Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital

| Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital | |

|---|---|

| Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust | |

Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital Main Building | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, England[1] |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | NHS England |

| Type | Specialist |

| Affiliated university | Imperial College London |

| Services | |

| Emergency department | No |

| Speciality | Maternity, obstetrics and neonatal care services |

| History | |

| Opened | 1739 |

| Links | |

| Website | www |

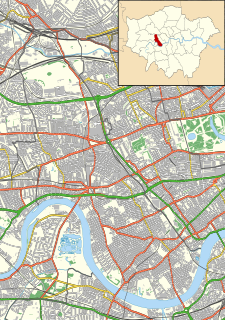

Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital is one of the oldest maternity hospitals in Europe, founded in 1739 in London. Until October 2000,[2] it occupied sites in Marylebone Road and at 339–351 Goldhawk Road, Hammersmith, but is now located between East Acton and White City, adjacent to the Hammersmith Hospital. It is managed by the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust.

History

[edit]

The hospital strictly dates its foundation to 1739 when Sir Richard Manningham established a maternity hospital of lying-in beds in a 17-room house on Jermyn Street.[3] This hospital was called the General Lying-in Hospital, and it was the first of its kind in Britain. In 1752 the hospital relocated from Jermyn Street to Marylebone Road and became one of the first teaching institutions.[4] The hospital appears to have arisen out of the 1739 foundation, but with varying degrees of recognition, developing over time.[5]: 1–18 On 10 January 1782 a licence was granted to the hospital charity by the Justices of the County of Middlesex (at that time a legal requirement for all maternity hospitals).[5]: 2

In 1809 the Duke of Sussex persuaded his mother, Queen Charlotte, to become patron of the hospital: it became, at that time, the Queen's Lying-in Hospital.[5]: 12 The queen held an annual ball to raise funds for the hospital. The medical centre moved to the Old Manor House at Lisson Green in Marylebone in 1813[5]: 20 where it was completely rebuilt to a design by Charles Hawkins in 1856.[5]: 28 Queen Victoria granted a Royal Charter to the hospital in 1885.[5]: 40 It was renamed Queen Charlotte's Maternity Hospital and Midwifery Training School in 1923.[6][7]

Maternal death was a common occurrence in London throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, especially among healthy young women who were in good health prior to their pregnancies.[8] For more than a century, the maternal death rate was used to measure the effectiveness of maternity services and treatment.[8] One specific cause of maternal death, postpartum infection (then known as childbed fever, and now also as puerperal sepsis), was referred to as the doctor's plague, because it was more common in hospitals than in home births. Once the method of transmission was understood in 1931, an isolation block was created in Goldhawk Road.[6] The rest of the maternity hospital moved to Goldhawk Road to co-locate with the isolation block in 1940.[6]

In 1948, following the creation of the National Health Service, the hospital linked up with the Chelsea Hospital for Women to form a combined teaching school.[6] The Chelsea Hospital for Women moved from Fulham Road to share the site under the new title Queen Charlotte's & Chelsea Hospital in 1988.[6] In 2000 the hospital moved to Du Cane Road, next to the Hammersmith Hospital.[6]

Notable Staff

[edit]- Alice Blomfield, (1866-1938)[9][10] Matron 1908–1924, had trained at The London Hospital under Eva Luckes, and previously worked at Queen Charlotte's as a sister in 1899, also as Matron of the East End Mother's Home in 1901, and of Addenbrooke's Hospital from 1905 to 1908. Whilst Matron of Queen Charlotte's the Out Patient's Department was extended,[11] she oversaw new accommodation for District Midwives,[12] and the first Preliminary Training School at a specialist hospital.[13] At the 1910 Nursing and Midwifery Conference and Exhibition, Blomfield gave a joint lecture on Infantile Blindness with Arthur Nimmo Walker,[14] a leading ophthalmologist from the St Paul's Eye Hospital, Liverpool.[15] In April 1913 she spoke at the Sixth Annual Nursing and Midwifery Conference about Preliminary Training Schools for Midwives.[16] She was active in the Incorporated Midwives' Institute, and was elected as a vice President in 1926.[17]

- Elsie Knocker M.M. (1884-1978) trained as a midwife at the hospital. She worked in the First World War as a nurse and ambulance driver.[18]

Facilities

[edit]

The hospital has a specialist "maternal medicine" unit for London, recognising that a need existed for specialist care to be offered to pregnant women who suffered from pre-existing medical conditions, or conditions that developed during pregnancy, whose treatment might impact upon the pregnancy. The unit is known as the de Swiet Obstetric Medicine Centre, and is currently housed in a small suite of rooms on the second floor of the Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital.[19]

The maternal medicine unit is separated into two distinct areas: a labour ward and a birth centre.[20] The delivery suites in the labour ward offer women a more traditional childbirth experience, while the birth centre strives to create a more "homely" environment.[20] The labour ward is a much larger unit with 18 labour rooms, conducting approximately 5,700 births between April 2016 and April 2017.[20] Women giving birth in this ward have access to epidurals during their birth. The birth centre is a smaller ward, with seven birthing rooms available for use. Approximately 1,030 births occurred in this centre between April 2017 and April 2018.[20] In the birth centre, the primary aim is conducting a natural birth that lacks medical aid. These births take place using birth pools and do not utilize epidural shots. Infants born in both the labour ward and birth centre have access to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).[20]

In addition to the birth center, Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital also offers a relatively new program called the "Jentle Midwifery" scheme.[21] This birth program ensures that the mother receives personalized, one-on-one care for the duration of her pregnancy, during labour, and up to four weeks after giving birth. Women who participate in this program receive care from the same midwife for the duration of their childbirth experience. The program is described as an alternative to the standard National Health Service (NHS) birthing options as well as private pay-for-treatment services.[21] In the program's first year, 74 women registered for the "Jentle Midwifery" scheme, bringing in over £160,000 for the hospital.[21]

Research

[edit]In 2016 the hospital partnered with Tommy's National Centre for Miscarriages, an organization that provides financial support for research on birth complications. This partnership established a miscarriage clinic at the hospital, which provides medical treatment for women who are participating in a research study related to miscarriages.[22] The goal of this initiative is to reduce the number of miscarriages by 50% by the year 2030 through better understanding of what causes miscarriages.[22] Tommy's created a pledge to research genetic causes of miscarriages, bacteria in miscarriages, and risk indicators of miscarriage during the first five years of the program.[23]

An additional 2016 initiative attempted to prevent cot death and reduce the infant mortality rate in the United Kingdom.[24] Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital sent 800 families home with foam mattresses inside of cardboard boxes for their newborn children. These boxes, popular in Finland, are designed to stop infants from rolling onto their stomachs, which induces sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).[24]

Today, Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital is the home of several ongoing research projects through the Imperial College Healthcare National Health Service (NHS) Trust.[25] The hospital is one of five teaching and research hospitals in London included in the Imperial Healthcare Trust. Research projects include essential tremor thalamotomy, Parkinson's dyskinesia pallidotomy, ablation of rectal and other pelvic cancers, uterine fibroid ablation, and drug delivery for oncology.[25]

COSMIC charity

[edit]COSMIC is an independent charity supporting the work of the neonatal and paediatric intensive care services of Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London. The charity funds a range of specialist equipment for the units, including patient monitoring systems and sensory play stations for those being treated on the wards.[26] COSMIC also funds an annual programme of training across units,[27] and provides emotional and practical support to families with babies and children in intensive care, as well as supporting research into childhood diseases such as studies Kawasaki Disease.[28]

Transport

[edit]The hospital is accessible by public transport; the nearest bus stops are "Wulfstan Street" and "Hammersmith Hospital"; the nearest tube station is East Acton (Central Line).[29]

Notable births at the hospital

[edit]- Alexander Aris, civil rights activist[30]

- Mischa Barton, actress[31]

- Sebastian Coe, athlete[32]

- Benedict Cumberbatch, actor[33]

- Roger Daltrey, musician.[34]

- Danny Kustow (1955-2019), pop musician[35]

- Dame Helen Mirren, actress (who in 1994 portrayed the hospital's namesake in The Madness of King George)[36]

- Daniel Radcliffe, actor[37]

- Zak Starkey, pop musician[38]

- Graeme K Talboys, author[39]

- Carol Thatcher, journalist[40]

- Mark Thatcher, businessman[40]

- Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury [41]

See also

[edit]- British Lying-In Hospital

- List of hospitals in England

- Portland Hospital

- Samaritan Hospital for Women

- South London Hospital for Women and Children

References

[edit]- ^ "Our hospitals". www.imperial.nhs.uk.

- ^ Google Earth imagery shows the site being demolished in September 2000.

- ^ "Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital". AIM25. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "History". Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Ryan, Thomas (1885). The History of Queen Charlotte's Hospital. London, UK: Hutchings and Crowsley, Limited. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Queen Charlotte's Maternity Hospital". Lost hospitals of London. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "The National Archives | Search the archives | Hospital Records| Details". www.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ a b Chamberlain, Geoffrey (1 November 2006). "British maternal mortality in the 19th and early 20th centuries". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 99 (11): 559–563. doi:10.1177/014107680609901113. ISSN 0141-0768. PMC 1633559. PMID 17082299.

- ^ Alice Blomfield, Birth Certificate, 5 February 1866, Barton, Luton, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire; General Register Office for England and Wales

- ^ Alice Blomfield, Grant of Probate, died 16 June 1938, Probate granted 11 July 1938; Probate Search Service [Available at: https://probatesearch.service.gov.uk ]

- ^ Anonymous (21 April 1917). "Queen Charlotte's Hospital; The Ante-Natal Department". The Nursing Record. 58 (1516): 286 – via GALE PRIMARY SOURCES, Women's Studies Archive.

- ^ Anonymous (1 July 1916). "Post Graduate Week". The Nursing Record. 57 (1474): 18 – via GALE PRIMARY SOURCES, Women's Studies Archive.

- ^ Anonymous (24 August 1912). "Queen Charlotte's Hospital - Preliminary Training School". The Nursing Record. 49 (1273): 163 – via GALE PRIMARY SOURCES, Women's Studies Archive.

- ^ "Like Father Like Son". Liverpool University Hospitals. 15 February 2019. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Anonymous (1 May 1910). "Nursing and Midwifery Conference and Exhibition - Programme of Conference". Nursing Notes. 23 (269): 114 – via GALE PRIMARY SOURCES, Women's Studies Archive.

- ^ Anonymous (1 May 1913). "Midwifery Conference". Nursing Notes. 26 (305): 132 – via GALE PRIMARY SOURCES, Women's Studies Archive.

- ^ Anonymous (6 February 1926). "Incorporated Midwives' Institute". The Nursing Times. 22 (1084): 132 – via GALE PRIMARY SOURCES, Women's Studies Archive.

- ^ Hallett, Christine E. (2016). Nurse writers of the Great War. Nursing history and humanities. Manchester [UK]: Manchester University Press. pp. 144–146. ISBN 978-1-78499-252-1. OCLC 920729989.

- ^ Maternal medicine Archived 3 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d e "The Delivery Suite, Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital - Which?". Which? Birth Choice. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Atkins, Lucy (19 January 2006). "What price for a perfect delivery?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ a b "First National Miscarriage Research Centre opens at Imperial | Imperial News | Imperial College London". Imperial News. 26 April 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ "National Centre for Miscarriage Research officially opens". www.birmingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Hospitals in England are adopting one of Finland's best ideas". The Independent. 30 June 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Research Site Profile: Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust - Focused Ultrasound Foundation". www.fusfoundation.org. 14 March 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ cosmic. "Equipment". COSMIC. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ cosmic. "Training". COSMIC. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ cosmic. "Research". COSMIC. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ "Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital". Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ Wintle, Justin (18 March 2008). Perfect Hostage: A Life of Aung San Suu Kyi, Burma's Prisoner of Conscience. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-62636-754-8.

- ^ "Hellomagazine.com". Hellomagazine.com. 24 January 1986. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ "Coe, Sebastian (Part 1 of 4). An Oral History of British Athletics - Sport - Oral history | British Library". Sounds. 29 September 1956. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Culbertson, Alix (5 November 2014). "Kensington heartthrob Benedict Cumberbatch gets engaged to Hammersmith girlfriend". Ealing Gazette. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ Neill, Andy; Kent, Matt (26 August 2011). Anyway Anyhow Anywhere: The Complete Chronicle of the Who 1958–1978. Ebury Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7535-4797-7. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ "Birth announcement for Danny Kustow, 'Births, Marriages & Deaths'" (PDF). British Medical Journal. 21 May 1955. p. 1293.

- ^ "'Whenever I see the Queen, I think, "Oh ... there I am"': The right royal progress of Helen Mirren". The Independent. 20 January 2017.

- ^ Blackhall, Sue (2014). Daniel Radcliffe - The Biography. John Blake Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 9781784182410.

- ^ "Zak Starkey". Truth About the Beatles' Girls. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "FreeBMD Entry Info". www.freebmd.org.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ a b Campbell, John (5 January 2012). The Iron Lady: Margaret Thatcher: From Grocer's Daughter to Iron Lady. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4481-3067-2.

- ^ Atherstone, Andrew (28 August 2013). Archbishop Justin Welby: The Road to Canterbury. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 978-0-232-53034-6.

Sources

[edit]- Ryan, Thomas (1885). The History of Queen Charlotte's Lying-in Hospital from its foundation in 1752 to the present time, with an account of its objects and present state. Hutchings & Crowsley.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital at Wikimedia Commons

- 1739 establishments in England

- NHS hospitals in London

- Maternity hospitals in the United Kingdom

- Hospital buildings completed in 1946

- Hospital buildings completed in 1988

- Hospital buildings completed in 2001

- Hospitals established in 1739

- Buildings and structures in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham

- Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

- Voluntary hospitals

- Women in London

- Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz