Marie-Jeanne Lamartinière

Marie-Jeanne Lamartinière (fl. 1802) was a Haitian revolutionary, soldier, and nurse. Described as a Mulatto, she was raised on a plantation in Port-au-Prince. Marie-Jeanne received formal education before marrying Louis Daure Lamartinière, an officer of the Armée Indigène. In 1802, she fought alongside him and his army against French forces in the Battle of Crête-à-Pierrot. Her attire and weaponry were noted, and she was described as courageous. After a bombardment by the French, Marie-Jeanne retreated with Louis and his army, and after his death, she had relationships with two other army officers. Though little is known about Lamartinière, she is popular across Haiti and was printed on a postage stamp and coin.

Biography

[edit]Marie-Jeanne Lamartinière is described as a Mulatto and was born in Port-au-Prince.[1] She was likely born to an enslaved African woman and her white French master, though it is uncertain whether their relationship was unconsensual or one of subsistence. She may have also had Taíno ancestry. Lamartinière was raised on a slave plantation and received formal education from teachers specializing in Haitian Vodou and African culture.[2]

Marie-Jeanne eventually married Louis Daure Lamartinière, an officer of color of the Armée Indigène, a belligerent in the Haitian Revolution. He served as a superior officer during the Battle of Crête-à-Pierrot in March 1802.[3] Reportedly inseparable from him, Marie-Jeanne fought alongside Louis and his army of enslaved men to protect the fort from French forces. Her attire drew comparisons to Mamluk uniforms.[4] Modern sources describe her as cross-dressing in a male uniform[5][6] or wearing a long white dress.[7] Marie-Jeanne also wore a red bonnet, though some of her black hair overflowed. She hung a rifle over her shoulder and attached a scarf and cutlass to her steel belt.[4][8]

Marie-Jeanne crossed the ramparts of the fort to hand out cartidges or load cannons. When the battle intensified or French forces approached, she ran to the frontlines and shot her rifle with "wild enthusiam", as characterized by the historian Thomas Madiou.[4] On the frontlines, Marie-Jeanne is said to have become a manbo possessed by Ogou, a spirit of courage, and when a wounded man on the ground shouted of this spirit, she carried him to shelter. She then nursed him and gave him a rifle.[9] Marie-Jeanne also once urged the other men to hide under a collapsed part of the fort.[4]

After three unsuccessful assaults, the French forces had received 1,500 casualties, and the fort was left defended by 1,200 men. Jean-Jacques Dessalines commanded repairs to the fort and the construction of a redoubt on a nearby hill. Louis headed the redoubt, where Marie-Jeanne remained by his side.[10] On its walls, she shouted motivation to the men.[11] On March 22, the French forces launched a bombardment that killed one hundred men and depleted the fort's resources. Spies for the Armée Indigène then delivered Dessalines's ring to Louis, a secret code ordering them to evacuate. Nearly half of the remaining army snuck out at night.[12] Marie-Jeanne followed Louis, who was traveling to Cahos, and nursed him when he fell sick in a cane field.[4]

Louis was killed in an ambush in November 1802.[13] He was fond of Marie-Jeanne and attributed beauty, courage, and youth to her.[4] Marie-Jeanne then reportedly became the mistress of Dessalines, who proclaimed Haiti's independence in 1804.[2][4] Later, she began a relationship with an officer she had fought alongside with the surname Larose.[4]

Legacy

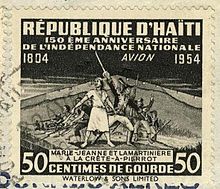

[edit]Lamartinière is depicted in Charles Moravia's 1908 play La Crête-à-Pierrot.[14] She was printed on a 100-gourde coin and a 1954 postage stamp.[15] For the 1967 revision of his play Toussaint Louverture: The Story of the Only Successful Slave Revolt in History, C. L. R. James loosely based the character Marie-Jeanne around Lamartinière. James depicted her in battle, and otherwise rewrote her as an enslaved woman whose light skin and mastery of European culture grant her higher status and a servant. Toward the end, Marie-Jeanne reluctantly marries Dessalines. Lamartinière is celebrated in works by the authors Edwidge Danticat, Madison Smartt Bell, and Patricia Brintle.[16] A painting by the Haitian artist François Cauvin that depicts Lamartinière will display in a Fitzwilliam Museum exhibition in 2025.[6]

Lamartinière is one of the few named women in the Haitian Revolution.[17] Still, little is known about her, especially her early life, and in contrast to modern characterizations of the Battle of Crête-à-Pierrot, the historian Jasmine Claude-Narcisse believes she would have wished to blend in and remain anonymous.[4] The sociologist Madeleine Sylvain-Bouchereau considers Lamartinière a Haitian symbol of the female soldier,[18] and the historian Dantès Bellegarde compared her to Joan of France, Joan of Arc, and Jeanne Hachette in bravery.[1] She is popularly referred to as "Haiti's Joan of Arc" and is well known across the country.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Bellegarde 1950, p. 223.

- ^ a b Accilien, Adams & Méléance 2006, p. 86.

- ^ Trouillot 2021, pp. 147, 149.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Claude-Narcisse, Jasmine; Narcisse, Pierre-Richard (1997). "Marie-Jeanne". haiticulture.ch (in French). Archived from the original on April 23, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Albanese 2024b, p. 86.

- ^ a b Eleode, Emi (August 29, 2024). "'In Some Cases, It Was the Women Who Were Fiercest in the Fight': The Female Freedom Fighters of the Haitian Revolution". BBC News. Archived from the original on August 29, 2024. Retrieved December 1, 2024.

- ^ Accilien, Adams & Méléance 2006, p. 85.

- ^ Accilien, Adams & Méléance 2006, pp. 85, 87.

- ^ Accilien, Adams & Méléance 2006, p. 87.

- ^ Girard 2011, p. 131.

- ^ Accilien, Adams & Méléance 2006, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Girard 2011, p. 132.

- ^ Trouillot 2021, p. 147.

- ^ "En marge des livres: La Crête-à-Pierrot". Le Nouvelliste (in French). June 3, 1908. pp. 1–2 – via Digital Library of the Caribbean.

- ^ Albanese 2024b, p. 91.

- ^ Albanese 2024a, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Gautier 1985, p. 221.

- ^ Sylvain-Bouchereau 1957, p. 69.

- ^ Bellegarde-Smith 2004, p. 41; Albanese 2024b, p. 85.

Bibliography

[edit]- Accilien, Cécile; Adams, Jessica; Méléance, Elmide, eds. (2006). Revolutionary Freedoms: A History of Survival, Strength and Imagination in Haiti. Caribbean Studies Press. ISBN 978-1-58432-293-1.

- Albanese, Mary Grace (July 2024a). "'A New Rhythm Starts Immediately': Women's Spiritual Literacy in The Black Jacobins". Small Axe. 28 (2): 17–33. doi:10.1215/07990537-11382426. S2CID 273133006.

- Albanese, Mary Grace (2024b). Black Women and Energies of Resistance in Nineteenth-Century Haitian and American Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-00-931426-8.

- Bellegarde, Dantès (1950). Ecrivains haïtiens: Notices biographiques et pages choisies (in French). Éditions Henri Deschamps. OCLC 2616899.

- Bellegarde-Smith, Patrick (2004). Haiti: The Breached Citadel (Revised and updated ed.). Canadian Scholars' Press. ISBN 978-1-55130-268-3.

- Gautier, Arlette (1985). Les sœurs de solitude: La condition féminine dans l'esclavage aux Antilles du XVIIe au XIXe siècle (in French). Éditions Caribéennes. ISBN 978-2-903033-64-4.

- Girard, Philippe R. (2011). The Slaves Who Defeated Napoléon: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian War of Independence, 1801–1804. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-1732-4.

- Sylvain-Bouchereau, Madeleine (1957). Haïti et ses femmes: Une étude d'évolution culturelle (in French). Les Presses Libres. OCLC 2221385.

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph (2021). Past, Mariana; Hebblethwaite, Benjamin (eds.). Stirring the Pot of Haitian History. Translated by Past and Hebblethwaite. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-80085-967-8.