Women in India

A woman harvesting wheat in Raisen district, Madhya Pradesh, India | |

| General Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 112 |

| Women in parliament | 14.5% |

| Women over 25 with secondary education | 41.8% [M: 53.6%] |

| Women in labour force | 27.2% [M: 78.8%] |

| Gender Inequality Index[1] | |

| Value | 0.490 (2021) |

| Rank | 122nd out of 191 |

| Global Gender Gap Index[2] | |

| Value | 0.629 (2022) |

| Rank | 135th out of 146 |

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

|

The status of women in India has been subject to many changes over the time of recorded India's history.[3] Their position in society underwent significant changes during India's ancient period, particularly in the Indo-Aryan speaking regions,[a][4][b][5][c][6] and their subordination continued to be reified well into India's early modern period.[d][7][4][5]

During the British East India Company rule (1757–1857), and the British Raj (1858–1947), measures affecting women's status, including reforms initiated by Indian reformers and colonial authorities, were enacted, including Bengal Sati Regulation, 1829, Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act, 1856, Female Infanticide Prevention Act, 1870, and Age of Consent Act, 1891. The Indian constitution prohibits discrimination based on sex and empowers the government to undertake special measures for them.[8] Women's rights under the Constitution of India mainly include equality, dignity, and freedom from discrimination; additionally, India has various statutes governing the rights of women.[9][10]

Several women have served in various senior official positions in the Indian government, including that of the President of India, the Prime Minister of India, the Speaker of the Lok Sabha. However, many women in India continue to face significant difficulties. The rates of malnutrition are exceptionally high among adolescent girls and pregnant and lactating women in India, with repercussions for children's health.[e][11] Violence against women, especially sexual violence, is a serious concern in India.[12]

Women in India during British rule

[edit]-

A little Mussulman girl, Calcutta, 1844 lithograph of a Muslim girl in India wearing Pyjamas and kurta; drawn by Emily Eden, sister of the Governor-General of India, George Eden

-

Anandibai Joshi MD Class of 1886, Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania

-

Pandita Ramabai Saraswati

During the British Raj, many reformers such as Ram Mohan Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and Jyotirao Phule fought for the betterment of women. Peary Charan Sarkar, a former student of Hindu College, Calcutta and a member of "Young Bengal", set up the first free school for girls in India in 1847 in Barasat, a suburb of Calcutta (later the school was named Kalikrishna Girls' High School). While this might suggest that there was no positive British contribution during the Raj era, that is not entirely the case. Missionaries' wives such as Martha Mault née Mead and her daughter Eliza Caldwell née Mault are rightly remembered for pioneering the education and training of girls in south India. This practice was initially met with local resistance, as it flew in the face of tradition.[citation needed] Raja Rammohan Roy's efforts led to the abolition of Sati under Governor-General William Cavendish-Bentinck in 1829. Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar's crusade for improvement in the situation of widows led to the Widow Remarriage Act of 1856. Many women reformers such as Pandita Ramabai also helped the cause of women.

Kittur Chennamma, queen of the princely state Kittur in Karnataka,[13] led an armed rebellion against the British in response to the Doctrine of lapse. Rani Lakshmi Bai, the Queen of Jhansi, led the Indian Rebellion of 1857 against the British. Rani Lakshmi Bai is celebrated in historical accounts and popular culture as a symbol of resistance[citation needed]. Begum Hazrat Mahal, the co-ruler of Awadh, was another ruler who led the revolt of 1857. She refused deals with the British and later retreated to Nepal. The Begums of Bhopal were also considered notable female rulers during this period. They were trained in martial arts. Chandramukhi Basu, Kadambini Ganguly and Anandi Gopal Joshi were some of the earliest Indian women to obtain a degree.

In 1917, the first women's delegation met the Secretary of State to demand women's political rights, supported by the Indian National Congress. The All India Women's Education Conference was held in Pune in 1927, it became a major organisation in the movement for social change.[14][15] In 1929, the Child Marriage Restraint Act was passed, stipulating fourteen as the minimum age of marriage for a girl.[14][16][full citation needed] Mahatma Gandhi, himself a victim of child marriage at the age of thirteen, later urged people to boycott child marriages and called upon young men to marry child widows.[17]

Independent India

[edit]

Women in India have made significant strides in participation across areas such as education, sports, politics, and media, though challenges remain. Indira Gandhi, who served as Prime Minister of India for an aggregate period of fifteen years, is the world's longest serving female prime minister.[18]

The Constitution of India guarantees to all Indian women equality (Article 14),[19] no discrimination by the State (Article 15(1)),[20] equality of opportunity (Article 16),[19] equal pay for equal work (Article 39(d)) and Article 42.[21][19] In addition, it allows special provisions to be made by the State in favour of women and children (Article 15(3)), renounces practices derogatory to the dignity of women (Article 51(A) (e)), and also allows for provisions to be made by the State for securing just and humane conditions of work and for maternity relief. (Article 42).[22]

Feminist activism in India gained momentum in the late 1970s. One of the first national-level issues that brought women's groups together was the Mathura rape case. The acquittal of policemen accused of raping a young girl Mathura in a police station led to country-wide protests in 1979–1980. The protest, widely covered by the national media, forced the Government to amend the Evidence Act, the Criminal Procedure Code, and the Indian Penal Code; and created a new offence, custodial rape.[22]

Since alcoholism is often associated with violence against women in India,[23] many women groups launched anti-liquor campaigns in Andhra Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and other states.[22] Many Indian Muslim women have questioned the fundamental leaders' interpretation of women's rights under the Shariat law and have criticised the triple talaq system (see below about 2017).[14]

Mary Roy won a lawsuit in 1986, against the inheritance legislation of her Keralite Syrian Christian community in the Supreme Court. The judgement ensured equal rights for Syrian Christian women with their male siblings in regard to their ancestral property.[24][25] Until then, her Syrian Christian community followed the provisions of the Travancore Succession Act of 1916 and the Cochin Succession Act, 1921, while elsewhere in India the same community followed the Indian Succession Act of 1925.[26]

In the 1990s, grants from foreign donor agencies enabled the formation of new women-oriented NGOs. Self-help groups and NGOs such as Self Employed Women's Association (SEWA) have played a major role in the advancement of women's rights in India. Many women have emerged as leaders of local movements; for example, Medha Patkar of the Narmada Bachao Andolan.

In 1991, the Kerala High Court restricted the entry of women above the age of 10 and below the age of 50 from Sabarimala Shrine, as they were of the menstruating age. However, on 28 September 2018, the Supreme Court of India lifted the ban on the entry of women. It said that discrimination against women on any grounds, even religious, is unconstitutional.[27][28]

The Government of India declared 2001 as the Year of Women's Empowerment (Swashakti).[14] The National Policy For The Empowerment Of Women was passed that same year.[29]

In 2006, the case of Imrana, a Muslim rape victim, was highlighted by the media. Imrana was raped by her father-in-law. The pronouncement of some Muslim clerics that Imrana should marry her father-in-law led to widespread protests, and finally Imrana's father-in-law was sentenced to 10 years in prison. The verdict was welcomed by many women's groups and the All India Muslim Personal Law Board.[30]

According to a 2011 poll conducted by the Thomson Reuters Foundation, India was the "fourth most dangerous country" in the world for women,[31][32] India was also noted as the worst country for women among the G20 countries,[33] however, this report has faced criticism for promoting inaccurate perceptions.[34] On 9 March 2010, one day after International Women's day, Rajya Sabha passed the Women's Reservation Bill requiring that 33% of seats in India's Parliament and state legislative bodies be reserved for women.[3] In October 2017 another poll published by Thomson Reuters Foundation found that Delhi was the fourth most dangerous megacity (total 40 in the world) for women and it was also the worst megacity in the world for women when it came to sexual violence, risk of rape and harassment.[35]

The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 is a legislative act in India that seeks to protect women from sexual harassment at their place of work. The Act came into force from 9 December 2013. The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013 introduced changes to the Indian Penal Code, making sexual harassment an expressed offence under Section 354 A, which is punishable up to three years of imprisonment and or with fine. The Amendment also introduced new sections making acts like disrobing a woman without consent, stalking and sexual acts by person in authority an offense. It also made acid attacks a specific offence with a punishment of imprisonment not less than 10 years and which could extend to life imprisonment and with fine.[36]

In 2014, an Indian family court in Mumbai ruled that a husband objecting to his wife wearing a kurta and jeans and forcing her to wear a sari amounts to cruelty inflicted by the husband and can be a ground to seek divorce.[37] The wife was thus granted a divorce on the ground of cruelty as defined under section 27(1)(d) of Special Marriage Act, 1954.[37]

On 22 August 2017, the Indian Supreme Court deemed instant triple talaq (talaq-e-biddat) unconstitutional.[38][39]

A 2018 poll by Thomson Reuters Foundation termed India as the world's most dangerous country for women.[40] The National Commission for Women[41] and the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies[42] rejected the survey for its methodology and lack of transparency.[43]

Also in 2018, the Supreme Court of India struck down a law making it a crime for a man to have sex with a married woman without the permission of her husband.[44]

Prior to November 2018, women were forbidden to climb Agasthyarkoodam. A court ruling removed the prohibition.[45]

Timeline of women's achievements in India

[edit]

The steady change in the position of women can be highlighted by looking at what has been achieved by women in the country:

- 1848: Savitribai Phule, along with her husband Jyotirao Phule, opened a school for girls in Pune, India. Savitribai Phule became the first woman teacher in India.

- 1879: John Elliot Drinkwater Bethune established the Bethune School in 1849, which developed into the Bethune College in 1879, thus becoming the first women's college in India.

- 1883: Chandramukhi Basu and Kadambini Ganguly became the first female graduates of India and the British Empire.

- 1886: Kadambini Ganguly and Anandi Gopal Joshi became the first women from India to be trained in Western medicine.

- 1898: Sister Nivedita Girls' School was inaugurated

- 1905: Suzanne RD Tata becomes the first Indian woman to drive a car.[46]

- 1916: The first women's university, SNDT Women's University, was founded on 2 June 1916 by the social reformer Dhondo Keshav Karve with just five students.

- 1917: Annie Besant became the first female president of the Indian National Congress.

- 1919: For her distinguished social service, Pandita Ramabai became the first Indian woman to be awarded the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal by the British Raj.

- 1925: Sarojini Naidu became the first Indian born female president of the Indian National Congress.

- 1927: The All India Women's Conference was founded.

- 1936: Sarla Thakral became the first Indian woman to fly an aircraft.[47][48][49]

- 1944: Asima Chatterjee became the first Indian woman to be conferred the Doctorate of Science by an Indian university.

- 1947: On 15 August 1947, following independence, Sarojini Naidu became the governor of the United Provinces, and in the process became India's first woman governor. On the same day, Amrit Kaur assumed office as the first female Cabinet minister of India in the country's first cabinet.

- Post independence:Rukmini Devi Arundale was the first ever woman in Indian History to be nominated a Rajya Sabha member. She is considered the most important revivalist in the Indian classical dance form of Bharatanatyam from its original 'sadhir' style, prevalent amongst the temple dancers, Devadasis. She also worked for the re-establishment of traditional Indian arts and crafts.

- 1951: Prem Mathur of the Deccan Airways becomes the first Indian woman commercial pilot.

- 1953: Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit became the first woman (and first Indian) president of the United Nations General Assembly

- 1959: Anna Chandy becomes the first Indian woman judge of a High Court (Kerala High Court)[50]

- 1963: Sucheta Kriplani became the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, the first woman to hold that position in any Indian state.

- 1966: Captain Durga Banerjee becomes the first Indian woman pilot of the state airline, Indian Airlines.

- 1966: Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay wins Ramon Magsaysay award for community leadership.

- 1966: Indira Gandhi becomes the first woman Prime Minister of India

- 1970: Kamaljit Sandhu becomes the first Indian woman to win a Gold in the Asian Games

- 1972: Kiran Bedi becomes the first female recruit to join the Indian Police Service.[51]

- 1978: Sheila Sri Prakash becomes the first female entrepreneur to independently start an architecture firm

- 1979: Mother Teresa wins the Nobel Peace Prize, becoming the first Indian female citizen to do so.

- 1984: On 23 May, Bachendri Pal became the first Indian woman to climb Mount Everest.

- 1986: Surekha Yadav became the first Asian woman loco-pilot or railway driver.

- 1989: Justice M. Fathima Beevi becomes the first woman judge of the Supreme Court of India.[50]

- 1991: Mumtaz M. Kazi became the first Asian woman to drive a diesel locomotive in September.[52]

- 1992: Asha Sinha becomes the First Woman Commandant in the Paramilitary forces of India when she was appointed Commandant,[53] Central Industrial Security Force in Mazagon Dock Shipbuilders Limited.

- 1992: Priya Jhingan becomes the first lady cadet to join the Indian Army (later commissioned on 6 March 1993)[54]

- 1999: On 31 October, Sonia Gandhi became the first female Leader of the Opposition (India).

- The first Indian woman to win an Olympic Medal, Karnam Malleswari, a bronze medal at the Sydney Olympics in the 69 kg weight category in Weightlifting event.

- 2007: On 25 July, Pratibha Patil became the first female President of India.

- 2009: On 4 June, Meira Kumar became the first female Speaker of Lok Sabha.

- 2011: On 20 October, Priyanka N. drove the inaugural train of the Namma Metro becoming the first female Indian metro pilot.[55]

- 2011:Mitali Madhumita made history by becoming the first woman officer to win a Sena Medal for gallantry.

- 2014: A record 7 female ministers are appointed in the Modi ministry, of whom 6 hold Cabinet rank, the highest number of female Cabinet ministers in any Indian government in history. Ministries such as Defence and External Affairs are being held by Women Ministers.[56]

- 2016: J. Jayalalithaa, became the first woman chief minister in India to rule the state consecutively 2 times by winning legislative assembly election.

- 2017: On 25 March, Tanushree Pareek became the first female combat officer commissioned by the Border Security Force.[57]

- 2018: Archana Ramasundaram of 1980 Batch became the first Woman to become the Director General of Police of a Paramilitary Force as DG, Sashastra Seema Bal.

- 2018: In February, 24 year old Flying Officer Avani Chaturvedi of the Indian Air Force became the first Indian female fighter pilot to fly solo. She flew a MiG-21 Bison, a jet aircraft with the highest recorded landing and take-off speed in the world.[58]

- 2019: On 2 December 2019, sub-lieutenant Shivangi became the first woman pilot in the Indian Navy.[59]

- 2021:A twenty-seven-year-old woman from Manipur scripted history by winning the silver medal in the Women's 49 kg Weightlifting event at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. Mirabai Chanu lifted a total of 202 kilograms.

Politics

[edit]India has one of the highest number of female politicians in the world.[citation needed] Women have held high offices in India including that of the President, Prime Minister, Speaker of the Lok Sabha and Leader of the Opposition.The Indian states Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh,[60] Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Kerala, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Orissa, Rajasthan and Tripura have implemented 50% reservation for women in PRIs.[61][62] Majority of candidates in these Panchayats are women. In 2015, 100% of elected members in Kodassery Panchayat in Kerala are women.[63] There are currently 16 female chief ministers in India as of 2020.

As of 2018, 12 out of 29 states and the union territory of Delhi have had at least one female Chief Minister.

Currently there are 81 women members and 458 male members in the Indian Parliament which equals 15.3% and 84.97% respectively.[64]

Culture

[edit]Family relations play a significant role in shaping women's status in India, influenced by cultural and regional variations. In India, the family is seen as crucially important, and in most of the country, the family unit is patrilineal. Families are usually multi-generational, with the bride moving to live with the in-laws. Families are usually hierarchical, with the elders having authority over the younger generations and men over women. The vast majority of marriages are monogamous (one husband and one wife), but both polygyny and polyandry in India have a tradition among some populations in India.[65] Weddings in India can be quite expensive. Most marriages in India are arranged.[66]

With regard to dress, a sari (a long piece of fabric draped around the body) and salwar kameez are worn by women all over India. A bindi is part of a woman's make-up. Despite common belief, the bindi on the forehead does not signify marital status; however, the Sindoor does.[67]

Rangoli (or Kolam) is a traditional art very popular among Indian women.

In 1991, the Kerala High Court restricted entry of women above the age of 10 and below the age of 50 from Sabarimala Shrine as they were of the menstruating age. On 28 September 2018, the Supreme Court of India lifted the ban on the entry of women. It said that discrimination against women on any grounds, even religious, is unconstitutional.[27][28]

Portrayal in Indian film

[edit]Over time, the Hindi film industry has evolved to portray women as independent and capable, reflecting changing societal norms, thus offering audiences a vision of gender equality. Historically, women in India have faced legal restrictions that limited their participation in various activities, and these limitations have raised concerns about the cultural practices and values of the country. Previously, these women could not apply simple and natural makeup on film characters because the law did not allow them to do it although the status quo has changed.[68] Along with the media, the Indian film industry has played an important role in driving changes in the law and improving the lives of women in India; it has sent messages to its audiences that challenge the restrictive nature of society, promoting the idea that women should have the freedom to make their own choices and live their lives on their own terms.[69]

The portrayal of women in Hindi cinema (Bollywood) has shifted over time as social norms have changed, and to include diverse representations.[70] Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge[71], or DDLJ for short, is a 1995 Bollywood film whose main female character, Simran, represented the ideal Indian woman. The film depicts her as a modest, reserved, and respectful female who remains dutiful to her family and never compromises her "purity". Yet, at the same time Simran was discouraged by her father from having a relationship with a man before marriage, especially one he did not know and of whom he did not approve. This film illustrates how women who seek romance for themselves are villainized.[72]

In contrast, films such as the 2006 Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna and 2022 Gehraiyaan explore more nonconforming female characters. In Gehraiyaan, the main characters struggle with mental illnesses, partake in infidelity, and come from broken families. The overall presence of such characters highlight how the modern Indian woman is less bound to traditional expectations and overall have been entering the workforce, been financially independent, and even sexually freed from earlier standards.[73]

Other films with nonconforming female characters include: the 2016 film Dangal, the 2022 film Mili, the 2018 film Raazi, and more.

Military and law enforcement

[edit]-

A female officer in the Indian Army briefing Russian soldiers during a joint exercise in 2015.

-

Women of the Border Security Force at the Indian Pakistan border.

The Indian Armed Forces began recruiting women to non-medical positions in 1992.[74] The Indian Army began inducting women officers in 1992.[75] The Border Security Force (BSF) began recruiting female officers in 2013. On 25 March 2017, Tanushree Pareek became the first female combat officer commissioned by the BSF.[57]

On 24 October 2015, the Indian government announced that women could serve as fighter pilots in the Indian Air Force (IAF), having previously only been permitted to fly transport aircraft and helicopters. The decision means that women are now eligible for induction in any role in the IAF.[76] In 2016, India announced a decision to allow women to take up combat roles in all sections of its army and navy.[76]

As of 2014, women made up 3% of Indian Army personnel, 2.8% of Navy personnel, and 8.5% of Air Force personnel.[77] As of 2016, women accounted for 5% of all active and reserve Indian Armed forces personnel.[76]

In 1972 Kiran Bedi became the First Lady Indian Police Service Officer and was the only woman in a batch of 80 IPS Officers, she joined the AGMUT Cadre. In 1992 Asha Sinha a 1982 Batch IPS Officer became the First Woman Commandant in the Paramilitary forces of India when she was posted as Commandant, Central Industrial Security Force in Mazagon Dock Shipbuilders Limited. Kanchan Chaudhary Bhattacharya the second Lady IPS Officer of India belonging to the 1973 Batch became the first Lady Director General of Police of a State in India when she was appointed DGP of Uttarakhand Police. In 2018 an IPS Officer Archana Ramasundram of 1980 Batch became the first Woman to become the Director General of Police of a Paramilitary Force as DG, Sashastra Seema Bal. In March 2018, Delhi Police announced that it would begin to induct women into its SWAT team.[78]

On February 17, 2020, the Supreme Court of India said that women officers in the Indian Army can get command positions at par with male officers. The court said that the government's arguments against it were discriminatory, disturbing and based on stereotype. The court also said that permanent commission to all women officers should be made available regardless of their years of service.[79] The government had earlier said that women commanders would not be acceptable to some troops.[80]

Education and economic development

[edit]Education

[edit]

Though it is sharply increasing,[83] the female literacy rate in India is less than the male literacy rate.[84] Far fewer girls than boys are enrolled in school, and many girls drop out.[22] In urban India, girls are nearly on a par with boys in terms of education. However, in rural India, girls continue to be less educated than boys. According to the National Sample Survey Data of 1997, only the states of Kerala and Mizoram have approached universal female literacy. According to scholars, the major factor behind improvements in the social and economic status of women in Kerala is literacy.[22]

Under the Non-Formal Education programme (NFE), about 40% of the NFE centres in states and 10% of the centres in UTs are exclusively reserved for women. As of 2000, about 300,000 NFE centres were catering to about 7.42 million children. About 120,000 NFE centres were exclusively for girls.[85]

According to a 1998 report by the U.S. Department of Commerce, the chief barriers to female education in India are inadequate school facilities (such as sanitary facilities), shortage of female teachers and gender bias in the curriculum (female characters being depicted as weak and helpless).[86][87]

The literacy rate is lower for women compared to men: the literacy rate is 60.6% for women, while for men it is 81.3%. The 2011 census, however, indicated a 2001–2011 decadal literacy growth of 9.2%, which is slower than the growth seen during the previous decade. There is a wide gender disparity in the literacy rate in India: effective literacy rates (age 7 and above) in 2011 were 82.14% for men and 65.46% for women. (population aged 15 or older, data from 2015).[88]

Workforce participation

[edit]

Contrary to common perception, a large percentage of women in India are actively engaged in traditional and non-traditional work.[89] Despite the large number of women involved in the workforce, the country has a female labor force participation rate of just 23%.[90] National data collection agencies accept that statistics seriously understate women's contribution as workers.[22] Reasons for these misleading statistics can be attributed to cultural biases and expectations about women's roles in society.[91][92] Additionally, more Indian women are employed in the informal economy than their male counterparts.[93] However, there are far fewer women than men in the paid workforce.

In urban India, women's workforce participation has increased, particularly in industries such as technology and services. For example, in the software industry 30% of the workforce is female.[94] These high numbers are also due to the fact that 81% of the urban female workforce is employed in the informal sector.[95] Studies have shown that higher education levels lead to higher income for urban-dwelling women.[96]

In rural India in the agriculture and allied industrial sectors, women account for as much as 89.5% of the labour force.[97] In overall farm production, women's average contribution is estimated at 55% to 66% of the total labour. According to a 1991 World Bank report, women accounted for 94% of total employment in dairy production in India.

Women constitute 51% of the total employed in forest-based small-scale enterprises.[97]

India is ahead of the world average on women in senior management.[98]

Gender pay gap

[edit]In 2017, a study by Monster Salary Index (MSI) showed the overall gender pay gap in India was 20 percent. It found that the gap was narrower in the early years of experience.[99]

While men with 0–2 years of experience earned 7.8 percent higher median wages than women, in the experience group of 6–10 years of experience, the pay gap was 15.3 percent. The pay gap becomes wider at senior level positions as the men with 11 and more years of tenure earned 25 percent higher median wages than women.

Based on the educational background, men with a bachelor's degree earned on average 16 percent higher median wages than women in years 2015, 2016 and 2017, while master's degree holders experience even higher pay gap. Men with a four- or five-year degree or the equivalent of a master's degree have on average earned 33.7 percent higher median wages than women.

India passed the Equal Remuneration Act in 1976, which prohibits discrimination in remuneration on grounds of sex. But in practice, the pay disparity still exists and is one of many lingering forms of gender inequality in the Indian workforce.[100]

Women-owned businesses

[edit]One of the most famous female business success stories, from the rural sector, is the Shri Mahila Griha Udyog Lijjat Papad. Started in 1959 by seven women in Mumbai with a seed capital of only Rs.80, it had an annual turnover of more than Rs. 800 crore (over $109 million) in 2018. It provides employment to 43,000 (in 2018) women across the country.[101]

One of the largest dairy co-operatives in the world, Amul, began by mobilizing rural women in Anand in the western state of Gujarat.[102]

Notable women in business

[edit]In 2006, Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, who founded Biocon, one of India's first biotech companies, was rated India's richest woman. Lalita D. Gupte and Kalpana Morparia were the only businesswomen in India who made the list of the Forbes World's Most Powerful Women in 2006. Gupte ran ICICI Bank, India's second-largest bank, until October 2006[103] and Morparia is CEO of JP Morgan India.[104]

Shaw remained the richest self-made woman in 2018,[105] coming in at 72nd place in terms of net worth in Forbes's annual rich list. She was the 4th and last female in the list, thereby showing that 96 of 100 the richest entities in the country continued to be male controlled directly or indirectly.

According to the ‘Kotak Wealth Hurun – Leading Wealthy Women 2018’ list, which compiled the 100 wealthiest Indian women based on their net worth as on 30 June 2018 Shaw was only one of two women, the other being Jayshree Ullal, who did not inherit their current wealth from family relatives in the top ten.[106]

However, India has a strong history of many women with inherited wealth establishing large enterprises or launching successful careers in their own rights.[107]

Land and property rights

[edit]

In most Indian families, women do not own any property in their own names, and do not get a share of parental property.[22] In India, women's property rights vary depending on religion, and tribe, and are subject to a complex mix of law and custom,[108] but in principle the move has been towards granting women equal legal rights, especially since the passing of The Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005.[109]

The Hindu personal laws of 1956 (applying to Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, and Jains) gave women rights to inheritances. However, sons had an independent share in the ancestral property, while the daughters' shares were based on the share received by their father. Hence, a father could effectively disinherit a daughter by renouncing his share of the ancestral property, but a son would continue to have a share in his own right. Additionally, married daughters, even those facing domestic abuse and harassment, had no residential rights in the ancestral home. Thanks to an amendment of the Hindu laws in 2005, women now have the same status as men.[110]

In 1986, the Supreme Court of India ruled that Shah Bano, an elderly divorced Muslim woman, was eligible for alimony. However, the decision was opposed by fundamentalist Muslim leaders, who alleged that the court was interfering in their personal law. The Union Government subsequently passed the Muslim Women's (Protection of Rights Upon Divorce) Act.[111]

Similarly, Christian women have struggled over the years for equal rights in divorce and succession. In 1994, all churches, jointly with women's organizations, drew up a draft law called the Christian Marriage and Matrimonial Causes Bill. However, the government has still not amended the relevant laws.[14] In 2014, the Law Commission of India has asked the government to modify the law to give Christian women equal property rights.[112]

Crimes against women

[edit]

Crime against women such as rape, acid attacks, dowry killings, honour killings, and the forced prostitution of young girls has been reported in India.[115][116][117] TrustLaw, a London-based news service owned by the Thomson Reuters Foundation, ranked India as the fourth most dangerous place in the world for women to live based on a poll of 213 gender experts.[118][34] Police records in India show a high incidence of crimes against women. The National Crime Records Bureau reported in 1998 that by 2010 growth in the rate of crimes against women would exceed the population growth rate.[22] Earlier, many crimes against women were not reported to police due to the social stigma attached to rape and molestation. Official statistics show a dramatic increase in the number of reported crimes against women.[22]

Acid attacks

[edit]An analyses of Indian news reports determined that 72% of cases reported from January 2002 to October 2010 included at least one female victim.[119] Sulfuric acid, nitric acid, and hydrochloric acid, the most common types of acid used in attacks, are generally cheap and widely available as a common cleaning supply.[120][121] Acid attacks against women often are done as a form of revenge and are often done by relatives or friends. The number of acid attacks has been rising in recent years.[122][123]

Child marriage

[edit]Child marriage has been traditionally prevalent in India but is not so continued in Modern India to this day. Historically, child brides would live with their parents until they reached puberty. In the past, child widows were condemned to a life of great agony, shaved heads, living in isolation, and being shunned by society.[17] Although child marriage was outlawed in 1860, it is still a common practice.[124] The Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929 is the relevant legislation in the country.

According to UNICEF's "State of the World’s Children-2009" report, 47% of India's women aged 20–24 were married before the legal age of 18, rising to 56% in rural areas.[125] The report also showed that 40% of the world's child marriages occur in India.[126]

Domestic violence

[edit]Reports suggest that domestic violence in India is a widespread issue in India, with significant social and legal implications.[127] Around 70% of women in India are victims of domestic violence, according to Renuka Chowdhury, former Union minister for Women and Child Development.[128] Domestic violence was legally addressed in the 1980s when the 1983 Criminal Law Act introduced section 498A "Husband or relative of husband of a woman subjecting her to cruelty".[129]

The National Crime Records Bureau reveal that a crime against a woman is committed every three minutes, a woman is raped every 29 minutes, a dowry death occurs every 77 minutes, and one case of cruelty committed by either the husband or relative of the husband occurs every nine minutes.[128] This occurs despite the fact that women in India are legally protected from domestic abuse under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act.[128]

In India, domestic violence toward women is considered as any type of abuse that can be considered a threat; it can also be physical, psychological, or sexual abuse to any current or former partner.[130] Domestic violence is not handled as a crime or complaint, it is seen more as a private or family matter.[130] In determining the category of a complaint, it is based on caste, class, religious bias and race which also determines whether action is to be taken or not.[130] Many studies have reported about the prevalence of the violence and have taken a criminal-justice approach, but most woman refuse to report it.[130] These women are guaranteed constitutional justice, dignity and equality but continue to refuse based on their sociocultural contexts.[130] As the women refuse to speak of the violence and find help, they are also not receiving the proper treatment.[130]

Dowry

[edit]

In 1961, the Government of India passed the Dowry Prohibition Act,[131] making dowry demands in wedding arrangements illegal. However, many cases of dowry-related domestic violence, suicides and murders have been reported. In the 1980s, numerous such cases were reported.[89]

In 1985, the Dowry Prohibition (maintenance of lists of presents to the bride and bridegroom) Rules were framed.[132] According to these rules, a signed list should be maintained of presents given at the time of the marriage to the bride and the bridegroom. The list should contain a brief description of each present, its approximate value, the name of who has given the present, and relationship to the recipient. However, such rules are rarely enforced.

A 1997 report claimed that each year at least 5,000 women in India die dowry-related deaths, and at least a dozen die each day in 'kitchen fires' thought to be intentional.[133] The term for this is "bride burning" and is criticised within India itself.

In 2011, the National Crime Records Bureau reported 8,618 dowry deaths. Unofficial estimates claim the figures are at least three times as high.[129]

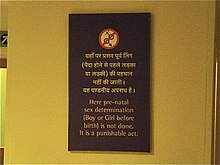

Female infanticide and sex-selective abortion

[edit]

In India, the male-female sex ratio is skewed dramatically in favour of men, the chief reason being the high number of women who die before reaching adulthood.[22] Tribal societies in India have a less skewed sex ratio than other caste groups. This is in spite of the fact that tribal communities have far lower income levels, lower literacy rates, and less adequate health facilities.[22] Many experts suggest the higher number of men in India can be attributed to female infanticides and sex-selective abortions. The sex ratio is particularly bad in the north-western area of the country, particularly in Haryana and Jammu and Kashmir.[134]

Ultrasound scanning constitutes a major leap forward in providing for the care of mother and baby, and with scanners becoming portable, these advantages have spread to rural populations. However, ultrasound scans often reveal the sex of the baby, allowing pregnant women to decide to abort female foetuses and try again later for a male child. This practice is usually considered the main reason for the change in the ratio of male to female children being born.[135]

In 1994 the Indian government passed a law forbidding women or their families from asking about the sex of the baby after an ultrasound scan (or any other test which would yield that information) and also expressly forbade doctors or any other persons from providing that information. In practice this law (like the law forbidding dowries) is widely ignored, and levels of abortion on female foetuses remain high and the sex ratio at birth keeps getting more skewed. [135]

Female infanticide (killing of infant girls) is still prevalent in some rural areas.[22] Sometimes this is infanticide by neglect, for example families may not spend money on critical medicines or withhold care from a sick girl.

Continuing abuse of the dowry tradition has been one of the main reasons for sex-selective abortions and female infanticides in India.

Honour killings

[edit]Honour killings have been reported widely in India, most frequently in the northern regions of India. This is usually motivated by a girl (or, less commonly, a boy) marrying without the family's acceptance, especially for marrying outside their caste or religion or, more particular to northwestern India, between members of the same gotra. In 2010, the Supreme Court of India issued notice in regard to honor killings to the states of Punjab, Haryana, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Himachal Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh.[136]

Accusations of witchcraft

[edit]Violence against women related to accusations of witchcraft occurs in India, particularly in parts of Northern India. Belief in the supernatural among the Indian population is strong, and lynchings for witchcraft are reported by the media.[137] In Assam and West Bengal between 2003 and 2008 there were around 750 deaths related to accusations of witchcraft.[138] Officials in the state of Chhattisgarh reported in 2008 that at least 100 women are maltreated annually as suspected witches.[139]

Rape

[edit]

Rape in India has been described by Radha Kumar as one of India's most common crimes against women[140] and by the UN’s human-rights chief as a "national problem".[141] Since the 1980s, women's rights groups lobbied for marital rape to be declared unlawful,[140] but the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013 still maintains the marital exemption by stating in its exception clause under Section 375, that: "Sexual intercourse or sexual acts by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under fifteen years of age, is not rape".[142] While per-capita reported incidents are quite low compared to other countries, even developed countries,[143][144] a new case is reported every 20 minutes.[145][146] In fact, as per the NCRB data released by the government of India in 2018, a rape is reported in India in every 15 minutes.[147]

New Delhi has one of the highest rate of rape-reports among Indian cities.[146] Sources show that rape cases in India have doubled between 1990 and 2008.[148][149]

Sexual harassment

[edit]Eve teasing is a euphemism used for sexual harassment or molestation of women by men. Many activists blame the rising incidence of sexual harassment against women on the influence of "Western culture". In 1987, The Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act was passed[150] to prohibit indecent representation of women through advertisements or in publications, writings, paintings or in any other manner.

Of the total number of crimes against women reported in 1990, half related to molestation and harassment in the workplace.[22] In 1997, in a landmark judgement[ambiguous], the Supreme Court of India took a strong stand against sexual harassment of women in the workplace. The Court also laid down detailed guidelines for prevention and redressal of grievances. The National Commission for Women subsequently elaborated these guidelines into a Code of Conduct for employers.[22] In 2013 India's top court investigated on a law graduate's allegation that she was sexually harassed by a recently retired Supreme Court judge.[151] The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act came into force in December 2013, to prevent Harassment of women at workplace.

According to a report from Human Rights Watch, despite women increasingly denunciate sexual harassment at work, they still face stigma and fear retribution as the governments promote, establish and monitor complaint committees.[152] As South Asia director at Human Rights Watch explained, “India has progressive laws to protect women from sexual abuse by bosses, colleagues, and clients, but has failed to take basic steps to enforce these laws”.[152]

A study by ActionAid UK found that 80% of women in India had experienced sexual harassment ranging from unwanted comments, being groped or assaulted. Many incidents go unreported as the victims fear being shunned by their families.[153]

Trafficking

[edit]The Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act was passed in 1956.[154]

Legislations to protect women's rights

[edit]- Guardians & Wards Act, 1890[155]

- Indian Penal Code, 1860

- Christian Marriage Act, 1872

- Indian Evidence Act, 1872[156]

- Married Women's Property Act, 1874

- Workmen's compensation Act, 1923

- Indian Successions Act, 1925

- Immoral Traffic (prevention) Act, 1956

- Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961[131]

- Commission of Sati(Prevention) Act, 1987

- Cinematograph Act, 1952

- Births, Deaths & Marriages Registration Act, 1886

- Minimum Wages Act, 1948

- Prevention of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012

- Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929

- Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application, 1937

- Indecent Representation of Women(Prevention) Act, 1986

- Special Marriage Act, 1954[157]

- Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

- Hindu Successions Act, 1956

- Foreign Marriage Act, 1969

- Family Courts Act, 1984

- Maternity Benefit Act, 1961

- Hindu Adoption & Maintenance Act, 1956

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973

- Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971

- National Commission for Women Act, 1990

- The Pre-conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Act, 1994

- Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005

- Sexual Harassment of Women at Work Place (Prevention, Prohibition & Redressal) Act, 2013[158]

- Indian Divorce Act, 1969

- Equal Remuneration Act, 1976

- Hindu Widows Remarriage Act, 1856

- Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act, 2019

Deaf/hard of hearing women

[edit]Education

[edit]As stated in earlier sections, Indian women are disadvantaged in comparison to men in many areas such as literacy skills contributing to drop out rates,[84] gender bias, and inadequate facilities.[86] Prior access to someone with a disability is the number one factor that affects how Indian teachers' attitudes toward students with disabilities,[159] so it can be challenging to find unbiased education. Deaf women face unique challenges in education, as they experience the intersection of oppression as both a woman and a Deaf person.

Education during COVID-19

[edit]In addition to the normal obstacles in accessible education, the COVID-19 pandemic added another layer of difficulty for Deaf women. Not only are they facing gender bias and having their needs put aside as women, the pandemic created new problems such as lack of face-to-face communication and masks that inhibit lipreading. A study by Rising Flame Organization found that over 90% of their sample of Deaf/DeafBlind/Hard of Hearing women in India struggled when it came to accessibility of education during the pandemic as well as other resources.[160]

Violence against Deaf women

[edit]Women and girls who have a disability, including deafness, face much more of a risk of sexual violence.[161] Deafness in particular can impair one's situational awareness and ability to quickly and effectively communicate a need for help to others (such as shouting "HELP!" to a passerby) which makes Deaf women easier targets for violence.[161]

Reporting of this violence is also extremely low due to lack of access to adequate communication - accommodations like an interpreter are rarely available in these scenarios. Even though the Indian government intended to upkeep and enforce laws regarding sexual violence - specifically mentioning women with disabilities - following civic unrest about a young woman's rape in 2013, these laws were not able to be executed effectively.[161]

Disabled women in India also struggle with problems regarding obtaining medical treatment, legal justice, compensation, and more.[161] The 2014 Guidelines and Protocols for Medico-Legal Care for Victims/Survivors of Sexual Violence by India's Ministry of Health and Family Welfare states their view about the reason disabled women often have trouble with reporting violence:

…[be]cause of the obvious barriers to communication, as well as their dependency on caretakers who may also be abusers. When they do report, their complaints are not taken seriously and the challenges they face in expressing themselves in a system that does not create an enabling environment to allow for such expression, complicates matters further.[161]

There are obvious obstacles when it comes to Deaf women reporting in the first place, such as lack of interpreters, fear of stigma, and more. However, on top of that, the justice system does not respond well when a report actually does come in.[161] Human Rights Watch even found that sometimes women and girls are denied access to accommodations if they cannot prove that they are disabled.[161] Many cases are just swept under the rug, despite legislation in place.

Organizations

[edit]There is not yet a one standardized sign language in India, so there has been much emphasis on kinship among Deaf women. They often face an intersection of oppression, being Deaf and a woman. A few organizations have crept up that are led by Deaf women to share a sense of community, learn from one another, and understand their identity as Deaf women.

Delhi Foundation of Deaf Women

[edit]The Delhi Foundation of Deaf Women (DFDW) was started in order to create space for career opportunities and to experience community and social skills among alike women that share the same identity. It hosts a number of events and social activities to promote Deaf awareness and pride in Deaf women's identities. Not only that, but it serves as a rehabilitation center for Deaf women.[162] Although it focuses primarily on Deaf women, as their needs are specific, the DFDW also helps Deaf men with some skill-building and a few Deaf men are leaders of some specific programming for the DFDW.[162]

All India Foundation of Deaf Women

[edit]The All India Foundation of Deaf Women began by filling the need of community as a club for Deaf women, but recognized that Deaf women need more structured support.[163] Since then in 1973, they have expanded into a rehabilitation center for Deaf women and other Deaf individuals. They are currently offering support, seminars, and other events.[163]

The Hyderabad Foundation Of Deaf Women has been affiliated with the All India Foundation of Deaf Women since 2014.[164] This foundation focuses on the empowerment of Deaf women in INdia and throws events like the National Cultural Festival of Deaf Women, a festival that celebrates Deaf women participating in arts, technology, and other skills.[165]

Career Opportunities

[edit]There are certain careers that, culturally, are not thought of as appropriate for Deaf people. With that in mind, the intersection of Deafness and being a woman creates a substantial societal issue when it comes to Deaf women in India finding fulfilling careers.[166]

That being said, Deafness is somewhat accepted in India and not necessarily viewed as a disability that makes a person less intelligent, which affects how employers may view Deaf candidates.[167]

Other concerns

[edit]Participation of women in social life

[edit]The degree to which women participate in public life, that is being outside the home, varies by region and background. For example, the Rajputs, a patrilineal clan inhabiting parts of India, especially the north-western area, have traditionally practiced ghunghat, and many still do to this day. In recent years however, more women have started to challenge such social norms: for instance women in rural Haryana are increasingly rejecting the ghunghat.[168] In India, most population (about two thirds)[169] is rural, and, as such, lives in tight-knit communities where it is very easy for a woman to ruin her family's 'honor' through her behavior. The concept of family honor is especially prevalent in northern India. Izzat is a concept of honor prevalent in the culture of North India and Pakistan.[170] Izzat applies to both sexes, but in different ways. Women must uphold the 'family honor' by being chaste, passive and submissive, while men must be strong, brave, and be willing and able to control the women of their families.[171] The rural areas surrounding Delhi are among the most conservative in India: it has been estimated that 30% of all honor killings of India take place in Western Uttar Pradesh,[172] while Haryana has been described as "one of India's most conservative when it comes to caste, marriage and the role of women. Deeply patriarchal, caste purity is paramount and marriages are arranged to sustain the status quo."[173]

In 2018 the Supreme Court of India lifted a decades-old ban prohibiting women between the ages of 10 and 50 from entering Sabarimala temple in Kerala. In 2019 two women entered the temple under police protection. Hindu nationalists protested the women's entry and Sreedharan Pillai, State President of the Kerala branch of the nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (of which Indian prime minister Narendra Modi is a member) described the women's entry into the temple as "a conspiracy by the atheist rulers to destroy the Hindu temples."[174] Prime Minister Modi said, "We knew that the communists do not respect Indian history, culture and spirituality but nobody imagined they will have such hatred," The shrine is dedicated to the worship of Lord Ayyappa, a celibate deity, and adherents believe the presence of women would "pollute" the site and go against the wishes of the patron deity. The two women had to go into hiding after entering the temple and were granted 24 hour police protection. One of the women was locked out of her home by her husband and had to move in to a shelter. Dozens of women seeking entry to temple have since been turned back by demonstrators.[175]

Prior to November 2018, women were forbidden to climb Agasthyarkoodam. A court ruling removed the prohibition.[45]

Health

[edit]

The average female life expectancy today in India is low compared to many countries, but it has shown gradual improvement over the years. In many families, especially rural ones, girls and women face nutritional discrimination within the family, and are anaemic and malnourished.[22] Almost half of adolescent girls are chronically malnourished.[176] In addition, poor nutrition during pregnancy often leads to birth complications.[176]

The maternal mortality in India is the 56th highest in the world.[177] 42% of births in the country are supervised in Medical Institution. In rural areas, most of women deliver with the help of women in the family, contradictory to the fact that the unprofessional or unskilled deliverer lacks the knowledge about pregnancy.[22]

Family planning

[edit]The average woman living in a rural area in India has little or no control over becoming pregnant. Women, particularly in rural areas, do not have access to safe and self-controlled methods of contraception. The public health system emphasises permanent methods like sterilisation, or long-term methods like IUDs that do not need follow-up. Sterilisation accounts for more than 75% of total contraception, with female sterilisation accounting for almost 95% of all sterilisations.[22] The contraceptive prevalence rate for 2007/2008 was estimated at 54.8%.[169]

A three-judge bench of the Supreme Court of India in Civil Appeal No. 5802 of 2022 made a ruling on 29 September 2022.[178] The ruling defined "woman" as all persons who require access to safe abortion, along with cisgender women, thus including transpersons and other gender-diverse persons as well as cisgender women.[179] The Court remarked that medical practitioners should refrain from imposing extra-legal conditions on those seeking abortion, such as obtaining the consent of the abortion seeker's family, producing documentary proofs, or judicial authorization, and that only the abortion seeker's consent was material, unless she was a minor or mentally ill.[180] It also stated that "every pregnant woman has the intrinsic right to choose to undergo or not to undergo abortion without any consent or authorization from a third party"[181] and that a woman is the only and "ultimate decision-maker on the question of whether she wants to undergo an abortion."[182] On the topic of the difference between the gestation period considered legal for married and unmarried women—24 weeks for the former and 20 weeks for the latter—the Court ruled that the distinction was discriminatory, artificial, unsustainable and in violation of Article 14 of the Constitution of India,[183] and that "all women are entitled to the benefit of safe and legal abortion."[184] On the subject of pregnancies resulting from marital rape, the Court ruled that women can seek an abortion in the term of 20 to 24 weeks under the ambit of "survivors of sexual assault or rape".[185]

Women from lower castes

[edit]Lower caste women in India have seen significant improvement in their status. Educated and financially well-off Dalit women used politics to achieve status, however, the number of Dalit women who were involved in politics later declined due to increasing income and educational levels.[186] The status of Dalit women within households is also noted to have been improved.[187]

Sex ratios

[edit]

India has a highly skewed sex ratio, which is attributed to sex-selective abortion and female infanticide affecting approximately one million female babies per year.[188] In, 2011, government stated India was missing three million girls and there are now 48 less girls per 1,000 boys.[189] Despite this, the government has taken further steps to improve the ratio, and the ratio is reported to have been improved in recent years.[190]

The number of missing women totaled 100 million across the world.[191] The male-to-female ratio is high in favor toward men in developing countries in Asia, including India, than that of areas such as North America. Along with abortion, the high ratio of men in India is a result of sex selection, where physicians are given the opportunity to incorrectly[clarification needed] determine the sex of a child during the ultrasound.[192] India currently has a problem known as the "missing women", but it has been present for quite some time.[timeframe?] The female mortality in 2001 was 107.43.[193] The deaths of these "missing women" were attributed to the death history rate of women in India starting in 1901.

The gap between the two gender titles is a direct response to the gender bias within India. Men and women in India have unequal health and education rights. Male education and health are more of a priority, so women's death rates are increasing.[193] The argument continues[according to whom?] that a lack of independence that women are not allowed to have is a large contributor to these fatalities. Women in India have a high fertility rate and get married at a young age. Those who are given more opportunity and rights are more likely to live longer and contribute to the economy rather than that of a woman expected to serve as a wife starting at a young age and continuing the same responsibilities for the rest of her life.[editorializing] As women continue to "disappear," the sex ratio turns its favor toward men. In turn, this offsets reproduction and does not allow for a controlled reproductive trend. While the excess mortality of women is relatively high, it cannot be blamed completely for the unequal sex ratio in India.[neutrality is disputed] However, it is a large contributor considering the precedence that Indian men have over women.

Sanitation

[edit]In rural areas, schools have been reported to have gained the improved sanitation facility.[194] Given the existing socio-cultural norms and situation of sanitation in schools, girl students are forced not to relieve themselves in the open unlike boys.[195] Lack of facilities in home forces women to wait for the night to relieve themselves and avoid being seen by others.[196] Access to sanitation in Bihar has been discussed. According to an estimate from 2013, about 85% of the rural households in Bihar have no access to a toilet; and this creates a dangerous situation for women and girls who are followed, attacked and raped in the fields.[197]

In 2011 a "Right to Pee" (as called by the media) campaign began in Mumbai, India's largest city.[198] Women, but not men, have to pay to urinate in Mumbai, despite regulations against this practice. Women have also been sexually assaulted while urinating in fields.[198] Thus, activists have collected more than 50,000 signatures supporting their demands that the local government stop charging women to urinate, build more toilets, keep them clean, provide sanitary napkins and a trash can, and hire female attendants.[198] In response, city officials have agreed to build hundreds of public toilets for women in Mumbai, and some local legislators are now promising to build toilets for women in every one of their districts.[198]

See also

[edit]- Welfare schemes for women in India

- Women in Indian Armed Forces

- Gender inequality in India

- Women's suffrage in India

- Menstrual taboo

- Rape in India

- Social issues in India

- Women in agriculture in India

- Gender pay gap in India

- Women's rights in Jammu and Kashmir

- Women in Hinduism

- Women in Sikhism

- Women's Reservation Bill

- National Commission for Women

- Ministry of Women and Child Development

- Centre for Equality and Inclusion

- Women's Rights Are Human Rights

Lists of Indian women by profession:

- Category:Lists of Indian women

- List of female chief ministers in India

- Dancers

- Film actresses

- Writers

- Sportswomen

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Therefore, by the time of the Mauryan Empire the position of women in mainstream Indo-Aryan society seems to have deteriorated. Customs such as child marriage and dowry were becoming entrenched; and a young women’s purpose in life was to provide sons for the male lineage into which she married. To quote the Arthashāstra: ‘wives are there for having sons’. Practices such as female infanticide and the neglect of young girls were also developing at this time. Further, due to the increasingly hierarchical nature of the society, marriage was becoming a mere institution for childbearing and the formalization of relationships between groups. In turn, this may have contributed to the growth of increasingly instrumental attitudes towards women and girls (who moved home at marriage). It is important to note that, in all likelihood, these developments did not affect people living in large parts of the subcontinent—such as those in the south, and tribal communities inhabiting the forested hill and plateau areas of central and eastern India. That said, these deleterious features have continued to blight Indo-Aryan speaking areas of the subcontinent until the present day.[4]"

- ^ "Darkness can be said to have pervaded one aspect of society during the inter-imperial centuries: the degradation of women. In Hinduism, the monastic tradition was not institutionalized as it was in the heterodoxies of Buddhism and Jainism, where it was considered the only true path to spiritual liberation. (p. 88) Instead, Hindu men of upper castes, passed through several stages of life: that of initiate, when those of the twice-born castes received the sacred thread; that of student, when the upper castes studied the Vedas; that of the married man, when they became householders; ... Since the Hindu man was enjoined to take a wife at the appropriate period of life, the roles and nature of women presented some difficulty. Unlike the monastic ascetic, the Hindu man was exhorted to have sons, and could not altogether avoid either women or sexuality. ... Manu approved of child brides, considering a girl of eight suitable for a man of twenty-four, and one of twelve appropriate for a man of thirty.(p. 89) If there was no dowry, or if the groom’s family paid that of the bride, the marriage was ranked lower. In this ranking lay the seeds of the curse of dowry that has become a major social problem in modern India, among all castes, classes and even religions. (p. 90) ... the widow’s head was shaved, she was expected to sleep on the ground, eat one meal a day, do the most menial tasks, wear only the plainest, meanest garments, and no ornaments. She was excluded from all festivals and celebrations, since she was considered inauspicious to all but her own children. This penitential life was enjoined because the widow could never quite escape the suspicion that she was in some way responsible for her husband’s premature demise. ... The positions taken and the practices discussed by Manu and the other commentators and writers of Dharmashastra are not quaint relics of the distant past, but alive and recurrent in India today – as the attempts to revive the custom of sati (widow immolation) in recent decades has shown."[5]

- ^ "The legal rights, as well as the ideal images, of women were increasingly circumscribed during the Gupta era. The Laws of Manu, compiled from about 200 to 400 C.E., came to be the most prominent evidence that this era was not necessarily a golden age for women. Through a combination of legal injunctions and moral prescriptions, women were firmly tied to the patriarchal family, ... Thus the Laws of Manu severely reduced the property rights of women, recommended a significant difference in ages between husband and wife and the relatively early marriage of women, and banned widow remarriage. Manu's preoccupation with chastity reflected possibly a growing concern for the maintenance of inheritance rights in the male line, a fear of women undermining the increasingly rigid caste divisions, and a growing emphasis on male asceticism as a higher spiritual calling."[6]

- ^ "In regions where social life was not influenced significantly by great warrior lineages – on the fringes of Mughal power, in the north-eastern mountains, the southern peninsula, Sri Lanka, and Nepal – marriage customs tend to elaborate local family ties, enhancing local identities. Women typically marry in or near their natal village. Marriage to kin is preferred. Female seclusion (pardah) is rare and rates of female participation in higher education and wage labour are normal. Women commonly work in public in fields, in shops, and in offices. Unmarried women often walk the streets and use public transport alone or with friends, both male and female. By contrast, in regions ruled by great warrior clans – in the heartlands of Mughal power across Afghanistan, Pakistan, Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and east across Bangladesh – extensive marriage networks are typical and the regional rank of families is critical. Marriage is normally forbidden within villages and to close kin. Families prefer women to marry at some distance from the natal village, and more so in high-status families. Pardah is widely practised, and as a result, women’s participation in education and wage labour is low. A woman’s place is definitely at home, where her virtue is the family honour. It is thus less common to see women working in public or travelling without male kin."[7]

- ^ "Reports of National Health & Family Survey, United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, and WHO have highlighted that rates of malnutrition among adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women, and children are alarmingly high in India. Factors responsible for malnutrition in the country include the mother’s nutritional status, lactation behaviour, women’s education, and sanitation. These affect children in several ways including stunting, childhood illness, and retarded growth."[11]

References

[edit]- ^ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORTS. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ "Global Gender Gap Report 2022" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Rajya Sabha passes Women's Reservation Bill". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 10 March 2010. Archived from the original on 14 March 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Dyson, Tim (2018), A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day, Oxford University Press, p. 20, ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8

- ^ a b c Stein, Burton (2010), A History of India, John Wiley & Sons, p. 90, ISBN 978-1-4443-2351-1

- ^ a b Ramusack, Barbara N. (1999), "Women in South Asia", in Barbara N. Ramusack, Sharon L. Sievers (ed.), Women in Asia: Restoring Women to History, Indiana University Press, pp. 27–29, ISBN 0-253-21267-7, archived from the original on 10 October 2023, retrieved 15 August 2019

- ^ a b Ludden, David (2013), India and South Asia: A Short History, Oneworld Publications, p. 101, ISBN 978-1-78074-108-6

- ^ Salini, S. (2017). "Protection Of Women Under Indian Constitution". Buddy-Mantra. Archived from the original on 1 October 2023. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ Parihar, Lalita Dhar (2011). Women and law: from impoverishment to empowerment. Lucknow: Eastern Book Company. ISBN 9789350280591.

- ^ Rao, Mamta (2008). Law relating to women and children (3rd ed.). Lucknow: Eastern Book Co. ISBN 9788170121329.

...women and the protection provided under various criminal, personal and labour laws in India

- ^ a b Narayan, Jitendra; John, Denny; Ramadas, Nirupama (2018). "Malnutrition in India: status and government initiatives". Journal of Public Health Policy. 40 (1): 126–141. doi:10.1057/s41271-018-0149-5. ISSN 0197-5897. PMID 30353132. S2CID 53032234.

- ^ India + Rape and Sexual Assault, Guardian, retrieved 15 August 2019

- ^ Saraswati English Plus. New Saraswati House. p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e Madhok, Sujata. "Women: Background & Perspective". InfoChange India. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ Nelasco, Shobana (2010). Status of women in India. New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications. p. 11. ISBN 9788184502466.

- ^ Ambassador of Hindu Muslim Unity, Ian Bryant Wells

- ^ a b Kamat, Jyotsana (19 December 2006). "Gandhi and status of women (blog)". kamat.com. Kamat's Potpourri. Archived from the original on 9 December 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ "Oxford University's famous south Asian graduates (Indira Gandhi)". BBC News. 5 May 2010. Archived from the original on 19 May 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ a b c "Women related law:- All compiled – Into Legal World". Into Legal World. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ "Women related law:- All compiled – Into Legal World". Into Legal World. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ "Women Rights in India: Constitutional Rights and Legal Rights". EduGeneral. 3 August 2017. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Menon-Sen, Kalyani; Kumar, A.K. Shiva (2001). "Women in India: How Free? How Equal?". United Nations. Archived from the original on 11 September 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ Velkoff, Victoria A.; Adlakha, Arjun (October 1998). Women of the World: Women's Health in India (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ Iype, George. "Ammu may have some similarities to me, but she is not Mary Roy". rediff. Archived from the original on 11 February 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ George Jacob (29 May 2006). "Bank seeks possession of property in Mary Roy case". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 31 May 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Jacob, George (20 October 2010). "Final decree in Mary Roy case executed". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ a b "Supreme Court upholds the right of women of all ages to worship at Sabarimala | Live updates". The Hindu. 28 September 2018. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ a b "Women Of All Ages Can Enter Sabarimala Temple, Says Top Court, Ending Ban". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "National policy for the empowerment of women". wcd.nic.in. Ministry of Women and Child Development. 2001. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ Rao, M.V.R. (27 October 2006). "Imrana: father-in-law gets 10 yrs, Muslim board applauds order". southasia.oneworld.net. OneWorld South Asia. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ Chowdhury, Kavita (16 June 2011). "India is fourth most dangerous place in the world for women: Poll". India Today. New Delhi: Living Media. Archived from the original on 15 February 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (15 June 2011). "Afghanistan worst place in the world for women, but InIn 2017dia in top five". The Guardian | World news. London. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ Baldwin, Katherine (13 June 2012). "Canada best G20 country to be a woman, India worst – TrustLaw poll". Thomson Reuters Foundation News.

- ^ a b "India ranked worst G20 country for women". feministsindia.com. FeministsIndia. 13 June 2012. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ Canton, Naomi (16 October 2017). "Sexual attacks: Delhi worst in world, says poll". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ "Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013" (PDF). Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ a b PTI (28 June 2014). "Wife's jeans ban is grounds for divorce, India court rules". GulfNews.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ "Supreme Court scraps instant triple talaq: Here's what you should know about the practice". 22 August 2017. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ "Small step, no giant leap". 23 August 2017. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ "Survey terms India most dangerous country for women". Dawn. 26 June 2018. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ Bureau, Zee Media (27 June 2018). "National Commission for Women rejects survey that said India is most dangerous place for women". Zee News.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Is India really the most dangerous country for women?". BBC News. BBC. 28 June 2018. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ Balkrishna Chayan Kundu (17 September 2018). "Fact Check: Is India really no country for women?". India Today. Archived from the original on 18 November 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Biswas, Soutik (27 September 2018). "Adultery no longer a crime in India". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ a b Regan, Helen (18 January 2019). "Indian woman is first to climb Kerala mountain reserved for men". CNN. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ "Mumbai Police History". mumbaipolice.maharashtra.gov.in. Mumbai Police. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ Centennial Team. "Sarla Thakral". centennialofwomenpilots.com. Institute for Women Of Aviation Worldwide (iWOAW). Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "72. Sarla Thakral : Women's Day: Top 100 coolest women of all time". IBN Live. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "Down memory lane: First woman pilot recounts life story" (Video). NDTV. 13 August 2006. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Former Chief Justices / Judges". highcourtofkerala.nic.in. High Court of Kerala. Archived from the original on 14 December 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ "Kiran Bedi of India appointed civilian police adviser". un.org. United Nations. 10 January 2003. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ "Asia's first woman to drive a diesel train is an Indian". Rediff. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ Salam, Shawrina (7 December 2021). "6 Indian Women In Sports Who Made Headlines In 2021". Feminism In India. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ Ramamurthi, Divya (23 February 2003). "Always 001, Army's first lady cadet looks back". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 30 March 2007.

- ^ "Young woman loco pilot has the ride of her life". The Hindu. 22 October 2011. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ "Women Cabinet Ministers in India". 1 July 2014. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ a b "First woman combat officer commissioned in BSF after 51 years". The Indian Express. 25 March 2017. Archived from the original on 4 September 2024. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "9 facts about Avani Chaturvedi that will inspire you". Times of India. 22 February 2018. Archived from the original on 4 September 2024. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ Kumar, Ajay (3 December 2019). "First Navy Pilot: Bihar girl first woman pilot of Indian Navy". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 4 September 2024. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "50pc reservation for women in panchayats". Oneindia News. 27 August 2009. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ "50% reservation for women in AP, Bihar Panchayats". Sify News. 25 November 2011. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ "Mayor Malayalam News". Mathrubhumi (in Malayalam). 26 November 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ "Woman's Malayalam News". Mathrubhumi (in Malayalam). 24 November 2015. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ "Members : Lok Sabha". 164.100.47.194. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "India: Family". countrystudies.us. Country Studies. Archived from the original on 4 September 2024. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ "Most Indians still prefer arranged marriages". The Times of India. 2 September 2014. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ "Hindu Red Dot". Snopes.com. 31 December 1998. Archived from the original on 4 September 2024. Retrieved 3 April 2012.