Wave–particle duality

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Quantum mechanics |

|---|

Wave-particle duality is the concept in quantum mechanics that fundamental entities of the universe, like photons and electrons, exhibit particle or wave properties according to the experimental circumstances.[1]: 59 It expresses the inability of the classical concepts such as particle or wave to fully describe the behavior of quantum objects.[2]: III:1-1 During the 19th and early 20th centuries, light was found to behave as a wave then later discovered to have a particulate behavior, whereas electrons behaved like particles in early experiments then later discovered to have wavelike behavior. The concept of duality arose to name these seeming contradictions.

History

[edit]Wave-particle duality of light

[edit]In the late 17th century, Sir Isaac Newton had advocated that light was corpuscular (particulate), but Christiaan Huygens took an opposing wave description. While Newton had favored a particle approach, he was the first to attempt to reconcile both wave and particle theories of light, and the only one in his time to consider both, thereby anticipating modern wave-particle duality.[3][4] Thomas Young's interference experiments in 1801, and François Arago's detection of the Poisson spot in 1819, validated Huygens' wave models. However, the wave model was challenged in 1901 by Planck's law for black-body radiation.[5] Max Planck heuristically derived a formula for the observed spectrum by assuming that a hypothetical electrically charged oscillator in a cavity that contained black-body radiation could only change its energy in a minimal increment, E, that was proportional to the frequency of its associated electromagnetic wave. In 1905 Einstein interpreted the photoelectric effect also with discrete energies for photons.[6] These both indicate particle behavior. Despite confirmation by various experimental observations, the photon theory (as it came to be called) remained controversial until Arthur Compton performed a series of experiments from 1922 to 1924 demonstrating the momentum of light.[7]: 211 The experimental evidence of particle-like momentum and energy seemingly contradicted the earlier work demonstrating wave-like interference of light.

Wave-particle duality of matter

[edit]The contradictory evidence from electrons arrived in the opposite order. Many experiments by J. J. Thomson,[7]: I:361 Robert Millikan,[7]: I:89 and Charles Wilson[7]: I:4 among others had shown that free electrons had particle properties, for instance, the measurement of their mass by Thomson in 1897.[8] In 1924, Louis de Broglie introduced his theory of electron waves in his PhD thesis Recherches sur la théorie des quanta.[9] He suggested that an electron around a nucleus could be thought of as being a standing wave and that electrons and all matter could be considered as waves. He merged the idea of thinking about them as particles, and of thinking of them as waves. He proposed that particles are bundles of waves (wave packets) that move with a group velocity and have an effective mass. Both of these depend upon the energy, which in turn connects to the wavevector and the relativistic formulation of Albert Einstein a few years before.

Following de Broglie's proposal of wave–particle duality of electrons, in 1925 to 1926, Erwin Schrödinger developed the wave equation of motion for electrons. This rapidly became part of what was called by Schrödinger undulatory mechanics,[10] now called the Schrödinger equation and also "wave mechanics".

In 1926, Max Born gave a talk in an Oxford meeting about using the electron diffraction experiments to confirm the wave–particle duality of electrons. In his talk, Born cited experimental data from Clinton Davisson in 1923. It happened that Davisson also attended that talk. Davisson returned to his lab in the US to switch his experimental focus to test the wave property of electrons.[11]

In 1927, the wave nature of electrons was empirically confirmed by two experiments. The Davisson–Germer experiment at Bell Labs measured electrons scattered from Ni metal surfaces.[12][13][14][15][16] George Paget Thomson and Alexander Reid at Cambridge University scattered electrons through thin metal films and observed concentric diffraction rings.[17] Alexander Reid, who was Thomson's graduate student, performed the first experiments,[18] but he died soon after in a motorcycle accident[19] and is rarely mentioned. These experiments were rapidly followed by the first non-relativistic diffraction model for electrons by Hans Bethe[20] based upon the Schrödinger equation, which is very close to how electron diffraction is now described. Significantly, Davisson and Germer noticed[15][16] that their results could not be interpreted using a Bragg's law approach as the positions were systematically different; the approach of Bethe,[20] which includes the refraction due to the average potential, yielded more accurate results. Davisson and Thomson were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1937 for experimental verification of wave property of electrons by diffraction experiments.[21] Similar crystal diffraction experiments were carried out by Otto Stern in the 1930s using beams of helium atoms and hydrogen molecules. These experiments further verified that wave behavior is not limited to electrons and is a general property of matter on a microscopic scale.

Classical waves and particles

[edit]Before proceeding further, it is critical to introduce some definitions of waves and particles both in a classical sense and in quantum mechanics. Waves and particles are two very different models for physical systems, each with an exceptionally large range of application. Classical waves obey the wave equation; they have continuous values at many points in space that vary with time; their spatial extent can vary with time due to diffraction, and they display wave interference. Physical systems exhibiting wave behavior and described by the mathematics of wave equations include water waves, seismic waves, sound waves, radio waves, and more.

Classical particles obey classical mechanics; they have some center of mass and extent; they follow trajectories characterized by positions and velocities that vary over time; in the absence of forces their trajectories are straight lines. Stars, planets, spacecraft, tennis balls, bullets, sand grains: particle models work across a huge scale. Unlike waves, particles do not exhibit interference.

Some experiments on quantum systems show wave-like interference and diffraction; some experiments show particle-like collisions.

Quantum systems obey wave equations that predict particle probability distributions. These particles are associated with discrete values called quanta for properties such as spin, electric charge and magnetic moment. These particles arrive one at time, randomly, but build up a pattern. The probability that experiments will measure particles at a point in space is the square of a complex-number valued wave. Experiments can be designed to exhibit diffraction and interference of the probability amplitude.[1] Thus statistically large numbers of the random particle appearances can display wave-like properties. Similar equations govern collective excitations called quasiparticles.

Electrons behaving as waves and particles

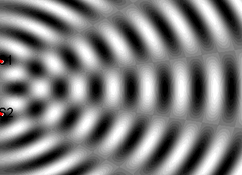

[edit]The electron double slit experiment is a textbook demonstration of wave-particle duality.[2] A modern version of the experiment is shown schematically in the figure below.

Electrons from the source hit a wall with two thin slits. A mask behind the slits can expose either one or open to expose both slits. The results for high electron intensity are shown on the right, first for each slit individually, then with both slits open. With either slit open there is a smooth intensity variation due to diffraction. When both slits are open the intensity oscillates, characteristic of wave interference.

Having observed wave behavior, now change the experiment, lowering the intensity of the electron source until only one or two are detected per second, appearing as individual particles, dots in the video. As shown in the movie clip below, the dots on the detector seem at first to be random. After some time a pattern emerges, eventually forming an alternating sequence of light and dark bands.

The experiment shows wave interference revealed a single particle at a time -- quantum mechanical electrons display both wave and particle behavior. Similar results have been shown for atoms and even large molecules.[23]

Observing photons as particles

[edit]

While electrons were thought to be particles until their wave properties were discovered; for photons it was the opposite. In 1887, Heinrich Hertz observed that when light with sufficient frequency hits a metallic surface, the surface emits cathode rays, what are now called electrons.[24]: 399 In 1902, Philipp Lenard discovered that the maximum possible energy of an ejected electron is unrelated to its intensity.[25] This observation is at odds with classical electromagnetism, which predicts that the electron's energy should be proportional to the intensity of the incident radiation.[26]: 24 In 1905, Albert Einstein suggested that the energy of the light must occur a finite number of energy quanta.[27] He postulated that electrons can receive energy from an electromagnetic field only in discrete units (quanta or photons): an amount of energy E that was related to the frequency f of the light by

where h is the Planck constant (6.626×10−34 J⋅s). Only photons of a high enough frequency (above a certain threshold value which is the work function) could knock an electron free. For example, photons of blue light had sufficient energy to free an electron from the metal he used, but photons of red light did not. One photon of light above the threshold frequency could release only one electron; the higher the frequency of a photon, the higher the kinetic energy of the emitted electron, but no amount of light below the threshold frequency could release an electron. Despite confirmation by various experimental observations, the photon theory (as it came to be called later) remained controversial until Arthur Compton performed a series of experiments from 1922 to 1924 demonstrating the momentum of light.[7]: 211

Both discrete (quantized) energies and also momentum are, classically, particle attributes. There are many other examples where photons display particle-type properties, for instance in solar sails, where sunlight could propel a space vehicle and laser cooling where the momentum is used to slow down (cool) atoms. These are a different aspect of wave-particle duality.

Which slit experiments

[edit]In a "which way" experiment, particle detectors are placed at the slits to determine which slit the electron traveled through. When these detectors are inserted, quantum mechanics predicts that the interference pattern disappears because the detected part of the electron wave has changed (loss of coherence).[2] Many similar proposals have been made and many have been converted into experiments and tried out.[28] Every single one shows the same result: as soon as electron trajectories are detected, interference disappears.

A simple example of these "which way" experiments uses a Mach–Zehnder interferometer, a device based on lasers and mirrors sketched below.[29]

A laser beam along the input port splits at a half-silvered mirror. Part of the beam continues straight, passes though a glass phase shifter, then reflects downward. The other part of the beam reflects from the first mirror then turns at another mirror. The two beams meet at a second half-silvered beam splitter.

Each output port has a camera to record the results. The two beams show interference characteristic of wave propagation. If the laser intensity is turned sufficiently low, individual dots appear on the cameras, building up the pattern as in the electron example.[29]

The first beam-splitter mirror acts like double slits, but in the interferometer case we can remove the second beam splitter. Then the beam heading down ends up in output port 1: any photon particles on this path gets counted in that port. The beam going across the top ends up on output port 2. In either case the counts will track the photon trajectories. However, as soon as the second beam splitter is removed the interference pattern disappears.[29]

See also

[edit]- Basic concepts of quantum mechanics – Non-mathematical introduction

- Complementarity (physics) – Quantum physics concept

- Einstein's thought experiments

- Interpretations of quantum mechanics

- Wheeler's delayed choice experiment – Quantum physics thought experiment

- Uncertainty principle

- Matter wave

- Corpuscular theory of light

References

[edit]- ^ a b Messiah, Albert (1966). Quantum Mechanics. North Holland, John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0486409244.

- ^ a b c Feynman, Richard P.; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew L. (2007). Quantum Mechanics. The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Vol. 3. Reading/Mass.: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-02118-9.

- ^ Arianrhod, Robyn (2012). Seduced by Logic: Émilie Du Châtelet, Mary Somerville and the Newtonian Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-19-993161-3.

- ^ Finkelstein, David Ritz (1996). Quantum Relativity. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 156, 169–170. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-60936-7. ISBN 978-3-642-64612-6.

- ^ Planck, Max (1901). "Ueber das Gesetz der Energieverteilung im Normalspectrum". Annalen der Physik (in German). 309 (3): 553–563. doi:10.1002/andp.19013090310.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (1993). The collected papers of Albert Einstein. 3: The Swiss years: writings, 1909 - 1911: [English translation]. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Pr. ISBN 978-0-691-10250-4.

- ^ a b c d e Whittaker, Edmund T. (1989). A history of the theories of aether & electricity. 2: The modern theories, 1900 - 1926 (Repr ed.). New York: Dover Publ. ISBN 978-0-486-26126-3.

- ^ Thomson, J. J. (1897). "XL. Cathode Rays". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 44 (269): 293–316. doi:10.1080/14786449708621070. ISSN 1941-5982.

- ^ de Broglie, Louis Victor. "On the Theory of Quanta" (PDF). Foundation of Louis de Broglie (English translation by A.F. Kracklauer, 2004. ed.). Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Schrödinger, E. (1926). "An Undulatory Theory of the Mechanics of Atoms and Molecules". Physical Review. 28 (6): 1049–1070. Bibcode:1926PhRv...28.1049S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.28.1049. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ Gehrenbeck, Richard K. (1978-01-01). "Electron diffraction: fifty years ago". Physics Today. 31 (1): 34–41. doi:10.1063/1.3001830. ISSN 0031-9228.

- ^ C. Davisson and L. H. Germer (1927). "The scattering of electrons by a single crystal of nickel" (PDF). Nature. 119 (2998): 558–560. Bibcode:1927Natur.119..558D. doi:10.1038/119558a0. S2CID 4104602.

- ^ Davisson, C.; Germer, L. H. (1927). "Diffraction of Electrons by a Crystal of Nickel". Physical Review. 30 (6): 705–740. Bibcode:1927PhRv...30..705D. doi:10.1103/physrev.30.705. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ Davisson, C.; Germer, L. H. (1927). "Diffraction of Electrons by a Crystal of Nickel". Physical Review. 30 (6): 705–740. Bibcode:1927PhRv...30..705D. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.30.705. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ a b Davisson, C. J.; Germer, L. H. (1928). "Reflection of Electrons by a Crystal of Nickel". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 14 (4): 317–322. Bibcode:1928PNAS...14..317D. doi:10.1073/pnas.14.4.317. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1085484. PMID 16587341.

- ^ a b Davisson, C. J.; Germer, L. H. (1928). "Reflection and Refraction of Electrons by a Crystal of Nickel". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 14 (8): 619–627. Bibcode:1928PNAS...14..619D. doi:10.1073/pnas.14.8.619. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1085652. PMID 16587378.

- ^ Thomson, G. P.; Reid, A. (1927). "Diffraction of Cathode Rays by a Thin Film". Nature. 119 (3007): 890. Bibcode:1927Natur.119Q.890T. doi:10.1038/119890a0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4122313.

- ^ Reid, Alexander (1928). "The diffraction of cathode rays by thin celluloid films". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. 119 (783): 663–667. Bibcode:1928RSPSA.119..663R. doi:10.1098/rspa.1928.0121. ISSN 0950-1207. S2CID 98311959.

- ^ Navarro, Jaume (2010). "Electron diffraction chez Thomson: early responses to quantum physics in Britain". The British Journal for the History of Science. 43 (2): 245–275. doi:10.1017/S0007087410000026. ISSN 0007-0874. S2CID 171025814.

- ^ a b Bethe, H. (1928). "Theorie der Beugung von Elektronen an Kristallen". Annalen der Physik (in German). 392 (17): 55–129. Bibcode:1928AnP...392...55B. doi:10.1002/andp.19283921704.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1937". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ a b Bach, Roger; Pope, Damian; Liou, Sy-Hwang; Batelaan, Herman (2013-03-13). "Controlled double-slit electron diffraction". New Journal of Physics. 15 (3). IOP Publishing: 033018. arXiv:1210.6243. Bibcode:2013NJPh...15c3018B. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/15/3/033018. ISSN 1367-2630. S2CID 832961.

- ^ Arndt, Markus; Hornberger, Klaus (2014). "Testing the limits of quantum mechanical superpositions". Nature Physics. 10 (4): 271–277. arXiv:1410.0270v1. Bibcode:2014NatPh..10..271A. doi:10.1038/nphys2863. ISSN 1745-2473. S2CID 56438353.

- ^ Whittaker, E. T. (1910). A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity: From the Age of Descartes to the Close of the Nineteenth Century. Longman, Green and Co.

- ^ Wheaton, Bruce R. (1978). "Philipp Lenard and the Photoelectric Effect, 1889-1911". Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences. 9: 299–322. doi:10.2307/27757381. JSTOR 27757381.

- ^ Hawking, Stephen (November 6, 2001) [November 5, 2001]. "The Universe in a Nutshell". Physics Today. 55 (4). Impey, C.D. Bantam Spectra (published April 2002): 80~. doi:10.1063/1.1480788. ISBN 978-0553802023. S2CID 120382028. Archived from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2020 – via Random House Audiobooks. Alt URL.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (1905). "Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt". Annalen der Physik. 17 (6): 132–48. Bibcode:1905AnP...322..132E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053220607, translated into English as Einstein, A. "On a Heuristic Point of View about the Creation and Conversion of Light" (PDF). The Old Quantum Theory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2009. The term "photon" was introduced in 1926.

- ^ Ma, Xiao-song; Kofler, Johannes; Zeilinger, Anton (2016-03-03). "Delayed-choice gedanken experiments and their realizations". Reviews of Modern Physics. 88 (1): 015005. arXiv:1407.2930. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.88.015005. ISSN 0034-6861. S2CID 34901303.

- ^ a b c Schneider, Mark B.; LaPuma, Indhira A. (2002-03-01). "A simple experiment for discussion of quantum interference and which-way measurement" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 70 (3): 266–271. doi:10.1119/1.1450558. ISSN 0002-9505.

External links

[edit]- R. Nave. "Wave–Particle Duality". HyperPhysics. Georgia State University, Department of Physics and Astronomy. Retrieved December 12, 2005.

- "Wave–particle duality". PhysicsQuest. American Physical Society. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- Mack, Katie. "Quantum 101 – Quantum Science Explained". Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics. Retrieved August 31, 2023.