Wellington tramway system

| Wellington tramway system | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A former Wellington tram (Double Saloon No. 159, built 1925) at the Wellington Tramway Museum. | |||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||

| Locale | Wellington, New Zealand | ||||||||||||

| Open | 1878 | ||||||||||||

| Close | 1964 | ||||||||||||

| Status | Closed | ||||||||||||

| Owner(s) | Wellington City Council (from 1 August 1900) | ||||||||||||

| Infrastructure | |||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft (1,219 mm) | ||||||||||||

| Propulsion system(s) | Steam (1878-1882), Horse-drawn (1882-1904), Electric (from 1904) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The Wellington tramway system (1878–1964) operated in Wellington, the capital of New Zealand.[1] The tramways were originally owned by a private company, but were purchased by the city and formed a major part of the city's transport system. Historically, it was an extensive network, with steam and horse trams from 1878 and then electric trams ran from 1904 to 1964, when the last line from Thorndon to Newtown was replaced by buses.

Background

[edit]In 1872, Tramways Act was passed and allowed for the construction of tramways and both local authorities and private companies were able to run them.[2][3] The flowing year, Charles O'Neill proposed a plan to lay down tracks and operate a tramway submitted to the Wellington City Council.[4]

A deed was awarded to O'Neill on 23 March 1876, granted by the City Council.[5] The deed granted the power to construct a tramway, with O'Neill and his team committing to start works within six months and finish within 18 months. The agreement was for ten years, with the City Council having the right to extend the line at any time.[5] The City Council had the right to purchase the tramway after 10 years or to remove the tracks.[5]

On 29 June 1876, William Fitzherbert signed the order authorising the construction of the tramways which confirmed the terms of the City Council's deed.[6] On 9 January 1877, locomotives, carriages, and rails had been ordered from England; and work begin to lay down tracks.[7]

Initially, in 1878, Wellington's trams were steam-powered, with an engine drawing a separate carriage.[8] The engines were widely deemed unsatisfactory, however — they created a great deal of soot, were heavy (increasing track maintenance costs), and often frightened horses.[9][10] By 1882, a combination of public pressure and financial concerns caused the engines to be replaced by horses.[11][12] In 1902, after the tramways came into public ownership, it was decided to electrify the system, and the first electric tram ran in 1904.[13] Trams operated singly, and were mostly single-deck with some (open-top) double-deck.[14]

History

[edit]Early tramways: 1878-1900

[edit]

The first tram line in Wellington opened on 24 August 1878 at a cost of £40,000.[15][16] The line was 4.5 km in length and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge; and ran between the north end of Lambton Quay and a point just south of the Basin Reserve with the Governor George Phipps riding the first tram at 10 km/h.[17] During its early operation, the tramway boasted four steam trams, each connected to passenger trailers for seating.[18][19] The tramway company also had two horse-drawn cars for horses to use to pull some of the passengers.[18][20]

The steam trams caused complaints over noise, being a nuisance, soot, frightened horses, and collisions, which led to civil court cases.[21][17][22] They proved unpopular with cabmen, carters, and some residents, who organised a meeting.[18] It was decided to petitioned for their removal.[23] On 4 December 1879 a petition was handed over to Governor Hercules Robinson requesting the use of animal power only for Wellington’s trams.[24] The Wellington City Tramways Company went into voluntary liquidation in 1879 and was sold to private owners.[25] A Shareholder meeting was held on 8 January 1880 to formally agreed the company to be wound up voluntarily.[26]

In March 1880, an auction was held, and the new owner was the sole bidder, Edward William Mills, who bid £19,250 and became the director.[27] In January 1882, the introduction of horse-drawn trams led to the removal of steam trams from service. Stalls for horses replaced the engine shed on Adelaide Road, which was made to hold 50 horses and was gradually enlarged to 140 horses.[28][29] The horses were brought over from the Wairarapa to pull the trams and chaff was obtained from Sanson.[29] The Tramway Company's deed with the City Council was due to expire in July 1887. A council-appointed committee recommended buying the tramway. However, the Council didn't proceed at this stage.[30]

In May 1900 the City Council held a meeting on purchasing the Wellington City Tramways and their rolling stock, horses, tools, and the rails.[31] In June 1900, City Council gave public notice of its intent to purchase the Wellington City Tramways.[32] On 1 October 1900, the City Council became the owner, paying £19,382. The Wellington Corporation Tramways Department was established to manage the tram service.[33] The Wellington City Council purchased the tram company and took over from 1 August 1900, although it was not until 1902 that the street lease expired.[34][35]

Electric era: 1901–1964

[edit]Electrification

[edit]In 1901, the City Council made enquiries into the electrification of the tramway, and it was decided to move forward with electrification.[28] In 1902 the City Council borrowed £225,000 through the Tramways Department and invested the funds in the extension and electrification of the tramway network.[36] The system was electrified with a contract let in 1902 and converted to the then-new 4 ft (1,219 mm) gauge.[37] The trams used electric power to move along rails, requiring extensive infrastructure like new rails, overhead wires, and tram poles.[38] Tram poles were placed at half-mile intervals on the side of the streets, made of steel sections with a slightly tapered diameter. Topped with a ball and spike finial for ornamental and water protection, bracket arms carried a double insulation system for overhead wires to power them to 500-550 volts.[39] The tram utilised various devices to collect power from overhead lines, with a roof-mounted trolley pole being the most common—the trolley pole connected to the overhead line was maintained by pressure from the spring-loaded trolley base.[40] The first trial electric tram run was on 8 June 1904, and the first run from Newtown to the Basin Reserve was on 30 June 1904.[41][42]

Expansion

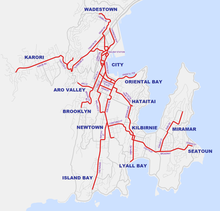

[edit]Extensions in 1904 were to Courtenay Place, Cuba and Wallace Street, Aro Street, Oriental Bay, and Tinakori Road.[43] The following year, a line was constructed through Newtown and Berhampore to Island Bay, and the year after, from the Te Aro line to Brooklyn. In 16 April 1907, a dedicated single track tram tunnel to Hataitai was completed, allowing services to reach Kilbirnie, Miramar, and Seatoun which cost £70,000.[44][45] In 1907, the Tinakori Road line was extended westward towards Karori, reaching Karori Cemetery.[46] In February 1911, the line to Karori was extended up Church Hill to Karori Park.[47] The City boundary was at the Wellington Botanic Garden in Tinakori Road and the Karori Borough Council was responsible past the Gardens. As with the Melrose Borough Council in 1903, the one council's operation of the city tramways was a factor in the amalgamation of Karori Borough Council with the Wellington City Council in 1920[48] Construction of the new track then slowed but did not stop. In 1909, a line was built from Kilbirnie to Lyall Bay and then another from Tinakori Road to Wadestown.[49] In 1915, a line was built to connect Newtown with Kilbirnie, via Constable Street and Crawford Road.[50] In 1911, two tramcars were built for freight and parcels service between the city and the suburbs and deports were established througth out the city.[51]

In 1924, a case went to the Court of Appeal of New Zealand challenging the use of eminent domain to secure right-of-ways for tracks. In Boyd v Mayor of Wellington, the court found that, although the government forced the sale of land improperly, it had acted in good faith so the sale was not reversed.[52]

In 4 June 1929, the last new line was completed, a branch of the Karori line through a tunnel to Northland.[53] Finally, in 1940, a shorter route was opened up Bowen Street to the western suburbs of Karori and Northland instead of the route via Tinakori Road. This had been proposed since 1907, but successive prime ministers (Ward and Massey) opposed noisy trams using Bowen Street or Hill Street close to parliament. A 1935 demonstration by a Fiducia tram convinced the speaker and members of the Legislative Council that modern trams were silent.[54]

Wellington's more northern suburbs, such as Johnsonville and Tawa, were not served by the tram network, as they were (and are) served by the Wellington railway system.[55] [56]The Wellington Cable Car, another part of Wellington's transport network, is sometimes described as a tram but is not generally considered so, being a funicular railway. It was opened in 1902 and is still in operation.[57] Wellington's electric tramways had the unusual gauge of 4 ft (1,219 mm), a narrow gauge. The steam and horse trams were 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge, also narrow and the same as New Zealand's national railway gauge.[58][59]

Demise

[edit]Abandonment

[edit]In 1925, the tram freight and parcel services were discontinued because of competition from motor vehicles.[51] In the late 1940s and early 1950s, it was decided to replace the trams with buses and trolleybuses, which were seen as more advanced and better suited to the city's needs.[8] The topography of Wellington and the reductions in passengers and the high cost of trams played a part in this decision.[60][61] The city's streets are often steep, winding, and narrow, making the greater manoeuvrability of buses a significant asset. On 9 September 1953, the City Council announced that the Northland trams would be converted to buses from 21 September. However, a week later the announced decision was rescinded because the City Council had not obtained the necessary Order in Council from the Ministry of Works. It delayed the conversion, but by 17 September 1954 it made the Northland trams the shortest-lived service for the city.[62] Saul Goldsmith started a campaign called "Save the trams" in 1959.[63] Campaigners for the movement made a proposed to retain the line from the railway station to Courtenay Place.[64] On 22 June 1960, a poll passed and approved the City Council's proposal to borrow £1,282,230 to convert the trams to buses.[65] In the 1962 Wellington City mayoral election Goldsmith stood for the retention of what's left of the Wellington tramway system.[66] The principle of electric transport was retained – many of the tram routes were served by trolleybuses until 2017.[67]

Closure

[edit]The first major line closure came in 1949 when Wadestown closed.[68] The following year the Oriental Bay line closed. In 1954, the Karori line (including the Northland branch) closed. In 1957 services to Aro Street and Brooklyn ended, and the construction of Wellington International Airport destroyed the route to Miramar and Seatoun. All services to the eastern suburbs had ceased by 1962, with Lyall Bay closing in 1960,[69] Constable St/Crawford Rd in 1961, and Hataitai in 1962.[nb 1] In 1963, the service to Island Bay was withdrawn, leaving mainly inner-city routes. On 2 May 1964, the remaining portion was closed, with a parade from Thorndon to Newtown.[70] Some of Wellington's old trams have been preserved, and are now in operation at the Wellington Tramway Museum at Paekākāriki.

Proposed systems

[edit]Occasionally, it has been suggested that trams should return to Wellington, either in a modern form or as a historical display. As early as 1979, converting the Johnsonville Railway line to a tram operation was suggested. In 1992, the 'Superlink' plan proposed converting the Johnsonville line to light rail and extending the system to the Airport and Karori via a tunnel from Holloway Road in Aro Valley to Appleton Park, it won the endorsement of many locals and some politicians and prompted further investigation into light rail as a mode of transport for Wellington. In the 1990s, a heritage line was proposed for the city's waterfront. More recently, in 2022, a proposal for a light rail line running from the Wellington city centre to Courtenay Place, then past the Wellington Hospital to the south coast at Island Bay, was part of Let's Get Wellington Moving. In mid-December 2023, the Minister of Transport, Simeon Brown, ordered the New Zealand Transport Agency to cease funding. [71]

List of dates

[edit]The years of opening and closing of various tram routes are:[72]

| Route | Opened | Closed | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aro Street | 1904 | 1957 | |

| Brooklyn | 1906 | 1957 | |

| Hataitai | 1907 | 1962 | |

| Hataitai/Kilbirnie/Miramar | 1907 | 1957 | via Hataitai tram tunnel |

| Island Bay | 1905 | 1963 | |

| Karori | 1907 | 1954 | |

| Kilbirnie | 1915 | 1961 | via Crawford Road |

| Lyall Bay | 1911 | 1960 | |

| Newtown/Thorndon | 1904 | 1964 | |

| Northland | 1929 | 1954 | branch of Karori route |

| Oriental Bay | 1904 | 1950 | |

| Seatoun | 1907 | 1958 | |

| Tinakori Road | 1904 | 1949 | extended to Karori |

| Wadestown | 1911 | 1949 |

Remnants

[edit]Some of Wellington's old trams have been preserved, and are now in operation at the Wellington Tramway Museum at Queen Elizabeth Park in Paekākāriki on the Kāpiti Coast and at the Museum of Transport and Technology in Auckland.[73] In 2024, the city council laid historic tram tracks on the Parade in Island Bay as a part of a village upgrade to represent when trams ran along The Parade.[74][75] The Wellington Tramway Museum had agreed to provide two ten-meter-long rails for the street display on The Parade. The museum prepared the rails, trimming them to the required length, drilling holes, fitting tie bars, cleaning rust, and painting the rail tops. An interpretation panel was set up to explain the history of trams in the suburb.[76]

See also

[edit]- Trams in New Zealand

- Christchurch tramway system

- Light rail in Auckland

- Public transport in the Wellington Region

- Public transport in New Zealand

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ The Hataitai tram tunnel is still used by buses.

Citations

- ^ "Trams in Wellington, 1878-1964". Wellington City Libraries. Wellington City Council. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ "Tramways Act 1872 (36 Victoriae 1872 No 22)". NZLII. 25 October 1872. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "THE TRAMWAYS ACT, Issue 1096". Otago Witness. 30 November 1872. p. 1. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "STREET TRAMWAY, Volume XXVIII, Issue XXVIII". Wellington Independent. 18 February 1873. p. 2. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ a b c "THE WELLINGTON CITY STEAM TRAMWAYS, Issue 5264". Otago Daily Times. 1 January 1879. p. 1. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "WELLINGTON, Volume XIX, Issue 3101". Wanganui Chronicle. 30 June 1876. p. 2. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "LATEST TELEGRAMS, Issue 2739". Star (Christchurch). 9 January 1877. p. 2. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ a b "Ngā Kā Rēra i Te Whanganui-a-Tara, 1878-1964 Trams in Wellington, 1878-1964". Wellington City Libraries. 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Kelly 1996, p. 58.

- ^ "Volume XXXIII, Issue 5432". New Zealand Times. 24 August 1878. p. 2. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "LOCAL & GENERAL, Volume XVI, Issue 1217". Wairarapa Standard. 28 January 1882. p. 2. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "THE WELLINGTON TRAMWAY COMPANY, Volume XLI, Issue 7009". New Zealand Times. 8 November 1883. p. 2. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "New Zealand's last electric tram trip". New Zealand History. 5 November 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Electric tram in Island Bay". Wellington City Recollect. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "FIFTY, NOT OUT!, Volume CVI, Issue 40". Evening Post. 25 August 1928. p. 17. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Wellington steam-tram service opened". New Zealand History. 27 July 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ a b Stewart 1973, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Lawes 1964, p. 4.

- ^ Humphris, Adrian (11 March 2010). "Public transport - Horse and steam trams". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "Lambton Quay". Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "WELLINGTON STEAM TRAMWAYS, Volume XVI, Issue 289". Evening Post. 6 December 1878. p. 2. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "RESIDENT MAGISTRATE'S COURT. THIS DAY, Volume XVI, Issue 273". Evening Post. 18 November 1878. p. 2. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ New Zealand, Archives. "1879 Petition against Steam Trams". flickr. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 14.

- ^ "THE TRAMWAYS COMPANY, Volume XVIII, Issue 150". Evening Post. 23 December 1879. p. 2. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "Page 3 Advertisements Column 1". Evening Post. 17 February 1880. p. 3. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "SALE OF THE TRAMWAY PLANT, Volume XIX, Issue 68". Evening Post. 24 March 1880. p. 2. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ a b Lawes 1964, p. 5.

- ^ a b Stewart 1973, p. 33.

- ^ "WELLINGTON TRAMWAYS, Issue 153". Auckland Star. 1 July 1887. p. 5. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "MUNICIPALISATION OF OUR TRAMWAYS, Volume LIX, Issue 128". Evening Post. 31 May 1900. p. 6. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Page 8 Advertisements Column 7, Volume LIX, Issue 129". Evening Post. 1 June 1900. p. 8. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "THE CITY TRAMWAYS. THE CORPORATION TAKES POSSESSION, Volume LX, Issue 79". Evening Post. 1 October 1900. p. 6. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Timeline - We Built This City". Archives Online. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "SOME CITY PROJECTS, Volume LXXI, Issue 4040". New Zealand Times. 3 May 1900. p. 4. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "LOAN CONSOLIDATION, Volume LXXII, Issue 4583". New Zealand Times. 11 February 1902. p. 5. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ Parliament 1902, p. 4.

- ^ "Re NZ Electrical Syndicate poles, Tramways Engineer". Wellington City Council Archives. 7 May 1903. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ Irvine, Kerrigan & Cawte 2023, p. 4.

- ^ Irvine, Kerrigan & Cawte 2023, p. 12.

- ^ Duncan, James; McAlpine, Christen (2021). "Tram No. 135 and its century of travelling the tracks". New Zealand: The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT). Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Parsons 2010, p. 177.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 35,201.

- ^ Lawes 1964, p. 12.

- ^ Humphris, Adrian (11 March 2010). "Wellington tram tunnel". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "THEN. AND NOW, Volume 1, Issue 7". Dominion. 3 October 1907. p. 4. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Taylor, James (6 June 2006). "Glendaruel 316 Karori Road, Karori, WELLINGTON". New Zealand Historic Places Trust. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Patrick 1990, p. 40, 41, 50.

- ^ "BY TRAM TO LYALL BAY, Volume LXXVIII, Issue 145". Evening Post. 16 December 1909. p. 7. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Efford, Brent (26 August 2017). "Welcome and sensible: the Greens' plan for light rail". Wellington.Scoop. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ a b Lawes 1964, p. 18.

- ^ Scott, Struan (1999). "INDEFEASIBILITY OF TITLE AND THE REGISTRAR'S 'UNWELCOME' S81 POWERS". NZLII. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ "The Opening of a "Famous" Tunnel in New Zealand". Transportation History. 4 June 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 168.

- ^ "Kapiti Line (Waikanae – Wellington) – Metlink". www.metlink.org.nz. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ "Johnsonville Line (Wellington-Johnsonville) Metlink". www.metlink.org.nz. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ "Cable Car HISTORY". Wellington Cable Car. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Cook, Stephen. "WELLINGTON TRAMWAY SYSTEM MAP". Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "New Zealand's rail network". LEARNZ. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "General News". Press. 6 April 1961. p. 14. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ "TRANSPORT LOSS IN WELLINGTON, Volume C, Issue 29591". Press. 14 August 1961. p. 13. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ Lawes 1964, p. 14.

- ^ "Last Trip For N.Z.'s Last Tram, Volume CIII, Issue 3043". Press. 4 May 1964. p. 3. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 214.

- ^ "General News". Press. 23 June 1960. p. 14. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ Traue, James Edward, ed. (1978). Who's Who in New Zealand, 1978 (11th ed.). Wellington: Reed Publishing. p. 124.

- ^ Budach, Dirk (31 October 2019). "New Zealand: 56 modern trolleybuses out of service for 2 years now". Urban Transport Magazine. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ "Highland Park Tram Shelter (Former), Wadestown". Wellington Heritage. 7 June 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ "CHANGEOVER TO BUSES". Press. 1 August 1960. p. 10. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 2.

- ^ Coughlan, Thomas. "Government and councils agree to kill $7.4b Wellington transport plan". The New Zealand Herald.

- ^ Parsons 2010, p. 193.

- ^ "Tram [No. 47 (Double Decker)]". MOTAT. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ "Island Bay Parade Safety Improvement and Upgrade" (PDF). Wellington City Council. 30 July 2024. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ "Island Bay village upgrades". Wellington City Council. November 2024. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ Carter 2024, p. 171.

Bibliography

Not by author; sorted by publication name

- Patrick, Margaret G (1990). From bush to suburb : Karori, 1840-1980. Wellington: Karori Historical Society. p. 72. ISBN 0-473-00915-3.

- Irvine, Susan; Kerrigan, Carole-Lynne; Cawte, Hayden (2023). Historic Heritage Evaluation (PDF). Wellington: Wellington City Council. p. 45.

- Kelly, Michael (1996). Old Shoreline Heritage Trail (PDF). Wellington: Wellington City Council. p. 69.

- Stewart, Graham (1973). The End of the Penny Section: A History of Urban Transport in New Zealand. Wellington: Reed. p. 260. ISBN 0-589-00720-3.

- Carter, Graeme (2024). The New Zealand Railway Observer October - November 2024 Volume 81, N०4. Wellington: The New Zealand Railway & Locomotive Society. p. 41. ISSN 0028-8624.

- Parliament, New Zealand (1902). Wellington City Electric Tramway : Order in Council. Wellington: NZ Parliament. p. 10.

- Parsons, David (2010). Wellington's Railway: Colonial Steam to Matangi. Wellington: Wellington: Wellington City Council. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-908573-88-2.

- Lawes, John William (1964). Wellington Tramway Memories. Wanganui: R. B. Alexander. p. 35.

External links

[edit]- Wellington Tramway Museum

- Vehicular Traffic (Carriages, Tramways etc) in Cyclopaedia of New Zealand Volume I (Wellington) of 1897

- Wellington Electric Tram 1904 on 1985 45c stanp

- View Photos (405) via Archives Search: search for 'tram', tick images only

- Photo of horse tram on The Quay 1900

- Photo of woman tram conductor 1943

- Photo of woman tramway employees repairing track 1944

- Article about opening of Lyall Bay line

- "Photo of double saloon tram in front of Old Government Building". NZRLS. 2022.

- "Trams and Trolley buses at Wellington Railway Station (1963 photo)". National Library. 2022.

- "Horse Trams Cuba street, corner of Dixon St: 1885 (photo)". WCC Archives. 2024.