Works of art in The Aesthetics of Resistance

The Works of art in The Aesthetics of Resistance are those included in Peter Weiss' novel The Aesthetics of Resistance. They form a kind of musée imaginaire (imagined museum) with more than a hundred named artists and just as many artworks, mainly of the visual arts and literature, but also of music and the performing arts.[1] Peter Weiss wrote the three-volume novel, which runs to around 1000 pages, between 1971 and 1981. The plot is set between 1936 and 1945, and is located in Nazi Berlin, Spain during the civil war, Paris before the World War II and Stockholm as one of the places of refuge for the German exiles. The characters are based on real personalities, the main protagonists organising themselves in the resistance group known as the Red Orchestra. Representations of artists, works of art, their contexts and backgrounds are included in the plot line and form a web of mutual interconnections. The reception takes place in multi-layered reflections by the protagonists of the novel, through the reference to historical and political events, to mythological set pieces, to artists' biographies, to dream images or in critical questioning.

List of artworks

[edit]The following list contains about one hundred works of art in the visual arts, literature and music that are extensively discussed, named, enumerated or included in Aesthetics of Resistance. In addition, motifs of mythology as well as events and places directly related to Peter Weiss' reception of art are included in the list. The artworks and backgrounds are largely arranged in the order in which they appear in the book. Exceptions are motifs that receive a more detailed description after a brief mention on later pages. The hundred or so artists featured in the novel can be found in the list of artists in Aesthetics of Resistance.

By clicking on the arrow in the table headings, the list can be sorted differently; a detailed description of the sorting options can be found at the end of the table.

| Illustration / Chronology | Artist / Origin | Work / Classification | Entry in the novel |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ancient | Pergamon Altar first half of the 2nd century BC. Berlin, Pergamon Museum Building

|

The description of the Pergamon Altar and the gigantomachy it depicts forms the introduction to the novel. The protagonists question the viewpoint of the observer: they see the victorious gods as symbols of the rulers who had the monumental work of art created by exploited people, war is stylised into a myth.[2] They themselves identify with the defeated children of the Gaia and discuss the role of Heracles.[3] This is followed by reflections on the significance of the Pergamon Altar in the history of Pergamon, the excavation of the altar and the transfer of the art treasures to Germany.[4] One conclusion of the first-person narrator is

Further lines of thought on the Pergamon Altar are taken up in the course of the novel and conclude the work as a whole with the last chapter, so that this motif frames the novel, as it were.[6][7] |

|

Greek mythology | Gigantomachy

Mythology

|

The depiction and reception of the Gigantomachy occupies a central space with the description of the Pergamon Altar in the introduction and is taken up in detail several times in the course of the novel. It stands as a symbol for the struggle of the resisters against fascism.

|

|

Greek mythology | Gaia

Mythology

The goddess Gaia is the earth mother or personified earth of Greek mythology.

|

The motif of the Gaia becomes the figure of identification for the protagonists: The image is taken up again in Book 3, when the first-person narrator recognises the face of the Gaia on his sick mother.[9] |

|

Greek mythology | Heracles

Mythology

|

The motif of Herakles is a central, recurring simile and stands as a critically questioned symbol for the oppressed or the working class. The absence of his figure from the Pergamon Altar leads to the recurring element of the quest for Heracles, which comes to a close at the end of the novel. |

|

Ancient | Market Gate of Miletus, around 120 BC Pergamon Museum, Building

|

The protagonists also visit this structure during their visit to the Pergamon Museum. The story of the city of Miletus is taken up again elsewhere in the novel in the portrayal of antiquity as a wealth-accumulating slaveholding society. |

|

Antiquity | Ishtar Gate

6th century BC

Berlin, Pergamon Museum Building

|

During the visit to the Pergamon Museum, the protagonists walk along this building, going down a few more centuries. |

|

Paul Otto | Wilhelm von Humboldt Monument, 1883 marble statue Fine arts Monument to Wilhelm von Humboldt (1765-1835), polymath who is regarded as a pioneer in cultural studies and education.

|

As they walk through Berlin, the protagonists point to "the Humboldt brothers enthroned high in armchairs with griffin's feet, poring over open books". |

|

Reinhold Begas | Alexander von Humboldt Monument 1883, marble statue Fine arts Monument to Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), natural scientist, who was also called "world scientist" because of his erudition and extensive travels.

|

As they walk through Berlin, the protagonists point to

|

|

Arthur Rimbaud | A Season in Hell,1873 Collection of poems Literature

|

In the novel's questioning of what possibilities the poorly educated working class has to appropriate culture, the protagonists discuss the intelligibility of language in relation to its banalisation, using Rimbaud as an example:

The work is mentioned once more in the second volume, when the first-person narrator seeks to get to know the city of Paris in the footsteps of various artists. |

|

Ilya Repin | Barge Haulers on the Volga 1870 State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg Fine Arts

|

as an example of Russian realism:

|

|

Konstantin Savitsky | Repairing the Railway 1874

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

|

as an example of Russian realism:

|

|

Wassili Perow | Troika 1866 Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow Fine arts

|

as an example of Russian realism:

|

|

Nikolai Yaroshenko | The Stoker, 1878 Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow Fine Arts

|

as an example of Russian realism:

|

|

Gustave Courbet | The Stone Breakers 1849-50

formerly Dresden, Picture gallery; burnt Fine arts

|

As an example of French realism:

|

|

Gustave Doré | London: a pilgrimage

Illustrations in William Blanchard Jerrold's London: a Pilgrimage (1872), 180 wood engravings in all

|

representation of workers and their lives: |

|

Jean-François Millet | The Gleaners, 1857

Musée d'Orsay, Paris Fine arts

|

Description and interpretation of the painting as well as of the motif's background in connection with remarks on realism, in which working people are depicted in works of art and their images are elevated to the salons of society:

|

|

Jean-François Millet | Man with a Hoe, circa 1860 and circa 1862 J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Fine arts

|

Description and interpretation of the painting as well as of the motif's background in connection with remarks on realism, in which working people are depicted in works of art and their images are elevated to the salons of society:

|

|

Jean-François Millet | the Digger 1850

Duluth Tweed Museum of Art, Minnesota Fine arts

|

Interpretation of the painting in connection with remarks on realism, in which working people are depicted in works of art and their likenesses are elevated to the salons of society. |

|

Jean-François Millet | The Sower, 1850 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

|

Interpretation of the painting in the context of remarks on realism, in which working people are depicted in works of art and their likenesses are elevated to the salons of society.[15] |

|

Jean-François Millet | The Angelus, 1857/1859

Louvre, Paris

|

Interpretation of the painting in the context of remarks on realism, in which working people are depicted in works of art and their likenesses are elevated to the salons of society.[15] |

|

Léon Augustin Lhermitte | Paying the Harvesters, 1892

Musée d'Orsay, Paris Fine arts

|

Listed as an example of the representation of the self-confidence of the working class in France after the Revolution:

|

|

Constantin Meunier | Monument to Labour, Brussels - The Dockers, 1880

Quartier de Laeken, Brussels Fine arts

|

Listed as an example of the representation of the self-confidence of the working class in France after the revolution:

|

|

Vladimir Tatlin | Monument to the Third International (Tatlin Tower), 1917 Tatlin Tower and Worker and Kolkhoz Woman by Vera Mukhina 2000

Building

|

In the protagonists' discussion of the significance of the Russian avant-garde for the revolution, this design is an example of the limits it encountered that is not explicitly mentioned:

|

|

Albrecht Dürer | The Prodigal Son 1496

Copper engraving Fine arts

|

Comparison with Dürer's engraving of the Melencolia, which the latter created in 1514, it:

In this context, The Prodigal Son is assigned to Christian iconography, while the Melencolia is assigned to Neoplatonic ideas. The image of the Melencolia is taken up again in the third volume of the novel.[19] ff. |

|

Greek mythology | Mnemosyne, 2nd Century AD National Archaeological Museum of Tarragona

|

It is contrasted with the fascist iconoclasts and book burnings:

Towards the end of the novel, the protective character of memory and its importance for art is taken up again:

|

|

Dante Alighieri | Divine Comedy, 1307-1321 Verse narrative Literature

|

The Divine Comedy occupies a central position, as it is not only discussed in detail, but Peter Weiss' novel itself is reminiscent in parts of a wandering through worlds. The protagonists reflect on the insights and worlds that open up to them with Dante and thus on the importance of education for the working class:

|

|

James Joyce | Ulysses 1914-1921

novel Literature

|

Ulysses is classified by the protagonists as just as disturbing, rebellious, formally and thematically alien as Dante's Divina Commedia and thus placed in relation to it. |

|

Piero della Francesca | Finding and testing the true cross from the cycle

The History of the True Cross, c. 1466

|

The protagonists reflect on the segregation of classes that is inherent in the paintings and question what lessons they themselves, as seekers, can learn from the exclusive, sophisticated art of the rulers and the privileged. In this one, it is the "geometrically fancy walls" of the city view of Arezzo, "the green-blue of the sky taken up by the strangely unspoiled ground, all this was of a vision that eschewed all emotion."[19] |

|

Piero della Francesca | The Victory of Constantine over Maxentius from the cycle

The Legend of the True Cross, c. 1466 Visual arts

|

The protagonists reflect on the class segregation that is inherent in the paintings and question what teaching material the exclusive, sophisticated art of the ruling and privileged can offer for themselves as seekers. In this context, it is especially the two battle paintings of the cycle and the constructed depiction of the soldiers that receive their attention. |

|

Piero della Francesca | The Battle between Heraclius and Chosroes from the cycle

The Legend of the True Cross, c. 1466

|

The protagonists reflect on the class segregation that is inherent in the paintings and question what teaching material the exclusive, sophisticated art of the ruling and privileged can offer for themselves as seekers. In this context, it is especially the two battle paintings of the cycle and the constructed depiction of the soldiers that receive their attention |

|

Hieronymus Bosch | The Haywain Triptych, c. 1490

Museo del Prado

|

Example of a list in which Peter Weiss explains how the faces of the servants and maids stood out in the works that were nevertheless dedicated to the favoured:

Bosch's haywain is not explicitly mentioned, the background arises from the epitaph on Hodann's life, the monument that Peter Weiss wanted to set to the doctor and sex educator Max Hodann in the novel, but which was not included in the published version. |

|

Nicolas Poussin | Et in arcadia ego, 1637-1638 Louvre, Paris

|

Example of an enumeration in which Peter Weiss explains how the faces of the servants and maids stood out in works that were nevertheless dedicated to the favoured:

In a later place, Peter Weiss develops the influence of Géricaults from the interpretation that the Golden Age already contains the moment of terror, the discovery of the tomb and the resigned experience of natural law. Later, Peter Weiss, from the interpretation that the Golden Age already contains the moment of terror of the discovery of the tomb and the resigned experience of the law of nature, develops the influence on Théodore Géricault's painting Raft of the Medusa.[24] |

|

Georges de La Tour | Saint Joseph the carpenter, c. 1640 Louvre, Paris

|

Example of a list in which Peter Weiss explains how the faces of the servants and maids stood out in the works that were nevertheless dedicated to the favoured:

|

|

Jean Siméon Chardin | The Laundress, 1733 St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum Fine arts

|

Example of a list in which Peter Weiss explains how the faces of the servants and maids stood out in the works that were, after all, dedicated to the favoured:

|

|

Jan Vermeer | The Milkmaid (Vermeer), c. 1660

Visual arts

|

Example of a list in which Peter Weiss explains how the faces of the servants and maids stood out in the works that were, after all, dedicated to the favoured:

|

|

Giotto di Bondone | Annunciation to Saint Anne 1304-1306 Cycle of the Life of Joachim Fine arts

|

An allegory in the first-person narrator's dream, in which he matches the images of his barren flat with Bondone's cycle and a surreal scene emerges. In the memories of his parents, the father appears as Joachim and the mother as Anna:

|

|

Giotto di Bondone | Death of the Knight of Celano, 1295

Assisi, Upper Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi Visual arts

|

Symbolism in the dream of the first-person narrator, in which various frescoes flow into the images of the first-person narrator, here the sparse empty flat transitions to a projection of the laid table. |

|

Giotto di Bondone | Legend of St Francis, Vision of the Flaming Chariot, 1297-1300

Assisi, Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi Fine arts

|

Symbol in the first-person narrator's dream with a surreal resurrection image of the father from the kitchen floor and a vision of flight:

|

|

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe | Wilhelm Meister's Journeyman Years, 1821-29

novel Literature

|

Example of the range of the social novel in which the educated bourgeoisie is represented:

|

|

Thomas Mann | Buddenbrooks, 1901

Literature

|

::"Because from Wilhelm Meister onwards to the Buddenbrooks, the world that set the tone in literature was seen through the eyes of those who owned it, the household could be encompassed with such attention to detail and the personality in the richness of all stages of development". |

|

Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret | Colonne Vendôme, 1806-1810

Victory Column Place Vendôme, Paris Fine Arts

|

"In the rubble, in a cloud of dust, lay the emperor, toga and laurel wreath. His betrayal of the revolution had been atoned for." |

| John Heartfield | The meaning of the Hitler salute, Motto: Millions stand behind me, 1932

Rotogravure Visual arts

|

Example of the cultural contributions in the Arbeiter Illustrierte (AIZ) magazine. | |

| Background | Urgent Call for Unity,1932

Appeal

With the Urgent Appeal in June 1932, well-known personalities called for tactical cooperation between the SPD and the KPD against the strengthening NSDAP.

|

Enumeration of artists who supported the urgent appeal and inclusion of later appeals initiated by Willi Münzenberg, editor of the AIZ. | |

| Background | Lutetia Circle,1935-1937

Association

The Lutetia Circle was a committee of artists and politicians of various currents, mainly from the SPD and KPD groups, who met for several conferences at the Hôtel Lutetia in Paris between 1935 and 1937 in order to find an anti-fascist consensus against the Nazi regime.

|

Weiss describes a list of artists who participated in the Lutetia Circle and allusion to Heinrich Heine's essay Lutetia. | |

|

Klaus Neukrantz | Barrikaden am Wedding,1931

Novel of a street from the Berlin May Days

|

In Peter Weiss' book, Neukrantz's book "Barrikaden am Wedding" is extensively acknowledged.[26][27] The first-person narrator juxtaposes it with Franz Kafka's novel, The Castle and reflects extensively on the potential value of both works for the workers' movement. The latter is a purposeful depiction of a historical event, whereas Kafka thinks the subject through in a labyrinthine way. The books "clearly showed how the diversities were dependent on each other, how they complemented each other and could not get along without each other.[28] |

|

Heinrich Heine | Lutetia, 1854

Essay on Politics, Art and Popular Life

|

Excerpt from Heine's work as an ironic allusion to the participants of the Lutetia Circle:

"Now once assembled under the best of intentions, they would have heard, had they been clairaudient, what Heine had to say to them, (...) referring to the epoch in which the sinister iconoclasts, the Communists, would come to rule, break all the marble statues of beauty, smash all the tinsel of art, cut down the poet's laurel groves and plant potatoes there, and turn his poetry books into bags to keep coffee in them and shove tobacco. "[29][30] |

| George Grosz | Café, 1919

|

Example of art that could express the feelings of the first-person narrator, the hatred of greed and selfishness, the murderous loathing of exploitation, subjugation and torture:

| |

| Otto Dix | Triumph of Death, 1934

Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

|

Example of art that could express the feelings of the first-person narrator. | |

| John Heartfield | War and corpses - The last hope of the rich, 1932

Photomontage Visual arts

|

Example of art that could express the feelings of the first-person narrator. | |

|

Pieter Bruegel the Elder | The Fight Between Carnival and Lent, 1559

Fine arts

|

Description of the painting in many details, content as a poor dream of gluttony with the conclusion:

Peter Weiss draws an arc from a total of seven paintings by Pieter Brueghel to Franz Kafka's novel The Castle and introduces this comparison with the statement:

|

|

Pieter Bruegel the Elder | The Gloomy Day, 1565

Fine Art

|

Listed as an example of Brueghel's depictions of farm workers, artisans, peasants and others, all of whom are joyless and drawn with "almost stupid dullness" in all their activities

|

|

Pieter Bruegel the Elder | The Tower of Babel 1563

Fine Art

|

Listed as an example of Brueghel's depictions of farm workers, craftsmen, peasants,

|

|

Pieter Bruegel the Elder | The Procession to Calvary, 1564

Fine arts

|

Listed as an example of Brueghel's depictions of farm workers, craftsmen, peasants, "(...) whether they, led Jesus to crucifixion," |

|

Pieter Bruegel the Elder | The Peasant Dance, 1568

Kunsthistorisches Museum

|

Listed as an example of Brueghel's depictions of farm workers, craftsmen, peasants, "(...) or whether they were spinning in the round dance at the fair." |

|

Pieter Bruegel the Elder | Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,1558

Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium Fine arts

|

Description of the painting with reference to the indifferent attitude of the persons in the picture and the depiction of the aphorism:

|

|

Pieter Bruegel the Elder | Massacre of the Innocents, 1565-1567

Fine arts

|

Description of the painting with reference to the nameless despair and the inescapability of the horrific:

This train of thought is continued in the following description of Franz Kafka's novel The Castle:

|

|

Franz Kafka | The Castle, 1922

unfinished novel Literature

The novel depicts the futile struggle of the surveyor K. for recognition, through a mysterious system represented by an all-dominating castle and its representatives.

|

Description and explanations of what the first-person narrator learns from the novel. In particular, he sees parallels to the reality of the oppressed and exploited in the non-questioning of domination and the resulting hopelessness, and that it is precisely this that creates the situation in which the position that everyone occupies in society is not questioned, but only fought for its recognition, even if it is to do unrelated work:

"It was only suddenly felt that something important, momentous was going on, an immense, worldwide operation that we, as tiny components of the machinery, had to serve. This is how the voice of imperialism sounded to those who had hitherto been too weak to acquire knowledge about the interrelationships of economic processes. But even when we had gained an insight, we too remained equally far removed from this whirring, although we were involved in it as stokers, mechanics, load carriers, cart pushers."[31] |

|

Romain Rolland | Jean Christophe,1904–1912

Novel

|

For example, in the development of workers' education:

|

|

André Gide | Counterfeiters, 1925

Novel

|

Used as an example in the development of workers' education. |

|

Knut Hamsun | Hunger, 1890

Novel

|

Used as an example in the development of workers' education. |

|

Elias Canetti | Die Blendung,1931-1932

novel

|

Used in the development of workers' education:

|

|

Louis-Ferdinand Céline | Journey to the End of the Night,1932

Novel

|

Used in the development of workers' education:

|

|

Antoni Gaudí | Sagrada Família, begun in 1882

unfinished basilica,

Barcelona

|

Description of the building and discussion of the political contradictions that the first-person narrator reflects on during the visit. The cathedral stands as a symbol of the "banality of an empty mendacious religion"[32] and is comparable to the tendencies of the revolutionary movement, which is held down by its leadership in petty-bourgeois idealism.[33] |

|

Antoni Gaudí | Portal of Hope, 1891-1900

East façade of the Sagrada Família Barcelona Fine arts

|

The motif of the Bethlehemite infanticide, discussed several times in the novel, is also found at the Sagrada Família in a sculptural group:

|

|

Antoni Gaudí | Casa Batlló, 1877

Building

Barcelona, Passeig de Gràcia

|

The building is also visited by the protagonists during their stay in Barcelona. |

|

Antoni Gaudí | Casa Milà, 1906-1910

Building

Barcelona, Passeig de Gràcia

|

The building is also visited by the protagonists during their stay in Barcelona. |

|

Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle | La Marseillaise, 1792

Song

|

A discussion about the necessity of slogans and the banality of contexts, compared to Gaudí's Sagrada Família:

|

|

Eugène Pottier (Text),

Pierre Degeyter (Melody) |

The Internationale, 1871-1888

Song

|

A discussion about the necessity of slogans and the banality of contexts, compared to Gaudí's Sagrada Família:

|

|

Miguel de Cervantes | Don Quixote, 1605-1615 Novel

|

The figure of Don Quixote is performed repeatedly, especially during the first-person narrator's stay in Spain: as an epic of Spain

as the motif of a mural in Albacete, in trains of thought on heroic productions. |

|

Background | International Brigades

|

List of artists who joined or supported the International Brigades. |

|

Richard Wagner | Tannhäuser, 1842-1845 Opera

|

Emblematic of a gathering of internationalists in a former palace in Albacete that served as an infirmary. The role music by Wagner and others who were there was played on a pianola:

|

|

Pietro Mascagni | Cavalleria rusticana, 1890 Opera

|

Emblematic of a gathering of internationalists in a former palace in Albacete that served as an infirmary. The role music by Mascagni and others who were there was played on a pianola. |

| Jean Sibelius | Valse triste, 1904 Waltz

|

Emblematic of a gathering of internationalists in a former palace in Albacete that served as an infirmary. The role music by Mascagni and others who were there was played on a pianola. | |

|

Giuseppe Verdi | March from Aida, 1871 Opera

|

Emblematic of a gathering of internationalists in a former palace in Albacete that served as an infirmary. The role music by Mascagni and others who there was played on a pianola. |

|

Francisco de Goya | Los caprichos, 1796-1797 80 aquatint etchings

|

The first-person narrator describes his ideas about the country and the republic of Spain as influenced, among other things, by Goya's satirical works, the Caprichos. |

|

Francisco de Goya | The Disasters of War,1810-1814 82 etchings

|

The first-person narrator's ideas about the country and the republic of Spain are influenced, among other things, by Goya's graphic series of disasters. They are used in the novel as a metaphor in the sense of the title of the first sheet in the series "Sad Forebodings of What is Going to Happen".[35] |

|

Middle Ages | Castillo de Denia, 11th and 12th century

Dénia

|

Description and examination of the Spanish history of colonialism from antiquity through the Reconquista to the Spanish Civil War.[36] |

| Pablo Picasso | Guernica, 1937 Madrid, Museo Reina Sofía

|

Discussion and interpretation of the painting, both on the basis of the process of creation documented photographically by Dora Maar, the art-historical debate of the contemporary novel, and in detailed comparison with myths, motifs and in the context of other works of art.

| |

|

Greek mythology | Nike Mythology

|

The goddess Nike is recognised in the novel both in Picasso's Guernica,

as in the figure of the femme du peuple in Delacroix's Liberty Leads the People:

|

|

Greek mythology | Minotaur

Mythology

|

In the discussion about Picasso's Guernica, the depiction of the bull is equated with the mythological hybrid of the Minotaur:

Furthermore, its importance in Picasso's world of motifs is questioned and his etching Minotauromachy is used for further comparison. |

|

Greek mythology | Pegasus

Mythology

|

In the first versions of Picasso's Guernica, Pegasus initially occupied a central representation; in the final version he is finally missing. The protagonists discuss the significance of this absence and develop it further on mythology:

"Turning away from the Gorgo, only catching her grimacing face in a mirror, Perseus had killed her, and this evasion was also Picasso's. The attacking violence remained invisible in his painting. (...) Perseus, Dante, Picasso remained whole and handed down what their mirror had caught, the head of Medusa, the circles of the Inferno, the blasting of Guernica."[42] |

|

Greek mythology | Medusa

|

The myth of Medusa, taken up in the discussion of the Pegasos painting, has further references throughout the novel, for example in the title of the painting by Géricault and in the 2nd volume in the description of the city of Paris. |

| Pablo Picasso | The Dream and Lie of Franco, 1937

etchings, picture plates with 18 pictures on 2 plates

|

Description and inclusion of the etchings in the interpretation of the painting Guernica:

| |

| Pablo Picasso | Mother with dead child, 1937

|

The motif of a mother with a dead child, particularly in the horrific images of the Massacre of the Innocents in Bethlehem, is taken up repeatedly in the novel. In the discussion of the painting Guernica, it forms an iconographic transition to the painting of the Minotauromachy. Elsewhere in the novel, the motif can be found in Pieter Brueghel, as a fresco by Giotto di Bondone in the Arena Chapel, and in sculptural groups on Antoni Gaudí's Sagrada Família.[45][44] | |

|

Guido Reni | Massacre of the Innocents, 1611–1612 Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna

|

The motif of a mother with a dead child, particularly in the horrific images of the Massacre of the Innocents in Bethlehem, is taken up repeatedly in the novel. In the discussion of the painting Guernica, it forms an iconographic transition to the painting of the Minotauromachy. The painting by Reni serves as an example here, as do the works of art by Breughel and the sculptural group by Gaudí mentioned earlier.[43][44] |

|

Nicolas Poussin | Massacre of the Innocents, 1625–1629 Musée Condé, Chantilly

|

The motif of a mother with a dead child, particularly in the horrific images of the Massacre of the Innocents in Bethlehem, is taken up repeatedly in the novel. In the discussion of the painting Guernica, it forms an iconographic transition to the painting of the Minotauromachy. The painting by Reni serves as an example here, as do the works of art by Breughel and the sculptural group by Gaudí mentioned earlier.[43][44] |

| Fernand Léger | Nudes in the forest, 1909–1911

Otterlo, Rijksmuseum Kroller-Muller

|

Inclusion in the interpretation of the painting Guernica, especially the formal language forces the viewer to build and combine. The gaze is awakened.[45][44] | |

| Lyonel Feininger | The Cathedral of Socialism, 1919

Etching

|

Not explicitly mentioned in the description of Picasso's Guernica, yet listed as an example of how our gaze is awakened: | |

|

Franz Marc | Tower of the Blue Horses, 1913

formerly Berlin, Kronprinzenpalast; lost since 1945

|

Listed comparatively in the description of Picasso's Guernica as an example of how our gaze is awakened, "The meteoric spraying of forms at the Tower of the Blue Horses allowed a vitality to appear that conventional means of depiction could never achieve.[48][49] |

|

Franz Marc | Fate of the Animals, 1913

Basel, Art Museum

|

The "meteoric spraying forms" attributed to the Tower of Blue Horses in the novel, as well as the reference to Picasso's painting, apply increasingly to the fates of animals.[32][46][49] |

| Pablo Picasso | Minotauromachy, 1935, Etching

|

Inclusion of the etching in the interpretation of the painting Guernica, the motif world of the minotauromachy stands here for the personal-sexual reference in contrast to the representation in the painting with the public-political background. However, it is recognised as "the well from which the Guernica image had risen".[46][44] | |

|

Henri Rousseau | The War - Ride of Discord, 1894

Paris, Musée d'Orsay

|

Inclusion in the interpretation of the painting Guernica: |

|

Andrea Mantegna | The lamentation of Christ, circa 1470 to circa 1474

|

Naming the root of Picasso's Guernica in the motif of the Lamentation of Christ:

|

|

Enguerrand Quarton (Meister des Pietà von Avignon) |

Pietà of Villeneuve-lès-Avignon, c. 1455

Louvre, Paris

|

Naming the root of Picasso's Guernica in the motif of the Lamentation of Christ:

|

|

Beatus of Liébana | Saint-Sever Beatus, Mid-11th century

book illumination

|

Description of the apocalypse depicted here as one of the roots of Picasso's Guernica: |

|

Eugène Delacroix | Liberty Leading the People, 1830

Louvre, Paris

|

Description and interpretation of the painting, iconographic classification and comparison with Picasso's Guernica and Géricault's Raft of the Medusa. The protagonists see the terrible thing in the painting in knowing what followed July 1830:

|

|

Honoré Daumier | Rue Transnonain, 15 April 1834

|

Discussed as a counterpart to Delacroix's Liberty Leads the People and as influenced by Géricault's Raft of the Medusa.[53] |

|

Théodore Géricault | The Raft of the Medusa, 1818-19

Louvre, Paris

|

Intensive examination, description and interpretation as well as illumination of the background of the painting. It is set in relation to Picasso's Guernica as a depiction of terror and compared to Delacroix's The Liberty Leads the People in historical representation. "Géricault's painting, however, had been a dangerous attack on established society."[54]

The biography of the artist and the political background of the Méduse affair are also discussed, as are the personal accounts of survivors. In the second volume of the novel, Peter Weiss revisits the artist and his work and describes the creative process with a multitude of studies and drafts. From the initially political reading of the painting, various narrative levels, some of which overlap, are directed to a personal level of experience; the political catastrophe turns into a personal-existential crisis. |

|

Francisco de Goya | The Third of May, 1814

Madrid, Museo del Prado

|

Discussion and interpretation of the painting, initially set in relation to Picasso's Guernica and compared with Géricault's Raft of the Medusa, the painting is taken up many times in later chapters. In describing and interpreting the painting, the protagonists engage in an argument about martyr-like death:

|

|

Francisco de Goya | The Second of May 1808, 1814

Madrid, Museo del Prado

|

This painting, which is not explicitly mentioned in the novel, forms the counterpart to the shooting of the insurgents and depicts the events that preceded the executions, the struggle of the people of Madrid against the Napoleonic troops. Both paintings were intended by Goya as an ensemble, the concrete historical statement is seen as a testimonial impulse, which is also inherent in Peter Weiss' novel itself.[35] |

|

Eugène Delacroix | The Barque of Dante, 1822

Louvre, Paris

|

In Delacroix's interpretation of The Liberty, the people list it as a comparison to previously created paintings:

The mention of this painting simultaneously contains a recourse to the discussion of Dante's Divine Comedy. |

|

Eugène Delacroix | Chios massacre, 1824

Louvre, Paris

|

The painting is placed in relation to Picasso's Guernica, moreover, in Delacroix's interpretation The Liberty Leads the People is listed as a comparison to previously created paintings:

|

|

Théodore Géricault | Wounded Cuirassier Leaving the Field of Battle, 1814

Louvre, Paris

|

Example of Géricault's paintings before the Raft of the Medusa: |

|

Théodore Géricault | Horse Stopped by Four Young People, 1817

Rouen, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen

|

Example of Géricault's paintings before the Raft of the Medusa: |

|

Théodore Géricault | The 1821 Derby at Epsom, 1821

Louvre, Paris

|

Example of Théodore Géricault's personal background: |

|

Jan Vermeer | The Lacemaker, c. 1665

Louvre, Paris

|

Resumption of the theme of work in the performing arts with the idea

|

|

Adolph Menzel | The Rolling Mill, 1875

Berlin, Old National Gallery

|

Description and interpretation of the painting in the context first of all of the first-person narrator's thoughts on the culture of the workers and the fascination that this representation exudes. With further contemplation, he develops a critique of the painting's entrenchment of conditions:

Rather, the painting symbolises the expansion of industrial imperialism; Peter Weiss relates it to two other paintings by Menzel to form a triptych of recent German history: in the Nationalgalerie exhibition, it is flanked by the paintings King Wilhelm's Departure for the Army in 1870 and Das Ballsouper. |

|

Adolph Menzel | Departure of King Wilhelm I. to the Army on 31 July 1870, 1871

Berlin, Old National Gallery

|

Left part of the triptych on German history that the first-person narrator recognises in the arrangement of Menzel's three paintings in the National Gallery, it represents the prelude to the Franco-Prussian War of 1870:

|

|

Adolph Menzel | The Dinner at the Ball, 1878

Berlin, Old National Gallery

|

Right part of the triptych on German history that the first-person narrator recognises in the arrangement of Menzel's three paintings in the National Gallery:

|

|

Robert Koehler | The Strike in the region of Charleroi, 1886

Berlin, Deutsches Historisches Museum

|

Description and discussion of the painting as a counterpart to Menzel's Iron Rolling Mill, which depicts the workers as acting subjects. |

|

Edvard Munch | Workers on their Way Home, c. 1914

Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst

|

Described and presented as an allegory of a way of life,

|

|

Théodore Géricault | The murderers carry the body of Fualdès to Aveyron, c. 1818

From the series The Murder of Antoine-Bernardin Fualdès,

Paris, Musée des Beaux-Arts

|

In the second volume of the novel, Peter Weiss takes up the discussion of Géricault's painting "The Raft of the Medusa" and deals intensively with the creative process. The process is introduced with a series of drawings on the murder of Antoine-Bernardin Fualdès, with which Géricault fitted a daily political event of the sensational press of the time into artistic form.[8][63] |

|

Jean-Baptiste Henri Savigny and Alexander Corréard | The Shipwreck of the Frigate Medusa, 1821

Report

Paris

|

The report by Savigny and Corréard is included in the creative process for Géricault's painting Raft of the Medusa. Due to the partly verbatim reproduction, the narrative levels overlap. The first-person narrator's description of the shipwreck represents Géricault's confrontation with the background.

Both the book and the painting draw the narrator into the events. |

|

Théodore Géricault

Cannibalism on the Raft of the Medusa, 1818-1819

Louvre, Paris

|

Géricaults Arbeitsprozess wird anhand der fünf Kompositionsstudien besprochen, die die Themen Meuterei, Kannibalismus, Sichtung der Brigg, Begrüßung eines Rettungsboots und die Rettung bearbeiten.[66] | |

|

Johann Heinrich Füssli | Ugolino and his Sons Starving to Death in the Tower,1809

Steel engraving by Moses Haughton after the painting by J.H. Füssli (1806)

Kunsthaus Zürich

|

The first-person narrator sees the portrayal of Count Ugolino as a model for the sketch of cannibalism on Géricault's Raft of the Medusa. The novel thus makes a further reference to Dante's Divine Comedy.[66] |

|

Greek Mythology | Hippolytus

Son of the hero Theseus and the Amazon queen Hippolyta

|

In an allegorical correspondence with the myth, Géricault's relationship with his stepmother is described and woven into the process of working on the Raft of the Medusa, which is accompanied by hallucinations. |

|

Jacques-Louis David | Oath of the Horatii, 1784

Louvre, Paris

|

In the sequence of David's pictures it becomes clear "how, after the classicist spirit of the revolution, after the idealistic flight of fancy, the approach to the megalomania of imperialism could be found immediately.[67][68] |

|

Jacques-Louis David | The Intervention of the Sabine Women,1799

Louvre, Paris

|

In the sequence of David's pictures it becomes clear "how after the classicist spirit of the revolution, after the idealistic flight of fancy, the approach to the megalomania of imperialism could immediately be found." |

|

Jacques-Louis David | The Coronation of Napoleon, 1805-1807

Louvre, Paris

|

In the sequence of David's pictures it becomes clear "how after the classicist spirit of the revolution, after the idealistic flight of fancy, the approach to the megalomania of imperialism could immediately be found." |

|

Théodore Géricault | Studies of Severed Limbs,1818

oil study

Paris, Louvre

|

Example of one of Géricault's numerous studies of anatomical models whose genesis was incorporated into the novel. |

|

Théodore Géricault | Studies after decapitated persons,1818

Stockholm, National Museum

|

The painting is first used as an example for further studies by Géricault. A description of the depiction of the Guillotined follows a few chapters later, in connection with the "Studies of the Definitive" and the work of Charles Meryon. |

|

Théodore Géricault | A Madwoman and Compulsive Gambler, 1822

Louvre, Paris

|

Example of Géricault's works created after the creation of the Raft of the Medusa:

|

|

Théodore Géricault | Insane Kleptomaniac, 1822

Louvre, Paris

|

Example of Géricault's works created after the creation of the Raft of the Medusa:

|

|

Théodore Géricault | Liberation of the Inquisition Victims, 1823

Louvre, Paris

|

Mention in the account of Géricault's dying:

|

|

Théodore Géricault | The Flood, 1815-1816

Louvre, Paris

|

Description and interpretation as symptomatic of Géricault's life: there is no saving ark in the picture.

|

|

Nicolas Poussin | Winter, 1660-1664

Louvre, Paris

|

Description and comparison with Géricault's painting Flood. Poussin's painting served as a model for the latter. |

|

Théodore Géricault | Head of a White Horse (Tete de cheval blanc), c. 1815

Louvre, Paris

|

Mentioned and described as having been painted in the same period as The Flood, with reference to the tenderness unfolded in this painting. |

|

Théodore Géricault | The lime kiln, 1822-1823

Louvre, Paris

|

Description and interpretation of the painting in the context of the last year of Géricault's life and the observation that it does not show a decisive course of development:

|

|

Michelangelo | The Last Judgement, 1534-1541

Sistine Chapel, Rome

|

In Michelangelo's work, the influence on Géricault's Raft of the Medusa is recognised and at the same time the integration into art history:

The direct influence of the painting The Last Judgement, which art historians have recognised, is not named in the novel.[70] |

|

Honoré Daumier | Allegory of the Republic, 1848

Bildende Kunst

|

Discussion as a continuation of Géricault's Raft of the Medusa and classification in the sequence of art history:

|

|

Vincent van Gogh | Agostina Segatori Sitting in the Café du Tambourin, 1887

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

|

In the depiction of an imaginary scene in which the protagonists meet the artist in Montmartre, the café Le Tambourin is mentioned:

|

|

Vincent van Gogh | Flowering plum tree, after Hiroshige, 887

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

|

Example of a painting by Van Gogh painted from a woodcut by the Japanese artist Utagawa Hiroshige; in the novel, while depicting an imaginary scene, the Japanese woodcuts hanging in the Café Tambourin next to numerous paintings by Van Gogh are mentioned. |

|

Camille Corot | The Italian Agostina, 1866

National Gallery of Art, Washington

|

In the depiction of an imaginary scene of meeting Van Gogh in Montmartre, the latter meets "Corot, Monet, Seurat, whom he did not recognise". A relationship is established through Agostina Segatori, the owner of Café Le Tambourin, who was painted by Corot in 1866 and who was Van Gogh's patron some twenty years later.[72][73] |

|

Location | Bateau-Lavoir,

Paris, Montmartre, Rue Ravignan

Le Bateau-Lavoir was a house on Montmartre in Paris on Rue Ravignan that entered art history because at the turn of the 20th century a group of artists who later became famous rented studios and lived there. In 1908, a much-discussed banquet for Henri Rousseau took place here.

|

Description of the house and its surroundings:

|

|

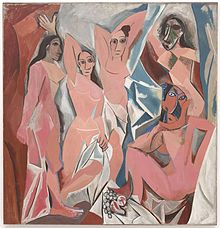

Pablo Picasso | Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907

Museum of Modern Art, New York

|

The painting is mentioned as a work created in the Bateau-Lavoir and thus illustrates the importance of the place as a place of creativity in the dawn of modernity. |

|

Ernest Meissonier | The barricades in the Rue de la Mortellerie, 1848-1849

Louvre, Paris,

|

The first-person narrator sees the painting as a counterpart to Delacroix's painting of the barricades:

|

|

Fra Angelico | Coronation of the Virgin, c. 1430

Louvre, Paris

|

Enumeration of paintings perceived by the first-person narrator during the last visit to the Louvre, more detailed explanations are noted in Peter Weiss's notebooks, in which he discusses in particular the scenes from the life of Dominic.[76][77] |

|

Simone Martini | Orsini Altar, Scene: Carrying of the Cross, 1336-1342

Louvre, Paris

|

Enumeration of paintings perceived by the first-person narrator during the last visit to the Louvre.[76][78][79] |

|

Bernat Martorell | The Flagellation of St George, 1435

Louvre, Paris

|

Enumeration of paintings perceived by the first-person narrator during the last visit to the Louvre and description of the images of torture.[76][78][80] |

|

Stefano di Giovanni | The blessed Ranieri frees the poors from a Florentine jail, 1439-1444

Louvre, Paris,

|

Description and personal interpretation of the first-person narrator during the last visit to the Louvre, in contrast to the other pictures, the pictures of torture, this is seen by him as a metaphor of a utopian moment, promising salvation: |

|

Location | Cabaret Voltaire

Place, Zürich, Spiegelgasse

|

Cabaret Voltaire "became the symbol of the violent, double, the true and the dreamed revolution".[82] |

| P.G. Lotorew | Portrait of Karl Marx, 1917

Moscow, Lenin Museum

|

In a detailed description of Lenin's study, this Marx portrait is mentioned. | |

|

Hugo Rheinhold | Monkey with skull, 1892

|

This bronze is mentioned in a detailed description of Lenin's study. |

|

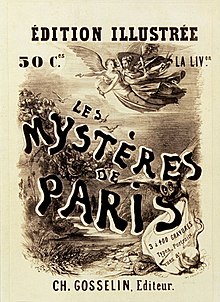

Eugène Sue | The Mysteries of Paris, 1843

|

In the description and depiction of the novel and its background, a comparison with the novel's present is prefaced:

In the context of the prints and poems of Charles Meryon, thoughts of Arthur Rimbaud and Friedrich Hölderlin, the first-person narrator considers the city, and in particular the changes brought about by Haussmann's urban renewal of Paris in the mid-nineteenth century, and sets them in relation to political and social conditions. |

|

Charles Meryon | Tourelle, Rue de l'Ecole de Médicine, 1861

Etching

|

n a compilation of Eugène Sue's The Mysteries of Paris with the prints and poems of Charles Meryon, Thoughts on Arthur Rimbaud and Friedrich Hölderlin, the first-person narrator looks at the city and in particular the changes brought about by the Haussmannian urban renewal of Paris in the mid-nineteenth century and sets them in relation to political and social conditions. A metaphor in this is the depiction of Tourelle with its image of the house where Jean Paul Marat was assassinated in 1793.[84] |

|

Jan Vermeer | The Art of Painting,1664/68

Kunsthistorisches Museum

|

Symbolic with the coincidence of the map of Belarus, the name for the united Belarus, in Lenin's study and the map depicted in Vermeer's painting.[85][86] |

|

Otto Stockhausen | St. Pauli Elbtunnel, 1911

Postcard

|

Description in a dream image of the first-person narrator, in which he is initially transported to his childhood. Through surreal dream transmissions, he sees a scene of persecution in which he loses his mother and is himself at the mercy of his own helplessness in the social and political system. |

|

Charles Meryon | The Mortuary, Quai du Marché-Neuf, Paris, 1854

Etching

|

This cityscape of Paris is drawn upon in an argument by the first-person narrator about violent death, into this image he incorporates the description of Géricault's studies of decapitated people, he calls his thoughts the study of the definitive.[87][61] |

|

William Blake | Living mask, 1823

by J.S. Delville

|

The mask is mentioned in the account by Rosalinde von Ossietzky, Carl von Ossietzky's daughter, of her father's persecution and death:

There is further mention of Blake in the section on Bert Brecht's library:

|

|

Albrecht Altdorfer | The Battle of Alexander at Issus, 1528–1529

Old Pinakothek, Munich

|

Comparison of the painting with the political situation in Europe at the beginning of the war in 1939; generally referred to as a battle painting in the novel, it can nevertheless be identified through the description as well as notes from Peter Weiss' notebooks.[88][89][77] |

| Hans Tombrock | Discussion about the defeat in the Spanish Civil War at Brecht's home in Lidingö, 1939

Charcoal drawing

|

The drawing served Peter Weiss as a model for the description of Bertolt Brecht's house in exile in Lidingö. At the same time, there is an argument about the artist and his relationship to women, which can also be applied to Brecht.[90] | |

|

Bertolt Brecht | Flyer for "The Guns of Mrs Carrar", 1937

Play

|

The play is included in the novel's plot, Brecht expresses here that the play had to be rewritten because of the situation. |

|

Pieter Bruegel the Elder | Dull Gret, 1563

Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp,

|

Description of the painting in many details, interpretation as a symbol of the conditions in Europe after the Spanish Civil War. |

|

Pieter Bruegel the Elder | The Triumph of Death, 1562-1563

Museo del Prado, Madrid

|

Description of the painting in many details, interpretation as a symbol of the conditions in Europe after the Spanish Civil War. |

|

Käthe Kollwitz | Mother with Children,1927-1937

Käthe Kollwitz Museum, Berlin

|

The brief mention of the artist in connection with Margarete Steffin,

establishes a pictorial reference to the workers' wives she depicted as a counter-image to Brueghel's Dull Gret, as is evident in this sculpture of the preserving mother.[91] |

From "Romance Sonámbulo",

("Sleepwalking Romance"), García Lorca |

Federico García Lorca | Romance sonámbulo,1928

Poem

|

"This green. This green that Lorca sang about..." |

|

Francesco Sabatini | Pardo Palace, 1772

Building

Madrid

|

Description as a symbol of feudalism, occupied by the International Brigades during the Civil War.[92] |

|

Francisco de Goya | Charles IV of Spain and His Family,1800-1801

Museo del Prado, Madrid

|

Description of the painting with the question of the meaning of the client: "You know the picture (...) in which Goya captured the royal family, fourteen figures, bloated, witch-like, doll-like, stupid and fat, in glamorous robes, magnificent uniforms." |

|

Bertolt Brecht | Mother Courage and Her Children,1938-1939

Drama

|

Description of the work on the play by Brecht's working group. |

| Bertolt Brecht | Das Verhör des Lukullus (The Interrogation of Lucullus), 1940

Radio play

|

Description of the work on the play by Brecht's working group. | |

|

Bertolt Brecht

Leben des Galilei (The Life of Galileo), 1939

Drama

|

Describing the problems of getting the play performed | |

|

Background | Kornhamnstorg

|

The Uprising was a material Brecht worked on for a time while he was in exile in Sweden, but eventually discarded. The first-person narrator takes up the story in his own literary development. |

| Bertold Brecht | Flüchtlingsgespräche (Refugee Talks), 1941-1949

Prose pieces

|

Enumeration of Brecht's works | |

|

Jacob Elbfas

|

Vädersolstavlan, (Weather Sun Painting),around 1630

After a painting by Urban the Painter (1535)

Storkyrkan, Stockholm

|

Description of the picture in connection with the account of the work of Brecht's working group on the Engelbrekt drama.[93] |

|

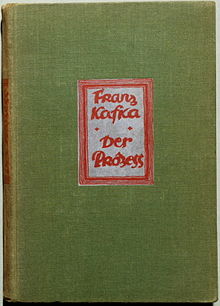

Franz Kafka | The Trial, 1914-1924 (1925)

Unfinished novel

|

Listed in the extensive listing of Brecht's library in a chapter where the first-person narrator helps with packing:

|

|

Franz Kafka | Amerika, 1911-1914 (1927)

Unfinished novel

|

Listed in the extensive listing of Brecht's library in a chapter where the first-person narrator helps with packing:

|

|

George Grosz | The Face of the Ruling Class, 1921,

cycle of 57 political drawings

|

Listed in the extensive enumeration of Brecht's library in one chapter, in which the first-person narrator helps to pack. |

|

Urban Hjärne | Rosimunda, 1665

Play

|

Description of the poet's travels and his acting, while the first-person narrator digresses into thoughts of his own childhood in concern for his mother's health. |

|

Middle Ages | Lovö kyrka, 12th and 13th century

church, Lovön near Stockholm

|

Depiction and description of some details from this medieval church in a scene in the novel where Lotte meets Bishop Herbert Wehner in this church.[94] |

|

Burchard Precht | Pulpit in Lovö church, around 1700

Lovön near Stockholm

|

Mentioned in a scene in the novel where Lotte meets Bishop Herbert Wehner in Lovö kyrka. |

| Johan Sylvius | The fresco in Lovö church, around 1690

Lovön near Stockholm

|

Mentioned in a scene in the novel where Lotte meets Bishop Herbert Wehner in Lovö kyrka. | |

|

Suryavarman II | Angkor Wat, around 1300

Temples

Angkor, Cambodia

|

The novel describes the relief of the South Gallery, The Royal Parade, which is used as the basis for an argument about the ruler's sense of power and the obedience demanded of him. |

|

Albrecht Dürer | Melencolia I, 1514

Copper engraving

|

Description and interpretation of the print and placed by the first-person narrator in the context of his mother's illness: "Surrounded by things of research, building and ultimate exploration, she had emerged from a childlike existence, in her closed what seemed unfathomable to our thinking."[21]

The painting already found mention in the first part of the novel, when it was juxtaposed with Dürer's print The Prodigal Son.[18] |

|

Middle Ages | Dance of Death, around 1500

Church of Our Lady, Berlin,

|

Description in a scene in which the protagonists seek shelter from a bombing raid in the church, and emblematic of the following depiction of the execution and murder of resistance fighters in National Socialist Germany. |

| Background | Konstnärer i landsflykt, 1944

(Artist in Exile)

Exhibition, Stockholm

|

Description of the founding of a cultural association in Sweden, the organisation of an exhibition and a list of the artists involved. | |

|

Ancient | The missing Heracles

Detail in the Pergamon Altar

|

The novel concludes:

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Badenberg & Die Ästhetik und ihre Kunstwerke. Eine Inventur 1995, p. 115.

- ^ Pike, David L. (5 September 2018). Passage through Hell: Modernist Descents, Medieval Underworlds. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-5017-2947-8.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 9.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, pp. 36, 46, 50.

- ^ a b Weiss Volume 1, p. 53.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 267.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 210.

- ^ a b Weiss Volume 1, p. 10.

- ^ Weiss Volume 3, p. 20.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 58.

- ^ "Originalstiche von Gustave Doré (1832-1883)" (in German). Spiegel-Verlag. Der Spiegel. 6 July 2005. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 61.

- ^ Doré, Gustave; Jerrold, Blanchard (2011). London : a pilgrimage. Easton Press: Norwalk, Connecticut. OCLC 1057895718.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 206.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 63.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 227.

- ^ a b Weiss Volume 1, p. 76.

- ^ Weiss Volume 3, p. 132.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 77.

- ^ a b Weiss Volume 3, p. 134.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 81.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 86.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 218.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 92.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 161.

- ^ "Klaus Neukrantz - Barrikaden am Wedding (1931)". Nemesis - Socialist Archive for Fiction (in German). Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 182.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 164.

- ^ "Reports on politics, art and folklife, Draft of the preface". Zeno (in German). Berlin. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 178.

- ^ a b Weiss, Peter (1981). Notizbücher:1971-1980. Edition Suhrkamp, 1067,2 = N.F. 67,2. Vol. 2 (1st ed.). Frankfurt: Suhrkamp. p. 313. ISBN 9783518110676.

- ^ Weiss Volume 3, p. 208.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 209.

- ^ a b Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 188.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 176.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 348.

- ^ a b Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 213.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 333.

- ^ a b Weiss Volume 1, p. 341.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 334.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 339.

- ^ a b c Weiss Volume 1, p. 335.

- ^ a b c d e f g Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 215.

- ^ a b Weiss Volume 3, p. 335.

- ^ a b c Weiss Volume 1, p. 336.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 180.

- ^ Weiss Volume 3, p. 336.

- ^ a b Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 200.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 337.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 165.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 342.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 173.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 343.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 346.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, pp. 176, 215.

- ^ a b c Weiss Volume 1, p. 347.

- ^ a b Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 184.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 349.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 355.

- ^ a b c Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 203.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 356.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 181.

- ^ Weiss Volume 2, p. 11.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 183.

- ^ a b Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 185.

- ^ Weiss Volume 2, p. 23.

- ^ a b Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 174.

- ^ a b Weiss Volume 2, p. 33.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 205.

- ^ Weiss Volume 2, p. 34.

- ^ Weiss Volume 2, p. 35.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 172.

- ^ Weiss Volume 2, p. 38.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 167.

- ^ a b c d Weiss Volume 2, p. 41.

- ^ a b Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Weiss Volume 2, p. 495.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 225.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 201.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 222.

- ^ Weiss Volume 2, p. 59.

- ^ Weiss Volume 2, p. 65.

- ^ Weiss Volume 2, p. 69.

- ^ Weiss Volume 2, p. 75.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 230.

- ^ Weiss Volume 2, p. 120.

- ^ Weiss Volume 2, p. 142.

- ^ Weiss, Peter (1981). Notizbücher:1971-1980. Edition Suhrkamp, 1067,2 = N.F. 67,2. Vol. 2 (1st ed.). Frankfurt: Suhrkamp. pp. 277, 606. ISBN 9783518110676.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 228.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 196.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 209.

- ^ Badenberg & Kommentiertes Verzeichnis 1995, p. 229.

- ^ Weiss Volume 1, p. 83.

Bibliography

[edit]- Badenberg, Nana (1995). "Die Ästhetik und ihre Kunstwerke. Eine Inventur". In Honold, Alexander; Schreiber, Ulrich; Badenberg, Nana (eds.). Die Bilderwelt des Peter Weiss (in German) (1st ed.). Hamburg: Argument-Verlag. pp. 114–163. ISBN 9783886192274.

- Badenberg, Nana (1995). "Kommentiertes Verzeichnis der in der Ästhetik des Wider-stands erwähnten bildenden Künstler und Kunstwerke". In Honold, Alexander; Schreiber, Ulrich (eds.). Die Bilderwelt des Peter Weiss (in German) (1st ed.). Hamburg: Argument-Verlag. pp. 163–231. ISBN 9783886192274.

- Weiss, Peter (1987). Die Ästhetik des Widerstands Bd. 1 (in German) (2nd ed.). Berlin: Henschelverlag Kunst und Gesellschaft. ISBN 9783362001854.

- Weiss, Peter (1988). Aesthetik des Widerstands. Edition Suhrkamp, 1501 (in German). Vol. II. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp. ISBN 9783518115015. OCLC 1283249147.

- Weiss, Peter (1987). Die Ästhetik des Widerstands Bd. 3 (in German) (2nd ed.). Berlin: Henschelverlag Kunst und Gesellschaft. ISBN 3362001874.