Harlem Renaissance

| Part of the Roaring Twenties | |

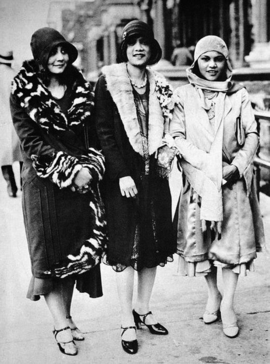

Three African-American women in Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance in 1925 | |

| Date | 1918–mid-1930s |

|---|---|

| Location | Harlem, New York City, United States and influences from Paris, France |

| Also known as | New Negro Movement |

| Participants | Various artists and social critics |

| Outcome | Mainstream recognition of cultural developments and idea of New Negro |

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African-American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s.[1] At the time, it was known as the "New Negro Movement", named after The New Negro, a 1925 anthology edited by Alain Locke. The movement also included the new African-American cultural expressions across the urban areas in the Northeast and Midwest United States affected by a renewed militancy in the general struggle for civil rights, combined with the Great Migration of African-American workers fleeing the racist conditions of the Jim Crow Deep South,[2] as Harlem was the final destination of the largest number of those who migrated north.

Though it was centered in the Harlem neighborhood, many francophone black writers from African and Caribbean colonies who lived in Paris, France, were also influenced by the movement.[3][4][5][6][7] Many of its ideas lived on much longer. The zenith of this "flowering of Negro literature", as James Weldon Johnson preferred to call the Harlem Renaissance, took place between 1924—when Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life hosted a party for black writers where many white publishers were in attendance—and 1929, the year of the stock-market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression. The Harlem Renaissance is considered to have been a rebirth of the African-American arts.[8]

Background

Until the end of the Civil War, the majority of African Americans had been enslaved and lived in the South. During the Reconstruction Era, the emancipated African Americans began to strive for civic participation, political equality, and economic and cultural self-determination. Soon after the end of the Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 gave rise to speeches by African-American congressmen addressing this bill.[9] By 1875, sixteen African Americans had been elected and served in Congress and gave numerous speeches with their newfound civil empowerment.[10]

The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 was followed by the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, part of Reconstruction legislation by Republicans. During the mid-to-late 1870s, racist whites organized in the Democratic Party launched a murderous campaign of racist terrorism to regain political power throughout the South. From 1890 to 1908, they proceeded to pass legislation that disenfranchised most African Americans and many poor whites, trapping them without representation. They established white supremacist regimes of Jim Crow segregation in the South and one-party block voting behind Southern Democrats.

Democratic Party politicians (many having been former slaveowners and political and military leaders of the Confederacy) conspired to deny African Americans their exercise of civil and political rights by terrorizing black communities with lynch mobs and other forms of vigilante violence[12] as well as by instituting a convict labor system that forced many thousands of African Americans back into unpaid labor in mines, plantations and on public works projects such as roads and levees. Convict laborers were typically subject to brutal forms of corporal punishment, overwork and disease from unsanitary conditions. Death rates were extraordinarily high.[13] While a small number of African Americans were able to acquire land shortly after the Civil War, most were exploited as sharecroppers.[14] Whether sharecropping or on their own acreage, most of the black population was closely financially dependent on agriculture. This added another impetus for the Migration: the arrival of the boll weevil. The beetle eventually came to waste 8% of the country's cotton yield annually and thus disproportionately impacted this part of America's citizenry.[15] As life in the South became increasingly difficult, African Americans began to migrate north in great numbers.

Most of the future leading lights of what was to become known as the "Harlem Renaissance" movement arose from a generation that had memories of the gains and losses of Reconstruction after the Civil War. Sometimes their parents, grandparents – or they themselves – had been slaves. Their ancestors had sometimes benefited by paternal investment in cultural capital, including better-than-average education.

Many in the Harlem Renaissance were part of the early 20th century Great Migration out of the South into the African-American neighborhoods of the Northeast and Midwest. African Americans sought a better standard of living and relief from the institutionalized racism in the South. Others were people of African descent from racially stratified communities in the Caribbean who came to the United States hoping for a better life. Uniting most of them was their convergence in Harlem.

Development

During the early portion of the 20th century, Harlem was the destination for migrants from around the country, attracting both people from the South seeking work and an educated class who made the area a center of culture, as well as a growing "Negro" middle class. These people were looking for a fresh start in life and this was a good place to go. The district had originally been developed in the 19th century as an exclusive suburb for the white middle and upper middle classes; its affluent beginnings led to the development of stately houses, grand avenues, and world-class amenities such as the Polo Grounds and the Harlem Opera House. During the enormous influx of European immigrants in the late 19th century, the once exclusive district was abandoned by the white middle class, who moved farther north.

Harlem became an African-American neighborhood in the early 1900s. In 1910, a large block along 135th Street and Fifth Avenue was bought by various African-American realtors and a church group.[16] Many more African Americans arrived during the First World War. Due to the war, the migration of laborers from Europe virtually ceased, while the war effort resulted in a massive demand for unskilled industrial labor. The Great Migration brought hundreds of thousands of African Americans to cities such as Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, Washington, D.C., and New York.

Despite the increasing popularity of Negro culture, virulent white racism, often by more recent ethnic immigrants, continued to affect African-American communities, even in the North.[17] After the end of World War I, many African-American soldiers—who fought in segregated units such as the Harlem Hellfighters—came home to a nation whose citizens often did not respect their accomplishments.[18] Race riots and other civil uprisings occurred throughout the United States during the Red Summer of 1919, reflecting economic competition over jobs and housing in many cities, as well as tensions over social territories.

Mainstream recognition of Harlem culture

The first stage of the Harlem Renaissance started in the late 1910s. In 1917, the premiere of Granny Maumee, The Rider of Dreams, and Simon the Cyrenian: Plays for a Negro Theater took place. These plays, written by white playwright Ridgely Torrence, featured African-American actors conveying complex human emotions and yearnings. They rejected the stereotypes of the blackface and minstrel show traditions. In 1917, James Weldon Johnson called the premieres of these plays "the most important single event in the entire history of the Negro in the American Theater".[19]

Another landmark came in 1919, when the communist poet Claude McKay published his militant sonnet "If We Must Die", which introduced a dramatically political dimension to the themes of African cultural inheritance and modern urban experience featured in his 1917 poems "Invocation" and "Harlem Dancer". Published under the pseudonym Eli Edwards, these were his first appearance in print in the United States after immigrating from Jamaica.[20] Although "If We Must Die" never alluded to race, African-American readers heard its note of defiance in the face of racism and the nationwide race riots and lynchings then taking place. By the end of the First World War, the fiction of James Weldon Johnson and the poetry of Claude McKay were describing the reality of contemporary African-American life in America.

The Harlem Renaissance grew out of the changes that had taken place in the African-American community since the abolition of slavery, as the expansion of communities in the North. These accelerated as a consequence of World War I and the great social and cultural changes in the early 20th-century United States. Industrialization attracted people from rural areas to cities and gave rise to a new mass culture. Contributing factors leading to the Harlem Renaissance were the Great Migration of African Americans to Northern cities, which concentrated ambitious people in places where they could encourage each other, and the First World War, which had created new industrial work opportunities for tens of thousands of people. Factors leading to the decline of this era include the Great Depression.

Literature

In 1917, Hubert Harrison, "The Father of Harlem Radicalism", founded the Liberty League and The Voice, the first organization and the first newspaper, respectively, of the "New Negro Movement". Harrison's organization and newspaper were political but also emphasized the arts (his newspaper had "Poetry for the People" and book review sections). In 1927, in the Pittsburgh Courier, Harrison challenged the notion of the Renaissance. He argued that the "Negro Literary Renaissance" notion overlooked "the stream of literary and artistic products which had flowed uninterruptedly from Negro writers from 1850 to the present," and said the so-called "Renaissance" was largely a white invention.[21][22] Alternatively, a writer like the Chicago-based author, Fenton Johnson, who began publishing in the early 1900s, is called a "forerunner" of the Harlem Renaissance,[23][24] "one of the first negro revolutionary poets".[25]

Nevertheless, with the Harlem Renaissance came a sense of acceptance for African-American writers; as Langston Hughes put it, with Harlem came the courage "to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame".[26] Alain Locke's anthology The New Negro was considered the cornerstone of this cultural revolution.[27] The anthology featured several African-American writers and poets, from the well-known, such as Zora Neale Hurston and communists Langston Hughes and Claude McKay, to the lesser known, like the poet Anne Spencer.[28]

Many poets of the Harlem Renaissance were inspired to tie threads of African-American culture into their poems; as a result, jazz poetry was heavily developed during this time. "The Weary Blues" was a notable jazz poem written by Langston Hughes.[29] Through their works of literature, black authors were able to give a voice to the African-American identity, and strived for a community of support and acceptance.

Religion

Christianity played a major role in the Harlem Renaissance. Many of the writers and social critics discussed the role of Christianity in African-American lives. For example, a famous poem by Langston Hughes, "Madam and the Minister", reflects the temperature and mood towards religion in the Harlem Renaissance.[30] The cover story for The Crisis magazine's publication in May 1936 explains how important Christianity was regarding the proposed union of the three largest Methodist churches of 1936. This article shows the controversial question of unification for these churches.[31] The article "The Catholic Church and the Negro Priest", also published in The Crisis, January 1920, demonstrates the obstacles that African-American priests faced in the Catholic Church. The article confronts what it saw as policies based on race that excluded African Americans from higher positions in the Church.[32]

Discourse

Various forms of religious worship existed during this time of African-American intellectual reawakening.

Although there were racist attitudes within the current Abrahamic religious arenas, many African Americans continued to push towards the practice of a more inclusive doctrine. For example, George Joseph MacWilliam presents various experiences of rejection on the basis of his color and race during his pursuit towards priesthood, yet he shares his frustration in attempts to incite action on the part of The Crisis magazine community.[32]

There were other forms of spiritualism practiced among African Americans during the Harlem Renaissance. Some of these religions and philosophies were inherited from African ancestry. For example, the religion of Islam was present in Africa as early as the 8th century through the Trans-Saharan trade. Islam came to Harlem likely through the migration of members of the Moorish Science Temple of America, which was established in 1913 in New Jersey.[citation needed] Various forms of Judaism were practiced, including Orthodox, Conservative and Reform Judaism, but it was Black Hebrew Israelites that founded their religious belief system during the early 20th century in the Harlem Renaissance.[citation needed] Traditional forms of religion acquired from various parts of Africa were inherited and practiced during this era. Some common examples were Voodoo and Santeria.[citation needed]

Criticism

Religious critique during this era was found in music, literature, art, theater and poetry. The Harlem Renaissance encouraged analytic dialogue that included the open critique and the adjustment of current religious ideas.

One of the major contributors to the discussion of African-American renaissance culture was Aaron Douglas, who, with his artwork, also reflected the revisions African Americans were making to the Christian dogma. Douglas uses biblical imagery as inspiration to various pieces of artwork, but with the rebellious twist of an African influence.[33]

Countee Cullen's poem "Heritage" expresses the inner struggle of an African American between his past African heritage and the new Christian culture.[34] A more severe criticism of the Christian religion can be found in Langston Hughes's poem "Merry Christmas", where he exposes the irony of religion as a symbol for good and yet a force for oppression and injustice.[35]

Music

A new way of playing the piano called the Harlem Stride style was created during the Harlem Renaissance helping to blur the lines between the poor African Americans and socially elite African Americans. The traditional jazz band was composed primarily of brass instruments and was considered a symbol of the South, but the piano was considered an instrument of the wealthy. With this instrumental modification to the existing genre, the wealthy African Americans now had more access to jazz music. Its popularity soon spread throughout the country and was consequently at an all-time high.

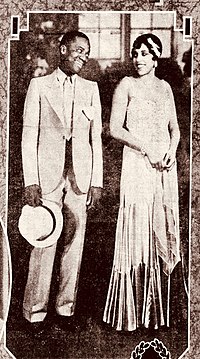

Innovation and liveliness were important characteristics of performers in the beginnings of jazz. Jazz performers and composers at the time such as Eubie Blake, Noble Sissle, Jelly Roll Morton, Luckey Roberts, James P. Johnson, Willie "The Lion" Smith, Andy Razaf, Fats Waller, Ethel Waters, Adelaide Hall,[36] Florence Mills and bandleaders Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Fletcher Henderson were extremely talented, skillful, competitive and inspirational. They laid great parts of the foundations for future musicians of their genre.[37][38][39]

Duke Ellington gained popularity during the Harlem Renaissance. According to Charles Garrett, "The resulting portrait of Ellington reveals him to be not only the gifted composer, bandleader, and musician we have come to know, but also an earthly person with basic desires, weaknesses, and eccentricities."[8] Ellington did not let his popularity get to him. He remained calm and focused on his music.

During this period, the musical style of blacks was becoming more and more attractive to whites. White novelists, dramatists and composers started to exploit the musical tendencies and themes of African Americans in their works. Composers (including William Grant Still, William L. Dawson and Florence Price) used poems written by African-American poets in their songs, and would implement the rhythms, harmonies and melodies of African-American music—such as blues, spirituals and jazz—into their concert pieces. African Americans began to merge with whites into the classical world of musical composition. The first African-American male to gain wide recognition as a concert artist in both his region and internationally was Roland Hayes. He trained with Arthur Calhoun in Chattanooga, and at Fisk University in Nashville. Later, he studied with Arthur Hubbard in Boston and with George Henschel and Amanda Ira Aldridge in London, England. Hayes began singing in public as a student, and he toured with the Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1911.[40]

Musical theatre

According to James Vernon Hatch and Leo Hamalian, all-black review, Run, Little Chillun, is considered one of the most successful musical dramas of the Harlem Renaissance.[41]

Fashion

During the Harlem Renaissance, the African-American clothing scene took a dramatic turn from the prim and proper many young women preferred, from short skirts and silk stockings to drop-waisted dresses and cloche hats.[42] Women wore loose-fitted garments and accessorized with long strand pearl bead necklaces, feather boas, and cigarette holders. The fashion of the Harlem Renaissance was used to convey elegance and flamboyancy and needed to be created with the vibrant dance style of the 1920s in mind.[43] Popular by the 1930s was a trendy, egret-trimmed beret.

Men wore loose suits that led to the later style known as the "Zoot", which consisted of wide-legged, high-waisted, peg-top trousers, and a long coat with padded shoulders and wide lapels. Men also wore wide-brimmed hats, colored socks,[44] white gloves and velvet-collared Chesterfield coats. During this period, African Americans expressed respect for their heritage through a fad for leopard-skin coats, indicating the power of the African animal.

While performing in Paris during the height of the Renaissance, the extraordinarily successful black dancer Josephine Baker was a major fashion trendsetter for black and white women alike. Her gowns from the couturier Jean Patou were copied, especially her stage costumes, which Vogue magazine called "startling". Josephine Baker is also credited for highlighting the "art deco" fashion era after she performed the "Danse Sauvage". During this Paris performance, she adorned a skirt made of string and artificial bananas. Ethel Moses was another popular black performer. Moses starred in silent films in the 1920s and 1930s and was recognizable by her signature bob hairstyle.

Photography

James Van Der Zee's photography played an important role in shaping and documenting the cultural and social life of Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance. His photographs were instrumental in shaping the image and identity of the African-American community during the Harlem Renaissance. His work documented the achievements of cultural figures and helped to challenge stereotypes and racist attitudes,[45] which in turn promoted pride and dignity among African Americans in Harlem and beyond.

Van Der Zee's studio was not just a place for taking photographs; it was also a social and cultural hub for Harlem residents.[46] People would come to his studio not only to have their portraits taken, but also to socialize and to participate in the community events that he hosted. Van Der Zee's studio played an important role in the cultural life of Harlem during the early 20th century, and helped to foster a sense of community and pride among its residents.

Some notable persons photographed are Marcus Garvey, the leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), a black nationalist organization that promoted Pan-Africanism and economic independence for African Americans. Other notable black persons he photographed are Countee Cullen, a poet and writer who was associated with the Harlem Renaissance; Josephine Baker, a dancer and entertainer who became famous in France and was known for her provocative performances; W. E. B. Du Bois, a sociologist, historian and civil rights activist who was a leading figure in the African-American community in the early 20th century; Langston Hughes, a poet, novelist and playwright who was one of the most important writers of the Harlem Renaissance; and Madam C.J. Walker, an entrepreneur and philanthropist who was one of the first African-American women to become a self-made millionaire, as well as her daughter, Dorthy Waring, an artist and author of 12 novels.

Van Der Zee's work gained renewed attention in the 1960s and 1970s, when interest in the Harlem Renaissance was revived. Van Der Zee's photographs have been featured in numerous exhibitions over the years. One notable exhibition was "Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968,"[47] which was organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1969. The exhibit included over 300 photographs, many of which were by Van Der Zee, and was one of the first major exhibitions to focus on the cultural achievements of African Americans in Harlem.

Van Der Zee's work was the eyes of Harlem. His photographs are recognized as important documents of African-American life and culture during the early 20th century. They serve as a visual record of the achievements of the Harlem Renaissance.[48] Kelli Jones called him "the official chronicler of the Harlem Renaissance."[49] His portraits of writers, musicians, artists and other cultural figures helped to promote their work and bring attention to the vibrant creative scene known as Harlem.

Painting

Aaron Douglas, born in Kansas in 1899 and often referred to as the "Father of African-American Art", is one of the most affluential painters of the Harlem Renaissance.[50] Through his paintings that utilize color, shape, and line, Douglas creates a collapsing of time as he merges the past, present, and future of American-American history. Fragmentation of the picture plane, geometry, and hard-edge abstraction are present in most of his paintings during the Harlem Renaissance. Douglas drew inspiration from both ancient Egyptian and Native American motifs.[50]

Sculpting

Augusta Savage, born in Florida in 1892, was a culture, advocate, and teacher during the Harlem Renaissance who put black everyday people at the forefront of her works. In 1932, Savage founded the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts, providing free art classes in painting, printmaking, and sculpting. She secured government funding for the school to train youths and adults. Known as a leading light within the Harlem community, Savage encouraged artists to seek financial compensation for their works, which led to the start of the Harlem Artist Guild in 1935. Augusta Savage was the only African American commissioned to create an exhibit for the 1939 World Fair in New York, where she showcased her piece Lift Every Voice and Sing, which quickly became one of the most popular pieces within the fair.[51]

Characteristics and themes

Characterizing the Harlem Renaissance was an overt racial pride that came to be represented in the idea of the New Negro, who through intellect and production of literature, art and music could challenge the pervading racism and stereotypes to promote progressive or socialist politics, and racial and social integration. The creation of art and literature would serve to "uplift" the race.

There would be no uniting form singularly characterizing the art that emerged from the Harlem Renaissance. Rather, it encompassed a wide variety of cultural elements and styles, including a Pan-African perspective, "high-culture" and "low-culture" or "low-life", from the traditional form of music to the blues and jazz, traditional and new experimental forms in literature such as modernism and the new form of jazz poetry. This duality meant that numerous African-American artists came into conflict with conservatives in the black intelligentsia, who took issue with certain depictions of black life.

Some common themes represented during the Harlem Renaissance were the influence of the experience of slavery and emerging African-American folk traditions on black identity, the effects of institutional racism, the dilemmas inherent in performing and writing for elite white audiences, and the question of how to convey the experience of modern black life in the urban North.

The Harlem Renaissance was one of primarily African-American involvement. It rested on a support system of black patrons and black-owned businesses and publications. However, it also depended on the patronage of white Americans, such as Carl Van Vechten and Charlotte Osgood Mason, who provided various forms of assistance, opening doors which otherwise might have remained closed to the publication of work outside the black American community. This support often took the form of patronage or publication. Carl Van Vechten was one of the most noteworthy white Americans involved with the Harlem Renaissance. He allowed for assistance to the black American community because he wanted racial sameness.

There were other whites interested in so-called "primitive" cultures, as many whites viewed black American culture at that time, and wanted to see such "primitivism" in the work coming out of the Harlem Renaissance. As with most fads, some people may have been exploited in the rush for publicity.

Interest in African-American lives also generated experimental but lasting collaborative work, such as the all-black productions of George Gershwin's opera Porgy and Bess, and Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein's Four Saints in Three Acts. In both productions the choral conductor Eva Jessye was part of the creative team. Her choir was featured in Four Saints.[52] The music world also found white band leaders defying racist attitudes to include the best and the brightest African-American stars of music and song in their productions.

The African Americans used art to prove their humanity and demand for equality. The Harlem Renaissance led to more opportunities for blacks to be published by mainstream houses. Many authors began to publish novels, magazines and newspapers during this time. The new fiction attracted a great amount of attention from the nation at large. Among authors who became nationally known were Jean Toomer, Jessie Fauset, Claude McKay, Zora Neale Hurston, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Omar Al Amiri, Eric D. Walrond and Langston Hughes.

Richard Bruce Nugent (1906–1987), who wrote "Smoke, Lilies, and Jade", made an important contribution, especially in relation to experimental form and LGBT themes in the period.[53]

The Harlem Renaissance helped lay the foundation for the post-World War II protest movement of the Civil Rights movement. Moreover, many black artists who rose to creative maturity afterward were inspired by this literary movement.

The Renaissance was more than a literary or artistic movement, as it possessed a certain sociological development—particularly through a new racial consciousness—through ethnic pride, as seen in the Back to Africa movement led by Jamaican Marcus Garvey. At the same time, a different expression of ethnic pride, promoted by W. E. B. Du Bois, introduced the notion of the "talented tenth". Du Bois wrote of the Talented Tenth:

The Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men. The problem of education, then, among Negroes must first of all deal with the Talented Tenth; it is the problem of developing the best of this race that they may guide the mass away from the contamination and death of the worst.[54]

These "talented tenth" were considered the finest examples of the worth of black Americans as a response to the rampant racism of the period. No particular leadership was assigned to the talented tenth, but they were to be emulated. In both literature and popular discussion, complex ideas such as Du Bois's concept of "twoness" (dualism) were introduced (see The Souls of Black Folk; 1903).[55] Du Bois explored a divided awareness of one's identity that was a unique critique of the social ramifications of racial consciousness. This exploration was later revived during the Black Pride movement of the early 1970s.

Influence

A new black identity

The Harlem Renaissance was successful in that it brought the black experience clearly within the corpus of American cultural history. Not only through an explosion of culture, but on a sociological level, the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance redefined how America, and the world, viewed African Americans. The migration of Southern blacks to the North changed the image of the African American from rural, undereducated peasants to one of urban, cosmopolitan sophistication. This new identity led to a greater social consciousness, and African Americans became players on the world stage, expanding intellectual and social contacts internationally.

The progress—both symbolic and real—during this period became a point of reference from which the African-American community gained a spirit of self-determination that provided a growing sense of both black urbanity and black militancy, as well as a foundation for the community to build upon for the Civil Rights struggles in the 1950s and 1960s.

The urban setting of rapidly developing Harlem provided a venue for African Americans of all backgrounds to appreciate the variety of black life and culture. Through this expression, the Harlem Renaissance encouraged the new appreciation of folk roots and culture. For instance, folk materials and spirituals provided a rich source for the artistic and intellectual imagination, which freed blacks from the establishment of past condition. Through sharing in these cultural experiences, a consciousness sprung forth in the form of a united racial identity.

However, there was some pressure within certain groups of the Harlem Renaissance to adopt sentiments of conservative white America in order to be taken seriously by the mainstream. The result being that queer culture, while far-more accepted in Harlem than most places in the country at the time, was most fully lived out in the smoky dark lights of bars, nightclubs and cabarets in the city.[56] It was within these venues that the blues music scene boomed, and, since it had not yet gained recognition within popular culture, queer artists used it as a way to express themselves honestly.[56]

Even though there were factions within the Renaissance that were accepting of queer culture/lifestyles, one could still be arrested for engaging in homosexual acts. Many people, including author Alice Dunbar Nelson and "The Mother of Blues" Gertrude "Ma" Rainey,[57] had husbands but were romantically linked to other women as well.[58]

Women and the LGBTQ community

During the Harlem Renaissance, various well-known figures, including Claude Mckay, Langston Hughes, and Ethel Waters, are believed to have had private same-gender relationships, although this aspect of their lives remained undisclosed to the public during that era.[59][60]

In the Harlem music scene, places such as the Cotton Club and Rockland Palace routinely held gay drag shows in addition to straight performances. Lesbian or bisexual women performers, such as blues singers Gladys Bentley and Bessie Smith, were a part of this cultural movement, which contributed to a renewed interest in African-American culture among the black community and introduced it to a wider audience.[61]

Although women's contributions to culture were often overlooked at the time, contemporary black feminist critics have endeavored to re-evaluate and recognize the cultural production of women during the Harlem Renaissance. Authors such as Nella Larsen and Jessie Fauset have gained renewed critical acclaim for their work from modern perspectives.[62]

Blues singer Gertrude "Ma" Rainey was known to dress in traditionally male clothing, and her blues lyrics often reflected her sexual proclivities for women, which was extremely radical at the time. Ma Rainey was also the first person to introduce blues music into vaudeville.[63] Rainey's protégé, Bessie Smith, was another artist who used the blues as a way to express unapologetic views on same-gender relations, with such lines as "When you see two women walking hand in hand, just look em' over and try to understand: They'll go to those parties – have the lights down low – only those parties where women can go."[56] Rainey, Smith, and artist Lucille Bogan were collectively known as "The Big Three of the Blues."[64]

Another prominent blues singer was Gladys Bentley, who was known to cross-dress. Bentley was the club owner of Clam House on 133rd Street in Harlem, which was a hub for queer patrons. The Hamilton Lodge in Harlem hosted an annual drag ball, drawing thousands of people to watch young men dance in drag. Though there were safe spaces within Harlem, there were prominent voices, such as that of Abyssinian Baptist Church's minister Adam Clayton Powell Sr., who actively opposed homosexuality.[58]

The Harlem Renaissance was instrumental in fostering the "New Negro" movement, an endeavor by African Americans to redefine their identity free from degrading stereotypes. The Neo-New Negro movement further challenged racial definitions, stereotypes, and gender norms and roles, seeking to address normative sexuality and sexism in American society.[65]

These ideas received some pushback, particularly regarding sexual freedom for women,[57] which was seen as confirming the stereotype that black women were sexually uninhibited. Some members of the black bourgeoisie saw this as hindering the overall progress of the black community and fueling racist sentiments. Yet queer culture and artists defined major portions of the Harlem Renaissance; Henry Louis Gates Jr., in a 1993 essay titled "The Black Man's Burden", wrote that the Harlem Renaissance "was surely as gay as it was black".[58][65]

Criticism of the movement

Many critics point out that the Harlem Renaissance could not escape its history and culture in its attempt to create a new one, or sufficiently separate from the foundational elements of white, European culture. Often Harlem intellectuals, while proclaiming a new racial consciousness, resorted to mimicry of their white counterparts by adopting their clothing, sophisticated manners and etiquette. This "mimicry" may also be called assimilation, as that is typically what minority members of any social construct must do in order to fit social norms created by that construct's majority.[66] This could be seen as a reason that the artistic and cultural products of the Harlem Renaissance did not overcome the presence of white-American values and did not reject these values.[citation needed] In this regard, the creation of the "New Negro", as the Harlem intellectuals sought, was considered a success.[by whom?]

The Harlem Renaissance appealed to a mixed audience. The literature appealed to the African-American middle class and to whites. Magazines such as The Crisis, a monthly journal of the NAACP, and Opportunity, an official publication of the National Urban League, employed Harlem Renaissance writers on their editorial staffs, published poetry and short stories by black writers, and promoted African-American literature through articles, reviews and annual literary prizes. However, as important as these literary outlets were, the Renaissance relied heavily on white publishing houses and white-owned magazines.[67]

A major accomplishment of the Renaissance was to open the door to mainstream white periodicals and publishing houses, although the relationship between the Renaissance writers and white publishers and audiences created some controversy. W. E. B. Du Bois did not oppose the relationship between black writers and white publishers, but he was critical of works such as Claude McKay's bestselling novel Home to Harlem (1928) for appealing to the "prurient demand[s]" of white readers and publishers for portrayals of black "licentiousness".[67]

Langston Hughes spoke for most of the writers and artists when he wrote in his essay "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain" (1926) that black artists intended to express themselves freely, no matter what the black public or white public thought.[68] Hughes in his writings also returned to the theme of racial passing, but, during the Harlem Renaissance, he began to explore the topic of homosexuality and homophobia. He began to use disruptive language in his writings. He explored this topic because it was a theme that during this time period was not discussed.[69]

African-American musicians and writers were among mixed audiences as well, having experienced positive and negative outcomes throughout the New Negro Movement. For musicians, Harlem, New York's cabarets and nightclubs shined a light on black performers and allowed for black residents to enjoy music and dancing. However, some of the most popular clubs (that showcased black musicians) were exclusively for white audiences; one of the most famous white-only nightclubs in Harlem was the Cotton Club, where popular black musicians like Duke Ellington frequently performed.[70] Ultimately, the black musicians who appeared at these white-only clubs became far more successful and became a part of the mainstream music scene.[citation needed]

Similarly, black writers were given the opportunity to shine once the New Negro Movement gained traction as short stories, novels and poems by black authors began taking form and getting into various print publications in the 1910s and 1920s.[71] Although a seemingly good way to establish their identities and culture, many authors note how hard it was for any of their work to actually go anywhere. Writer Charles Chesnutt in 1877, for example, notes that there was no indication of his race alongside his publication in Atlantic Monthly (at the publisher's request).[72]

A prominent factor in the New Negro's struggle was that their work had been made out to be "different" or "exotic" to white audiences, making a necessity for black writers to appeal to them and compete with each other to get their work out.[71] Famous black author and poet Langston Hughes explained that black-authored works were placed in a similar fashion to those of oriental or foreign origin, only being used occasionally in comparison to their white-made counterparts: Once a spot for a black work was "taken", black authors had to look elsewhere to publish.[72]

Certain aspects of the Harlem Renaissance were accepted without debate, and without scrutiny. One of these was the future of the "New Negro". Artists and intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance echoed American progressivism in its faith in democratic reform, in its belief in art and literature as agents of change, and in its almost uncritical belief in itself and its future. This progressivist worldview rendered black intellectuals—just like their white counterparts—unprepared for the rude shock of the Great Depression, and the Harlem Renaissance ended abruptly because of naïve assumptions about the centrality of culture, unrelated to economic and social realities.[73]

Works associated with the Harlem Renaissance

- Blackbirds of 1928

- Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance (book)

- The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke

- Shuffle Along, musical

- Untitled (The Birth), painting

- Voodoo (opera)

- When Washington Was in Vogue

- The Negro in Art

- Taboo (1922 play)

- There'll Be Some Changes Made

See also

- Black Arts Movement, 1960s and 1970s

- Black Renaissance in D.C.

- Chicago Black Renaissance

- List of female entertainers of the Harlem Renaissance

- List of figures from the Harlem Renaissance

- New Negro

- Niggerati

- William E. Harmon Foundation award

- Cotton Club, nightclub

General:

- Roaring Twenties

- African-American art

- African-American culture

- African-American literature

- List of African-American visual artists

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Chambers, Veronica; May-Curry, Michelle (21 March 2024). "The Dinner Party That Started the Harlem Renaissance". Archived from the original on 21 March 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "NAACP: A Century in the Fight for Freedom" Archived 1 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Library of Congress.

- ^ "Harlem in the Jazz Age". The New York Times. 8 February 1987. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (24 May 1998). "ART; A 1920s Flowering That Didn't Disappear". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "French Connection". Harlem Renaissance. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Kirka, Danica (1 January 1995). "Los Angeles Times Interview : Dorothy West : A Voice of Harlem Renaissance Talks of Past--But Values the Now". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Hutchinson, George. "Harlem Renaissance". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 19 May 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Project MUSE – Modernism, Mass Culture, and the Harlem Renaissance: The Case of Countee Cullen." Project MUSE – Modernism, Mass Culture, and the Harlem Renaissance: The Case of Countee Cullen. N.p., n.d. Web. 4 April 2015.

- ^ "Speeches of African-American Representatives Addressing the Ku Klux Klan Bill of 1871" (PDF). NYU Law. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Cooper Davis, Peggy. "Neglected Voices". NYU Law.

- ^ McGruder, Kevin (2 September 2021). Philip Payton. doi:10.7312/mcgr19892. ISBN 9780231552875.

- ^ Woods, Clyde (1998). Development Arrested. New York and London: Verso. ISBN 9781859848111.

- ^ Blackmon, Douglas A. (2009). Slavery By Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. Anchor.

- ^ Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. Harper Collins.

- ^ Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem; Obstfeld, Raymond (2007). On The Shoulders of Giants : My Journey Through the Harlem Renaissance. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 1–288. ISBN 978-1-4165-3488-4. OCLC 76168045.

- ^ "A Culture of Change - Boundless US History". 26 February 2024. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017.

- ^ Muhammad, Khalil Gibran (2010). The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-0-674-03597-3.

- ^ "Harlem Hellfighters: Black Soldiers in World War I". America Comes Alive. 5 February 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ McKay, Nellie Y., and Henry Louis Gates (eds), The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, New York: Norton, 1997, p. 931.

- ^ McKay, Claude (October 1917). ""Invocation" and "Harlem Dancer"". The Seven Arts. 2 (6): 741–742. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "The Harlem Renaissance". Amsterdam News. 9 February 2017. Archived from the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ "Library of America interviews Rafia Zafar about the Harlem Renaissance". Library of America. 26 August 2011. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ Poets, Academy of American Poets. "About Fenton Johnson". Poets. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ Foundation, Poetry (13 August 2021). "Fenton Johnson". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ Lewis, David Levering (1995). The Portable Harlem Renaissance Reader. Penguin Books. p. 752. ISBN 978-0-14-017036-8.

- ^ Langston, Hughes (1926). "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain". The Nation. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ Locke, Alain (1925). The New Negro. Touchstone. pp. ix.

- ^ Locke, Alain (1925). The New Negro. Touchstone.

- ^ Hughes, Langston (1926). The Weary Blues. New York: Random House.

- ^ Hughes, Langston (1994). The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes. Vintage Classics. pp. 307. ISBN 978-0679764083.

- ^ Williams, Robert M.; Carrington, Charles (May 1936). "Methodist Union and The Negro". The Crisis. 43 (5): 134–135.

- ^ a b MacWilliam, George Joseph (January 1920). "The Catholic Church and the Negro Priest". The Crisis. 19 (3): 122–123. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ Rampersad, Arnold (Introduction) (1997). Alain Locke (ed.). The New Negro: Voices of the Harlem Renaissance (1st Touchstone ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0684838311.

- ^ Cullen, Countee. "Heritage". Poetry Foundation. Archived from the original on 21 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Hughes, Langston (13 January 2010). "Merry Christmas". H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. New Masses. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ America, Harlem Renaissance in (5 December 2016). "The Harlem Renaissance". Harlem Renaissance in America Art History – via coreybarksdale.com.

- ^ Boland, Jesse. "Harlem Renaissance Music." 1920s Fashion and Music. Web. 23 November 2009.

- ^ "Harlem Renaissance Music in the 1920s", 1920s Fashion & Music.

- ^ Leonard Feather, "The Book of Jazz" (1957/59), p. 59 ff., Western Book Dist, 1988, ISBN 0818012021, 9780818012020

- ^ Southern, Eileen, Music of Negro Americans: a history. New York: Norton, 1997. Print, pp. 404, 405 and 409.

- ^ Hatch, James Vernon; Hamalian, Leo (1996). Lost plays of the Harlem Renaissance, 1920-1940. Internet Archive. Detroit : Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2580-3.

- ^ West, Aberjhani and Sandra L. (2003). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance, pp. 105–106; Vogue, 15 February 1926, p. 76.

- ^ Etherington-Smith, Meredith (1983), Patou, p. 83; Vogue, 1 June 1927, p. 51.

- ^ White, Shane and Graham (1998). Stylin': African American Expressive Culture from Its Beginnings to the Zoot Suit, pp. 248–251.

- ^ Cooks, Bridget R. (2007). "Black Artists and Activism: Harlem on My Mind (1969)". American Studies. 48 (1): 5–39. ISSN 0026-3079. JSTOR 40644000.

- ^ "GGG Photo Studio at Christmas | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Baum, Kellie; Robles, Maricelle; Yount, Silvia (17 February 2021). ""Harlem on Whose Mind?" The Met and Civil Rights". The Met. Archived from the original on 20 February 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Willis, Deborah (2003). "Visualizing Memory: Photographs and the Art of Biography". American Art. 17 (1): 20–23. doi:10.1086/444679. JSTOR 3109414. S2CID 192161995.

- ^ Jones, Kellie (2011). EyeMinded. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 195. ISBN 9780822348610.

- ^ a b Ragar, Cheryl R. (2010). "The Douglas Legacy". American Studies. 49 – via Mid-America American Studies Association.

- ^ Nelson, Marilyn; Lawson (2022). Augusta Savage: the shape of a sculptor's life (1st ed.). New York: Christy Ottaviano Books, Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 9780316298025.

- ^ "Eva Jessye", University of Michigan, accessed 4 December 2008.

- ^ Nugent, Bruce (2002). Wirth, Thomas H.; Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (eds.). Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance : Selections from the Work of Richard Bruce Nugent. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822328865. OCLC 48691374.

- ^ W.E.B. Du Bois, "The Talented Tenth" (text), Sep 1903, TeachingAmericanHistory.org, Ashland University, accessed 3 Sep 2008

- ^ It was possible for blacks to have intellectual discussions on whether black people had a future in America, and the Harlem Renaissance reflected such sociopolitical concerns.

- ^ a b c Hix, Lisa (9 July 2013). "Singing the Lesbian Blues in 1920s Harlem". Collectors Weekly.

- ^ a b Tenoria, Samantha (2006). "Women-Loving Women: Queering Black Urban Space during the Harlem Renaissance" (PDF). The University of California, Irvine (UCI) Undergraduate Research Journal. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Villarosa, Linda (23 July 2011). "The Gay Harlem Renaissance". The Root. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016.

- ^ Piercon, Jackson (2019). "LGBTQ Americans in the US Political System: An Encyclopedia of Activists, Voters, Candidates, and Officeholders". ABC-CLIO. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Balshaw, Maria (1999). "New Negroes, new women: The gender politics of the Harlem renaissance". Women: A Cultural Review. 10 (2): 127–138. doi:10.1080/09574049908578383. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Chen, Emma (2016). "Black Face, Queer Space: The Influence of Black Lesbian & Transgender Blues Women of the Harlem Renaissance on Emerging Queer Communities". Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II. 21 (8). Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Tenrio, Samantha (2010). "Women-Loving Women: Queering Black Urban Space during the Harlem Renaissance" (PDF). The UCI Undergraduate Research Journal: 33–44. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Garber, Eric. "A Spectacle in Color: The Lesbian and Gay Subculture of Jazz Age Harlem". American Studies at the University of Virginia. University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 17 April 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ Radesky, Carolyn (2019). "Harlem Renaissance". In Chiang, Howard (ed.). Global encyclopedia of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) history. Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 9781787859906.

- ^ a b Rabaka, Reiland (2011). Hip Hop's Inheritance From the Harlem Renaissance to the Hip Hop Feminist Movement. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739164822.

- ^ Yayla, Ayşegül. "Harlem Renaissance and its Discontents". Academia. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ a b Aptheker, H. ed. (1997), The Correspondence of WEB Dubois: Selections, 1877–1934[permanent dead link], Vol. 1, pp. 374–375.

- ^ Rampersad, Arnold (26 November 2001). The Life of Langston Hughes: Volume I: 1902-1941, I, Too, Sing America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199760862 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Project MUSE – Multiple Passings and the Double Death of Langston Hughes." Project MUSE – Multiple Passings and the Double Death of Langston Hughes. N.p., n.d. Web. 4 April 2015.

- ^ Davis, John S. (2012). Historical dictionary of jazz. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810878983. OCLC 812621902.

- ^ a b Werner, Craig; Golphin, Vincent F. A.; Reisman, Rosemary M. Canfield (2017), "African American Poetry", Salem Press Encyclopedia of Literature, Salem Press, retrieved 21 May 2019

- ^ a b Holmes, Eugene C. (1968). "Alain Locke and the New Negro Movement". Negro American Literature Forum. 2 (3): 60–68. doi:10.2307/3041375. ISSN 0028-2480. JSTOR 3041375.

- ^ Pawłowska, Aneta (2014). "The Ambivalence of African-American Culture. The New Negro Art in the interwar period". Art Inquiry. 16: 190 – via Google Scholar.

References

- Amos, Shawn, compiler. Rhapsodies in Black: Words and Music of the Harlem Renaissance. Los Angeles: Rhino Records, 2000. 4 Compact Discs.

- Andrews, William L.; Frances S. Foster; Trudier Harris, eds. The Concise Oxford Companion To African American Literature. New York: Oxford Press, 2001. ISBN 1-4028-9296-9

- Bean, Annemarie. A Sourcebook on African-American Performance: Plays, People, Movements. London: Routledge, 1999; pp. vii + 360.

- Greaves, William documentary From These Roots.

- Hicklin, Fannie Ella Frazier. "The American Negro Playwright, 1920–1964". PhD Dissertation, Department of Speech, University of Wisconsin, 1965. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms 65–6217.

- Huggins, Nathan. Harlem Renaissance. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973. ISBN 0-19-501665-3

- Hughes, Langston. The Big Sea. New York: Knopf, 1940.

- Hutchinson, George. The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White. New York: Belknap Press, 1997. ISBN 0-674-37263-8

- Lewis, David Levering, ed. The Portable Harlem Renaissance Reader. New York: Viking Penguin, 1995. ISBN 0-14-017036-7

- Lewis, David Levering. When Harlem Was in Vogue. New York: Penguin, 1997. ISBN 0-14-026334-9

- Ostrom, Hans. A Langston Hughes Encyclopedia. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2002.

- Ostrom, Hans and J. David Macey, eds. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of African American Literature. 5 volumes. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2005.

- Patton, Venetria K., and Maureen Honey, eds. Double-Take: A Revisionist Harlem Renaissance Anthology. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2006.

- Perry, Jeffrey B. A Hubert Harrison Reader. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001.

- Perry, Jeffrey B. Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883–1918. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

- Powell, Richard, and David A. Bailey, eds. Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

- Rampersad, Arnold. The Life of Langston Hughes. 2 volumes. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986 and 1988.

- Robertson, Stephen, et al., "Disorderly Houses: Residences, Privacy, and the Surveillance of Sexuality in 1920s Harlem", Journal of the History of Sexuality, 21 (September 2012), 443–66.

- Soto, Michael, ed. Teaching The Harlem Renaissance. New York: Peter Lang, 2008.

- Tracy, Steven C. Langston Hughes and the Blues. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988.

- Watson, Steven. The Harlem Renaissance: Hub of African-American Culture, 1920–1930. New York: Pantheon Books, 1995. ISBN 0-679-75889-5

- Williams, Iain Cameron. "Underneath a Harlem Moon ... The Harlem to Paris Years of Adelaide Hall". Continuum Int. Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0826458939

- Wintz, Cary D. Black Culture and the Harlem Renaissance. Houston: Rice University Press, 1988.

- Wintz, Cary D. Harlem Speaks: A Living History of the Harlem Renaissance. Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks, Inc., 2007

Further reading

- Brown, Linda Rae (1990). "William Grant Still, Florence Price, and William Dawson: Echoes of the Harlem Renaissance". In Samuel A. Floyd, Jr (ed.), Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance, Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, pp. 71–86.

- Buck, Christopher (2013). Harlem Renaissance in: The American Mosaic: The African American Experience. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

- Evans, Curtis J. (2008), The Burden of Black Religion, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-532931-5

- Johnson, Michael K. (2019), Can't Stand Still: Taylor Gordon and the Harlem Renaissance. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 9781496821966 (online)

- King, Shannon (2015). Whose Harlem Is This, Anyway? Community Politics and Grassroots Activism during the New Negro Era. New York University Press.

- Lassieur, Alison. (2013). The Harlem Renaissance: An Interactive History Adventure, North Mankato, Minnesota: Capstone Press, ISBN 9781476536095

- Murrell, Denise (2018). Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Murrell, Denise, ed. (2024). The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism. Exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588397737

- Padva, Gilad (2014). "Black Nostalgia: Poetry, Ethnicity, and Homoeroticism in Looking for Langston and Brother to Brother". In Padva, Gilad, Queer Nostalgia in Cinema and Pop Culture, pp. 199–226. Basingstoke, UK, and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wall, Cheryl A. (2016). The Harlem Renaissance: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Wintz, Cary D., and Paul Finkelman (2012). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. London: Routledge.

External links

- "A Guide to Harlem Renaissance Materials", from the Library of Congress

- Bryan Carter (ed.). "Virtual Harlem". University of Illinois at Chicago, Electronic Visualization Laboratory. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- "The Approaching 100th Anniversary of the Harlem Renaissance", by HR historian Aberjhani

- Underneath A Harlem Moon by Iain Cameron Williams ISBN 0-8264-5893-9

- I'd Like to Show You Harlem – by Rollin Lynde Hartt, The Independent, April, 1921

- Collection: "Artists of the Harlem Renaissance" from the University of Michigan Museum of Art

- The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 25 – July 28, 2024.

- Articles in The New York Times on the Harlem Renaissance, including on the 2024 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art