Board wargame

| Part of a series on |

| Wargames |

|---|

|

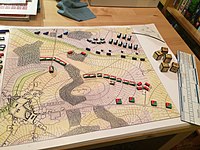

A board wargame is a wargame with a set playing surface or board, as opposed to being played on a computer or in a more free-form playing area as in miniatures games. The modern, commercial wargaming hobby (as distinct from military exercises, or war games) developed in 1954 following the publication and commercial success of Tactics.[1] The board wargaming hobby continues to enjoy a sizeable following, with a number of game publishers and gaming conventions dedicated to the hobby both in the English-speaking world and further afield.[citation needed]

In the United States, commercial board wargames (often shortened to "wargames" for brevity) were popularized in the early 1970s. Elsewhere, notably Great Britain where miniatures had evolved its own commercial hobby, [citation needed] a smaller following developed. The genre is still known for a number of common game-play conventions (or game mechanics) that were developed early on.

The early history of board wargaming was dominated by The Avalon Hill Game Company, while other companies such as SPI also gained importance in the history of the genre.

Overview

[edit]Wargames exist in a range of game complexities. Some are fundamentally simple (often called "beer-and-pretzel games") whereas others attempt to simulate a high level of historical realism ("consim"—short for 'conflict simulation'). [citation needed] These two trends are also at the heart of long-running debates about "realism vs. playability".[2] Because of the subject matter, games considered 'simple' by wargamers can be considered 'complex' to non-wargamers, especially if they have never run into some of the concepts that most wargames share, and often assume some familiarity with. [citation needed]

Wargames tend to be representational, with many using soldier-shaped pieces on a map-like board; as such, they may colloquially be called "dudes on a map" games.[3] Generally, they depict a fairly concrete historical subject (such as the Battle of Gettysburg, one of several popular topics in the genre), but it can also be extended to non-historical ones as well. The Cold War provided fuel for many games that attempted to show what a non-nuclear (or, in a very few cases, nuclear) World War III would be like, moving from a re-creation to a predictive model in the process. Fantasy and science fiction subjects are sometimes not considered wargames because there is nothing in the real world to model; however, conflict in a self-consistent fictional world lends itself to exactly the same types of games and game designs as does military history.[citation needed]

While there is no direct correlation, the more serious wargames tend towards more complex rules with possibilities for more calculation and computation of odds, more exceptions (generally to reproduce unique historical circumstances), more available courses of action, and more detail or "chrome". [citation needed] The extreme end of this tendency are considered "monster games", which typically consist of a large subject represented on small scale.[4] A good example of this would be Terrible Swift Sword, which tracks individual regiments in the Battle of Gettysburg, instead of the more common scale of brigades.[4] These games typically have a combined playing surface (using several map sheets) larger than most tables, and thousands of counters.

Wargames tend to have a few fundamental problems. [citation needed] Notably, both player knowledge and player action are much less limited than what would be available to the player's real-life counterparts. Some games have rules for command and control and fog of war, using various methods. These mechanisms can be cumbersome and onerous, and often increase player frustration. [citation needed] However, there are some common solutions, such as employed by block wargames, which can simulate fog of war conditions in relatively playable ways.

History

[edit]The first modern mass-market wargame, presented as a board game, was designed by Charles S. Roberts in 1953.[1] The game, Tactics, was published by Roberts as "The Avalon Game Company" in 1954 and broke even, selling around 2,000 copies. These sales convinced Roberts that there was a market for intelligent, thoughtful, games for adults. Four years later, he decided to make a serious effort at a game company. Finding a conflict with another local company, he changed the name of the company to The Avalon Hill Game Company.[5]

Avalon Hill

[edit]The beginning of the commercial board wargaming hobby is generally tied to the name "Avalon Hill"[6] and the publication of Tactics II in 1958, along with Gettysburg, the first board game designed to simulate a historical battle. [citation needed]

Avalon Hill was subject to a number of bad economic forces around 1961, and quickly ran up a large debt.[5] In 1963 Avalon Hill was sold to the Monarch Avalon Printing company to settle the debts. The new owners resolved to let the company continue to do what it had been doing, and while Roberts left, his friend, Tom Shaw, who already worked at the company, took over.[7] The sale turned out to be an advantage, as being owned by a printing company helped insure that Avalon Hill games had access to superior physical components.

Roberts had been considering producing a newsletter for his new company. Under the new management, this became the Avalon Hill General in 1964, a house organ that ran for 32 years.

Avalon Hill had a very conservative publishing schedule, typically about two titles a year, and wargames were only about half their line. [citation needed]

This led to some developments which, in light of the present state of the hobby, now seem almost unfathomable. The best examples of which were the D-Day and Stalingrad cults. Hundreds of wargamers, this writer being one of them, strained, sweated, argued and meditated over those two games, devising strategies, set-ups and variants almost ad infinitum. Both games were simultaneously unhistoric and unbalanced, yet we played them (brother, did we play them!), simply because they were the only simulations widely available on the two 'classic' campaigns of World War II.[8]

Serious competition: SPI and GDW

[edit]By the end of the 1960s, a number of small magazines dedicated to the hobby were springing up, along with new game companies. Many of these were not available in any store, being spread by 'word of mouth' and advertisements in other magazines.

The eventual "break-out" into a larger public was accomplished by the magazine Strategy & Tactics.[9] It was started in 1966, as a typical "hobby zine", and despite some popularity soon threatened to go under. However, Jim Dunnigan bought the ailing magazine, and restructured his own company (then known as Poultron Press) to publish it, creating Simulations Publications, Inc. (SPI). An aggressive advertising campaign, and a new policy of including a new game in every issue, allowed S&T to find a much larger market, and SPI to become a company known to all wargamers as having a line of games that surpassed Avalon Hill's (at least, in numbers—arguments about quality raged). [citation needed]

This caused a tremendous rise in the popularity of wargaming in the early 1970s. [citation needed] The market grew at a fast pace, and if anything the number of wargaming companies grew at an even faster pace. Most of these quietly failed after producing a few products. Two of these new companies would each last for about two decades and became well known in just a few years: Game Designers' Workshop (GDW), and Tactical Studies Rules (TSR).

Started in 1973 by Frank Chadwick, Rich Banner, Marc W. Miller, and Loren Wiseman, GDW's first game, Drang Nach Osten!, immediately garnered attention and led to the Europa series. They quickly followed this with other games, which also got favorable reviews. It has been estimated that GDW published one new product every 22 days for the 22 year life of the company (to be fair, this would include magazines and supplements, not just complete games).[10]

TSR was started in 1973 by Gary Gygax and Don Kaye as a way to publish the miniature rules developed by the Tactical Studies wargaming club (thus, Tactical Studies Rules). While TSR produced several sets of miniature rules, and a few boardgames, it became much better known as the publisher of Dungeons & Dragons in 1974. The first role-playing game, it sparked a new phenomenon that would later grow much bigger than its parent hobby.

Boom: Task Force Games, Steve Jackson, et al.

[edit]The period 1975–1980 can be considered the 'Golden Age of Wargaming',[11] with a large number of new companies publishing an even larger number of games throughout, powered by an explosive rise in the number of people playing wargames. [citation needed] Wargames also diversified in subject, with early science-fiction wargames appearing in 1974, and in size with both microgames and monster games first appearing during the decade.

Designer Steve Jackson produced several celebrated games for Metagaming Concepts and then founded his own company, Steve Jackson Games in 1980, which is still active today (albeit mostly as an RPG company). Task Force Games was founded in 1979 by former staff of JagdPanther and lived into the 1990s, and its most popular game, Star Fleet Battles is still in print. Squad Leader, often cited as the highest selling wargame ever, [citation needed] was published in 1977.

Crash: The death of SPI

[edit]Decline set in at the beginning of the 1980s, most markedly with the acquisition of SPI by TSR in 1982. [citation needed] From 1975 to 1981 SPI reported $2 million in sales—steady dollar volume during a time when inflation was in double digits. At the same time, the attempt to go from a mail-order business to wholesale caused a cash crunch by delaying payments.[12] By 1982 SPI was in financial trouble and eventually secured a loan from TSR to help it meet payroll. TSR soon asked for the money back, and SPI had to agree to be taken over by TSR. As a secured creditor, they had first opportunity at SPI's assets. However, they refused to take over SPI's liabilities. TSR then refused to honor existing subscriptions to SPIs three magazines, which TSR took over, in addition to nearly the entire existing line of SPI's games.[9] Largely as a result of this, Strategy & Tactics circulation shrank from its high mark of 36,000 in 1980, until TSR sold it off to World Wide Wargames (3W) in 1986, where its circulation continued to shrink to a low 10,000 in 1990.[11]

Meanwhile, most of the existing staff left SPI, and negotiated a deal with Avalon Hill. [citation needed] Avalon Hill formed a subsidiary company, Victory Games, staffed by the former SPI employees. Victory Games was allowed to publish pretty much what they wanted, and produced many commercially and critically successful wargames. [citation needed] However, there were no new hires to replace departing personnel, and the company slowly died a death of neglect in the 1990s. [citation needed]

This period is marked by a decrease in the number of wargamers, and lack of new companies with commercial viability while the larger companies experiment with ways to sell more games in a shrinking market. [citation needed]

Malaise

[edit]

While TSR tried to leverage its line of existing SPI property, Milton Bradley started the Gamemaster line of mass-appeal wargames in 1984. With the financial backing of a company much larger than any in the wargame business, the Gamemaster games had excellent production quality, with mounted full-color boards (something that only Avalon Hill could regularly do), and plenty of small plastic miniatures as game pieces. The games were generally simple, by wargaming standards, but very playable and successful. The first game of the line, Axis and Allies, is still in print today, and has spawned a number of spinoff titles.

The wargaming business continued to be poor, new companies continued to be formed. GMT Games, one of the most respected names in wargaming today, [citation needed] got started in 1991.[13]

The popularity of role-playing games, video games, and, finally, collectible card games continued to draw in new players. These attracted the same sort of players that had gravitated to wargames before, [citation needed] which led to a declining, and aging, population in the hobby. The continued marginal sales of wargames took its toll on the older companies. Game Designers' Workshop went out of business in 1996. Task Force Games went bankrupt in 1999.

In 1998, Avalon Hill itself was sold to Hasbro. While it might have been possible for Hasbro to revitalize the company and wargaming with its distribution chain and marketing clout, it was shown that Hasbro had no interest in this with the immediate laying off of the entire AH staff and the closure of its web site.[14] Combined with Wizards of the Coast's acquisition of TSR the year before, and their acquisition by Hasbro the year after, what is sometimes called the "adventure gaming market" was going through a profound shakeup.

Hasbro has kept the Avalon Hill name as a brand, and republished a few of its extensive back catalog of games, as well as released new ones, and moved the remnant of the Gamemaster series (Axis and Allies) from Milton Bradley to Avalon Hill. While A&A is the only wargame offered by the "new" Avalon Hill, several of AH's wargames have been reprinted by other companies, starting with Multi-Man Publishing's license for the rights to Advanced Squad Leader.[15]

Current

[edit]

The Complete Wargames Handbook shows sales of wargames (historical only) peaking in 1980 at 2.2 million, and tapering off to 400,000 in 1991.[16] It also estimates a peak of about a few hundred thousand (again, historical) board wargamers in the U.S. in 1980, with about as many more in the rest of the world; the estimate for 1991 is about 100,000 total.

Another estimate puts the current number of board wargamers in the 15,000 range (this is limited to people purchasing games, which leaves some room for groups with one person who buys the games, or people who stick to older titles—who do exist, but are cold comfort for publishers). During 2006, several publishers reported that sales were up, but this could remain a short-term bump in sales.[17]

Styles

[edit]The subject matter of wargames is broad, and many approaches have been taken towards the goals of simulating wars on a grand or personal scale. Some of the more popular movements constitute established subgenres of their own that most wargamers will recognize.

Hex-and-counter

[edit]The oldest of the subgenres, and the one that still retains "iconic" status for board wargaming as a whole.[citation needed] It got its start with the first board wargame, Tactics (which, ironically, used a square grid; hexes were a slightly later innovation), and is still used in many wargames today.

In its most typical form, a hex-and-counter wargame has a map with a hexagonal grid imposed over it, units are represented with cardboard counters that commonly have a unit type and designation as well as numerical combat and movement factors. Players take turns moving and conducting attacks. Combat is typically resolved with an odds-based combat results table (CRT) using a six-sided die.

Strategy games

[edit]This subgenre started with Risk in 1957 and focuses on entire wars rather than battles, typically using regions or countries as spaces rather than hexes, and often using plastic pieces. These games are often designed to support more than two players. The Gamemaster Series popularized the subgenre further in the 1980s, with Axis & Allies eventually evolving into an entire line of games. Many American-style board games are strategy wargames.

Block game

[edit]

This subgenre was created in the early 1970s, when Gamma Two Games produced the three initial games of this type. It has long been the province of Gamma Two and its successor, Columbia Games, but recently other companies have been putting out games of the same type.

The defining aspect of this type of game is the use of wooden blocks for the units. These are tilted on their side normally, and then put down for combat. Until combat occurs, the opponent can see how many units are where, but not what type and what strength, introducing fog of war aspects. The blocks are also rotated to show different strength values in a step-reduction system.

Card-driven

[edit]The most recent of the major types of board wargame, which was created by the game We the People published by Avalon Hill in 1994. In most aspects it is much like a typical board wargame (on the simpler side of the spectrum), but play is driven by a deck of cards that both players draw from. These cards control activation points, which allow the use of troops, as well as events that represent things outside the normal scope of the game. Newer card driven games have helped reinvigorate the war game genre as well as other differently themed games. Twilight Struggle, a game based on the Cold War, was ranked #1 on the website BoardGameGeek from December 2010 to January 2016. As of September 2018, it's ranked fifth overall but first for wargames.[18]

Combat resolution systems

[edit]Various games have different methods for resolution of combat results, a central core dynamic for any wargame.

Attacker-defender ratio

[edit]The wargame Panzerblitz is a leading game in the genre of tactical wargames, and was an iconic new type of game when published by Avalon Hill in 1970. In this game, each unit has an attack strength and a defense strength. To resolve combat, the attacker's attack rating and the defender's defense rating are calculated into a simple ratio; the result is rounded off in the defender's favor. One dice cube is rolled. The "Combat Results Table" provides the effect based on which number is rolled; the results can range from "no effect" to partial damage, or another role, or complete destruction of the unit being attacked. [19] [20] [21]

This system is used very widely. the specific methods may vary somewhat. some games simply caloculate the odds of a succssful attack, and the dice rol is either a success or a failure, with no table of varying possible results. [22]

Some other games that use this system include:

- The Russian Campaign, published in 1974 by Jedko Games.

Attack and defense values

[edit]In the board game Axis and Allies, each unit has an attack value and a defense value. During a single attack, each attacking unit gets one dice roll and each defending unit gets one dice roll. if a dice result is the same or less than the appropriate value, then that unit succesfully destroys the enemy. it is possible for both units to be destroyed using this system. [23] [24]

Non-randomized results

[edit]Some wargames do not use dice at all. The results of an attack depend upon a preset table of results, based on atrributes of the involved units, terrain, morale, and other factors. Tactics II utilizes this method. [25] On the other hand, in the 1980 book The Complete Book of Wargames, game designer Jon Freeman dismissed the then-22-year-old Tactics II as unplayable, saying, "Aside from its historical importance, this game has no redeeming qualities. [...] Against an even vaguely competent opponent, [the game] can't be won. The [geography] combines to produce an inevitable stalemate directly across the center of the board." Freeman concluded by giving the game an Overall Evaluation of "Poor", saying, "Tactics II is overdue for retirement."[26]

Competing dice rolls

[edit]In the well-known game Risk (game) the attacker rolls up to three dice, and the defender rolls up to two dice. The defender wins the dice roll if their number is equal to or greater than the attacker; the attacker wins if their dice roll is higher than the defen der, thus giving the defender a slight advantage.

When a player loses a dice roll, they must remove one unit. Battle continues until one player has no armies left, thus losing the battle. In Risk, combat is highly abstract, and all units are treated the same.

See also

[edit]- Air wargaming

- Game Manufacturers Association

- International Wargames Federation

- List of board wargames

- List of wargame publishers

- Naval wargaming

- Origins Game Fair

- Simulation game

- Tactical wargame

References

[edit]- ^ a b Dunnigan, James (1997). "Chapter 5 - History of Wargames". The Complete Wargames Handbook (2nd ed.). Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2010-02-14..

- ^ Garthoff, Jon (2018-12-30). "Playability as Realism". Journal of the Philosophy of Games. 1 (1). doi:10.5617/jpg.2705. ISSN 2535-4388.

- ^ Barnes, Michael (2 December 2019). "A Brief History of the "Dudes on a Map" Genre". There Will Be Games. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ a b Niles, Douglas (2007). "Terrible Swift Sword". In Lowder, James (ed.). Hobby Games: The 100 Best. Green Ronin Publishing. pp. 309–311. ISBN 978-1-932442-96-0.

- ^ a b Roberts, Charles. "Charles S. Roberts: In His Own Words". Archived from the original on 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Jason R. Edwards, Saving Families, One Game at a Time Archived 2016-02-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "About Avalon Hill". Hasbro. Archived from the original on March 14, 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ^ Bomba, Tyrone (1974). "Victory Conditions, Neutrality & Capitalist Imperialism". Panzerfaust (65): 33–34, 42.

- ^ a b Costikyan, Greg (1996). "A Farewell to Hexes". Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Far Future Enterprises page on GDW- (Archived July 15, 2006, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ a b Owen, Seth (July 1990). "The History of Wargaming 1975-1990". Strategy & Tactics (136).

- ^ Simonsen, Redmond (1988-08-24). "Why Did SPI Die?". Web-Grognards. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ MacGowan, Rodger. "For what do the letters GMT stand?". GMT Games. Archived from the original on 2008-04-30. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ^ Costikyan, Greg (1998). "A Requiem for the Hill". Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ^ McLaughlin, Mark. "Schilling Pitching for ASL". Wargamer, LLC. Archived from the original on 2008-06-14. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ^ Dunnigan, James (1992). The Complete Wargames Handbook (2nd ed.). New York, N.Y.: Morrow. ISBN 0-688-10368-5. Archived from the original on 2016-04-17. Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ^ Peck, Michael (2006). "The State of Wargaming". Armchair General Magazine. Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ^ "Twilight Struggle". BoardGameGeek. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ Panzerblitz rules of play. pdf of official rules.

- ^ Panzerblitz rulebook, posted at scribd.com website.

- ^ Panzerblitz 2 Rulesbook, at website mmpgamers.com

- ^ The Anvil of Probability: Exploring Combat Results Tables (CRTs) and why they endure in game design Sep 03, 2024,l website skeltoncodemachine.

- ^ Rules for Axis & Allies 50th Anniversary Edition (PDF Rulebook), accessed from Resources directory page at axisandallies.org website. accesed jan 15, 2025.

- ^ How do bombers and planes work in combat?, axisandallies.org website, accesssd January 15, 2025.

- ^ Wargames, nostalgia, and Tactics II: Looking back at one of the first wargames I played, Jun 25, 2024.

- ^ Freeman, Jon (1980). The Complete Book of Wargames. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 205.

External links

[edit]- ConsimWorld.com (Wargame news and discussion site)

- The Wargamer (War and strategy games website, tabletop, miniature, and computer)

- Web-Grognards (Has a listing of most every game and publisher, usually with reviews, extra scenarios, after action reports, etc.)

- Board Game Players Association (Noncommercial group manages the Avaloncon convention and other board wargame events)

- Limey Yank Games (Support of Internet and Play by Electronic Mail systems)