Mumbiram

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Artist Mumbiram | |

|---|---|

Leader of Rasa Renaissance Movement of Aesthetics | |

| Known for |

|

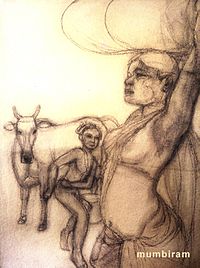

Mumbiram is an Indian painter and author from India known for his leadership of the Rasa Renaissance art movement in India. He is best known for his renderings, in charcoal and color media, of the folk people of India in real-life situations. As a contemporary classical painter, Mumbiram introduced an indigenous art movement and created the Manifesto of Personalism. His concept of personalism in art has proliferated into the Rasa Renaissance movement that is based on the classical rasa theory of Sanskrit literature. It is a theory of aesthetics that evaluates art or literature by the emotions it elicits. Mumbiram is also known for his prema vivarta work of euphemisms, Deluges of Ecstasy, composed during his 12 years in the United States.

Early life

[edit]Mumbiram was born in the busy Mandai vegetable market place of downtown Pune, son of the lawyer and public figure Ramdas Paranjpe. His mother Anjani was the daughter of watercolor artist S. H. Godbole, who was secretary of the Bombay Art Society in the 1930s. Anjani was also the granddaughter of Shri Vartak, the first Indian Chief Engineer of the colonial Bombay Presidency. Mumbiram's father was a nephew of a great spiritual master Shri Ramdasanudas of Wardha, and of R. P. Paranjpye, the first Indian to top the Mathematical Tripos exam at Cambridge.

Mumbiram was a prodigious child artist and won prizes in children's art competitions. As a teenager he was attracted to math and science, and was later at the top of his class when he received his bachelor's degree in Telecommunication Engineering in 1967. Mumbiram attended the University of California, where he got his M.S. in Mathematical Systems in 1968 and a Ph.D. in 1973 for a dissertation in Mathematical Economics.

Birth of personalism and Rasa Renaissance

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (March 2017) |

Mumbiram consistently maintained a philosophical perspective throughout his academic career. He had come to the conclusion that it was aesthetic choices that ruled the destinies of individuals and societies. He himself was always passionately attracted to the beauty of men and women, of body and of spirit. Mumbiram spent six more years in America as an itinerant philosopher and artist. He was already drawing and painting soon after he arrived in Berkeley. It was an intense déjà vu experience with art, his first love in life, although he did not respect contemporary American Art. He visited museums and galleries of contemporary art but found them materialistic. He delved deeply into reading a wide variety of Sanskrit classics and became especially fond of the Bhagavad Gita and the Shrimad Bhagavatam. Krishna, the ultimate hero, is described as Rasaraj (master of all rasas) in esoteric treatises of aesthetic appreciation. According to Mumbiram, everybody is hankering after rasas. Art, music, literature, as well as personalities that arouse rasas, are all eternally dear to people. That is the ultimate aesthetic. Mumbiram finds it unfortunate that contemporary art is floundering aimlessly without any theory of aesthetic criticism whatsoever. He envisions Rasa Renaissance as an inevitability.

The paintings Chitalyanchi Soon and Marathi Poets are examples of Mumbiram's early Personalism. They appeared in the article in Raviwar Sakal, 17 March 1985, "In Search of Art that Transcends Culture".[1]

Itinerant artist in America: Prema Vivarta

[edit]Mumbiram travelled much in America for six more years. The year he spent on Capitol Hill in Seattle, his year in Potomac, Maryland and his two years in Cambridge-Boston in Massachusetts are the most significant periods. He had developed a hands-on approach to painting. Charcoal and ink-and-brush were his forte. Much of his work of these years remains with unknown individuals.

The two works Alice Cooper Washing Mumbiram's Hair and Red-Haired Amateur Palmist Girl Reading Krishna's Fortune near Govardhan, seen below, are representative of his work in this period. His poetic work “Prema Vivarta” or “Deluges of Ecstasy” was composed during this period. In this work the "prema vivarta" mood is revealed as the art of reconciling the mundane and the transcendental on the path to self-realization. This original work is republished by Distant Drummer of Germany along with four translations Mumbiram made of four great Sanskrit classics. All five of these literary works make the ensemble “High Five of Love”. They are lavishly illustrated with Mumbiram's own masterpieces of Art that were independently made but were inspired by the same ideals.[2]

Dramatic return to India

[edit]After 12 years in America, Mumbiram decided to return to India for purely aesthetic reasons.[3] To avoid the temptation of returning to America soon after, he asked the immigration department to voluntarily deport him to India. An incredulous immigration department refused to comply with his request. When Mumbiram approached the Washington Post, the young journalist Christopher Dickey did an interview with him which appeared on the front page of the daily the next morning, with the banner headline, "Cruel Penance for a Brahmin!".[4] Mumbiram had stated that he wanted to return after 12 years of penance (in Sanskrit: tapa) in the jungle, that is America, in the manner of stages of antiquity. Dickey's article embarrassed the immigration department as well as the Indian Embassy. After enjoying the unexpected limelight for two weeks, Mumbiram returned to the immigration department who promptly locked him up in a DC jail. The chargé d'affaires at the Indian Embassy confiscated his passport. At the hearing of the immigration court, Mumbiram was offered a green card citing an executive order of President Jimmy Carter. Mumbiram promptly refused it and was on his way to India under escort. The Times of India had reported this curious case in a sympathetic column in the current affairs section, which began as, "The Law is an ass they say...".[5] Mumbiram had ‘cocked a snook’ at the American Immigration Department and arrived in India to the applause of his fellow men. Within a month after Indira Gandhi returned to power, Mumbiram was issued a new passport with his artist's nom de plume included as his first name on it. Regardless, family and friends treated him as a pariah. In their eyes he ranged from a burnt-out academic to a wayward genius. Mumbiram's ailing old father was one exception. Just to please him, Mumbiram accepted an offer from Pune's Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics to be a postdoctoral research fellow for one year.

Even during this time, Mumbiram found true friendship with the slum-dwelling rag-pickers of Pune, the bird-catching Phas epardis, Warli tribals near Dahanu, and hill-dwelling Thakars of Raigad district. The painting Drupada is coming out of the river with Mumbiram is an outcome of Mumbiram's friendship with Drupada of the Phasephardi tribe. These were to be his natural muses for the next 20 years of his life as a classical painter of Rasa Renaissance.

Legendary atelier in Pune’s Mandai Market (1980-2005)

[edit]The rented house in downtown Mandai market in Pune where Mumbiram was born now lay empty and deserted. Mumbiram made his studio in that dilapidated house with a leaky roof. In that place the next chapter of the Mumbiram saga unfolded with great élan. Soon Mumbiram's atelier saw a steady stream of the folk people of the downtrodden lowest castes and tribes on the one hand and admirers from far corners of the world on the other. Mumbiram's charcoal renderings that show proud beautiful people of India in familiar universal situations were overwhelming favourites with art lovers. They were bought because they were beautiful and full of rasa, not because they were promoted by any galleries or any institutions. The joy of the amateur buyers increased manifold when they came to realize that Mumbiram's muses that appeared in these renderings were from the lowest rungs of the Indian society, the neglected beauties of India. Kusum, Sakhrabai, Drupada, Sonabai are the names that come to mind and are seen in many works. Artlovers could even meet some of them during their visit. Some saw it as the Pygmalion story. The lumpen, ponderous, swarthy creatures who are ignored or pitied on the street appear in Mumbiram's renderings as proud elegant muses of high art. They were destined to adorn walls of well-endowed lovely homes. Some saw it as the Robin Hood story where the artist took from the "haves" and gave it to the "have-nots". It was legendary; a story line fit for great novels and feature films. One gets a glimpse of that in the short documentary, Labyrinth of a Renaissance made by Nadine Grenz.

The charcoal renderings, seen below, Not by bread alone - Kusum making chapattis[2] and Kusum brings her Mother Sakhrabai to visit the Artist[6] are just two of the many masterpieces of this period.

"Forest Women Visit Krishna and the Gopis": A Legendary Painting (1985)

[edit]A verse from the Shrimad Bhagavatam describes how the Pulindya forest women approached the adolescent Krishna surrounded by the Gopis, his cowherd paramours, on the bank of the Yamuna. This verse and this painting appear prominently in Five Songs of Rasa, Mumbiram's English translation of the Sanskrit verses.[7] That vision of the all-attractive Personality of Krishna aroused amorous passions in the Pulindya forest women. The forest women could not get close to Krishna but watched the gopis gingerly placing Krishna's delicate feet on their kumkum-smeared breasts. Krishna's feet got smeared by that red kumkum powder. When Krishna later walked away treading upon the grass, the grass got tainted with some of that kumkum powder from Krishna's feet. The forest women had to satisfy their amorous desires by smearing their faces and bodies with the kumkum-smeared grass Krishna trod upon. The verse had fascinated Mumbiram ever since he first read the Shrimad Bhagavatam years ago in America. Mumbiram made this oil painting on that theme circa 1985. In Mumbiram's painting the gopis surrounding the central figure of Krishna are clearly Bollywood heroines of the 1980s. The Pulindya forest women are all anonymous international beauties of different colours and creeds that are either trying to attract Krishna's attention or swooning. The painting is full of amazing details for the discerning eye. The adolescent Krishna jealously guarded by the gopis is adorned not with gold-studded jewellery but by a garland strung with forest flowers, feathers and leaves such as the forest women would adorn themselves with. The painting is unique for its subject matter as well as artistic virtuosity, treatment and perspective. It is loaded with theological and social nuances. It was the central attraction of Mumbiram's Mandai Studio for over a decade. It changed hands several times before being acquired by an executive of Mercedes Motor Company and taken to Stuttgart in Germany.

-

Rasa Renaissance Masterpiece "Forest Women visit Krishna and the Gopis" Oil on canvas, by Mumbiram, 1985

Visit to Japan: The Gokula painting

[edit]Mumbiram's search for Classics of Sanskrit Literature brought him to Krishna's Vrindavan in the summer of 1987. There he met Sachiko Konno, a student from the Tokyo School of Design who was attracted to Vrindavan in search of an aesthetic ideal. Sachiko was now known by her spiritual name Gokula. Their friendship brought Mumbiram to Japan a few months later. Mumbiram made several oil paintings on canvas during his stay there for a few months. These soulful renderings show a sari-clad young Japanese woman, who is passionately in love with India. Gokula herself is said to have modeled for these and the setting is of Vrindavan in India even though they are made in Japan. These are important landmark paintings of confluence of two cultures.[8]

Literary flagships of Rasa Renaissance: High Five of Love, Mumbiram’s Rasa art juxtaposed with Rasa classics of literature (1995-2005)

[edit]Before that landmark house was torn down by developers in 2005, Mumbiram had completed another ambitious project that he had undertaken after his visit to Vrindavan in 1987. He has rendered four great Rasa Classics in graceful English and contemporary idiom. Vyasa’s "Rasa Panchadhyayi", Jayadeva’s "Gita Govinda" and Vishvanath Chakravarty’s "Prema Samput", appear as "Five Songs of Rasa",[7] "Conjugal Fountainhead"[9] and "Jewel-Box of Highest Secrets of True Love"[10] respectively. A juicy folk version in Vraja Bhasha (dialect of Hindi spoken in the rural area where Krishna appeared 5000 years ago.) of Rupa Gosvami’s "LalitMadhava" is rendered as "Vrindavan Diaries".[11] As English renderings of great eastern classics these are in the same league as Fitzgerald’s Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Richard Francis Burton's "Arabian Nights" or Edwin Arnold’s "Light of Asia". The fifth is Mumbiram's original work "Deluges of Ecstasy"[2] in the lofty Prema Vivarta mood of Love in Separation that he had composed in America. These are published as a five volume ensemble "High Five of Love" by Distant Drummer Publishing of Germany. As literary classics illustrated by the author himself they are reminiscent of works of William Blake and Khalil Gibran.

Involvement with rag-pickers and tribals in the Prema Vivarta mood

[edit]According to Vaishnavism theology Krishna is Rasaraj, the Supreme source of all rasas and depictions of incidents in Krishna's biography are most attractive subjects for Rasa Art.[12] In the ‘prema vivarta’ mood of attachment to Krishna, everything in the phenomenal world appears to the lover of Krishna as a déjà vu of something related to Krishna.[13] Many Rasa masterpieces by Mumbiram are made in the prema vivarta mood. The theme of these renderings is from adolescent Krishna's celebrated activities yet it is enacted by forest tribals and urban rag-pickers. Ashok Gopal quotes Mumbiram: "My raven-dark rambunctious, roaming, rag-picking girlfriends remind me of Krishna and his boys in the forests of Vrindavan."[14] The remote hills of India are inhabited by tribals that subsist on wild grains, fruit, berries, herbs, honey as well as fodder and firewood that is gathered from the forest. At the end of the day men and women come home with heavy loads much to the happiness of those waiting for them all day. The scriptures describe how eagerly the gopis, the cowherd damsels, used to wait for the adolescent Krishna and his friends to return from the forest with the cows.[15]

The charcoal renderings: "Encounter on the Way back from the Forest" and "I let him persuade me" shown below are examples of this theme. Mumbiram thinks it is unfortunate that the civilized world of city people misses out on the very beautiful and touching human side of the lives of tribals that is close to nature. Their life is close to the life of adolescent Krishna that is considered to be the ultimate object of meditation by the revered scriptures of India.[15] These renderings are examples of how enlightenment and aesthetic are intimately intertwined in the Rasa masterpieces of Mumbiram. Sudhir Sonalkar's article "Banishing tourist-type Visions" notices this unique aspect of Mumbiram's art.[16]

-

"I let him persuade me" by Mumbiram, Charcoal, 1986, Pune

-

"Encounter on the Way back from the Forest", by Mumbiram, Charcoal, 1985, Pune

References

[edit]- ^ Mumbiram (17 March 1985). "In Search of Art that Transcends Culture". Raviwar Sakal. Sakal Papers Pvt.Ltd, Pune.

- ^ a b c Mumbiram (6 April 2011). Deluges of Ecstasy. Distant Drummer Publications. ISBN 978-3-943040-04-3.

- ^ "Mumbiram in America". Mumbiram. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ Dickey, Christopher (18 September 1979). "Cruel Penance for a Brahmin". Washington Post.

- ^ "The law is an ass they say". Times of India. 5 October 1979.

- ^ Mumbiram, Artist (26 January 2006). Book Readers - Love on the Gutenberg Galaxy. Distant Drummer. ISBN 978-3-943040-12-8.

- ^ a b Mumbiram, Artist (6 April 2011). Five Songs of Rasa. Distant Drummer. ISBN 978-3-943040-00-5.

- ^ Mumbiram, Artist (5 October 2007). The Gokura Auction - New Era of Japan-India Relations. Distant Drummer. ISBN 978-3-943040-11-1.

- ^ Mumbiram, Artist (6 April 2011). Conjugal Fountainhead. Distant Drummer. ISBN 978-3-943040-01-2.

- ^ Mumbiram, Artist (6 April 2011). Jewelbox of Highest Secrets of True Love. Distant Drummer. ISBN 978-3-943040-02-9.

- ^ Mumbiram, Artist (6 April 2011). Vrindavan Diaries. Distant Drummer. ISBN 978-3-943040-03-6.

- ^ Goswami, Rupa (1932). Ujjwalanilamani. Bombay: Nirnaya Sagar Press.

- ^ Goswami, Krishnadas Kaviraj. Shri Chaitanya Charitamritam. Vrindavan: Harinam Press.

- ^ Gopal, Ashok (24 July 1988). "Waiting in the Wings". Sunday Maharashtra Herald.

- ^ a b Vyasadev, Shri. Shrimad Bhagavatam. Gorakhpur: Gita Press.

- ^ Sonalkar, Sudhir (11 December 1988). "Banishing tourist-type visions". The Sunday Observer, Mumbai.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- www.distantdrummer.org (Distant Drummer Publications)

- The Washington Post, 18 September 1979. "Cruel Penance for a Brahmin" (Front page interview with Mumbiram by Christopher Dickey in which Mumbiram calls America a jungle where he did his 12 year of austerities and penances)

- The Washington Post, 12 October 1979, Interview from Washington D. C. Jail by Christopher Dickey after Mumbiram succeeded in getting deported purely for aesthetic reasons.

- Times of India, October 1979, Item in Current Topics that begins, "The Law is an ass they say". (Mumbiram befuddles the Immigration Barriers)

- Raviwar Sakal: 17 March, 85 "In Search of Art that Transcends Culture"

- Raviwar Sakal: 16 June 1985 "Practice of Personalist Art" (First person accounts by Mumbiram)

- Mumbiram's 1979 poster "ALIEN", this epitomizes young Mumbiram's pursuit of the Romantic Ideal

- Maharashtra Herald, 23 June 1988. “Waiting in the Wings”, an article by Journalist and author Ashok Gopal shows it is impossible for the casual eye to know the brilliant details of Mumbiram's life

- Poona Digest 1989, "Who is Afraid of Friedrich Nietzsche?", article by Mumbiram brings out the inner workings of a creative mind

- Sunday Observer 1989, "Banishing Tourist Type Visions”" Journalist Sudhir Sonalkar's article gives a cursory glimpse about the artist living in the vegetable market place.