Saipan, Northern Mariana Islands

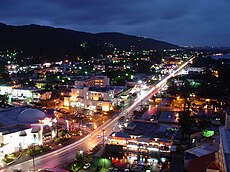

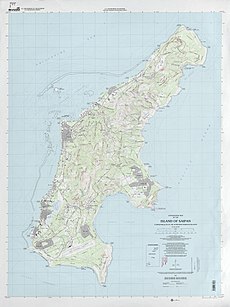

Top: Garapan Skyline; Bottom: Topographic map of Saipan Island | |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 15°11′N 145°45′E / 15.183°N 145.750°E |

| Archipelago | Marianas |

| Area | 118.98 km2 (45.94 sq mi)[1] |

| Length | 12 mi (19 km) |

| Width | 5.6 mi (9 km) |

| Highest elevation | 1,560 ft (475 m) |

| Highest point | Mount Tapochau |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| Commonwealth | Northern Mariana Islands |

| Largest settlement | Garapan |

| Mayor | Ramon Camacho |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Chamorro; Carolinian (Refaluwasch) |

| Population | 43,385 (2020) |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

| ZIP code | 96950 |

| Area code(s) | 670 |

| ISO code | 580 |

| Official website | https://governor.gov.mp |

Saipan[2] (/saɪˈpæn/) is the largest island and capital of the Northern Mariana Islands, a Territory of the United States in the western Pacific Ocean. According to 2020 estimates by the United States Census Bureau, the population of Saipan was 43,385.[3] Its people have been United States citizens since the 1980s. Saipan is one of the main homes of the Chamorro, the indigenous people of the Mariana Islands.

Saipan has been inhabited for over four thousand years. From the 17th century, the island experienced Spanish occupation and rule until the Spanish–American War of 1898, when Saipan was briefly occupied by the United States, before being formally sold to Germany. About 15 years of German rule were followed by 30 years of Japanese rule, which was ended by the Battle of Saipan, as the United States began to take control of the Philippine Sea. Following World War II, Saipan became part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, and was administered by the United States, along with rest of the Northern Marianas. In 1978, Saipan formally joined the United States as part of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

Today, Saipan is home to about 90% of the population of the Northern Mariana Islands. It hosts many resorts, golf courses, beaches, nature sites, and WW2 historical sites. The legislative and executive branches of Commonwealth government are located in the village of Capitol Hill on the island while the judicial branch is headquartered in the village of Susupe. Since the entire island is organized as a single municipality, most publications designate Saipan as the Commonwealth's capital. As of 2023, Saipan's mayor is Ramon Camacho and the governor of the Northern Mariana Islands is Arnold Palacios.

Saipan was hit by Typhoon Yutu in 2018, which caused widespread damage.

Etymology

[edit]In the Chamorro language, the island is called Saipan. Carolinian people who wished to claim prior inhabitance of the island have asserted that the name derives from the Carolinian word sááypéél (literal meaning, "a voyage empty"), in reference to a legendary Carolinian voyage of discovery of the primordial island.[4][5]

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]Traces of human settlements on Saipan have been found by archaeologists ranging over 4,000 years, including petroglyphs, ancient Latte Stones, and other artifacts pointing to cultural affinities with Melanesia and with similar stone monuments in Micronesia and Palau.[citation needed]

Spanish colonial period

[edit]Saipan, together with Tinian, was possibly first sighted by Europeans during the Spanish expedition of Ferdinand Magellan, when it made a landing in the southern Marianas on March 6, 1521.[6] It is likely Saipan was sighted by Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa in 1522 on board of Spanish ship Trinidad, which he commanded after the death of Ferdinand Magellan who died in the Battle of Mactan in Cebu, Philippines.[7] This is likely to have occurred after the sighting of the Maug Islands between the end of August and the end of September 1522.

Gonzalo de Vigo deserted in the Maugs from Gomez de Espinosa's Trinidad and during the next four years, living with the local indigenous Chamorro people, visited thirteen main islands in the Marianas and possibly Saipan among them. The first clear evidence of Europeans arriving to Saipan was by the Manila galleon Santa Margarita commanded by Juan Martínez de Guillistegui, that wrecked on the island in February 1600 and whose survivors stayed on it for two years, until 250 were rescued by the Santo Tomas and the Jesus María.[8]

The Spanish formally occupied the island in 1668, with the missionary expedition of Diego Luis de San Vitores who named it San José. After 1670, it became a port of call for Portuguese, Spanish, occasional English, Dutch and French ships as a supply station for food and water.[9] The native population shrank dramatically due to European-introduced diseases and conflicts over land. The Chamorros were forcibly relocated to Guam fearing the spread of leprosy in 1720 for better control and assimilation. Under Spanish rule, the island was developed into ranches for raising cattle and pigs, which were used as provision for Spanish galleons originating from the Philippines on their way to Mexico and vice versa.

Around 1815, many Carolinians[10][11] from Satawal settled Saipan during a period when the Chamorros were imprisoned on Guam, which resulted in a significant loss of land and rights for the Chamorro natives. The Caroline Islands had suffered a devastating typhoon that destroyed their crops. The leader of this company was an individual named "Chief Aghurubw," who sailed to Guam to ask the Spanish governor permission to settle on the islands. The Spaniards allowed Chief Aghurubw to settle on the island of Saipan.[citation needed] The Marianas archipelago was under the protectorate of the Spanish General Government of the Philippines; the Guardia Civil and Macabebe soldiers of the Province of Pampanga frequently made port calls to the islands to ensure law and order.[clarification needed]

German colonial period

[edit]After the Spanish–American War of 1898, Saipan was occupied by the United States. However, it was then sold by Spain to the German Empire[12] under the terms of the German–Spanish Treaty of 1899.

The island was administered by Germany as part of German New Guinea, but during the German period, there was no attempt to develop or settle the island, which remained under the control of its Spanish and mestizo landowners.[citation needed]

Japanese colonial period

[edit]

In 1914, during World War I, the island was captured by the Empire of Japan. Japan was awarded formal control of the island in 1919 by the League of Nations as a part of its mandated territory of the South Seas Mandate. Militarily and economically, Saipan was one of the most important islands in the mandate and became the center of subsequent Japanese settlement. Immigration began in the 1920s by ethnic Japanese, Koreans, Taiwanese and Okinawans, who developed large-scale sugar plantations. The South Seas Development Company built sugar refineries and—under Japanese rule—extensive infrastructure development occurred, including the construction of port facilities, waterworks, power stations, paved roads and schools, along with entertainment facilities and Shinto shrines. By October 1943, Saipan had a civilian population of 29,348 Japanese settlers and 3,926 Chamorro and Carolinian Islanders.[13]

World War II

[edit]

Japan considered Saipan to be part of the last line of defenses for the Japanese homeland, and thus had strongly committed to defending it. The Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy garrisoned Saipan heavily from the late 1930s, building numerous coastal artillery batteries, shore defenses, underground fortifications and an airstrip. In mid-1944, nearly 30,000 troops were based on the island.

The Battle of Saipan,[14] from June 15 to July 9, 1944, was one of the major campaigns of World War II. The United States Marine Corps and United States Army landed on the beaches of the south-western side of the island and, after more than three weeks in heavy fighting, captured the island from the Japanese. The battle cost the Americans 3,426 killed and 10,364 wounded.

Of the estimated 30,000 Japanese defenders, only 921 were taken prisoner. The weapons used, and the tactics of close quarter fighting, also resulted in high civilian casualties. Some 20,000 Japanese civilians perished during the battle, including over 1,000 who jumped from "Suicide Cliff" and "Banzai Cliff" rather than be caught and taken prisoner.[15]

Seabees of the U.S. Navy also landed, to initiate construction projects. With the capture of Saipan, the American military was only 1,300 miles (2,100 km) from the Japanese home islands, which placed most Japanese cities within striking distance of United States' B-29 Superfortress bombers. The loss of Saipan was a heavy blow to both the military and civilian administration of Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō, who was forced to resign.[16]

The wartime history is interpreted on Saipan at American Memorial Park and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Museum of History and Culture. After the war, nearly all of the surviving Japanese settlers were repatriated to Japan.[citation needed]

U.N. trust territory

[edit]After World War II, Saipan became part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, administered by the United States.

The U.S. bases on Saipan closed or were converted to other purposes, for example the Naval Advance Base Saipan from 1962 to 1986 was the headquarters for the U.N Trusteeship.[17] East Field airbase was used as an airport until the 1960s, after its military use ended in 1946. Later on the area was made into a golf course.

United States commonwealth

[edit]The Northern Mariana islanders voted to join the United States in 1975, and the island became a municipality of the newly-formed Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands in 1978.[18] On November 4, 1986, the islanders of the Northern Marianas including Saipan became United States citizens and the Northern Marianas formally became a part of the United States of America.[19] This meant that U.S. citizens could visit or live in Saipan and the rest of the CNMI without a passport and vice versa.[20]

Geography

[edit]

Saipan is the largest island in the Northern Mariana Islands. It is about 120 mi (190 km) north of Guam and 5 nautical miles (9.3 km) northeast of Tinian, from which it is separated by the Saipan Channel. Saipan is about 12 mi (19 km) long and 5.6 mi (9.0 km) wide, with a land area of 115.38 km2 (44.55 sq mi).

The western side of the island is lined with sandy beaches and an offshore coral reef creates a large lagoon. The eastern shore is composed primarily of rugged rocky cliffs and a reef. A narrow underwater bank of Marpi Reef lies 28 mi (45 km) north of the Saipan,[21] and CK Reef lies in the west of the island.[22]

The highest elevation on Saipan is a limestone-covered mountain called Mount Tapochau at 1,560 ft (480 m). Unlike many of the mountains in the Mariana Islands, it is not an extinct volcano but is a limestone formation.[23]

To the north of Mount Tapochau towards Banzai Cliff, is a ridge of hills. Mount Achugao, situated about 2 miles north, has been interpreted to be a remnant of a stratified composite volcanic cone whose Eocene center was not far north of the present peak.[24]

Saipan has some additional semi-attached islets, one of which being Bird Island, which is a nature reserve for birds. It is connected to Saipan only at low tide.[25] Forbidden Island is similar, but larger on the south east side of Saipan.[26] Mañagaha is a small 100 acre island off the west coast, and is a popular tourist destination. Access is by ferry, which is about ten minutes from the mainland.

An underwater limestone cavern called the Grotto, is up to 20 meters (70 feet) deep.[27]

Ecology

[edit]Several wildlife conservations areas have been designated on Saipan: Bird Island Wildlife Conservation Area, Kagman Wildlife Conservation Area, Lake Susupe Conservation Area, Megapode Conservation Areas, Saipan Upland Mitigation Bank, and the Costco Park Wetland Mitigation Pond.[28]

Flora

[edit]

The flora of Saipan is predominantly limestone forest. Some developed areas on the island are covered with Leucaena leucocephala, also known as "tangan-tangan" trees, which were spread broadly sometime after World War II. Tangan-Tangan trees were introduced, primarily, as an erosion-prevention mechanism, due to the decimation of the landscape brought on by World War II. Remaining native forest occurs in small, isolated fragments on steep slopes at low elevations and highland conservation areas of the island.

Coconuts, papayas, and Thai hot peppers – locally called "donni' såli" or "boonie peppers" – are among the fruits that grow wild. Mangoes, taro root, breadfruit (locally called "Lemai"), and bananas are a few of the many foods cultivated by local families and farmers.

Fauna

[edit]Saipan is home to numerous endemic bird species, including the Mariana fruit dove, white-throated ground dove, bridled white-eye, golden white-eye, Micronesian myzomela and the endangered Saipan reed warbler.[29] Multiple areas on Saipan, including the Sabana, Bird Island, Mount Topachau, Susupe, and Kagman, have been recognized as Important Bird Areas (IBA) by BirdLife International because they provide habitat for many different bird species.[30]

The island used to have a large population of giant African land snails, introduced either deliberately as a food source, or accidentally by shipping, which became an agricultural pest.[31] In the last few decades, its numbers have been substantially controlled by an introduced flatworm, Platydemus manokwari.

Climate

[edit]Saipan has a borderline tropical rainforest climate (Köppen Af)/tropical monsoon climate (Köppen Am), moderated by seasonal trade winds from the northeast from November to March, and easterly winds from May to October. Average year-round maximum temperature is 84 °F or 28.9 °C. There is little seasonal temperature variation, and Saipan has been cited by the Guinness Book of World Records as having the least fluctuating temperatures in the world. However, the temperature is affected by elevation; hence, the island shows considerable variations between the coastal and mountainous areas.

The drier season runs from December to June and the rainier season from July to November. Typhoon season runs from July to December, and Saipan, along with the rest of the Mariana Islands, is subject to at least one typhoon each year.

| Climate data for Saipan International Airport (1991–2020 normals, extremes 2000–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 89 (32) |

90 (32) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

96 (36) |

94 (34) |

99 (37) |

95 (35) |

94 (34) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

90 (32) |

99 (37) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 87.1 (30.6) |

86.7 (30.4) |

88.1 (31.2) |

89.3 (31.8) |

90.4 (32.4) |

91.1 (32.8) |

90.9 (32.7) |

90.9 (32.7) |

90.1 (32.3) |

89.2 (31.8) |

88.5 (31.4) |

88.0 (31.1) |

92.5 (33.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 84.1 (28.9) |

84.0 (28.9) |

84.9 (29.4) |

87.1 (30.6) |

88.2 (31.2) |

88.4 (31.3) |

87.8 (31.0) |

87.2 (30.7) |

87.2 (30.7) |

86.6 (30.3) |

86.5 (30.3) |

85.7 (29.8) |

86.5 (30.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 79.5 (26.4) |

79.1 (26.2) |

80.0 (26.7) |

82.0 (27.8) |

83.1 (28.4) |

83.4 (28.6) |

82.9 (28.3) |

82.4 (28.0) |

82.2 (27.9) |

81.8 (27.7) |

81.9 (27.7) |

81.0 (27.2) |

81.6 (27.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 74.8 (23.8) |

74.1 (23.4) |

75.2 (24.0) |

76.9 (24.9) |

78.0 (25.6) |

78.5 (25.8) |

78.1 (25.6) |

77.5 (25.3) |

77.2 (25.1) |

77.1 (25.1) |

77.3 (25.2) |

76.4 (24.7) |

76.8 (24.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 72.5 (22.5) |

71.5 (21.9) |

71.7 (22.1) |

73.4 (23.0) |

75.1 (23.9) |

75.7 (24.3) |

74.6 (23.7) |

73.5 (23.1) |

74.0 (23.3) |

73.9 (23.3) |

74.0 (23.3) |

73.9 (23.3) |

70.6 (21.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 70 (21) |

69 (21) |

69 (21) |

70 (21) |

73 (23) |

72 (22) |

71 (22) |

69 (21) |

72 (22) |

69 (21) |

69 (21) |

69 (21) |

69 (21) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 3.65 (93) |

2.50 (64) |

1.96 (50) |

2.75 (70) |

3.12 (79) |

4.24 (108) |

7.43 (189) |

12.86 (327) |

11.42 (290) |

10.72 (272) |

5.21 (132) |

3.78 (96) |

69.64 (1,769) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 17.4 | 15.3 | 14.2 | 16.4 | 17.9 | 20.2 | 24.3 | 23.9 | 23.3 | 24.5 | 20.7 | 18.9 | 237.0 |

| Source: NOAA (mean maxima/minima 2006–2020)[32][33] | |||||||||||||

Music

[edit]Music on Saipan can generally be broken down into three categories: local, mainland American, and Asian. Local consists of Chamorro, Carolinian, Micronesian Hawaiian Reggae and Palauan music, often with traditional dance for many occasions. Mainland American consists of much of the same music that can be found on U.S. radio. Asian consists of Japanese, Korean, Thai and Philippine music, among others. There are seven radio stations on Saipan, which play mainly popular and classic English-language songs as well as local and Philippine music.[34]

In 2017, an album called Music Of The Marianas: Made In Saipan Vol.1, featured 20 songs from a diverse collection of CNMI artists, released by 11th World Productions.[35] The CD features artists ranging from Church choral works, to mellow acoustic works, and underground island hip-hop.[35]

Television

[edit]Local television stations on Saipan are the following:

- KPPI-LP (ABC7), the ABC affiliate (simulcasts KTGM), which is owned by Sorensen Media Group.

- KSPN 2, which is owned by the Flame Tree Network.

- The Visitors Channel 3, which is owned by the Flame Tree Network.

- WSZE-TV 10, the NBC affiliate (repeats KUAM-TV in Guam), which is owned by Pacific Telestations.

Transportation

[edit]

Travel to and from the island is available from nine international airlines via Saipan International Airport. A small airline based on Tinian flies small twins to the islands of the Northern Marianas, typically short flights from island to island and Guam. A ferry once operated between Saipan and Tinian but was halted in 2010, reportedly for maintenance, and was never reinstated.

One of the island's two main thoroughfares, Beach Road, is located on the western coast of Saipan. At some parts of the road, the beach is only a few feet away. Flame trees and pine trees line the street. The street also connects more than six villages that lie on the western coast of the island. Middle Road is the island's largest road and runs through its central section. Like Beach Road, Middle Road connects several villages throughout the island. Several offices, shops, hotels, and residences lie on or nearby these highways. Middle Road is labeled "Chalan Pale Arnold" on maps, but very few people call it that. Aside from school buses, there is little to no public transportation on Saipan. Cars are the transportation of choice with motorcycles being the only other truly viable transportation method while bicycles are only viable in certain areas. Proper sidewalks are uncommon on the island with the majority located in Garapan and several at the corner turns of stoplights.

Villages and towns

[edit]

The island of Saipan has a total of 30 "official" villages. However, there are many sub-areas and neighborhoods located in certain villages such as Afetnas in San Antonio and Tapochau and I Denne in Capitol Hill. Those marked "SV:" are the sub-villages.

- As Lito

- As Matuis

- As Perdido

- Capitol Hill SV: I Denne, Tapochau, and Wireless Ridge

- Chalan Kanoa SV: Laly I, II, III, and IV

- Chalan Kiya

- Chalan Laulau SV: Quartermaster

- Chalan Piao

- Chinatown

- Dandan SV: Airport Road, Naftan, and Obyan

- Fina Sisu

- Garapan

- Gualo Rai

- Kagman SV: I, II, and III

- Kannat Tabla

- Koblerville SV: As Gonno

- Lower Base

- Marpi

- Navy Hill SV: Chalan Galaide and Rapagao

- Oleai

- Papago

- Sadog Tasi SV: As Mahetog

- San Antonio SV: Afetnas

- San Jose

- San Roque

- San Vicente SV: Lao Lao Beach

- Susupe

- Tanapag

Tourism

[edit]

Noted tourist destinations on Saipan include Managaha Island (100 acre tropical beach island visited by ferry), American Memorial Park and Micro Beach, a 1 km beach on the west side, making it possible to see the sun set.,[36] Latte Stones (old stones structures from the island's past), Mount Tapochau (highest point with views of Saipan), this site is known for its views and its possible to see other islands on clear day and is topped by a statue of Jesus Christ. Last Command Post (War history site of a Japanese command post in the WW2 Battle of Saipan), Bird Island Sanctuary beach (beach by Bird Island sanctuary), faces east. There is also a Bird Island observatory to the south for observing the birds),[37] Forbidden Island, a small island that is connected to Saipan at low tide and can be hiked onto, but at high tide the water separates the two. The island also features a lookout.,[38] Japanese Lighthouse (a lighthouse built in 1934 when the Northern Marianas were in the Japanese Mandate, currently a cafe with island views),[39] NMI Museum of History and Culture,[40] and The Grotto, a large underwater limestone cavern.[27]

Economy

[edit]Tourism had traditionally been a vital source of the island's revenue and economic activities. But in the 1980s, garment manufacturing became one of the main economic driving forces in Saipan when the U.S. government agreed that the CNMI would be exempted from certain federal minimum wage and immigration laws. While one result of these changes was an increase in hotels and tourism, the main consequence was that dozens of garment factories opened and clothing manufacturing became the island's chief economic force, employing thousands of foreign contract laborers (mostly young Chinese women) at low wages. The manufacturers could legally label these low cost garments "Made in the U.S.A." and the clothing shipped to the U.S. market was also exempt from U.S. tariffs. By 1998, the island's garment industry exported close to $1 billion worth of apparel products to the mainland. The working conditions and treatment experienced by employees in these factories were the subject of controversy and criticism.[41]

When the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) expired in 2005, thus eliminating quotas on textile exports to the United States, Saipan's garment factories started closing one after another. From a high of 34 garment factories in the late 1990s, By March 2007,[42] 19 companies manufactured garments on Saipan. In addition to many foreign-owned and run companies, many well-known U.S. brands also operated garment factories in Saipan for much of the last three decades. Brands included Gap,[43] Levi Strauss,[44] Phillips-Van Heusen,[45] Abercrombie & Fitch,[46] L'Oreal subsidiary Ralph Lauren (Polo),[47] Lord & Taylor,[48] Tommy Hilfiger, and Walmart.[49] By January 15, 2009, the island's last garment factory shuttered their doors.[50] On November 28, 2009, the federal government took control of immigration to the Northern Mariana Islands.[51]

More recently, casino gaming has come to Saipan with at least five casinos now operating on the island. As of 2016, Imperial Pacific International Holdings, a Chinese company listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (but majority owned by billionaire businesswoman Cui Lijie), which develops and operates casinos, hotels, and restaurants in CNMI, was reportedly the largest taxpayer in Saipan. In 2014, Imperial Pacific was granted a 25-year license to build and operate casinos on Saipan with an option to extend the license for another 15 years. The Imperial Pacific Resort, still unfinished as of June 2019, is set to include a luxury hotel, casino, restaurants, retail space, and leisure facilities. The complex was supposed to be completed by August 2018. The existing casinos are already handling over $2 billion monthly in VIP bets, more than the largest casinos in Macau, leading to accusations of money laundering.[52] There has been criticism by local doctors after dead and seriously injured Chinese workers have appeared at the hospital, often illegally working under tourist visas.[38]

Labor controversies

[edit]Jack Abramoff CNMI scandal

[edit]Jack Abramoff and his law firm were paid at least $6.7 million by the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) from 1995 to 2001 to change and/or prevent Congressional action regarding the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) and businesses on Saipan, its capital, commercial center, and one of its three principal islands.[53]

Later lobbying efforts involved mailings from a Ralph Reed marketing company and bribery of Roger Stillwell, a Department of the Interior official who in 2006 pleaded guilty to accepting gifts from Abramoff.[54]

Foreign contract labor abuse and exemptions from U.S. federal regulations

[edit]

Excerpted from "Immigration and the CNMI: A report of the US Commission on Immigration Reform", January 7, 1998:

The Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) immigration system is antithetical to the principles that are at the core of the US immigration policy. Over time, the CNMI has developed an immigration system dominated by the entry of foreign temporary contract workers. These now outnumber US citizens but have few rights within the CNMI and are subject to serious labor and human rights abuses. In contrast to US immigration policy, which admits immigrants for permanent residence and eventual citizenship, the CNMI admits aliens largely as temporary contract workers who are ineligible to gain either US citizenship or civil and social rights within the commonwealth. Only a few countries and no democratic society have immigration policies similar to the CNMI. The closest equivalent is Kuwait. The result of the CNMI policy is to have a minority population governing and severely limiting the rights of the majority population who are alien in every sense of the word.

On March 31, 1998,[55] US Senator Daniel Akaka said:

The Commonwealth shares our American flag, but it does not share the American system of immigration. There is something fundamentally wrong with a CNMI immigration system that issues permits to recruiters, who in turn promise well-paying American jobs to foreigners in exchange for a $6,000 recruitment fee. When the workers arrive in Saipan, they find their recruiter has vanished and there are no jobs in sight. Hundreds of these destitute workers roam the streets of Saipan with little or no chance of employment and no hope of returning to their homeland.

The State Department has confirmed that the government of China is an active participant in the CNMI immigration system. There is something fundamentally wrong with an immigration system that allows the government of China to prohibit Chinese workers from exercising political or religious freedom while employed in the United States. Something is fundamentally wrong with a CNMI immigration system that issues entry permits for 12- and 13-year-old girls from the Philippines and other Asian nations, and allows their employers to use them for live sex shows and prostitution.

Finally, something is fundamentally wrong when a Chinese construction worker asks if he can sell one of his kidneys for enough money to return to China and escape the deplorable working conditions in the Commonwealth and the immigration system that brought him there. There are voices in the CNMI telling us that the cases of worker abuse we keep hearing about are isolated examples, that the system is improving, and that worker abuse is a thing of the past. These are the same voices that reap the economic benefits of a system of indentured labor that enslaves thousands of foreign workers – a system described in a bi-partisan study as "an unsustainable economic, social and political system that is antithetical to most American values." There is overwhelming evidence that abuse in the CNMI occurs on a grand scale and the problems are far from isolated.

In 1991, Levi Strauss & Co. was embarrassed by a scandal involving six subsidiary factories run on Saipan by the Tan Holdings Corporation. It was revealed that Chinese laborers in those factories suffered under what the U.S. Department of Labor called "slavelike" conditions.[citation needed] Cited for sub-minimal wages, seven-day work week schedules with twelve-hour shifts, poor living conditions and other indignities (including the alleged removal of passports and the virtual imprisonment of workers), Tan would eventually pay what was then the largest fines in U.S. labor history, distributing more than $9 million in restitution to some 1200 employees. At the time, Tan factories produced 3% of Levi's jeans with the "Made in the U.S.A." label. Levi Strauss claimed that it had no knowledge of the offenses, severed ties to the Tan family, and instituted labor reforms and inspection practices in its offshore facilities.

In 1999, Sweatshop Watch, Global Exchange, Asian Law Caucus, Unite, and the garment workers themselves filed three separate lawsuits in class-action suits on behalf of roughly 30,000 garment workers in Saipan. The defendants included 27 U.S. retailers and 23 Saipan garment factories. By 2004, they had won a 20 million dollar settlement against all but one of the defendants.[56] Levi Strauss & Co. was the only successful defendant, winning the case against them in 2004.[56]

In 2005–2006, the issue of immigration and labor practices on Saipan was brought up during the American political scandals of Congressman Tom DeLay and lobbyist Jack Abramoff, who visited the island on numerous occasions. Ms. magazine published an exposé in their Spring 2006 article "Paradise Lost: Greed, Sex Slavery, Forced Abortion and Right-Wing Moralists".[57]

On February 8, 2007, the United States Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources received testimony about federalizing CNMI labor and immigration.[58]

On July 19, 2007,[59] Deputy Assistant Secretary of Insular Affairs David B. Cohen testified before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources Regarding S. 1634 (The Northern Mariana Islands Covenant Implementation Act).[59] He said:

Congress has the authority to make immigration and naturalization laws applicable to the CNMI. Through the bill that we are discussing today, Congress is proposing to take this legislative step to bring the immigration system of the CNMI under Federal administration. [...] [S]erious problems continue to plague the CNMI's administration of its immigration system, and we remain concerned that the CNMI's rapidly deteriorating fiscal situation may make it even more difficult for the CNMI government to devote the resources necessary to effectively administer its immigration system and to properly investigate and prosecute labor abuse. [...] While we congratulate the CNMI for its recent successful prosecution of a case in which foreign women were pressured into prostitution, human trafficking remains far more prevalent in the CNMI than it is in the rest of the U.S. During the twelve-month period ending on April 30, 2007, 36 female victims of human trafficking were admitted to or otherwise served by Guma' Esperansa, a women's shelter operated by a Catholic nonprofit organization. All of these victims were in the sex trade. Secretary Kempthorne personally visited the shelter and met with a number of women from the Philippines who were underage when they were trafficked into the CNMI for the sex industry. [...I]t is clear that local control over CNMI immigration has resulted in a human trafficking problem that is proportionally much greater than the problem in the rest of the U.S.

A number of foreign nationals have come to the Federal Ombudsman's office complaining that they were promised a job in the CNMI after paying a recruiter thousands of dollars to come there, only to find, upon arrival in the CNMI, that there was no job. Secretary Kempthorne met personally with a young lady from China who was the victim of such a scam and who was pressured to become a prostitute; she was able to report her situation and obtain help in the Federal Ombudsman's office. We believe that steps need to be taken to protect women from such terrible predicaments.

We are also concerned about recent attempts to smuggle foreign nationals, in particular Chinese nationals, from the CNMI into Guam by boat. A woman was recently sentenced to five years in prison for attempting to smuggle over 30 Chinese nationals from the CNMI into Guam.

A movement to federalize labor and immigration in the Northern Marianas Islands began in early 2007. A letter writing campaign to reform CNMI labor and immigration was debated in the local newspapers. Worker groups organized a successful Unity March December 7, 2007. Despite a strong lobby effort by Governor Fitial to stop it, President Bush signed PL 110-229 into law on May 8, 2008, and the U.S. immigration takeover began November 28, 2009.

Contract laborers arriving from China are usually required to pay their (Chinese National) recruitment agents fees equal to a year's total salary[60] (roughly $3,500) and occasionally as high as two years' salary,[55] though the contracts are only one-year contracts, renewable at the employer's discretion.

Sixty percent of the population of the CNMI is contract workers.[when?] These workers cannot vote. They are not represented, and can be deported if they lose their jobs. Meanwhile, the minimum wage remains well below that on the U.S. mainland, and abuses of vulnerable workers are commonplace.[61]

In John Bowe's 2007 book Nobodies: Modern American Slave Labor and the Dark Side of the New Global Economy, he provides a focus on Saipan, exploring how its culture, isolation and American ties have made it a favorable environment for exploitative garment manufacturers and corrupt politicos. Bowe goes into detail about the island's factories, and also its karaoke bars and strip joints, some of which have had connections with politicos. The author depicts Saipan as a vulnerable, truly suffering community, where poverty rates have climbed as high as 35 percent, and proposes that the guest worker setup, by allowing many native islanders to avoid work, has actually crippled the competitiveness and job readiness of the native population.

Chinese national, Chun Yu Wang, in her 2009 book, Chicken Feathers and Garlic Skin: Diary of a Chinese Garment Factory Girl on Saipan (as told to Walt F.J. Goodridge), provides the only known first-hand account of factory work conditions and life in the barracks, a historical timeline of the garment factory era on Saipan, and provides revealing insights from a Chinese perspective into the experience typical of many of the garment factory workers on Saipan.

Imperial Pacific Holdings Casino

[edit]On March 23, 2017, one of Imperial Pacific's Chinese construction workers fell off a scaffold and died. This led the Federal Bureau of Investigation to search one of Imperial Pacific's offices and make an arrest.[62] On February 15, 2018, Bloomberg Businessweek published an investigative report on the circumstances surrounding the death of this construction worker.[63] An attorney for the Torres Brothers law firm which represented this worker said the report omitted several facts about the case.[64] Imperial Pacific disputed all allegations of wrongdoing and sued Bloomberg for defamation.[65] The Federal Bureau of Investigation and U.S. Department of Homeland Security investigated the case and charged five individuals with harboring undocumented workers.[66] Companies linked to the governing Torres family have close links to the corporation, receiving $126,000 in 2017.[38]

Other local issues

[edit]Despite an annual rainfall of 80 to 100 inches (2,000 to 2,500 mm), the Commonwealth Utilities Corporation (CUC), the local government-run water utility company on Saipan, is unable to deliver 24-hour-a-day potable water to its customers in certain areas.[citation needed] As a result, several large hotels use reverse osmosis to produce fresh water for their customers. In addition, many homes and small businesses augment the sporadic and sometimes brackish water provided by CUC with rainwater collected and stored in cisterns. Most locals buy drinking water from water distributors and use tap water only for bathing or washing as it has a strong sulfur taste.

On October 18, 2018, Typhoon Yutu, the second strongest typhoon to have ever made impact on U.S. territory, made landfall on Saipan. With sustained winds of 130 mph and gusts up to 190 mph, it caused significant damage.

Demographics

[edit]

According to the 2010 United States Census,[67] Saipan's population was 48,220, a drop of 22.7% from the 2000 US Census; the population decrease is largely attributed to working immigrants and their families either returning to their home countries after the collapse of the garment industry or moving to other locations with economic opportunities such as Guam and the United States mainland. The population of Saipan corresponds to approximately 90% of the population of the Northern Mariana Islands.[68]

Large numbers of Filipino, Chinese, Bangladeshi, Nepalese and smaller numbers of Sri Lankan and Burmese unskilled workers and professionals migrated to the Northern Mariana Islands including Saipan during the late 1900s, mostly during the 1980s and 1990s.[69] In addition, a large percentage of the island's population includes first-generation immigrants and their descendants from Japan, China, Korea, the Philippines, Bangladesh and immigrants from other Micronesian islands.

According to the 2010 United States Census, Saipan was 50.9% Asian (35.3% Filipino, 6.8% Chinese, 4.2% Korean, 1.5% Japanese, 0.9% Bangladeshi, 0.5% Thai, 0.4% Nepalese, 0.3% Other Asian), 34.9% Pacific Islander (23.9% Chamorro, 4.6% Carolinian, 2.3% Chuukese, 2.2% Palauan, 0.8% Pohnpeian, 0.4% Yapese, 0.1% Kosraean, 0.1% Marshallese, and 0.5% Other Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander), 2.1% White and 0.2% others.[70]

Religion

[edit]The majority of the native Chamorro and Carolinian population are Roman Catholic. About half of the general population on the island are foreign contract workers, mainly Catholics of Filipino descent.

Numerous Christian churches are active in Saipan, providing services in various languages including English, Chamorro, Tagalog, Korean and Chinese.

In conjunction to the rest of the Northern Mariana Islands, there are Chinese and Filipino Protestant and Catholic churches, a Korean Protestant church, three mosques for the Bangladeshi community and a Buddhist temple.[69]

Education

[edit]

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Public School System serves Saipan. Public high schools:

- Kagman High School (Kagman)[71]

- Marianas High School (Susupe)

- Saipan Southern High School (Koblerville)[71]

There are many private schools on Saipan, including:

- Brilliant Star Montessori School - Navy Hill

- Saipan International School – As Lito

- Mount Carmel School – Chalan Kanoa

- Grace Christian Academy – Navy Hill

- Marianas Baptist Academy – Dandan

- Saipan Community School (grades K-8) – A Protestant school, it was established in 1976. Prior to SCS no Protestant schools were in Saipan.[72]

- Saipan Seventh-day Adventist School (18 months-grade 8)[73] – the previous campus of the Calvary School in Chalan Kiya[74][failed verification]

- Northern Marianas Academy (Fina Sisu).[75]

Northern Marianas College is a two-year community college serving the Northern Mariana Islands. Eucon International College is a four-year college that offers degrees in Bible and Education.

Joeten-Kiyu Public Library (JKPL) of the State Library of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands is in Susupe, Saipan.[76]

Japanese Community School of Saipan (サイパン日本人補習校 Saipan Nihonjin Hoshūkō), a supplementary Japanese school operated by the Japanese Society of the Northern Marianas (北マリアナ日本人会) Educational Department, is in Saipan. Classes are on the second floor of the USL Building in Gualo Rai. It was established on November 5, 1983 (Shōwa 58).[77][78]

- Public middle schools:

- Tanapag Middle School

- Hopwood Middle School

- Chacha Ocean View Middle School

- Francisco Mendiola Sablan Middle School

- Dandan Middle School

- Public elementary schools:

- Gregorio T. Camacho (GTC) Elementary School

- San Vicente Elementary School

- Koblerville Elementary School

- William S. Reyes Elementary School

- Kagman Elementary School

- Oleai Elementary School

- Garapan Elementary School

Notable people

[edit]

From Saipan

[edit]From the mainland United States

[edit]- Larry Hillblom: 1980s–1995

- William Millard: 1986–2011[79]

Appearances in literature and media

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (September 2022) |

Saipan was a major part of the plot in the Tom Clancy novel Debt of Honor.

The 1960 movie Hell to Eternity tells the true-life story of GI Guy Gabaldon's role in convincing 800 Japanese soldiers to surrender during the WWII Battle of Saipan. Key to Gabaldon's success was his ability to speak Japanese fluently due to having been raised in the 1930s by a Japanese-American foster family.

Much of the action in the 2002 film Windtalkers takes place during the invasion of Saipan during World War II.

In 2011, a Japanese film about Captain Sakae Ōba took place in Saipan. Titled Oba: The Last Samurai, it revolved around Oba holding out on Saipan until December 1, 1945.

A significant part of the novel Amrita by Japanese author Banana Yoshimoto takes place in Saipan with regular references to the landscape and spirituality of the island.

Saipan is the setting for the P. F. Kluge novel The Master Blaster. This novel is structured as first-person narratives of five characters, four of whom arrive on the same flight, and the unfolding of their experiences on the island. The book weaves together a mysterious tale of historical fiction with reference to Saipan's multi-ethnic past, from Japanese colonization to American WWII victory and the post-Cold War evolution of the island. The Master Blaster is the home-grown anonymous critic who blogs about the corruption and exploitation by developers, politicians, and government officials.

Saipan is known in the association football community as the site of the training camp for the Republic of Ireland national football team prior to the 2002 FIFA World Cup in which an incident of heated argument occurred between then-captain Roy Keane and then-manager Mick McCarthy, which eventually led to the dismissal and departure of Keane from the squad. This incident has come to be known colloquially as "the Saipan incident" or "the Saipan saga".

In 2016, a horror film directed by Hiroshi Katagiri was released on Netflix titled Gehenna: Where Death Lives in which American developers encounter a supernatural entity in a World War 2 hidden bunker while searching for land to build their resort.[80]

In 2024, Julian Assange visited briefly to plead guilty in the federal courthouse of the District Court for the Northern Mariana Islands, located in Saipan, to conspiracy to obtain and disclose US national defense information.[81]

See also

[edit]- Amelia Earhart § Speculation on disappearance

- Birth tourism

- Commonwealth (U.S. insular area)

- Kalabera

- List of populated places in the Northern Mariana Islands

- National Register of Historic Places listings in the Northern Mariana Islands

- Pedro Agulto Tenorio

- Saipan Sucks

References

[edit]- ^ "8 SAIPAN" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ^ (Chamorro: Sa’ipan, Carolinian: Seipél, formerly in Spanish: Saipán, and in Japanese: 彩帆島, romanized: Saipan-tō)

- ^ "Census Bureau Releases 2020 Census Population and Housing Unit Counts for the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands". Census.gov. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ Alkire, William H. (1984). "The Carolinians of Saipan and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands". Pacific Affairs. 57 (2): 270–283. doi:10.2307/2759128. ISSN 0030-851X. JSTOR 2759128.

- ^ "Legendary Setting". www.pacificworlds.com. Pacific Worlds & Associates. 2003. Archived from the original on May 1, 2023.

- ^ Rogers, Robert F.; Ballendorf, Dirk Anthony (1989). "Magellan's Landfall in the Mariana Islands". The Journal of Pacific History. 24 (2). Taylor & Francis Ltd.: 198. doi:10.1080/00223348908572614.

- ^ Donald D. The Pacific Basin: A History of its Geographical Explorations The American Geographical Society, New York, 1967, pg. 118.

- ^ Sharp, Andrew (1960). The discovery of the Pacific Islands. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Justo, Zaragoza "Descubrimientos de los españoles en el Mar del Sur y en las costas de la Nueva Guinea" Boletín de Sociedad Geográfica de Madrid, t.III. 1º semestre 1878, Madrid, p.44.

- ^ Worlds, RDK Herman, Pacific. "CNMI: Tanapag -- Arrival: Come Ashore". www.pacificworlds.com. Archived from the original on November 8, 2007. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Carolinian-Marianas Voyaging, Continuing the Tradition". Archived from the original on October 22, 2007.

- ^ Roberts, J. M. (2013). Hay, Denys (ed.). Europe 1880–1945. General History of Europe (3rd ed.). London: Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-1-317-87962-6. OCLC 870590864 – via ProQuest Ebook Central.

- ^ Patterson, Carolyn Bennett, et al. "At the Birth of Nations: In the Far Pacific." National Geographic Magazine, October 1986 page 498. National Geographic Virtual Library, Accessed May 17, 2018. The Japanese treated Saipan and its inhabitants as their colony. "The Japanese didn't treat us badly before World War II," said Governor "Pete" Tenorio. "Their policy, I believe, was to keep us native Chamorros out of harm's way. Before the Americans invaded Saipan in 1944, the Japanese had us move from our home on the coast to our farm in the hills. We kids never knew about the suicides until later."

- ^ "Battle of Saipan". History.com. August 21, 2018.

- ^ "Battle Of Saipan". HistoryNet. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ Immerwahr, Daniel (2019). How to hide an empire: a history of the greater United States (First ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-374-17214-5.

- ^ Seabees Construction

- ^ "Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands". US Office of Insular Affairs. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007.

- ^ "Proclamation 5564—United States Relations With the Northern Mariana Islands, Micronesia, and the Marshall Islands | The American Presidency Project". www.presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ "Do you need a passport to travel to or from U.S. territories or Freely Associated States? | USAGov". www.usa.gov. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ Pacific Islands Benthic Habitat Mapping Center. Saipan Island (& Marpi Bank) Archived March 27, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on March 27, 2017,

- ^ NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center. 2016. 2016 Marianas Humpback Whales – She's Baaaack! Archived March 27, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on March 27, 2017

- ^ Geological sections across Saipan Archived June 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (see section B), from Robert L. Carruth (2003), Ground-Water Resources of Saipan, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Archived October 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. USGS Water-Resources Investigation Report 03-4178, Honolulu, Hawaii.

- ^ Robert L. Carruth (2003), Ground-Water Resources of Saipan, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Archived October 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. USGS Water-Resources Investigation Report 03-4178, Honolulu, Hawaii.

- ^ "Latest travel itineraries for Bird Island in October (updated in 2023), Bird Island reviews, Bird Island address and opening hours, popular attractions, hotels, and restaurants near Bird Island". TRIP.COM. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ "Latest travel itineraries for Bird Island in October (updated in 2023), Bird Island reviews, Bird Island address and opening hours, popular attractions, hotels, and restaurants near Bird Island - Trip.com". TRIP.COM. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Grotto". AFAR Media. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ^ "Wildlife Conservation Areas | Department of Lands and Natural Resources". dlnr.cnmi.gov. Retrieved January 8, 2025.

- ^ "Nightingale Reed-warbler". Pacific Bird Conservation. Archived from the original on September 21, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ "Northern Saipan (Northern Mariana Islands (to USA)) IBA | Summary | BirdLife International". datazone.birdlife.org. Retrieved January 8, 2025.

- ^ Lange, W. Harry Jr. (October 1950). "Life History and Feeding Habits of the Giant African Snail on Saipan" (PDF). Pacific Science. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Saipan INTL AP, MP". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ List of radio stations in U.S. territories

- ^ a b Release, Press (January 4, 2017). "CD release party drops island music for NMI". Saipan Tribune. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ^ "Latest travel itineraries for Micro Beach in October (updated in 2023), Micro Beach reviews, Micro Beach address and opening hours, popular attractions, hotels, and restaurants near Micro Beach". TRIP.COM. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ "Bird Island Beach". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c "A Chinese Casino Has Conquered a Piece of America". Bloomberg.com. February 15, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Old Japanese Lighthouse". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ MVA (October 6, 2021). "NMI celebrates World Tourism Day". Marianas Variety News & Views. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ Howard P. Willens and Deanne C. Siemer. An Honorable Accord: the Covenant between the Northern Marianas and the United States. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press (Pacific Islands Monograph Series 18), 2003.

- ^ de la Torre, Ferdie (March 28, 2007). "Another garment firm closing". Saipan Tribune. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ "Women and Global Human Rights". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ "Green America: Printer friendly page". www.coopamerica.org. Archived from the original on September 24, 2006. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ "Responsible Shopper Profile: Phillips-Van Heusen". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ "Responsible Shopper Profile: Abercrombie & Fitch". Archived from the original on October 11, 2006.

- ^ "Responsible Shopper Profile: L'Oreal". Archived from the original on September 24, 2006.

- ^ "Responsible Shopper Profile: Lord & Taylor". Archived from the original on September 24, 2006.

- ^ Child Labor Wal-Mart Archived October 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Saipan Factory Facts: Information on the Rise and Fall of the Garment Industry on Saipan, CNMI Archived October 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Saipanfactorygirl.com. Retrieved on July 16, 2013.

- ^ "CNMI loses immigration control in 2009". Saipan Tribune. Archived from the original on January 3, 2010.

- ^ Campbell, Matthew (February 15, 2018). "A Chinese Casino Has Conquered a Piece of America". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on February 16, 2018. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ "M-01-05: Survey of CNMI-Contracted Lobbyist Activities, January 1994 through September 2001". Office of Public Auditor:Northern Mariana Islands. November 9, 2001. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2006.

- ^ "Recipient of Gifts From Abramoff Pleads Guilty". The Washington Post. Associated Press. August 12, 2006.

- ^ a b "Daniel Kahikina Akaka, U.S. Senator of Hawaii: Statements and Speeches". Archived from the original on June 2, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2011.

- ^ a b "Saipan Sweatshop Lawsuit Ends with Important Gains for Workers and Lessons for Activists". Archived from the original on May 28, 2007.

- ^ "Paradise Lost". msmagazine.com. Archived from the original on July 2, 2006. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ "Senate Hearing Airs Abuses of Women Laborers in Marianas". msmagazine. Archived from the original on April 3, 2007. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ a b "DOI Office of Insular Affairs (OIA)- Statement of David B. Cohen Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Insular Affairs Before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources Regarding S. 1634, The Northern Mariana Islands Covenant Implementation Act July 19, 2007". Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ^ "Wages and Savings of a Typical Saipan Garment Worker". www.oddcast.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2001.

- ^ "History of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI)". www.oddcast.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2001.

- ^ Campbell, Matthew; Farrell, Greg (April 1, 2017). "FBI Makes Arrest Related to Saipan Casino Construction". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ Campbell, Matthew (February 15, 2018). "A Chinese Casino Has Conquered a Piece of America". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on February 16, 2018. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Encinares, Erwin (February 20, 2018). "Lawyer: Bloomberg article left out key facts". Saipan Tribune. Archived from the original on May 28, 2018. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Stradbrooke, Steven (February 20, 2018). "Casino operator Imperial Pacific suing Bloomberg for defamation". CalvinAyre.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2018. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Chargualaf, Alana (June 5, 2018). "Woman sentenced in illegal foreign worker case". The Guam Daily Post. Archived from the original on August 23, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau Releases 2010 Census Population Counts for the Northern Mariana Islands". Archived from the original on December 23, 2010.

- ^ Starchild, Adam (April 1, 2000). Where to Legally Invest, Live & Work Without Paying Any Taxes. The Minerva Group, Inc. ISBN 9781893713130. Archived from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved November 13, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Crocombe, R. G. (January 1, 2007). Asia in the Pacific Islands: Replacing the West. editorips@usp.ac.fj. ISBN 9789820203884. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "American FactFinder – Results". census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ a b Home Page Archived March 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Public School System

- ^ "Saipan Community School Archived 2018-01-28 at the Wayback Machine." Saipan Community Church. Retrieved on January 15, 2018.

- ^ Home Archived January 15, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Saipan Seventh-day Adventist School. Retrieved on January 15, 2018.

- ^ "About Archived 2019-05-12 at the Wayback Machine." Saipan Seventh-day Adventist School. Retrieved on January 15, 2018.

- ^ "NMC Alumna Set to Graduate from Gonzaga University". Northern Marianas College. January 7, 2010. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ "Joeten-Kiyu Public Library calendar of events". Marianas Variety. May 12, 2017. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ "当校の概要 Archived 2016-08-29 at the Wayback Machine." Japanese Community School of Saipan (サイパン日本人補習校 Saipan Nihonjin Hoshūkō). Retrieved on January 14, 2018. "学校所在地 USL BUILDING 2nd Floor, GUALO RAI, SAIPAN, MP 96950 Commonwealth of The Northern Marianas Islands"

- ^ "北米の補習授業校一覧(平成25年4月15日現在)." () Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Japan). Retrieved on May 5, 2014. "サイパン Japanese Society of NMI Educational Department Japanese Society of NMI Educational Department PMB 165 Box 10000 Saipan, MP 96950 U.S.A."

- ^ Frank, Robert. (September 12, 2011) After 20 Years, Missing CEO Reappears – Yahoo! Finance Archived October 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-16.

- ^ Harvey, Dennis (April 30, 2018). "Film Review: 'Gehenna: Where Death Lives'". Variety. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ "WikiLeaks' Assange pleads guilty to publishing US military secrets in deal that secures his freedom". AP News. June 25, 2024. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

External links

[edit]- The Insular Empire: America in the Mariana Islands, PBS documentary film & website

- Saipan Municipality, United States Census Bureau

- Department of the Interior, Office of Insular Affairs – Links to cultural and informational sites about the CNMI as well as to government sites