William Jackson Hooker

Sir William Jackson Hooker | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Spiridione Gambardella | |

| Born | 6 July 1785 Norwich, England, Great Britain |

| Died | 12 August 1865 (aged 80) London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, United Kingdom |

| Citizenship | British |

| Alma mater | Norwich School |

| Known for | Founding the Kew Herbarium |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Botany |

| Institutions | |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Hook. |

| Signature | |

| |

Sir William Jackson Hooker (6 July 1785 – 12 August 1865) was an English botanist and botanical illustrator, who became the first director of Kew when in 1841 it was recommended to be placed under state ownership as a botanic garden. At Kew he founded the Herbarium and enlarged the gardens and arboretum. The standard author abbreviation Hook. is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[1]

Hooker was born and educated in Norwich. An inheritance gave him the means to travel and to devote himself to the study of natural history, particularly botany. He published his account of an expedition to Iceland in 1809, even though his notes and specimens were destroyed during his voyage home. He married Maria, the eldest daughter of the Norfolk banker Dawson Turner, in 1815, afterwards living in Halesworth for 11 years, where he established a herbarium that became renowned by botanists at the time.

He held the post of Regius Professor of Botany at Glasgow University, where he worked with the botanist and lithographer Thomas Hopkirk and enjoyed the supportive friendship of Joseph Banks for his exploring, collecting and organising work. in 1841 he succeeded William Townsend Aiton as Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. He expanded the gardens at Kew, building new glasshouses, and establishing an arboretum and a museum of economic botany. Among his publications are The British Jungermanniae (1816), Flora Scotica (1821), and Species Filicum (1846–64).

He died in 1865 from complications due to a throat infection, and was buried at St Anne's Church, Kew. His son, Joseph Dalton Hooker, succeeded him as Director of Kew Gardens.

Family

[edit]Hooker's father Joseph Hooker was related to the Baring family and worked for them in Exeter and Norwich as a wool-stapler, trading in worsted and bombazine.[2][3] He was an amateur botanist who collected succulent plants,[4] and was, according to his grandson Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, "mainly a self-educated man and a fair German scholar".[5] Joseph Hooker was related to the sixteenth-century historian John Hooker, and the theologian Richard Hooker.[6]

His mother, Lydia Vincent, the daughter of James Vincent,[6] belonged to a family of Norwich worsted weavers and artists. Her cousin, William Jackson, was William Jackson Hooker's godfather.[7] Upon his death in 1789 William Jackson bequeathed his estate in Seasalter, Kent, to his godson, who inherited it when he was 21.[8] Lydia Vincent's nephew, George Vincent, was one of the most talented of the Norwich School of painters.[9]

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]William Jackson Hooker was born on 6 July 1785 at 71–77 Magdalen Street, Norwich.[10] A child named William Jacson [sic] Hooker was christened by his parents Joseph and Lydia Hooker at the nonconformist Tabernacle in Norwich on 9 November 1785.[11] He attended the Norwich Grammar School from about 1792 until his late teens,[7] but none of the school records from the period he was there have been kept, and little is known of his schooldays. He developed an interest in entomology, reading and natural history during his boyhood.[9]

In 1805, Hooker discovered a moss (now known as Buxbaumia aphylla) when out walking on Rackheath, north of Norwich.[12][13] He visited the Norwich botanist Sir James Edward Smith to consult his Linnean collections.[2] Smith advised the young Hooker to contact the botanist Dawson Turner about his discovery.[13]

Upon reaching the age of 21 he inherited an estate in Kent from his godfather.[14] His independent means allowed him to travel and develop his interest in natural history.[15]

As a young man Hooker was fascinated by the endemic birds of Norfolk and spent time studying them on the Broads and the Norfolk coast. He became skilled in drawing them and understanding their behaviour.[9] He also studied insects and, when still at school, his skills were appreciated by the Reverend William Kirby. In 1805, Kirby dedicated the Omphalapion hookerorum, a species of weevil, to him and his brother Joseph: "I am indebted to an excellent naturalist, Mr. W. J. Hooker, of Norwich, who first discovered it, for this species. Many other nondescripts have been taken by him and his brother, Mr. J. Hooker, and I name this insect after them, as a memorial of my sense of their ability and exertions in the service of my favourite department of natural history."[16]

In 1805 Hooker went to be trained in estate management at Starston Hall, Norfolk, perhaps because of the need to be able to manage his own newly acquired estates.[17] He lived there with Robert Paul, a gentleman farmer.[17] In 1806 he was introduced to Sir Joseph Banks, the president of the Royal Society. He elected to the Linnean Society of London that year.[18]

Early friends and patrons

[edit]

When a young man, Hooker gained the patronage and friendship of some of most important naturalists in eastern England, including Smith, who had founded the Linnean Society of London in 1788 and owned Carl Linnaeus's collection of plants and books, the botanist and antiquarian Dawson Turner, and Joseph Banks.[10]

In 1807, Hooker was bitten by an adder when walking near Burgh Castle and badly hurt. He was found by friends and taken to Dawson Turner's house, where he was cared for until he recovered completely from the effects of the snake's bite.[19] Once he had fully recovered, he accompanied Turner and his wife Mary on a tour of Scotland. In 1808, he again travelled to Scotland, this time accompanied by his friend William Borrer. During this journey he discovered a new species of moss, Andreaea nivalis, on Ben Nevis, which may have led to him publishing a paper Some Observations on the Genus Andreaea in 1810.[20][10]

Hooker produced the illustrations for James Edward Smith's paper Characters of Hookeria, a new Genus of Mosses, with Descriptions of Ten Species, a genus named by Smith in honour of William and his older brother Joseph. Hooker had discovered a specimen of the moss in the countryside around Holt.[21] From 1806 to 1809 he was a constant guest of Dawson Turner in Yarmouth, where he produced the illustrations for Turner's four-volume Historia Fucorum. He also spent time in London, where he took up rooms in Frith Street, near the British Museum.[16]

By 1807, Hooker had begun work as a supervising manager at a brewery at Halesworth, in partnership with Dawson Turner and Samuel Paget.[22][23] Sharing a quarter of the company, he lived in the brewery house, which had a large garden and a greenhouse in which he grew orchids.[23] The brewing venture proved to be unsuccessful, for he had no capacity for business.[24] He remained as the manager there for ten years, living at 15 Quay Street, Halesworth.[22]

Excursions abroad

[edit]

Hooker inherited enough money to be able to travel at his own expense. His first botanical expedition abroad—at the suggestion of the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, who had made a previous visit in 1772—was to Iceland, in 1809.[25][15] He sailed on the Margaret and Anne, arriving at Reykjavík in June. That month an attempt at Icelandic independence was staged by the Danish adventurer Jørgen Jørgensen.[26]

During his return voyage, the Margaret and Anne, in a dead calm, was discovered to be on fire, the result of sabotage which was afterwards found to have been planned by Danish prisoners. Hooker and the ship's company were all rescued, but the fire destroyed most of his drawings and notes.[27] Banks later offered Hooker the use of his own papers, and with these materials, along with the surviving parts of his own journal, his good memory aided him to publish an account of the island, its inhabitants and flora: his A Journal of a Tour in Iceland (1809) was privately circulated in 1811 and published two years later.[28][15]

In 1810–11, he made extensive preparations, and sacrifices which proved financially serious, with a view to travelling to Ceylon, to accompany the newly-appointed governor, Sir Robert Brownrigg.[15] He sold property inherited from his godfather, William Jackson, to raise the necessary capital for the journey. Political upheaval there led to the project being abandoned.[22][29] In 1812 he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of London.[10]

In 1813, encouraged by Sir Joseph Banks, he considered travelling to Java, but was dissuaded from the idea by friends and family.[30]

In 1814, he travelled in Europe for nine months, going to Paris with the Turners, then travelling alone to Switzerland, southern France, and Italy, where he studied plants and visited notable botanists.[31] The following year he married the eldest daughter of his friend Dawson Turner. Settling at Halesworth, he devoted himself to the formation of his herbarium, which became of worldwide renown among botanists.[15][10] In 1815, he was made a corresponding member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.[32]

Career in Glasgow

[edit]

In February 1820, Hooker was appointed as the regius professor of botany in the University of Glasgow,[33] taking over from the Scottish physician and botanist Robert Graham, and inheriting a small botanic garden that was underfunded and lacking in plants.[34] In May he was received by the University and read his inaugural thesis in Latin, written by his father-in-law, Dawson Turner.[33] Hooker was faced with the prospect of delivering lectures to students, when he had never previously taught, and was ignorant of some aspects of botany:[33] his position within the medical faculty inspired him to study for a medical degree.[35]

He soon became popular as a lecturer, his style being both clear and eloquent, and people such as local army officers came to attend them.[36][37] For 15 years he delivered a summer course on botany, required to be studied by all medical students—for the remaining months of the year he was free to study, work on his publications and his herbarium, and correspond with other botanists.[38][39]

His classroom was remarkable for having drawings of plants on display to assist the students, and their course included trips to study plants, organised by Hooker.[40] Student numbers increased from 30 in 1820 to 130 ten years later.[39] He earned £144 in his first year, which later increased,[41] but still needed to supplement his income by tutoring two boys from wealthy families, who lived with the family.[41]

His years at Glasgow were his most productive, when he was known as the most active botanist in the country.[8] In 1821 he brought out the Flora Scotica, written to be used by his botany students.[36] He was awarded a doctorate by Glasgow University in 1821.[10] He worked with the lithographer and botanist Thomas Hopkirk to establish the Royal Botanic Institution of Glasgow and to lay out and develop the Botanic Gardens. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1823.[32]

Under Hooker, the Botanic Gardens enjoyed remarkable success and became prominent in the botanic world.[42] The garden was his responsibility and he set to work developing it with the help of his extensive network of friends and acquaintances. Principal among these was Sir Joseph Banks, who promised Kew's help.[43] The botanic gardens steadily acquired new plants, often from visiting naturalists, or from students who had travelled. His work on the botanic garden resulted in experts expressing the view that "Glasgow would not suffer by comparison with any other establishment in Europe".[44]

During his professorship at Glasgow, his numerous published works included Flora Londinensis, British Flora, Flora Boreali-Americana, Icones Filicum, The Botany of Captain Beechey's Voyage to the Bering Sea, Icones Plantarum, Exotic Flora (1823–27), 13 volumes of Curtis's Botanical Magazine (from 1827), and the first seven volumes of Annals of Botany.[45] Mount Hooker, between Alberta and British Columbia, was named for him in 1827 by David Douglas.

In 1836, Hooker was made a Knight of the Royal Guelphic Order and a Knight Bachelor in recognition of his work at Glasgow and his services to botany.[10] Although officially recognised in this way, he became increasingly disillusioned with how his work was viewed by the University authorities, and by 1839 was feeling as if the "dignity of the position was stripped to one of ridicule and his work was dismissed as of no account".[46]

During his time in Glasgow, he lived, for several summers, at Invereck at the head of the Holy Loch.[47] "He seems to have devoted special attention to the vegetation of the neighbourhood," wrote John Colegate in 1868. "The result of his inquiries were published in the Rev. Dr. McKay's Statistical Account of the United Parishes of Dunoon and Kilmun."[47]

Director of Kew Gardens

[edit]The origins of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew can be traced to the merging of the royal estates of Richmond and Kew in 1772, when the garden at Kew Park formed by Henry, Lord Capell of Tewkesbury was enlarged by Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales.[48] The gardens were developed by the architect William Chambers, who built the pagoda in 1761, and by George III, who was aided by William Aiton and Sir Joseph Banks.[49] The Dutch House, now known as Kew Palace, was purchased by George III in 1781 for his children. The adjoining White House was demolished in 1802. The plant collections at Kew were first enlarged systematically by Francis Masson in 1771,[50] but had since the death of George III slowly declined.[10] In 1838, a Parliamentary review of the nation's royal gardens recommended the development of Kew as a national botanical garden.[10]

In April 1841 he was appointed as the Garden's first full time Director, on the resignation of William Townsend Aiton.[51][10] Following his appointment as director, a position he had long wished for,[10] he wrote "I feel as if I were to begin life over again", in a letter to Dawson Turner.[52] He started on an annual salary of £300, with an additional allowance of £200.[52] To Allan, who described Hooker as a man with "drive, enthusiasm and creative ability", he was eminently suited for the post, being a professional botanist, an artist, a leader with connections to others in the botanical world, who was knowledgeable about plants from Britain and those collected from around the world.[53] The curator of Kew Gardens during Hooker's period as Director was the experienced and knowledgeable botanist John Smith (1798–1888).[10]

Under Hooker's direction the gardens expanded considerably in size. Initially about 11 acres (4.5 ha) in size, they were extended to 15 acres (6.1 ha) in 1841.[54] An arboretum of 270 acres (1.1 km2) was introduced, many new glass-houses were erected, and a museum of economic botany was established.[55] In 1843 the Palm House, to a design by the architect Decimus Burton and the iron founder Richard Turner, was constructed at Kew.[56][10] The gardens and glasshouses were opened daily to the visiting public, who were allowed to wander freely there for the first time. Sir William himself wandered around during opening hours, lending his advice.[57]

He was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1862.[58]

Hooker lived with his family at West Park, a large house in which he accommodated 13 rooms of books in his library, which was seen as a public institution by the world's botanical experts, who were never turned away.[59] Among his visitors were Queen Victoria, her husband Prince Albert and their children; during 1865—the year Hooker died—the attendance had risen to 529,241.[10] Under Hooker's direction Kew became the centre of an emerging interconnected worldwide network of botanical expertise, and staff recommended by him joined expeditions or worked for botanical gardens around the world. He was invariably consulted when government questions arose about botanical matters. Newly propagated plants and sent from Kew to private and public gardens in Britain, and to botanical gardens overseas, in some cases to be developed as crops.[10]

Marriage and family

[edit]

In June 1815, he married Maria Sarah Turner,[60] the eldest daughter of Dawson Turner and Mary Palgrave. Maria was an amateur artist who collected mosses, and who with her sister Elizabeth illustrated them for her husband.[6][30] The couple toured the Lake District and across Ireland on their honeymoon, before travelling to Scotland.[61]

They had five children. William Dawson Hooker (born 1816) was a naturalist who trained as a doctor. He published Notes on Norway (1837 and 1839). He emigrated with his new wife to Jamaica to practise medicine, but died at Kingston, aged 24. Joseph Dalton Hooker (born 1817) became a botanist and was appointed the first assistant director at Kew. He served in this post for 10 years, before taking over as director from his father in 1865. The three daughters in the family were Maria (born 1819), Elizabeth (born 1820), and Mary Harriet (born 1825), who died aged sixteen.[6][10]

Death

[edit]He was engaged on the Synopsis filicum with the botanist John Gilbert Baker when he contracted a throat infection then epidemic at Kew.[62]

Works

[edit]Hooker studied mosses, liverworts, and ferns, and published a monograph on a group of liverworts, British Jungermanniae, in 1816.[10] This was succeeded by a new edition of William Curtis's Flora Londinensis, for which he wrote the descriptions (1817–1828); by a description of the Plantae cryptogamicae of Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland; by the Muscologia, a very complete account of the mosses of Britain and Ireland, prepared in conjunction with Thomas Taylor and first published in 1818;[63] and by his Musci exotici (2 volumes, 1818–1820), devoted to new foreign mosses and other cryptogamic plants.[15]

Hooker published more than 20 major botanical works over a period of 50 years, including British Jungermanniae (1816), Musci Exotici (1818–1820), Icones Filicum (1829–1831), Genera Filicum (1838) and Species Filicum (1846–1864). Other works include Flora Scotica (1821), The British Flora (1830) and Flora Borealis Americana; or, The Botany of the Northern Parts of British America (1840).[64]

With William Wilson he edited the exsiccata series Musci Americani; or, specimens of mosses, Jungermanniae, &c. collected by the late Thomas Drummond, in the Southern States of North America. Arranged and named by W. Wilson and Sir W. J. Hooker (1841).[65]

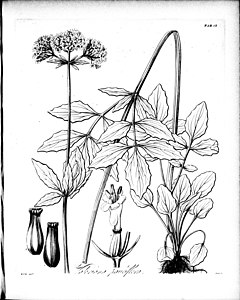

Examples

[edit]-

Bromelia aquilegia, from The Paradisus Londinensis (1805)

-

Linum hypericifilum from The Paradisus Londinensis (1807)

-

Some Observations on the Genus Andraea (1810)

-

Jungermannia Spinulosa, from Hooker's first scientific work, British Jungermanniae (1816)

-

Xanthochymus dulcis, from Curtis's Botanical Magazine (1831)

-

Valeriana pauciflora, from Flora boreali-Americana (1840)

-

Lewisia rediviva, from The Botany of Captain Beechey's Voyage (1841)

-

Gleichenia acutifolia, from Species filium (1846)

-

Abrodictyum pluma from Icones Plantarum (1854)

Plants named after William Jackson Hooker

[edit]A number plants have the Latin specific epithet of hookeri which refers to Hooker.[66] Including;

- Allium hookeri

- Alsophila hookeri

- Anthurium hookeri

- Arctostaphylos hookeri

- Dasypogon hookeri

- Drosera hookeri

- Epiphyllum hookeri

- Iris hookeri

- Kopsiopsis hookeri

- Lithops hookeri

- Lysiphyllum hookeri

- Ozothamnus hookeri

- Notholaena hookeri

- Pachyphytum hookeri

- Prosartes hookeri

- Pseudarthria hookeri

- Townsendia hookeri

References

[edit]- ^ International Plant Names Index. Hook.

- ^ a b Richardson 2002, p. 33.

- ^ Allan 1967, p. 20.

- ^ Allan 1967, p. 18.

- ^ Hooker 1902, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Lawley, Mark. "William Jackson Hooker (1785–1865)". British Bryological Society. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ a b Allan 1967, p. 26.

- ^ a b The American Journal of Science and Arts (1866). "Sir William Jackson Hooker". American Journal of Science. 41 (121): 1–10. Bibcode:1866AmJS...41....1A. doi:10.2475/ajs.s2-41.121.1. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ a b c Hooker 1902, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Fitzgerald 2020.

- ^ William Jacson Hooker [sic] in England and Wales Non-Conformist Record Indexes (RG4-8), 1588–1977, FamilySearch. (registration required)

- ^ Allan 1967, p. 17.

- ^ a b Richardson 2002, pp. 33–4.

- ^ Allan 1967, pp. 26–7.

- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm 1911, p. 674.

- ^ a b Hooker 1902, p. 11.

- ^ a b Allan 1967, p. 27.

- ^ Hooker 1902, p. 12.

- ^ Allan 1967, pp. 41–2.

- ^ Hooker, William Jackson (1810). "Some Observations in the Genus Andraea; with Descriptions of Four British Species". Transactions of the Linnean Society. 10: 381-398. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Smith, James Edward (1808). "Characters of Hookeria, a new Genus of Mosses, with Descriptions of Ten Species". Transactions of the Linnean Society. 9: 272-282. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ a b c Richardson 2002, p. 35.

- ^ a b "The Hooker Family of Halesworth". Explore Halesworth. Blythweb. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Thiselton-Dyer, William Turner (1911). "Obituary Notice of a Fellow Deceased". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character. 85 (583). The Royal Society: ii. doi:10.1098/rspb.1912.0085.

- ^ Hooker 1902, p. 14.

- ^ Hooker 1902, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Hooker 1902, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Hooker 1902, p. 18.

- ^ Hooker 1902, p. 19-20.

- ^ a b Hooker 1902, p. 20.

- ^ Hooker 1902, p. 22.

- ^ a b "Book of Members, 1780–2012: Chapter H" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. p. 250. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Hooker 1902, p. 28.

- ^ Allan 1967, pp. 75, 78.

- ^ Richardson 2002, pp. 35–6.

- ^ a b Allan 1967, p. 79.

- ^ Hooker 1902, p. 29.

- ^ Hooker 1902, p. 31.

- ^ a b Allan 1967, p. 77.

- ^ Hooker 1902, p. 30.

- ^ a b Allan 1967, p. 81.

- ^ "Glasgow Botanic Gardens Heritage Trail (page 5)". Glasgow City Council. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ Richardson 2002, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Allan 1967, pp. 79, 82–83.

- ^ Hooker 1902, pp. 40–1.

- ^ Allan 1967, p. 102.

- ^ a b Colegate's Guide to Dunoon, Kirn, and Hunter's Quay (Second edition) – John Colegate (1868), p. 35

- ^ UNESCO Advisory Body (2003). UNESCO Advisory Body Evaluation Kew (United Kingdom) No 1084 (PDF) (Report). UNESCO.

- ^ Drayton, Richard Harry (2000). Nature's Government: Science, Imperial Britain, and the 'Improvement' of the World. Yale University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-300-05976-2.

- ^ Jarrell, Richard A. (1983). "Masson, Francis". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. V (1801–1820) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Kew had formerly been a royal garden; Hooker was the first Director under its new state ownership. Turrill W.B. 1959. The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, past and present. London.

- ^ a b Allan 1967, p. 109.

- ^ Allan 1967, pp. 138–9.

- ^ Allan 1967, p. 139.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Allan 1967, p. 148.

- ^ Allan 1967, p. 140.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Allan 1967, p. 141.

- ^ William Jackson Hooker in "England, Norfolk, Parish Registers (County Record Office), 1510–1997 FamilySearch (William Jackson Hooker).

- ^ Hooker 1902, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, pp. 674–675.

- ^ Boulger, George Simonds (1898). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 55. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ "Sir William Jackson Hooker". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ "Musci Americani; or, specimens of mosses, Jungermanniae, &c. collected by the late Thomas Drummond, in the Southern States of North America. Arranged and named by W. Wilson and Sir W. J. Hooker: IndExs ExsiccataID=1032286336". IndExs – Index of Exsiccatae. Botanische Staatssammlung München. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Allen J. Coombes The A to Z of Plant Names: A Quick Reference Guide to 4000 Garden Plants, p. 244, at Google Books

Sources

[edit]This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hooker, Sir William Jackson". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 674–675.

- Allan, Mea (1967). The Hookers of Kew 1795–1911. London: M. Joseph. OCLC 459374580.

- Fitzgerald, Sylvia (2020). "Hooker, Sir William Jackson". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13699. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries)

- Hooker, Joseph Dalton (1902). "A Sketch of the Life and Labours of Sir William Jackson Hooker". In Balfour, Isaac Bayley; Scott, D.H.; Farlow, William Gilson (eds.). Annals of Botany. Vol. 16. London: Henry Froud.

- Richardson, Gudrun (2002). "A Norfolk Network within the Royal Society". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 56. The Royal Society: 27–39. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2002.0165. S2CID 144486428.

- "Sir William Jackson Hooker (1785–1865)". Kew, History & Heritage. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 28 April 2008.

External links

[edit]- Details of the books, articles, etc. written by William Jackson Hooker from the Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Details of collections in the United Kingdom containing Hooker's correspondence, notes and drawings, from the National Archives

- The Hookers' blue plaque at Kew (English Heritage)

- William Jackson Hooker at Find a Grave

- "About the Directors' Correspondence Digitisation team". Kew Botanic Gardens. 2013. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013.

- Details of Hooker's will: "Find a will". gov.uk.

- English botanical illustrators

- 1785 births

- 1865 deaths

- British pteridologists

- Botanists active in Kew Gardens

- English taxonomists

- Economic botanists

- Independent scientists

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- Academics of the University of Glasgow

- Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- People educated at Norwich School

- People from Halesworth

- Writers from Norwich

- Burials at St. Anne's Church, Kew

- 19th-century English botanists

- Scientists from Norwich

- Members of the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala