Legal tradition

A legal tradition or legal family is a grouping of laws or legal systems based on shared features or historical relationships.[1] Common examples include the common law tradition and civil law tradition. Many other legal traditions have also been recognized. The concepts of legal system, legal tradition, and legal culture are closely related.

The understanding of legal families and traditions has shifted over time. Early and mid-20th-century efforts at classifying legal systems commonly employed a taxonomic metaphor, and assumed that the affiliation of a legal system with a legal family was static and that mixed legal systems were an exceptional case. Under more recent understandings, legal systems are understood to partake of multiple legal traditions.

Definitions

[edit]

The concept of a legal tradition is widely used, with varying definitions, in the disciplines of comparative law and comparative legal history.[2] In comparative law, the theory of legal traditions is strongly associated with the scholarship of H. Patrick Glenn. The concept of a legal tradition may also be used more broadly to understand the laws of a legal system or traditions within a legal system.

In the influential 1969 comparative law work The Civil Law Tradition, John Henry Merryman defined a "legal tradition" as "a set of deeply rooted, historically conditioned attitudes about the nature of law, about the role of law in the society and the polity, about the proper organization and operation of the legal system, and about the way law is or should be made, applied, studied, perfected, and taught."[2]

The concepts of legal tradition, legal culture, and legal system are closely related and are sometimes used interchangeably.[3] At the level of a national legal system, a national legal tradition relates the legal system to the culture of which it is a part.[4]

In contrast, H. Patrick Glenn avoided formulating any single definition of legal tradition "because the (various) definitions are out there" and "one must simply work with them".[2] Glenn did however define "tradition" as a "loose conglomeration of data, organized around a basic theme or themes".[2] The metaphor of a bee swarm has been used to understand the loosely organized nature of a legal tradition.[5]

History

[edit]

The first documented efforts at grouping legal systems date from the early modern period and the first efforts at comparative law. For example, in 1602 William Fulbecke classified the laws of Europe as Anglo-Saxon (common law), continental (civil law), and canon law.[6]

The first systematic taxonomies of legal systems were developed in the late 19th century. In 1880, the French comparatist Ernest Désiré Glasson presented a taxonomy based on the proximity of different legal systems to Roman law: a first group strongly influenced by Roman law, and including Portugal, Italy, and Romania; a second group moderately influenced by Roman law and including England, Russia, and Scandinavia; and a third group with a mixture of Germanic and Roman influences including France and Germany.[7] In 1893 the Brazilian jurist Clóvis Beviláqua adapted this taxonomy by adding Latin American systems as a fourth family, a classification that was followed by a number of subsequent Latin American comparatists.[8] Taking a more global view, in 1884, the Japanese comparatist Hozumi Nobushige divided the world's legal systems into Indian, Chinese, Islamic, Anglo-Saxon, and Roman families.[9]

Breaking with these early ad-hoc classifications, at the 1900 International Conference on Comparative Law in Paris, Gabriel Tarde called for the grouping of legal systems to be put on a taxonomic basis similar to the taxonomies that had been developed in linguistics and biology.[10] Early taxonomies by Adhémar Esmein and Georges Sauser-Hall adopted linguistic and racial bases for classification, but were not widely adopted due to the lack of a demonstrated connection between these bases and the attributes of the legal systems.[9]

In 1923, Henri Lévy-Ullmann developed the first grouping of legal systems based on sources of law: English law (based on custom), civil law (based on written sources), and Islamic law (based on religious revelation).[11] This was the first clear statement of the dichotomy between civil and common law that later became commonplace.[11] By the 1950s a division of legal systems between common law and civil law families had become prevalent.[12]

In 1950, René David presented a division of the world's legal systems into Western, socialist, Islamic, Hindu, and Chinese groups.[13] In 1962, he replaced this with a much more influential division into "Romano-Germanic", common law, and socialist legal families.[13] David emphasized the inevitably arbitrary nature of these classifications.[14]

In 1961, Adolf Schnitzer divided the world's legal systems into five "circles" (Rechtskreise): primitive, ancient, Euro-American, religious, and Afro-Asian.[15] The ancient circle included the legal systems of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, ancient Greece, and ancient Rome; the Euro-American circle included all of the legal systems of modern Europe and the Americas. Schnitzer regarded these five legal groups as corresponding to the five great Kulturkreise of the world.[15]

By the later 20th century the division between civil law and common law traditions was increasingly challenged or abandoned by comparative law scholars, along with taxonomic approaches to legal system classification in general.[16] However, in the same period that taxonomic approaches were being abandoned in comparative law, the legal origins theory became popular among economists.[17]

In the late 20th and 21st century, more dynamic and flexible understandings of legal traditions have taken hold, in which most or all legal systems partake of multiple legal traditions.[18][19]

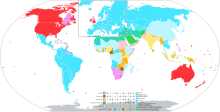

Major legal traditions

[edit]Accounts of the world's legal traditions vary. Glenn's influential but controversial[2] classification divided the laws of the world into six major legal traditions: chthonic (roughly corresponding to customary law and Indigenous law), common law, civil law, Confucian, Hindu, Talmudic, and Islamic.[20] These can be further grouped into four global categories:[21]

- Traditions based on oral tradition (chthonic)

- Traditions based on religious revelation (Talmudic, Islamic)

- Traditions emphasizing duty (Confucian, Hindu)

- Traditions based on state power (common, civil)

In Glenn's analysis, any particular country's laws will typically draw on multiple traditions. Thus for example he analyzes the law of the People's Republic of China as a layering of Confucian and Western traditions.[22]

Further reading

[edit]- Glenn, H. Patrick (2014). Legal Traditions of the World: Sustainable Diversity in Law (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199669837.

- Head, John Warren (2011). Great Legal Traditions: Civil Law, Common Law, and Chinese Law in Historical and Operational Perspective (PDF). Carolina Academic Press. ISBN 9781594609572.

- Merryman, John Henry; Pérez-Perdomo, Rogelio (2018). The Civil Law Tradition: An Introduction to the Legal Systems of Europe and Latin America (4th ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 9781503607552.

References

[edit]- ^ Glenn, H. Patrick (2006). "Comparative Legal Families and Comparative Legal Traditions". In Reimann, Mathias; Zimmermann, Reinhard (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Law. pp. 420–440. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199296064.013.0013. ISBN 9780199296064.

- ^ a b c d e Duve, Thomas (2018). "Legal traditions: A dialogue between comparative law and comparative legal history". Comparative Legal History. 6 (1): 15–33. doi:10.1080/2049677X.2018.1469271.

- ^ Mousourakis, George (2019). Comparative Law and Legal Traditions: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Springer Nature. p. 137. ISBN 9783030282813.

- ^ Mousourakis 2019, p. 133.

- ^ Valcke, Catherine (2021). "Legal Systems as Legal Traditions". In Dedek, Helge (ed.). A Cosmopolitan Jurisprudence: Essays in Memory of H. Patrick Glenn (PDF). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 143. doi:10.1017/9781108894760.008. ISBN 978-1-108-89476-0.

- ^ Mousourakis 2019, p. 143.

- ^ Pargendler, Mariana (2012). "The Rise and Decline of Legal Families". The American Journal of Comparative Law. 60 (4): 1048. JSTOR 41721695.

- ^ Pargendler 2012, p. 1049.

- ^ a b Mousourakis 2019, p. 144.

- ^ Pargendler 2012, p. 1050.

- ^ a b Mousourakis 2019, p. 145.

- ^ Pargendler 2012, p. 1046.

- ^ a b Pargendler 2012, p. 1053.

- ^ Pargendler 2012, p. 1053-54.

- ^ a b Mousourakis 2019, p. 158.

- ^ Pargendler 2012, p. 1044.

- ^ Pargendler 2012, p. 1045.

- ^ Ragone, Sabrina; Smorto, Guido (2023). Comparative Law: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 38. ISBN 9780192645470.

- ^ Glenn 2006, pp. 422–423.

- ^ Ragone & Smorto 2023, p. 38.

- ^ Ragone & Smorto 2023, p. 39.

- ^ Glenn 2014, pp. 349–350.