Ancient history of Bangladesh

Ancient history of Bangladesh | |

|---|---|

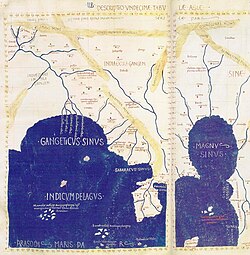

Ptolemy's Geography illustrating the Ganges and beyond |

| History of Bangladesh |

|---|

|

|

|

The ancient history of Bangladesh is a period of time, part of a series on the History of Bangladesh, dating back over multiple millennia. The region's ancient history is comprised of a sequence of different independent regional kingdoms and the various Magadha dynasties. Due to Bangladesh's geography and the plethora of rivers, namely the Ganges, Meghna and Padma rivers, and their constant shifting, archeological evidence regarding the ancient history of Bangladesh has been scarce. Due to this, many historians have been more partial to prioritising other, well documented or recent areas of the history of Bangladesh.

Overview

[edit]It is believed that there were movements of Austro-asiatics, Tibeto-Burmans, Indo-Aryans, Dravidians and Mongoloids, including a people called Vanga, into Bengal.[1] The Oxford History of India categorically claims that there is no definitive information about Bengal before the third century BCE.[citation needed] One view argues that humans entered Bengal from China 60,000 years ago. Another view claims that a distinct regional culture emerged 100,000 years ago.[citation needed]

Due to Bangladesh's natural geography there are plentiful rivers and many tributaries of those rivers. Naturally, overtime these rivers shifted their courses', causing the natural landscape of the region to be unsuitable for tangible archaeological evidence and remains.[1] Hence the very weak evidence for a prehistoric human presence in the region.[2] The lack of stones suggests that the early humans in Bengal probably used materials such as wood and bamboo that could not survive in the environment. Human presence during the Neolithic and Chalcolithic eras also seem to be similar with scant evidence.[1] This usually means that archaeological discoveries are almost entirely from the hills around the Bengal delta.[citation needed] Industries of fossil-wood manufacturing blades, scrapers and axes have been discovered in Lalmai, Sitakund and Chaklapunji.[citation needed] These have been connected with similar findings in Myanmar and West Bengal.[citation needed] Large stones, thought to be prehistoric, were constructed in north eastern Bangladesh and are similar to those in India's nearby hills.[citation needed] West Bengal holds the earliest evidence of settled agrarian societies.[3]

Moreover, during the fifth century BCE there was widespread agricultural success for stationery cultures with the emergence of cross-sea trade, some of the earliest polities and many towns. Wari-Bateshwar, was an ancient city within the region and traded with Ancient Rome and Southeast Asia. Archaeologists have discovered coinage, pottery, iron artefacts, bricked road and a fort in Wari-Bateshwar. The findings connote that this city was an administrative hub with industries such as iron smelting and valuable stone beads. The site shows extensive use of clay and bricks, which were most prominent on the walls.[4] Chandraketurgarh in West Bengal is home to some of the most famous terracotta plaques, made by clay depicting deities and scenes of ordinary life and nature.[5] The early coinage unearthed in Wari-Bateshwar and Chandraketugarh were found to be illustrating boats.[6]

The Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW or NBP) was a culture of the Indian Subcontinent lasting between c. 700–200 BCE. It peaked from c. 500 - 300 BCE and coincided with the emergence of the 16 Mahajanapadas of North India and the eventual rise of the Magadhan Dynasties.

Militarily, ancient Bangladesh possessed mighty armies consisting of eighty thousand horsemen, two hundred thousand footmen, eight thousand chariots, and six thousand war elephants. The combined might of the Nanda's and the Gangaridai would then go on to cause Alexander the Great's withdrawal from India. Fearing the prospect of facing other large armies and exhausted by years of campaigning, Alexander's army mutinied at the Hyphasis River (Beas), refusing to march farther east.[7] This river thus marks the easternmost extent of Alexander's conquests.[8]

Ancient regions and divisions

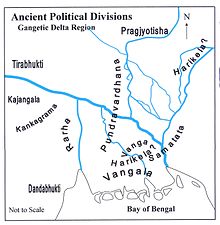

[edit]

| Ancient region | Modern region |

|---|---|

| Pundravardhana | Rajshahi Division and Rangpur Division in Bangladesh; Malda division of West Bengal in India |

| Vanga | Khulna Division and Barisal Division in Bangladesh; West of the Padma river. |

| Samatata | Dhaka Division, Barisal Division and Chittagong Division in Bangladesh |

| Harikela | Sylhet Division, Chittagong Division, Dhaka Division and Barisal Division in Bangladesh |

Emergence of the Janapadas

[edit]

The Janapadas were the realms, republics and kingdoms of the Indian subcontinent during the Vedic period. They surfaced all across the Indian subcontinent and lasted between c. 1100–600 BCE. The Vedic period reached from the late Bronze Age into the Iron Age - from about 1500 BCE to the 6th century BCE. With the rise of sixteen Mahajanapadas ('great janapadas'), most of the states were annexed by more powerful neighbours, although some remained independent.[9] Among some of these independent entities were the Pundra and Vanga Kingdom which were the most eminent kingdoms from the region.

Pundra Kingdom

[edit]The Pundra Kingdom or Pundravardhana emerged during the late Bronze Age around c. 1280 BCE and was the very first documented independent kingdom in the region of Bangladesh. It was mostly known for being the home and birthplace of Ācārya Bhadrabahu. Bhadrabahu was the spiritual teacher of Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Maurya Empire.

24°58′N 89°21′E / 24.96°N 89.35°EMahasthangarh, the ancient capital of Pundravardhana is located 11 km (7 mi) north of Bogra on the Bogra-Rangpur highway, with a feeder road (running along the eastern side of the ramparts of the citadel for 1.5 km) leading to Jahajghata and site museum.[10]

Samatata

[edit]Samatata was an ancient geopolitical division in the east of Bengal. It was located in much of modern-day Bangladesh corresponding to the Chittagong Division, Dhaka Division, Barisal Division and Sylhet division. It also ruled parts northern Arakan (Rakhine State, Myanmar). Samatata's recorded independent dynasties are the Gauda, Bhadra,[11] Khadga, Deva,[12][13] Chandra and Varman dynasties. The Khadgas were originally from Vanga but later conquered Samatata. A Chinese account of the Khadga king Rajabhatta places the royal capital of Karmanta-vasaka (identified with Barakamata village in Cumilla) in Samatata.[14] After the Khadgas, the Devas gained power and started ruling over the kingdom.

Samatata was a center of Buddhist civilisation before the rise of Hinduism and the coming of Islam into the region. Sufi Mostafizur Rahman, an archaelogist believes that the riverside citadel in the ruins of Wari-Bateshwar was the city-state of Sounagoura.[15] The Greco-Roman account of Sounagoura is linked to the kingdom of Samatata. Roman geographer Ptolemy, wrote about a trading post called Souanagoura in the eastern part of the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta.[16] According to Ptolemy Sounagoura was on the banks of the Brahmaputra River. He uses the word emporium which was term used by the Romans to describe a trading colony constructed by Roman merchants. Previously the Brahmaputra River had flowed down from the Himalayas and to the east of Wari-Bateshwar and fusing with the Meghna before reaching the Bengal Delta; however an Earthquake in 1783 caused the river to change its course. Ptolemy places Sounagoura near the old course of the river. Evidence for monetary and urban civilisation before the Mauryan period have been found in excavations in Wari-Bateshwar.[17][18]

Dilip Kumar Chakrabarti, an archaeologist and historian also considers Wari-Bateshwar to be a part of the trans-Meghna region.[20][21] In a book edited by Patrick Olivelle, Chakrabarti states "It appears that Wari-Bateshwar belongs to the Samatata tract. Till now this is the only early historic site reported from this tract, but the very fact that it existed as early as the mid-fifth century BCE in this part of Bangladesh shows the geographical unit of Samatata, although inscriptionally documented in the fourth century CE, has a much earlier antiquity which touches the Mahajanapada period. Secondly, on the basis of the fact that Wari-Bateshwar is a fortified settlement, we argue that in addition to its character as a manufacturing and trading center, it was also an administrative center and most likely to be the ancient capital of the Samatata region".[22]

Samatata was conquered and ruled by both the Mauryan and Gupta Empires. The Maurya Empire declined after the death of emperor Ashoka, and the eastern part of Bengal became the state of Samatata.[23] The rulers of the erstwhile state remain unknown. During the Gupta Empire, the Indian emperor Samudragupta recorded Samatata as a "frontier kingdom" which paid an annual tribute. This was recorded by Samudragupta's inscription on the Allahabad pillar, which states the following in lines 22–23.

{{blockquote|"Samudragupta, whose formidable rule was propitiated with the payment of all tributes, execution of orders and visits (to his court) for obeisance by such frontier rulers as those of Samataṭa, Ḍavāka, Kāmarūpa, Nēpāla, and Kartṛipura, and, by the Mālavas, Ārjunāyanas, Yaudhēyas, Mādrakas, Ābhīras, Prārjunas, Sanakānīkas, Kākas, Kharaparikas and other nations"|Lines 22–23 of the Allahabad pillar inscription of Samudragupta (r.c.350-375 CE).[24]

Vanga Kingdom

[edit]

The Vanga Kingdom was a powerful seafaring nation of Ancient Bengal with their capital, Kotalipara located in present day Dhaka. It was established during the beginning of the late Vedic period was destablished c. 340 BCE. They had overseas trade relations with Java, Sumatra and Siam (modern day Thailand). According to Mahavamsa, the Vanga prince Vijaya Singha conquered Lanka (modern day Sri Lanka) in 544 BC and gave the name "Sinhala" to the country.[25] The Vanga people were also said to have established a settlement in Cochinchina, naming the settlement after their native name[25]The Vanga people were said to have migrated to Siam too, however this claim lacks any evidence.[verification needed]

Kurukshetra War

[edit]The Kurukshetra War, c. 400 BCE - c. 500 BCE, is a war described in the Hindu epic poem Mahabharata, rising from a struggle between two groups of cousins, the Kauravas and the Pandavas to acquire the throne of Hastinapura. The Vanga Kingdom sided with the Kauravas. In modern times the Kurukshetra war has become recognised as mythology as the historical accuracy of the Kurukshetra War and the Mahabharata is uncertain and unclear.

Vangas sided with Duryodhana in the Kurukshetra War (8:17) along with the Kalingas. They are mentioned as part of the Kaurava army at (7:158). Many foremost of combatants skilled in elephant-fight, belonging to the Easterners, the Southerners, the Angas, the Vangas, the Pundras, the Magadhas, the Tamraliptakas, the Mekalas, the Koshalas, the Madras, the Dasharnas, the Nishadas united with the Kalingas (8:22). Satyaki, pierced the vitals of the elephant belonging to the king of the Vangas (8:22). Behind Duryodhana proceeded the ruler of the Vangas, with ten thousand elephants, huge as hills, and each with juice trickling down (6:92). The ruler of the Vangas (Bhagadatta) mounting upon an elephant huge as a hill, drove towards the Rakshasa, Ghatotkacha. On the field of battle, with the mighty elephant of great speed, Bhagadatta placed himself in the very front of Duryodhana's car. With that elephant he completely shrouded the car of thy son. Beholding then the way (to Duryodhana's car) thus covered by the intelligent king of the Vangas, the eyes of Ghatotkacha became red in anger. He ruled that huge dart, before upraised, at that elephant. Struck with that dart hurled from the arms of Ghatotkacha, that elephant, covered with blood and in great agony, fell down and died. The mighty king of the Vangas, however, quickly jumping down from that elephant, alighted on the ground (6:93).

Prince Vijaya

[edit]Prince Vijaya was born in the Vanga Kingdom and is one of the most notable figures of the Vanga Kingdom. He is also known in Sri Lankan History for being the first King of Sri Lanka. Prince Vijaya was made prince regent by his father, but the young prince and his band of followers would go on to become notorious for their violent deeds. With multiple complaints from Vijaya's father failing, many citizens opted for Vijaya's death. King Sinhabahu then expelled Vijaya and 700 of his followers from the kingdom. The prince left the Kingdom of Vanga and would eventually reach the northern tip of the island of Sri Lanka where he would establish the Kingdom of Tambapanni.[26] The descendants of Prince Vijaya (from the House of Vijaya) would rule the island for next 500 years and also go on to establish the Kingdom of Upatissa Nuwara and finally the Anuradhapura Kingdom.[27][28]

Prince Vijaya's party of several hundred landed in Sri Lanka, were split on the journey. The men, women and children were on separate ships. Vijaya and his followers landed at a place called Supparaka; the women landed at a place called Mahiladipaka present day (Maldives), and the children landed at a place called Naggadipa. Vijaya eventually made it to the island of Lanka.

Oversea Settlements of Vanga

[edit]The Vanga Kingdom was known for its superior naval fleets and naval supremacy. According to the Mahabarata (major Indian epic) the Vanga Kingdom also colonised territory outside of mainland India. While this claim is not very likely it cannot be ignored completely because of the instances the Vanga Kingdom having oversea settlements and the special case of Prince Vijaya's conquest of the island of Lanka.

This can be observed with the supposed Vanga settlements in the island of Mahiladipaka in the Maldives and Prince Vijaya's conquests of Lanka when the women of Prince Vijaya's party went astray and landed at Mahiladipaka.[citation needed] There has also been findings of Vanga settlements in Southeast Asia. Most notably in Champa (present-day Vietnam), where a settlement was founded in Cochinchina. The settlement was named after a native Bengali name[25]

Gangaridai and the Nanda Dynasty

[edit]Independent Gangaridai

[edit]Not much is known about the independent state of Gangaridai and when it was independent, however renowned Bengali historian, Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay, noted that during the rule of Chandragupta Maurya, the state of Gangaridai was independent.[29] The state of Gangaridai was established c. 300 BCE.

Establishment of the Nanda Dynasty

[edit]

The origins of the Nanda dynasty vary amongst historians however one view regarding the origins of the Nanda dynasty is D.C Sircar and R.C Majumdar and their argument that the Nanda Dynasty was of Gangaridae (Bengali) origin. In recent times R.C Majumdar has been categorised as nationalistic and while this may have affected his works, it doesn't take away the possibilty of Gangaridae origin as his argument is the same as D.C Sircar's argument and the University of Sri Venkatesvara.[30][31]

The Nanda's, are represented as the lord of both "Prasioi and the Gangaridai" or of Gangaridai alone. The description of Prasioi was a general name for the people of Eastern India, so the specific mention of Gangaridai attaches significance. The importance of Gangaridai or the Vanga people (Lower Bengal) may be explained by the suggestion of the Nanda dynasty belonging to them.[30][31]

The idea of the Bengali origin of the Nanda's can also be observed through Greek accounts of Xandrames (Greek for 'Nanda'). As Diodorus explicitly states, Plutarch affirms and Arrian evidently implies, Bengal had conquered Magadha.[31] This view is also compatible with the Puranic account and would explain the low position of these kings in the Puranas as Bengal was outside the domain of Aryan Culture during this time.[32]

Alexanders the Great's withdrawal

[edit]

East of Porus's kingdom, near the Ganges River, was the Nanda Empire of Magadha and the Gangaridai Empire of the Bengal region in the Indian subcontinent. Fearing the prospect of facing other large armies and exhausted by years of campaigning, Alexander's army mutinied at the Hyphasis River (Beas), refusing to march farther east.[7]

Alexander tried to persuade his soldiers to march farther, but his general Coenus pleaded with him to change his opinion and return. Alexander eventually agreed and turned south, marching along the Indus. Along the way his army conquered the Malhi (in modern-day Multan) and other Indian tribes; while besieging the Mallian citadel, Alexander suffered a near-fatal injury when an arrow penetrated his armor and entered his lung.[33][34]

"As for the Macedonians, however, their struggle with Porus blunted their courage and stayed their further advance into India. For having had all they could do to repulse an enemy who mustered only twenty thousand infantry and two thousand horse, they violently opposed Alexander when he insisted on crossing the river Ganges also, the width of which, as they learned, was thirty-two furlongs [6.4 km], its depth one hundred fathoms [180 m], while its banks on the further side were covered with multitudes of men-at-arms and horsemen and elephants. For they were told that the kings of the Ganderites and Praesii were awaiting them with eighty thousand horsemen, two hundred thousand footmen, eight thousand chariots, and six thousand war elephants."[35]

Trade

[edit]Southwestern Silk Road

[edit]The southwestern route is believed to be the Ganges/Brahmaputra Delta, which has been the subject of international interest for over two millennia. Strabo, the 1st-century Roman writer, mentions the deltaic lands: "Regarding merchants who now sail from Egypt... as far as the Ganges, they are only private citizens." His comments are interesting as Roman beads and other materials are being found at Wari-Bateshwar ruins, the ancient city with roots from much earlier, before the Bronze Age, presently being slowly excavated beside the Old Brahmaputra in Bangladesh. Ptolemy's map of the Ganges Delta, a remarkably accurate effort, showed that his informants knew all about the course of the Brahmaputra River, crossing through the Himalayas then bending westward to its source in Tibet. It is doubtless that this delta was a major international trading center, almost certainly from much earlier than the Common Era. Gemstones and other merchandise from Thailand and Java were traded in the delta and through it. Chinese archaeological writer Bin Yang and some earlier writers and archaeologists, such as Janice Stargardt, strongly suggest this route of international trade as Sichuan–Yunnan–Burma–Bangladesh route. According to Bin Yang, especially from the 12th century, the route was used to ship bullion from Yunnan (gold and silver are among the minerals in which Yunnan is rich), through northern Burma, into modern Bangladesh, making use of the ancient route, known as the 'Ledo' route. The emerging evidence of the ancient cities of Bangladesh, in particular Wari-Bateshwar ruins, Mahasthangarh, Bhitagarh, Bikrampur, Egarasindhur, and Sonargaon, are believed to be the international trade centers in this route.[36][37][38]

Muslin

[edit]Bengal has manufactured textiles for many centuries, as recorded in ancient hand-written and printed documents. Muslin finds mention in Megasthenes’ writings, a Greek envoy to the court of Chandragupta Maurya in the 4th century BC, and is supposed to be the fabric worn by the figurines of the 2nd century BC found at Chandraketugarh. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea written between 40 and 70 AD mentions Arab and Greek merchants trading between India and the Red Sea port of Aduli (in present-day Eritrea), Egypt and Ethiopia. The Charyapada of the 10th century, written on palm leaves, contain a complete description of the process of weaving muslin. Cloths including muslin were exchanged for ivory, tortoiseshell and rhinoceros-horn at that time. Muslin was traded from Barygaza – an ancient port of India located in Gujarat – to different parts of Indian subcontinent before European merchants came to India.[39]

The earliest specimen of Bengali fine cotton cloth (like muslin) was found in Egypt as a mummy shroud around 2000 BC. The first commercial mention of Indian cotton is found in The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (63 AD). The book mentions the export of fine cotton textiles from different parts of India to Europe. The eastern (Bengal) and north-western regions of India produced large quantities of fine cotton cloth, but Bengal cotton cloth was superior in quality. According to the text, European merchants procured fine cotton fabrics from the Gange port of Bengal. In this text, broad and smooth cotton cloth is referred to as Monachi and the finest cotton cloth is called Gangetic. A kingdom called 'Ruhma' is found in the Sulaiman al-Tajir written by the 9th century Arab merchant Sulaiman, where fine cotton fabrics was produced. There were cotton fabrics so fine and delicate that a single piece of cloth could be easily moved through the ring. Very fine cotton cloth was made in Mosul in the 12th century and later. Arab traders carried it to Europe as a commodity, and enchanted Europeans called it muslin; since then the very fine and beautiful cotton cloth came to be known as muslin. In 1298 AD, Marco Polo described in his book The Travels that muslin is made in Mosul, Iraq.[40] Ibn Battuta, a Moroccan traveler who came to Bengal in the middle of the 14th century, praised the cotton cloth made in Sonargaon in his book The Rihla. Chinese writers who came to Bengal in the fifteenth century praised cotton cloth.

Muslin, a Phuti carpus cotton fabric of plain weave, was historically hand woven in the areas of Dhaka and Sonargaon in Bangladesh and exported for many centuries.[41] The region forms the eastern part of the historic region of Bengal. The muslin trade at one time made the Ganges delta and what is now Bangladesh into one of the most prosperous parts of the world. Of all the unique elements that must come together to manufacture muslin, none is as unique as the cotton, the famous "phuti karpas", scientifically known as Gossypium arboreum var. neglecta.[42] Dhaka muslin was immensely popular and sold across the globe for millennia. Muslin from "India" is mentioned in the book Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, authored by an anonymous Egyptian merchant around 2,000 years ago, it was appreciated by the Ancient Greeks and Romans, and the fabled fabric was the pinnacle of European fashion in the 18th and 19th century. Production ceased sometime in the late 19th century, as the Bengali muslin industry could no longer compete against cheaper British-made textiles.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Baxter 1997, p. 12.

- ^ Willem 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Willem 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Willem 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Willem 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Willem 2009, p. 19.

- ^ a b Kosmin 2014, p. 34.

- ^ Tripathi 1999, pp. 129–30.

- ^ Misra 1973, p. 18.

- ^ Hossain 2006, p. 14-15.

- ^ Chakrabarti, Amita (1991). History of Bengal, C. A.D. 550 to C. A.D. 750. University of Burdwan. p. 122.

- ^ Sein, U. Aung Kyaw (May 2011). Vesāli: Evidences of Early Historical City in Rakhine Region (MA). University of Yangoon.

- ^ Singer, Noel F. (2008). Vaishali and the Indianization of Arakan. New Delhi: APH Publishing Corp. ISBN 978-81-313-0405-1. OCLC 244247519.

- ^ Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Samatata". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- ^ Kamrul Hasan Khan, back from Wari-Bateswar (1 April 2007). "The Daily Star Web Edition Vol. 5 Num 1008". Archive.thedailystar.net. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "First, in his list of towns in transgangetic India Ptolemy mentions a place called Souanagoura which has been identified with modern Sonargaon" Excavation at Wari-Bateshwar: A Preliminary Study, Enamul Haque – 2001

- ^ "A Family's Passion – Archaeology Magazine". Archaeology.org. Archived from the original on 24 November 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Shahnaj Husne Jahan X close (2010). "Archaeology of Wari-Bateshwar". Ancient Asia. 2: 135. doi:10.5334/aa.10210.

- ^ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 145, map XIV.1 (d). ISBN 0226742210. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- ^ Dilip K. Chakrabarti (1 June 1997). Colonial Indology: sociopolitics of the ancient Indian past. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-215-0750-9.

- ^ Dilip K. Chakrabarti (1998). The issues in East Indian archaeology. Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 978-81-215-0804-9.

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (13 July 2006). Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1.

- ^ Douglas A. Phillips; Charles F. Gritzner (2007). Bangladesh. Infobase Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4381-0485-0.

- ^ a b Fleet 1888, p. 6-10.

- ^ a b c The Modern Review, p. 111-112.

- ^ Mittal 2006, p. 405.

- ^ Ratnatunga.

- ^ The Mahavamsa, p. 06.

- ^ Gangaridai.

- ^ a b Sri Venkatesvara University 1979, p. 33.

- ^ a b c Sircar 1984, p. 5.

- ^ Majumdar 1925, p. 11.

- ^ Tripathi 1999, pp. 137–38.

- ^ Dodge 1890, p. 604-605.

- ^ Plutarch 1919.

- ^ Yang, Bin. (2008). Between Winds and Clouds: The Making of Yunnan. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ "History and Legend of Sino-Bangla Contacts". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. 28 September 2010. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- ^ "Seminar on Southwest Silk Road held in City". Holiday. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- ^ Ashmore, Sonia (2012). Muslin (Sonia Ashmore), Page 11. V&A Publishing. ISBN 9781851777143. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- ^ Marco Polo 1937, p. 28.

- ^ "Muslin", Encyclopædia Britannica, archived from the original on 4 May 2015, retrieved 12 January 2025

- ^ "Textile hub Bangladesh revives muslin, the forgotten elite fabric". Al Jazeera English. 9 March 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

Muslin can't be woven without Phuti carpus cotton.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baxter, Craig (1997). Bangladesh: From A Nation to a State. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-813-33632-9.

- Willem, Schendel (2009). A History of Bangladesh. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511997419.

- Richard, M. Eaton (31 July 1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2025.

- The Mahavamsa. "The Coming of Vijaya - the Sinhalese epic". Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2025.

- Misra, Sudama (1973). Janapada state in ancient India. Vārāṇasī: Bhāratīya Vidyā Prakāśana.

- Hossain, Md. Mosharraf (2006). Mahasthan: Anecdote to History. Dibyaprakash. ISBN 984-483-245-4.

- Mittal, J.P (2006). History of Ancient India (A New Version) Volume 2. Atlantic. ISBN 9788126906161.

- The Modern Review. Ramananda Chatterjee (ed.). "The Modern Review Volume 12".

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Ratnatunga, Rhajiv. "Chapter I The Beginnings; And The Conversion To Buddhism". lakdiva.org.

- M. Senaveratna, John (2000). Royalty in Ancient Ceylon: During the Period of the "great Dynasty". Colombo, Sri Lanka: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1530-1. Retrieved 9 January 2025.

- Gangaridai. "The Historic State of Gangaridai". Bangladesh.com. Archived from the original on 24 December 2024.

- Sri Venkatesvara University, Oriental Research Institute (1979). Sri Venkateswara University Oriental Journal Volumes 21–22.

- Sircar, D.C. (1984). Journal of Ancient Indian History, Vol-14.

- Majumdar, R.C (1925). The early history of Bengal (PDF). Oxford University Press.

- Plutarch (1919). Perrin, Bernadotte (ed.). Plutarch, Alexander. Perseus Project. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0. Retrieved 9 January 2025.

- Tripathi, Rama Shankar (1999). History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-0018-2. Retrieved 9 January 2025.

- Dodge, Theodore Ayrault (1890). Alexander. Great captains. Vol. 2. Houghton Mifflin.

- Marco Polo (1937). The most noble and famous travels of Marco Polo, together with the travels of Nicoláo de' Conti. London, A. and C. Black.

- Fleet, John Faithfull (1888). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Vol. 3.