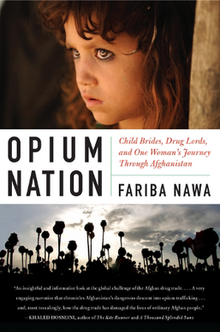

Opium Nation

| |

| Author | Fariba Nawa |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Harper Perennial |

Publication date | November 8, 2011 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | paperback |

| Pages | 368 |

| ISBN | 0-06210-061-0 |

| OCLC | 773581436 |

| 920 958.104/7 | |

Opium Nation: Child Brides, Drug Lords, and One Woman's Journey Through Afghanistan is a 2011 book by Fariba Nawa. The author travels throughout Afghanistan to talk with individuals part of the opium production in Afghanistan, centering on women's role in it.[1] Generally, reviewers felt that the book succeeded in its portrayal of Afghan culture and the impact of the opium trade on Afghans.

Synopsis

[edit]Born in Herat, Afghanistan, nine-year-old Nawa escaped in 1982 with her family during the Soviet–Afghan War. Following 18 years of separation from her homeland, Nawa visits the country in 2000 after the Taliban's rise to power[2] in an attempt to harmonize her American and Afghan identities.[3] Fluent in the dialect Dari Persian, she finds that she has difficulty comprehending the speech of people in her hometown Herat because Iranian words and idioms have seeped into their language.[4] She spends seven years in the country attempting to comprehend and write about its changes.[5] In 2002, she moves to Kabul, serving as a journalist reporting on the War in Afghanistan that began in 2001.[6] From 2002 to 2007, she researches opium production in Afghanistan for her book.[4] In her first visit, she finds that her gorgeous childhood memories are obscured by bleak actualities. Taliban leaders have suppressed inhabitants' aesthetic and academic ambitions.[5]

Nawa discusses opium trafficking in Afghanistan, a trade she said is valued at $4 billion in the country and $65 billion outside it. 60% of Afghanistan's GDP comes from opium, of which two-thirds is distilled into heroin, a more potent drug. Because the distillation requires cooking, the traffickers allow women to take part in it. A large number of women and their families are beholden to opium. About 10–25% of women and children are speculated to be addicted to the drug. Many families serve in the opium enterprise as "opium farmers, refiners, or smugglers".[7]

Nawa describes the story of Darya, a 12-year-old opium bride in the Ghoryan district given by her father to a creditor 34 years her senior to liquidate his opium debts. The girl is initially resistant to the marriage, telling Nawa, "I do not want to go with this man. Can you please help me?"[2] She ultimately concedes to her father's wishes and marries the smuggler who lives hours away. After several months of no contact between Darya and the family, her mother beseeches Nawa to search for her.[7] Nawa attempts to find the child, saying, "I was immediately attracted to the young girl because she was a mystery and a victim who needed to be saved from barbaric traditions. I thought it was my job as an outsider from the West to rescue her."[5] But ultimately, she must give up because of danger from the child's husband and because the search takes her to the Helmand Province, a perilous place.[6][8] Nawa believes that Darya will save herself by standing up to her husband, escaping him, or discovering how to cope with her situation. She writes, "Darya offers hope for change. I will always want to know what happened to her, and perhaps someday I will."[8]

Nawa reveals the story of an uncle who kidnaps a six-year-old boy and his friend in Takhar Province, an attempt to coerce the boy's father to settle an opium debt. When the debt is not settled, the boy disappears and his friend's body is found after several days in a river.[6]

She discusses the positive economic impact the opium industry has had on some families. For one woman, poppy cultivation allowed her to buy a taxi for her son and a carpet frame for her daughter. Some newly affluent farmers use some of the wealth to improve the infrastructure of their neighborhoods.[9]

At the book's end, she reveals that she has married Naeem Mazizian, whom she had met at the Herat chapter of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. In 2005, he moves to Kabul. Following four years of companionship, they marry and have a daughter, Bonoo Zahra.[10] Nawa dedicated the book to her daughter and her parents, Sayed Begum and Fazul Haq.[11]

Style

[edit]"Part personal memoir and part history", the book delves into the elements of Afghanistan society seldom seen or comprehended by outsiders. The Canberra Times reviewer Bron Sibree called the book a "unique, finely distilled, intense perspective" that was "surprisingly frank and intimate" because women confide in her beliefs they do not tell other people.[6] The book is packed with numerous facts and numbers pertaining to the swell in the drug business. Sibree noted that the narrative is filled with accounts of Afghan history, particularly its traditions and its elegant, multifarious landscapes. Sibree opined that Nawa's intense depiction of the Afghanis, notably the women who are unflappable notwithstanding their adversity, are etched into the mind even after an extended period of time.[6]

Reception

[edit]Sharing remarkable stories of poppy farmers, corrupt officials, expats, drug lords, and addicts, including her haunting encounter with a twelve-year-old child bride who was bartered to pay off her father's opium debts, Nawa unveils a startling portrait of a land in turmoil as she courageously explores her own Afghan American identity.

Kirkus Reviews praised Nawa for deftly depicting the "tragic complexity of Afghan society and the sheer difficulty of life there". The reviewer found parts of the book's dialogue to be contrived but noted that Nawa's convincing narrative "clearly stems from in-depth reporting in a risk-laden environment".[13] Novelist Khaled Hosseini, author of The Kite Runner and A Thousand Splendid Suns praised the book for having a "very engaging narrative" and being "[a]n insightful and informative look at the global challenge of Afghan drug trade".[14] Writing for The Sun-Herald, author Lucy Sussex called the book "strong, informative reading".[3]

Publishers Weekly noted that Nawa "draws rich, complex portraits of subjects on both sides of the law". The review said the book is notable for its "depth, honesty, and commitment" to chronicling women's thoughts regarding their role in the drug trade, placing her life in jeopardy to collect the women's stories. Nawa, the review noted, "writes with passion about the history of her volatile homeland and with cautious optimism about its future".[15] Kate Tuttle of The Boston Globe commended the book for its "detailed, sensitive reporting of individual people's stories" and the author for her "clear-eyed reckoning with a country and a people who are beyond her help".[5] Writing in The Guardian, investigative journalist Pratap Chatterjee found that the book "reminds us that Afghanistan is not just a war, but a country of many ordinary yet unique people, kind and cruel, rich and poor".[16]

In February 2012, Opium Nation ranked seventh in the "independent" section of The Newcastle Herald's bestseller list.[17]

References

[edit]- Footnotes

- ^ Martin, Michel (2011-12-05). "The Future Of Women's Rights In Afghanistan". NPR. Archived from the original on 2012-07-03. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ a b Schurmann, Peter (2011-12-23). "'Opium Nation' -- The Women of Afghanistan's Drug Trade". New America Media. Archived from the original on 2012-07-03. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ a b Sussex, Lucy (2011-12-04). "Opium Nation". The Sun-Herald. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ a b Nawa, Fariba (2012-01-25). "How Iran Controls Afghanistan". Fox News. Archived from the original on 2012-07-03. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ a b c d Tuttle, Kate (2011-11-27). "'Cool, calm & contentious,' 'Opium Nation,' 'Hedy's Folly'". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 2012-07-03. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ a b c d e Sibree, Bron (2012-02-11). "A Nation Addicted to Opium Trade". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ a b Abdallah, Joanna (2012-01-10). "Opium Nation: Child Brides, Drug Lords, and One Woman's Journey Through Afghanistan". Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Archived from the original on 2012-07-03. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ a b Nawa 2011, p. 202

- ^ "A casualty of the Afghan opium trade". The Times of Central Asia. Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. 2012-02-29. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ Nawa 2011, p. 206

- ^ Nawa 2011, p. 2

- ^ "Best Bets, Nov. 13, 2011: Opium Nation literary reading". Santa Cruz Sentinel. 2011-11-13. Archived from the original on 2012-07-03. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ "Opium Nation". Kirkus Reviews. 2011-08-28. Archived from the original on 2011-11-06. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

- ^ Azizian, Naeem (2011). "Opium Nation | Fariba Nawa". Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ "Nonfiction review: Opium Nation". Publishers Weekly. 2011-08-08. Archived from the original on 2012-07-03. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ Chatterjee, Pratap (2012-04-01). "Travel: Opium Nation". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2012-07-03. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ "Best Sellers - Books". The Newcastle Herald. 2012-02-04. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- Bibliography