Angiotensin-converting enzyme

Angiotensin-converting enzyme monomer, Drosophila melanogaster | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC no. | 3.4.15.1 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9015-82-1 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (EC 3.4.15.1), or ACE, is a central component of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS), which controls blood pressure by regulating the volume of fluids in the body. It converts the hormone angiotensin I to the active vasoconstrictor angiotensin II. Therefore, ACE indirectly increases blood pressure by causing blood vessels to constrict. ACE inhibitors are widely used as pharmaceutical drugs for treatment of cardiovascular diseases.[5]

Other lesser known functions of ACE are degradation of bradykinin,[6] substance P[7] and amyloid beta-protein.[8]

Nomenclature

[edit]ACE is also known by the following names:

- dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase I

- peptidase P

- dipeptide hydrolase

- peptidyl dipeptidase

- angiotensin converting enzyme

- kininase II

- angiotensin I-converting enzyme

- carboxycathepsin

- dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase

- "hypertensin converting enzyme" peptidyl dipeptidase I

- peptidyl-dipeptide hydrolase

- peptidyldipeptide hydrolase

- endothelial cell peptidyl dipeptidase

- peptidyl dipeptidase-4

- PDH

- peptidyl dipeptide hydrolase

- DCP

- CD143

Function

[edit]ACE hydrolyzes peptides by the removal of a dipeptide from the C-terminus. Likewise it converts the inactive decapeptide angiotensin I to the octapeptide angiotensin II by removing the dipeptide His-Leu.[9]

ACE is a central component of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS), which controls blood pressure by regulating the volume of fluids in the body.

Angiotensin II is a potent vasoconstrictor in a substrate concentration-dependent manner.[10] Angiotensin II binds to the type 1 angiotensin II receptor (AT1), which sets off a number of actions that result in vasoconstriction and therefore increased blood pressure.

ACE is also part of the kinin–kallikrein system where it degrades bradykinin, a potent vasodilator, and other vasoactive peptides.[12]

Kininase II is the same as angiotensin-converting enzyme. Thus, the same enzyme (ACE) that generates a vasoconstrictor (ANG II) also disposes of vasodilators (bradykinin).[11]

Mechanism

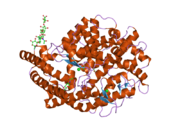

[edit]ACE is a zinc metalloproteinase.[13] The zinc center catalyses the peptide hydrolysis. Reflecting the critical role of zinc, ACE can be inhibited by metal-chelating agents.[14]

The E384 residue is mechanistically critical. As a general base, it deprotonates the zinc-bound water, producing a nucleophilic Zn-OH center. The resulting ammonium group then serves as a general acid to cleave the C-N bond.[16]

The function of the chloride ion is very complex and is highly debated. The anion activation by chloride is a characteristic feature of ACE.[17] It was experimentally determined that the activation of hydrolysis by chloride is highly dependent on the substrate. While it increases hydrolysis rates for e.g. Hip-His-Leu it inhibits hydrolysis of other substrates like Hip-Ala-Pro.[16] Under physiological conditions the enzyme reaches about 60% of its maximal activity toward angiotensin I while it reaches its full activity toward bradykinin. It is therefore assumed that the function of the anion activation in ACE provides high substrate specificity.[17] Other theories say that the chloride might simply stabilize the overall structure of the enzyme.[16]

Genetics

[edit]The ACE gene, ACE, encodes two isozymes. The somatic isozyme is expressed in many tissues, mainly in the lung, including vascular endothelial cells, epithelial kidney cells, and testicular Leydig cells, whereas the germinal is expressed only in sperm. Brain tissue has ACE enzyme, which takes part in local RAS and converts Aβ42 (which aggregates into plaques) to Aβ40 (which is thought to be less toxic) forms of beta amyloid. The latter is predominantly a function of N domain portion on the ACE enzyme. ACE inhibitors that cross the blood–brain barrier and have preferentially selected N-terminal activity may therefore cause accumulation of Aβ42 and progression of dementia.[citation needed]

Disease relevance

[edit]ACE inhibitors are widely used as pharmaceutical drugs in the treatment of conditions such as high blood pressure, heart failure, diabetic nephropathy, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

ACE inhibitors inhibit ACE competitively.[18] That results in the decreased formation of angiotensin II and decreased metabolism of bradykinin, which leads to systematic dilation of the arteries and veins and a decrease in arterial blood pressure. In addition, inhibiting angiotensin II formation diminishes angiotensin II-mediated aldosterone secretion from the adrenal cortex, leading to a decrease in water and sodium reabsorption and a reduction in extracellular volume.[19]

ACE's effect on Alzheimer's disease is still highly debated. Alzheimer patients usually show higher ACE levels in their brain. Some studies suggest that ACE inhibitors that are able to pass the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) could enhance the activity of major amyloid-beta peptide degrading enzymes like neprilysin in the brain resulting in a slower development of Alzheimer's disease.[20] More recent research suggests that ACE inhibitors can reduce risk of Alzheimer's disease in the absence of apolipoprotein E4 alleles (ApoE4), but will have no effect in ApoE4- carriers.[21] Another more recent hypothesis is that higher levels of ACE can prevent Alzheimer's. It is assumed that ACE can degrade beta-amyloid in brain blood vessels and therefore help prevent the progression of the disease.[22]

A negative correlation between the ACE1 D-allele frequency and the prevalence and mortality of COVID-19 has been established.[23]

Pathology

[edit]- Elevated levels of ACE are also found in sarcoidosis, and are used in diagnosing and monitoring this disease. Elevated levels of ACE are also found in leprosy, hyperthyroidism, acute hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, multiple myeloma, osteoarthritis, amyloidosis, Gaucher disease, pneumoconiosis, histoplasmosis and miliary tuberculosis. It is also noted in some patients with extensive plaque psoriasis.

- Serum levels are decreased in renal disease, obstructive pulmonary disease, and hypothyroidism.

Influence on athletic performance

[edit]The angiotensin converting enzyme gene has more than 160 polymorphisms described as of 2018.[24]

Studies have shown that different genotypes of angiotensin converting enzyme can lead to varying influence on athletic performance.[25][26] However, these data should be interpreted with caution due to the relatively small size of the investigated groups.

The rs1799752 I/D polymorphism (aka rs4340, rs13447447, rs4646994) consists of either an insertion (I) or deletion (D) of a 287 base pair sequence in intron 16 of the gene.[24] The DD genotype is associated with higher plasma levels of the ACE protein, the DI genotype with intermediate levels, and II with lower levels.[24] During physical exercise, due to higher levels of the ACE for D-allele carriers, hence higher capacity to produce angiotensin II, the blood pressure will increase sooner than for I-allele carriers. This results in a lower maximal heart rate and lower maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max). Therefore, D-allele carriers have a 10% increased risk of cardiovascular diseases. Furthermore, the D-allele is associated with a greater increase in left ventricular growth in response to training compared to the I-allele.[27] On the other hand, I-allele carriers usually show an increased maximal heart rate due to lower ACE levels, higher maximum oxygen uptake and therefore show an enhanced endurance performance.[27] The I allele is found with increased frequency in elite distance runners, rowers and cyclists. Short distance swimmers show an increased frequency of the D-allele, since their discipline relies more on strength than endurance.[28][29]

History

[edit]The enzyme was reported by Leonard T. Skeggs Jr. in 1956.[30] The crystal structure of human testis ACE was solved in the year 2002 by Ramanathan Natesh in the lab of K. Ravi Acharya in collaboration with Sylva Schwager and Edward Sturrock who purified the protein.[15] It is located mainly in the capillaries of the lungs but can also be found in endothelial and kidney epithelial cells.[31]

See also

[edit]- ACE inhibitors

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)

- Hypotensive transfusion reaction

- Renin–angiotensin system

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000159640 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000020681 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Kaplan's Essentials of Cardiac Anesthesia. Elsevier. 2018. doi:10.1016/c2012-0-06151-0. ISBN 978-0-323-49798-5.

Mechanisms of Action:ACE inhibitors act by inhibiting one of several proteases responsible for cleaving the decapeptide Ang I to form the octapeptide Ang II. Because ACE is also the enzyme that degrades bradykinin, ACE inhibitors increase circulating and tissue levels of bradykinin (Fig. 8.4).

- ^ Fillardi PP (2015). ACEi and ARBS in Hypertension and Heart Failure. Vol. 5. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. pp. 10–13. ISBN 978-3-319-09787-9.

- ^ Dicpinigaitis PV (January 2006). "Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines". Chest. 129 (1 Suppl): 169S – 173S. doi:10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.169S. PMID 16428706.

- ^ Hemming ML, Selkoe DJ (November 2005). "Amyloid beta-protein is degraded by cellular angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and elevated by an ACE inhibitor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (45): 37644–37650. doi:10.1074/jbc.M508460200. PMC 2409196. PMID 16154999.

- ^ Coates D (June 2003). "The angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE)". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. Renin–Angiotensin Systems: State of the Art. 35 (6): 769–773. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00309-6. PMID 12676162.

- ^ Zhang R, Xu X, Chen T, Li L, Rao P (May 2000). "An assay for angiotensin-converting enzyme using capillary zone electrophoresis". Analytical Biochemistry. 280 (2): 286–290. doi:10.1006/abio.2000.4535. PMID 10790312.

- ^ a b "Integration of Salt and Water Balance". Medical Physiology: a Cellular and Molecular Approach. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders. 2005. pp. 866–867. ISBN 978-1-4160-2328-9.

- ^ Imig JD (March 2004). "ACE Inhibition and Bradykinin-Mediated Renal Vascular Responses: EDHF Involvement". Hypertension. 43 (3): 533–535. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000118054.86193.ce. PMID 14757781.

- ^ Wang W, McKinnie SM, Farhan M, Paul M, McDonald T, McLean B, et al. (August 2016). "Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 Metabolizes and Partially Inactivates Pyr-Apelin-13 and Apelin-17: Physiological Effects in the Cardiovascular System". Hypertension. 68 (2): 365–377. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06892. PMID 27217402. S2CID 829514.

- ^ Bünning P, Riordan JF (July 1985). "The functional role of zinc in angiotensin converting enzyme: implications for the enzyme mechanism". Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 24 (3): 183–198. doi:10.1016/0162-0134(85)85002-9. PMID 2995578.

- ^ a b Natesh R, Schwager SL, Sturrock ED, Acharya KR (January 2003). "Crystal structure of the human angiotensin-converting enzyme-lisinopril complex". Nature. 421 (6922): 551–554. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..551N. doi:10.1038/nature01370. PMID 12540854. S2CID 4137382. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Zhang C, Wu S, Xu D (June 2013). "Catalytic mechanism of angiotensin-converting enzyme and effects of the chloride ion". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 117 (22): 6635–6645. doi:10.1021/jp400974n. PMID 23672666.

- ^ a b Bünning P (1983). "The catalytic mechanism of angiotensin converting enzyme". Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. Part A, Theory and Practice. 5 (7–8): 1263–1275. doi:10.3109/10641968309048856. PMID 6315268.

- ^ "Angiotensin converting enzyme (ace) inhibitors" (PDF). British Hypertension Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2017.

- ^ Klabunde RE. "ACE-inhibitors". Cardiovascular Pharmacology Concepts. cvpharmacology.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- ^ "The Importance of Treating the Blood Pressure: ACE Inhibitors May Slow Alzheimer's Disease". Medscape. Medscape Cardiology. 2004. Archived from the original on 31 August 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ^ Qiu WQ, Mwamburi M, Besser LM, Zhu H, Li H, Wallack M, et al. (1 January 2013). "Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and the reduced risk of Alzheimer's disease in the absence of apolipoprotein E4 allele". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 37 (2): 421–428. doi:10.3233/JAD-130716. PMC 3972060. PMID 23948883.

- ^ "ACE Enzyme May Enhance Immune Responses And Prevent Alzheimer's". Science 2.0. 27 August 2014. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ^ Delanghe JR, Speeckaert MM, De Buyzere ML (June 2020). "The host's angiotensin-converting enzyme polymorphism may explain epidemiological findings in COVID-19 infections". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 505: 192–193. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.031. PMC 7102561. PMID 32220422.

- ^ a b c Cintra MT, Balarin MA, Tanaka SC, Silva VI, Marqui AB, Resende EA, et al. (November 2018). "Polycystic ovarian syndrome: rs1799752 polymorphism of ACE gene". Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira. 64 (11): 1017–1022. doi:10.1590/1806-9282.64.11.1017. PMID 30570054.

- ^ Flück M, Kramer M, Fitze DP, Kasper S, Franchi MV, Valdivieso P (8 May 2019). "Cellular Aspects of Muscle Specialization Demonstrate Genotype - Phenotype Interaction Effects in Athletes". Frontiers in Physiology. 10: 526. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00526. PMC 6518954. PMID 31139091.

- ^ Wang P, Fedoruk MN, Rupert JL (2008). "Keeping pace with ACE: are ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonists potential doping agents?". Sports Medicine. 38 (12): 1065–1079. doi:10.2165/00007256-200838120-00008. PMID 19026021. S2CID 7614657.

- ^ a b Montgomery HE, Clarkson P, Dollery CM, Prasad K, Losi MA, Hemingway H, et al. (August 1997). "Association of angiotensin-converting enzyme gene I/D polymorphism with change in left ventricular mass in response to physical training". Circulation. 96 (3): 741–747. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.96.3.741. PMID 9264477.

- ^ Sanders J, Montgomery H, Woods D (2001). "Kardiale Anpassung an Körperliches Training" [The cardiac response to physical training] (PDF). Deutsche Zeitschrift für Sportmednizin (in German). 52 (3): 86–92. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ^ Costa AM, Silva AJ, Garrido ND, Louro H, de Oliveira RJ, Breitenfeld L (August 2009). "Association between ACE D allele and elite short distance swimming". European Journal of Applied Physiology. 106 (6): 785–790. doi:10.1007/s00421-009-1080-z. hdl:10400.15/3565. PMID 19458960. S2CID 21167767.

- ^ Skeggs LT, Kahn JR, Shumway NP (March 1956). "The preparation and function of the hypertensin-converting enzyme". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 103 (3): 295–299. doi:10.1084/jem.103.3.295. PMC 2136590. PMID 13295487.

- ^ Kierszenbaum, Abraham L. (2007). Histology and cell biology: an introduction to pathology. Mosby Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-04527-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Niu T, Chen X, Xu X (2002). "Angiotensin converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion polymorphism and cardiovascular disease: therapeutic implications". Drugs. 62 (7): 977–993. doi:10.2165/00003495-200262070-00001. PMID 11985486. S2CID 46986772.

- Roĭtberg GE, Tikhonravov AV, Dorosh ZV (2004). "Rol' polimorfizma gena angiotenzinprevrashchaiushchego fermenta v razvitii metabolicheskogo sindroma" [Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme gene polymorphism in the development of metabolic syndrome]. Terapevticheskii Arkhiv (in Russian). 75 (12): 72–77. PMID 14959477.

- Vynohradova SV (2005). "[The role of angiotensin-converting enzyme gene I/D polymorphism in development of metabolic disorders in patients with cardiovascular pathology]". TSitologiia I Genetika. 39 (1): 63–70. PMID 16018179.

- König S, Luger TA, Scholzen TE (October 2006). "Monitoring neuropeptide-specific proteases: processing of the proopiomelanocortin peptides adrenocorticotropin and alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone in the skin". Experimental Dermatology. 15 (10): 751–761. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00472.x. PMID 16984256. S2CID 32034934.

- Sabbagh AS, Otrock ZK, Mahfoud ZR, Zaatari GS, Mahfouz RA (March 2007). "Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene polymorphism and allele frequencies in the Lebanese population: prevalence and review of the literature". Molecular Biology Reports. 34 (1): 47–52. doi:10.1007/s11033-006-9013-y. PMID 17103020. S2CID 9939390.

- Castellon R, Hamdi HK (2007). "Demystifying the ACE polymorphism: from genetics to biology". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 13 (12): 1191–1198. doi:10.2174/138161207780618902. PMID 17504229.

- Lazartigues E, Feng Y, Lavoie JL (2007). "The two fACEs of the tissue renin-angiotensin systems: implication in cardiovascular diseases". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 13 (12): 1231–1245. doi:10.2174/138161207780618911. PMID 17504232.

External links

[edit]- Proteopedia Angiotensin-converting_enzyme – the Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Structure in Interactive 3D

- Angiotensin+Converting+Enzyme at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Human ACE genome location and ACE gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.