Krue Se Mosque

| Krue Se Mosque | |

|---|---|

Masjid Gresik มัสยิดกรือเซะ | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Branch/tradition | Sunni |

| Location | |

| Location | Pattani, Thailand |

| Geographic coordinates | 6°52′23″N 101°18′11″E / 6.87306°N 101.30306°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | mosque |

| Groundbreaking | 16th century |

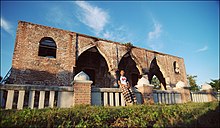

Krue Se Mosque (Malay: Masjid Kerisek; Thai: มัสยิดกรือเซะ, RTGS: Matsayit Kruese) also called Gresik Mosque, Pitu Krue-ban Mosque (Thai: มัสยิดปิตูกรือบัน), Pintu Gerbang Mosque, or Sultan Muzaffar Shah Mosque, is a mosque in Pattani Province, Thailand. Its construction may have begun in the 16th century. The surviving structure is described as having a mixture of Middle Eastern or European architectural styles.[1]

History

[edit]It is unclear when the mosque was first constructed as different dates are given by different sources,[2] although a mosque may have been rebuilt several times at the same location. According to Hikayat Patani, a history of the Patani Kingdom, two mosques were constructed during the reign of Sultan Muzaffar Shah (d. 1564). One of the mosques was built outside the main gate ("Pintu Gerbang") of the citadel beside the town square (padang), likely the location of the present Krue Se Mosque.[3] The construction date has also been proposed to be around 1578–93 during the reign of the Ayutthaya king Naresuan the Great;[4] or in 1722 or 1728–29, but left incomplete due to a power struggle between the Sultan of Patani and his brother;[1] or before 1785.[2] The bricks used for the construction of the mosque are from the latter period of the Ayudhaya era, and construction dates of 1656–1688 have therefore also been suggested.[2] At the base of the mosque are bricks in the style of the Dvaravati period.[5] The bricks, however, may be from somewhere else and older than the mosque itself.[2]

Some believe that the mosque was built by the Chinese pirate Lim Toh Khiam, who established a base in Patani in 1578. According to local lore, Lim married the daughter of the Sultan of Patani, claimed to be Raja Hijau, and converted to Islam.[6] Next to the mosque is a garden as well as the gravestone of Lim Ko Niao, described as the sister of Lim Toh Khiam, who in this tale placed a curse so the dome of the mosque could not be completed.[7][8][9] Lightning was said to have struck the mosque every time an attempt was made to complete the building, although there is no evidence that the building has ever suffered from lightning strikes.[2]

A mosque was known to have been constructed by the early 17th century; Jacob van Neck wrote in a Dutch report in 1603 that the then principal mosque of Patani "was very neatly constructed by Chinese workers from red bricks".[6] A later 17th-century account by Dutch traveler Johan Nieuhof says of the mosque in Patani:

The Mohametan church is a stately edifice of red brickwork, gilt very richly within, and adorned with pillars, curiously wrought with figures. In the midst close to the wall is the pulpit, carv'd and gilt all over, unto which the priests are only permitted to ascend by four large steps.[10]

The mosque may have been left in ruins after Pattani was captured and sacked by the Siamese in 1785. The mosque was said to have been rebuilt in the 19th century by Tuan Sulong who governed Pattani from 1816 to 1832.[11] The mosque became known as Krue Se Mosque (Masjid Kerisik in Malay) after the Ban Krue Se (Kampung Kerisik) area it is located. Kerisik likely originated from gersek meaning "coarse-grained sand".[12] The mosque was designated a historical site by the Department of Fine Arts of Thailand in 1935 and a minor renovation was undertaken two years later. Major restoration works on its structure were conducted in 1957 and 1982.[13][14] Further renovation was completed in 2005.[15]

Krue Se Mosque incident

[edit]On 28 April 2004, during Thaksin Shinawatra's premiership and in a period of insurgency by Islamic nationalists in the southernmost provinces, 32 gunmen took shelter in the mosque, after more than 100 militants carried out attacks on 10 police outposts across Pattani, Yala, and Songkhla Provinces.[16] After a seven-hour stand-off with Thai military personnel, soldiers attacked and killed all 32.[17] The attack contravened orders from the Minister of Defence to end the confrontation peacefully, and has been the subject of an international inquiry, which concluded the military used excessive force.

In 2013, a replica of Phaya Tani, a cannon taken to Bangkok after Pattani was captured by Siam in 1785, was created and placed in front of Krue Se Mosque. However, it was damaged due to bombing by separatists who saw it as 'faked' and wanted the return of the original cannon regarded as the symbol of Pattani.[18][19]

Architecture

[edit]

The mosque is constructed of bricks built on a base with a dimension of 15.1m in width and 29.6m in length. Its height from floor to ceiling is 6.5m. Its pillars are similar to the European style of columns.[5] Its columns with pointed arches, arched doors and rounded-arch windows, have been described as European Gothic, but they are more likely Middle Eastern or Persian. The building itself is incomplete.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "มัสยิดกรือเซะ". Pattani Province. Archived from the original on 29 June 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f Chaiwat Satha-anand. "Kru-ze: A Theatre for Renegotiating Muslim Identity". Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia. 8 (1): 195–218. JSTOR 41035733.

- ^ Bougas, Wayne (1990). "Patani in the Beginning of the XVII Century". Archipel. 39: 113–138. doi:10.3406/arch.1990.2624.

- ^ Alan Teh Leam Seng (1 June 2019). "Mystery of the unfinished mosque". New Straits Times.

- ^ a b "แหล่งโบราณคดีภาคใต้ - มัสยิดกรือเซะ". OpenBase.in.th. 15 January 2009.

- ^ a b Reid, Anthony (30 August 2013). Patrick Jory (ed.). Ghosts of the Past in Southern Thailand: Essays on the History and Historiography of Patani. NUS Press. pp. 12–13, 22–23. ISBN 9789971696351.

- ^ Francis R. Bradley (2008). "Piracy, Smuggling, and Trade in the Rise of Patani, 1490–1600" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 96: 27–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-01-23. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- ^ "แหล่งโบราณคดีภาคใต้ - มัสยิดกรือเซะ". คลังเอกสารสาธารณะ. 19 May 2009.

- ^ "Mystical ties". Bangkok Post. 28 February 2019.

- ^ Sheehan, J. J. (1934). "Seventeenth Century Visitors to the Malay Peninsula". JMBRAS. 12 (2): 94–107. JSTOR 41559513.

- ^ Ibrahim Syukri. "Chapter 3: The Government of Patani in the Period of Decline". History of Patani. from History of the Malay Kingdom of Patani ISBN 0-89680-123-3.

- ^ Perret, Daniel (2022). Daniel Perret; Jorge Santos Alves (eds.). "Patani Through Foreign Eyes: Sixteenth And Seventeenth Centuries". Archipel. Hors-Série n°2 B. The Sultanate of Patani: Sixteenth-Seventeenth Centuries Domestic Issues. doi:10.4000/archipel.2849.

- ^ "All points lead to Pattani". The Nation Thailand. 5 July 2019.

- ^ Apinya Baggelaar Arrunnapaporn (2008). "Heritage Interpretation and Spirit of Place: Conflicts at Krue Se Mosque and Thailand Southern Unrest" (PDF). ICOMOS.

- ^ "บูรณะ" มัสยิดกรือเซะ" เสร็จเรียบร้อย". ประชาไท. 4 February 2005.

- ^ "Shattered by horrific events". The Nation. 29 April 2006. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ "Thai mosque killings criticised". BBC News. 28 July 2004.

- ^ Veera Prateepchaikul (14 June 2013). "Time to return the Phaya Tani cannon". Bangkok Post.

- ^ "Phaya Tani replica cannon bombed". Bangkok Post. 11 June 2013.