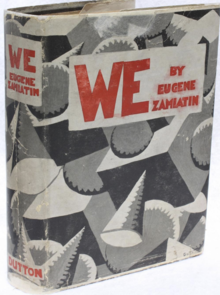

We (novel)

First edition of the novel (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1924) | |

| Author | Yevgeny Zamyatin |

|---|---|

| Original title | Мы |

| Translator | Various (list) |

| Cover artist | George Petrusov, Caricature of Aleksander Rodchenko (1933–1934) |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Dystopian novel, science fiction |

| Publisher | E. P. Dutton |

| Publication place | Soviet Russia / United States |

Published in English | 1924 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 226 pages 62,579 words |

| ISBN | 0-14-018585-2 |

| OCLC | 27105637 |

| 891.73/42 20 | |

| LC Class | PG3476.Z34 M913 1993 |

We (Russian: Мы, romanized: My) is a dystopian novel by Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin (often anglicised as Eugene Zamiatin) that was written in 1920–1921.[1] It was first published as an English translation by Gregory Zilboorg in 1924 by E. P. Dutton in New York, with the original Russian text first published in 1952. The novel describes a world of harmony and conformity within a united totalitarian state that is rebelled against by the protagonist, D-503 (Russian: Д-503). It influenced the emergence of dystopia as a literary genre. George Orwell said that Aldous Huxley's 1931 Brave New World must be partly derived from We,[2] although Huxley denied this. Orwell's own Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) was also inspired by We.[3]

Setting

[edit]We is set in the far future. D-503, a spacecraft engineer, lives in the One State,[4] an urban nation constructed almost entirely of glass (presumably to assist with mass surveillance.) The structure of the state is Panopticon-like, and life is based upon F. W. Taylor's principles of scientific management. Society is run centrally by a central power known as the Benefactor, and is run according to a strict timetable - people march in step with each other and are uniformed. There is no way of referring to people except by their given designations (referred to as 'numbers' in the novel.) The society in which We is set uses mathematical logic and reason for its scheduling and as justification for its actions.[5][6] The individual's behaviour is based on logic by way of formulae and equations outlined by the One State.[7]

Plot

[edit]A few hundred years after the One State's conquest of the entire world, the spaceship INTEGRAL is being built in order to invade and conquer extraterrestrial planets. The project's chief engineer, D-503, begins a journal that he intends to be carried upon the completed spaceship. The book is this journal—it titles chapters as '[n]th Entry' and begins each entry with three lines of notes summarising the events therein.

Like all other citizens of the One State, D-503 lives in a glass apartment building and is carefully watched by the secret police, or Bureau of Guardians. D-503's lover, O-90, has been assigned by the One State to visit him on certain nights. She is considered too short to bear children and is deeply grieved by that status. O-90's other lover and D-503's best friend is R-13, a State poet who reads his verse at public executions.

While on an assigned walk with O-90, D-503 meets a woman named I-330. I-330 smokes cigarettes, drinks alcohol and shamelessly flirts with D-503 instead of applying for an impersonal sex visit; all of these are illegal according to the laws of the One State.

Repelled and fascinated, D-503 struggles to overcome his attraction to I-330. She invites him to visit the Ancient House, notable for being the only opaque building in the One State, except for windows. Objects of aesthetic and historical importance dug up from around the city are stored there. There, I-330 offers him the services of a corrupt doctor to explain his absence from work. Leaving in horror, D-503 vows to denounce her to the Bureau of Guardians but finds that he cannot.

D-503 begins to have dreams, which disturb him, as dreams are thought to be a symptom of mental illness. Slowly, I-330 reveals to D-503 that she is involved with the Mephi, an organization plotting to bring down the One State. She takes him through secret tunnels inside the Ancient House to the world outside the Green Wall, which surrounds the city-state. There, D-503 meets the inhabitants of the outside world: humans whose bodies are covered with animal fur. The aims of the Mephi are to destroy the Green Wall and reunite the citizens of the One State with the outside world.

Despite the recent rift between them, O-90 pleads with D-503 to impregnate her illegally. After O-90 insists that she will obey the law by turning over their child to be raised by the One State, D-503 obliges. During the pregnancy, O-90 realizes that she cannot bear to be parted from her baby. At D-503's request, I-330 arranges for O-90 to be smuggled outside the Green Wall.

In his last journal entry, D-503 indifferently relates that he has been forcibly tied to a table and subjected to the "Great Operation", which has recently been mandated for all citizens of the One State to prevent possible riots; having been psycho-surgically refashioned into a state of mechanical "reliability", they would now function as "tractors in human form".[8][9] This operation removes the imagination and emotions by targeting parts of the brain with X-rays. After this operation, D-503 willingly informed the Benefactor, the dictator of the One State, about the inner workings of the Mephi. I-330 is then brought to an interrogation chamber, and subjected to torture by suffocation; D-503 expresses surprise that even torture could not induce I-330 to denounce her comrades. Despite her refusal, I-330 and those arrested with her have been sentenced to death, "under the Benefactor's Machine".

The Mephi uprising gathers strength; parts of the Green Wall have been destroyed, birds are repopulating the city and people start committing acts of social rebellion. Although D-503 expresses hope that the Benefactor shall restore "reason", the novel ends with the One State's survival in doubt. I-330's mantra is that, just as there is no highest number, there can be no final revolution.

Major themes

[edit]Dystopian society

[edit]The dystopian society depicted in We is presided over by the Benefactor and is surrounded by a giant Green Wall to separate the citizens from primitive untamed nature.[10] All citizens are known as "numbers".[11] Every hour in one's life is directed by the "Table of Hours". The action of We is set at some time after the Two Hundred Years' War, which has wiped out all but "0.2 [20%] of the earth's population".[12] The war was over a rare substance only mentioned in the book through a metaphor; the substance was called "bread" as the "Christians gladiated over it"—as in Christians killed for sport in Roman gladiator games as a form of entertainment, "bread and circuses", suggesting a war that was meant to distract the population from a power grab by the government. The war only ended after the use of weapons of mass destruction, so that the One State is surrounded with a post-apocalyptic landscape.

Allusions and references

[edit]

Many of the names and numbers in We are allusions to the experiences of Zamyatin or to culture and literature. "Auditorium 112" refers to cell number 112, where Zamyatin was twice imprisoned and the name of S-4711 is a reference to the Eau de Cologne number 4711.[13][14] Zamyatin, who worked as a naval architect, refers to the specifications of the icebreaker St. Alexander Nevsky.[15]

The numbers [.. .] of the chief characters in WE are taken directly from the specifications of Zamyatin's favourite icebreaker, the Saint Alexander Nevsky, yard no. A/W 905, round tonnage 3300, where O–90 and I-330 appropriately divide the hapless D-503 [.. .] Yu-10 could easily derive from the Swan Hunter yard numbers of no fewer than three of Zamyatin's major icebreakers – 1012, 1020, 1021 [.. .]. R-13 can be found here too, as well as in the yard number of Sviatogor A/W 904.[16][17]

Many comparisons to The Bible exist in We. There are similarities between Genesis Chapters 1–4 and We, where the One State is considered Paradise, D-503 is Adam and I-330 is Eve. The snake in this piece is S-4711, who is described as having a bent and twisted form, with a "double-curved body"; he is a double agent. References to Mephistopheles (in the Mephi) are seen as allusions to Satan and his rebellion against Heaven in the Bible (Ezekiel 28:11–19; Isaiah 14:12–15).[18][19][20] The novel can be considered a criticism of organised religion given this interpretation.[21] Zamyatin, influenced by Fyodor Dostoyevsky's Notes from Underground and The Brothers Karamazov, made the novel a criticism of the excesses of a militantly atheistic society.[21][22] The novel displayed an indebtedness to H. G. Wells's dystopia When the Sleeper Wakes (1899).[23]

The novel uses mathematical concepts symbolically. The spaceship that D-503 is supervising the construction of is called the Integral, which he hopes will "integrate the grandiose cosmic equation". D-503 also mentions that he is profoundly disturbed by the concept of the square root of −1—which is the basis for imaginary numbers, imagination having been deprecated by the One State. Zamyatin's point, probably in light of the increasingly dogmatic Soviet government of the time, would seem to be that it is impossible to remove all the rebels against a system. Zamyatin even says this through I-330, "There is no final revolution. Revolutions are infinite".[24]

Literary significance and influences

[edit]Along with Jack London's The Iron Heel, We is generally considered to be the grandfather of the satirical futuristic dystopia genre. It takes the modern industrial society to an extreme conclusion, depicting a state that believes that free will is the cause of unhappiness, and that citizens' lives should be controlled with mathematical precision based on the system of industrial efficiency created by Frederick Winslow Taylor. The Soviet attempt at implementing Taylorism, led by Aleksei Gastev, may have immediately influenced Zamyatin's portrayal of the One State.[25] In Russia, a dystopian totalitarian society before Zamyatin was described by Mikhail Saltykov in his satirical novel The History of a Town, and Saltykov's idea of "Utopia of the straight line" continues in We: "To unbend the wild curve, to straighten it out to a tangent — to a straight line!"[26]

Christopher Collins in Evgenij Zamjatin: An Interpretive Study finds the many intriguing literary aspects of We more interesting and relevant today than the political aspects:

- An examination of myth and symbol reveals that the work may be better understood as an internal drama of a conflicted modern man rather than as a representation of external reality in a failed utopia. The city is laid out as a mandala, populated with archetypes and subject to an archetypal conflict. One wonders if Zamyatin were familiar with the theories of his contemporary C. G. Jung or whether it is a case here of the common European zeitgeist.

- Much of the cityscape and expressed ideas in the world of We are taken almost directly from the works of H. G. Wells, a popular apostle of scientific socialist utopia whose works Zamyatin had edited in Russian.

- In the use of color and other imagery Zamyatin shows he was influenced by Kandinsky and other European Expressionist painters.

The little-known Russian dystopian novel Love in the Fog of the Future, published in 1924 by Andrei Marsov, has also been compared to We.[27]

George Orwell claimed that Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932) must be partly derived from We.[28] However, in a letter to Christopher Collins in 1962, Huxley says that he wrote Brave New World as a reaction to H. G. Wells's utopias long before he had heard of We.[29]

Kurt Vonnegut said that in writing Player Piano (1952), he "cheerfully ripped off the plot of Brave New World, whose plot had been cheerfully ripped off from Yevgeny Zamyatin's We".[30] Ayn Rand's Anthem (1938) has many significant similarities to We (detailed here), although it is stylistically and thematically different.[31] Vladimir Nabokov's novel Invitation to a Beheading may suggest a dystopian society with some similarities to Zamyatin's; Nabokov read We while writing Invitation to a Beheading.[32]

Orwell began Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) some eight months after he read We in a French translation and wrote a review of it.[33] Orwell is reported as "saying that he was taking it as the model for his next novel".[34] Brown writes that for Orwell and certain others, We "appears to have been the crucial literary experience".[35] Shane states that "Zamyatin's influence on Orwell is beyond dispute".[36] Robert Russell, in an overview of the criticism of We, concludes that "1984 shares so many features with We that there can be no doubt about its general debt to it"; but that there is a minority of critics who view the similarities between We and Nineteen Eighty-Four as "entirely superficial". Further, Russell finds that "Orwell's novel is both bleaker and more topical than Zamyatin's, lacking entirely that ironic humour that pervades the Russian work".[29]

In The Right Stuff (1979), Tom Wolfe describes We as a "marvelously morose novel of the future" featuring an "omnipotent spaceship" called the Integral whose "designer is known only as 'D-503, Builder of the Integral'". Wolfe goes on to use the Integral as a metaphor for the Soviet launch vehicle, the Soviet space programme, or the Soviet Union.[37]

Jerome K. Jerome has been cited as an influence on Zamyatin's novel.[38] Jerome's short story The New Utopia (1891)[39] describes a regimented future city, indeed world, of nightmarish egalitarianism, where men and women are barely distinguishable in their grey uniforms (Zamyatin's "unifs") and all have short black hair, natural or dyed. No one has a name: women wear even numbers on their tunics, and men wear odd, just as in We. Equality is taken to such lengths that people with well-developed physiques are liable to have lopped limbs. In Zamyatin, similarly, the equalisation of noses is earnestly proposed. Jerome has anyone with an overactive imagination subjected to a levelling-down operation—something of central importance in We. There is a shared depiction by both Jerome and Zamyatin that individual and, by extension, familial love is a disruptive and humanizing force. Jerome's works were translated in Russia three times before 1917.[citation needed]

In 1998, the first English translation of Cursed Days, a diary kept in secret in 1918-20 by anti-communist Russian author Ivan Bunin during the Russian Civil War in Moscow and Odessa was published in Chicago. In a foreword, the diary's English translator, Thomas Gaiton Marullo, described Cursed Days as a rare example of dystopian nonfiction and pointed out multiple parallels between the secret diary kept by Bunin and the diary kept by D-503.[40]

Publication history

[edit]

Zamyatin's literary position deteriorated throughout the 1920s, and he was eventually allowed to emigrate to Paris in 1931, probably after the intercession of Maxim Gorky.

The novel was first published in English in 1924 by E. P. Dutton in New York in a translation by Gregory Zilboorg,[41] but its first publication in the Soviet Union had to wait until 1988,[42] when glasnost resulted in it appearing alongside George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. A year later, We and Brave New World were published together in a combined edition.[43]

In 1994, the novel received a Prometheus Award in the "Hall of Fame" category.[44]

Russian-language editions

[edit]- Zamiatin, Evgenii Ivanovich (1952). Мы. Niu-Iork: Izd-vo im. Chekhova. ISBN 978-5-7390-0346-1. (bibrec) (bibrec (in Russian))

- The first complete Russian-language edition of We was published in New York in 1952. (Brown, p. xiv, xxx)

- Zamiatin, Evgenii Ivanovich (1967). Мы (in Russian). vstupitel'naya stat'ya Evgenii Zhiglevich, stat'ya posleslovie Vladimira Bondarenko. New York: Inter-Language Literary Associates. ISBN 978-5-7390-0346-1.

- Zamiatin, Evgenii Ivanovich (1988). Selections (in Russian). sostaviteli T.V. Gromova, M.O. Chudakova, avtor stati M.O. Chudakova, kommentarii Evg. Barabanova. Moskva: Kniga. ISBN 978-5-212-00084-0. (bibrec) (bibrec (in Russian))

- We was first published in the USSR in this collection of Zamyatin's works. (Brown, p. xiv, xxx)

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny; Andrew Barratt (1998). Zamyatin: We. Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 978-1-85399-378-7. (also cited as Zamyatin: We, Duckworth, 2006) (in Russian and English)

- Edited with Introduction and Notes by Andrew Barratt. Plain Russian text, with English introduction, bibliography and notes.

Translations to English

[edit]- Zamiatin, Eugene (1924). We. Gregory Zilboorg (trans.). New York: Dutton. ISBN 978-0-88233-138-6. [2]

- Zamiatin, Eugene (1954). We. Gregory Zilboorg (trans.). New York: Dutton. ISBN 978-84-460-2672-3.

- Zamiatin, Evgenii Ivanovich (1960). "We". In Bernard Guilbert Guerney (ed.). An Anthology of Russian Literature in the Soviet Period from Gorki to Pasternak. Bernard Guilbert Guerney (trans.). New York: Random House. pp. 168–353. ISBN 978-0-39470-717-4.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (1970). We. Bernard Guilbert Guerney (trans.). London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 022461794X.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (1999) [1972]. We. Mirra Ginsburg (trans.). New York: Bantam. ISBN 978-0-552-67271-9.

- Zamyatin, Evgeny (1987). "We". In Carl Proffer (ed.). Russian Literature of the Twenties: An Anthology. S.D. Cioran (trans.). US: Ardis. pp. 3–139. ISBN 978-0-88233-821-7.

- Zamyatin, Evgeny (1991). We. Alex Miller (trans.). Moscow: Raduga. ISBN 978-5-05-004845-5.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (1993). We. Clarence Brown (trans.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-018585-0. (preview)

- Zamiatin, Eugene (2000). We. Gregory Zilboorg (trans.). US: Transaction Large Print. ISBN 978-1-56000-477-6. (author photo on cover)

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (2006). We. Natasha Randall (trans.). New York: Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-8129-7462-1.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (2009). We. Hugh Aplin (trans.). London: Hesperus Press. ISBN 978-1843914464.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (2019). We. Kirsten Lodge (trans.). Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press. ISBN 9781554814107.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (2020). We. Nadja Boltyanskaya (trans.). London: Independently published. ISBN 979-8642770139.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (2021). We. Bela Shayevich (trans.). New York: Ecco (A division of Harper Collins). ISBN 978-0063068445.

Translations to other languages

[edit]- Zamjatin, Jevgenij Ivanovič (1927). My (in Czech). Václav Koenig (trans.). Prague (Praha): Štorch-Marien. [3]

- Zamâtin, Evgenij Ivanovic (1929). Nous autres (in French). B. Cauvet-Duhamel (trans.). Paris: Gallimard. [4]

- Zamjàtin, Evgenij (1955). Noi (in Italian). Ettore Lo Gatto (trans.). Bergamo (Italy): Minerva Italica.

- Samjatin, Jewgenij (1958). Wir. Roman (in German). Gisela Drohla (trans.). Cologne (Köln) (Germany): Kiepenheuer & Witsch. ISBN 3-462-01607-5.

- Замјатин, Јевгениј (1969). Ми (in Serbian). Мира Лалић (trans.). Београд (Serbia): Просвета.

- Zamjatin, Jevgenij (1970). Wij (in Dutch). Dick Peet (trans.). Amsterdam (The Netherlands): De Arbeiderspers. ISBN 90-295-5790-7.

- Zamiatin, Yevgueni (1970). Nosotros (in Spanish). Juan Benusiglio Berndt (trans.). Barcelona (Spain): Plaza & Janés.

- Zamjatin, Evgenij Ivanovič (1975). Mi. Drago Bajt (trans.). Ljubljana (Slovenia): Cankarjeva založba.

- Zamyatin, Yevgenij (1988). BİZ (in Turkish). Füsun Tülek (trans.). İstanbul (Turkey): Ayrıntı.

- Zamiatin, Eugeniusz (1989). My (in Polish). Adam Pomorski (trans.). Warsaw (Poland): Alfa. ISBN 978-83-7001-293-9.

- Zamjàtin, Evgenij (1990). Noi (in Italian). Ettore Lo Gatto (trans.). Milano (Italy): Feltrinelli. ISBN 978-88-07-80412-0.

- Zamjatin, Jevgeni (2006). Meie (in Estonian). Maiga Varik (trans.). Tallinn: Tänapäev. ISBN 978-9985-62-430-2.

- Zamjatyin, Jevgenyij (2008) [1990]. Mi (in Hungarian). Pál Földeák (trans.). Budapest (Hungary): Cartaphilus. ISBN 978-963-266-038-7.

- Zamiatine, Evgueni (1999). Nós (in Portuguese). Manuel João Gomes (trans.). Lisboa (Portugal): Antigona. ISBN 9789726080329.

- Zamiatin, Jevgenij (2009). Mes. Irena Potašenko (trans.). Vilnius (Lithuania): Kitos knygos. ISBN 9789955640936.

- Zamiatin, Yeuveni (2010). Nosotros. Julio Travieso (trad. y pról.). México: Lectorum. ISBN 9788446026723.

- Zamiatin, Yeuveni (2011). Nosotros. Alfredo Hermosillo y Valeria Artemyeva (trads.) Fernando Ángel Moreno (pról.). Madrid: Cátedra. ISBN 9788437628936.

- Samjatin, Evgenij (2013). Wir. Roman (in German). Josef Meinolf Opfermann (trans.). Bremen (Germany): Europäischer Literaturverlag. ISBN 978-3-86267-770-2.

- Zamjatin, Jevgenij (2015) [1959]. Vi (in Swedish). Sven Vallmark (trans.). Stockholm (Sweden): Modernista. ISBN 978-91-7645-209-7.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (2015). Nosaltres (in Catalan). Miquel Cabal Guarro (trans.). Catalunya: Les Males Herbes. ISBN 9788494310850.

- Zamjatin, Jevgenij (2016). Vi (in Norwegian Bokmål). Torgeir Bøhler (trans.). Norway: Solum. ISBN 9788256017867.

- Zamiátin, Ievguêni (2017). Nós (in Portuguese). Gabriela Soares (trans.). Brazil: Editora Aleph. ISBN 978-85-7657-311-1.

- Zamiatin, Evgenii (2017). Nós (in Galician). Lourenzo Maroño and Elena Sherevera (trans.). Galiza: Hugin e Munin. ISBN 978-84-946538-8-9.

- Zamiatine, Evgueni (2017). Nous (in French). Hélène Henry (trans.). Arles (France): Actes Sud. ISBN 978-2-330-07672-6.

- Zamjatin, Evgenij (2021). Noi (in Italian). Alessandro Cifariello (trans.). Italy: Fanucci. ISBN 978-88-347-4166-5.

Adaptations

[edit]Films

[edit]The German TV network ZDF adapted the novel for a TV movie in 1982, under the German title Wir (English: We).[45]

We is heavily referenced in the 2023 sci-fi feature film 1984.

The novel has also been adapted, by Alain Bourret, a French director, into a short film called The Glass Fortress (2016).[46] The Glass Fortress is an experimental film that employs a technique known as still image film, and is shot in black-and-white, which help support the grim atmosphere of the story's dystopian society.[47] The film is technically similar to La Jetée (1962), directed by Chris Marker, and refers somewhat to THX 1138 (1971), by George Lucas, in the "religious appearance of the Well Doer".[48] According to film critic Isabelle Arnaud, The Glass Fortress has a special atmosphere underlining a story of thwarted love that will be long remembered.[49]

A Russian film adaptation, directed by Hamlet Dulyan and starring Egor Koreshkov, initially planned for release in 2021,[50] was released in 2024.

Radio

[edit]A two-part adaptation by Sean O'Brien and directed by Jim Poyser was broadcast on 18 and 25 April 2004 on BBC Radio 4's Classic Serial.[51] The cast included Anton Lesser as D-503, Joanna Riding as I-330, Julia Routhwaite as O-90, Brigit Forsyth as U, Patrick Bridgeman as S and Don Warrington as R-13.

Theatre

[edit]The Montreal company Théâtre Deuxième Réalité produced an adaptation of the novel in 1996, adapted and directed by Alexandre Marine, under the title Nous Autres.[52]

Music

[edit]Released in 2015, The Glass Fortress[53] is a musical and narrative adaptation of the novel by Rémi Orts Project and Alan B.

In 2022, the Canadian indie rock band Arcade Fire released We, an album whose title was inspired by the novel.[54]

Other

[edit]In 2022, independent creator Doug Strain produced Beyond the Green Wall, a Dungeons and Dragons adventure based on the novel.

Legacy

[edit]We directly inspired:

- Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932)[55] (Disputed by Huxley, see above.)

- Vladimir Nabokov's Invitation to a Beheading (1935–1936)[citation needed]

- Ayn Rand's Anthem (1938)[56]

- George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)[3]

- Kurt Vonnegut's Player Piano (1952)[30]

- William F. Nolan & George Clayton Johnson's Logan's Run (1967)[citation needed]

- Ira Levin's This Perfect Day (1970)

- Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed (1974)[57]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Brown, p. xi, citing Shane, gives 1921. Russell, p. 3, dates the first draft to 1919.

- ^ Orwell, George (4 January 1946). "Review of WE by E. I. Zamyatin". Tribune. London – via Orwell.ru.

- ^ a b Bowker, Gordon (2003). Inside George Orwell: A Biography. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-312-23841-4.

- ^ The Ginsburg and Randall translations use the phrasing "One State". Guerney uses "The One State"—each word is capitalized. Brown uses the single word "OneState", which he calls "ugly" (p. xxv). Zilboorg uses "United State".

All of these are translations of the phrase Yedinoye Gosudarstvo (Russian: Единое Государство). - ^ George Orwell by Harold Bloom pg 54 Publisher: Chelsea House Pub ISBN 978-0791094280

- ^ Zamyatin's We: A Collection of Critical Essays by Gary Kern pgs 124, 150 Publisher: Ardis ISBN 978-0882338040

- ^ The Literary Underground: Writers and the Totalitarian Experience, 1900–1950 pgs 89–91 By John Hoyles Palgrave Macmillan; First edition (15 June 1991) ISBN 978-0-312-06183-8 [1]

- ^ Serdyukova, O.I. [О.И. Сердюкова] (2011). Проблема свободы личности в романе Э. Берджесса "Механический апельсин" [The problem of the individual freedom in E. Burgess’s novel "A Clockwork Orange"] (PDF). Вісник Харківського національного університету імені В. Н. Каразіна. Серія: Філологія [The Herald of the Karazin Kharkiv National University. Series: Philology] (in Russian). 936 (61). Kharkiv: 144–146. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Hughes, Jon (2006). Facing Modernity: Fragmentation, Culture and Identity in Joseph Roth's Writing in 1920s. London: Maney Publishing for the Modern Humanities Research Association. p. 127. ISBN 978-1904350378.

- ^ Ginsburg trans. This term is also translated as "Well-Doer".[citation needed] Benefactor translates Blagodetel (Russian: Благодетель).

- ^ Ginsburg trans. Numbers translates nomera (Russian: номера). This is translated by Natasha Randall as "cyphers" in the 2006 edition published by The Modern Library, New York.

- ^ Fifth Entry (Ginsburg translation, p. 21).

- ^ Randall, p. xvii.

- ^ Ermolaev.

- ^ Shane, p 12.

- ^ Myers.

- ^ "All these icebreakers were constructed in England, in Newcastle and yards nearby; there are traces of my work in every one of them, especially the Alexander Nevsky—now the Lenin; I did the preliminary design, and after that none of the vessel's drawings arrived in the workshop without having been checked and signed:

'Chief surveyor of Russian Icebreakers' Building E.Zamiatin." [The signature is written in English.] (Zamyatin ([1962])) - ^ "Ezekiel 28:11 - 28:19". www.kingjamesbibleonline.org. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ "Isaiah 14:12 - 14:15". www.kingjamesbibleonline.org. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey Burton. Mephistopheles: The devil in the modern world. Cornell University Press, 1990.

- ^ a b Gregg.

- ^ Constantin V. Ponomareff; Kenneth A. Bryson (2006). The Curve of the Sacred: An Exploration of Human Spirituality. Editions Rodopi BV. ISBN 978-90-420-2031-3.

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Utopianism. Rowman & Littlefield. 2017. p. 429.

- ^ Ginsburg, Introduction, p. v. The Thirtieth Entry has a similar passage.

- ^ "Alexei Gastev and the Soviet Controversy over Taylorism, 1918-24" (PDF). Soviet Studies, vol. XXIX, no. 3, July 1977, pp. 373-94. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ Peter Petro. Beyond History: a Study of Saltykov's The History of a Town. 1972

- ^ "Марсов, Андрей". Academic.ru. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Orwell (1946).

- ^ a b Russell, p. 13.

- ^ a b Staff (1973). "Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. Playboy Interview". Playboy Magazine Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gimpelevich, Zina (1997). "'We and 'I' in Zamyatin's We and Rand's Anthem". Germano-Slavica. 10 (1): 13–23.

- ^ M. Keith Booker, The Post-utopian Imagination: American Culture in the Long 1950s. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002 ISBN 0313321655, p. 50.

- ^ Orwell (1946). Russell, p. 13.

- ^ Bowker (p. 340) paraphrasing Rayner Heppenstall.

Bowker, Gordon (2003). Inside George Orwell: A Biography. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-23841-4. - ^ Brown trans., Introduction, p. xvi.

- ^ Shane, p. 140.

- ^ Wolfe, Tom (2001). The Right Stuff. Bantam. ISBN 978-0-553-38135-1. "D-503": p. 55, 236. "it looked hopeless to try to catch up with the mighty Integral in anything that involved flights in earth orbit.": p. 215. Wolfe uses the Integral in several other passages.

- ^ Stenbock-Fermor.

- ^ The New Utopia. Published in Diary of a Pilgrimage (and Six Essays).(full text)

- ^ Cursed Days, pages 23-24.

- ^ In a translation by Zilboorg,

- ^ Brown translation, p. xiv. Tall notes that glasnost resulted in many other literary classics being published in the USSR during 1988–1989.

- ^ Tall, footnote 1.

- ^ "Libertarian Futurist Society: Prometheus Awards". Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Wir at IMDb

- ^ The Glass Fortress on YouTube

- ^ Wittek, Louis (6 June 2016). "The Glass Fortress". SciFi4Ever.com. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Erlich, Richard D.; Dunn, Thomas P. (29 April 2016). "The Glass Fortress". ClockWorks2.org. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Arnaud, Isabelle (2018). "The Glass Fortress: Le court métrage". UnificationFrance.com (in French). Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ We at IMDb

- ^ "Classic Serial: We - Episode 1". BBC Programme Index. 18 April 2004. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Article on Théâtre Deuxième Réalité and its early productions: Dennis O'Sullivan (1995). "De la lointaine Sibérie: The Emigrants du Théâtre Deuxième Réalité" (PDF). Jeu: Revue de Théâtre (77). érudit.org: 121–125.

- ^ "Rémi Orts Project & Alan B – The Glass Fortress". Rémi Orts. 15 January 2015.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (5 May 2022). "Arcade Fire: We review – goodbye cod reggae, hello stadium singalongs". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ Blair E. 2007. Literary St. Petersburg: a guide to the city and its writers. Little Bookroom, p.75

- ^ Mayhew R, Milgram S. 2005. Essays on Ayn Rand's Anthem: Anthem in the Context of Related Literary Works. Lexington Books, p.134

- ^ Le Guin UK. 1989. The Language of the Night. Harper Perennial, p.218

Bibliography

- Reviews

- Sally Feller, Your Daily Dystopian History Lesson From Yevgeny Zamyatin: A Review of We

- Joshua Glenn (23 July 2006). "In a perfect world: Yevgeny Zamyatin's far-out science fiction dystopia, 'We,' showed the way for George Orwell and countless others". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 15 October 2006.

- Books

- Russell, Robert (1999). Zamiatin's We. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 978-1-85399-393-0.

- Shane, Alex M. (1968). The life and works of Evgenij Zamjatin. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 441082.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (1992). A Soviet Heretic: Essays. Mirra Ginsburg (editor and translator). Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-8101-1091-5.

- Collins, Christopher (1973). Evgenij Zamjatin: An Interpretive Study. The Hague: Mouton & Co.

- Journal articles

- Ermolaev, Herman; Edwards, T. R. N. (October 1982). "Review of Three Russian Writers and the Irrational: Zamyatin, Pil'nyak, and Bulgakov by T. R. N. Edwards". The Russian Review. 41 (4). Blackwell Publishing: 531–532. doi:10.2307/129905. JSTOR 129905.

- Fischer, Peter A.; Shane, Alex M. (Autumn 1971). "Review of The Life and Works of Evgenij Zamjatin by Alex M. Shane". Slavic and East European Journal. 15 (3). American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages: 388–390. doi:10.2307/306850. JSTOR 306850.

- Gregg, Richard A. (December 1965). "Two Adams and Eve in the Crystal Palace: Dostoevsky, the Bible, and We". Slavic Review. 24 (4). The American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies: 680–687. doi:10.2307/2492898. JSTOR 2492898. S2CID 164122563.

- Layton, Susan (February 1978). "The critique of technocracy in early Soviet literature: The responses of Zamyatin and Mayakovsky". Dialectical Anthropology. 3 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1007/BF00257387. S2CID 143937157.

- McCarthy, Patrick A. (July 1984). "Zamyatin and the Nightmare of Technology". Science-Fiction Studies. 11 (2): 122–29.

- McClintock, James I. (Autumn 1977). "United State Revisited: Pynchon and Zamiatin". Contemporary Literature. 18 (4). University of Wisconsin Press: 475–490. doi:10.2307/1208173. JSTOR 1208173.

- Myers, Alan (1993). "Zamiatin in Newcastle: The Green Wall and The Pink Ticket". The Slavonic and East European Review. 71 (3): 417–427. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- Myers, Alan. "Zamyatin in Newcastle". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007. (updates articles by Myers published in The Slavonic and East European Review)

- Stenbock-Fermor, Elizabeth; Zamiatin (April 1973). "A Neglected Source of Zamiatin's Novel "We"". Russian Review. 32 (2). Blackwell Publishing: 187–188. doi:10.2307/127682. JSTOR 127682.

- Struve, Gleb; Bulkakov, Mikhail; Ginsburg, Mirra; Glenny, Michael (July 1968). "The Re-Emergence of Mikhail Bulgakov". The Russian Review. 27 (3). Blackwell Publishing: 338–343. doi:10.2307/127262. JSTOR 127262.

- Tall, Emily (Summer 1990). "Behind the Scenes: How Ulysses was Finally Published in the Soviet Union". Slavic Review. 49 (2). The American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies: 183–199. doi:10.2307/2499479. JSTOR 2499479. S2CID 163819972.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (1962). "O moikh zhenakh, o ledokolakh i o Rossii". Mosty (in Russian). IX. Munich: Izd-vo Tsentralnogo obedineniia polit. emigrantov iz SSSR: 25.

- English: My wives, icebreakers and Russia. Russian: О моих женах, о ледоколах и о России.

- The original date and location of publication are unknown, although he mentions the 1928 rescue of the Nobile expedition by the Krasin, the renamed Svyatogor.

- The article is reprinted in E. I. Zamiatin, 'O moikh zhenakh, o ledokolakh i o Rossii', Sochineniia (Munich, 1970–1988, four vols.) II, pp. 234–40. (in Russian)

External links

[edit]- We at Standard Ebooks (1924 Zilboorg translation, in English)

- We at Project Gutenberg (1924 Zilboorg translation, in English)

- We - full text (in Russian)

- We - full text (1924 Zilboorg translation, in English)

We public domain audiobook at LibriVox

We public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Film - Wir (1982, GE) at IMDb

- 1924 Russian novels

- 1924 science fiction novels

- Book censorship in the Soviet Union

- Censored books

- Cosmism

- Dystopian novels

- Fiction with unreliable narrators

- Fictional astronauts

- Novels about totalitarianism

- Novels by Yevgeny Zamyatin

- Russian novels adapted into films

- Russian novels adapted into television shows

- Russian philosophical novels

- Russian science fiction novels

- Science fiction novels adapted into films

- Soviet novels

- Soviet science fiction novels