William Hulme (British Army officer)

William Hulme | |

|---|---|

William Hulme, 96th Regiment of Foot Auckland Libraries | |

| Born | 10 May 1788 Halifax, Nova Scotia[1] |

| Died | 21 August 1855 (aged 67) Auckland, New Zealand[2] |

| Buried | Anglican section, Symonds Street Cemetery, Auckland |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Years of service | 1803–1849 |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel |

| Unit | Nova Scotia Fencibles, 1803–[3][4] 1st Regiment (Royal Scots), 1805– 7th Regiment (Royal Fusiliers), 1822– 96th Regiment, 1824–49[5] |

| Commands | New Zealand, 1844–45 |

| Campaigns |

|

| Awards | Army of India Medal, Maheidpoor clasp[8] |

| Spouse(s) |

Jane Wills (m. 1820) |

| Other work | Member, General Legislative Council of New Zealand, 1849[9] Justice of the Peace for the Province of New Ulster, 1849–[9] Postmaster, Province of Auckland, 1854–55[10] Manager, Colonial Bank of Issue, Auckland |

Lieutenant Colonel William Hulme (10 May 1788 – 21 August 1855)[11] was an officer of the 96th Regiment of Foot, British Army.

Early years and family

[edit]William Browne Hulme was born at Halifax, Nova Scotia on 10 May 1788.[1] He was educated at King's College, Windsor, Halifax, Nova Scotia.[3]

His brother, John Lyon Hulme, was born at Manchester, Nova Scotia, on 23 September 1790. He went on to receive a commission in the Corps of Royal Engineers on 24 June 1809; serving in the Peninsular War in Portugal, particularly on the Lines of Torres Vedras, Spain and south-western France from 1810–1814, and the Netherlands campaign from 1815, commanding a division of the pontoon train. They followed the army through to Paris, France, after Waterloo, all under the Duke of Wellington. He also served in Malta and Ireland. John married Mary Hart at St David, Exeter, Devon, on 3 June 1829, and following her death in 1833, retired from service with rank of Brevet Major on 5 December 1835.[12][13] His nephew, Charles Francis Hulme, Ensign, 40th Regiment of Foot, born at Norfolk Island, visited him at home in St Sidwells, Exeter, during the 1861 census.[14]

Their father, also William Brown Hulme (1757–1841), having been transferred from the Drawing Room at the Tower of London was, at the time of their birth, an assistant engineer and draughtsman at Halifax, Nova Scotia. He went on to serve as Sheriff of Sydney County, Nova Scotia, from 12 June 1792;[15] in the 7th Regiment of Foot from 11 October 1796; 6th Irish Brigade from 20 September 1799; 2nd Garrison Battalion with rank of lieutenant from 26 September 1805; and the Royal Staff Corps (RSC) from 1796, with rank of lieutenant from 3 October 1805 to the rank of captain from 31 May 1809. He'd also noted he was severely injured in Spain.[16] The RSC, an army corps responsible for military engineering, were first in the field during the Peninsular War. In 1808, 45 RSC were with Major General Brent Spencer's corps on the south coast of Spain, and 50 more with Sir John Moore's corps.[17][18] The RSC were based at Hythe, Kent,[17] and following marriage to Alice Phillips (1786–1847) at Chelsfield Church, Kent, on 3 August 1811, his sons, William and John, gained two half-siblings—Edward, born at Hythe, Kent, on 18 May 1812, and Maria, born at Hythe, Kent, on 13 August 1813. He retired to half-pay shortly after, on 14 February 1814.[16] Captain W. B. Hulme, late Assistant Quartermaster General, Jersey, died at Tamworth on 8 November 1841.[19]

Half-brother, Edward Hulme, went on to be a surgeon. He left Britain for New Zealand in 1856.

Career

[edit]Upon leaving college,[3] Hulme received a commission as ensign in the newly raised Nova Scotia Fencibles on 23 September 1803.[1]

West Indies

[edit]The first and second battalions of the 1st (Royal) Regiment of Foot had been stationed in the West Indies since 1803. Hulme joined the regiment with the rank of lieutenant on 26 June 1805,[1] but his service in North America soon came to an end on 17 December 1805. A substantially reduced second battalion returned to England in January 1806 to news of the revolt of two Sepoy battalions employed by the East India Company at Vellore and of other troubles. The battalion was immediately ordered to India, reinforced to 1000 men with volunteers from the third and fourth battalions stationed at Bexhill.[20]: 174–175

India

[edit]Hulme's service in the East Indies began on arrival at the Malay Peninsula on 11 September 1807.[1] The Royal Scots battalion was held over at Prince of Wales Island until November, landed at Madras in December, moved out to Walajabad and Bangalore where they remained until 1808, then moved back to Fort St George, Madras.[20]: 176 The battalion took to the field in 1809, then split for the year; the left wing to Hyderabad and the right wing to Machilipatnam, reuniting at Machilipatnam in 1811 in expectation of joining Sir Samuel Auchmuty's expedition against Dutch Java but were diverted to Tiruchirappalli instead, in July.[20]: 182

The regiment was restyled as the 1st Regiment of Foot (Royal Scots) on 11 February 1812. In July, four companies suppressed a mutiny of company troops at Kollam, and returned to Tiruchirappalli. They marched to Bangalore, where in April 1813 Lieutenant Colonel Neill M‘Kellar's right wing joined the force in Maratha country and remained in the field for a year. In April 1814, the left wing of 2nd Battalion marched for Ballari and the right briefly formed part of force in southern Maratha country. The two wings met up in Bellari in May, then moved on to Hyderabad and Achalpur where they were employed against Pindari marauders into 1817.[20]: 183, 191, 202–203

Pindari freebooting had reached a point where, in about August 1817, under the governorship of Francis Rawdon-Hastings, the largest armies in India to date were assembled to isolate and disband Pindari society wherever it could be found, as well as deal to hostile intentions of a rising Maratha Confederacy—the Grand Army commanded by Rawdon-Hastings and the Army of the Deccan commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Hislop. The Army of the Deccan was a distinct force consisting of seven divisions, not including irregular infantry or horse of Nizam, Pune or Nagpur, amounting to 54,465 rank and file, of which of the flank companies of the Royal Scots, some 171 rank & file, formed part of the First Division under Hislop.[21]: Appx. 55–59 [22]: 113 [23]

Third Anglo-Maratha War

[edit]Mahidpur

[edit]Stationed at Jalna, Captain Hulme's two Royal Scots flank companies, with two regiments of native cavalry and four guns, marched out north-northeast on 11 October 1817, to join 1st division headquarters at Harda on 22 October. Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Fraser's Royal Scots companies marched out east-northeast on 15 October for Mehkar but were redirected to assist the British force under attack at Nagpur. Joining the 2nd division at Amravati on 7 November, they moved on to take part in the Battle of Sitabuldi, Nagpur. Meanwhile, Hulme and his flank companies, moving northwest, crossed the Narmada River in flat-bottomed boats with the 1st division on 30 November, arrived at Piplya on 8 December and marched on to encamp near Ujjain, some 28 miles (45 km) from Mahidpur. The 1st and 3rd divisions of the army encamped there on 12 December. [20]: 221–222 [22]: 47

On 14 December they marched for Mahidpur where the army of the Marahaja of Indore, Malhar Rao Holkar III, Hari Rao Holkar and Bhima Bai Holkar, had assembled. Brigadier General Sir John Malcolm, as political officer, received Holkar's representatives on 15 December but dismissed them after some four days of unsuccessful negotiations and prepared for attack.[22]: 47

On the morning of 22 December, Holkar's army were found arranged in two lines on the high ground about the ruined hilltop village of Dubli about half a mile beyond the ford on the Shipra River. Daunting in appearance, the first line of infantry numbering some 5,000 stretched across from their left toward the Shipra, near Mahidpur, to a river on their right, and were covered in front by an artillery line of some 76 guns. Beyond that, a second line of a dense force of 30,000 horse filled the plain. The British forces numbered under 5,500, of which the 1st Brigade, infantry of the line, under Lieutenant Colonel R. Scott, Madras European Regiment (MER), was made up of Royal Scots flank companies under Captain Hulme, the Madras European Regiment under Major Andrews, 1/14th Madras Native Infantry (1/14th MNI) under Major Smith and 2/14th Madras Native Infantry (2/14th MNI) under Major Ives.[22]: 49–51 [24]: 454

Crossing the river at the ford, they came under cannon fire and formed up under shelter of the opposite bank, along with Hislop and staff. Malcolm ordered Hulme's flank companies, the MER and 2/14th MNI to move up and form on top of the bank.

Hulme's flank companies were tasked with leading the attack toward the right on Holkar's left flank and at Dubli. Steady but determined, suffering severe injuries from grape and chain shot, a bayonet charge through Holkar's artillery cleared Dubli and drove the flank's infantry to flee; Holkar's artillerymen carrying on their deadly cannonade to the last. Holkar's left flank were pursued along the river bank to their camp, which when attacked by the Royal Scots caused them to retreat across the river.[25]: 113–117 [22]: 50–51 Holkar's right flank was overpowered at the same time by infantry and cavalry, and the centre, finding both flanks turned, gave way on the appearance of a brigade ascending from the river. Holkar's horse had also fled in the action, Holkar's artillery turning some guns and firing a salvo upon them as they left.[22]: 51

The engagement, which ended at 1:30 pm had lasted some two or three hours.[25]: 117 Malcolm, thereafter, pursued Holkar to Mandsaur where a treaty was settled on 6 January 1818, defining the state's territories that were to be defended against all enemies. In general orders of 23 December 1817, Hislop observed:

The undaunted heroism displayed by the flank companies of the ROYAL SCOTS in storming and carrying, at the point of the bayonet, the enemy's guns on the right of Lieut.-Colonel Scot's brigade was worthy of the high name and reputation of that regiment. Lieutenant M‘Leod fell gloriously in the charge, and the conduct of Captain Hulme, Captain M‘Gregor, and of every officer and man belonging to it entitles them to his Excellency's most favourable report and warmest commendation.[20]: 222

With Sir John Malcolm's support, Hulme was awarded the rank of Brevet Major on 23 December 1817.[26] Battle honours of Nagpore and Maheidpoor were added to the 1st Regiment (Royal Scots) colours on 26 February 1823.[20] The loot seized during this campaign was enormous, and led to bitter argument over prize money for many years.[27][28][29] Following approval of the Army of India Medal (AIM) in 1851, Hulme, then retired in New Zealand, was amongst thirty-eight recipients with the Maheidpoor clasp, presented to officers and men of 1st Regiment (Royal Scots), 2nd Battalion, who were specially mentioned in the Commander-in-Chief's orders.[30]: 87–88

-

Battlefield of Mahidpur from the Shipra River, December 1817.

-

Plan of the Battle of Mahidpur, 21 December 1817.

-

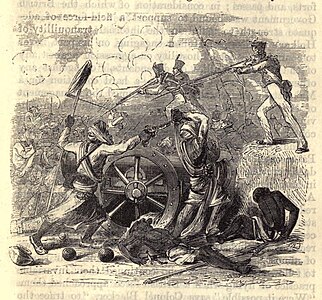

Capturing Holkar guns.

-

Plan of the encampment at Mahidpur, 21 December 1817.

Thalner Fort

[edit]Marching from Mahidpur, the army stopped over at Indore, 2–6 February, and crossed Narmada River on 13 February. At Khargone they were joined by Lieutenant Colonel Heath and his detachment of Madras European Regiment from Handia on 18 February, and marched on down Sendhwa ghat.[31]: 419 They received Sendhwa fort, ceded under the Treaty of Mandsaur, on 23 February.[24]: 228 Expecting friendly territory, the baggage column moved on ahead of the troops to Panakhed, Karwand and the Tapti river ford. Reports that the Kiladar of Thalner intended to resist ceding the fort were not credible.[32]

Miles ahead, a sick officer carried by palanquin, making for encampment across the river, was fired upon as he passed Thalner Fort, requiring him to turn back. Shot was also fired at the baggage column entering the town.[25]: 144 [24]: 228 [31]: 419–420 Having just heard of the intention to resist, Hislop sent Lieutenant Colonel Valentine Blacker, a Madras Engineers officer and company of light infantry to reconnoitre. At about 7:00 am, he sent a message to the Kiladar requiring him to open the gates and surrender, or be hung. With no reply, it was unclear if it had been received.[24]: 228 [25]: 143–154 [31]: 420 [33]: 254 [22]: 68

The fort was chiefly garrisoned by Arabs. A deep ravine surrounded the fort's mound. On the western side, commanding river and fords, its terre-plein was about 70 feet above the riverside; the walls on top were no higher than 16 feet. The interior sloped to the eastern entrance complex of turrets, ramparts and gates at descending levels.[25]: 145 Blacker's reconnaissance revealed no guns on the western face, so camp was set about a mile northwest on 27 February.[25]: 143–154

Hislop resolved to attack. Artillery were brought up at 10:00 am; 6-pounders, 5½-inch howitzers and rockets kept up fire on the entrance complex and into the fort.[34]: 54 [31]: 420 [25]: 146–147 The Storming Party under Major John Gordon, Royal Scots, consisting of the flank companies under Captain Hulme and Madras European Regiment under Captain Maitland, stood by.[25]: 146–147 [35] As the day proceeded, with support of the Rifle Corps and the 3rd Light Infantry, they moved up with two guns to shelter in a ravine south-east of the fort.[31]: 420 [25]: 143–154 [24]: 230

Artillery fire on the gates, and the likelihood of assault, troubled the garrison. The Kiladar called for terms at about 4:00 pm, and when requested to open the gates and unconditionally surrender, he promised to comply.[32][33]: 254 [22]: 68 [24]: 230–231 When a white flag appeared on the fort at about 5:00 pm, some pioneers approached the gate unopposed, and finding it barred, managed to enter through an opening made between the right wall and gate-frame. With the flag still flying and Arabs appearing on the walls, Gordon, his storming party and other officers entered the first gate, passed through the second gate and stopped at the third.[25]: 147–148 Captain Peter MacGregor, Royal Scots, commanded the grenadiers. At the third gate, the Kiladar, with ten or eleven banyans and artificers, came out and surrendered to the pioneer officer. The Kiladar told the Adjutant General, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Conway, that, "What ever fault may have been committed, I am the guilty person, but let the garrison know what terms they are to have", and was sent on to headquarters.[25]: 148–149 Blacker later supposed that: "It is possible their indecision arose from a division in their councils; and the departure of the Killedar from among them supports this conclusion".[24]: 232

Lieutenant Colonel MacGregor Murray, Gordon, MacGregor and some Royal Scots moved on through the fourth gate to the stop at last fifth gate with its wicket ajar. Talk of terms was carried on but, without an interpreter acquainted with the customs, not mutually understood.[24]: 231 Murray pushed his way through the wicket, sword undrawn as friendly gesture to the few Arabs in front of the gate, followed by Gordon and three grenadiers.[24]: 231 The staff officer outside gave an order to disarm the Arabs, strongly repeated.[25]: 149 Murray put out his hand out inviting an Arab to surrender his matchlock but the fellow withdrew. He then put his hand on the hilt his sword and the grenadiers took to seizing matchlocks. Taking offense, the Arabs called out in their language, "Their honour and their faith", drew daggers and set upon the party, killing Gordon and the three grenadiers.[25]: 150 [36] Murray fell wounded toward the wicket, fending off with his sword. As the Arabs closed the wicket, a grenadier on the outside thrust his musket through the gap whilst Lieutenant Colonel Mackintosh, Commissariat, and Captain M‘Craith, Madras Pioneers, forced the door open. M‘Craith grabbed Murray with one hand and dragged him through whilst warding off blows with his sword in the other.

The head of the storming party fell back in confusion. Though the garrison had advantage of the gate's kill zone, MacGregor and thirty or forty of his grenadiers re-entered unopposed, and finding the wicket still open, poured fire through it to clear a way for the party to enter. As the gates opened, the late Major Gordon's storming party, Hulme and Maitland now commanding, poured in and put the garrison, said to number from 180 to 300, to the sword.[1][37] Many Arabs sheltered in their houses for defence; some collected on one of the towers and made a feeble resistance; others threw themselves off the wall to the river and were dashed. Apparently, only two escaped. MacGregor was killed in the assault; Lieutenant John MacGregor severely wounded defending his brother's body; Lieutenant Alex Anderson, Madras Engineers, and Lieutenant Chauval, 1/2nd Madras Native Infantry, were severely wounded.[25]: 150 [33]: 255 [20]: 225

The fort was taken that evening, 27 February 1818. The Kiladar was hung from a tree on the fort's flagstaff tower; an officer relieving him of living through it with a musket ball.[25]: 151 Hislop noted: "Whether he was accessory or not to the subsequent treachery of his men, his execution was a punishment justly due to his rebellion in the first instance, particularly after the warning he had received in the morning."[33]: 254 [38]: 184–185 Carnaticus commented in 1820:

The general impression through the British camp was, that we had acted treacherously on this occasion; but the execution of the Killedar, a Bramin and nearly related to some of the first families in the country, and his having been exposed naked from the walls, branded our name with an idea of barbarity and injustice, that in that quarter of India will not be easily effaced or forgotten. Sir T. Hislop supposed, or more probably was led to think so by some of those about him, that the garrison acted treacherously upon the head of our party, in first admitting them through the wicket, and then setting upon them; but, however Sir T. Hislop's well-known humanity and moderation may acquit him (and we have good reason to know, that he was not the most morally culpable in that transaction) of a wanton or premeditated shedding of blood, still, in the affair of Talnair, his name as the chief commander must remain attached to it, and surely not under the most flattering colours.[25]: 153

The army left a detachment of the 16th Light Infantry at Thalner.[25]: 154 In pursuit of Baji Rao II they crossed the Tapti and reached Parola on 6 March, then to Porlah, Godavari River, where it merged with the 2nd division under Brigadier General John Doveton. Two flank companies and three battalion companies of Royal Scots were directed to Hyderabad.[20]: 225 Hislop left for the Aurangabad on 20 March where he issued last orders on 31 March.[31]: 421 Hulme took leave from 30 November 1819,[1] shortly before the battalion quit Walajabad, near Madras, for Tiruchirappalli.[20]: 235

-

Sketch of the attack on the fort of Thalner, 27 February 1818.

-

Plan of the assault of the fort of Thalner, 27 February 1818.

Kalakriti Archives -

Plan and section elevation of Thalner's gates, 27 February 1818.

-

Capt M‘Craith drags Lt Col Murray clear of the wicket whilst warding off blows with his sword.

-

Thalner Fort, 2017.

-

British tombs erected to the memory of the officers killed, Thalner Fort, 2017.

Home and abroad

[edit]Returned to England, Hulme married Jane Wills (1798–1872), daughter of John Wills, Proctor, Doctors' Commons, London, at St Mary's Church, Newington, Middlesex, on 22 April 1820. He returned briefly to India from 14 September 1820 to 16 May 1821, his battalion then stationed in Tiruchirappalli since January 1820. Their first child, Jane Mary Hulme, was born at Newington on 9 June 1822.[1] In July that year, Major Hulme exchanged places with Captain Matthew Ford, to be Captain of the 7th Regiment, Royal Fusiliers.[39]

Several years later, from 29 January 1824, Brevet Major Hulme was transferred from the 7th Regiment, Royal Fusiliers, to be Captain of the new 96th Regiment of Foot[40] then being reformed at Salford Barracks, Manchester, in continuation of preceding regiments of the same designation and battle honours—Peninsular, Egypt and the Sphinx. They were immediately sent from Liverpool in June–August 1824 to garrison Hulme's hometown of Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Hulme was stationed with the 96th Regiment at Halifax from September 1824, and in Bermuda from September 1825, where a son, William, was born in October 1825.[1] Another son, John Wills, though, was born on 4 April 1827; baptised at St David, Exeter, Devonshire, 12 May 1827.[1] They returned to Halifax in September 1828, until 31 December 1829. A daughter, Maria Russell, was born there in 1832.[1] He was promoted to rank of regimental major on 9 March 1834. The 96th Regiment returned home to England in September 1835.[41]

Landed at Gosport, Hampshire, in 1836, the regiment marched to Gravesend in October, then sailed to station at Leith, Edinburgh Castle and Greenlaw in Scotland. They moved to Glasgow in November, then to Enniskillen and Dublin in Ireland a year later. Back to England, they were stationed at Liverpool and Lancaster.[42] Hulme was promoted to rank of brevet lieutenant colonel on 10 January 1837.[41] By 1839 the 96th were stationed at Liverpool, Wigan and Haydock with headquarters at Bolton le Moors, Salford Barracks in December 1839 and later Chatham, Kent. Since 21 June, detachments of the Regiment were made ready for travel to New South Wales, assigned to escorting convicts. The 1st Detachment departed from Sheerness on 4 August. The 2nd Detachment under Hulme proceeded from Bolton on 29 August 1839, for embarkation on board the barque Canton, departing Portsmouth on 22 September.[43][42]

Australia

[edit]After a 112 day voyage, Hulme, family, 2nd Detachment of the 96th and prisoners arrived at Hobart, Van Diemen's Land, on the 12 January 1840.[44]

Norfolk Island penal settlement

[edit]Though assigned to Launceston, in March he accompanied Captain Alexander Maconochie to Norfolk Island to relieve the 50th Regiment and command the troops there.[45][46] Another son, Charles Francis, was born at Norfolk Island on 9 March 1842.[47] The Hulmes and the detachment of the 96th departed Norfolk Island by the Duke of Richmond on 28 February, arriving at Launceston, Van Diemen's Land, on 11 March 1844.[48] With Hulme now appointed command of troops in New Zealand, they left Launceston for that country on 23 March 1844.[49]

-

Norfolk Island convict settlement, c. 1839. Artist: Thomas Seller

National Library of Australia

New Zealand

[edit]Relieving Major Thomas Bunbury and the 80th Regiment in New Zealand, Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Hulme[50] arrived in Auckland on 14 April 1844, from Launceston, Van Dieman's Land, on the Marian Watson, along with Lieutenant Edward Barclay, Assistant Surgeon Stewart, and 59 soldiers of the 96th Regiment. Major Robertson, Ensign John Campbell and 55 soldiers and family's had arrived by the Water Lilly on the same day.[51] His military career is perhaps better known for his part in the Flagstaff War, 1845–1846, the first Anglo-Māori war.

Flagstaff War

[edit]Otuihu

[edit]Governor Robert FitzRoy gazetted a proclamation of martial law within 60 miles of Russell[52] as well as notice of 26 April, stating that: "During the continuance of war, no natives may approach the Ships, the Soldiers, or encampment at the Bay of Islands,—wherever placed; without having a Missionary, or a Protector, with a white Flag, with them, lest the Soldiers should mistake friends for enemies, and fire upon them in error."[52]

HMS North Star had sailed for the Bay of Islands on 23 April. The barque Slains Castle with the 58th Regiment under Major Cyrprian Bridge, brigantine Velocity and schooner Aurora with the 96th Regiment under Lieut. Colonel Hulme and about 50 volunteers under command of Cornthwaite Hector, sailed out of Auckland for the Bay of Islands on 27 April, anchoring off Kororāreka on the 28 April. After consultation with Sir James Everard Home, HMS North Star at anchor, about re-establishing authority there, the Grenadier company of the 58th Regiment were landed, a proclamation was read, the Union Jack was hoisted under a 21 gun salute from HMS North Star, the yards were manned and three cheers from the troops on shore were answers by the sailors and troops on board the ships.

Hulme later reported to FitzRoy that in obedience with FitRoy's instructions, he "prepared to attack the rebel chiefs, and to destroy their property". On the morning of 29 April. HMS North Star, Velocity, Slains Castle and Aurora moved off for Waikare Inlet but light winds slowed their five mile voyage to a midnight anchorage off Otuihu, the exposed pā of a supposed rebel chief, Pomare.[53] Hulme reported:

At daylight, I was much surprised to see a white flag flying in Pomare's pah; but as the proclamation only authorized loyal natives to shew it, I could not recognise it as an emblem of peace from a supposed rebel.—The troops commenced disembarking, and when landed, I sent two Interpreters with a message into the pah, to desire Pomare to come to me directly; his answer was,—"The Colonel must come to me." He sent the same answer to a second message. One of the interpreters now offered to remain a hostage in the pah—this I would not hear of. I then sent my final message to Pomare, that if he did not come to me in five minutes, I would attack his pah, this threat induced Pomare to come.[53]

Hulme's two interpreters were Joseph Merrett and Edward Meurant. Merrett explained to the Auckland Times in May:

Both Mr. Meurant and myself used every argument to persuade him to trust to the word of our commanding officer—that no one would hurt him. I had never been told officially that Pomare was to be taken a prisoner, and must go, as such, to the Governor, on board the "North Star,"—nor did I for a moment believe that Colonel Hulme, in the presence of his officers, would promise the chief safety, and, in the face of that promise, make him a prisoner of war. I had told Pomare that the word of my officer was the word of a gentleman, and that it would not be broken. While Mr M. and myself were in the midst of the natives, the troops were seen advancing up to the pah (who ever heard of an armed body walking, under a flag of truce, into an enemy's encampment with the intention of destroying it—a flag of truce at the same time flying the forces of the latter—and making a hostile advance while their own interpreters were offering proposals from one party to the other)

My instructions were to bring the chief to the Colonel, and he had agreed to accompany me, but this movement of the troops, in a moment gave the signal of action on the part of the natives. A moment more and a destructive fire would have been opened, and our men must, have suffered severe loss, I ran past the natives, and told the Officer in command, of all the circumstances, the advance was then stopped. Pomare went down with Mr. Meurant and myself, leaving the soldiers and natives within pistol shot of each other, each waiting for the signal to commence the combat. When Pomare reached the troops some conversation took place between the Colonel and him, through the interpreters…[54]

Hulme explained to Pomare that his conduct had been very bad; that he must go on board North Star, and accompany Hulme to Auckland to account for it to the Governor.[54] Merrett continued:

...and to my great surprise, in a few minutes a file of soldiers wore ordered to surround Pomare and make him prisoner. I accompanied him on board the North Star at his request, he seemed very much dispirited, and surprised at the sentinels being placed over him; and the tears came in his eyes while speaking of his wife and children, he said he had trusted to the faith of Europeans whom he had always protected; but that he had been taken treacherously. I told him he could not blame me, and repeated literally the instructions I had received from Colonel Hulme; he said he would not blame me, and gave me his ammunition box as a proof of his confidence in what I had said,—he much wished me to stay with him on board, and go with him to the Governor; he wrote a letter to his people telling them to retire to their homes peaceably, as he was a prisoner and security for their good behaviour; he wished to have his wife and children on board. In the evening his pah was plundered and burnt, and an attempt was made by the commanding Officer to cut off the retreat of his people, and disarm them; but it was delayed too long, and the natives escaped.[54]

Thomas Bernard Collinson, RE, commented in 1853, that: "It was unnecessary to destroy his pah; but there is no doubt Colonel Hulme was actuated by feelings of humanity. The character for gallantry he obtained, even during this short campaign, is a sufficient proof of that."[7]: 54–58

-

Whētoi Pōmare. Artist: Gottfried Lindauer.

-

Hulme burns Otuihu whilst Pōmare is held on board HMS North Star, 30 April 1845. Artist: John Williams, 58th Regt, 1845.

Alexander Turnbull Library

Puketutu

[edit]Hulme also commanded the military forces during the attack on Heke's pā, Te Kahika, at Puketutu (sometimes called Te Mawhe and Okaihau) on the northeast side of Lake Ōmāpere.[55] In May 1845 Heke's pā was attacked by troops from the 58th, 96th and 99th Regiments with Royal Marines and a Congreve rocket unit.[56] In parallel operations elsewhere, on 7 May, Lieutenant George Phillpotts, RN, with seamen of HM Ships North Star and Hazard, burnt five small villages belonging to Heke, broke up two large canoes and brought off two large ones. On 9 May, a party under Mr. Lane broke up two large canoes and carried off four boats taken from Kororāreka.[57]

The military forces arrived at Heke's pā at Puketutu on 7 May 1845. Lieutenant Colonel Hulme and his second in command Major Cyprian Bridge made an inspection of Heke's pā and found it to be quite formidable.[58] Lacking any better plan they decided on a frontal assault the following day. Te Ruki Kawiti and his warriors attacked the colonial forces as they approached the pā, with Heke and his warriors firing from behind the defences of the pā. There followed a savage and confused battle. Eventually the discipline and cohesiveness of the British troops began to prevail and the Māori were driven back inside the pā. But they were by no means beaten, far from it, as without artillery the British had no way to breach the defences of the pā. Hulme decided to disengage and withdraw his force to Kerikeri.[59] They transferred to the North Star, Slains Castle, Velocity and Albert, and sailed for Auckland on Sunday, 11 May.[60][61] On 15 May, the remaining force of Major Bridge, 200 men and 8 marines, along with Tāmati Wāka Nene and his warriors, attacked Te Kapotai pā at Waikare by night; the inhabitants evacuating the pā with little resistance. Property said to have been stolen from Kororāreka and elsewhere was believed to have been concealed in dense bush, making it impossible to find. Phillpotts took away several boats.[62]

From the arrival of additional troops in June 1845, Hulme was superseded in command of the forces in New Zealand by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Despard, 99th Regiment,[63] a soldier who did very little to inspire any confidence in his troops.[56]

-

Hone Heke's pā, Puketutu, under attack by British forces, 8 May 1845. Artist: Copy after John Williams, 58th Regt, 1845.

State Library of New South Wales -

Hone Heke's pā, Puketutu, under attack. Artist: John Williams, 58th Regt, 1845.

Alexander Turnbull Library

Later life

[edit]In 1846 he purchased a house in Parnell, Auckland, which became and is still known as Hulme Court. While not open to the public, this is on the New Zealand Historic Places register and is one of the oldest documented houses in Auckland still standing.[64]

Australia

[edit]Based in Hobart, Van Diemen's Land, with his troops, since arrival of the ship Java on 19 December 1846,[65] Hulme advanced from Brevet Lieutenant Colonel to Lieutenant Colonel without purchase in 1848.[66] He then retired from soldiering in 1849 and moved back to New Zealand.[37]

New Zealand

[edit]Legislative Council

[edit]In July 1849, Governor George Grey, appointed Hulme to member of the General Legislative Council.[67] That year, Hulme introduced the idea of a motion and ordinance in favour of enabling Maori land in the northern district of New Zealand to be used for cattle grazing by squatting. "Nothing, he thought, would tend so much to the general good and welfare of New Zealand as the opening up of its lands to the occupation of European settlers and squatters." In response: "The Governor said that the resolution as it now stood could not be entertained by the Council—but he thought that they might readily adopt a different one, which might answer the ends aimed at, and be less objectionable. As it stood he could not advise its adoption, for this reason that it involved a question that was one of universal interest for the whole of New Zealand, South as well as North; and although the General Legislative Council of the whole islands had power vested in it to adopt resolutions on this subject, yet as this Council did not represent the whole islands, it could not entertain a subject affecting the entire country."[68]

Post Office

[edit]Hulme was appointed by Governor George Grey as the first Postmaster for the Province of Auckland from 1 January 1854[69] but received less support in the idea of an appointment to Postmaster-General for New Zealand.[70]

Death

[edit]William Hulme died on Tuesday, 21 August 1855, in his 68th year and was buried with military honours in Symonds Street Cemetery on Friday, 24 August. The New-Zealander wrote:

The late Lieut. Col. Hulme was a fine specimen of a thorough English soldier; intrepid and cool on all occasions. In 1849 he sold out of the service, and returned to Auckland, where to the hour of his death, he was all along held in the highest estimation as an upright and honourable colonist.[37]

His former residence in Parnell, now known as Hulme Court, is identified as a Historic Place Category 1 by Heritage New Zealand.[71]

-

Hulme Court, Parnell, Auckland, 2022.

-

96th Regt full dress coatee worn by Lt Col William Hulme.

Auckland Museum -

Cross belt and pouch worn by Lt Col William Hulme.

Auckland Museum -

A pair of Gill and Knubley flintlock duelling pistols, circa 1790, possibly owned by Lt Col William Hulme.

Auckland Museum -

Shouting their war-cry, the British charged the breach. Artist: J R Skelton, 1908.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k WO 25/804/4: Folio 6. Statement of Services of Bt Major Wm Hulme of the 96th Regiment of Infantry with a Record of such Particulars as may be useful in case of his Death, The National Archives, p. 7

- ^ "Died". The Southern Cross. Vol. 12, no. 851. 24 August 1855. p. 2.

- ^ a b c Eaton, Arthur Wentworth Hamilton (1891). The Church of England in Nova Scotia and the Tory Clergy of the Revolution. New York: Thomas Whitaker. p. 209.

- ^ War Office (1805). A List of All the Officers of the Army and Royal Marines on Full and Half-pay with an Index: and a Succession of Colonels. London: War Office. p. 362.

- ^ a b c Groves, Percy (1903). Historical Records of the 7th or Royal Regiment of Fusiliers: Now Known as the Royal Fusiliers (the City of London Regiment), 1685–1903. Guernsey: Frederick B. Guerin. p. 359.

- ^ "Original Correspondence: To the Editor of the Auckland Times. Narrative of Proceedings Leading to the Capture of Pomare". Auckland Times. Vol. 3, no. 124. 24 May 1845. p. 3.

- ^ a b c Collinson, Thomas Bernard (1853). "2. Remarks on the Military Operations in New Zealand" (PDF). Papers on Subjects Connected with the Duties of the Corp of Royal Engineers. New Series 3. London: John Weale: 5–69.

- ^ "Army of India Medal—Royal Scots (name misspelt: Hulure, William, Captain)". Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Government Gazette: Legislative, Council Chamber". The New-Zealander. Vol. 5, no. 333. 26 July 1849. p. 4.

- ^ "The Southern Cross". Vol. 11, no. 705. 31 March 1854. p. 2.

- ^ McKenzie, Joan (11 April 2011). "Burrows House, Parnell". New Zealand Historic Places Trust. p. 3. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ WO 25/3913 Statement of Services of John Lyon Hulme of the Royal Engineers with a Record of such Particulars as may be useful in case of his Death, p. 18

- ^ "M.G.S. and N.G.S. Medals to the Royal Engineers and the Royal Sappers & Miners: Lot 402. Military General Service 1793-1814, 2 Clasps, Nivelle, Nive (J. Hulme, Lieut. R. Engrs.)". Noonans. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ England and Wales Census, 1861

- ^ RA GEO/ADD/18/44-45 Appointment of William Brown Hulme as Sheriff of the County of Sydney, Nova Scotia (PDF), Royal Archives, Windsor – via Royal Collection Trust

- ^ a b WO 25/762/217 Services of Officers on Full and Half Pay: William Brown Hulme. Regiments: 7th Fusiliers; Irish Brigade; Royal Staff Corps. Dates of Service: 1796–1804, 1828, p. 217

- ^ a b Garwood, F. S. (1943). "The Royal Staff Corps, 1800–1837" (PDF). The Royal Engineers Journal. 57 (June). Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers: 82–96.

- ^ "Wellington's Dispatches: July 21st, 1808". War Times Journal. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ "Deaths". The New Army List for January 1842. London: John Murray. 1 January 1842. p. 242.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cannon, Richard (1847). Historical Record of the First Regiment of Foot: Containing an Account of the Origin of the Regiment in the Reign of King James VI. of Scotland, and of its Subsequent Services to 1846. London: Parker, Furnivall & Parker.

- ^ Hislop, Thomas (1820), The Memorial of Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Hislop, Bart. G. C. B. late Commander-in-Chief of the Army of Fort St. George in the East Indies, and Commander-in-Chief of the Army of the Deccan in the late Mahratta war, acting for himself in the later capacity, as likewise on behalf of the said Army of the Deccan, London

- ^ a b c d e f g h Burton, Reginald George (1910). The Mahratta and Pindari War Compiled for General Staff, India. Simla: Government Monotype Press.

- ^ McEldowney, Philip (1966). Pindari Society and the Establishment of British Paramountcy in India (Thesis). University of Wisconsin.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Blacker, Valentine (1821). Memoir of the Operations of the British Army in India: During the Mahratta War of 1817, 1818, & 1819. London: Black, Kingsbury, Parbury, and Allen.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Carnaticus (1820). Summary of the Mahratta and Pindarree Campaign During 1817, 1818, and 1819, Under the Direction of the Marquis of Hastings: Chiefly Embracing the Operations of the Army of the Deckan, Under the Command of His Excellency Lieut.-Gen. Sir T. Hislop, Bart. G.C.B. with Some Particulars and Remarks. London: E. Williams.

- ^ J. A., ed. (1832). The Royal Kalendar: and Court and City Register, for England, Scotland, Ireland, and the Colonies for the Year 1832. London: Suttaby & Co. p. 196.

- ^ "Deccan Prize Money". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Vol. 14. Parliament of the United Kingdom: HC. 6 August 1832. col. 1136–56.

- ^ Kinloch, Alfred (1864). Abridgement of the Report of the Proceedings in the Case of the Deccan Prize Money. London: Alfred Kinloch.

- ^ Great Britain. Army. Army of the Deccan, 1817, 1818 (1824). The Claims of the Army of the Deccan. London: Thomas Davidson.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Steward, W. Augustus (1915). The A.B.C. of War Medals and Decorations: Being the History of the Manner in Which They Were Won, and a Complete Record of Their Award: Their Characteristics: How They are Named and How They are Counterfeited (PDF). London: Stanley Paul & Co.

- ^ a b c d e f Neill, James George Smith (1843). Historical Record of the Honourable East India Company's First Madras European Regiment Containing an Account of the Establishment of Independent Companies in 1645; Their Formation into a Regiment in 1748; and its Subsequent Services to 1842. London: Smith, Elder and Co.

- ^ a b An Eye-Witness (May 1820). "Storm and Fall of Talnair". The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and Its Dependencies. 9 (53). London: Black, Kingsbury, Parbury, & Allen: 448–451.

- ^ a b c d Papers Respecting the Pindarry and Mahratta Wars, Court of Proprietors of East-India Stock, 1824

- ^ Lake, Edward (1825). Journals of the Sieges of the Madras Army, in the Years 1817, 1818, and 1819. With Observations on the System, According to which Such Operations Have Usually Been Conducted in India, and a Statement of the Improvements that Appear Necessary. London: Kingsbury, Parbury, and Allen.

- ^ Madras Presidency. Madras Artillery Records. Vol. 2. p. 227.

- ^ Stewart-Murray, Katharine Marjory; MacDonald, Jane C. C., eds. (1908). A Military History of Perthshire. Vol. 1. Perth: R. A. & J. Hay. pp. 504–505.

- ^ a b c "Funeral of the Late Col. Hulme". New Zealander. Vol. 11, no. 977. 25 August 1855. p. 2.

- ^ Baldwin, Cradock and Joy (1819). "XVII. East India Affairs". The Annual Register or a View of the History, Politics and Literature for the Year 1818. London: Baldwin, Cradock and Joy. pp. 181–190.

- ^ "The London Gazette". No. 17832. London. 6 July 1822. p. 1115.

- ^ "The London Gazette". No. 17999. London. 7 February 1824. p. 212.

- ^ a b Hart, Henry George (1839). The New Annual Army List. London: Smith, Elder and Co. p. 148.

- ^ a b "Libraries and Leisure: Museum of the Manchester Regiment". Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council. 2024. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ "Record of Services of 96th Regiment", Records of the Manchester Regiment (63rd & 96th Regiments as filmed by the AJCP) [microfilm]: [M2080], 1828–1953./Series 2/File 2/ 1/6/Item ff. 11-[36], p. 12, 1839

- ^ "Ship News". Colonial Times. Vol. 27, no. 1233. 14 January 1840.

- ^ "Van Diemen's Land". Adelaide Chronicle and South Australian Advertiser. Vol. 1, no. 16. 24 March 1840 – via Trove.

- ^ "Fete at Norfolk Island". The Sydney Herald. Vol. 10, no. 1008 Supplement. 1 July 1840. p. 1.

- ^ "Birth". The Sydney Herald. Vol. 13, no. 1546. 3 May 1842. p. 3.

- ^ "Hobart Town". Launceston Examiner. Vol. 3, no. 184. 27 March 1844. p. 5.

- ^ "Ship News". The Cornwall Chronicle. Vol. 10, no. 521. 16 March 1844. p. 2.

- ^ Hart, Henry George (1846). The New Annual Army List for 1846. Vol. 7. London: John Murray. p. 249.

- ^ "Shipping List". The Southern Cross. Vol. 2, no. 53. 20 April 1844. p. 2.

- ^ a b "Bay of Islands". The Auckland Times. Vol. 3, no. 121. 6 May 1845. p. 2.

- ^ a b "Narrative of Events at the Bay of Islands". New Zealander. Vol. 1, no. 1. 7 June 1845. p. 2.

- ^ a b c "Original Correspondence: To the Editor of the Auckland Times. Narrative of Proceedings Leading to the Capture of Pomare". The Auckland Times. Vol. 3, no. 124. 24 May 1845. p. 3.

- ^ "Puketutu and Te Ahuahu – Northern War". Ministry for Culture and Heritage – NZ History online. 3 April 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ a b Raugh, Harold E. (2004). The Victorians at War, 1815–1914: An Encyclopedia of British Military History. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 225–226. ISBN 9781576079256.

- ^ "Bay of Islands". The Wellington Independent. Vol. 1, no. 26. 28 June 1845. p. 4.

- ^ Reeves, William Pember (1895). "F. E. Maning "Heke's War … told by an Old Chief"". The New Zealand Reader. Wellington: Samuel Costall. pp. 173–179.

- ^ Cowan, James (1922). "Chapter 6: The Fighting at Omapere". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period. Vol. 1: 1845–1864. Wellington: R.E. Owen.

- ^ "New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian". The New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian. Vol. 1, no. 37. 21 June 1845. p. 2.

- ^ "Another Account". The New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian. Vol. I, no. 37. 21 June 1845. p. 4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZSCSG18450621.2.17.

- ^ "Bay of Islands". The Wellington Independent. Vol. 1, no. 26. 28 June 1845. p. 4.

- ^ "Local Intelligence". Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle. Vol. 4, no. 170. 7 June 1845. p. 54.

- ^ "Hulme Court". New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero. Heritage New Zealand. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ "Shipping Intelligence". The Maitland and Hunter River General Advertiser. Vol. 4, no. 258.

- ^ "Emigrant Ship Ocean Monarch Burnt at Sea". The Sydney Morning Herald. Vol. 24, no. 3609. 12 December 1848. p. 3.

- ^ "The New-Zealander". Vol. 5, no. 333. 26 July 1849. p. 2.

- ^ "General Legislative Council. Tuesday, August 7, 1849. (continued from our last.) Crown Lands' Bill". The New-Zealander. Vol. 5, no. 340. 11 August 1849. p. 2.

- ^ "The Southern Cross". Vol. 11, no. 705. 31 March 1854. p. 2.

- ^ "General Assembly. House of Representatives. Friday Evening, Sept. 8, 1854". The Southern Cross: Supplement. Vol. 11, no. 763. 20 October 1854. p. 1.

- ^ "Hulme Court". Heritage New Zealand. Retrieved 1 January 2025.

- 1788 births

- 1855 deaths

- Pre-Confederation Nova Scotia people

- University of King's College alumni

- Military personnel from Halifax, Nova Scotia

- Royal Scots officers

- Royal Fusiliers officers

- 96th Regiment of Foot officers

- British military personnel of the Third Anglo-Maratha War

- History of Norfolk Island

- British military personnel of the New Zealand Wars

- 19th-century New Zealand military personnel

- Flagstaff War

- Members of the New Zealand Legislative Council (1841–1853)

- Burials at Symonds Street Cemetery

- 19th-century British Army personnel