Robert J. T. Joy

Robert J. T. Joy | |

|---|---|

Colonel Robert J. T. Joy, Medical Corps, US Army | |

| Nickname(s) | Bob |

| Born | April 5, 1929 Narragansett Village, Rhode Island |

| Died | April 30, 2019 (aged 90) Washington, District of Columbia |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1954–1981 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | United States Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, Natick, Massachusetts

United States Army Medical Research Team (WRAIR) |

| Battles / wars | Vietnam Defense Campaign Vietnam Counteroffensive Phase II |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Medal Army Commendation Medal |

| Other work | Professor and Chair, Section of Medical History, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences |

| Signature |  |

Robert J. T. Joy (April 5, 1929 – April 30, 2019) was an American physician and career Army Medical Corps officer who was an internationally recognized scholar in the field of the history of medicine. He was also a key leader in U.S. Department of Defense Medical Research and Development, and served as one of the key founding staff members of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, where he served as the first commandant of students, chair of the department of military medicine, and, after his retirement from military service, first professor and chair of the section of medical history at the university.

Education, early years, and family

[edit]Robert John Thomas Joy was born in Narragansett Village, Rhode Island, the only child of Angelo Francois Joy, an Italian immigrant hotelier, and his Narragansett-born wife Mary F. (Egan) Joy.[1] His mother Mary was a first-generation American born of Irish Immigrant parents,[2] and Joy described his upbringing as "lace curtain Irish." His primary and secondary education moved between Narragansett in the spring and St. Petersburg, Florida in the fall as his family moved between their hotels with the tourist trade.[3]

After completing High School, Joy enrolled in the Rhode Island State College, receiving a Bachelors of Science with a dual major in pre-medicine and pre-law in 1950.

Joy then attended the Yale School of Medicine while participating in an Army Reserve Officers Training Corps Medical Corps scholarship—in the 1950s the Army had such programs—and completed his medical training in 1954.

It was at Yale that his life-long love of the history of medicine—and his association with the American Association for the History of Medicine began. He and a classmate restarted the Nathan Smith Club, the school's student History of Medicine Club, which had lain dormant for several years. The club met monthly at a faculty member's home, a student would present a paper, and other members would critique the paper. Joy volunteered to present the first paper when the club re-launched, and his paper would eventually be published and awarded the Association's Osler Medal for the "best unpublished essay on a medical historical topic written by a student enrolled in a school of medicine or osteopathy in the United States or Canada."[4][5][6]

Joy was married twice. His first marriage ended in divorce and produced two children, a son and a daughter. His second wife preceded him in death by about 1 year.

Career

[edit]Internship, residency, and early assignments

[edit]Joy was awarded a reserve commission in the Medical Corps upon his graduation in June 1954, and was ordered to active duty in the Army of the United States later that month to complete an internship at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, District of Columbia. Joy later commented that while he had been offered the choice of deferring his active duty service obligation until after he had completed a civilian internship, attending an Army internship at Walter Reed made much sense to him, not only because of the quality of the training that Walter Reed would afford him, but because a First Lieutenant in the Medical Corps was paid about $250 a month, while a standard civilian intern's salary in those days was about $50 a month, and he had a wife and young child to support.[7]

After completing his internship, Joy was commissioned in the Regular Army and transferred to the Army Medical Service School at Fort Sam Houston, Texas for completion of the Army Medical Department Officer Advanced Course.[8] Joy would later remember the course as six months of instruction on the proper way to apply wax to hospital floors and fill out utterly meaningless paperwork—and that he was called before the Commandant of the School for allegedly serving as the ringleader of a group of Medical Corps officers who had shelled the Garrison Commander's quarters with golf balls one night using the post's salute cannon.[citation needed]

Following the Advanced Course Joy was sent to serve as the Battalion Surgeon of the 714th Tank Battalion, stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia. As the battalion surgeon Joy served as a staff officer to the battalion commander, but he also served as the battalion's medical platoon leader at the same time, and led his platoon as the battalion engaged in a series of maneuvers at Fort Polk, Louisiana in preparation for rotation to Germany in 1956 as part of Operation Gyroscope, where the battalion would become part of the 4th Armored Group—without Joy, who by that time had moved on to his residency training in internal medicine at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.[9]

In the summer of 1956, Joy returned to the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, where he spent the next two years completing a residency in internal medicine, followed by a year-long fellowship program in medical research at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. It was during his fellowship at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research that Joy met Jay P. Sanford, another young Army doctor, a draftee who was serving out his commitment under the Berry Plan. Joy and Sanford would remain professional colleagues and friends for the rest of their lives.[10]

United States Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine

[edit]Following completion of his residency, Joy and his family moved to Fort Knox, where he was assigned to the newly constructed hospital on post, where he would practice medicine in the cardiology service while simultaneously serving as the assistant director, and later director, of the Environmental Division of the U.S. Army Medical Research Laboratory at Fort Knox. He would serve in that position for two years, until the laboratory was reorganized, shifting its focus towards blood transfusion, biophysics, and psychophysiology. The U.S. Army Medical Research Laboratory at Fort Knox had originally been established as the Armored Medical Research Laboratory in the early 1940s, and had focused its research since that time on the physiological effects of armored vehicles on their crews.[11][12]

In 1961, the environmental division of the Army Medical Research Lab at Fort Knox was moved to Natick, Massachusetts, redesignated as the United States Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, and collocated with the Quartermaster Research and Engineering Command. [13] Because portions of the Quartermaster Center were being incorporated into the new lab, and because the Quartermaster Center's Commanding General would remain in the laboratory director's rating chain, the Medical Department had difficulty finding a senior officer willing to assume command. Joy, still only a Captain, volunteered to command the lab and, appointed to command "at the direction of the President" in accordance with then-current command policies to exercise command over officers senior in date of rank to him, moved to Natick and assumed command of the new lab when it was activated on 1 July 1961.[14]

After a year in command without apparent harm to his career, Captain Joy was replaced as commander by Lieutenant Colonel William H. Hall, MC, who would command the lab from 1962-1965. Joy assumed the position Research Internist until 1963, when he began a period of government funded civilian training at Harvard University, being awarded a Master of Arts in Physiology in 1965. He had curtailed his education in order to assume a position as the commander of the U. S. Army Medical Research Team (WRAIR) in the Republic of Vietnam.[15]

United States Army Medical Research Team, Vietnam

[edit]

In July 1962, shortly after the first U.S. Army medical units were deployed to Vietnam, the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research deployed a small survey team to evaluate available resources for conducting medical research and plan for necessary expansion. That team recommended that existing medical research programs be expanded to include a research team from WRAIR, to be located in Saigon, similar to teams already operating in Bangkok and Kuala Lumpur which would conduct studies of U.S. personnel and local national troops and civilian populations.[16]

The U. S. Army Research Team (WRAIR), Vietnam was established in November 1963 with seven officers and 12 enlisted, under the command of then-Lieutenant Colonel Paul E. Teschan, MC, USA. With the established 12-month rotation cycle, Joy, now a Major, rotated to Vietnam as the third commander of the research team, replacing Lieutenant Colonel Stefano Vivona, MC, USA.[17]

Joy's tour as commander of the medical research team coincided with the initial buildup of U.S. combat forces, with the concomitant increase in exposure to tropical diseases by U.S. forces, primarily malaria, and it was in this area that much of the team's effort was focused during Joy's tenure in command. As data indicated a potential rise in the number of cases of chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria, and the team focused their efforts in this area. One of their discoveries was "asymptomatic malaria," which was a possible threat to the continental United States, as it could be imported by redeploying service members. They also documented failures in malaria prophylaxis discipline and use of personal protective measures, which helped provide information to improve malaria control, and the introduction of new drugs for malaria control, including Fanasil and pyrimethamine.[18]

Another major contribution to the control of malaria in Vietnam was the introduction of diaminodiphenylsulfone (DDS). The efficacy of this drug as a prophylactic agent was confirmed in volunteers in the United States, and in 1966, a field test in Vietnam proved its value in combat troops. Subsequently, it was routinely used by military personnel in Vietnam for prophylaxis against falciparum malaria.[19]

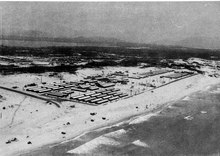

The team also recommended that a central rehabilitation facility for malaria patients be added to the troop list and simultaneously be used as a facility for studying the disease and treatment regimes for it. The Army Surgeon General approved the recommendation and added the 6th Convalescent Center to the deployment list.[20] The Center was activated on 29 November 1965 at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, arrived in Vietnam on 16 March 1966 and was inactivated at Cam Ranh Bay on 30 October 1971 when its staff was used to resource the U. S. Army Drug Rehabilitation Centers at Cam Ranh Bay and Long Binh.[21]

Under Joy's leadership, the team also conducted extensive research into neuroendocrine stress caused by combat, in helicopter crewmen and Special Forces "A" Detachment members, contributed significantly to the understanding of the pathophysiology of stress in the soldier. Studies of heat stress incurred by crews of the Mohawk (OV-1) aircraft led to changes in clothing and to ventilation of the cockpit, measures which materially improved crew comfort and efficiency. Collaborative studies with the Department of Neuropsychiatry of the ARVN Cong Hoa Hospital led to a better understanding of the stresses of combat affecting both American and Vietnamese soldiers. It was this research that led to Joy's receipt of the Air Medal, as well as linking into his previous research into environmental medicine.[22]

In later years, Joy would use his experiences as the "nameless staff consultant in malaria" in his lectures on the commander's role in maintain the health of the command, comparing his experience in Vietnam with that of Field Marshall William Slim in Burma. He would compare malaria rates in the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) against that of Slim's Army, and then quote Slim's command philosophy from his book Defeat into Victory: "You doctors think you can cure malaria, but you can't. I can and I'm going to."[23]

At the end of his tour, Legion of Merit in hand, Joy returned to the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Environmental Medicine. Shortly after his return, the U.S. Army Medical Research Team (WRAIR), Vietnam would be awarded the Meritorious Unit Commendation, the achievement that Joy would be most proud of during his deployment, as it recognized the performance of all the members of his team.[24]

United States Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine

[edit]Following the completion of his tour in Vietnam, Joy returned to the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, serving during this tour as Deputy Director for Field Research. During the year he would serve in this position, his major challenge would be to lead a field team to Greenland to conduct a study on winter survival gear before departing for the Armed Forces Staff College. It was also during this assignment that Joy attended Army Flight Surgeon School.[25]

Ever the Military Medical Historian, at the request of the Institute's Director, Joy prepared an extended annotated "Reading List in Military History and Military Medicine," which the director distributed to the staff in May 1967. Far ranging, covering topics from general military history including Slim's Defeat into Victory, Huntington's The Soldier and the State and T. R. Fehrenbach's This Kind of War to operational history—all works of S. L. A. Marshall—to works on warfare in the arctic, the desert, and, of course, the jungle and counter-insurgency, including John Masters' The Road Past Mandalay.[26]

The Armed Forces Staff College

[edit]During the 1967-1968 school year, Joy attended the Armed Forces Staff College in Norfolk, Virginia. The Armed Forces Staff College, established in 1946, provided joint service education to the officers and civilians who attended it, developing a cadre of officers who could support the Secretary of Defense and the Joint Staff. Although it was far from the Joint training mandated by the Goldwater-Nichols Act reforms, it was the only show in town—and it granted credit for attendance at a Command and General Staff College to officers who attended it.[27]

As head of the U.S. Army Medical Research Team (WRIAR) in Vietnam, Joy worked closely with in-country counterparts in the Navy, Air Force, and the United States Public Health Service, which staffed the United States Operational Mission for the Department of State, as well as the Vietnamese Ministry of Health. In Vietnam he observed Joint operations as they were conducted in the 1960s, but didn't see "jointness" in the medical departments of the services.[28]

The year at Norfolk also gave Joy to further reflect on the future of military medicine—and continue his studies in military medical history—and it was at the College that he began to develop a much more structured view of military medicine in a Joint environment. Military Medicine not as service stove-piped systems on a multi-service battlefield, but a true joint medical system.[29]

Defense Medical Research Leadership

[edit]After completing the Armed Forces Staff College, Joy was assigned to the Medical Research Division of the Office of the Army Surgeon General, where he would serve for the next 18 months.[30] This was a time of great import for the research enterprise in the AMEDD, where a major portion of the Departments $51.4 million research program was devoted to solving specific problems relevant to ongoing operations in the Republic of Vietnam. It was also a period that saw the Medical Unit, Self-contained, Transportable (MUST) hospital equipment set, originally approved for use in Vietnam, certified for worldwide deployment in the full range of operational environments, and the approval of a major research and development construction program which would have consolidated Army Medical R&D facilities from 13 sites to six, while increasing the Army's in-house medical research capability by some 40%.[31][32]

Joy then moved to his first true "Joint" position, as Deputy for Medical and Life Sciences, Office of the Director of Defense Research and Engineering—now the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering—where he would qualify for the Office of the Secretary of Defense Identification Badge, a rare award for Medical Corps officers; rarer still for officers who served outside of the office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Health Affairs). Although little is known of Joy's specific activities in the office, his period there has been recognized as one of the most successful in the history of Defense procurement, and he undoubtedly took lessons on research, procurement, and jointness with him to the remainder of his assignments.[33]

The Walter Reed Army Institute of Research

[edit]

In 1973, Joy would be assigned to the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research as the Institute's Deputy Director and Deputy Commandant while Colonel Edward Buescher served as Director and Commandant. The mid 1970s was a tough time for the Army Medical Research and Development community as funds were sparse and inflation high in the post-Vietnam Army and racial tensions and drug abuse problems high. Joy and Buescher formed an ideal team, with Buescher focusing "up and out" while Joy focused "down and in." The Buescher and Joy command team was forced to conduct a Reduction in Force at WRAIR but placed every person displaced before the effective date of the reduction in force.

Joy worked tirelessly to establish the best race relations in the AMEDD, talking with people and walking the halls of the laboratory to make sure equality was enforced as well as discussed. A team from WRAIR provided guidance and inspiration to help the Walter Reed Army Medical Center with its difficult problems when racial tensions in the hospital boiled over. It was also the time for transition from WRAIR as the inspirational research leader and semi-autonomous lab to the real Medical Research and Development Command with surgical research in San Antonio, nursing research moved to the hospitals as inherently clinical, and human performance work and weapons threat research in other labs. WRAIR would focus on Infectious Diseases and Neuropsychiatry gong forward—the greatest cause of man-days lost to the soldier.[34]

In 1975, upon the departure of Buescher, Joy advanced to the position of director and commandant of WRAIR. The Army Surgeon General, Lieutenant General Richard R. Taylor had described the Director's position as Joy's "dream job"—and so it should have been for any Army medical researcher—command of the Army's largest and oldest medical research facility, long associated with the giants of Army medical research, including George Miller Sternberg, Carl Rogers Darnall, Edward Bright Vedder, and Major Walter Reed himself. For Joy, a student of military medical history, it was, indeed, a dream job.[35]

It was during Joy's tenure as deputy director and director that WRAIR saw its overseas laboratory footprint greatly expanded, with WRAIR assuming control of the overseas medical research units in Malaysia and Panama, as well as the Army's portion of the lab in Bangkok. An additional lab was established in 1973 in Brasília as part of a cooperative agreement between WRAIR and the University of Brasília, and the U.S. Army Medial Research Unit—Belém was established in Belém, Brazil to investigate disease transmission along the new Trans-Amazon highway.[36]

Robert J. T. Joy and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

[edit]Establishing the University

[edit]When Joy first began to hear the details of the new DoD medical school, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, from his perch at WRAIR, he greeted the idea with skepticism. He questioned the need for the school, and the ability of the Department of Defense to successfully execute the concept. He felt that most of the expertise lay in the Army and the Navy, not at the Department level.[37]

But then Joy's longtime friend and associate Jay P. Sanford, newly appointed dean of the school of medicine, came calling on Joy, soliciting his ideas on how to bring the school to a successful fruition. By some accounts their initial meeting was over beer in a bar in Silver Spring, where they talked long into the night, sketching out the concept for the school on a bar napkin.[38][39] By other accounts, they began their meeting at the university's temporary headquarters over a CVS Pharmacy in Bethesda, Maryland, then adjourned to Joy's house, working late into the evening. In either event, they quickly developed a straw-man concept which they then fleshed out sufficiently to obtain the blessing of the board of regents and began to move forward with plans for the university.[40]

It was during this process that Joy, who had been contemplating retirement and been making quiet inquiries regarding post-service employment, approached Sanford about the position of the Professor of "Military, Naval, or Air Science" called for in the university's enabling legislation. Joy had realized that, rather than retiring, he desired to continuing service—on the faculty of the university. Sanford agreed, Joy prepared a nomination packet and submitted it through the Army Surgeon General, and was quickly approved by the Board of Regents. He and Sanford then began working of fleshing out the rest of the curriculum, focusing particularly on the military portion of the curriculum. Rather than having a Professor of Military Science, they decided instead to create a Department of Military Medicine, with Joy as the chairman.[41]

The new department would focus on those uniquely military portions of the curriculum. But only those truly unique aspects of the military environment. So while the Department of Military Medicine might cover the operational aspects of operating on a chemically or radiologically contaminated battlefield, for example, the effects of chemical agents at the cellular level would be taught in biochemistry, right alongside the Krebs cycle, or the effects of an arid or tropical environment on the body would be taught in human physiology. In this way, the school would integrate the military-unique aspects of the curriculum throughout the university, rather than adding it on as a separate topic, much as ROTC would have been in a civilian institution's undergraduate program.[42]

Joy also realized, as he developed his portion of the curriculum, that the University required a military commander for the students—responsible for their day to day discipline, as well as ensuring that the administrative minutia that required a commander's signature could be completed in a timely manner. Joy approached Sanford with the recommendation that he—Joy—should logically hold the position as the senior uniformed officer assigned to the institution. He further argued that the position should be titled "Commandant," a term traditionally associated with military schools. Sanford quickly agreed, presented the concept to the Board of Regents, and obtained their approval. Joy could then begin recruiting a staff for the new department.[43]

The First Classes

[edit]

As the first students reported for classes at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology on the campus of the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, which the University was using for classroom and laboratory space, Joy was still recruiting his faculty and staff. This included LTC John F. Erskine, MSC, USA as deputy commandant and associate professor in 1978 and Capt Ann Marie Pease, USAF, MSC and LCDR Anthony R. Arnold, MSC, USN as assistant commandants and assistant professors in 1978 and 1979, respectively. By having an officer from each of the services assigned, they would be better able to deal with students' service unique issues as they might crop up.[44] Joy set expectations with each arriving class as he oriented them to the Campus,, reviewed policies covering attendance, personal and professional behavior, and other requirements associated with military life. As the first class was predominately military—and small—it served as a learning tool, and adaptations were made with subsequent classes as they increased in size. Beginning with the second class, non-prior service students attended branch orientation courses prior to arriving at the university. The Commandant's Office also became responsible for those activities which were important to life as an officer—physical training, sporting events, Dining-ins and Dining-outs, publication of a student newspaper and yearbook, training and selection for students wishing to attend Airborne or Air Assault training and, beginning in 1978, Expert Field Medical Badge testing for all interested students, regardless of service. Additionally in 1978 Joy, in his role of Commandant, began quarterly inspections of the MS-1 and MS-II students for proper wear and care of their uniforms, as well as personal grooming.[45]

Realizing that much of the art of military medicine was understanding the military as much, or more, than understanding medicine, Joy used his connections on the Joint Staff and in the Offices of the Secretary of Defense and elsewhere in the greater DC area to bring in guest speakers to lecture the students on military topics. Joy would hold these lectures at 1400-1600 on Fridays, but would notoriously run long in those early days and would often end up moving to the Officers Club afterwards, where the students could further interact with the guest speakers. Although a bit rough at first, with the inaugural class nicknaming themselves the "Charter Martyrs," by the time Joy stepped down as chair of the department of military medicine and history in 1981 the training was well synchronized and coordinated.[46]

As the inaugural class began attending courses Joy, assisted by the University's fist Assistant Dean of Students, Army Medical Corps Lieutenant Colonel (and future Army Surgeon General) Ronald R. Blanck worked to ensure that the instructors met the quality that they expected. Joy and Blanck, along with other senior leaders in the University realized that with the end of Selective Service—and with it the Doctor Draft—in 1973, the Armed Forces would become increasingly reliant on women to fill the ranks of the Medical Corps, and they expected their instructors to reflect a welcoming environment. No more would locker room humor, course talk, or inappropriate slides be allowed. With the first class over 10% female, the second class about 20% female, and later classes approaching 1/3 female, this was an important early framework for the university, and one both men took to heart, each being the father of daughters themselves.[47]

Joy was also challenged with developing summer experiences for his MS-I and MS-II students. Unlike civilian medical students, who had their summers off, the university's students were active duty military officers, entitled to only 30 days a year of leave. This meant that Joy had to develop summer experiences for his students between their first and second years to fill about six weeks of time constructively. It was during these summer periods that the students would join their services in the field. Some students would attend Airborne or Air Assault training (like the EFMB, not limited by service); Air Force and Naval students interested in flight medicine could conduct altitude certification training at Andrews Air Force Base. Other students might, depending on their service, go to sea with a naval ship on a short shakedown cruise, go to an army division and serve as an assistant battalion surgeon, or work in an air force hospital for three weeks, followed by three weeks shadowing an Air Force flight surgeon. At the end of their summer experience, they would be allowed to take two weeks of leave before beginning their second year of studies.[48]

And then, of course, came the history courses—some 33 hours of lecture in the MS-I curriculum.[49] Joy used the history course to provide a common linkage for the students. To show them how what they were doing tied into what had come before them, and the role that physicians played in society, and in history. He built on the common military medical heritage that they shared, and how what they did was influenced by those that went before them—from Dominique Jean Larrey and Jonathan Letterman to James Lind, Malcolm Grow, Louis Pasteur, Luther Terry, Walter Reed, and Carlos Finlay. In addition to attending lectures, each student had to prepare a history paper on a subject mutually agreed upon by the student and Joy, which led to their letter grade in the course—and built a small cottage industry of avocational military medical historians as well among those students who gained an interest in the subject.[50] At first he relied on others, including guest speakers and other faculty members with a penchant for storytelling, but by the time the inaugural class graduated, Joy owned the history program—and with that ownership came speaking engagements, both locally, in the United States, and abroad. Military Medical History now had a face, and that face Robert J. T. Joy's. And through it all, of course, he continued to tell the story of a nameless young malaria researcher in Vietnam who, despite his ability to quote Sir William Slim of Burma, was unable to influence senior commanders in the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam to implement proper malaria control regimes.[51]

The Section of Medical History

[edit]

After the graduation of the inaugural class of medical students in 1980, Joy informed Sanford of his intent to retire from military service. At Sanford's request, Joy agreed to remain for an additional year, to allow for an orderly search for a replacement. Additionally, Sanford wanted to make some organizational changes in the University. With the approval of the University's Board of Regents, he reorganized the Department of Military Medicine and History and the Section of Operational and Emergency Medicine into a Department of Military and Emergency Medicine and a separate Section of Medical History, and separated the duties of the Commandant from those of the Chair of Military Medicine.[52]

When Joy again announced his intent to retire, this time in March 1981, Sanford offered Joy the position of chair of the Section of Medical History—subject to a national search and approval of the board of regents—and Joy agreed, subject to his ability to hire a tenure track assistant professor. Sanford agreed, a search committee was formed, and when Joy retired on November 1, 1981 he was appointed professor and chair of the Section of Medical History.[53] Joy then organized a national search for an assistant professor of medical history, gathering resumes and holding final interviews at the 1982 annual meeting of the American Association for the History of Medicine, hosted that year by the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. After completing panel interviews at the meeting, Joy selected Dr. Dale C. Smith, PhD, a recent graduate from the History of Medicine program at the University of Minnesota as the new assistant professor in the Section of Medical History.[54] Smith joined the section in July 1982, joining Joy and Dr. Peter Olch, MD, a retired United States Public Health Service Captain who had recently retired as the Deputy Director of the History of Medicine Division of the National Library of Medicine who had joined the section as an adjunct associate professor.[55]

With the expanded faculty, the section could begin to take on additional workload—and did. From 1982 to 1987, Joy served as the editor of the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, while Smith served as associate editor. It was also in 1982 that the USUHS started its first Master of Public Health Class, and Smith prepared and taught a 36-hour course in that program. From 1994 to 1998, Joy and Smith also taught a 24-hour series of lectures on the history of medical research to the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research Fellowship in Medical Research—the same fellowship program where Joy and Sanford originally met in the 1950s. Commitments to lecture in other teaching programs in the National Capitol Region soon followed.[56]

Invitations for speaking engagements continued to come to the section, and increased—as did travel. Invited lectures for all three members of the faculty increased, both in the United States and abroad as the section's reputation as a center of expertise in the unique specialty of military medical history became more widely known.[57] Over time, Joy decreased the lectures he gave in the MS-I course, while Smith and Olch developed their own as replacements. Additionally, the faculty participated in committees of associational and institutional government, serving on National Institutes of Health study sections, the editorial boards of several journals, council and executive board memberships, society officers, and USUHS committees.[58]

In 1986, the Section of Medical History hosted the annual meetings of both the American Military Institute and the US Air Force History Association. Both had asked to have military medical themed speaker topics and themes for their conferences, which the section provided.[59] By 1995, after 14 years as chair and twenty years with the university, Joy announced his intent to step down and enter emeritus status, officially ending his working career.[60]

The Army Fellowship in Military Medical History

[edit]In 1984 Colonel Thomas Munley, Chief of the Academy of Health Science's Military Science Division, which was responsible for the Army Medical Department's Officer Basic and Advanced Courses, approached Joy and asked if it would be possible to establish a training program to produce a qualified military medical history instructor for the academy, to increase the amount and quality of history presented in the Officer Basic and Advanced Courses.[61]

Established as a postgraduate fellowship rather than a formal degree granting program, the Fellowship in Military Medical History allowed Army Medical Service Corps officers in the rank of captain or major to apply as part of the Army Medical Department's formal schooling program. They would then be screened for suitability as an instructor by the Military Science Division, and satisfactory candidates would be sent to the Section of Medical History for final selection by Joy and Smith. Funding for the program, almost exclusively for the cost of temporary duty travel to conferences, was funded by the Academy of Health Sciences.[62]

Once assigned to the Fellowship Program, which involved a permanent change of station move, the student entered a directed reading program described by Joy as "a book a day." The goal of the program was to develop an officer with a strong background in the history of medicine, in general military history, and in military medical history, and in particular those things which have had a strong influence on how medicine in the United States—and in particular the United States Army reached its current state. This was no history and heritage training course, but a graduate level program in the history of military medicine, taught in the Socratic Method, with the student preparing lectures to present to Joy, Smith, or other faculty members.[63]

In addition to the formal education, the Fellows attended the annual meeting of the American Association for the History of Medicine and the Society for Military History (still named the American Military Institute in the early years of the fellowship). They also attended seminars at the Johns Hopkins University Institute for the History of Medicine and other local DC groups, such as the monthly "Military Classics Seminar." They visited the United States Army Center of Military History and the Military History Institute at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. And from the fourth fellow onward, they attended the TRADOC Military History Instructor Course in route to the fellowship. All of these additional experiences served to provide a well rounded historian—prepared to be an operational historian, and not just an instructor for the Academy of Health Sciences.[64]

In 1994 the Fellowship was converted to a formal Masters producing program, and its length was expanded to 15 months. To ensure that the Fellows—now Masters students, but still referred to by that term by their fellow alumni—received proper training in historiography and other areas, the students took several classes at American University to round out their training. Between 1984, when the first Fellow was admitted, and 2010, when the last Masters student graduated (although the program remains on the books), the program produced 7 Fellows and 5 Masters recipients. Of those, three published peer reviewed papers during their fellowships, one won first place in the Annual U.S. Army Center of Military History writing contest, and one won the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States History Paper competition.[65][66][67]

The production of trained historians provided one benefit that was unanticipated at the time the program was created, and that was the ability to deploy medical historians to an active theater of operations. During the Vietnam War, the 44th Medical Brigade, the Army's senior medical command and control headquarters in country, had the 27th Military History Detachment, commanded by a Medical Service Corps officer, embedded in its headquarters for most of its deployment, where it collected documents, prepared historical reports, and supervised the historical activities of the command. The Army Medical Department had lost that capability in the ensuing years, and the fellows returned it to the Department. Operation Desert Storm saw two fellows deployed—one with the Center for Army Lessons Learned collection team, and a second as the theater medical historian, who collected oral history interviews, sent them to the Center for Military History, collected artifacts for the Army Medical Department Museum, and prepared the Command Historical Report for the 3rd Medical Command (Provisional). Since Desert Storm, USUHS History Fellows continued to deploy in the role of operational historians until the last of them left active duty, with the majority of them having served overseas as medical historians.[68]

Joy's later years

[edit]Joy had originally planned to retire and assume an emeritus status in 1995, remaining an additional year in order to see the transition of the Fellowship in Military Medical History into a Master of Military Medical History. Having completed that, he formally retired from the university in the summer of 1996.[69] In a rare show of respect to Joy's role in the creation of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, he was chosen as the commencement speaker for the 1996 graduation of the school, and was awarded that year's Outstanding Civilian Educator Award.[70] By contrast, the 1995 commencement speaker was Dr. Richard C. Reynolds, M.D., the Executive Vice President of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the 1997 commencement speaker was Dr. C. Everett Koop, M.D., Sc.D., former Surgeon General of the United States. [71][72]

Once Joy stepped down as professor and chair of the department of medical history, Dr. Dale C. Smith, PhD, was appointed interim chair of the department. After nearly a year Smith, who had been with the department since its inception and was Joy's preferred choice for the position, was selected as the new professor and chair of the department of medical history.[73]

Joy continued to teach, with Smith and a newly hired assistant professor picking up more of the course load, and Joy shedding his, until he was eventually four lectures per year to the freshman medical students. He also began reducing the amount of travelling he performed to present lectures, deferring to the staff of the Department of Medical History or to other medical historians he knew who might present on the topic. Finally, in 2005, wishing to leave the lecture platform before he had passed his prime, Joy elected to give his last scheduled lecture at the University. Delivered on 5 April 2005, in addition to the freshman medical student class, many of Joy's friends and former faculty attended as well, including six of his Military Medical History Fellows—more than half of the program's output to that point.[74]

Joy continued to visit the departmental offices, lectures or no, continued to give the occasional lecture on the road, and attend the annual conferences of the Society for Military History and the American Association for the History of Medicine until age and health precluded him from doing so. He then entered a quiet retirement with his wife Janet until her death, again enjoying the world of the pulp science fiction magazines he had enjoyed in his youth and long collected as a hobby until his death, at the age of 90, on 30 April 2019.

In a 2010 interview for a Yale Medicine Magazine article on medicine and the military, Joy stated that, as he reflected on his long career, what he enjoyed most was tutoring, advising, and encouraging young men and women. And that, following that, what he most enjoyed was command. Even at age 81, 14 years after entering Emeritus status on the university faculty, he still visited the office one day per week.[75]

Robert J. T. Joy's Role in the Study of the History of Medicine

[edit]Joy's entire adult life was, in one way or another, associated with the history of medicine—from the time he was awarded the American Association for the History of Medicine's William Osler Medal as a first year medical student in 1954 until he was awarded the Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012. In between he was acknowledged for his assistance in over 100 books, delivered over 80 named lectures, and was a visiting professor on four continents. His resume included author or co-authorship of more than 140 papers or chapters.[76]

Joy also spent many years as a journal editor, serving as a student editor of the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences in 1953-1954, as associate editor from 1977-1980, and as editor from 1983-1987. He also served on the editorial advisory board of the American Association for the History of Medicine's Bulletin of the History of Medicine from 1993-1996.

Joy's greatest contribution to the history of medicine as a discipline was achieved in his nearly 30 years on the faculty at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, where he and his staff in the Department of Military Medicine and the Section of Medical History changed the perception of historians in the discipline towards military medicine—changing it from a cottage industry typically the domain of retired Medical Corps officers to a recognized sub-specialty in the history of medicine, one which could produce scholarly study as meaningful as any other area in the discipline.

Memorialization

[edit]

The Board of Regents of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences voted to memorialize Joy by naming Lecture Hall E--the freshman auditorium where Joy had done most of his lecturing during his career at the university—the Robert J. T. Joy Auditorium in his honor at a date to be determined. The auditorium is the second largest at the school, surpassed only by the Jay P. Sanford Auditorium.

Archival Holdings

[edit]The majority of Joy's personal and professional papers are deposited in the Archives of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland. An on-line finding aid is available.[77]

The Archival holdings from the U.S. Army Medical Research Team (WRAIR), including Joy's papers—over and above those unit records retired to the National Archives in College Park, Maryland—as well as records from Joy's tenure as commander of the WRAIR are in the Archives of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Forest Glen Annex, Silver Spring, Maryland.[78]

Joy's medical school notebooks are located in the Yale School of Medicine Archives in New Haven, Connecticut.[79]

Affiliations

[edit]Fellow, American College of Physicians

Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science

Fellow, College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Honorary Fellow, Wichita Surgical Society

Academy of Medicine of Washington, D.C.

Alpha Omega Alpha (Faculty)

American Physiological Society

American Association for the History of Medicine

The American Osler Society

History of Science Society

Society for Military History

Association of Military Surgeons of the United States

Washington Society for the History of Medicine

Awards and decorations

[edit]| 1st Row | Army Distinguished Service Medal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd Row | Legion of Merit with three bronze oak leaf clusters |

Air Medal | Army Commendation Medal | ||||||

| 3rd Row | National Defense Service Medal with bronze service star |

Vietnam Service Medal with three bronze service stars |

Vietnam Campaign Medal | ||||||

Unit Awards

![]()

Army Meritorious Unit Commendation[80]

![]()

Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Palm Unit Citation[81]

Badges

United States Army Senior Flight Surgeon Badge

Office of the Secretary of Defense Identification Badge

Promotions

[edit]| First Lieutenant, Medical Corps (MC) United States Army Reserve: 8 June 1954 [82] | |

| First Lieutenant, MC, Army of the United States: 25 June 1954 [83] | |

| First Lieutenant, MC, Regular Army: 24 June 1955 with Date of Rank 25 June 1953 [84] | |

| Captain, MC, Army of the United States: 10 February 1956 [85] | |

| Captain, MC, Regular Army: 23 March 1956 [86] | |

| Major, MC, Army of the United States: 21 March 1962 [87] | |

| Major, MC, Regular Army: 25 June 1964 [88] | |

| Lieutenant Colonel, MC, Army of the United States: 19 April 1966 [89] | |

| Colonel, MC, Army of the United States: | |

| Colonel, MC, Regular Army: |

Awards, Prizes, and Honors

[edit]1954 William Osler Medal, American Association for the History of Medicine[90]

1959 Hoff Memorial Medal for Achievement in Military Medicine, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research

1966 John Shaw Billings Award, Association of Military Surgeons of the United States

1980 William P. Clements Award for Outstanding Uniformed Services Educator, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences[91]

1986 Distinguished Member, Army Medical Department Regiment

1986 Order of Military Medical Merit

1990 Honorary Faculty, Industrial College of the Armed Forces, Washington, D.C.

1990 Outstanding Instructor Award, Class of 1993, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

1991 Outstanding Teacher Award, Class of 1994, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

1992 Faculty, United States Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine, San Antonio, Texas

1992 George M. Hunter Award as Senior Lecturer in Tropical Medicine, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research

1992 Outstanding Teacher Award, Class of 1995, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

1993 Outstanding Teacher Award, Class of 1996, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

1994 CADUSUHS, Class of 1994 Yearbook dedication, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

1995 Outstanding Teacher Award, Class of 1998, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

1996 Best Lecturer Award, Class of 1999, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

1996 Outstanding Civilian Educator of the Year, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences[92]

1996 Commencement Speaker, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences[93]

2002 Nicholas E. Davies Memorial Scholar Award in the Humanities and History of Medicine, American College of Physicians[94]

2012 Lifetime Achievement Award, American Association for the History of Medicine[95]

At its 2009 Commencement, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland awarded Joy the degree of Doctor of Military Medicine, Honoris Causa. The citation to accompany the degree read:

Colonel (retired) Robert J. T. Joy, MC, USA, FACP, was the first Commandant, first professor of military medicine, and first professor of medical history at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. His contributions to the academic discipline of military medicine and its history are without peer – with the assistance of his faculty and staff he created the academic discipline of military medicine as it is known today and he transformed the study of military medical history from the avocational pursuit of officers into an important scholarly component of two academic fields – medical history and military history.

When the Uniformed Services University School of Medicine opened in 1976, COL Joy was selected as the legislatively mandated Professor of Military, Naval or Aerospace Science. In this role he reflected on his experience in military medicine and his professional military education in the Armed Forces Staff College and realized that the United States Military had no joint medical doctrine or plans. COL Joy led USU to create a Department of Military Medicine and History in which students were instructed, texts were published, and integrative scholarship was practiced to create a joint military medicine for US forces. COL Joy outlined the medical school program in military medicine as it is still given more than 30 years later. His staff compiled textbooks which served as doctrine manuals for his students and his students wrote the joint medical doctrine as it exists today.

When he retired from active duty, Dr. Joy became the founding Professor of Medical History at USU. History had been an integral part of the military medical instructional program and while COL Joy’s protégés could continue the instruction in military medicine, he alone had the command of the military medical past which underlay much of the emerging doctrine; and so Dr. Joy built a second USU department. Shaping military medical history was in some ways more difficult than creating the Department of Military Medicine – there were academic disciplines of history already on the university scene and the new activity would need to be accepted by these disciplines. Through his own scholarship and the provision of encouragement and council to scholars in medical and military history as they attempt to bridge the gap that is the history of military medicine, Dr. Joy effectively created a new scholarly discipline. Dr. Joy is acknowledged in more than seventy published history books for his contributions to the author’s efforts. BG(ret) Robert Dougherty [sic], Professor & Chair of History at the United States Military Academy, summarized his impact: “No one else contributed as much as he to our understanding of military medicine and its history… his contribution has influenced, and will continue to influence, students, historians, and soldiers for decades to come.”[96]

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of Defense.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of Defense.

- ^ "Providence Journal (Sunday, October 12, 1997), obit for Narragansett MARY F. JOY, GenealogyBank.com: accessed 14 January 2020".

- ^ "Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Washington County, Rhode Island, Narragansett Township, Enumeration District 5-6, Sheet 1b: accessed 14 January 2020".

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "About the William Osler Medal".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 1 of 3".

- ^ Joy, R.J.T. "The Natural Bonesetters, with Special Reference to the Sweet Family of Rhode Island." Bulletin of the History of Medicine 28: 416-441, 1954."

- ^ "Yale Medicine Magazine: Medicine and the Military".

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "USAREUR Units & Kasernes 1945-1989: 4th Armored Group".

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "About the United States Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine".

- ^ "A Decade of Progress: The United States Army Medical Department 1959-1969, Chapter 8".

- ^ "About the United States Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine".

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "Vietnam Studies: Medical Support of the U. S. Army in Vietnam 1965-1970, Chapter 10".

- ^ "Vietnam Studies: Medical Support of the U. S. Army in Vietnam 1965-1970, Chapter 10".

- ^ "Vietnam Studies: Medical Support of the U. S. Army in Vietnam 1965-1970, Chapter 10".

- ^ Barr, Justin. "A short history of Dapsone, or an alternative model of drug development," Journal of the History of Medicine and the Allied Sciences, 66:4 (October, 2011)

- ^ "Vietnam Studies: Medical Support of the U. S. Army in Vietnam 1965-1970, Chapter 10".

- ^ "Lineage and Honors Statement, 6th Medical Center".

- ^ "Vietnam Studies: Medical Support of the U. S. Army in Vietnam 1965-1970, Chapter 10".

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 1 of 3".

- ^ Memorandum, MEDRI-CO, 19 May 1967, for: All Interested Personnel, Subject: Reading List in Military History and Military Medicine, forwarding a five page bibliography prepared by Joy.

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 1 of 3".

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 1 of 3".

- ^ Annual Report, the Surgeon General, United States Army, 1969

- ^ Annual Report, the Surgeon General, United States Army, 1970

- ^ O'Neil, William D. and Gene H. Porter, “What to Buy? The Role of Director of Defense Research and Engineering (DDR&E): Lessons from the 1970s,” IDA Paper P-4675 (Alexandria, Virginia: Institute for Defense Analyses, Jan 2011) http://handle.dtic.mil/100.2/ADA549549[permanent dead link].

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 1 of 3".

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "USAMRMC: 50 Years of Dedication to the Warfighter 1958–2008" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-08. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 1 of 3".

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Danny's Bar, no longer in business at its original location, was located at 1909 Seminary Road, just west of Georgia Avenue

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 1 of 3".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 1 of 3".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 1 of 3".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 1 of 3".

- ^ "Kinnamon, Kenneth E., Editor. 2004. The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: First Generation Reflections Page 169".

- ^ "Kinnamon, Kenneth E., Editor. 2004. The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: First Generation Reflections Pages 83-85. The Army allows award of the EFMB to medical personnel of any service who meet the testing requirements; wear of the badge is determined by the recipient's service".

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "Kinnamon, Kenneth E., Editor. 2004. The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: First Generation Reflections Page 171".

- ^ "Kinnamon, Kenneth E., Editor. 2004. The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: First Generation Reflections".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 1 of 3".

- ^ "Kinnamon, Kenneth E., Editor. 2004. The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: First Generation Reflections".

- ^ "Kinnamon, Kenneth E., Editor. 2004. The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: First Generation Reflections Pages 156-157".

- ^ "Kinnamon, Kenneth E., Editor. 2004. The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: First Generation Reflections Page 157".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 2 of 3".

- ^ "Kinnamon, Kenneth E., Editor. 2004. The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: First Generation Reflections Page 157".

- ^ "Kinnamon, Kenneth E., Editor. 2004. The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: First Generation Reflections Pages 158-159".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 2 of 3".

- ^ "Kinnamon, Kenneth E., Editor. 2004. The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: First Generation Reflections Pages 158-159".

- ^ "Kinnamon, Kenneth E., Editor. 2004. The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: First Generation Reflections Page 159".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 2 of 3".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 2 of 3".

- ^ "Kinnamon, Kenneth E., Editor. 2004. The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: First Generation Reflections Page 158".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 2 of 3".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 2 of 3".

- ^ "Kinnamon, Kenneth E., Editor. 2004. The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: First Generation Reflections Page 159".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 2 of 3".

- ^ Smith, Dale (January 8, 2020). "Dr. Robert J.T. Joy, Legendary USU Professor, Passes Away". Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 2 of 3".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 2 of 3".

- ^ "Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Commencement Program, 1996".

- ^ "Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Commencement Program, 1995".

- ^ "Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Commencement Program, 1997".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 3 of 3".

- ^ "USU Oral History Interview Transcript Dr. Robert J.T. Joy Part 3 of 3".

- ^ "Yale Medicine Magazine: Medicine and the Military".

- ^ "American Association for the History of Medicine Newsletter, February 2020: Obituaries: Robert John Thomas Joy (1929-2019)" (PDF).

- ^ "Dr. Robert J. T. Joy Papers: A Finding Aid to the collection in the James A. Zimble Learning Resource Center".

- ^ "US Army Medical Research Team Vietnam Finding Aid" (PDF).

- ^ "Robert J. T. Joy Student Notes from Yale School of Medicine finding aid".

- ^ "Headquarters, Department of the Army General Order 17, dated 23 April 1968, Paragraph II-118" (PDF).

- ^ "Headquarters, Department of the Army General Order 8, dated 19 March 1974, Paragraph I-3" (PDF).

- ^ "Official Army Register, 1956, Volume 1, Page 442".

- ^ "Official Army Register, 1956, Volume 1, Page 442".

- ^ "Official Army Register, 1956, Volume 1, Page 442".

- ^ "Official Army Register, 1960, Volume 1, Page 556".

- ^ "Official Army Register, 1960, Volume 1, Page 556".

- ^ "Official Army Register, 1964, Volume 1, Page 274".

- ^ "Official Army Register, 1966, Volume 1, Page 296".

- ^ "Official Army Register, 1968, Volume 1, Page 209".

- ^ "listing of past Osler Medal winners".

- ^ "Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences School of Medicine Commencement Program, 1980".

- ^ "Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Commencement Program, 1996".

- ^ "Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Commencement Program, 1996".

- ^ "Listing of recipients of American College of Physicians awards, page 16" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2020-01-14.

- ^ "Yale Medicine, Autumn, 2012: Robert J. T. Joy".

- ^ "2009 Commencement Program, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, pages 52-53".

- 1929 births

- 2019 deaths

- United States Army Medical Corps officers

- United States Army personnel of the Vietnam War

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army)

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Recipients of the Air Medal

- 20th-century American physicians

- Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences faculty