesis of Essential Drugs. pp. 179–193. doi:10.1016/B978-044452166-8/50013-3. ISBN 978-0-444-52166-8.

- ^ Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2019 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2018. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-284-16754-2.

- ^ World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 439. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ "Glaucoma and ocular hypertension. NICE guideline 81". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. November 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

Ocular hypertension... alternative options include carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as brinzolamide or dorzolamide, a topical sympathomimetic such as apraclonidine or brimonidine tartrate, or a topical miotic such as pilocarpine, given either as monotherapy or as combination therapy.

- ^ Lusthaus J, Goldberg I (March 2019). "Current management of glaucoma". The Medical Journal of Australia. 210 (4): 180–187. doi:10.5694/mja2.50020. PMID 30767238. S2CID 73438590.

Pilocarpine is no longer routinely used for long term IOP control due to a poor side effect profile

- ^ Hamilton R (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 415. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ^ "Pilocarpine ophthalmic Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 769. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ^ a b Sneader W (2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016.

- ^ Rosin A (1991). "[Pilocarpine. A miotic of choice in the treatment of glaucoma has passed 110 years of use]". Oftalmologia (in Romanian). 35 (1): 53–55. PMID 1811739.

- ^ Holmstedt B, Wassén SH, Schultes RE (January 1979). "Jaborandi: an interdisciplinary appraisal". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(79)90014-x. PMID 397371.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "Pilocarpine". MedLinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010.

- ^ Yang WF, Liao GQ, Hakim SG, Ouyang DQ, Ringash J, Su YX (March 2016). "Is Pilocarpine Effective in Preventing Radiation-Induced Xerostomia? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 94 (3): 503–511. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.11.012. hdl:10722/229069. PMID 26867879.

- ^ Kanski JJ, Bowling B (24 March 2015). Kanski's Clinical Ophthalmology E-Book: A Systematic Approach. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 812. ISBN 978-0-7020-5574-4.

- ^ Jaanus SD, Pagano VT, Bartlett JD (1989). "Drugs Affecting the Autonomic Nervous System". Clinical Ocular Pharmacology. pp. 69–148. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7506-9322-6.50011-8. ISBN 978-0-7506-9322-6.

- ^ Mannis MJ, Holland EJ (September 2016). "Chapter 33: Dry Eye". Cornea E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-323-35758-6. OCLC 960165358.

- ^ Parker J (2017). Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK): A Review (Thesis). Leiden University. hdl:1887/50484.

- ^ Ahmed E (2010). Comprehensive Manual of Ophthalmology. JP Medical Ltd. p. 345. ISBN 978-93-5025-175-1.

- ^ Zhang L, Weizer JS, Musch DC (February 2017). "Perioperative medications for preventing temporarily increased intraocular pressure after laser trabeculoplasty". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (2): CD010746. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010746.pub2. PMC 5477062. PMID 28231380.

- ^ Grzybowski A, Ruamviboonsuk V (March 2022). "Pharmacological Treatment in Presbyopia". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 11 (5): 1385. doi:10.3390/jcm11051385. PMC 8910925. PMID 35268476.

- ^ Prasad RK (11 July 2017). Chemistry and Synthesis of Medicinal Agents: (Expanding Knowledge of Drug Chemistry). BookRix. ISBN 978-3-7438-2141-5.

- ^ Teekhasaenee C (2015). "Laser Peripheral Iridoplasty". Glaucoma. pp. 716–721. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-5193-7.00073-X. ISBN 978-0-7020-5193-7.

- ^ De Abreu IN, Sawaya AC, Eberlin MN, Mazzafera P (November–December 2005). "Production of Pilocarpine in Callus of Jaborandi (Pilocarpus microphyllus Stapf)". In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Plant. 41 (6). Society for In Vitro Biology: 806–811. doi:10.1079/IVP2005711. JSTOR 4293939. S2CID 26058596.

- ^ Avancini G, Abreu IN, Saldaña MD, Mohamed RS, Mazzafera P (May 2003). "Induction of pilocarpine formation in jaborandi leaves by salicylic acid and methyljasmonate". Phytochemistry. 63 (2): 171–175. Bibcode:2003PChem..63..171A. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00102-X. PMID 12711138.

- ^ Sawaya AC, Abreu IN, Andreazza NL, Eberlin MN, Mazzafera P (July 2008). "HPLC-ESI-MS/MS of imidazole alkaloids in Pilocarpus microphyllus". Molecules. 13 (7): 1518–1529. doi:10.3390/molecules13071518. PMC 6245396. PMID 18719522.

- ^ Schwab L (2007). "Glaucoma". In Fourth (ed.). Eye Care in Developing Nations. pp. 99–116. doi:10.1201/b15129-14 (inactive 12 November 2024). ISBN 978-1-84076-103-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Károly N (2018). Immunohistochemical investigations of the neuronal changes induced by chronic recurrent seizures in a pilocarpine rodent model of temporal lobe epilepsy (Thesis). University of Szeged. doi:10.14232/phd.9734.

- ^ Morimoto K, Fahnestock M, Racine RJ (May 2004). "Kindling and status epilepticus models of epilepsy: rewiring the brain". Progress in Neurobiology. 73 (1): 1–60. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.03.009. PMID 15193778. S2CID 36849482.