Pachydectes

| Pachydectes Temporal range: Middle Permian,

| |

|---|---|

| |

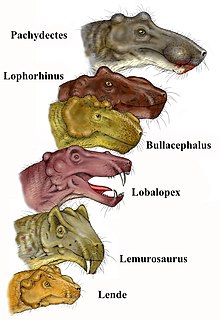

| Pachydectes (above) and other burnetiamorphs | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Biarmosuchia |

| Family: | †Burnetiidae |

| Genus: | †Pachydectes Rubidge et al., 2006 |

| Species: | †P. elsi

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Pachydectes elsi Rubidge et al., 2006

| |

Pachydectes is an extinct genus of biarmosuchian therapsids from the Middle Permian of South Africa known from a single skull.[1] The etymology of the name Pachydectes is derived from the Greek word pakhus, meaning "thick" or "thickened", and dektes, meaning "biter". In conjunction this name is representative of the unique pachyostotic bone present above the maxillary canine tooth found in the skull of the specimen.[1] There is only one known species within the genus, Pachydectes elsi which is named in honor of the person who discovered the fossil.

The holotype and only known specimen was found just above the Ecca-Beaufort contact in the eastern Karoo basin, which was a fluvial depositional environment.[2][3] As a member of the clade Biarmosuchia, Pachydectes retains many basal therapsid features, though with unique specializations one of which is the presence of adornments on the skull with horn-like protuberances.[1] Also as a member of this clade Pachydectes is thought to be carnivorous.

History and discovery

[edit]Pachydectes was initially discovered in 1997 during road construction being collected from just above the Ecca-Beaufort boundary in the Jansenville District of the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa, taking the form of a skull though missing the dentary.[1] The initial description of the taxon by Rudbride and Sidor based on the large maxillary caniniform teeth, a preparietal, and traces of large bosses on the skull roof took place in 2006.[1] Initially, using cladistic analysis and stratigraphic distribution Pachydectes was thought to be the sister taxon of Bullacephalus with the two collectively comprising the clade Burnetiidae.[1] With the discovery of new members of the clade by Day in 2016 and 2018, Day concluded that Pachydectes and Bullacephalus formed a different clade which they called Bullacephalidae which diverged before Burnetiamorpha entirely.[4] Subsequently Kammerer and Sidor have composed a reanalysis of the relationships between Burnetiamorphs with the discovery of Mobaceras zambeziense showing similarities to the Bullacephalus providing further evidence that Pachydectes is in fact a member of the clade Burnetiid as proposed originally.[5]

Description

[edit]The preserved specimen is a laterally compressed skull with no lower jaw measuring 310 mm in length.[1] Pachydectes still has a great deal of ancestral therapsid traits including the convex nature of the skull roof with a deep snout as well as a wide temporal roof. Due to the extensive weathering and lateral compression, the premaxilla and septomaxilla are difficult to decipher information from; however, the portions of the skull of the surrounding area do not differ greatly. The maxilla supports a large boss with an elongate bulbous dorsal extension. There are no pre-canine maxillary teeth consistent with primitive therapsids. Pachydectes supports a knoblike thickening just below the postorbital similarly to other burnetiamorphs with a thickened boss present just above the postorbital bar, where the postorbital contacts the postfrontal.[5] Distinct tear drop shaped boss posterior to the pineal foramen ending in a pointed tip.[6] The distinguishing trait is a conspicuous pachyostotic maxillary boss that sheathes the root of the upper canine.[1]

Paleobiology

[edit]The primary traits that have discernible ecological significance are the large caniniform teeth present on the maxilla and the previously mentioned series of large bosses and protuberance on the skull roof.[1] Pachyostosis is common both for protecting the brain during sexual displays in the case of head-butting or other forms of combat for reproductive success.[7] Conspicuous ornamentation with skull bosses, such as in Pachydectes, can be used as sexual display structures in a different capacity. Rather than combat, these "display structures" taking the form of cranial bosses can be a tool in intraspecific competition for mates.[7] However, a study of the maxillary canal morphology of Pachydectes did find that the cranial bosses could have been used for low-energy combat.[8]

The other trait, caniniform teeth, are a key indicator that Pachydectes was carnivorous.[1] This is because of the advantage that this form of teeth have to tear through flesh rather than having a grinding surface as would be expected in an herbivore. This is contrasted with the weathering and erosion of the fossilized specimen leading to a lack of clarity in the attachment of the jaw adductor musculature which prevents from complete understanding of the closure mechanism.[1]

Paleoenvironment and stratigraphic range

[edit]It is difficult to place the geographic distribution of Pachydectes as only one specimen has ever been discovered however, being that the skull was found in the Karoo Basin in South Africa, Pachydectes was at the very least found in southern Gondwana. The soil composition of shales and mudstones appears to imply a fluvial environment.[9][10] Based on reconstructive models of the positioning of the continents at the time he latitudinal position of the current Karoo Basin is consistent with it being in a more temperate region.[11] It is thought that a series of meandering rivers and or large river deltas could be responsible for the deposition and transfer of nutrients and moisture inland creating a variety of rich habitats resulting in the tremendous diversity in the region. Pachydectes may have lived in this paleoenvironment, potentially preying upon smaller vertebrates and using its pachyostotic bosses to signal to other members of its species.

Similarly to the geographic distribution, the stratigraphic range is difficult to determine as there is one known location that the species has been found that being just above the Ecca-Beaufort contact in the eastern Karoo basin. This means that the stratigraphic distribution is partially determined with the use of a strict consensus tree of therapsids. Being specifically from the Beaufort group means that the Pachydectes was present solely during the Guadalupian, specifically during the Wordian and Capitanian without being found anywhere else.[1]

Classification

[edit]Pachydectes is a genus in the family Burnetiidae as well as a sub clade Burnetiinae. The family Burnettidae falls into the suborder Burnetiamorph which was initially described in 1923 by Broom and is from the Middle Permian exclusively. The sister taxa of Pachydectes are Bullacephalus, Mobaceras, Burnetia, and Niuksenitia all of which are in a polytomy and are part of the clade Burnetiinae which diverged from Proburnetiinae, both of which form Burnetiidae.[5]

| Burnetiamorpha |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This cladogram is based on the phylogeny described in Kammerer 2021 in which the most recent analysis of Burnetiamoph relationships has come to the conclusion of the figure above.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Rubidge, B.S.; Sidor, C.A.; Modesto, S.P. (2006). "A new burnetiamorph (Therapsida: Biarmosuchia) from the Middle Permian of South Africa". Journal of Paleontology. 80 (4): 740–749. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2006)80[740:ANBTBF]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 130196490.

- ^ Rubidge BS, Hancox JP, Mason R. Waterford Formation in the south-eastern Karoo: Implications for basin development. S Afr J Sci. 2012;108(3/4), Art. #829, 5 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajs.v108i3/4.829

- ^ Rubidge, Bruce, S (2001). "Evolutionary Patterns among Permo-Triassic Therapsids". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 32: 449–480. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114113. JSTOR 2678648 – via JSTOR.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Day, Michael; Rubidge, Bruce; Abdala, Fernando (2016). "A new mid-Permian burnetiamorph therapsid from the Main Karoo Basin of South Africa and a phylogenetic review of Burnetiamorpha". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61. doi:10.4202/app.00296.2016. ISSN 0567-7920. S2CID 54666788.

- ^ a b c d Kammerer, Christian (13 January 2021). "A new burnetiid from the middle Permian of Zambia and a reanalysis of burnetiamorph relationships". Papers in Palaeontology. 7 (3): 1261–1295. doi:10.1002/spp2.1341. S2CID 232063704 – via wiley online library.

- ^ Kammerer, Christian F. (2016). "Two unrecognised burnetiamorph specimens from historic Karoo collections". Palaeontologia Africana. hdl:10539/20045. ISSN 2410-4418.

- ^ a b Benoit, Julien; Kruger, Ashley; Jirah, Sifelani; Fernandez, Vincent; Rubidge, Bruce (2021). "Palaeoneurology and palaeobiology of the dinocephalian Anteosaurus magnificus". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 66. doi:10.4202/app.00800.2020. ISSN 0567-7920. S2CID 234140235.

- ^ Benoit, Julien; Araujo, Ricardo; Lund, Erin S.; Bolton, Andrew; Lafferty, Tristen; Macungo, Zanildo; Fernandez, Vincent (April 2024). "Early synapsids neurosensory diversity revealed by CT and synchrotron scanning". The Anatomical Record. doi:10.1002/ar.25445. PMID 38600433. Retrieved 12 December 2024 – via ResearchGate.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Smith, R. M. H. (1995-08-01). "Changing fluvial environments across the Permian-Triassic boundary in the Karoo Basin, South Africa and possible causes of tetrapod extinctions". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 117 (1): 81–104. Bibcode:1995PPP...117...81S. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(94)00119-S. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Almond, John (March 2009). "PALAEONTOLOGICAL HERITAGE OF THE EASTERN CAPE". Sahra Technical Report.

- ^ Zhu, Zhicai; Liu, Yongqing; Kuang, Hongwei; Benton, Michael J.; Newell, Andrew J.; Xu, Huan; An, Wei; Ji, Shu’an; Xu, Shichao; Peng, Nan; Zhai, Qingguo (2019-11-14). "Altered fluvial patterns in North China indicate rapid climate change linked to the Permian-Triassic mass extinction". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 16818. Bibcode:2019NatSR...916818Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53321-z. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6856103. PMID 31727990. S2CID 207988180.