Western Christianity

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

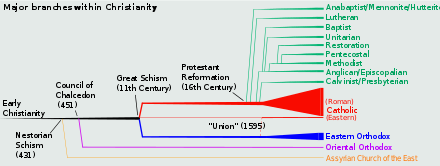

Western Christianity is one of two subdivisions of Christianity (Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the Old Catholic Church, Independent Catholicism and Restorationism.

The large majority of the world's 2.3 billion Christians are Western Christians (about 2 billion: 1.2 billion Latin Catholic and 1.17 billion Protestant).[3][4] One major component, the Latin Church, developed under the bishop of Rome. Out of the Latin Church emerged a wide variety of independent Protestant denominations, including Lutheranism and Anglicanism, starting from the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, as did Independent Catholicism in the 19th century. Thus, the term "Western Christianity" does not describe a single communion or religious denomination but is applied to distinguish all these denominations collectively from Eastern Christianity.

The establishment of the distinct Latin Church, a particular church sui iuris of the Catholic Church, coincided with the consolidation of the Holy See in Rome, which claimed primacy since Antiquity. The Latin Church is distinct from the Eastern Catholic Churches, also in full communion with the Pope in Rome, and from the Eastern Orthodox Church and Oriental Orthodox Churches, which are not in communion with Rome. These other churches are part of Eastern Christianity. The terms "Western" and "Eastern" in this regard originated with geographical divisions mirroring the cultural divide between the Hellenistic East and Latin West and the political divide between the Western and Eastern Roman empires. During the Middle Ages, adherents of the Latin Church, irrespective of ethnicity, commonly referred to themselves as "Latins" to distinguish themselves from Eastern Christians ("Greeks").[5]

Western Christianity has played a prominent role in the shaping of Western civilization.[6][7][8][9] With the expansion of European colonialism from the Early Modern era, the Latin Church, in time along with its Protestant secessions, spread throughout the Americas, much of the Philippines, Southern Africa, pockets of West Africa, and throughout Australia and New Zealand. Thus, when used for historical periods after the 16th century, the term "Western Christianity" does not refer to a particular geographical area but is used as a collective term for all these.

Today, the geographical distinction between Western and Eastern Christianity is not nearly as absolute as in Antiquity or the Middle Ages, due to the spread of Christian missionaries, migrations, and globalisation. As such, the adjectives "Western Christianity" and "Eastern Christianity" are typically used to refer to historical origins and differences in theology and liturgy rather than present geographical locations.[citation needed]

While the Latin Church maintains the use of the Latin liturgical rites, Protestant denominations and Independent Catholicism use various liturgical practices.

The earliest concept of Europe as a cultural sphere (instead of simply a geographic term) appeared during the Carolingian Renaissance of the 9th century, which included territories that practiced Western Christianity at the time.[10]

History

[edit]

For much of its history, the Christian church has been culturally divided between the Latin-speaking West, whose centre was Rome, and the Greek-speaking East, whose centre was Constantinople. Cultural differences and political rivalry created tensions between the two churches, leading to disagreement over doctrine and ecclesiology and ultimately to schism.[11]

Like Eastern Christianity, Western Christianity traces its roots directly to the apostles and other early preachers of the religion. In Western Christianity's original area, Latin was the principal language. Christian writers in Latin had more influence there than those who wrote in Greek, Syriac, or other languages. Although the first Christians in the West used Greek (such as Clement of Rome), by the fourth century Latin had superseded it even in the cosmopolitan city of Rome, as well as in southern Gaul and the Roman province of Africa.[12] There is evidence of a Latin translation of the Bible as early as the 2nd century (see also Vetus Latina).

With the decline of the Roman Empire, distinctions appeared also in organization, since the bishops in the West were not dependent on the Emperor in Constantinople and did not come under the influence of the Caesaropapism in the Eastern Church. While the see of Constantinople became dominant throughout the Emperor's lands, the West looked exclusively to the see of Rome, which in the East was seen as that of one of the five patriarchs of the Pentarchy, "the proposed government of universal Christendom by five patriarchal sees under the auspices of a single universal empire. Formulated in the legislation of the emperor Justinian I (527–565), especially in his Novella 131, the theory received formal ecclesiastical sanction at the Council in Trullo (692), which ranked the five sees as Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem."[13]

Over the centuries, disagreements separated Western Christianity from the various forms of Eastern Christianity: first from East Syriac Christianity after the Council of Ephesus (431), then from that of Oriental Orthodoxy after the Council of Chalcedon (451), and then from Eastern Orthodoxy with the East-West Schism of 1054. With the last-named form of Eastern Christianity, reunion agreements were signed at the Second Council of Lyon (1274) and the Council of Florence (1439), but these proved ineffective.

Historian Paul Legutko of Stanford University said the Catholic Church is "at the center of the development of the values, ideas, science, laws, and institutions which constitute what we call Western civilization".[14] The rise of Protestantism led to major divisions within Western Christianity, which still persist, and wars—for example, the Anglo-Spanish War of 1585–1604 had religious as well as economic causes.

In and after the Age of Discovery, Europeans spread Western Christianity to the New World and elsewhere. Roman Catholicism came to the Americas (especially South America), Africa, Asia, Australia and the Pacific. Protestantism, including Anglicanism, came to North America, Australia-Pacific and some African locales.

Today, the geographical distinction between Western and Eastern Christianity is much less absolute, due to the great migrations of Europeans across the globe, as well as the work of missionaries worldwide over the past five centuries.

| Part of a series on |

| Christian culture |

|---|

|

| Christianity portal |

Features

[edit]

Original sin

[edit]Original sin, also called ancestral sin,[15][16][17][18] is a Christian belief in a state of sin in which humanity has existed since the fall of man, stemming from Adam and Eve's rebellion in the Garden of Eden, namely the sin of disobedience in consuming the forbidden fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.[19] Theologians have characterized this condition in many ways, seeing it as ranging from something as insignificant as a slight deficiency, or a tendency toward sin yet without collective guilt, referred to as a "sin nature", to something as drastic as total depravity or automatic guilt of all humans through collective guilt.[20]

Filioque clause

[edit]Most Western Christians use a version of the Nicene Creed that states that the Holy Spirit "proceeds from the Father and the Son", where the original text as adopted by the First Council of Constantinople had "proceeds from the Father" without the addition of either "and the Son" or "alone". This Western version also has the additional phrase "God from God" (Latin: Deum de Deo), which was in the Creed as adopted by the First Council of Nicaea, but which was dropped by the First Council of Constantinople.

Date of Easter

[edit]The date of Easter usually differs between Eastern and Western Christianity, because the calculations are based on the Julian calendar and Gregorian calendar respectively. However, before the Council of Nicea, various dates including Jewish Passover were observed. Nicea "Romanized" the date for Easter and anathematized a "Judaized" (i.e. Passover date for) Easter. The date of observance of Easter has only differed in modern times since the promulgation of the Gregorian calendar in 1582; and further, the Western Church did not universally adopt the Gregorian calendar at once, so that for some time the dates of Easter differed between the Eastern Church and the Roman Catholic Church, but not necessarily as between the Eastern Church and the Western Protestant churches. For example, the Church of England continued to observe Easter on the same date as the Eastern Church until 1753.

Even the dates of other Christian holidays often differ between Eastern and Western Christianity.

Lack of essence–energies distinction

[edit]Eastern Christianity, and particularly the Eastern Orthodox Church, has traditionally held a distinction between God's essence, or that which He is, with God's energies, or that which He does. They hold that while God is unknowable in His essence, He can be known (i.e. experienced) in His energies. This is an extension of Eastern Christianity's apophatic theology, while Western Christians tend to prefer a view of divine simplicity, and claim that God's essence can be known by its attributes.

Western denominations

[edit]Today, Western Christianity makes up close to 90% of Christians worldwide with the Catholic Church accounting for over half and various Protestant denominations making up another 40%.

Hussite movements of 15th century Bohemia preceded the main Protestant uprising by 100 years and evolved into several small Protestant churches, such as the Moravian Church. Waldensians survived also, but blended into the Reformed tradition.

Major figures

[edit]Bishop of Rome or the pope

[edit]Relevant figures:

- Clement of Rome (fl. c. 96), one of the apostolic fathers of the church.

- Pope Leo I

- Gregory the Great

The Reformers

[edit]Relevant figures:

- Jan Hus (c. 1369–1415), one of the most relevant theologians in the 14th century.

- Martin Luther (1483–1546), the most famous reformer and theologian in the Reformation and in the 15th century.

- Hans Tausen, Bishop of Ribe (1494–1561), leading theologian of the Reformation in Denmark and Holstein.

- Laurentius Petri, Archbishop of Uppsala and all Sweden (1499–1573), along with his brother Olaus Petri were regarded as the main Lutheran reformers of Sweden, together with the king Gustav I of Sweden.

- Primož Trubar (1508–1586), mostly known as the author of the first Slovene language printed book,[21] the founder and the first superintendent of the Protestant Church of the Duchy of Carniola, and for consolidating the Slovenian language.

- John Calvin (1509–1564)

- John Knox (1514–1572)

- Ferenc Dávid (1520–1579) founder of the Unitarian Church of Transylvania who laid the foundation for what would become the nontrinitarian movement.

- Mikael Agricola, bishop of Turku (1554–1557), he became the de facto founder of literary Finnish and a prominent proponent of the Protestant Reformation in Sweden, including Finland, which was a Swedish territory at the time. He is often called the "father of literary Finnish".

Archbishop of Canterbury and primate of all England

[edit]Relevant figures:

- Augustine of Canterbury (597–604)

- Thomas Cranmer (1533–1555), one of the major reformers in England

- Matthew Parker (1504–1575),(Parker was one of the primary architects of the Thirty-nine Articles)

Archbishop of Lyon and primate of the Gauls

[edit]Relevant figures:

- Irenaeus of Lyon (died c. 202)

Patriarch of Aquileia

[edit]Relevant figures:

See also

[edit]- Aristotelianism

- Augustinianism

- Bohemian Reformation

- Calvinism

- Latin Church Fathers

- Ecclesiastical differences between the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church

- Holy Roman Empire

- List of Christian denominations

- Neoplatonism

- Radical Reformation

- Scholasticism

- Swiss Reformation

- Theological differences between the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church

- Thomism

- Western culture

- Western religions

References

[edit]- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Agnus Dei (In Liturgy)". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Vatican City". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ "Status of Global Christianity, 2024, in the Context of 1900–2050" (PDF). Center for the Study of Global Christianity, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

Protestants: 625,606,000; Independents: 421,689,000; Unaffiliated Christians: 123,508,000

- ^ Center, Pew Research (19 December 2011). "Global Christianity - A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "Distinguishing the terms: Latins and Romans". Orbis Latinus.

- ^ Perry, Marvin; Chase, Myrna; Jacob, James; Jacob, Margaret; Von Laue, Theodore H. (1 January 2012). Western Civilization: Since 1400. Cengage Learning. p. XXIX. ISBN 978-1-111-83169-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Roman Catholicism". Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 August 2023.

Roman Catholicism, Christian church that has been the decisive spiritual force in the history of Western civilization.

- ^ Hayas, Caltron J.H. (1953). Christianity and Western Civilization. Stanford University Press. p. 2.

That certain distinctive features of our Western civilization—the civilization of western Europe and America—have been shaped chiefly by Judaeo – Graeco – Christianity, Catholic, and Protestant.

- ^ Orlandis, José (1993). A Short History of the Catholic Church. Four Courts Press.

- ^ Dr. Sanjay Kumar (2021). A Handbook of Political Geography. K.K. Publications. p. 127.

- ^ "General Essay on Western Christianity", Overview Of World Religions. Division of Religion and Philosophy, University of Cumbria. © 1998/9 ELMAR Project. Accessed 1 April 2012.

- ^ "Latin". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. 2005. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- ^ "Pentarchy | Byzantine Empire, Justinian I & Justinian Code | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ Woods, Jr., Thomas. "Review of How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization". National Review Book Service. Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ^ Golitzin, Alexander (1995). On the Mystical Life: The Ethical Discourses. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-0-88141-144-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ Tate, Adam L. (2005). Conservatism and Southern Intellectuals, 1789–1861: Liberty, Tradition, and the Good Society. University of Missouri Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8262-1567-3.

- ^ Bartolo-Abela, Marcelle (2011). God's Gift to Humanity: The Relationship Between Phinehas and Consecration to God the Father. Apostolate-The Divine Heart. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-0-9833480-1-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hassan, Ann (2012). Annotations to Geoffrey Hill's Speech! Speech!. punctum. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-1-4681-2984-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ Cross 1966, p. 994.

- ^ Brodd, Jeffrey (2003). World Religions. Winona, MN: Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

- ^ "Trubar Primož". Slovenian Biographical Lexicon. Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2013.