Virginia General Assembly

Virginia General Assembly | |

|---|---|

| 163rd Virginia General Assembly | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses | Senate House of Delegates |

Term limits | None |

| History | |

| Founded | July 30, 1619 |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

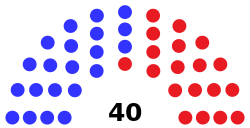

| Seats | 140 40 senators 100 delegates |

| |

Senate political groups |

|

| |

House of Delegates political groups |

|

Length of term | Senate: 4 years House of Delegates: 2 years |

| Elections | |

Last Senate election | November 7, 2023 |

Last House of Delegates election | November 7, 2023 |

| Redistricting | Commission of eight lawmakers and eight citizens |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Virginia State Capitol Richmond | |

| Website | |

| virginiageneralassembly | |

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, and the first elected legislative assembly in the New World. It was established on July 30, 1619.[1][2]

The General Assembly is a bicameral body consisting of a lower house, the Virginia House of Delegates, with 100 members, and an upper house, the Senate of Virginia, with 40 members. Senators serve terms of four years, and delegates serve two-year terms. Combined, the General Assembly consists of 140 elected representatives from an equal number of constituent districts across the commonwealth. The House of Delegates is presided over by the speaker of the House, while the Senate is presided over by the lieutenant governor of Virginia. The House and Senate each elect a clerk and sergeant-at-arms. The Senate of Virginia's clerk is known as the clerk of the Senate (instead of as the secretary of the Senate, the title used by the U.S. Senate).

Following the 2019 election, the Democratic Party held a majority of seats in both the House and the Senate for the first time since 1996. They were sworn into office on January 8, 2020, at the start of the 161st session.[3][4] In the 2021 election, the Republican Party recaptured a majority in the House of Delegates, then lost it after the 2023 election, when the Democratic Party secured majorities in both chambers of the General Assembly.

Capitol

[edit]The General Assembly meets in Virginia's capital of Richmond. When sitting in Richmond, the General Assembly holds sessions in the Virginia State Capitol, designed by Thomas Jefferson in 1788 and expanded in 1904. During the American Civil War, the building was used as the capitol of the Confederate States, housing the Confederate Congress. The building was renovated between 2005 and 2006. Senators and delegates have their offices in the General Assembly Building across the street directly north of the Capitol, which have been rebuilt and are expected to open in 2023.[5] The Governor of Virginia lives across the street directly east of the Capitol in the Virginia Executive Mansion.

History

[edit]The Virginia General Assembly is described as "the oldest continuous law-making body in the New World."[6] Its existence dates to its establishment at Jamestown on July 30, 1619, by instructions from the Virginia Company of London to the new Governor Sir George Yeardley. It was initially a unicameral body composed of the Company-appointed Governor and Council of State, plus 22 burgesses elected by the settlements and Jamestown.[7] The Assembly became bicameral in 1642 upon the formation of the House of Burgesses. The Assembly had a judicial function of hearing cases both original and appellate.[8] At various times it may have been referred to as the Grand Assembly of Virginia.[9] The General Assembly met in Jamestown from 1619 until 1699, when it first moved to the College of William & Mary near Williamsburg, Virginia, and from 1705 met in the colonial Capitol building. It became the General Assembly in 1776 with the ratification of the Virginia Constitution. The government was moved to Richmond in 1780 during the administration of Governor Thomas Jefferson.

Salary and qualifications

[edit]The annual salary for senators is $18,000.[10] The annual salary for delegates is $17,640, with the exception that the Speaker's salary is $36,321.[11] Members and one staff member also receive a per diem allowance for each day spent attending to official duties such as attending session in Richmond or attending committee meetings. Transportation expenses are reimbursed.[12]

Under the Constitution of Virginia, senators and delegates must be twenty-one years of age at the time of the election, residents of the district they represent, and qualified to vote for members of the General Assembly. Under the Constitution, "a senator or delegate who moves his residence from the district for which he is elected shall thereby vacate his office."[13]

The state constitution specifies that the General Assembly shall meet annually, and its regular session is a maximum of 60 days long in even-numbered years and 30 days long in odd-numbered years, unless extended by a two-thirds vote of both houses.[14] The Governor of Virginia may convene a special session of the General Assembly "when, in his opinion, the interest of the Commonwealth may require" and must convene a special session "upon the application of two-thirds of the members elected to each house."[15]

Redistricting reform

[edit]Article II, section 6 on apportionment states, "Members of the . . . Senate and of the House of Delegates of the General Assembly shall be elected from electoral districts established by the General Assembly. Every electoral district shall be composed of contiguous and compact territory and shall be so constituted as to give, as nearly as is practicable, representation in proportion to the population of the district."[16] The Redistricting Coalition of Virginia proposes either an independent commission or a bipartisan commission that is not polarized. Member organizations include the League of Women Voters of Virginia, AARP of Virginia, OneVirginia2021, the Virginia Chamber of Commerce and Virginia Organizing.[17] Governor Bob McDonnell's Independent Bipartisan Advisory Commission on Redistricting for the Commonwealth of Virginia made its report on April 1, 2011. It made two recommendations for each state legislative house that showed maps of districts more compact and contiguous than those adopted by the General Assembly.[18] However, no action was taken after the report was released.

In 2011 the Virginia College and University Redistricting Competition was organized by Professors Michael McDonald of George Mason University and Quentin Kidd of Christopher Newport University. About 150 students on sixteen teams from thirteen schools submitted plans for legislative and U.S. Congressional Districts. They created districts more compact than the General Assembly's efforts. The "Division 1" maps conformed with the Governor's executive order, and did not address electoral competition or representational fairness. In addition to the criteria of contiguity, equipopulation, the federal Voting Rights Act and communities of interest in the existing city and county boundaries, "Division 2" maps in the competition did incorporate considerations of electoral competition and representational fairness. Judges for the cash award prizes were Thomas Mann of the Brookings Institution and Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute.[19]

In January 2015 Republican state senator Jill Holtzman Vogel of Winchester and Democratic state senator Louise Lucas of Portsmouth sponsored a Senate Joint Resolution to establish additional criteria for the Virginia Redistricting Commission of four identified members of political parties, and three other independent public officials. The criteria began with respecting existing political boundaries, such as cities and towns, counties and magisterial districts, election districts and voting precincts. Districts are to be established on the basis of population, in conformance with federal and state laws and court cases, including those addressing racial fairness. The territory is to be contiguous and compact, without oddly shaped boundaries. The commission is prohibited from using political data or election results to favor either political party or incumbent. It passed with a two-thirds majority of 27 to 12 in the Senate, and was then referred to committee in the House of Delegates.[20]

In 2015, in Vesilind v. Virginia State Board of Elections in a Virginia state court, plaintiffs sought to overturn the General Assembly's redistricting in five House of Delegates and six state Senate districts as violations of both the Virginia and U.S. Constitutions because they failed to represent populations in "continuous and compact territory".[21]

In 2020, a constitutional amendment moved redistricting power to a commission consisting of eight lawmakers, four from each party, and eight citizens.[22] The amendment passed with all counties and cities supporting the measure except Arlington.[23] The commission failed to reach an agreement on new state and congressional districts by an October 25, 2021, deadline, and relied upon the amendment's provision that lets the state Supreme Court of Virginia draw the districts in the event that the commission could not do so.[24] The Supreme Court did so and approved newly drawn districts on December 28, 2021.[25] While newly drawn districts will currently first be used in 2023, a federal lawsuit is pending that calls for an election to be held using newly drawn districts as immediately as November 2022. If the lawsuit was successful, it would have required all House districts, which just held elections under the previous districts in 2021, to hold back-to-back elections in 2022 and 2023 under the newly drawn districts.[26]

See also

[edit]- Senate of Virginia

- Virginia House of Delegates

- Virginia State Capitol

- List of Virginia state legislatures

References

[edit]- ^ "The First General Assembly | Historic Jamestowne". Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ "House History". history.house.virginia.gov. Archived from the original on June 22, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ "Newly-Empowered Virginia Democrats Promise Action". Voice of America. Associated Press. January 8, 2020. Archived from the original on January 11, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ "Asombra diversidad étnica de nueva Legislatura de Virginia" (in Spanish). Chron. January 8, 2020. Archived from the original on January 8, 2020.

- ^ "General Assembly Building Webcams". virginiageneralassembly.gov. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ "About the General Assembly". Virginia's Legislature. State of Virginia. Archived from the original on May 27, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- ^ Billings; Warren, M. (2004). A Little Parliament; The Virginia General Assembly in the Seventeenth Century. Richmond: The Library of Virginia, in partnership with Jamestown 2007/Jamestown Yorktown Foundation.

- ^ Barradall, Edward, and Randolph, John. Virginia Colonial Decisions. United States, Boston book Company, 1909. v. 1, p. 63.

- ^ Virginia (1905). Annual Reports of Officers, Boards and Institutions of the Commonwealth of Virginia, Report of the State Librarian, Volume II. p. 543.

- ^ General Information: Senate Archived 2012-06-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ General Information: House of Delegates Archived May 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Virginia Budget". Legislative Information Service. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ Constitution of Virginia Archived June 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Art. IV, § 4 Archived June 29, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Art. IV, Sect. 6 Constitution of Va.

- ^ "Article IV. Legislature - Section 6. Legislative sessions". Constitution of Virginia. Virginia Law. Archived from the original on November 12, 2023.

- ^ "Article II, Section 6. Apportionment". Virginia Constitution. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved October 10, 2006 – via Justia.

- ^ "Coalition Members". Virginia Redistricting Coalition. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014.

- ^ The Public Interest in Redistricting[permanent dead link] Bob Holsworth, Chair for the Independent Bipartisan Advisory Commission on Redistricting, Commonwealth of Virginia, April 1, 2011, pp. 22–27.[dead link]

- ^ The Public Interest in Redistricting[permanent dead link] Bob Holsworth, Chair for the Independent Bipartisan Advisory Commission on Redistricting, Commonwealth of Virginia, April 1, 2011, pp. 9–10.[dead link]

- ^ "Senate Joint Resolution No. 284 Archived December 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Amendment in the Nature of a Substitute (Proposed by the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections on January 20, 2015) (Patrons Prior to Substitute – Senators Vogel and Lucas [SJR 224])".

- ^ "Vesilind v. Virginia State Board of Elections" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Virginia Redistricting Commission Amendment (2020)". Ballotpedia. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ "2020 November General". Virginia Elections. Virginia Department of Elections. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Redistricting Commission to Miss Last Deadline; Supreme Court to Choose Special Masters". WVTF. November 8, 2021. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ "Redistricting process changes impact new maps". www.cbs19news.com. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ "Civil rights group asks to join Virginia redistricting suit". AP NEWS. March 21, 2022. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2022.