Battle of Lake Borgne

| Battle of Lake Borgne | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

British and American Gunboats in Action on Lake Borgne, 14 December 1814, Thomas Lyde Hornbrook | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 42 rowboats |

5 gunboats 1 sloop 1 schooner | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

94 killed and wounded[1] 1 rowboat sunk [2] |

41 killed and wounded[3] 6 boats' crews captured 5 gunboats captured 1 sloop captured 1 schooner scuttled | ||||||

The Battle of Lake Borgne was a coastal engagement between the Royal Navy and the U.S. Navy in the American South theatre of the War of 1812. It occurred on December 14, 1814 on Lake Borgne. The British victory allowed them to disembark their troops unhindered nine days later[4] and to launch an offensive upon New Orleans on land.[5]

Background

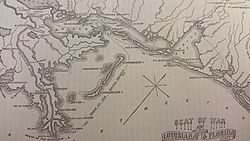

[edit]In August 1814, Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane had convinced the Admiralty that a campaign against New Orleans would weaken American resolve against Canada, and hasten a successful end to the war.[a] In the winter of 1814, the British had the objective of gaining control of the entrance of the Mississippi, and to challenge the legality of the Louisiana Purchase.[7] To this end, an expeditionary force of about 8,000 troops under General Edward Pakenham had arrived in the Gulf Coast, to attack New Orleans.[8] An anonymous letter sent from Pensacola, dated December 5 and addressed to Commodore Daniel Patterson warned him of this imminent threat,[9] and was received on December 7.[10] Patterson dispatched Lieutenant Thomas ap Catesby Jones and a small flotilla to wait outside of the Rigolets heading eastward, towards the passes Mariana and Christiana (marked on Lossing's map, close to Cat Island), to watch the movements of the British vessels.[11]

The American force consisted of five Jeffersonian gunboats – No. 156, No. 163, No. 5, No. 23, and No. 162 – the schooner USS Sea Horse with Sailing-Master Johnson commanding, and a sloop-of-war, USS Alligator, serving as a tender.[12] Gunboat No. 156, the flagship of the squadron, mounted one long 24-pounder, four 12-pounder carronades,[13] and four swivel guns. She had a crew of over forty men.[14]

Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, British Commander-in-Chief of the North American Station, ordered HMS Seahorse, Armide and Sophie from Pensacola to the anchorage within Ship Island (Mississippi).[15] This location, known today as Bayou Bienvenue, at the head of the lake, situated 60 miles (97 km) from the troopship anchorage of Cat Island, was to be the disembarkation point for the British soldiers. On December 8, the three British vessels reported that as they passed Cat Island, Mississippi, two American gunboats had fired at them. Furthermore, lookouts on the masts had seen three more gunboats.[14] It would not be possible to proceed with the disembarkation until this squadron of five gunboats, in the shallow waters of the inlet Lake Borgne, was destroyed.[3]

Cochrane put all the rowboats of the British fleet under the command of Commander Nicholas Lockyer of Sophie, with orders to pursue the American flotilla,[15] in waters too shallow for an attack by a ship of the line.[b][17] The British deployed forty launches and barges with one 12, 18 or 24 pounder carronade each, two further launches with a long 9 pounder and a long 12 pounder respectively, as well as three unarmed gigs.[13] The force consisted of some 980 sailors and Royal Marines.[18] The largest number of men embarked in any one of the barges was 31.[19]

Jones's squadron headed back in the direction of the Rigolets, mooring at Bay St Louis on December 10. The following day, they prepared their boats to make an attack. On December 12 the squadron arrived at Cat Island, but found the overwhelming strength of the British would have been disadvantageous to the gunboats, so they returned in the direction of the Rigolets, and the fort at Petit Coquilles.[21] Owing to the strong current, they were only able to get as far as the channel between the mainland and Malheureux Island on December 13 (to the south of the modern day settlement of Ansley, Mississippi).[22] Jones had been ordered by Patterson to position his gunboats across Pass Christiana, then at the mouth of Lake Borgne, then fall back to the Rigolets to make a stand.[23][17]

At night on December 12, the British rowboats, under Lockyer, set off to enter Lake Borgne, to attack the gunboat squadron.[13] Jones sighted the British rowboats on December 13 at 10:00am believing them to be disembarking troops, advancing in the direction of Pass Christian and then stopping. When he saw their route at 2:00pm, advancing past Pass Christian without stopping, he realized they were heading to attack his gunboats.[13][24] The shallow waters caused Jones issues, three of his gunboats being in 12 or 18 inches of water less than their draught, which was resolved by the flood tide at 3:30pm.[13][25]

The first contact was between three of Lockyer's launches and the schooner Sea Horse on December 13 at 3:45pm. At 2:00pm she had been sent to remove, or failing that to destroy, a stores dump at Bay St. Louis in order to prevent its capture by British forces. The schooner, with the protection of two land-based 6-pounder cannon,[13] saw off three approaching launches with grapeshot, who initially retired out of range. Sea Horse faced a subsequent rowboat attack with four more launches as reinforcements, commanded by Captain Samuel Roberts of HMS Meteor.[24] This renewed attack was 'repulsed after sustaining for nearly half an hour a very destructive fire.'[3] In the face of superior numbers, the Sea Horse was scuttled and the store was set alight, an explosion occurring at 7:30pm with a large fire being visible thereafter.[13][26][25] Jones subsequently confirmed that he had sanctioned Johnson to destroy his schooner to prevent it being captured.[27]

At 8:00pm, Lockyer rested his boat crews, who had been rowing against the flow of the tide.[25]

Battle

[edit]

After rowing for about thirty-six hours,[14] the British approached the five American vessels drawn up in line abreast to block the channel between Malheureux Island and Point Claire on the mainland. At daybreak, Jones noticed the British rowboats nine miles to the east.[29] As the British advanced, they spotted Alligator, immediately sent a few rowboats under Roberts to cut her off and the British quickly captured her at 9:30am.[13] At 10 o'clock on the morning of December 14, the British boats had closed to within long gunshot by St. Joseph's Island.[14] At this point Lockyer ordered the boats' crews to breakfast.[14] Lockyer formed the boats into three divisions. He took command of the first, gave Commander Henry Montresor of Manly command of the second, and Roberts of Meteor command of the third. When the British had finished their breakfast they returned to their oars and pulled up to the line of American gunboats. The main battle came at 10:39 am.[13] The British were rowing against a strong current and under a heavy fire of round and grapeshot.[14]

The American sailors killed or wounded a number of the rowboat crews in the process, including most of the men in Lockyer's boat.[14] Eventually the range closed and the British sailors and marines began to board the American vessels. At 11:50am Lockyer personally boarded Gunboat No. 156, Jones's vessel.[3] Both Lockyer and Jones sustained severe wounds. One rowboat from Tonnant, commanded by Lieutenant James Barnwell Tattnall grappled the gunboat and was sunk,[2] all of its boarding party transferred to the other rowboats.[30][14] Jones states that at 12:10pm the British captured Gunboat No. 156 and turned her guns against her sister ships.[13] The gunboat fired her broadsides and assisted the capture of the remaining American craft. One by one, the British took the other four American gunboats. The engagement was over at 12:30pm.[3] Lockyer had hypothesised that boarding and capturing the rest of the American flotilla took five minutes, rather than the twenty minutes in Jones's account.[14]

Aftermath

[edit]

The engagement lasted about two hours, though the actual hand-to-hand combat was short. Whilst the British outnumbered the American seamen, Roosevelt does note the advantage Jones's flotilla had in defense, being stationary, having some long heavy guns and boarding nettings. This was offset by two of the five gunboats (No.156 commanded by Jones, and No.163 commanded by Ulrick)[25] having drifted out of line.[31]

The Americans lost their entire flotilla of five gunboats and crew,[13] of whom 41 were killed or wounded.[3] Lockyer states the five gunboats were each crewed by 45 men, for a total of 225, whereas Jones gives a lower figure for a total of 182 men in the five gunboats.[3] Jones was made a prisoner of war for three months and would later be decorated for his bravery in this engagement. The British casualties were 94 killed and wounded. The casualties were from the following vessels: Tonnant, Norge, Bedford, Royal Oak, Ramillies, Armide, Cydnus, Seahorse, Trave, Sophie, Belle Poule, Gorgon, Meteor.[14] American claims that at least two British boats sunk and over 300 casualties were inflicted, as Jones claimed,[13][21] are disputed.[32]

In all, the six captured vessels of Jones's squadron comprised a loss of 245 men, sixteen long guns, fourteen carronades, two howitzers and twelve swivel guns, as reported by Lockyer.[14] Cochrane rated the captured flotilla as the equivalent of a 36-gun frigate and appointed Lockyer to its command as soon as his wounds permitted.[15] Montresor took command pro tem; in March 1815, Lockyer received promotion to post captain.[33]

The British took the five gunboats into service under the names Ambush (or Ambush No. 5), Firebrand, Destruction, Harlequin and Eagle. Several of these vessels remained in Royal Navy service into June 1815, and at least one perhaps beyond.[34][c] As well as the warships providing men for the boats, there were sailors from the troopships Alceste, Belle Poule, Diomede and Gorgon. The following troopships were nearby, and thus eligible for prize money: Bucephalus, Dictator, Dover, Fox, Hydra and Thames.[d][36]

Lake Borgne would become the landing zone for British forces preparing to attack New Orleans. After the population of the city learned of the engagement on Lake Borgne, panic overtook some inhabitants of New Orleans; so Andrew Jackson declared martial law on December 15.[37][38][5]

The loss of the gunboats meant that Jackson had no means of surveillance of the British, and it is noted that he did not deploy scouts as a substitute.[39]

One unintended consequence is that the gunboat crews in captivity were able to mislead the British as to Jackson's strength in numbers, when they were questioned.[40][41]

At the end of January 1815, the prisoners of war were transported to the Caribbean in HMS Ramillies.[41] In February 1815, following news of ratification of the peace treaty, HMS Nymphe was sent to Jamaica, to fetch the prisoners taken at Lake Borgne, and to repatriate the prisoners.[42][43]

Although Jones's squadron never made it as far as the fort at Petit Coquilles, it was decided to improve the coastal defences with the creation of Fort Pike commencing in 1819 to replace the earlier fort. It was the first of three forts to be constructed in Louisiana under the postwar "Third System", along with Fort Jackson, Louisiana and Fort Livingston, Louisiana.[44]

The engagement itself was not referred to as a "battle" in the literature of the 19th century.[8][2] Hornbrook's painting from the 1840s uses the word 'action' in its title.[45] Secondary sources in the 20th century do refer to the 'Battle of Lake Borgne'.[46][47]

Medal

[edit]In 1847 the Admiralty initiated the Naval General Service Medal. The clasps covered a variety of actions, from boat service to single-ship actions, to larger naval engagements, including major fleet actions. The engagement at Lake Borgne was deemed a boat service worthy enough of recognition by a clasp, and appears on the list of clasps for boat service during the War of 1812. The Admiralty issued a clasp (or bar) marked "14 Dec. Boat Service 1814" to surviving combatants who claimed the clasp.[e][48] This was the largest Boat Action for which the Naval General Service Medal was granted. In all, 205 survivors claimed it.[26]

See also

[edit]Notes and citations

[edit]Notes

- ^ Gene Allen Smith makes reference to a letter from the Secretary of the Admiralty to Cochrane dated August 10, 1814, archive reference WO 1/141. A copy of this document is accessible at The Historic New Orleans Collection, via microfilm. Smith also mentions how several Royal Navy officers had suggested the idea of attacking Louisiana from 1813 onwards.[6]

- ^ William James comments on the geography, with the benefit of hindsight. 'But the flatness of the coast is everywhere unfavourable for the debarkation of troops, and the bays and inlets being all obstructed by shoals or bars, no landing can be effected, but by boats, except up the Mississippi; and that has a bar at its mouth, which shoals to 13 or 14 feet water.'[16]

- ^ A first-class share of the prize money was worth £34 12s 9¼d; a sixth-class share, that of an ordinary seaman, was worth 7s 10¾d.[35]

- ^ 'Notice is hereby given to the officers and companies of His Majesty's ships Aetna, Alceste, Anaconda, Armide, Asia, Bedford, Belle Poule, Borer, Bucephalus, Calliope, Carron, Cydnus, Dictator, Diomede, Dover, Fox, Gorgon, Herald, Hydra, Meteor, Norge, Nymphe, Pigmy, Ramillies, Royal Oak, Seahorse, Shelburne, Sophie, Thames, Thistle, Tonnant, Trave, Volcano, and Weser, that they will be paid their respective proportions of prize money.' [35]

- ^ The 'Names of Ships for which Claims have been proved' are as follows: warships Tonnant, Norge, Royal Oak, Ramillies, Bedford, Armide, Cydnus, Trave, Seahorse, Sophie, Meteor; troopships Gorgon, Diomede, Alceste, Belle Poule

Citations

- ^ Casualty returns within "No. 16991". The London Gazette. 9 March 1815. pp. 446–449.

- ^ a b c Clowes (1901), p. 150.

- ^ a b c d e f g Roosevelt (1900), p. 77.

- ^ Remini (1999), pp. 62–64.

- ^ a b Remini (1999), p. 66.

- ^ Smith (2008), p. 89.

- ^ Grodzinski (ed) (2011), p.1

- ^ a b Roosevelt (1900), p. 73.

- ^ Latour (1816), p. 57.

- ^ James (1818), p. 57.

- ^ Latour (1816), pp. 57–58.

- ^ Roosevelt (1900), pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Letter from Jones to Patterson dated 12 March 1815, within Brannan (ed). pp.487-490

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Letter from Lockyer to Cochrane dated 18 December 1814, reproduced in "No. 16991". The London Gazette. 9 March 1815. pp. 446–449.

- ^ a b c Letter from Cochrane to Admiralty dated 16 December 1814, reproduced in "No. 16991". The London Gazette. 9 March 1815. pp. 446–449.

- ^ James (1818), p. 347.

- ^ a b Reilly (1976), p. 223.

- ^ James (1902), p. 232.

- ^ James (1818), p. 352.

- ^ "Battle of Lake Borgne". Louisiana Maritime Museum. 21 June 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ a b Court martial of inquiry commenced May 15, to investigate the conduct of officers and seamen on December 14, reproduced in Latour (1816), appendix LXII, pp.cxxxii-cxxxv

- ^ Latour (1816), p. 59.

- ^ Daughan (2011), p. 378.

- ^ a b Reilly (1976), p. 224.

- ^ a b c d Daughan (2011), p. 379.

- ^ a b Hayward, Birch & Bishop (2006), pp. 133–134.

- ^ Brown (1969), p. 78.

- ^ Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 1026. ISBN 9780665291364.

- ^ Roosevelt (1900), p. 74.

- ^ James (1818), pp. 350–351.

- ^ Roosevelt (1900), p. 75.

- ^ James (1818), pp. 350–352.

- ^ Marshall (1830), pp.2-7

- ^ Paullin and Paxson (1914), p.436.

- ^ a b "No. 17730". The London Gazette. 28 July 1821. p. 1561.

- ^ "Lake Borgne 14 Dec 1814 and prize money eligibility". Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ James (1818), p. 354.

- ^ Declaration of martial law dated December 15, reproduced in Latour (1816), appendix XXI, p.xxxix

- ^ Daughan (2011), pp. 380–381.

- ^ Daughan (2011), p. 381.

- ^ a b Smith (2000), p. 30.

- ^ James (1818), p. 574.

- ^ Hughes & Brodine (2023), p. 1033-1034.

- ^ Coleman (2005), p. 136.

- ^ "British and American Gunboats in Action on Lake Borgne, 14 December 1814". Caird Collection. National Maritime Museum, Royal Museums Greenwich.

- ^ Reilly (1976), p. 225.

- ^ Brown (1969), p. 77.

- ^ "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 247.

- Bibliography

- Brannan, John, ed. (1823). Official letters of the military and naval officers of the United States : during the war with Great Britain in the years 1812, 13, 14, & 15. Washington, D.C.: Way & Gideon. OCLC 1083481275.

- Brown, Wilburt S (1969). The Amphibious Campaign for West Florida and Louisiana, 1814–1815. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-5100-0.

- Clowes, Sir William (1901). The Royal Navy: Vol. 6: A History – From the Earliest Times to 1900. S. Low, Marston and Co. ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

- Coleman, Elaine (2005). Louisiana Haunted Forts. Lanham MD: Taylor Trade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-46-170909-1.

- Daughan, George C. (2011). 1812: The Navy's War. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02046-1.

- Grodzinski, John, ed. (September 2011). "Instructions to Major-General Sir Edward Pakenham for the New Orleans Campaign". The War of 1812 Magazine (16).

- Hayward; Birch; Bishop (2006). British Battles and Medals (7th ed.). London: Spink. ISBN 1-902040-77-5.

- Hughes, Christine F.; Brodine, Charles E., eds. (2023). The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History, Vol. 4. Washington: Naval Historical Center (GPO). ISBN 978-1-943604-36-4.

- James, William (1818). A full and correct account of the military occurrences of the late war between Great Britain and the United States of America; with an appendix, and plates. Volume II. London: Printed for the author and distributed by Black et al. OCLC 2226903.

- James, William (1902) [1837]. The naval history of Great Britain (1813–1827). Vol. 6 (New six volume ed.). London: Macmillan.

- Latour, Arsène Lacarrière (1816). Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana in 1814–15, with an Atlas. Translated from French into English by H.P. Nugent. Philadelphia: John Conrad and Co. OCLC 40119875.

- Marshall, John (1830). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. sup, part 4. London: Longman and company. p. 2.

- Paullin, Charles Oscar; Paxson, Frederic Logan (1914). Guide to the materials in London archives for the history of the United States since 1783. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington. OCLC 1112813591.

- Reilly, Robin (1976) [1974], The British at the gates – the New Orleans campaign in the War of 1812, London: Cassell, OCLC 839952

- Remini, Robert V. (1999). The Battle of New Orleans. New York: Penguin Putnam, Inc. ISBN 0-670-88551-7.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1900). The Naval War of 1812. Vol. II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

- Smith, Gene A. (2000). Thomas ap Catesby Jones. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-848-5.

- Smith, Gene A. (2008). "Preventing the "Eggs of Insurrection" from Hatching: The U.S. Navy and Control of the Mississippi River, 1806-1815" (PDF). Northern Mariner. issue Nos. 3-4, (July–October 2008). 18 (3–4). The Canadian Nautical Research Society: 79–91. doi:10.25071/2561-5467.355. S2CID 247349162. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

External links

[edit]- Keyes, Pam (30 December 2014). "Patterson's Mistake: the Battle of Lake Borgne Revisited". www.historiaobscura.com/. Retrieved 19 December 2021.