Jews

יְהוּדִים (Yehudim) | |

|---|---|

The Star of David, a common symbol of the Jewish people | |

| Total population | |

| 15.8 million Enlarged population (includes anyone with a Jewish parent): 20 million[a][2]  | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Israel (including occupied territories) | 7,300,000–7,455,200[3] |

| United States | 6,300,000–7,500,000[3] |

| France | 438,500–550,000[3] |

| Canada | 400,000–450,000[3] |

| United Kingdom | 312,000–330,000[2][4] |

| Argentina | 171,000–240,000[2][4] |

| Russia | 132,000–290,000[2][4] |

| Germany | 125,000–175,000[2][4] |

| Australia | 117,200–130,000[2][4] |

| Brazil | 90,000–120,000[1][4] |

| South Africa | 51,000–75,000[2] |

| Hungary | 46,500–75,000[1] |

| Ukraine | 40,000–90,000[1] |

| Mexico | 40,000–45,000[1] |

| Netherlands | 29,700–43,000[1] |

| Belgium | 28,800–35,000[1] |

| Italy | 27,000–34,000[1] |

| Switzerland | 18,800–22,000[1] |

| Uruguay | 16,300–20,000[1] |

| Chile | 15,800–20,000[1] |

| Sweden | 14,900–20,000[1] |

| Turkey | 14,300–17,500[1] |

| Spain | 12,900–16,000[1] |

| Austria | 10,300–14,000[1] |

| Panama | 10,000–11,000[1] |

| Languages | |

| |

| Religion | |

Majority:

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

The Jews (Hebrew: יְהוּדִים, ISO 259-2: Yehudim, Israeli pronunciation: [jehuˈdim]) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group[14] and nation[15] originating from the Israelites of the historical kingdoms of Israel and Judah,[16] and whose traditional religion is Judaism.[17][18] Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly interrelated,[19][20] as Judaism is an ethnic religion,[21][22] but not all ethnic Jews practice Judaism.[23][24][25] Despite this, religious Jews regard individuals who have formally converted to Judaism as Jews.[23][26]

The Israelites emerged from within the Canaanite population to establish the Iron Age kingdoms of Israel and Judah.[27] Judaism emerged from the Israelite religion of Yahwism by the late 6th century BCE,[28] with a theology considered by religious Jews to be the expression of a covenant with God established with the Israelites, their ancestors.[29] The Babylonian captivity of Judahites following their kingdom's destruction,[30] the movement of Jewish groups around the Mediterranean in the Hellenistic period, and subsequent periods of conflict and violent dispersion, such as the Jewish–Roman wars, gave rise to the Jewish diaspora. The Jewish diaspora is a wide dispersion of Jewish communities across the world that have maintained their sense of Jewish history, identity and culture.[31]

In the following millennia, Jewish diaspora communities coalesced into three major ethnic subdivisions according to where their ancestors settled: the Ashkenazim (Central and Eastern Europe), the Sephardim (Iberian Peninsula), and the Mizrahim (Middle East and North Africa).[32][33] While these three major divisions account for most of the world's Jews, there are other smaller Jewish groups outside of the three.[34] Prior to World War II, the global Jewish population reached a peak of 16.7 million,[35] representing around 0.7% of the world's population at that time. During World War II, approximately 6 million Jews throughout Europe were systematically murdered by Nazi Germany in a genocide known as the Holocaust.[36][37] Since then, the population has slowly risen again, and as of 2021[update], was estimated to be at 15.2 million by the demographer Sergio Della Pergola[2] or less than 0.2% of the total world population in 2012.[38][b] Today, over 85% of Jews live in Israel or the United States. Israel, whose population is 73.9% Jewish, is the only country where Jews comprise more than 2.5% of the population.[2]

Jews have significantly influenced and contributed to the development and growth of human progress in many fields, both historically and in modern times, including in science and technology,[40] philosophy,[41] ethics,[42] literature,[40] governance,[40] business,[40] art, music, comedy, theatre,[43] cinema, architecture,[40] food, medicine,[44][45] and religion. Jews wrote the Bible,[46][47] founded Christianity,[48] and had an indirect but profound influence on Islam.[49] In these ways, Jews have also played a significant role in the development of Western culture.[50][51]

Name and etymology

The term "Jew" is derived from the Hebrew word יְהוּדִי Yehudi, with the plural יְהוּדִים Yehudim.[52] Endonyms in other Jewish languages include the Ladino ג׳ודיו Djudio (plural ג׳ודיוס, Djudios) and the Yiddish ייִד Yid (plural ייִדן Yidn). Originally, in ancient times, Yehudi (Jew)[53] was used to describe the inhabitants of the Israelite kingdom of Judah.[54] It is also used to distinguish their descendants from the gentiles and the Samaritans.[55] According to the Hebrew Bible, these inhabitants predominately descend from the tribe of Judah from Judah, the fourth son of Jacob.[56] Together the tribe of Judah and the tribe of Benjamin made up the Kingdom of Judah.[53]

Though Genesis 29:35 and 49:8 connect "Judah" with the verb yada, meaning "praise", scholars generally agree that "Judah" most likely derives from the name of a Levantine geographic region dominated by gorges and ravines.[57][58] In ancient times, Jewish people as a whole were called Hebrews or Israelites until the Babylonian Exile. After the Exile, the term Yehudi (Jew) was used for all followers of Judaism because the survivors of the Exile (who were the former residents of the Kingdom of Judah) were the only Israelites that had kept their distinct identity as the ten tribes from the northern Kingdom of Israel had been scattered and assimilated into other populations.[53] The gradual ethnonymic shift from "Israelites" to "Jews", regardless of their descent from Judah, although not contained in the Torah, is made explicit in the Book of Esther (4th century BCE) of the Tanakh.[59] Some modern scholars disagree with the conflation, based on the works of Josephus, Philo and Apostle Paul.[60]

The English word "Jew" is a derivation of Middle English Gyw, Iewe. The latter was loaned from the Old French giu, which itself evolved from the earlier juieu, which in turn derived from judieu/iudieu which through elision had dropped the letter "d" from the Medieval Latin Iudaeus, which, like the New Testament Greek term Ioudaios, meant both "Jew" and "Judean" / "of Judea".[61] The Greek term was a loan from Aramaic *yahūdāy, corresponding to Hebrew יְהוּדִי Yehudi.[56]

Some scholars prefer translating Ioudaios as "Judean" in the Bible since it is more precise, denotes the community's origins and prevents readers from engaging in antisemitic eisegesis.[62][63] Others disagree, believing that it erases the Jewish identity of Biblical characters such as Jesus.[55] Daniel R. Schwartz distinguishes "Judean" and "Jew". Here, "Judean" refers to the inhabitants of Judea, which encompassed southern Palestine. Meanwhile, "Jew" refers to the descendants of Israelites that adhere to Judaism. Converts are included in the definition.[64] But Shaye J.D. Cohen argues that "Judean" should include believers of the Judean God and allies of the Judean state.[65] Troy W. Martin similarly argues that biblical Jewishness is not dependent on ancestry but instead, is based on adherence to 'covenantal circumcision' (Genesis 17:9–14).[66]

The etymological equivalent is in use in other languages, e.g., يَهُودِيّ yahūdī (sg.), al-yahūd (pl.), in Arabic, "Jude" in German, "judeu" in Portuguese, "Juif" (m.)/"Juive" (f.) in French, "jøde" in Danish and Norwegian, "judío/a" in Spanish, "jood" in Dutch, "żyd" in Polish etc., but derivations of the word "Hebrew" are also in use to describe a Jew, e.g., in Italian (Ebreo), in Persian ("Ebri/Ebrani" (Persian: عبری/عبرانی)) and Russian (Еврей, Yevrey).[67] The German word "Jude" is pronounced [ˈjuːdə], the corresponding adjective "jüdisch" [ˈjyːdɪʃ] (Jewish) is the origin of the word "Yiddish".[68]

According to The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, fourth edition (2000),

It is widely recognized that the attributive use of the noun Jew, in phrases such as Jew lawyer or Jew ethics, is both vulgar and highly offensive. In such contexts Jewish is the only acceptable possibility. Some people, however, have become so wary of this construction that they have extended the stigma to any use of Jew as a noun, a practice that carries risks of its own. In a sentence such as There are now several Jews on the council, which is unobjectionable, the substitution of a circumlocution like Jewish people or persons of Jewish background may in itself cause offense for seeming to imply that Jew has a negative connotation when used as a noun.[69]

Identity

Judaism shares some of the characteristics of a nation,[70][71][72][73][74][75] an ethnicity,[14] a religion, and a culture,[76][77][78] making the definition of who is a Jew vary slightly depending on whether a religious or national approach to identity is used.[79][better source needed] Generally, in modern secular usage, Jews include three groups: people who were born to a Jewish family regardless of whether or not they follow the religion, those who have some Jewish ancestral background or lineage (sometimes including those who do not have strictly matrilineal descent), and people without any Jewish ancestral background or lineage who have formally converted to Judaism and therefore are followers of the religion.[80]

Historical definitions of Jewish identity have traditionally been based on halakhic definitions of matrilineal descent, and halakhic conversions. These definitions of who is a Jew date back to the codification of the Oral Torah into the Babylonian Talmud, around 200 CE. Interpretations by Jewish sages of sections of the Tanakh – such as Deuteronomy 7:1–5, which forbade intermarriage between their Israelite ancestors and seven non-Israelite nations: "for that [i.e. giving your daughters to their sons or taking their daughters for your sons,] would turn away your children from following me, to serve other gods" [27][failed verification] – are used as a warning against intermarriage between Jews and gentiles. Leviticus 24:10 says that the son in a marriage between a Hebrew woman and an Egyptian man is "of the community of Israel." This is complemented by Ezra 10:2–3, where Israelites returning from Babylon vow to put aside their gentile wives and their children.[81][82] A popular theory is that the rape of Jewish women in captivity brought about the law of Jewish identity being inherited through the maternal line, although scholars challenge this theory citing the Talmudic establishment of the law from the pre-exile period.[83] Another argument is that the rabbis changed the law of patrilineal descent to matrilineal descent due to the widespread rape of Jewish women by Roman soldiers.[84] Since the anti-religious Haskalah movement of the late 18th and 19th centuries, halakhic interpretations of Jewish identity have been challenged.[85]

According to historian Shaye J. D. Cohen, the status of the offspring of mixed marriages was determined patrilineally in the Bible. He brings two likely explanations for the change in Mishnaic times: first, the Mishnah may have been applying the same logic to mixed marriages as it had applied to other mixtures (Kil'ayim). Thus, a mixed marriage is forbidden as is the union of a horse and a donkey, and in both unions the offspring are judged matrilineally.[86] Second, the Tannaim may have been influenced by Roman law, which dictated that when a parent could not contract a legal marriage, offspring would follow the mother.[86] Rabbi Rivon Krygier follows a similar reasoning, arguing that Jewish descent had formerly passed through the patrilineal descent and the law of matrilineal descent had its roots in the Roman legal system.[83]

Origins

The prehistory and ethnogenesis of the Jews are closely intertwined with archaeology, biology, historical textual records, mythology, and religious literature. The ethnic stock to which Jews originally trace their ancestry was a confederation of Iron Age Semitic-speaking tribes known as the Israelites that inhabited a part of Canaan during the tribal and monarchic periods.[93] Modern Jews are named after and also descended from the southern Israelite Kingdom of Judah.[94][95][96][97][98][99] Gary A. Rendsburg links the early Canaanite nomadic pastoralists confederation to the Shasu known to the Egyptians around the 15th century BCE.[100]

According to the Hebrew Bible narrative, Jewish ancestry is traced back to the Biblical patriarchs such as Abraham, his son Isaac, Isaac's son Jacob, and the Biblical matriarchs Sarah, Rebecca, Leah, and Rachel, who lived in Canaan. The Twelve Tribes are described as descending from the twelve sons of Jacob. Jacob and his family migrated to Ancient Egypt after being invited to live with Jacob's son Joseph by the Pharaoh himself. The patriarchs' descendants were later enslaved until the Exodus led by Moses, after which the Israelites conquered Canaan under Moses' successor Joshua, went through the period of the Biblical judges after the death of Joshua, then through the mediation of Samuel became subject to a king, Saul, who was succeeded by David and then Solomon, after whom the United Monarchy ended and was split into a separate Kingdom of Israel and a Kingdom of Judah. The Kingdom of Judah is described as comprising the tribes of Judah, Benjamin, partially Levi, and later adding remnants of other tribes who migrated there from the northern Kingdom of Israel.[101][102][103]

In the extra-biblical record, the Israelites become visible as a people between 1200 and 1000 BCE.[104] There is well accepted archeological evidence referring to "Israel" in the Merneptah Stele, which dates to about 1200 BCE,[105][106] and in the Mesha stele from 840 BCE. It is debated whether a period like that of the Biblical judges occurred[107][108][109][110][111] and if there ever was a United Monarchy.[112][113][114][115] There is further disagreement about the earliest existence of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah and their extent and power. Historians agree that a Kingdom of Israel existed by c. 900 BCE,[113]: 169–95 [114][115] there is a consensus that a Kingdom of Judah existed by c. 700 BCE at least,[116] and recent excavations in Khirbet Qeiyafa have provided strong evidence for dating the Kingdom of Judah to the 10th century BCE.[117] In 587 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar II, King of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, besieged Jerusalem, destroyed the First Temple and deported parts of the Judahite population.[118]

Scholars disagree regarding the extent to which the Bible should be accepted as a historical source for early Israelite history. Rendsburg states that there are two approximately equal groups of scholars who debate the historicity of the biblical narrative, the minimalists who largely reject it, and the maximalists who largely accept it, with the minimalists being the more vocal of the two.[119]

Some of the leading minimalists reframe the biblical account as constituting the Israelites' inspiring national myth narrative, suggesting that according to the modern archaeological and historical account, the Israelites and their culture did not overtake the region by force, but instead branched out of the Canaanite peoples and culture through the development of a distinct monolatristic—and later monotheistic—religion of Yahwism centered on Yahweh, one of the gods of the Canaanite pantheon. The growth of Yahweh-centric belief, along with a number of cultic practices, gradually gave rise to a distinct Israelite ethnic group, setting them apart from other Canaanites.[120][121][122] According to Dever, modern archaeologists have largely discarded the search for evidence of the biblical narrative surrounding the patriarchs and the exodus.[123]

According to the maximalist position, the modern archaeological record independently points to a narrative which largely agrees with the biblical account. This narrative provides a testimony of the Israelites as a nomadic people known to the Egyptians as belonging to the Shasu. Over time these nomads left the desert and settled on the central mountain range of the land of Canaan, in simple semi-nomadic settlements in which pig bones are notably absent. This population gradually shifted from a tribal lifestyle to a monarchy. While the archaeological record of the ninth century BCE provides evidence for two monarchies, one in the south under a dynasty founded by a figure named David with its capital in Jerusalem, and one in the north under a dynasty founded by a figure named Omri with its capital in Samaria. It also points to an early monarchic period in which these regions shared material culture and religion, suggesting a common origin. Archaeological finds also provide evidence for the later cooperation of these two kingdoms in their coalition against Aram, and for their destructions by the Assyrians and later by the Babylonians.[124]

Genetic studies on Jews show that most Jews worldwide bear a common genetic heritage which originates in the Middle East, and that they share certain genetic traits with other Gentile peoples of the Fertile Crescent.[125][126][127] The genetic composition of different Jewish groups shows that Jews share a common gene pool dating back four millennia, as a marker of their common ancestral origin.[128] Despite their long-term separation, Jewish communities maintained their unique commonalities, propensities, and sensibilities in culture, tradition, and language.[129]

History

| Tribes of Israel |

|---|

|

Israel and Judah

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele, which dates to around 1200 BCE. The majority of scholars agree that this text refers to the Israelites, a group that inhabited the central highlands of Canaan, where archaeological evidence shows that hundreds of small settlements were constructed between the 12th and 10th centuries BCE.[130][131] The Israelites differentiated themselves from neighboring peoples through various distinct characteristics including religious practices, prohibition on intermarriage, and an emphasis on genealogy and family history.[132][133][133]

In the 10th century BCE, two neighboring Israelite kingdoms—the northern Kingdom of Israel and the southern Kingdom of Judah—emerged. Since their inception, they shared ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious characteristics despite a complicated relationship. Israel, with its capital mostly in Samaria, was larger and wealthier, and soon developed into a regional power.[134] In contrast, Judah, with its capital in Jerusalem, was less prosperous and covered a smaller, mostly mountainous territory. However, while in Israel the royal succession was often decided by a military coup d'état, resulting in several dynasty changes, political stability in Judah was much greater, as it was ruled by the House of David for the whole four centuries of its existence.[135]

Around 720 BCE, Kingdom of Israel was destroyed when it was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which came to dominate the ancient Near East.[101] Under the Assyrian resettlement policy, a significant portion of the northern Israelite population was exiled to Mesopotamia and replaced by immigrants from the same region.[136] During the same period, and throughout the 7th century BCE, the Kingdom of Judah, now under Assyrian vassalage, experienced a period of prosperity and witnessed a significant population growth.[137] This prosperity continued until the Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib devastated the region of Judah in response to a rebellion in the area, ultimately halting at Jerusalem.[138] Later in the same century, the Assyrians were defeated by the rising Neo-Babylonian Empire, and Judah became its vassal. In 587 BCE, following a revolt in Judah, the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II besieged and destroyed Jerusalem and the First Temple, putting an end to the kingdom. The majority of Jerusalem's residents, including the kingdom's elite, were exiled to Babylon.[139][140]

Second Temple period

According to the Book of Ezra, the Persian Cyrus the Great ended the Babylonian exile in 538 BCE,[141] the year after he captured Babylon.[142] The exile ended with the return under Zerubbabel the Prince (so called because he was a descendant of the royal line of David) and Joshua the Priest (a descendant of the line of the former High Priests of the Temple) and their construction of the Second Temple circa 521–516 BCE.[141] As part of the Persian Empire, the former Kingdom of Judah became the province of Judah (Yehud Medinata),[143] with a smaller territory[144] and a reduced population.[113]

Judea was under control of the Achaemenids until the fall of their empire in c. 333 BCE to Alexander the Great. After several centuries under foreign imperial rule, the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire resulted in an independent Hasmonean kingdom, under which the Jews once again enjoyed political independence for a period spanning from 110 to 63 BCE.[145] Under Hasmonean rule the boundaries of their kingdom were expanded to include not only the land of the historical kingdom of Judah, but also the Galilee and Transjordan.[146] In the beginning of this process the Idumeans, who had infiltrated southern Judea after the destruction of the First Temple, were converted en masse.[147][148] In 63 BCE, Judea was conquered by the Romans. From 37 BCE to 6 CE, the Romans allowed the Jews to maintain some degree of independence by installing the Herodian dynasty as vassal kings. However, Judea eventually came directly under Roman control and was incorporated into the Roman Empire as the province of Judaea.[149][150]

The Jewish–Roman wars, a series of unsuccessful revolts against Roman rule during the first and second centuries CE, had significant and disastrous consequences for the Jewish population of Judaea.[151][152] The First Jewish-Roman War (66–73 CE) culminated in the destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple. The severely reduced Jewish population of Judaea was denied any kind of political self-government.[153] A few generations later, the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 CE) erupted, and its brutal suppression by the Romans led to the depopulation of Judea. Following the revolt, Jews were forbidden from residing in the vicinity of Jerusalem, and the Jewish demographic center in Judaea shifted to Galilee.[154][155][156] Similar upheavals impacted the Jewish communities in the empire's eastern provinces during the Diaspora Revolt (115–117 CE), leading to the near-total destruction of Jewish diaspora communities in Libya, Cyprus and Egypt,[157][158] including the highly influential community in Alexandria.[153][157]

The destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE brought profound changes to Judaism. With the Temple's central place in Jewish worship gone, religious practices shifted towards prayer, Torah study (including Oral Torah), and communal gatherings in synagogues. Judaism also lost much of its sectarian nature.[159]: 69 Two of the three main sects that flourished during the late Second Temple period, namely the Sadducees and Essenes, eventually disappeared, while Pharisaic beliefs became the foundational, liturgical, and ritualistic basis of Rabbinic Judaism, which emerged as the prevailing form of Judaism since late antiquity.[160]

Babylon and Rome

The Jewish diaspora existed well before the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE and had been ongoing for centuries, with the dispersal driven by both forced expulsions and voluntary migrations.[161][153] In Mesopotamia, a testimony to the beginnings of the Jewish community can be found in Joachin's ration tablets, listing provisions allotted to the exiled Judean king and his family by Nebuchadnezzar II, and further evidence are the Al-Yahudu tablets, dated to the 6th–5th centuries BCE and related to the exiles from Judea arriving after the destruction of the First Temple,[118] though there is ample evidence for the presence of Jews in Babylonia even from 626 BCE.[162] In Egypt, the documents from Elephantine reveal the trials of a community founded by a Persian Jewish garrison at two fortresses on the frontier during the 5th–4th centuries BCE, and according to Josephus the Jewish community in Alexandria existed since the founding of the city in the 4th century BCE by Alexander the Great.[163] By 200 BCE, there were well established Jewish communities both in Egypt and Mesopotamia ("Babylonia" in Jewish sources) and in the two centuries that followed, Jewish populations were also present in Asia Minor, Greece, Macedonia, Cyrene, and, beginning in the middle of the first century BCE, in the city of Rome.[164][153] Later, in the first centuries CE, as a result of the Jewish-Roman Wars, a large number of Jews were taken as captives, sold into slavery, or compelled to flee from the regions affected by the wars, contributing to the formation and expansion of Jewish communities across the Roman Empire as well as in Arabia and Mesopotamia.

After the Bar Kokhba revolt, the Jewish population in Judaea, now significantly reduced in size, made efforts to recover from the revolt's devastating effects, but never fully regained its previous strength.[165][166] In the second to fourth centuries CE, the region of Galilee emerged as the new center of Jewish life in Syria Palaestina, experiencing a cultural and demographic flourishing. It was in this period that two central rabbinic texts, the Mishnah and the Jerusalem Talmud, were composed.[167] However, as the Roman Empire was replaced by the Christianized Byzantine Empire under Constantine, Jews came to be persecuted by the church and the authorities, and many immigrated to communities in the diaspora. In the fourth century CE, Jews are believed to have lost their position as the majority in Syria Palaestina.[168][165]

The long-established Jewish community of Mesopotamia, which had been living under Parthian and later Sasanian rule, beyond the confines of the Roman Empire, became an important center of Jewish study as Judea's Jewish population declined.[168][165] Estimates often place the Babylonian Jewish community of the 3rd to 7th centuries at around one million, making it the largest Jewish diaspora community of that period.[169] Under the political leadership of the exilarch, who was regarded as a royal heir of the House of David, this community had an autonomous status and served as a place of refuge for the Jews of Syria Palaestina. A number of significant Talmudic academies, such as the Nehardea, Pumbedita, and Sura academies, were established in Mesopotamia, and many important Amoraim were active there. The Babylonian Talmud, a centerpiece of Jewish religious law, was compiled in Babylonia in the 3rd to 6th centuries.[170]

Middle Ages

Jewish diaspora communities are generally described to have coalesced into three major ethnic subdivisions according to where their ancestors settled: the Ashkenazim (initially in the Rhineland and France), the Sephardim (initially in the Iberian Peninsula), and the Mizrahim (Middle East and North Africa).[171] Romaniote Jews, Tunisian Jews, Yemenite Jews, Egyptian Jews, Ethiopian Jews, Bukharan Jews, Mountain Jews, and other groups also predated the arrival of the Sephardic diaspora.[172]

Despite experiencing repeated waves of persecution, Ashkenazi Jews in Western Europe worked in a variety of fields, making an impact on their communities' economy and societies. In Francia, for example, figures like Isaac Judaeus and Armentarius occupied prominent social and economic positions. However, Jews were frequently the subjects of discriminatory laws, segregation, blood libels and pogroms, which culminated in events like the Rhineland Massacres (1066) and the expulsion of Jews from England (1290). As a result, Ashkenazi Jews were gradually pushed eastwards to Poland, Lithuania and Russia.[173]

During the same period, Jewish communities in the Middle East thrived under Islamic rule, especially in cities like Baghdad, Cairo, and Damascus. In Babylonia, from the 7th to 11th centuries the Pumbedita and Sura academies led the Arab and to an extant the entire Jewish world. The deans and students of said academies defined the Geonic period in Jewish history.[174] Following this period were the Rishonim who lived from the 11th to 15th centuries. Like their European counterparts, Jews in the Middle East and North Africa also faced periods of persecution and discriminatory policies, with the Almohad Caliphate in North Africa and Iberia issuing forced conversion decrees, causing Jews such as Maimonides to seek safety in other regions.

Initially, under Visigoth rule, Jews in the Iberian Peninsula faced persecutions, but their circumstances changed dramatically under Islamic rule. During this period, they thrived in a golden age, marked by significant intellectual and cultural contributions in fields such as philosophy, medicine, and literature by figures such as Samuel ibn Naghrillah, Judah Halevi and Solomon ibn Gabirol. However, in the 12th to 15th centuries, the Iberian Peninsula witnessed a rise in antisemitism, leading to persecutions, anti-Jewish laws, massacres and forced conversions (peaking in 1391), and the establishment of the Spanish Inquisition that same year. After the completion of the Reconquista and the issuance of the Alhambra Decree by the Catholic Monarchs in 1492, the Jews of Spain were forced to choose: convert to Christianity or be expelled. As a result, around 200,000 Jews were expelled from Spain, seeking refuge in places such as the Ottoman Empire, North Africa, Italy, the Netherlands and India. A similar fate awaited the Jews of Portugal a few years later. Some Jews chose to remain, and pretended to practice Catholicism. These Jews would form the members of Crypto-Judaism.[175]

Modern period

In the 19th century, when Jews in Western Europe were increasingly granted equality before the law, Jews in the Pale of Settlement faced growing persecution, legal restrictions and widespread pogroms. Zionism emerged in the late 19th century in Central and Eastern Europe as a national revival movement, aiming to re-establish a Jewish polity in the Land of Israel, an endeavor to restore the Jewish people back to their ancestral homeland in order to stop the exoduses and persecutions that have plagued their history. This led to waves of Jewish migration to Ottoman-controlled Palestine. Theodor Herzl, who is considered the father of political Zionism,[176] offered his vision of a future Jewish state in his 1896 book Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State); a year later, he presided over the First Zionist Congress.[177]

The antisemitism that inflicted Jewish communities in Europe also triggered a mass exodus of more than two million Jews to the United States between 1881 and 1924.[178] The Jews of Europe and the United States gained success in the fields of science, culture and the economy. Among those generally considered the most famous were Albert Einstein and Ludwig Wittgenstein. Many Nobel Prize winners at this time were Jewish, as is still the case.[179]

When Adolf Hitler and the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, the situation for Jews deteriorated rapidly. Many Jews fled from Europe to Mandatory Palestine, the United States, and the Soviet Union as a result of racial anti-Semitic laws, economic difficulties, and the fear of an impending war. World War II started in 1939, and by 1941, Hitler occupied almost all of Europe. Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, the Final Solution—an extensive, organized effort with an unprecedented scope intended to annihilate the Jewish people—began, and resulted in the persecution and murder of Jews in Europe and North Africa. In Poland, three million were murdered in gas chambers in all concentration camps combined, with one million at the Auschwitz camp complex alone. The Holocaust is the name given to this genocide, in which six million Jews were systematically murdered.

Before and during the Holocaust, enormous numbers of Jews immigrated to Mandatory Palestine. On 14 May 1948, upon the termination of the mandate, David Ben-Gurion declared the creation of the State of Israel, a Jewish and democratic state in the Land of Israel. Immediately afterwards, all neighboring Arab states invaded, yet the newly formed IDF resisted. In 1949, the war ended and Israel started building the state and absorbing massive waves of Aliyah from all over the world.

Culture

Religion

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

The Jewish people and the religion of Judaism are strongly interrelated. Converts to Judaism typically have a status within the Jewish ethnos equal to those born into it.[180] However, several converts to Judaism, as well as ex-Jews, have claimed that converts are treated as second-class Jews by many born Jews.[181] Conversion is not encouraged by mainstream Judaism, and it is considered a difficult task. A significant portion of conversions are undertaken by children of mixed marriages, or would-be or current spouses of Jews.[182]

The Hebrew Bible, a religious interpretation of the traditions and early history of the Jews, established the first of the Abrahamic religions, which are now practiced by 54 percent of the world. Judaism guides its adherents in both practice and belief, and has been called not only a religion, but also a "way of life,"[183] which has made drawing a clear distinction between Judaism, Jewish culture, and Jewish identity rather difficult. Throughout history, in eras and places as diverse as the ancient Hellenic world,[184] in Europe before and after The Age of Enlightenment (see Haskalah),[185] in Islamic Spain and Portugal,[186] in North Africa and the Middle East,[186] India,[187] China,[188] or the contemporary United States[189] and Israel,[190] cultural phenomena have developed that are in some sense characteristically Jewish without being at all specifically religious. Some factors in this come from within Judaism, others from the interaction of Jews or specific communities of Jews with their surroundings, and still others from the inner social and cultural dynamics of the community, as opposed to from the religion itself. This phenomenon has led to considerably different Jewish cultures unique to their own communities.[191]

Languages

Hebrew is the liturgical language of Judaism (termed lashon ha-kodesh, "the holy tongue"), the language in which most of the Hebrew scriptures (Tanakh) were composed, and the daily speech of the Jewish people for centuries. By the 5th century BCE, Aramaic, a closely related tongue, joined Hebrew as the spoken language in Judea.[192] By the 3rd century BCE, some Jews of the diaspora were speaking Greek.[193] Others, such as in the Jewish communities of Asoristan, known to Jews as Babylonia, were speaking Hebrew and Aramaic, the languages of the Babylonian Talmud. Dialects of these same languages were also used by the Jews of Syria Palaestina at that time.[citation needed]

For centuries, Jews worldwide have spoken the local or dominant languages of the regions they migrated to, often developing distinctive dialectal forms or branches that became independent languages. Yiddish is the Judaeo-German language developed by Ashkenazi Jews who migrated to Central Europe. Ladino is the Judaeo-Spanish language developed by Sephardic Jews who migrated to the Iberian peninsula. Due to many factors, including the impact of the Holocaust on European Jewry, the Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries, and widespread emigration from other Jewish communities around the world, ancient and distinct Jewish languages of several communities, including Judaeo-Georgian, Judaeo-Arabic, Judaeo-Berber, Krymchak, Judaeo-Malayalam and many others, have largely fallen out of use.[5]

For over sixteen centuries Hebrew was used almost exclusively as a liturgical language, and as the language in which most books had been written on Judaism, with a few speaking only Hebrew on the Sabbath.[194] Hebrew was revived as a spoken language by Eliezer ben Yehuda, who arrived in Palestine in 1881. It had not been used as a mother tongue since Tannaic times.[192] Modern Hebrew is designated as the "State language" of Israel.[195]

Despite efforts to revive Hebrew as the national language of the Jewish people, knowledge of the language is not commonly possessed by Jews worldwide and English has emerged as the lingua franca of the Jewish diaspora.[196][197][198][199][200] Although many Jews once had sufficient knowledge of Hebrew to study the classic literature, and Jewish languages like Yiddish and Ladino were commonly used as recently as the early 20th century, most Jews lack such knowledge today and English has by and large superseded most Jewish vernaculars. The three most commonly spoken languages among Jews today are Hebrew, English, and Russian. Some Romance languages, particularly French and Spanish, are also widely used.[5] Yiddish has been spoken by more Jews in history than any other language,[201] but it is far less used today following the Holocaust and the adoption of Modern Hebrew by the Zionist movement and the State of Israel. In some places, the mother language of the Jewish community differs from that of the general population or the dominant group. For example, in Quebec, the Ashkenazic majority has adopted English, while the Sephardic minority uses French as its primary language.[202][203][204] Similarly, South African Jews adopted English rather than Afrikaans.[205] Due to both Czarist and Soviet policies,[206][207] Russian has superseded Yiddish as the language of Russian Jews, but these policies have also affected neighboring communities.[208] Today, Russian is the first language for many Jewish communities in a number of Post-Soviet states, such as Ukraine[209][210][211][212] and Uzbekistan,[213][better source needed] as well as for Ashkenazic Jews in Azerbaijan,[214][215] Georgia,[216] and Tajikistan.[217][218] Although communities in North Africa today are small and dwindling, Jews there had shifted from a multilingual group to a monolingual one (or nearly so), speaking French in Algeria,[219] Morocco,[214] and the city of Tunis,[220][221] while most North Africans continue to use Arabic or Berber as their mother tongue.[citation needed]

Leadership

There is no single governing body for the Jewish community, nor a single authority with responsibility for religious doctrine.[222] Instead, a variety of secular and religious institutions at the local, national, and international levels lead various parts of the Jewish community on a variety of issues.[223] Today, many countries have a Chief Rabbi who serves as a representative of that country's Jewry. Although many Hasidic Jews follow a certain hereditary Hasidic dynasty, there is no one commonly accepted leader of all Hasidic Jews. Many Jews believe that the Messiah will act a unifying leader for Jews and the entire world.[224]

Theories on ancient Jewish national identity

A number of modern scholars of nationalism support the existence of Jewish national identity in antiquity. One of them is David Goodblatt,[225] who generally believes in the existence of nationalism before the modern period. In his view, the Bible, the parabiblical literature and the Jewish national history provide the base for a Jewish collective identity. Although many of the ancient Jews were illiterate (as were their neighbors), their national narrative was reinforced through public readings. The Hebrew language also constructed and preserved national identity. Although it was not widely spoken after the 5th century BCE, Goodblatt states:[226][227][228]

the mere presence of the language in spoken or written form could invoke the concept of a Jewish national identity. Even if one knew no Hebrew or was illiterate, one could recognize that a group of signs was in Hebrew script. ... It was the language of the Israelite ancestors, the national literature, and the national religion. As such it was inseparable from the national identity. Indeed its mere presence in visual or aural medium could invoke that identity.

Anthony D. Smith, an historical sociologist considered one of the founders of the field of nationalism studies, wrote that the Jews of the late Second Temple period provide "a closer approximation to the ideal type of the nation [...] than perhaps anywhere else in the ancient world." He adds that this observation "must make us wary of pronouncing too readily against the possibility of the nation, and even a form of religious nationalism, before the onset of modernity."[229] Agreeing with Smith, Goodblatt suggests omitting the qualifier "religious" from Smith's definition of ancient Jewish nationalism, noting that, according to Smith, a religious component in national memories and culture is common even in the modern era.[230] This view is echoed by political scientist Tom Garvin, who writes that "something strangely like modern nationalism is documented for many peoples in medieval times and in classical times as well," citing the ancient Jews as one of several "obvious examples", alongside the classical Greeks and the Gaulish and British Celts.[231]

Fergus Millar suggests that the sources of Jewish national identity and their early nationalist movements in the first and second centuries CE included several key elements: the Bible as both a national history and legal source, the Hebrew language as a national language, a system of law, and social institutions such as schools, synagogues, and Sabbath worship.[232] Adrian Hastings argued that Jews are the "true proto-nation", that through the model of ancient Israel found in the Hebrew Bible, provided the world with the original concept of nationhood which later influenced Christian nations. However, following Jerusalem's destruction in the first century CE, Jews ceased to be a political entity and did not resemble a traditional nation-state for almost two millennia. Despite this, they maintained their national identity through collective memory, religion and sacred texts, even without land or political power, and remained a nation rather than just an ethnic group, eventually leading to the rise of Zionism and the establishment of Israel.[233]

It is believed that Jewish nationalist sentiment in antiquity was encouraged because under foreign rule (Persians, Greeks, Romans) Jews were able to claim that they were an ancient nation. This claim was based on the preservation and reverence of their scriptures, the Hebrew language, the Temple and priesthood, and other traditions of their ancestors.[234]

Demographics

Ethnic divisions

Within the world's Jewish population there are distinct ethnic divisions, most of which are primarily the result of geographic branching from an originating Israelite population, and subsequent independent evolutions. An array of Jewish communities was established by Jewish settlers in various places around the Old World, often at great distances from one another, resulting in effective and often long-term isolation. During the millennia of the Jewish diaspora the communities would develop under the influence of their local environments: political, cultural, natural, and populational. Today, manifestations of these differences among the Jews can be observed in Jewish cultural expressions of each community, including Jewish linguistic diversity, culinary preferences, liturgical practices, religious interpretations, as well as degrees and sources of genetic admixture.[235]

Jews are often identified as belonging to one of two major groups: the Ashkenazim and the Sephardim. Ashkenazim are so named in reference to their geographical origins (their ancestors' culture coalesced in the Rhineland, an area historically referred to by Jews as Ashkenaz). Similarly, Sephardim (Sefarad meaning "Spain" in Hebrew) are named in reference their origins in Iberia. The diverse groups of Jews of the Middle East and North Africa are often collectively referred to as Sephardim together with Sephardim proper for liturgical reasons having to do with their prayer rites. A common term for many of these non-Spanish Jews who are sometimes still broadly grouped as Sephardim is Mizrahim (lit. "easterners" in Hebrew). Nevertheless, Mizrahis and Sepharadim are usually ethnically distinct.[236]

Smaller groups include, but are not restricted to, Indian Jews such as the Bene Israel, Bnei Menashe, Cochin Jews, and Bene Ephraim; the Romaniotes of Greece; the Italian Jews ("Italkim" or "Bené Roma"); the Teimanim from Yemen; various African Jews, including most numerously the Beta Israel of Ethiopia; and Chinese Jews, most notably the Kaifeng Jews, as well as various other distinct but now almost extinct communities.[237]

The divisions between all these groups are approximate and their boundaries are not always clear. The Mizrahim for example, are a heterogeneous collection of North African, Central Asian, Caucasian, and Middle Eastern Jewish communities that are no closer related to each other than they are to any of the earlier mentioned Jewish groups. In modern usage, however, the Mizrahim are sometimes termed Sephardi due to similar styles of liturgy, despite independent development from Sephardim proper. Thus, among Mizrahim there are Egyptian Jews, Iraqi Jews, Lebanese Jews, Kurdish Jews, Moroccan Jews, Libyan Jews, Syrian Jews, Bukharian Jews, Mountain Jews, Georgian Jews, Iranian Jews, Afghan Jews, and various others. The Teimanim from Yemen are sometimes included, although their style of liturgy is unique and they differ in respect to the admixture found among them to that found in Mizrahim. In addition, there is a differentiation made between Sephardi migrants who established themselves in the Middle East and North Africa after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain and Portugal in the 1490s and the pre-existing Jewish communities in those regions.[237]

Ashkenazi Jews represent the bulk of modern Jewry, with at least 70 percent of Jews worldwide (and up to 90 percent prior to World War II and the Holocaust). As a result of their emigration from Europe, Ashkenazim also represent the overwhelming majority of Jews in the New World continents, in countries such as the United States, Canada, Argentina, Australia, and Brazil. In France, the immigration of Jews from Algeria (Sephardim) has led them to outnumber the Ashkenazim.[237] Only in Israel is the Jewish population representative of all groups, a melting pot independent of each group's proportion within the overall world Jewish population.[238]

Genetic studies

Y DNA studies tend to imply a small number of founders in an old population whose members parted and followed different migration paths.[239] In most Jewish populations, these male line ancestors appear to have been mainly Middle Eastern. For example, Ashkenazi Jews share more common paternal lineages with other Jewish and Middle Eastern groups than with non-Jewish populations in areas where Jews lived in Eastern Europe, Germany, and the French Rhine Valley. This is consistent with Jewish traditions in placing most Jewish paternal origins in the region of the Middle East.[240][241]

Conversely, the maternal lineages of Jewish populations, studied by looking at mitochondrial DNA, are generally more heterogeneous.[242] Scholars such as Harry Ostrer and Raphael Falk believe this indicates that many Jewish males found new mates from European and other communities in the places where they migrated in the diaspora after fleeing ancient Israel.[243] In contrast, Behar has found evidence that about 40 percent of Ashkenazi Jews originate maternally from just four female founders, who were of Middle Eastern origin. The populations of Sephardi and Mizrahi Jewish communities "showed no evidence for a narrow founder effect."[242] Subsequent studies carried out by Feder et al. confirmed the large portion of non-local maternal origin among Ashkenazi Jews. Reflecting on their findings related to the maternal origin of Ashkenazi Jews, the authors conclude "Clearly, the differences between Jews and non-Jews are far larger than those observed among the Jewish communities. Hence, differences between the Jewish communities can be overlooked when non-Jews are included in the comparisons."[13][244][245] A study showed that 7% of Ashkenazi Jews have the haplogroup G2c, which is mainly found in Pashtuns and on lower scales all major Jewish groups, Palestinians, Syrians, and Lebanese.[246][247]

Studies of autosomal DNA, which look at the entire DNA mixture, have become increasingly important as the technology develops. They show that Jewish populations have tended to form relatively closely related groups in independent communities, with most in a community sharing significant ancestry in common.[248] For Jewish populations of the diaspora, the genetic composition of Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and Mizrahi Jewish populations show a predominant amount of shared Middle Eastern ancestry. According to Behar, the most parsimonious explanation for this shared Middle Eastern ancestry is that it is "consistent with the historical formulation of the Jewish people as descending from ancient Hebrew and Israelite residents of the Levant" and "the dispersion of the people of ancient Israel throughout the Old World".[249] North African, Italian and others of Iberian origin show variable frequencies of admixture with non-Jewish historical host populations among the maternal lines. In the case of Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews (in particular Moroccan Jews), who are closely related, the source of non-Jewish admixture is mainly Southern European, while Mizrahi Jews show evidence of admixture with other Middle Eastern populations. Behar et al. have remarked on a close relationship between Ashkenazi Jews and modern Italians.[249][250] A 2001 study found that Jews were more closely related to groups of the Fertile Crescent (Kurds, Turks, and Armenians) than to their Arab neighbors, whose genetic signature was found in geographic patterns reflective of Islamic conquests.[240][251]

The studies also show that Sephardic Bnei Anusim (descendants of the "anusim" who were forced to convert to Catholicism), which comprise up to 19.8 percent of the population of today's Iberia (Spain and Portugal) and at least 10 percent of the population of Ibero-America (Hispanic America and Brazil), have Sephardic Jewish ancestry within the last few centuries. The Bene Israel and Cochin Jews of India, Beta Israel of Ethiopia, and a portion of the Lemba people of Southern Africa, despite more closely resembling the local populations of their native countries, have also been thought to have some more remote ancient Jewish ancestry.[252][249][253][245] Views on the Lemba have changed and genetic Y-DNA analyses in the 2000s have established a partially Middle-Eastern origin for a portion of the male Lemba population but have been unable to narrow this down further.[254][255]

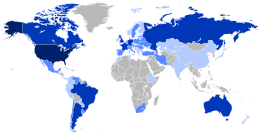

Population centers

Although historically, Jews have been found all over the world, in the decades since World War II and the establishment of Israel, they have increasingly concentrated in a small number of countries.[256][257] In 2021, Israel and the United States together accounted for over 85 percent of the global Jewish population, with approximately 45.3% and 39.6% of the world's Jews, respectively.[2] More than half (51.2%) of world Jewry resides in just ten metropolitan areas. As of 2021, these ten areas were Tel Aviv, New York, Jerusalem, Haifa, Los Angeles, Miami, Philadelphia, Paris, Washington, and Chicago. The Tel Aviv metro area has the highest percent of Jews among the total population (94.8%), followed by Jerusalem (72.3%), Haifa (73.1%), and Beersheba (60.4%), the balance mostly being Israeli Arabs. Outside Israel, the highest percent of Jews in a metropolitan area was in New York (10.8%), followed by Miami (8.7%), Philadelphia (6.8%), San Francisco (5.1%), Washington (4.7%), Los Angeles (4.7%), Toronto (4.5%), and Baltimore (4.1%).[2]

As of 2010, there were nearly 14 million Jews around the world, roughly 0.2% of the world's population at the time.[258] According to the 2007 estimates of The Jewish People Policy Planning Institute, the world's Jewish population is 13.2 million.[259] This statistic incorporates both practicing Jews affiliated with synagogues and the Jewish community, and approximately 4.5 million unaffiliated and secular Jews.[citation needed]

According to Sergio Della Pergola, a demographer of the Jewish population, in 2021 there were about 6.8 million Jews in Israel, 6 million in the United States, and 2.3 million in the rest of the world.[2]

Israel

Israel, the Jewish nation-state, is the only country in which Jews make up a majority of the citizens.[260] Israel was established as an independent democratic and Jewish state on 14 May 1948.[261] Of the 120 members in its parliament, the Knesset,[262] as of 2016[update], 14 members of the Knesset are Arab citizens of Israel (not including the Druze), most representing Arab political parties. One of Israel's Supreme Court judges is also an Arab citizen of Israel.[263]

Between 1948 and 1958, the Jewish population rose from 800,000 to two million.[264] Currently, Jews account for 75.4 percent of the Israeli population, or 6 million people.[265][266] The early years of the State of Israel were marked by the mass immigration of Holocaust survivors in the aftermath of the Holocaust and Jews fleeing Arab lands.[267] Israel also has a large population of Ethiopian Jews, many of whom were airlifted to Israel in the late 1980s and early 1990s.[268][269] Between 1974 and 1979 nearly 227,258 immigrants arrived in Israel, about half being from the Soviet Union.[270] This period also saw an increase in immigration to Israel from Western Europe, Latin America, and North America.[271]

A trickle of immigrants from other communities has also arrived, including Indian Jews and others, as well as some descendants of Ashkenazi Holocaust survivors who had settled in countries such as the United States, Argentina, Australia, Chile, and South Africa. Some Jews have emigrated from Israel elsewhere, because of economic problems or disillusionment with political conditions and the continuing Arab–Israeli conflict. Jewish Israeli emigrants are known as yordim.[272]

Diaspora (outside Israel)

The waves of immigration to the United States and elsewhere at the turn of the 19th century, the founding of Zionism and later events, including pogroms in Imperial Russia (mostly within the Pale of Settlement in present-day Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus and eastern Poland), the massacre of European Jewry during the Holocaust, and the founding of the state of Israel, with the subsequent Jewish exodus from Arab lands, all resulted in substantial shifts in the population centers of world Jewry by the end of the 20th century.[275]

More than half of the Jews live in the Diaspora (see Population table). Currently, the largest Jewish community outside Israel, and either the largest or second-largest Jewish community in the world, is located in the United States, with 6 million to 7.5 million Jews by various estimates. Elsewhere in the Americas, there are also large Jewish populations in Canada (315,000), Argentina (180,000–300,000), and Brazil (196,000–600,000), and smaller populations in Mexico, Uruguay, Venezuela, Chile, Colombia and several other countries (see History of the Jews in Latin America).[276] According to a 2010 Pew Research Center study, about 470,000 people of Jewish heritage live in Latin America and the Caribbean.[258] Demographers disagree on whether the United States has a larger Jewish population than Israel, with many maintaining that Israel surpassed the United States in Jewish population during the 2000s, while others maintain that the United States still has the largest Jewish population in the world. Currently, a major national Jewish population survey is planned to ascertain whether or not Israel has overtaken the United States in Jewish population.[277]

Western Europe's largest Jewish community, and the third-largest Jewish community in the world, can be found in France, home to between 483,000 and 500,000 Jews, the majority of whom are immigrants or refugees from North African countries such as Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia (or their descendants).[278] The United Kingdom has a Jewish community of 292,000. In Eastern Europe, the exact figures are difficult to establish. The number of Jews in Russia varies widely according to whether a source uses census data (which requires a person to choose a single nationality among choices that include "Russian" and "Jewish") or eligibility for immigration to Israel (which requires that a person have one or more Jewish grandparents). According to the latter criteria, the heads of the Russian Jewish community assert that up to 1.5 million Russians are eligible for aliyah.[279][280] In Germany, the 102,000 Jews registered with the Jewish community are a slowly declining population,[281] despite the immigration of tens of thousands of Jews from the former Soviet Union since the fall of the Berlin Wall.[282] Thousands of Israelis also live in Germany, either permanently or temporarily, for economic reasons.[283]

Prior to 1948, approximately 800,000 Jews were living in lands which now make up the Arab world (excluding Israel). Of these, just under two-thirds lived in the French-controlled Maghreb region, 15 to 20 percent in the Kingdom of Iraq, approximately 10 percent in the Kingdom of Egypt and approximately 7 percent in the Kingdom of Yemen. A further 200,000 lived in Pahlavi Iran and the Republic of Turkey. Today, around 26,000 Jews live in Arab countries[284] and around 30,000 in Iran and Turkey. A small-scale exodus had begun in many countries in the early decades of the 20th century, although the only substantial aliyah came from Yemen and Syria.[285] The exodus from Arab and Muslim countries took place primarily from 1948. The first large-scale exoduses took place in the late 1940s and early 1950s, primarily in Iraq, Yemen and Libya, with up to 90 percent of these communities leaving within a few years. The peak of the exodus from Egypt occurred in 1956. The exodus in the Maghreb countries peaked in the 1960s. Lebanon was the only Arab country to see a temporary increase in its Jewish population during this period, due to an influx of refugees from other Arab countries, although by the mid-1970s the Jewish community of Lebanon had also dwindled. In the aftermath of the exodus wave from Arab states, an additional migration of Iranian Jews peaked in the 1980s when around 80 percent of Iranian Jews left the country.[citation needed]

Outside Europe, the Americas, the Middle East, and the rest of Asia, there are significant Jewish populations in Australia (112,500) and South Africa (70,000).[35] There is also a 6,800-strong community in New Zealand.[286]

Demographic changes

Assimilation

Since at least the time of the Ancient Greeks, a proportion of Jews have assimilated into the wider non-Jewish society around them, by either choice or force, ceasing to practice Judaism and losing their Jewish identity.[287] Assimilation took place in all areas, and during all time periods,[287] with some Jewish communities, for example the Kaifeng Jews of China, disappearing entirely.[288] The advent of the Jewish Enlightenment of the 18th century (see Haskalah) and the subsequent emancipation of the Jewish populations of Europe and America in the 19th century, accelerated the situation, encouraging Jews to increasingly participate in, and become part of, secular society. The result has been a growing trend of assimilation, as Jews marry non-Jewish spouses and stop participating in the Jewish community.[289]

Rates of interreligious marriage vary widely: In the United States, it is just under 50 percent,[290] in the United Kingdom, around 53 percent; in France; around 30 percent,[291] and in Australia and Mexico, as low as 10 percent.[292] In the United States, only about a third of children from intermarriages affiliate with Jewish religious practice.[293] The result is that most countries in the Diaspora have steady or slightly declining religiously Jewish populations as Jews continue to assimilate into the countries in which they live.[citation needed]

War and persecution

The Jewish people and Judaism have experienced various persecutions throughout Jewish history. During Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, the Roman Empire (in its later phases known as the Byzantine Empire) repeatedly repressed the Jewish population, first by ejecting them from their homelands during the pagan Roman era and later by officially establishing them as second-class citizens during the Christian Roman era.[294][295]

According to James Carroll, "Jews accounted for 10% of the total population of the Roman Empire. By that ratio, if other factors had not intervened, there would be 200 million Jews in the world today, instead of something like 13 million."[296]

Later in medieval Western Europe, further persecutions of Jews by Christians occurred, notably during the Crusades—when Jews all over Germany were massacred—and in a series of expulsions from the Kingdom of England, Germany, and France. Then there occurred the largest expulsion of all, when Spain and Portugal, after the Reconquista (the Catholic Reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula), expelled both unbaptized Sephardic Jews and the ruling Muslim Moors.[297][298]

In the Papal States, which existed until 1870, Jews were required to live only in specified neighborhoods called ghettos.[299]

Islam and Judaism have a complex relationship. Traditionally Jews and Christians living in Muslim lands, known as dhimmis, were allowed to practice their religions and administer their internal affairs, but they were subject to certain conditions.[300] They had to pay the jizya (a per capita tax imposed on free adult non-Muslim males) to the Islamic state.[300] Dhimmis had an inferior status under Islamic rule. They had several social and legal disabilities such as prohibitions against bearing arms or giving testimony in courts in cases involving Muslims.[301] Many of the disabilities were highly symbolic. The one described by Bernard Lewis as "most degrading"[302] was the requirement of distinctive clothing, not found in the Quran or hadith but invented in early medieval Baghdad; its enforcement was highly erratic.[302] On the other hand, Jews rarely faced martyrdom or exile, or forced compulsion to change their religion, and they were mostly free in their choice of residence and profession.[303]

Notable exceptions include the massacre of Jews and forcible conversion of some Jews by the rulers of the Almohad dynasty in Al-Andalus in the 12th century,[304] as well as in Islamic Persia,[305] and the forced confinement of Moroccan Jews to walled quarters known as mellahs beginning from the 15th century and especially in the early 19th century.[306] In modern times, it has become commonplace for standard antisemitic themes to be conflated with anti-Zionist publications and pronouncements of Islamic movements such as Hezbollah and Hamas, in the pronouncements of various agencies of the Islamic Republic of Iran, and even in the newspapers and other publications of Turkish Refah Partisi."[307][better source needed]

Throughout history, many rulers, empires and nations have oppressed their Jewish populations or sought to eliminate them entirely. Methods employed ranged from expulsion to outright genocide; within nations, often the threat of these extreme methods was sufficient to silence dissent. The history of antisemitism includes the First Crusade which resulted in the massacre of Jews;[297] the Spanish Inquisition (led by Tomás de Torquemada) and the Portuguese Inquisition, with their persecution and autos-da-fé against the New Christians and Marrano Jews;[308] the Bohdan Chmielnicki Cossack massacres in Ukraine;[309] the Pogroms backed by the Russian Tsars;[310] as well as expulsions from Spain, Portugal, England, France, Germany, and other countries in which the Jews had settled.[298] According to a 2008 study published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, 19.8 percent of the modern Iberian population has Sephardic Jewish ancestry,[311] indicating that the number of conversos may have been much higher than originally thought.[312][313]

The persecution reached a peak in Nazi Germany's Final Solution, which led to the Holocaust and the slaughter of approximately 6 million Jews.[314] Of the world's 16 million Jews in 1939, almost 40% were murdered in the Holocaust.[315] The Holocaust—the state-led systematic persecution and genocide of European Jews (and certain communities of North African Jews in European controlled North Africa) and other minority groups of Europe during World War II by Germany and its collaborators—remains the most notable modern-day persecution of Jews.[316] The persecution and genocide were accomplished in stages. Legislation to remove the Jews from civil society was enacted years before the outbreak of World War II.[317] Concentration camps were established in which inmates were used as slave labour until they died of exhaustion or disease.[318] Where the Third Reich conquered new territory in Eastern Europe, specialized units called Einsatzgruppen murdered Jews and political opponents in mass shootings.[319] Jews and Roma were crammed into ghettos before being transported hundreds of kilometres by freight train to extermination camps where, if they survived the journey, the majority of them were murdered in gas chambers.[320] Virtually every arm of Germany's bureaucracy was involved in the logistics of the mass murder, turning the country into what one Holocaust scholar has called "a genocidal nation."[321]

Migrations

Throughout Jewish history, Jews have repeatedly been directly or indirectly expelled from both their original homeland, the Land of Israel, and many of the areas in which they have settled. This experience as refugees has shaped Jewish identity and religious practice in many ways, and is thus a major element of Jewish history.[322] The patriarch Abraham is described as a migrant to the land of Canaan from Ur of the Chaldees[323] after an attempt on his life by King Nimrod.[324] His descendants, the Children of Israel, in the Biblical story (whose historicity is uncertain) undertook the Exodus (meaning "departure" or "exit" in Greek) from ancient Egypt, as recorded in the Book of Exodus.[325]

Centuries later, Assyrian policy was to deport and displace conquered peoples, and it is estimated some 4,500,000 among captive populations suffered this dislocation over three centuries of Assyrian rule.[326] With regard to Israel, Tiglath-Pileser III claims he deported 80% of the population of Lower Galilee, some 13,520 people.[327] Some 27,000 Israelites, 20 to 25% of the population of the Kingdom of Israel, were described as being deported by Sargon II, and were replaced by other deported populations and sent into permanent exile by Assyria, initially to the Upper Mesopotamian provinces of the Assyrian Empire.[328][329] Between 10,000 and 80,000 people from the Kingdom of Judah were similarly exiled by Babylonia,[326] but these people were then returned to Judea by Cyrus the Great of the Persian Achaemenid Empire.[330]

Many Jews were exiled again by the Roman Empire.[331] The 2,000 year dispersion of the Jewish diaspora beginning under the Roman Empire,[332] as Jews were spread throughout the Roman world and, driven from land to land,[333] settled wherever they could live freely enough to practice their religion. Over the course of the diaspora the center of Jewish life moved from Babylonia[334] to the Iberian Peninsula[335] to Poland[336] to the United States[337] and, as a result of Zionism, back to Israel.[338]

There were also many expulsions of Jews during the Middle Ages and Enlightenment in Europe, including: 1290, 16,000 Jews were expelled from England, see the (Statute of Jewry); in 1396, 100,000 from France; in 1421, thousands were expelled from Austria. Many of these Jews settled in East-Central Europe, especially Poland.[339] Following the Spanish Inquisition in 1492, the Spanish population of around 200,000 Sephardic Jews were expelled by the Spanish crown and Catholic church, followed by expulsions in 1493 in Sicily (37,000 Jews) and Portugal in 1496. The expelled Jews fled mainly to the Ottoman Empire, the Netherlands, and North Africa, others migrating to Southern Europe and the Middle East.[340]

During the 19th century, France's policies of equal citizenship regardless of religion led to the immigration of Jews (especially from Eastern and Central Europe).[341] This contributed to the arrival of millions of Jews in the New World. Over two million Eastern European Jews arrived in the United States from 1880 to 1925.[342]

In summary, the pogroms in Eastern Europe,[310] the rise of modern antisemitism,[343] the Holocaust,[344] as well as the rise of Arab nationalism,[345] all served to fuel the movements and migrations of huge segments of Jewry from land to land and continent to continent until they arrived back in large numbers at their original historical homeland in Israel.[338]

In the latest phase of migrations, the Islamic Revolution of Iran caused many Iranian Jews to flee Iran. Most found refuge in the US (particularly Los Angeles, California, and Long Island, New York) and Israel. Smaller communities of Persian Jews exist in Canada and Western Europe.[346] Similarly, when the Soviet Union collapsed, many of the Jews in the affected territory (who had been refuseniks) were suddenly allowed to leave. This produced a wave of migration to Israel in the early 1990s.[272]

Growth

Israel is the only country with a Jewish population that is consistently growing through natural population growth, although the Jewish populations of other countries, in Europe and North America, have recently increased through immigration. In the Diaspora, in almost every country the Jewish population in general is either declining or steady, but Orthodox and Haredi Jewish communities, whose members often shun birth control for religious reasons, have experienced rapid population growth.[347]

Orthodox and Conservative Judaism discourage proselytism to non-Jews, but many Jewish groups have tried to reach out to the assimilated Jewish communities of the Diaspora in order for them to reconnect to their Jewish roots. Additionally, while in principle Reform Judaism favours seeking new members for the faith, this position has not translated into active proselytism, instead taking the form of an effort to reach out to non-Jewish spouses of intermarried couples.[348]

There is also a trend of Orthodox movements reaching out to secular Jews in order to give them a stronger Jewish identity so there is less chance of intermarriage. As a result of the efforts by these and other Jewish groups over the past 25 years, there has been a trend (known as the Baal teshuva movement) for secular Jews to become more religiously observant, though the demographic implications of the trend are unknown.[349] Additionally, there is also a growing rate of conversion to Jews by Choice of gentiles who make the decision to head in the direction of becoming Jews.[350]

Contributions

Jewish individuals have played a significant role in the development and growth of Western culture,[50][51] advancing many fields of thought, science and technology,[40] both historically and in modern times,[351] including through discrete trends in Jewish philosophy, Jewish ethics[352] and Jewish literature,[40] as well as specific trends in Jewish culture, including in Jewish art, Jewish music, Jewish humor, Jewish theatre, Jewish cuisine and Jewish medicine.[44][45] Jews have established various Jewish political movements,[40] religious movements, and, through the authorship of the Hebrew Bible and parts of the New Testament,[46][47] provided the foundation for Christianity and Islam.[48][49] More than 20 percent[353][354][355][356][357][358] of the awarded Nobel Prize have gone to individuals of Jewish descent.[359]

Notes

- ^ The global core Jewish population was estimated at approximately 15,263,500 in 2022. When including individuals who identify as partly Jewish and anyone with one or two Jewish parents increases the estimate to 20,028,800. Adding individuals with a Jewish background but without Jewish parents, and non-Jewish household members living with Jews, yields an enlarged estimate of 22,720,400.[1]

- ^ The exact world Jewish population, however, is difficult to measure. In addition to issues with census methodology, disputes among proponents of halakhic, secular, political, and ancestral identification factors regarding who is a Jew may affect the figure considerably depending on the source.[39]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p American Jewish Year Book 2022. Vol. 122. 2023. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-33406-1. ISBN 978-3-031-33405-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Dashefsky, Arnold; Della-Pergola, Sergio; Sheskin, Ira, eds. (2021). World Jewish Population (PDF) (Report). Berman Jewish DataBank. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d https://www.timesofisrael.com/worlds-jewish-population-hits-15-8-million-on-eve-of-rosh-hashanah/

- ^ a b c d e f "Global Jewish population hits 15.7 million ahead of new year, 46% of them in Israel". The Times of Israel.

- ^ a b c "Links". Beth Hatefutsoth. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ "New Poll Shows Atheism on Rise, With Jews Found to Be Least Religious". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ Kiaris, Hippokratis (2012). Genes, Polymorphisms and the Making of Societies: How Genetic Behavioral Traits Influence Human Cultures. Universal Publishers. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-61233-093-8.

- ^ a b Shen, Peidong; Lavi, Tal; Kivisild, Toomas; Chou, Vivian; Sengun, Deniz; Gefel, Dov; Shpirer, Issac; Woolf, Eilon; Hillel, Jossi; Feldman, Marcus W.; Oefner, Peter J. (September 2004). "Reconstruction of patrilineages and matrilineages of Samaritans and other Israeli populations from Y-Chromosome and mitochondrial DNA sequence Variation". Human Mutation. 24 (3): 248–260. doi:10.1002/humu.20077. ISSN 1059-7794. PMID 15300852. S2CID 1571356.

- ^ Ridolfo, Jim (2015). Digital Samaritans: Rhetorical Delivery and Engagement in the Digital Humanities. University of Michigan Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-472-07280-4.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (9 June 2010). "Studies Show Jews' Genetic Similarity". The New York Times.

- ^ Nebel, Almut; Filon, Dvora; Weiss, Deborah A.; Weale, Michael; Faerman, Marina; Oppenheim, Ariella; Thomas, Mark G. (December 2000). "High-resolution Y chromosome haplotypes of Israeli and Palestinian Arabs reveal geographic substructure and substantial overlap with haplotypes of Jews". Human Genetics. 107 (6): 630–641. doi:10.1007/s004390000426. PMID 11153918. S2CID 8136092.

- ^ "Jews Are the Genetic Brothers of Palestinians, Syrians, and Lebanese". Sciencedaily.com. 9 May 2000. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ a b Atzmon, Gil; Hao, Li; Pe'er, Itsik; Velez, Christopher; Pearlman, Alexander; Palamara, Pier Francesco; Morrow, Bernice; Friedman, Eitan; Oddoux, Carole; Burns, Edward; Ostrer, Harry (June 2010). "Abraham's Children in the Genome Era: Major Jewish Diaspora Populations Comprise Distinct Genetic Clusters with Shared Middle Eastern Ancestry". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 86 (6): 850–859. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.015. PMC 3032072. PMID 20560205.

- ^ a b

- Ethnic minorities in English law. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved on 23 December 2010.

- Edgar Litt (1961). "Jewish Ethno-Religious Involvement and Political Liberalism". Social Forces. 39 (4): 328–32. doi:10.2307/2573430. JSTOR 2573430.

- Craig R. Prentiss (2003). Religion and the Creation of Race and Ethnicity: An Introduction. NYU Press. pp. 85–. ISBN 978-0-8147-6700-9.

- The Avraham Harman Institute of Contemporary Jewry The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Eli Lederhendler Stephen S. Wise Professor of American Jewish History and Institutions (2001). Studies in Contemporary Jewry : Volume XVII: Who Owns Judaism? Public Religion and Private Faith in America and Israel: Volume XVII: Who Owns Judaism? Public Religion and Private Faith in America and Israel. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-0-19-534896-5.

- Ernest Krausz; Gitta Tulea. Jewish Survival: The Identity Problem at the Close of the Twentieth Century; [... International Workshop at Bar-Ilan University on the 18th and 19th of March, 1997]. Transaction Publishers. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-1-4128-2689-1.

- John A. Shoup III (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-59884-363-7.

- Tet-Lim N. Yee (2005). Jews, Gentiles and Ethnic Reconciliation: Paul's Jewish identity and Ephesians. Cambridge University Press. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-1-139-44411-8.

- ^ *M. Nicholson (2002). International Relations: A Concise Introduction. NYU Press. pp. 19–. ISBN 978-0-8147-5822-9.

The Jews are a nation and were so before there was a Jewish state of Israel

- Jacob Neusner (1991). An Introduction to Judaism: A Textbook and Reader. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 375–. ISBN 978-0-664-25348-6.

That there is a Jewish nation can hardly be denied after the creation of the State of Israel

- Alan Dowty (1998). The Jewish State: A Century Later, Updated With a New Preface. University of California Press. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-0-520-92706-3.

Jews are a people, a nation (in the original sense of the word), an ethnos

- Brandeis, Louis (25 April 1915). "The Jewish Problem: How To Solve It". University of Louisville School of Law. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

Jews are a distinctive nationality of which every Jew, whatever his country, his station or shade of belief, is necessarily a member

- Palmer, Edward Henry (2002) [First published 1874]. A History of the Jewish Nation: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-931956-69-7. OCLC 51578088. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- Jacob Neusner (1991). An Introduction to Judaism: A Textbook and Reader. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 375–. ISBN 978-0-664-25348-6.

- ^ *Facts On File, Incorporated (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. Infobase Publishing. pp. 337–. ISBN 978-1-4381-2676-0.