Haitian Declaration of Independence

| Haitian Declaration of Independence | |

|---|---|

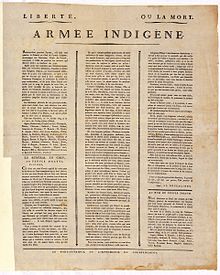

Haitian Declaration of Independence poster, 1804 | |

| Created | 1804 |

| Location | The National Archives, Kew, UK |

The Haitian Declaration of Independence (French: Acte de l'Indépendance de la République d'Haïti) was proclaimed on 1 January 1804 in the port city of Gonaïves by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, marking the end of 13-year long Haitian Revolution. The declaration marked Haiti becoming the first independent nation of Latin America and only the second in the Americas after the United States.[1]

Notably, the Haitian declaration of independence signalled the culmination of the only successful slave revolution in history.[2] Only two copies of the original printed version exist. Both of these were discovered by Julia Gaffield, a Duke University postgraduate student, in the UK National Archives in 2010 and 2011.[2] They are currently held by The National Archives, Kew.

The declaration itself is a three-part document. The longest section, "Le Général en Chef Au Peuple d’Hayti", which is known as the "proclamation," functions as a prologue. It has one signatory, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the senior general and a former slave. Due to Dessalines being illiterate and unable to speak French, his secretary Louis Boisrond-Tonnerre then read out the proclamation, followed by the act of independence, which were both written by the latter.[3] This declaration was later followed by an independence day speech from Dessalines—recited in Haitian Creole—in which he denounced France.[4]

In particular, the declaration demands vengeance against the French White Creoles, who committed atrocities against the African-Haitian population. Dessalines claimed that:

"It is not enough to have expelled the barbarians who have bloodied our land for two centuries; … We must, with one last act of national authority, forever assure the empire of liberty in the country of our birth; we must take any hope of re-enslaving us away from the inhuman government …. In the end we must live independent or die."[5]

These words presaged the 1804 Haiti massacre, which was supervised by Dessalines.

Philippe Girard, a Guadeloupean academic, has noted that the document is multi-layered with references to six different audiences: "the French, Creoles, Anglo-Americans, Latin Americans, mixed-race Haitians, and black Haitians".[6] Moreover, the Haitian declaration was important because it marked the end of a revolution, not the beginning, unlike most revolutionary struggles prior to the mid-twentieth century. Also, the primary motive behind this revolution was not independence, but rather racial equality and emancipation.[1]

Although the declaration repeatedly alluded to "freedom from slavery", there was no mention of "republican rights" within the text. As a result, the new nation under Dessalines came to be known as the l’État d’Haïti (The State of Haiti), rather than the Haitian Republic. Following independence, Dessalines accorded all power to himself as the "head of state", which was made possible by the support of the 17 senior officials that signed the third section of the declaration.[1]

Social context

[edit]The central issue for the Haitian revolution was independence, specifically freedom from their enslavement under France. In its social and political complexity, the Haitian Revolution resembled the simultaneous revolution in France, since the demand of the revolutionaries was secession from the ruling-class of France.[7] Moreover, unlike mainland colonies, Haiti was an easily blockaded Caribbean island with a small population, which made independence a less viable option for them.[1]

For the black slaves, a revolution and the subsequent declaration of independence was a route to emancipation and racial equality, following the re-establishment of slavery in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte. This decision, in particular, catalyzed the revolution among the slaves who had become more content after the abolition of slavery in 1793. This motive resonated with Dessalines, who was a slave himself. Hence, the eventual declaration in 1804 made several mentions of emancipation and freedom from the "cruelties of the French", rather than a de jure claim of independence.

A similar attempt to attain independence was carried out on the night of 21 August 1791, when the slaves of Saint Domingue rose in revolt and plunged the colony into civil war. Within the next ten days, slaves had taken control of the entire Northern Province in an unprecedented slave revolt. However, the Legislative Assembly in France granted rights to the free people of colour, in addition to dispatching 6,000 French soldiers to the island.[8] As a result, a complete secession from France was not undertaken at the time, and only came into effect after slavery was brought back.[1]

For the white Creole revolutionaries, the declaration of independence connoted to political autonomy. Nevertheless, the ensuing 1804 Haiti massacre meant that their aims were not fulfilled, and Haiti became the first black sovereign state in the Americas.[9] The massacre—which took place in the entire territory of Haiti—was carried out from early February 1804 until 22 April 1804. During February and March, Dessalines travelled among the cities of Haiti to assure himself that his orders were carried out. This ensured that the social and political power then rested with the blacks and those of mixed-descent, thereby completely changing the status quo post-independence. As such, emancipation gave Dessalines an avenue to exercise revenge on the former slave-owners, who were systematically persecuted.[10]

Declaring Independence

[edit]On 1 January 1804, Dessalines, the new leader under the dictatorial 1801 constitution, declared Haiti a state in the name of the Haitian people. Dessalines' secretary Boisrond-Tonnerre stated, "For our declaration of independence, we should have the skin of a white man for parchment, his skull for an inkwell, his blood for ink, and a bayonet for a pen!". Incidentally, it is claimed that Boisrond-Tonnerre was chosen to author the declaration by Dessalines due to this statement itself.[3]

Dessalines assigned all power to himself, by taking the title "governor-general for life," which he replaced nine months later with "emperor".[1] His establishing of a de facto dictatorship was, in fact, implied within the declaration text as well:

"Remember that I sacrificed everything to rally to your defense; family, children, fortune, and now I am rich only with your liberty; my name has become a horror to all those who want slavery. Despots and tyrants curse the day that I was born. If ever you refused or grumbled while receiving those laws that the spirit guarding your fate dictates to me for your own good, you would deserve the fate of an ungrateful people."[5]

Additionally, there is no assertion of "republican rights", or any "rights" whatsoever within the declaration. Instead, the idea of independence in this context was restricted to freedom from slavery, not liberalisation.[1] This can be traced from the 1791 slave rebellion to the 1801 constitution by Louverture, who created an authoritarian society that transferred absolute control from the French to Dessalines. The militaristic rule of Dessalines—with the support of 17 of the 37 senior army officers that denounced France[4]—bore similarity to the French Revolution that culminated with the ascent of Napoleon as a dictator in France. Furthermore, even though it was successful, Dessalines opted for a revolution only "in one country". Historians have noted that this was due to Dessalines' desire to establish maintain friendly diplomatic relationships with neighboring European-controlled islands, which were largely opposed to dealing with Haiti due to fears of the effect it would have on their own plantation economies.[11] In three conciliatory paragraphs that contrast with the strident tone of the rest of the document, Dessalines asks his countrymen to:

"Ensure, however, that a missionary spirit does not destroy our work; let us allow our neighbours to breathe in peace; may they live quietly under the laws that they have made for themselves, and let us not, as revolutionary firebrands, declare ourselves the lawgivers of the Caribbean, nor let our glory consist in troubling the peace of the neighbouring islands. Unlike that which we inhabit, theirs has not been drenched in the innocent blood of its inhabitants; they have no vengeance to claim from the authority that protects them."[5]

Despite this, however, the Haitian Revolution and its consequent independence were unlike other revolutions of the time. The general post-independence autocratic tradition in Haiti differentiated it from most other Latin American societies that became republics following a revolution, with the exception of a select few that became monarchies. It was only after the assassination of emperor Dessalines in 1806, that the freed slaves—also signatories of the declaration—went on to establish Haiti's first republic.[1]

The Act of Independence was supposed to be held at the National Archives building in Port-au-Prince, and it was there until the government of Fabre Geffrard sold to a German who wanted to exhibit it in the British Museum. After the 2010 earthquake, in April 2010, a Canadian graduate student at Duke University was studying in London found the only surviving copy of the original printing in The National Archives.[12]

International Response

[edit]After the Declaration of Independence, western powers refused to recognize Haiti as an independent state. The Haitian government responded by leveraging their economic relationships with other countries to persuade them to recognize Haiti’s sovereignty. This tactic, and Haiti’s attempts at reassuring their colonial neighbors, were ultimately unsuccessful. Haiti was denied diplomatic recognition for decades after the Declaration.

Post-Declaration of Independence, Haiti was not recognized by the United States, but U.S. merchants traded freely with Haiti. Haiti used this economic relationship to put pressure on the United States for diplomatic recognition. Haiti refused to enter negotiations or aid in resolving disputes without diplomatic recognition. U.S. merchants put pressure on the government to recognize Haiti as an independent country so that their trade with Haiti was better protected. However, this tactic to gain U.S. diplomatic recognition was unsuccessful, as Haiti was not recognized by the U.S. until 1862.[13]

The Declaration tried to reassure foreign slave-holding states that the Haitian revolutionaries did not mean to threaten their colonies with slave rebellion as well. Instead of wide-spread slave rebellion, Dessalines calls for the revolution to be contained to Haiti. This statement was likely included to protect Haiti from retaliation from nearby colonial powers, such as barriers to trade from the British navy.[14]

Despite the claims in the Declaration, surrounding slave-holding colonial powers saw Haiti as a threat. Haiti was free soil for enslaved people from other nations. The 1816 constitution of Haiti included an article that granted citizenship to anyone of African descent who came to live in Haiti. The free soil policy offered the enslaved people of the Caribbean a means of escape, so long as they could reach Haiti. Many did and gained freedom from this method. When foreign powers, like the British, tried to negotiate for the slaves’ return, they were hindered by their own non-recognition of Haiti.[15]

Even though Haiti identified itself as a Catholic nation, the Vatican did not recognize Haiti as an independent nation in the decades following the Declaration. The Vatican identified Haiti under its colonial name, and sent a bishop under a title used for missionary work, instead one used for interacting with an established Catholic nation. The Vatican’s rejection of Haiti as an independent state further alienated the new nation from the surrounding colonial powers. Also, it placed Haiti outside of the group of so-called “civilized” nations.[16]

Signatories

[edit]- Jean-Jacques Dessalines General-in-chief

- Henri Christophe, division chief

- Alexandre Pétion, division chief

- Nicolas Geffrard, division chief

- Augustin Clerveaux, Major General

- Vernet, Major General 1

- Gabart, Major General 1

- Laurent Bazelais, Brigadier General[17]

- P. Romain, G. Gérin, F. Capois, Jean-Louis François, Férou, Cangé, Magloire Ambroise, JJ Herne, Toussaint Brave, Yayou, generals of brigades;

- Guy Joseph Bonnet, F. Paplier, Morelly, Chevalier, Marion, adjutants-general

- Magny, Roux, heads of brigades;

- Chaperon, B. Goret, Macajoux, Benjamin Noel, Ololoy, Dupuy, Carbonne, Diaquoi elder, Raphaël, Malet, Derenoncourt, officers of the Haitian army

- Pierre Nicolas Mallet alias Mallett Bon Blanc [1]

- Louis Boisrond Tonnerre, secretary

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Geggus, David (2011). Canny, Nicholas; Morgan, Philip (eds.). "The Haitian Revolution in Atlantic Perspective". The Oxford Handbook of the Atlantic World. 1. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199210879.013.0031.

- ^ a b Gaffield, Julia. "Haiti's Declaration of Independence: Digging for Lost Documents in the Archives of the Atlantic World". The Appendix. 2.

- ^ a b Madiou, Thomas. Histoire D'Haïti. Port Au Prince: Imprimerie De JH Courtois, 1847. Print.

- ^ a b Madiou, Thomas. Histoire D'Haïti. Port Au Prince: Imprimerie De JH Courtois, 1847. 3:146

- ^ a b c "Rediscovering Haiti's Declaration of Independence | The Declaration's Text (in Translation)". today.duke.edu. Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- ^ Girard, Phillipe (2005). Paradise Lost: Haiti's Tumultuous Journey from Pearl of the Caribbean to Third World Hotspot. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403968876.

- ^ Akamefula, Tiye, Camille Newsom, Burgey Marcos, and Jong Ho. "Causes of the Haitian Revolution." Haitian Revolution. September 1, 2012. Accessed March 25, 2015. http://haitianrevolutionfblock.weebly.com/causes-of-the-haitian-revolution.html.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Blackpast.com [2], Haitian Revolution 1791–1804

- ^ Taber, Robert D. "." 13, no. 5 (2015): 235–50. doi:10.1111/hic3.12233. (2015). "Navigating Haiti's History: Saint-Domingue and the Haitian Revolution". History Compass. 13 (5): 235–50. doi:10.1111/hic3.12233

- ^ Girard 2011, pp. 321–322.

- ^ David Geggus, "The Influence of the Haitian Revolution on Blacks in Latin America and the Caribbean," in Blacks, Coloureds and National Identity in Nineteenth-Century Latin America, ed. Nancy Naro (London, 2003), 46.13

- ^ Cave, Damien (2010-04-01). "Haiti's Founding Document Found in London". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-06-17.

- ^ Gaffield, Julia. “Outrages on the Laws of Nations: American Merchants and Diplomacy after the Haitian Declaration of Independence.” In The Haitian Declaration of Independence, edited by Julia Gaffield. University of Virginia Press, 2016.

- ^ Geggus, David. “Haiti’s Declaration of Independence.” In The Haitian Declaration of Independence: Creation, Context, and Legacy, edited by Julia Gaffield. University of Virginia Press, 2016.

- ^ Gonzalez, Johnhenry. “Defiant Haiti: Free-Soil Runaways, Ship Seizures and the Politics of Diplomatic Non-Recognition in the Early Nineteenth Century.” Slavery & Abolition 36, no. 1 (2015): 124-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144039X.2014.895508.

- ^ Gaffield, Julia. “The Racialization of International Law after the Haitian Revolution: The Holy See and National Sovereignty.” American Historical Review 125, no. 3 (2020): 841-868. https://doi.org/10.1093ahr/rhz1226.

- ^ Saga Antillaise Tome 1, Frisch, Peter J. ISBN 978-99935-0-333-0

External links

[edit]- Revolutions podcast episode 4.17a, an audio recording of Mike Duncan reading an English translation of the Declaration