The Family Shakespeare

The Family Shakespeare (at times titled The Family Shakspeare) is a collection of expurgated Shakespeare plays, edited by Thomas Bowdler and his sister Henrietta ("Harriet"), intended to remove any material deemed too racy, blasphemous, or otherwise sensitive for young or female audiences, with the ultimate goal of creating a family-friendly rendition of Shakespeare's plays.[1] The Family Shakespeare is one of the most often cited examples of literary censorship, despite (or perhaps because of) its original family-friendly intentions.[2] The Bowdler name is also the origin of the term "bowdlerise",[1] meaning to omit parts of a work on moral grounds.[2]

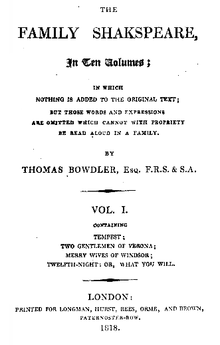

The first edition of The Family Shakespeare was published in 1807 in four duodecimo volumes, covering 20 plays.[3] In 1818 a second edition was published, containing all 36 available plays in 10 volumes.[4]

Precedents

[edit]The Bowdlers were not the first to undertake such a project, but their commitment to not augmenting or adding to Shakespeare's text, instead only removing sensitive material while striving to make as little of an impact as possible on the overall narrative of the play, differentiated The Family Shakespeare from the works of earlier editors. A Folger collection second folio (1632) went under the pen of a censor for the Holy Office in Spain, Guillermo Sanchez, who, similar to the Bowdlers, focused on redacting sensitive material; however, unlike the Bowdlers, he blacked out and redacted large swaths of Shakespeare's verses with little care for maintaining the integrity of the works, even going so far as to cut Measure for Measure out entirely.[5] Others took more creative liberty in sanitising the Bard's works: In 1681, Nahum Tate as Poet Laureate rewrote the tragedy of King Lear with a happy ending.[6] In 1807, Charles Lamb and Mary Lamb published a children's edition of the bard's work, Tales from Shakespeare, that had synopses of 20 plays but seldom quoted the original text.[7]

Motivation

[edit]As stated in the preface to the first edition, when the Bowdlers were children their father often entertained the family with readings from Shakespeare.[8] They later realised that their father had been omitting or altering passages he felt unsuitable for the ears of his wife and children:

In the perfection of reading few men were equal to my father; and such was his good taste, his delicacy, and his prompt discretion, that his family listened with delight to Lear, Hamlet, and Othello, without knowing that those matchless tragedies contained words and expressions improper to be pronounced; and without reason to suspect that any parts of the plays had been omitted by the circumspect and judicious reader.[9]

The Bowdlers took inspiration from their father's editing, feeling that it would be worthwhile to publish an edition which might be used in a family whose father was not a sufficiently "circumspect and judicious reader" to accomplish this expurgation himself, while still remaining as true to the original text as possible.[9]

Harriet Bowdler and the first edition

[edit]Despite the fact that Thomas' name was ultimately the sole listed author on all later editions, the 1807 first edition (which appeared anonymously) was in fact largely the work of his sister, Harriet.[10][11] This omission of authorship was likely because a woman could not then publicly admit that she was capable of such editing and compilation, much less that she understood Shakespeare's racy verses.[2] It took nearly two centuries for Harriet to receive due credit for her work.[1]

Harriet's first edition, containing 20 edited plays, was published at Bath in four small duodecimo volumes.[12] In the preface, Harriet describes her editorial goal as to endeavour "to remove every thing that could give just offence to the religious and virtuous mind", and to omit "many speeches in which Shakespeare has been tempted to 'purchase laughter at the price of decency.'"[8] In this manner, she says, she will produce a publication that can "be placed in the hands of young persons of both sexes".[8] However, in Harriet's edition she occasionally went beyond this "religious and virtuous" mission: in addition to the primary excisions of sexual material or Roman Catholic references that might prove unfavorable for good Protestants, Harriet also edited out scenes that she felt were trivial or uninteresting.[12] These excisions amounted to approximately 10% of the original text.[2] The edition was not particularly successful.[13]

Thomas Bowdler takes over

[edit]After the first edition, Thomas Bowdler managed to negotiate for the publication of a new version of The Family Shakespeare.[13] He took over from his sister and expanded the expurgations to the 16 remaining plays not covered by the first, on top of re-editing the 20 plays of the previous edition.[13] Excluded from this completed edition was Pericles, Prince of Tyre, perhaps due to the contention over its authorship or its virtual disappearance until 1854.[14] Thomas defended his expurgations on the title page, re-titling the work The Family Shakspeare: In which nothing is added to the original text, but those words and expressions are omitted which cannot with propriety be read in a family.[11] With this mission, Thomas Bowdler aimed to produce an edition of the works of "our immoral Bard", as Bowdler calls Shakespeare in the preface to the second edition, that would be appropriate for all ages, not to mention genders.[15] In addition to the reworkings and a new preface, Thomas also included introductory notes for a few of the plays—Henry IV, Othello, and Measure for Measure—to describe the advanced difficulty associated with editing them.[10]

The spelling "Shakspeare", used by Thomas Bowdler in the second edition but not by Harriet in the first, was changed in later editions (from 1847 on) to "Shakespeare", reflecting changes in the standard spelling of Shakespeare's name.[4]

Contents

[edit]The 20 plays of the first edition, selected, edited, and compiled in 4 volumes largely by Harriet Bowdler, occur in the order below:

The Tempest; A Midsummer Night's Dream; Much Ado About Nothing; As You Like It; The Merchant of Venice; Twelfth Night; The Winter's Tale; King John; Richard II; Henry IV, Part 1; Henry IV, Part 2; Henry V; Richard III; Henry VIII; Julius Caesar; Macbeth; Cymbeline; King Lear; Hamlet; Othello.

This edition, commandeered by Thomas rather than his sister,[11] contained all 36 available plays in 10 volumes.[4] Beyond adding 16 new plays, Thomas also re-edited the 20 plays previously expurgated by his sister, and reinserted the scenes that she had removed not for their inappropriate content but because she considered them trivial or uninteresting.[13][12] Not included is Pericles, Prince of Tyre, perhaps due to the contention over its authorship or its virtual disappearance until 1854.[14] The 36 plays of the second edition occur in the order below. New plays that did not previously appear in the 1807 first edition are marked with an asterisk:

The Tempest; The Two Gentlemen of Verona *; The Merry Wives of Windsor *; Twelfth Night; Measure For Measure *; Much Ado About Nothing; A Midsummer Night's Dream; Love's Labour's Lost *; The Merchant of Venice; As You Like It; All's Well That Ends Well *; The Taming of the Shrew *; The Winter's Tale; The Comedy of Errors *; Macbeth; King John; Richard II; Henry IV, Part 1; Henry IV, Part 2; Henry V; Henry VI, Part 1 *; Henry VI, Part 2 *; Henry VI, Part 3 *; Richard III; Henry VIII; Troilus and Cressida *; Timon of Athens *; Coriolanus *; Julius Caesar; Antony and Cleopatra *; Cymbeline; Titus Andronicus *; King Lear; Romeo and Juliet *; Hamlet; Othello.

Examples of Bowdler's edits

[edit]Some examples of alterations made by Thomas Bowdler within his 1818 complete edition of The Family Shakespeare are listed below, along with Bowdler's reasoning where a preface to the play is available.

Othello

[edit]In his preface to Othello, Bowdler commends the tragedy as "one of the noblest efforts of dramatic genius that has appeared in any age or in any language"; however, "the subject is unfortunately little suited to family reading."[16] He concedes the difficulty of adapting Othello for a family audience due to "the arguments which are urged" and themes of adultery, which are so intrinsic to the play itself that they cannot be removed without fundamentally changing the characters or plot and, "in fact, destroying the tragedy".[16] He ultimately comes to the conclusion that perhaps the dire anti-adultery warnings of the play are worth the raciness of some, but not all, of the passages, deciding to strive to maintain the moral message of the play instead of expurgating everything for the sake of family friendliness.[16] Indeed, at the conclusion of the preface, Bowdler recommends that "if, after all that I have omitted, it shall still be thought that this inimitable tragedy is not sufficiently correct for family reading, I would advise the transferring it from the parlour to the cabinet, where the perusal will not only delight the poetic taste, but convey useful and important instruction both to the heart and the understanding of the reader."[16]

| Original | Bowdlerised |

|---|---|

"Even now, now, very now, an old black ram |

Omitted |

| "I am one, sir, that comes to tell you, your daughter and the Moor are now making the beast with two backs." – (

Iago, I.1.121 |

"Your daughter and the Moor are now together." |

Measure for Measure

[edit]For the play's first Family Shakespeare appearance in the 1818 second edition, the entry is actually a reprint of John Philip Kemble's amended edition of Measure for Measure.[17] Kemble had edited the comedy for performance at the Theatre Royal in Covent Garden around 1803.[10] As stated by Bowdler in the 1818 preface to Measure for Measure, he chose to use the Kemble text over creating his own version, for the play proved too difficult to expurgate without fundamentally changing it in some way.[17][10] Bowdler soon rose to the challenge, though, and the next edition (1820) saw the publication of his own fully revised version.[10]

Bowdler lauds this comedy as "contain[ing] scenes which are truly of the first of dramatic poets", but also suggests that the story, with its wealth of "wickedness", is "little suited to a comedy".[17] He bemoans the boldness with which characters commit these "crimes" and the fact that they suffer no punishment for their doings; rather, states Bowdler, the women of the story gravitate to the men who have been, as they describe it, "a little bad".[17] Aside from this romanticising of immorality, Bowdler also bemoans the issue that "the indecent expressions with which many of the scenes abound, are so interwoven with the story, that it is extremely difficult to separate the one from the other", quite similar to his issues with editing Othello.[17]

Romeo and Juliet

[edit]Bowdler does not include a preface to Romeo and Juliet, but in general the targets of the expurgations are innuendos:

| Original | Bowdlerised |

|---|---|

| "the bawdy hand of the dial is now upon the prick of noon." – Mercutio, II.4.61 | "the hand of the dial is now upon the point of noon." |

| "Tis true, and therefore women being the weaker vessel are ever thrust to the wall ..." – Sampson, I.1.13 | Omitted |

| "not ope her legs to saint-seducing gold" – Romeo, I.1.206 | Omitted |

| "Spread thy close curtain, love performing night" – Juliet, III.2.5 | "... and come civil night" |

Titus Andronicus

[edit]Titus also lacks an introductory essay, but innuendos are once again the main excision. Bowdler removes some of the allusions to rape throughout the play, but does not entirely remove the many mentions and suggestions of the act.

| Original | Bowdlerised |

|---|---|

| "Villain, I have done thy mother." – Aaron, IV.2.76 | Omitted |

"There speak and strike, brave boys, and take your turns, |

"There speak, and strike, shadow'd from heaven's eye, |

Macbeth

[edit]Prominent modern literary figures such as Michiko Kakutani (in The New York Times) and William Safire (in his book, How Not to Write) have accused Bowdler of changing Lady Macbeth's famous "Out, damned spot!" line in Macbeth (V.1.38) to "Out, crimson spot!",[18][19][20] but Bowdler did not do that.[21] Thomas Bulfinch and Stephen Bulfinch did, however, in their 1865 edition of Shakespeare's works.[22]

Hamlet

[edit]In Bowdler's Hamlet the excisions are primarily on the grounds of blasphemy, removing all exclamations and curses that are religious in nature. There are also the usual redactions of sexual remarks and innuendos.

| Original | Bowdlerised |

|---|---|

| "For God's love, let me hear." – Hamlet, I.2.195 | "For Heaven's love, let me hear." |

"To those of mine! |

"To those of mine |

| III.2.102–113

Hamlet: here's metal more attractive. |

Hamlet: here's metal more attractive. [Lying at OPHELIA'S Feet.] |

Initial reception

[edit]The release of Harriet's first edition of The Family Shakespeare passed rather innocuously, not attracting much attention.[13][12][23] There were three reviews: one in favor, complimenting the tastefulness of such a "castrated" version; one against, decrying the edits as wholly unnecessary; and a third, in which the reviewer suggested that the only satisfactory edition of Shakespeare would be a folio of blank pages.[23]

At first, Thomas Bowdler's new and complete second edition seemed to be on the same track.[13][12] However, between 1821 and 1822 The Family Shakespeare found itself in the middle of a dispute between Blackwood's Magazine and the Edinburgh Review, the leading literary journals at the time.[13][23] While Blackwood's scorned Bowdler's work as "prudery in pasteboard", the Edinburgh commended his expurgations as saving readers from "awkwardness" and "distress".[24][13] It appears that the public sided with the Edinburgh. With this free publicity via controversy, interest in the book spiked and sales of The Family Shakespeare soared, with new editions consistently published every few years through the 1880s.[24][13]

In 1894 the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne declared that "More nauseous and more foolish cant was never chattered than that which would deride the memory or depreciate the merits of Bowdler. No man ever did better service to Shakespeare than the man who made it possible to put him into the hands of intelligent and imaginative children."[25] Indeed, this favorable opinion of Bowdler's expurgations was the conventional view at the time, as reflected by the increasing popularity and immense success of expurgated or Bowdlerized works: in 1850 there were 7 rival expurgated Shakespeares, and by 1900 there were almost 50.[23]

Downfall and legacy

[edit]The Bowdler name took on a life of its own soon after the publication of the 1818 second edition: by the mid 1820s, around the time of Thomas Bowdler's death, it had already become a verb, "to bowdlerize", meaning to remove sensitive or inappropriate material from a text.[2] However, at this time it was not yet a byword for literary censorship; rather, it was more of a genre of books edited to be appropriate for young readers or for families, and a very popular and successful genre at that.[23]

The tides began to change for the Bowdler name in 1916, when the writer Richard Whiteing decried the sanitized edition in an article for The English Review entitled "Bowdler Bowdlerised".[23][26] In the scathing and oft-sarcastic piece, Whiteing utterly denounces Bowdler and his expurgations, calling the changes "inconsistent" and scorning the prefaces to the more difficult-to-edit plays as "mealy-mouthed attempts to right himself".[26] The inconsistencies in what Bowdler changed versus what remained deeply perturbed Whiteing, who declares that "There is no end to it, except the in the limits of human patience."[26] He continues to liken Bowdler's perceived editorial tactlessness to "a baby playing with a pair of shears".[26] Whiteing argues that children should not be protected from the scandal of Shakespeare; no, they must be taught how to meet these facts of life.[26] He concludes his heated review with a warning, that Bowdlerization could easily become overzealous and create an even larger Index of banned literature than that of the Catholic Church at its prime, and a question: "Should there be any age of innocence?"[11][26]

It appears that the public was wont to agree with this strongly worded viewpoint. Public favor turned against Bowdlerized editions of books and expurgation for the sake of "appropriateness", and The Family Shakespeare began to be cited as an example of negative literary censorship.[23] The word "bowdlerize" lost its family-friendly connotations and instead became a term of derision.[27] This phenomenon is outlined in a piece in The Nation, written shortly after and in reaction to Whiteing's harsh commentary.[27] Taking a much more moderate stance than Whiteing, the opinion of whom The National describes as "flagrant exaggeration", they instead suggest that The Family Shakespeare is a relic of a bygone, pre-Victorian time, and that "As public taste moved on towards broader standards of literary propriety, the verb 'to bowdlerize' suffered corresponding degradation."[27] Nonetheless, they acknowledge that public opinion of Bowdler and bowdlerization as a practice is perhaps best represented by Whiteing's strong views.[27] By 1925 The Family Shakespeare was all but obsolete.[23]

In 1969 Noel Perrin published Dr. Bowdler's Legacy: A History of Expurgated Books in England and America. Perrin attributes the fall of bowdlerization and literary expurgation to the rise of Freudian psychology, feminism, and the influence of mass media.[28][23] Perrin also cites Whiteing's statements as a harbinger of doom for Bowdler's popular status.

On Bowdler's birthday each year (11 July), some literature fans and librarians "celebrate" Bowdler's "meddlings" on "Bowdler's Day".[2] The "celebration" is ironic, scorning Bowdler as a literary censor and perpetuating the views that Whiteing served to popularize.[2][29]

Editions of The Family Shakespeare continue to be published, printed, and read today, largely to observe what exactly Bowdler removed and why.[23]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Huang, Alexa (2 June 2016). "'Censure me in your wisdom': Bowdlerized Shakespeare in the nineteenth century". Index on Censorship. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eschner, Kat. "The Bowdlers Wanted to Clean Up Shakespeare, Not Become a Byword for Censorship". SmartNews. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ a b Bowdler, Harriet; Bowdler, Thomas, eds. (1807). The Family Shakespeare (1st ed.). London: J. Hatchard.

- ^ a b c d Bowdler, Thomas, ed. (1818–1820). The Family Shakspeare: in which nothing is added to the original text, but those words and expressions are omitted which cannot with propriety be read in a family (2nd ed.). London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown.

- ^ "Censoring Shakespeare". Folger Education. 24 September 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Massai, Sonia (2000). "Nahum Tate's Revision of Shakespeare's King Lears". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 40 (3): 435–450. doi:10.1353/sel.2000.0027. JSTOR 1556255. S2CID 201761270.

- ^ Lamb, Charles; Lamb, Mary (1807). Tales from Shakespeare.

- ^ a b c Shakespeare, William (1807). "Preface". The Family Shakespeare (First ed.). Bath, London: Hatchard. hdl:2027/njp.32101013492051.

- ^ a b Brown, Arthur (1965). Nicoll, Allardyce (ed.). The Great Variety of Readers (18 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-521-52354-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Kitzes, Adam H. (2013). "The Hazards of Expurgation: Adapting Measure for Measure to the Bowdler Family Shakespeare". Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies. 13 (2): 43–68. doi:10.1353/jem.2013.0010. JSTOR 43857923. S2CID 159311083.

- ^ a b c d Jones, Derek, ed. (2001). Censorship: A World Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-1-136-79864-1.

- ^ a b c d e "Bowdler, Henrietta Maria [Harriet] (1750–1830), writer and literary editor". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3028. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Thomas Bowdler". The First Amendment Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ a b "The Continual Riddle of Shakespeare's Pericles". The New Yorker. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ Shakespeare, William; Bowdler, Thomas (1818). The Family Shakspeare. Works.1818. Vol. 1 (Second ed.). London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. hdl:2027/nyp.33433074972302.

- ^ a b c d Shakespeare, William; Bowdler, Thomas (1818). The Family Shakspeare. Works.1818. Vol. 10 (Second ed.). London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown. hdl:2027/nyp.33433074972393.

- ^ a b c d e Shakespeare, William; Bowdler, Thomas (1818). The Family Shakspeare. Works.1818. Vol. 2 (Second ed.). London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown. hdl:2027/nyp.33433074972310.

- ^ Michiko Kakutani (January 7, 2011). "Light Out, Huck, They Still Want to Sivilize You". The New York Times. C1 & 5. (Only the original print version still contains Kakutani's accusation; the online version has been corrected.)

- ^ William Safire (2005) [1st pub. 1990]. How Not to Write. p. 100.

- ^ Davies, Ross E. (9 February 2011). "Gray Lady Bowdler: The Continuing Saga of the Crimson Spot". The Green Bag Almanac and Reader: 563–574. SSRN 1758989.

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1818). Bowdler, Thomas (ed.). The Family Shakspeare. Works.1818. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown. hdl:2027/nyp.33433074972336.

- ^ Davies, Ross E. (27 January 2009). "How Not to Bowdlerize". The Green Bag Almanac and Reader: 235–240. SSRN 1333764.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Green, Jonathon; Karolides, Nicholas J. (14 May 2014). Encyclopedia of Censorship. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1001-1.

- ^ a b Jack, Belinda (17 July 2012). The Woman Reader. Yale University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-300-12045-5.

blackwood's magazine and the edinburgh review the family shakespeare.

- ^ Swinburne, Algernon Charles (1894). "Social Verse". Studies in Prose and Poetry. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 84–109, 88–89. ISBN 9780836973310.

- ^ a b c d e f Whiteing, Richard (August 1916). "Bowdler Bowdlerised". The English review. pp. 100–111. ProQuest 2436784.

- ^ a b c d The Nation. Vol. 102. Nation Associates. 1916. p. 612.

- ^ Perrin, Noel (1969). Dr. Bowdler's Legacy: A History of Expurgated Books in England and America. New York: Atheneum. ASIN B001KT86IS. ERIC ED035635.

- ^ Vanderlin, Scott (10 July 2015). "Bowdler's Day". IIT Chicago-Kent Law Library. Retrieved 12 December 2018.