Serer religion

| Part of a series on |

| Serers and Serer religion |

|---|

|

The Serer religion, or A ƭat Roog ("the way of the Divine"), is the original religious beliefs, practices, and teachings of the Serer people living in the Senegambia region in West Africa. The Serer religion believes in a universal supreme deity called Roog (or Rog). In the Cangin languages, Roog is referred to as Koox (or Kooh[1]), Kopé Tiatie Cac, and Kokh Kox.[2]

The Serer people are found throughout the Senegambia region. In the 20th century, around 85% of the Serer converted to Islam (Sufism),[3][4] but some are Christians or follow their traditional religion.[5] Traditional Serer religious practices encompass ancient chants and poems, veneration of and offerings to deities as well as spirits (pangool), initiation rites, folk medicine, and Serer history.

Beliefs

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Traditional African religions |

|---|

|

Divinity

[edit]The Serer people believe in a supreme deity called Roog (or Rog) and sometimes referred to as Roog Sene ("Roog The Immensity" or "The Merciful God").[6] Serer tradition deals with various dimensions of life, death, space and time, ancestral spirit communications and cosmology. There are also other lesser gods, goddesses and supernatural spirits or genie (pangool or nguus[7]) such as the fangool Mendiss (or Mindis), a female protector of Fatick Region and the arm of the sea that bears her name; the god Tiurakh (var : Thiorak or Tulrakh) – god of wealth, and the god Takhar (var : Taahkarr) – god of justice or vengeance.[8][9] Roog is neither the devil nor a genie, but the Lord of creation.[10]

Roog is the very embodiment of both male and female to whom offerings are made at the foot of trees, such as the sacred baobab tree, the sea, the river (such as the sacred River Sine), in people's own homes or community shrine, etc. Roog Sene is reachable perhaps to a lesser extent by the Serer high priests and priestesses (Saltigue), who have been initiated and possess the knowledge and power to organise their thoughts into a single cohesive unit. However, Roog is always watching over its children and always available to them.[11]

Divinity and humanity

[edit]In Serer, Roog Sene is the lifeblood to which the incorruptible and sanctified soul returns to eternal peace after they depart the living world. Roog Sene sees, knows and hears everything, but does not interfere in the day-to-day affairs of the living world. Instead, lesser gods and goddesses act as Roog's assistants in the physical world. Individuals have the free will to either live a good and spiritually fulfilled life in accordance with Serer religious doctrines or waver from such doctrines by living an unsanctified lifestyle in the physical world. Those who live their lives contrary to the teachings will be rightfully punished in the afterlife.[12]

Ancestral spirits and saints

[edit]Ordinary Serers address their prayers to the pangool (the Serer ancestral spirits and saints) as they are the intermediaries between the living world and the divine. An orthodox Serer must remain faithful to the ancestral spirits as the soul is sanctified as a result of the ancestors' intercession between the living world and the divine. The pangool have both a historical significance as well as a religious one. They are connected to the history of the Serer by virtue of the fact that the pangool is associated with the founding of Serer villages and towns as a group of pangool would accompany village founders called "lamane" (or laman – who were their ancient kings) as they make their journey looking for land to exploit. Without them, the lamane exploits would not have been possible. In the religious sense, these ancient lamanes created shrines to these pangool, thereby becoming the priests and custodians of the shrine. As such, "they became the intermediaries among the land, the people and the pangool".[13]

Whenever any member of the lamanic lineage dies, the whole Serer community celebrates in honour of the exemplary lives they had lived on earth in accordance with the teachings of the Serer religion. Serer prayers are addressed to the pangool who act as intercessors between the living world and the divine. In addressing their prayers to the pangool, the Serers chant ancient songs and offer sacrifices such as bull, sheep, goat, chicken or harvested crops.

Afterlife

[edit]The immortality of the soul and reincarnation (ciiɗ in Serer[14]) is a strongly held belief in Serer religion. The pangool are viewed as holy saints, and will be called upon and venerated, and have the power to intercede between the living and the divine. The Serer strive to be accepted by their ancestors who have long departed and to gain the ability to intercede with the divine. Failure to do so results in rejection by the ancestors and becoming a lost and wandering soul.[10][15]

Family totems

[edit]Each Serer family has a totem (tiim / tim[16]). Totems are prohibitions as well as guardians. They can be animals and plants among other beings. For example, the totem of the Joof family is the antelope. Any brutality against this animal by the Joof family is prohibited. This respect gives the Joof family holy protection. The totem of the Njie family is the lion; the totem of the Sène family is the hare and for the Sarr family is the giraffe and the camel.[17][18]

The secret order of the Saltigue

[edit]Both men and women can be initiated into the secret order of the Saltigue (Spiritual Elder). In accordance with Serer religious doctrines, for one to become a Saltigue, one must be initiated which is somewhat reserved for a small number of insiders, particularly in the mysteries of the universe and the unseen world. The Xooy (Xoy or Khoy) ceremony is a special religious event in the Serer religious calendar. It is the time when the initiated Saltigue (Serer High Priests and Priestesses) come together to literally predict the future in front of the community. These diviners and healers deliver sermons at the Xooy Ceremony which relates to the future weather, politics, economics, and so on.[19] The event brings together thousands of people to Holy Sine from all over the world. Ultra orthodox Serers and Serers who "syncretise" (mix Islam or Christianity with the old Serer religion) as well as non-Serers such as the Lebou people (who are a distinct group but still revere the ancient religious practices of their Serer ancestors) among others gather at Sine for this ancient ceremony. Serers who live in the West sometimes spend months planning for the pilgrimage. The event goes on for several days where the Saltigue take centre stage and the ceremony usually begins in the first week of June at Fatick.

Holy ceremonies and festivals

[edit]

Raan festival

[edit]The Raan festival of Tukar takes place in the old village of Tukar founded by Lamane Jegan Joof (or Lamane Djigan Diouf in French speaking Senegal) around the 11th century.[22][23] It is headed by his descendants (the Lamanic lineage). The Raan occurs every year on the second Thursday after the appearance of the new moon in April. On the morning of Raan, the Lamane would prepare offerings of millet, sour milk and sugar. After sunrise, the Lamane makes a visit to the sacred pond – the shrine of Saint Luguuñ Joof who guided Lamane Jegan Joof after he migrated from Lambaye (north of Sine). The Lamane would make an offering to Saint Luguuñ and spends the early morning in ritual prayer and meditation. After that, he makes a tour of Tukar and perform ritual offerings of milk, millet and wine as well as small animals at key shrines, trees, and sacred locations. The people make their way to the compound of the chief Saltigue (the Serer high priests and priestess – who are the "hereditary rain priests selected from the Lamane's lineage for their oracular talent").[24]

Religious law

[edit]Day of rest

[edit]In Serer religion, Monday is the day of rest. Cultural activities such as Njom or "Laamb" (Senegalese wrestling) and weddings are also prohibited on Thursday.[10]

Marriage

[edit]Courting for a wife is permitted but with boundaries. Women are given respect and honour in Serer religion. The woman must not be dishonoured or engaged in a physical relationship until after she has been married. When a man desires a woman, the man provides the woman gifts as a mark of interest. If the woman and her family accept, this then becomes an implied contract that she should therefore not court or accept gifts from another man whose aim is to court her.[25][26]

Premarital relationship

[edit]Were a young man and a woman found engaged in premarital relationships, both are exiled to avoid bringing shame to the family, even if pregnancy resulted from that courtship.[25]

Adultery

[edit]Adultery is dealt with by the Serer jurisprudence of Mbaax Dak A Tiit (the rule of compensation).[27] If a married woman engaged in adultery with another man, both adulterers are humiliated in different ways. The wronged male spouse (the husband) is entitled to take the undergarment of the other male and hang it outside his house to show that the male lover had broken custom by committing adultery with his wife. The lover would be shunned from the Serer society; no family would want to marry into his family and he would be excommunicated. This was and is seen as extremely humiliating; many male Serers have been known to take their own lives because they couldn't bear the humiliation.[25][28] The public display of undergarments was not applied to women; when women marry in Serer society, they braid their hair in a particular style, which is restricted to married women – it is a symbol of their status, which is highly valued in Serer society. An adulteress's female relatives unbraid her hair. This is so humiliating and degrading for a married woman that many women have been known to commit suicide rather than endure the shame.[25][28] The wronged man can forgive both his wife and her lover if he chooses to. The adulterers and their respective families must gather at the king, chief, or elder's compound to formally seek forgiveness. This will be in front of the community because the rules that govern society have been broken. The doctrine extends to both married men and women. Protection is given to the wronged spouse regardless of his or her gender.[29][28]

Murder

[edit]

In the past, when someone killed another person, the victim's family had the right to either forgive or seek vengeance. The murderer and his family would gather at a local centre headed by the Chief or the palace headed by the King. Before this judgement, the murderer's family would cook some food (millet) to be shared among the community and the victim's family. The victim's family would nominate a strong man armed with a spear with a piece of cooked lamb or beef at the end of it. This executioner, taking his instruction from the victim's family, would run towards the murderer, who was required to keep his mouth open. If the victim's family chose accordingly, the executioner would kill the murderer with his spear, after which the food that had been cooked would not be eaten and everyone would disperse. From that day on, the families would be strangers to each other. On the other hand, if the victim's family had forgiven the murderer, then would the executioner run and gently feed the murderer the piece of meat on his spear. In that case, the community would enjoy the meal and the two families would be sealed as one and sometimes even marry off their children to each other.[29][30]

Religious attire

[edit]Serers may wear an item belonging to their ancestor, such as the hair of an ancestor or an ancestor's treasured belonging, which they turn into juju on their person or visibly on their necks.[31]

Medicine, harvest and offerings

[edit]The Serers also have an ancient knowledge of herbalism which is passed down and takes years to acquire.[32][33] The Senegalese government has set a school and centre to preserve this ancient knowledge and teach it to the young. The CEMETRA (Centre Expérimental de Médecine Traditionnelle de Fatick) Membership alone consist of at least 550 professional Serer healers in the Serer region of Sine-Saloum.[34]

Several traditional practices linked with land and agricultural activities are known, two examples are described below:

- Prediction ceremonies organized by the Saltige, who are considered to be the custodians of indigenous knowledge. Such meetings are aimed at providing information and warning people about what will happen in the village during the next rainy season.

- Preparation of sowings, a ceremony called Daqaar mboob aimed at ensuring good millet or groundnut production. For this purpose, every grower has to obtain something called Xos, further to a competitive ceremony consisting of hunting, racing, etc.[32]

Influence on Senegambia

[edit]As the old pagan festivals were borrowed and altered by Christianity which came later,[35] the names of ancient Serer religious festivals were also borrowed by Senegambian Muslims in a different way to describe genuine Islamic festivals in their own language. The Serers are one of very few communities in Senegambia, apart from the Jolas, who have a name for god[s] which is not borrowed from Arabic but indigenous to their language.[36] Tobaski (var : Tabaski) was an ancient Serer hunting festival; Gamo was an ancient Serer divination festival; Korite [from the Serer word kor[37]] was a male initiation rite; Weri Kor was the season (or month) Serer males went through their initiation rites. Gamo (comes from the old Serer word Gamahou, variation : Gamohou). "Eid al kabir" or "eidul adha" (which are Arabic) are different from Serer Tobaski, but the Senegambian Muslims loaned Tobaski from Serer religion to describe "Eid al Kabir". Gamo also derives from Serer religion.[38][39] The Arabic word for it is "Mawlid" or "Mawlid an-Nabi" (which celebrates the birth of Muhammad). Weri Kor (the month of fasting, "Ramadan" in Arabic) and Koriteh or Korité ("Aïd-el-fitr" in Arabic which celebrates the end of the month of fasting) also comes from the Serer language.

Mummification and the cult of the Upright Stones

[edit]

The dead, especially those from the upper echelons of society, were mummified in order to prepare them for the afterlife (Jaaniiw). They were accompanied by grave goods including gold, silver, metal, their armour and other personal objects. Mummification is less common now, especially post-independence.[40][30][41][42] The dead were buried in a pyramid shaped tomb.[30][43]

The Serer griots play a vital and religious role on the death of a Serer King. On the death of a Serer king, the Fara Lamb Sine (the chief griot in the Serer Kingdom of Sine) would bury his treasured drum (the junjung) with the king. His other drums would be played for the last time before their burial in the ground facing east. The griots then chant ancient songs marked by sadness and praise for the departed king. The last time this ceremony occurred was on 8 March 1969 following the death of the last king of Sine – Maad a Sinig Mahecor Joof (Serer: Maye Koor Juuf).[44]

The cult of the Upright Stone, such as the Senegambian stone circles, which were probably built by predecessors of the Serer,[47][48][49][50] were also a place of worship. Laterite megaliths were carved, planted, and directed towards the sky.[51][52][53]

Cosmology

[edit]

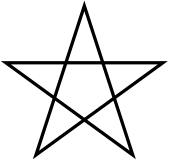

One of the most important cosmological stars of the Serer people is called Yoonir. The "Star of Yoonir" is part of the Serer cosmos. It is very important and sacred and just one of many religious symbols in Serer religion and cosmology. It is the brightest star in the night sky, Sirius. With an ancient heritage of farming, "Yoonir" is very important and sacred in Serer religion,[55][56] because it announces the beginning of flooding and enables Serer farmers to start planting seeds. The Dogon people of Mali call it "Sigui", whilst in Serer it is called "Yoonir"[57] – represented in the form of the "Pangool" (interceders with Roog – the Supreme Deity) and "Man". It is before this event where the Serer High Priests and Priestesses known as Saltigue gather at the Xooy annual divination ceremony where they predict the course of the winter months among other things relevant to the lives of the Serer people.[58][59] The Pangool (singular : Fangool) are ancestral spirits (also ancient Serer Saints in Serer religion) represented by snakes.

The peak of the Star (top point) represents the Supreme Deity (Roog). The other four points represent the cardinal points of the Universe. The crossing of the lines ("bottom left" and "top right" and "top left and bottom right") pinpoints the axis of the Universe, that all energies pass. The top point is "the point of departure and conclusion, the origin and the end".[46] Among the Serers who cannot read or write the Latin alphabet, it is very common for them to sign official documents with the Star of Yoonir, as the Star also represents "good fortune and destiny".[46]

Religious devotion and martyrdom

[edit]While most Serers converted to Islam and Christianity (specifically Roman Catholic), their conversion was after colonization. They and the Jola people were the last to convert to these religions.[60][61] Many still follow the Serer religion especially in the ancient Kingdom of Sine with Senegal and the Gambia being predominantly Muslim countries.[60][61]

The Serers have also battled many prominent African Islamic jihadists over the centuries. Some of those like Maba Diakhou Bâ is considered a national hero and given a saint like status by Senegambian Muslims. He himself was killed in battle fighting against the Serer King of Sine – Maad a Sinig Kumba Ndoffene Famak Joof on 18 July 1867 at The Battle of Fandane-Thiouthioune commonly known as The Battle of Somb.[62][63]

At the surprise attacks of Naodorou, Kaymor and Ngaye, where the Serers were defeated, they killed themselves rather than be conquered by the Muslim forces. In these 19th-century Islamic Marabout wars, many of the Serers villagers committed martyrdom, including jumping to their deaths at the Well of Tahompa.[64] In Serer religion, suicide is only permitted if it satisfies the Serer principle of Jom (also spelt "Joom" which literally means "honour"[65] in the Serer language) – a code of beliefs and values that govern Serer lives.[66][67]

See also

[edit]- Lamane

- Saltigue

- Serer creation myth

- States headed by ancient Serer Lamanes

- Timeline of Serer history

Notes

[edit]- ^ (in French) Dupire, Marguerite, Sagesse sereer: Essais sur la pensée sereer ndut, Karthala Editions (1994), p. 54, ISBN 2865374874.

- ^ (in French) Ndiaye, Ousmane Sémou, "Diversité et unicité sérères : l'exemple de la région de Thiès", Éthiopiques, no. 54, vol. 7, 2e semestre 1991 [1].

- ^ Olson, James Stuart (1996). The Peoples of Africa: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Greenwood. p. 516. ISBN 978-0313279188.

- ^ Leonardo A. Villalón (2006). Islamic Society and State Power in Senegal: Disciples and Citizens in Fatick. Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–74. ISBN 978-0-521-03232-2.

- ^ James Stuart Olson (1996). The Peoples of Africa: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Greenwood. p. 516. ISBN 978-0-313-27918-8.

- ^ (in French) Faye, Louis Diène, Mort et Naissance le monde Sereer, Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines (1983), ISBN 2-7236-0868-9. p. 44.

- ^ Nguus means genie. See : Kalis, p. 153.

- ^ Henry, Gravrand, La civilisation sereer, vol. II : Pangool, Nouvelles éditions africaines, Dakar (1990).

- ^ Kellog, Day Otis, and Smith, William Robertson, The Encyclopædia Britannica: latest edition. A dictionary of arts, sciences and general literature", Volume 25, p. 64, Werner (1902).

- ^ a b c Verbatim: "le Maître/Seigneur de la créature" (in French) Thaiw, Issa Laye, "La religiosité des Seereer, avant et pendant leur islamisation", in Éthiopiques, no. 54, volume 7, 2e semestre 1991.

- ^ Gravrand, "Pangool", pp. 205–8.

- ^ Fondation Léopold Sédar Senghor, Éthiopiques, Issues 55–56 (1991), pp. 62–95.

- ^ Galvan, Dennis Charles, The State Must Be Our Master of Fire: How Peasants Craft Culturally Sustainable Development in Senegal, Berkeley, University of California Press (2004), p. 53, ISBN 0520235916.

- ^ Ciiɗ means poetry in Serer, it can also mean the reincarnated or the dead who seek to reincarnate in Serer religion. Two chapters are devoted to this by Faye see: Faye, Louis Diène, Mort et Naissance Le Monde Sereer, Les Nouvelles Edition Africaines (1983), pp. 9–10, ISBN 2-7236-0868-9.

- ^ Faye, Louise Diène, Mort et Naissance le monde Sereer, Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines (1983), pp. 17–25, ISBN 2-7236-0868-9.

- ^ Dupire, Marguerite, "Sagesse sereer: Essais sur la pensée sereer ndut, KARTHALA Editions (1994), p. 116

- ^ Jean-Marc Gastellu (M. Sambe – 1937 [in]), L'égalitarisme économique des Serer du Sénégal, IRD Editions (1981), p. 130, ISBN 2-7099-0591-4.

- ^ (in French) Gravrand Henry, La civilisation sereer, vol. I : Cosaan: les origines, Nouvelles éditions africaines, Dakar (1983), p. 211, ISBN 2723608778.

- ^ Sarr, Alioune, "Histoire du Sine-Saloum" (introduction, bibliographie et notes par Charles Becker), in Bulletin de l'IFAN, tome 46, série B, nos 3–4, 1986–1987 pp. 31–38.

- ^ (in French) Niang, Mor Sadio, [in] Ethiopiques numéro 31" - révue socialiste de culture négro-africaine 3e trimestre, IFAN, (1982) – (From Xoy to Tourou Peithie) [2] Archived 24 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Seck, A.; Sow, I. & Niass, M., "Senegal", [in] "The biodiversity of traditional leafy vegetables", pp. 85–110.

- ^ Galvan, Dennis Charles, pp. 108–111 and 122, 304, University of California Press (2004) ISBN 0-520-23591-6.

- ^ Bressers, Hans, & Rosenbaum, Walter A., Achieving sustainable development: the challenge of governance across social scales, Greenwood Publishing Group (2003), p. 151, ISBN 0-275-97802-8.

- ^ Galvan, Dennis Charles, University of California Press (2004), p. 202, ISBN 0-520-23591-6.

- ^ a b c d Thiaw, Issa Laye, La femme Seereer (Sénégal), L'Harmattan, Paris, septembre (2005), pp. 92, 255–65, ISBN 2-7475-8907-2.

- ^ La Piallée No. 141. avril 2006. Dakar.

- ^ Thiaw, Issa Laye, La femme Seereer (Sénégal), [in] Fatou K. Camara, Moving from Teaching African Cusmary Laws to Teaching African Indigenous Law.

- ^ a b c Thaiw, Issa Laye, "La femme Seereer" (Sénégal), L'Harmattan, Paris, septembre (2005), p. 169, ISBN 2-7475-8907-2.

- ^ a b Thiaw, Issa Laye, Corporal Punishment in Seereer Customary Law pp. 25–28.

- ^ a b c Dupire, Marguerite, "Les tombes de chiens : mythologies de la mort en pays Serer" (Sénégal), Journal of Religion in Africa (1985), vol. 15, fasc. 3, pp. 201–215.

- ^ Joshua Project: "What are their beliefs?".

- ^ a b Secka, A.; Sow, I., and Niass, M., (Collaborators: A.D. Ndoye, T. Kante, A. Thiam, P. Faye and T. Ndiaye.) Senegal, Horticonsult The biodiversity of traditional leafy vegetables, pp. 85–110 [3][permanent dead link].

- ^ Kalis, Simone, Médecine traditionnelle, religion et divination chez les Seereer Siin du Sénégal, L'Harmattan, (1997), ISBN 2-7384-5196-9.

- ^ "Promotion de Medicine Traditionnelles" (in French). Prometra International, Prometra France. Archived from the original on 5 December 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ Biblical Archaeology Society. Bible review, Volumes 18–19. Published by: Biblical Archaeology Society, 2002. ISBN 0-9677901-0-7.

- ^ Wade, Amadou, "Chronique du Walo sénégalais (1186-1855)", (trans : B. Cissé), V. Monteil, Bulletin de l'IFAN, Series B, Vol. 26, no. 3/4. 1941, 1964.

- ^ Meaning man or male. Variation : gor as in Senghor

- ^ Diouf, Niokhobaye, "Chronique du royaume du Sine, suivie de Notes sur les traditions orales et les sources écrites concernant le royaume du Sine par Charles Becker et Victor Martin (1972)". (1972). Bulletin de l'IFAN, tome 34, série B, no 4, 1972, pp. 706–7 (pp. 4–5), pp. 713–14 (pp. 9–10).

- ^ (in French) Brisebarre, Anne-Marie, Kuczynski, Liliane, La Tabaski au Sénégal: Une fête musulmane en milieu urbain, Karthala Editions (2009), pp. 13, 141–200, ISBN 2-8111-0244-2.

- ^ Krzyżaniak, Lech; Kroeper, Karla & Kobusiewicz, Michał, "Muzeum Archeologiczne w Poznaniu", Interregional contacts in the later prehistory of northeastern Africa, Poznań Archaeological Museum (1996), pp. 57–58, ISBN 83-900434-7-5.

- ^ Diop, Cheikh Anta, The African origin of civilization: myth or reality L. Hill (1974), p. 197, ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- ^ African forum, Volumes 3–4, American Society of African Culture, (1967), p. 85.

- ^ (in French) Ndiaye, Ousmane Sémou, "Diversite et unicite Sereres: L'exemple de la Region de Thies" [in] Ethiopiques n°54, revue semestrielle de culture négro-africaine, Nouvelle série, volume 7 2e semestre (1991) (Retrieved : 10 May 2012).

- ^ (Faye, Louis Diène, Mort et Naissance le monde Sereer, Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines (1983), ISBN 2-7236-0868-9) [in] Boyd-Buggs, Debra; Scott, Joyce Hope, Camel Tracks: Critical Perspectives on Sahelian Literatures, Africa World Press (2003), p. 56, ISBN 0865437572 [4] (Retrieved : 10 May 2012).

- ^ Gravrand, La civilisation sereer : Pangool p. 20.

- ^ a b c Madiya, Clémentine Faïk-Nzuji, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Canadian Centre for Folk Culture Studies, "International Centre for African Language, Literature and Tradition", (Louvain, Belgium), pp. 27, 155, ISBN 0-660-15965-1.

- ^ Gravrand, Henry, La Civilisation Sereer - Pangool, Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal, 1990, p. 77, ISBN 2-7236-1055-1.

- ^ Gambian Studies No. 17., "People of The Gambia. I. The Wolof with notes on the Serer and the Lebou", By David P. Gamble & Linda K. Salmon with Alhaji Hassan Njie, San Francisco (1985).

- ^ Espie, Ian, A thousand years of West African history: a handbook for teachers and students, Editors: J. F. Ade Ajayi, Ian Espie, Humanities Press (1972), p. 134, ISBN 0391002171.

- ^ (in French) Becker, Charles: Vestiges historiques, trémoins matériels du passé clans les pays sereer. Dakar. 1993. CNRS - ORS TO M (Excerpt) (Retrieved : 28 June 2012).

- ^ Diop, Cheikh Anta, The African origin of civilization: myth or reality, L. Hill (1974), p. 196, ISBN 0-88208-021-0.

- ^ Gravrand, Henry, La Civilisation Sereer - Pangool, Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal (1990), pp. 9, 20 & 77, ISBN 2-7236-1055-1.

- ^ Becker, Charles, Vestiges historiques, trémoins matériels du passé clans les pays sereer, Dakar (1993), CNRS - ORS TO M.

- ^ Gravrand, Henry, Pangool, p. 216.

- ^ Berg, Elizabeth L., & Wan, Ruth, Cultures of the World: Senegal, Benchmark Books (New York) (2009), p. 144, ISBN 978-0-7614-4481-7.

- ^ Kalis, Simone, "Médecine Traditionnelle, Religion et Divination Chez les Seereer Siin du Sénégal" – La Coonaissance de la Nuit, L'Harmattan (1997), pp. 25–60, ISBN 2-7384-5196-9.

- ^ The following is an account of Henry Gravrand's description of the representation of "Yoonir", Serer ancestral links to the "Sahara" and the ancient relics of Thiemassas in modern day Senegal:

- "Fixed towards the sky or drawn on the ground.

- The Star (Yoonir)

- The Sereer symbol of the universe

- The five branches represents

- the black man standing head held high,

- hands raised representing

- work and prayer.

- Sign of God :Image of Man." (Gravrand, "Pangool" p. 21).

- ^ Gravrand, Henry, La civilisation Sereer Pangool, Les nouvelles Edition (1990), p. 20.

- ^ Madiya, Clémentine Faïk-Nzuji, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Canadian Centre for Folk Culture Studies, International Centre for African Language, Literature and Tradition, (Louvain, Belgium), Tracing memory: a glossary of graphic signs and symbols in African art and culture, Canadian Museum of Civilization (1996), pp. 5, 27, 115, ISBN 0-660-15965-1.

- ^ a b John Glover. Sufism and jihad in modern Senegal: the Murid order.

- ^ a b Conversion to Islam: Military Recruitment and Generational Conflict in a Sereer-Safin Village (Bandia).

- ^ Sarr, Alioune, Histoire du Sine-Saloum, Introduction, bibliographie et Notes par Charles Becker, BIFAN, Tome 46, Serie B, n° 3–4, 1986–1987, pp. 37–39.

- ^ Klein, Martin A., Islam and Imperialism in Senegal Sine-Saloum, 1847–1914, Edinburgh University Press (1968), pp. 90–91.

- ^ Camara, Alhaji Sait, [in] Sunu Chossan formerly Chossani Senegambia (history of Senegambia). GRTS Programs.

- ^ It can mean either "heart" or "honour" depending on the context.

- ^ Gravrand, Pangool, p. 40.

- ^ (in French) Gravrand, Henry : "L'Heritage spirituel Sereer : Valeur Traditionnelle d'hier, d'aujourd'hui et de demain" [in] Ethiopiques, numéro 31, révue socialiste de culture négro-africaine, 3e trimestre 1982 (Retrieved : 10 May 2012).

Bibliography

[edit]- Thiaw, Issa Laye, Myth de la Creation du monde selon les sages Seereer. p. 45

- Dion, Salif, L'Education traditionnelle à travers les chants et poèmes sereer, Dakar, Université de Dakar, 1983, p. 344

- Gravrand, Henry, La civilisation sereer, vol. II : Pangool, Nouvelles éditions africaines, Dakar, 1990, pp. 9–77, ISBN 2-7236-1055-1

- Gravrand, Henry : "L'Heritage spirituel Sereer : Valeur Traditionnelle d'hier, d'aujourd'hui et de demain" [in] Ethiopiques, numéro 31, révue socialiste de culture négro-africaine, 3e trimestre 1982

- Faye, Louis Diène, Mort et Naissance le monde Sereer, Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines, 1983, pp. 9–44, ISBN 2-7236-0868-9

- Kellog, Day Otis & Smith, William Robertson, The Encyclopædia Britannica: latest edition. A dictionary of arts, sciences and general literature, Volume 25, p. 64. Published by Werner, 1902.

- Thiaw, Issa Laye, La religiosité des Seereer, avant et pendant leur islamisation, in Éthiopiques, no. 54, volume 7, 2e semestre 1991

- Galvan, Dennis Charles, The State Must Be Our Master of Fire: How Peasants Craft Culturally Sustainable Development in Senegal. Berkeley, University of California Press, 2004, pp. 108–304, ISBN 0-520-23591-6

- Fondation Léopold Sédar Senghor. Éthiopiques, Issues 55–56. 1991. pp. 62–95

- Gastellu, Jean-Marc (with ref to notes of : M. Sambe – 1937), L'égalitarisme économique des Serer du Sénégal, IRD Editions, 1981. p. 130. ISBN 2-7099-0591-4

- Gravrand, Henry, La civilisation sereer, vol. I : Cosaan: les origines, Nouvelles éditions africaines, Dakar, 1983

- Sarr, Alioune, Histoire du Sine-Saloum (introduction, bibliographie et notes par Charles Becker), [in] Bulletin de l'IFAN, tome 46, série B, nos 3–4, 1986–1987 pp. 31–38

- Niang, Mor Sadio, IFAN. Ethiopiques numéro 31 révue socialiste de culture négro-africaine 3e trimestre 1982.

- Seck, A., Sow, I., & Niass, M., Senegal, [in] The biodiversity of traditional leafy vegetables, p. 85–110.

- Bressers, Hans & Rosenbaum, Walter A., Achieving sustainable development: the challenge of governance across social scales, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, p. 151, ISBN 0-275-97802-8. 18.

- Thiaw, Issa Laye, La femme Seereer (Sénégal), L'Harmattan, Paris, septembre 2005, p. 169, ISBN 2-7475-8907-2

- LA PIAILLÉE No. 141. avril 2006. Dakar

- Dupire, Marguerite, Les "tombes de chiens : mythologies de la mort en pays Serer (Sénégal), Journal of Religion in Africa, 1985, vol. 15, fasc. 3, pp. 201–215

- Dupire, Marguerite, "Sagesse sereer: Essais sur la pensée sereer ndut", KARTHALA Editions (1994), p. 54,ISBN 2865374874

- Kalis, Simone, Médecine Traditionnelle, Religion et Divination Chez les Seereer Siin du Sénégal, La Coonaissance de la Nuit. L'Harmattan, 1997, pp. 25–60, ISBN 2-7384-5196-9

- Biblical Archaeology Society. Bible review, Volumes 18–19. Published by: Biblical Archaeology Society, 2002.ISBN 0-9677901-0-7

- Wade, Amadou, Chronique du Walo sénégalais (1186-1855). B. Cissé trans. V. Monteil. Bulletin de l'IFAN, Series B, Vol. 26, no. 3/4. 1941, 1964

- Diouf, Niokhobaye, Chronique du royaume du Sine, (suivie de Notes sur les traditions orales et les sources écrites concernant le royaume du Sine par Charles Becker et Victor Martin (1972)), Bulletin de l'IFAN, tome 34, série B, no. 4, 1972, pp. 706–7 (pp. 4–5), pp. 713–14 (pp. 9–10)

- Krzyżaniak, Lech; Kroeper, Karla & Kobusiewicz, Michał, Muzeum Archeologiczne w Poznaniu. Interregional contacts in the later prehistory of northeastern Africa. Poznań Archaeological Museum, 1996, pp. 57–58,ISBN 83-900434-7-5

- Diop, Cheikh Anta, The African origin of civilization: myth or reality, L. Hill, 1974, pp. 9, 197, ISBN 1-55652-072-7

- American Society of African Culture. African forum, Volumes 3–4. American Society of African Culture., 1967. p. 85

- Ndiaye, Ousmane Sémou, Diversite et unicite Sereres: L'exemple de la Region de Thies. Ethiopiques n° 54, revue semestrielle de culture négro-africaine, Nouvelle série, volume 7 2e semestre 1991

- Becker, Charles: Vestiges historiques, trémoins matériels du passé clans les pays sereer, Dakar. 1993. CNRS - ORS TO M

- Madiya, Clémentine Faïk-Nzuji, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Canadian Centre for Folk Culture Studies, International Centre for African Language, Literature and Tradition (Louvain, Belgium), Tracing memory: a glossary of graphic signs and symbols in African art and culture. Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1996. pp. 5–115, ISBN 0-660-15965-1

- Berg, Elizabeth L., & Wan, Ruth, Cultures of the World: Senegal, Benchmark Books (NY), 2009, p. 144, ISBN 978-0-7614-4481-7

- Conversion to Islam: Military Recruitment and Generational Conflict in a Sereer-Safin Village (Bandia)

- Klein, Martin A, Islam and Imperialism in Senegal Sine-Saloum, 1847-1914, Edinburgh at the University Press (1968)